Abstract

The adenosine A2B receptor (A2BR) has a wide tissue distribution that includes fibroblasts and endothelial and epithelial cells. The recent generation of an A2BR−/− mouse constructed with a β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene under control of the endogenous promoter has provided a valuable tool to quantify A2BR promoter activity (29). To determine the sites of expression of the A2B receptor in the mouse lung, histological and flow cytometric analysis of β-gal reporter gene expression in various lung cell populations was performed. The major site of A2BR promoter activity was found to be the type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), identified by coexpression of prosurfactant protein C, with relatively less expression in alveolar macrophages, bronchial epithelial cells, and cells of the vasculature. Highly purified type II AECs were prepared by fluorescence-activated sorting of enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-positive cells from transgenic mice expressing eGFP under control of the surfactant protein C promoter (21). The type II cells expressed 89-fold higher A2BR mRNA than pulmonary leukocytes, and the A2BR was shown to be functional, as treatment of purified type II AECs with the nonspecific adenosine receptor agonist 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) induced an increase in intracellular cAMP greater that the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol that was inhibited completely following treatment by ATL-802, a novel, highly potent (Ki = 8.6 nM), and selective (>900 fold over other adenosine receptor subtypes) antagonist of the mouse A2BR.

Keywords: lung, β-galactosidase, G protein-coupled receptor, cAMP

the adenosine a2b receptor (A2BR) is one of four subtypes of G protein-coupled adenosine receptors: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. A2A and A2B signal through Gs, whereas A1 and A3 signal through Gi. The A2BR has been reported to also signal through Gq in certain cell types and environments (9, 23). Until recently, characterization of the A2BR has been challenging due to the lack of specific pharmacological tools and the absence of an A2BR knockout mouse. Compared with the other adenosine receptors, the A2BR has relatively low affinity for adenosine and the commonly used nonselective adenosine analog 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) (Ki >100 nM) (8). In comparison, NECA binds to other adenosine receptor subtypes with Ki values in the low nanomolar range. In this study, we have taken advantage of a new selective antagonist of the mouse A2B receptor, ATL-802, and the A2BR−/− mouse with a β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene under control of the endogenous promoter (29) to explore the location and physiological function of the A2BR in murine lung.

The lung epithelium at the level of the alveolus comprises two distinct cell types, type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECs). Together with alveolar macrophages, these cells provide a barrier to the environment that protects the lung from toxins, infections, oxidative damage, and other insults. Type II AECs are small cells that comprise only 5% of the total alveolar surface area but account for 15% of total cells in the distal lung (24). In addition to their barrier function, other activities of type II AECs include surfactant production and metabolism, ion transport and fluid regulation, alveolar repair in response to injury, and newly recognized roles in innate immunity (7, 17).

In this study, we describe high density A2BR expression on type II AECs in the mouse lung that has previously been unrecognized, and we demonstrate that these receptors are functional on highly purified sorted cells expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under control of the promoter for the type II AEC marker, surfactant protein C (SP-C-eGFP) (21). The identification of high density, functional A2BR expression on type II AECs suggests that adenosine may play an important role in regulating type II AEC function during periods of high pulmonary adenosine production, such as injury or infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia. Mice were 8–12 wk of age. C57BL/6 animals were purchased from Jackson Labs. A2BR−/− congenic to C57BL/6 were a gift of Dr. K. Ravid (Boston, MA). Heterozygotes (A2BR+/−) were prepared by breeding A2BR−/− mice with wild-type C57BL/6. SP-C-eGFP mice were the gift of Dr. M. O'Reilly (Rochester, NY) and are congenic to C57BL/6.

Inflation fixation.

Mice were euthanized using an overdose of pentobarbital sodium. The pulmonary vasculature was perfused free of blood, and the trachea was cannulated. The lungs were inflation-fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 25 cmH2O. The lungs were then excised en bloc and immersed in 5 ml 4% paraformaldehyde for an additional 15 min. They were then rinsed in PBS for 25 min.

β-gal staining.

Fixed tissues were immersed in 5 ml of X-gal staining buffer (5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml X-gal, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% deoxycholate in PBS). Tissues were rocked at room temperature overnight while protected from light, rinsed in PBS, immersed in 70% ethanol, and processed for paraffin embedding. Embedded tissues were sectioned and counterstained using hematoxylin or subjected to immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry.

Five-micrometer paraffin sections were rehydrated, quenched with aqueous hydrogen peroxide (0.45%) for 15 min, and washed with deionized H2O followed by PBS with 0.5% fish skin gelatin (PBS/FSG), 10% normal rabbit or donkey serum, and Vector avidin block for 60 min. Primary rat anti-Mac-2 antibody (Cedarlane) diluted 1:10,000 or primary anti-prosurfactant protein C (Chemicon) diluted 1:1,500 was applied overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed in PBS/FSG 4 × 5 min. Biotinylated rabbit anti-rat (Vector) or donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch) secondary antibody was applied for 60 min at room temperature. After washing 4 × 5 min in PBS, the sections were incubated in Vector ABC Elite solution for 30 min. DAB substrate (Dako) was used (5 min) to visualize staining. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin I.

Cell dissociation.

The method for cell dissociation and alveolar type II cell enrichment was adapted from Corti et al. (4). Briefly, mice were anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium, and the lungs were perfused free of blood with PBS. The trachea was cannulated, and 3 ml of dispase (BD Biosciences) was instilled followed immediately by 1 ml of 1% low-melt agarose. Ice-cold saline-soaked gauze was placed over the exposed lung for 2 min. Lungs were removed en bloc and immersed in 2 ml of dispase and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Lung tissue was separated from bronchial structures and rocked gently in DMEM + 10 mM HEPES + 10%FBS (Gibco) for 5 min. Tissue was then subject to serial filtration through 100- and 40-μm cell strainers (BD Biosciences) followed by 20-μm nylon gauze (Nytex). Single cell suspensions were centrifuged at 300 g for 8 min, resuspended in DMEM + 10 mM HEPES + 10%FBS, and incubated on α-CD45- and α-CD16/32- (clones 30-F11, 93, eBioscience) coated plates for 2 h. Nonadhered cells were gently removed and used for subsequent studies. For RT-PCR studies in which a population of leukocytes was desired, the subtraction step on antibody-coated plates was omitted.

Fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside staining.

Fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside (FDG; Sigma-Aldrich) is a substrate for β-gal that can be used to identify β-gal-positive cells by flow cytometry. Cells were centrifuged at 300 g for 8 min, and the red blood cells were lysed (RBC lysis buffer, Sigma-Aldrich). Remaining cells were resuspended in staining buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 300 μM chloroquine) and warmed to 37°C. Cells were loaded with FDG by hypotonic loading. An equal volume of prewarmed 2 mM FDG in H2O was added to the cell suspension and allowed to incubate for 1 min before quenching with 10 vol of ice-cold staining buffer. Cells were centrifuged at 300 g for 8 min at 4°C and resuspended in ice-cold staining buffer. Stained cells were held on ice until ready for FACS analysis.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Live cells were sorted based on fluorescein or eGFP fluorescence, and viability was assessed using 2 μg/ml propidium iodide (Invitrogen). Sorted cells used for RT-PCR experiments were also labeled with APC α-CD45 (clone 30-F11, eBioscience). Fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSVantage SE Turbo Sorter with DIVA Option. Some populations of sorted cells were applied to a slide using a Cytospin (Thermo-Shandon) at a concentration of 25,000–50,000 cells/slide for immunohistochemistry, whereas others were used for subsequent assays.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Sorted populations of cells were resuspended in 1 ml of TRI-Reagent (Ambion), and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was obtained using the Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). RT-PCR was performed using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad iCycler IQ thermal cycler. Primers for the A2BR were forward 5′-gcttcgtgctggtgctcaca-3′ and reverse 5′-cctctcgctcgtgtcccagt-3′; primers for the A1R were forward 5′-cctgagtgaggtggaacaag-3′ and reverse 5′-accagaggaggctgacac-3′; primers for the A2AR were forward 5′-tggcttggtgacgggtatg-3′ and reverse 5′-cgcaggtctttgtggagttc-3′; and primers for the A3R were forward 5′-gagacggactggctgaacatc-3′ and reverse 5′-tcttgacttgcaggctgacag-3′. Primers for the GAPDH housekeeping gene were forward 5′-ttcaccaccatggagaaggc-3′ and reverse 5′-ggcatggactgtggtcatga-3′. Data analysis and fold-change estimation were performed using the ΔΔCt method.

Radioligand binding assays.

The methods used for radioligand binding studies have been described previously (25). In brief, all four subtypes of recombinant human and murine adenosine receptors were stably expressed in HEK-293 cells or CHO-K1 cells. Crude membrane preparations from transfected cells were diluted in HE buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) at concentrations between 2 and 50 μg/tube in a volume of 150 μl, and adenosine deaminase was added at 2 U/ml. Dilutions of antagonist compounds were prepared at 10× final concentrations in HE containing 10% DMSO. Radioligands were as follows: 125I-N6-aminobenzyladenosine (125I-ABA) for A1 and A3 receptors and 125I-4-(2-[7-Amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin- 5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol (125I-ZM241385) for A2A receptors. [3H]-6-fluoro-N-(5-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-di(2,3-ditritiumpropyl)-1H-purin-8-yl)pyridin-2-yl)-N-(2-methoxyethyl)pyridine-3-carboxamide ([3H]ATL-852) was characterized as an improved radioligand for A2B receptors. Diluted antagonists (25 μl) were added to each membrane sample (150 μl). The radioligand was added in a 75-μl volume, the tubes were incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature, filtered through glass fiber filters, and counted in either a Wallac 1470 Wizard Automatic Gamma Counter (125I) or a Beckman LS6500 Multipurpose Scintillation Counter (3H). Samples were assayed in triplicate. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of NECA (100 μM).

cAMP assay.

Sorted cells were plated in serum-free SAGM (Lonza) + 1 U/ml adenosine deaminase (Roche) at a density of 50,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and were allowed to recover for 2 h before stimulation. In some instances, ATL-802 (100 nM) was added for 20 min before agonist stimulation. NECA (10 μM) or the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (10 μM) was used to stimulate cells, and all wells received 10 μM rolipram to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity simultaneous with agonist. Stimulation was allowed to proceed for 15 min, and cAMP accumulation was measured by cAMP-Screen Immunoassay System (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

The A2BR promoter is highly active in type II AEC in murine lung.

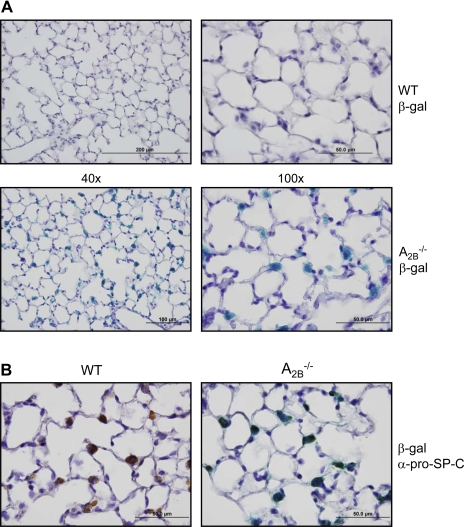

The location of A2B receptor promoter activity in mouse lung was evaluated by immunohistochemistry and reporter gene expression. The A2BR−/− reporter gene knockin mouse model contains the prokaryotic reporter gene β-gal, under control of the endogenous A2BR promoter (29). Staining of naïve A2BR−/− mouse lungs for β-gal revealed the highest expression in cuboidal, junctional cells of the alveolus with no background staining evident in C57BL/6 (WT) mice (Fig. 1A). Prosurfactant protein C (pro-SP-C), an unprocessed form of surfactant protein C, is a specific marker for type II AEC, as these are the only cell types that expresses this protein. Immunohistochemistry of lung sections dually stained for β-gal expression and with anti-pro-SP-C antibody revealed colocalization of these markers, indicating type II AEC are the principal sites of A2BR promoter activity in the mouse lung (Fig. 1B). To determine whether similar staining patterns were observed in animals with functional A2B receptors, A2B+/− animals were bred for similar studies. Results of β-gal and pro-SP-C staining colocalization in tissue sections from A2B+/− animals were similar to those from A2BKO animals, although the intensity of β-gal staining was decreased, as expected, from gene dilution (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Reporter gene expression for the adenosine A2B receptor is highly localized to type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) in murine lung. A: ×40 (left) and ×100 (right) images of sections from lungs of naïve C57BL/6J (WT) and A2BR−/− animals stained for expression of the β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene under the control of the endogenous adenosine A2B receptor (A2BR) promoter in A2BR−/− mice. B: immunostaining of wild-type (left) and A2BKO (right) lung sections for pro-SP-C expression following staining for β-gal. Positive staining for pro-SP-C colocalizes with β-galactosidase expression.

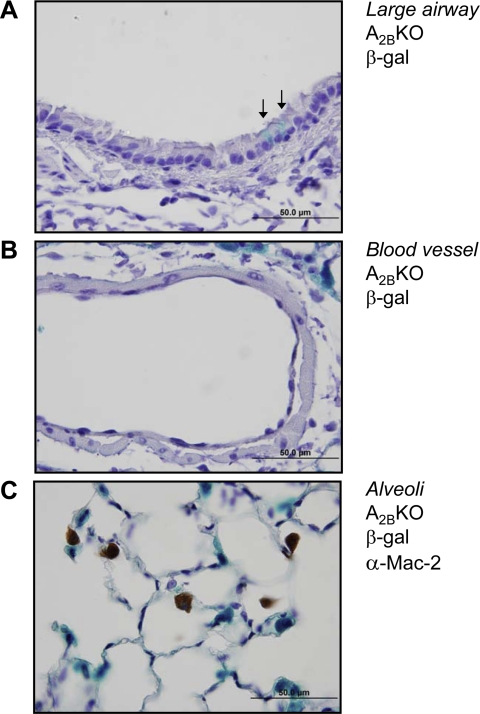

A2BR promoter activity in type II AECs exceeds activity in alveolar macrophages, bronchial epithelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle.

Other sites of A2BR expression were explored, including large airway epithelial cells, vascular cells, and alveolar macrophages. Large airway epithelial cells had an irregular β-gal staining pattern, with individual cells showing β-gal expression but with the majority of epithelial cells showing no detectable staining (Fig. 2A). Additionally, β-gal staining was below detectable limits in vascular endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle in lung sections (Fig. 2B). Costaining of lung sections for β-gal activity and with an antibody against Mac-2, a marker for macrophages, including alveolar macrophages, showed no significant colocalization of staining (Fig. 2C). Although functional A2BRs and A2BR mRNA can be detected in epithelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle, these data suggest that A2BR promoter activity in large airway epithelial cells, alveolar macrophages, and vascular cells is far less than in type II AECs.

Fig. 2.

Reporter gene expression for the A2BR is rare on large airway epithelial cells and undetectable in cells of the vasculature and alveolar macrophages. Lungs of A2BR−/− mice were stained for β-gal expression, and the epithelial cells of the large airways (A) and cells of the vasculature (B) were examined. In large airway epithelial cells, β-gal staining was occasionally observed in individual cells (arrows) or patches of cells, but was not seen in the majority of cells. In all vessels examined, no β-gal staining was observed in the endothelium or vascular smooth muscle. Some staining of peripheral type II AECs is visible in the top right corner of B. C: immunostaining of A2BR−/− lung sections for Mac-2 expression following staining for β-gal. These stains did not colocalize, indicating macrophages, including alveolar macrophages, are not the principal site of A2BR reporter gene expression in the lung.

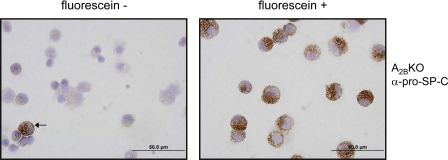

Sorted β-gal-positive cells stain positive for prosurfactant protein C.

To confirm that type II AEC are the primary site of expression of the A2BR in mouse lung, A2BR−/− mice were digested, loaded with fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside (a substrate that fluoresces only when cleaved by the β-gal enzyme to yield fluorescein), and subjected to FACS. Cells were separated and collected based on their fluorescein signal and subsequently stained for prosurfactant protein C expression. Usually, cells that were positive for fluorescein also stained positive for prosurfactant protein C (Fig. 3). In triplicate experiments, 5.4 ± 1.3% of fluorescein-negative and 98 ± 2% of fluorescein-positive cells stained positive for prosurfactant C (P < 0.0001). However, rare fluorescein-negative cells also stained positive for prosurfactant protein C (Fig. 3). Similar results were seen with sorted cells from A2BR+/− mice (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Cells sorted for A2BR reporter gene expression stain positive for pro-SP-C. Lungs of A2BKO animals were digested into single cell suspensions. Cells were stained using fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside, a nonfluorescent substrate for the enzyme β-gal that yields the fluorescent product fluorescein when cleaved. Single cells were sorted using FACS based on fluorescein expression and subsequently applied to a slide by Cytospin. Immunostaining for pro-SP-C revealed only rare pro-SP-C-positive cells in the sorted fluorescein-negative population (left, arrow), whereas all cells that were positive for fluorescein (right) also almost always stained positive for pro-SP-C.

Type II AECs express high levels of A2BR transcript.

It is not possible to obtain pure type II AECs from wild-type mouse lung. To prepare a nearly pure population of type II AECs that express a normal complement of A2BRs, we used a transgenic mouse model with eGFP under the control of the human surfactant protein C promoter (21). Using this model, a nearly pure population of type II AECs can be obtained by cell sorting. Two populations of cells were collected based on eGFP and CD45 expression. As expected, no cells were double positive for eGFP and the leukocyte marker, CD45. Sorted populations were subject to RT-PCR to quantify A2BR mRNA expression, and relative levels of expression (ΔΔCt) in eGFP-positive type II AECs were compared with the population of CD45-positive leukocytes. Type II AEC cells that were eGFP-positive had high relative expression of A2BR mRNA, expressing 89 ± 6.2-fold higher levels than CD45-positive leukocytes (P < 0.05). In addition, relative levels of the A1, A2A, and A3 adenosine receptor transcripts in type II AECs were assessed using RT-PCR and compared with A2BR transcript expression. In eGFP-positive type II AECs, the level of A2BR transcript was 3.5 ± 0.24-fold higher than A1R transcript, 34 ± 6.5-fold higher than A2AR transcript, and 79 ± 2.7-fold higher than A3R transcript, indicating that at the level of mRNA, the A2BR is the most abundant adenosine receptor transcript expressed in type II AECs.

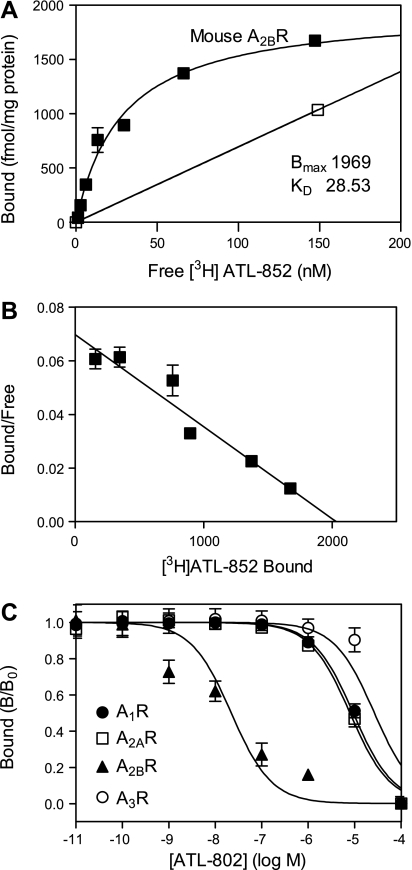

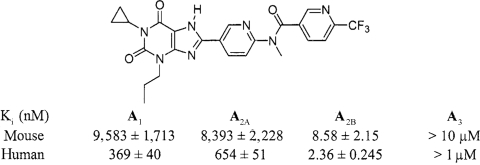

ATL-802 is a selective antagonist of the mouse A2BR.

Several potent and selective A2BR antagonists have been described in recent years. In general, xanthine compounds such as MRS1754 bind with lower potency and selectively to rodent than human A2B receptors (14). For this reason, we have searched for new radioligands and antagonists of mouse A2B receptors. A new radioligand, [3H]ATL-852, was found to bind to membranes derived from HEK-293 cells stably transfected with the recombinant mouse A2BR with a Bmax = 1,970 fmol/mg protein and a Kd = 28.5 nM (Fig. 4, A and B). In a screen of novel antagonists, ATL-802 was identified as a new potent A2BR-selective antagonist in competition binding assays to recombinant mouse A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors. As shown in Fig. 4C and Table 1, ATL-802 is more selective for mouse than human A2BRs. The Ki value for ATL-802 at the mouse A2BR was 8.6 ± 2.2 nM, and the antagonist exhibited excellent selectivity, 978-fold over the A2AR and greater than 1,000-fold over the A1 and A3 receptors.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of ATL-802 binding to the recombinant mouse A2BR. A: equilibrium binding of [3H]ATL-852 to membranes derived from HEK-293 cells stably transfected with the mouse A2BR. Specific (▪) and nonspecific equilibrium binding (□) was determined as described in materials and methods. The Bmax value is 1,969 fmol/mg protein; the Kd value is 28.53 nM. B: Scatchard transformation of specific binding. Each point is the mean ± SE of triplicate determinations. C: competition binding of ATL-802 to recombinant mouse adenosine receptors. Ki values were calculated and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Affinity of ATL-802 for recombinant adenosine receptors

Ki values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 3). Values were determined from competition radioligand binding experiments as described in materials and methods.

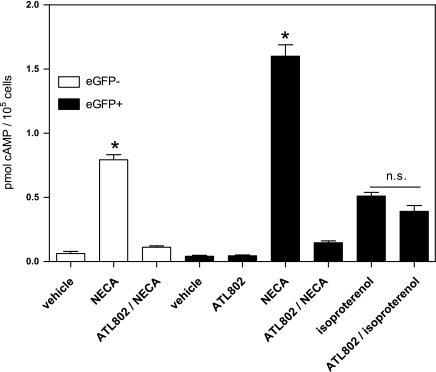

The A2BR on type II AECs is functional and stimulates cAMP formation.

To assess whether the A2B receptor on type II AECs is functional, dispersed cells from the lungs of SP-C-eGFP transgenic mice were sorted based on eGFP expression. Sorted cells were allowed to recover and subsequently stimulated with 10 μM NECA. Some cells were treated with 100 nM ATL-802, and cAMP formation was assessed following NECA-induced stimulation as evidence of A2BR activation. The β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (10 μM) was used as a positive control for Gs-stimulated cAMP accumulation. As shown in Fig. 5, eGFP-positive cells from SP-C-eGFP mice had increased cAMP formation in response to stimulation with NECA, and this response was inhibited almost completely by treatment with the selective A2BR antagonist, ATL-802. These eGFP-positive cells also increased cAMP accumulation in response to stimulation with isoproterenol, but the magnitude was 3.1 times less than that seen with NECA stimulation. ATL-802 did not significantly block isoproterenol-induced cAMP accumulation. In the eGFP-negative population, stimulation with NECA also increased cAMP, and this response was also inhibited by ATL-802; however, the magnitude of response to NECA was significantly lower than in eGFP-positive cells.

Fig. 5.

Activation of the A2BR elevates cAMP in a purified population of type II AECs. Single cell suspensions of lung from SP-C-eGFP mice were sorted based on eGFP expression and viability. Cells were allowed to recover overnight and were then stimulated with 10 μM NECA ± 100 nM ATL-802 or 10 μM isoproterenol ± 100 nM ATL-802. cAMP accumulation following stimulation was measured by immunoassay. Purified type II AECs (eGFP+) from SP-C-eGFP mice showed increased cAMP accumulation following NECA stimulation. This increase in cAMP was due to specific activation of the A2BR, as treatment with the antagonist ATL-802 inhibited this effect almost completely. Treatment with isoproterenol induced cAMP accumulation, but was unaffected by pretreatment with ATL-802. The assay was performed in triplicate and is representative of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 relative to all other groups; n.s., not significant, based on one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show evidence that the highest expression of A2BRs in the lung is on type II airway epithelial cells. These receptors are functional, and when maximally activated, generate over 3 times more cAMP than maximally activated β-adrenergic receptors. We took advantage of the reporter gene construct in the A2BR−/− mouse model that permits use of β-gal expression as a marker for endogenous A2BR promoter activity. The same approach was used to identify A2BR promoter activity in the vasculature of several tissues (29). It can be argued that the A2BR−/− mouse may have adapted to the loss of endogenous receptor. In that case, reporter gene expression might not be representative of A2BR expression in a wild-type mouse. For this reason, we also examined A2B heterozygotes (A2BR+/−). The advantage of heterozygotes is that they possess one copy of the β-gal reporter gene as well as one copy of the functional A2BR gene. Hence, reporter gene expression in the setting of a mouse model with functional receptor expression can be determined. In all cases, reporter gene expression showed identical localization in A2BR−/− and A2BR+/− animals despite a decrease in intensity of β-gal staining in A2B+/− mice compared with A2BR−/− mice. We also used the transgenic SP-C-eGFP mouse in which eGFP is under control of the human surfactant protein C promoter. This model is useful because it provides a method to isolate pure type II AECs and study A2BR expression and function in these cells that have unaltered adenosine receptors (22).

Initially, we identified the major source of A2BR promoter activity in the lung based on β-gal reporter gene expression on cells that appeared to have morphological characteristics of type II AECs. This conclusion was confirmed based on colocalization of β-gal reporter gene expression and immunostaining for the type II AEC marker, pro-SP-C, on fixed lung sections from naïve animals. This finding was further confirmed by isolating pure populations of dissociated, β-gal-positive cells from A2BR−/− and A2BR+/− animals followed by immunostaining for pro-SP-C. While staining in fixed tissue showed colocalization of β-gal and pro-SP-C staining in nearly every type II AEC examined, results from dissociated cell populations showed that while every β-gal-positive cell is also pro-SP-C positive, there is a small population of β-gal-negative cells that stain positively for pro-SP-C. This might be due to a limitation of the staining technique, as fluorescein can leak out of cells rapidly. Stained cells were held on ice to minimize this effect, but it is possible that the β-gal-negative/pro-SP-C-positive population is an artifact and that these cells do actually express the β-gal reporter. Alternatively, it is possible that not every type II AEC expresses the A2B receptor at all times. Although this study supports the conclusion that most lung cells with high A2BR promoter activity are type II AECs (with the possible exception of a small fraction of large airway epithelial cells, Fig. 2), the converse might not necessarily be true, i.e., it is possible that not all type II AECs are positive for A2BR promoter activity at all times.

The A2BR has previously been documented to be expressed on multiple cell types in the mouse lung, and perhaps the greatest significance of this study is identifying the type II AEC as expressing higher levels of the A2BR than these other cell populations. Before this study, the principal site of expression for the A2BR has been thought to be bronchial epithelial cells of medium and large airways (2, 3, 19, 33). Functional A2B expression has also been demonstrated in alveolar macrophages, fibroblasts, and bronchial smooth muscle (2, 31, 32). In the initial characterization of the A2BR−/− mouse, β-gal reporter characterization was not shown in the lung, but the authors concluded that the principal site of A2B expression was the vasculature and macrophages, and it was stated that reporter activity was observed in the lung vasculature (29). Interestingly, in the current study, we saw no detectable reporter staining in alveolar macrophages or pulmonary vasculature.

It is notable that in the SP-C-eGFP mouse, only 8–10% of type II AECs express eGFP (30). For this reason, eGFP-positive cells can be used to prepare highly enriched type II AECs, but eGFP-negative cells cannot be used as a source of cells lacking type II AECs. Based on RT-PCR characterization of A2BR mRNA expression in a purified type II AEC population and a purified mixed leukocyte population from the SP-C-eGFP mouse, the A2BR was the most abundantly expressed adenosine receptor subtype in type II AECs, and eGFP-positive type II AECs expressed ∼89-fold higher levels of A2BR mRNA than purified leukocytes (primarily consisting of alveolar macrophages).

The A2B receptor on the type II AEC is functional since activation of this receptor induced a rise in cAMP. The A2BR classically signals through Gs, and this is true in type II AECs as well. We were able to show that the NECA-induced rise in cAMP in type II AECs from the SP-C-eGFP transgenic mouse was due to activation of the A2BR and not the other adenosine receptor subtypes. We characterized a novel, selective antagonist of the mouse A2BR, ATL-802. The sorted, eGFP-positive type II AECs also showed an isoproterenol-induced rise in cAMP that was insensitive to inhibition with ATL-802. It has been well documented that β-adrenergic activation induces cAMP accumulation and subsequent surfactant release in type II AECs (11, 18, 20), yet activation of the A2BR in isolated type II AECs stimulated a 3.1-fold greater response in cAMP accumulation compared with β-adrenergic activation by a maximal concentration of isoproterenol, indicating a potentially greater role for the A2BR in regulation of type II AEC function. The eGFP-negative population also showed a NECA-induced rise in cAMP that could be inhibited by ATL-802, but the magnitude of the NECA response was significantly lower than in the eGFP-positive cells. As previously mentioned, only ∼10% of total type II AECs are positive for eGFP, and the smaller NECA response in eGFP-negative cells could be due in large part to type II AECs within that population. We can conclude that type II AECs have a functional A2B receptor and that A2B receptor activity is highest in this group of cells compared with other sorted populations.

Localization of A2BR expression to type II AECs is potentially functionally significant based on the known roles of both A2BR signaling and type II AEC biology. A2BR activity has long been theorized to control chloride and water secretion in pulmonary epithelial cells (12, 15). This was classically thought to be a function of larger airways, but the current study suggests an important role of type II AECs in controlling this effect. It was recently shown that the A2BR on a non-hematopoietic cell in the lung is responsible for alveolar fluid clearance following ventilator-induced lung injury (6). Based on the findings of the current study, we would predict that type II AEC cells are the primary regulators of fluid clearance, but further characterization of the type II cell in this model is necessary.

Type II cells are also known to regulate a variety of other functions, including surfactant production and secretion. It has been suggested that activation of the A2BR on the type II AEC induces surfactant release, but further pharmacological characterization is needed to completely understand this effect (10, 20). An interesting overlap of type II AEC and A2BR biology is in regulating immune responses. Type II AECs are known to actively participate in host defense by responding to pathogens through Toll-like receptors and actively secreting immune-modulating cytokines and chemokines (1, 13, 16, 26, 27). A2BR activation has been shown to have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, including controlling cytokine release and regulating vascular leak in response to injury (5, 28, 29, 32, 33). Further characterization of the A2BR on type II AEC is likely to reveal important downstream effects of this receptor, including modulation of the immune response to injury that may have broad implications in lung pathophysiology and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-073361.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Katya Ravid (Boston, MA) for her gift of A2BR−/− mice, Dr. Michael O'Reilly (Rochester, NY) for his gift of SP-C-eGFP transgenic mice, and Joanne Lannigan and Michael Solga from the University of Virginia FACS Core for assistance with cell sorting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong L, Medford AR, Uppington KM, Robertson J, Witherden IR, Tetley TD, Millar AB. Expression of functional toll-like receptor-2 and -4 on alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 241–245, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn MR, Lee CG, Young HW, Zhu Z, Chunn JL, Kang MJ, Banerjee SK, Elias JA. Adenosine mediates IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling in the lung and interacts in an IL-13-adenosine amplification pathway. J Clin Invest 112: 332–344, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy JP, Ruiz FE, Sorscher EJ. Adenosine and its nucleotides activate wild-type and R117H CFTR through an A2B receptor-coupled pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C361–C369, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti M, Brody AR, Harrison JH. Isolation and primary culture of murine alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 14: 309–315, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Laucher S, Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor dampens hypoxia-induced vascular leak. Blood 111: 2024–2035, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 3301–3315, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehrenbach H Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir Res 2: 33–46, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 53: 527–552, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Z, Chen T, Weber MJ, Linden J. A2B adenosine and P2Y2 receptors stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in human embryonic kidney-293 cells. Cross-talk between cyclic AMP and protein kinase c pathways. J Biol Chem 274: 5972–5980, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilfillan AM, Rooney SA. Functional evidence for adenosine A2 receptor regulation of phosphatidylcholine secretion in cultured type II pneumocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 241: 907–914, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gobran LI, Rooney SA. Regulation of SP-B and SP-C secretion in rat type II cells in primary culture. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1413–L1419, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang P, Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Milgram SL, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Compartmentalized autocrine signaling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator at the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14120–14125, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeyaseelan S, Manzer R, Young SK, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Mason RJ, Worthen GS. Induction of CXCL5 during inflammation in the rodent lung involves activation of alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 531–539, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YC, Ji X, Melman N, Linden J, Jacobson KA. Anilide derivatives of an 8-phenylxanthine carboxylic congener are highly potent and selective antagonists at human A(2B) adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 43: 1165–1172, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarowski ER, Mason SJ, Clarke L, Harden TK, Boucher RC. Adenosine receptors on human airway epithelia and their relationship to chloride secretion. Br J Pharmacol 106: 774–782, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manzer R, Wang J, Nishina K, McConville G, Mason RJ. Alveolar epithelial cells secrete chemokines in response to IL-1beta and lipopolysaccharide but not to ozone. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 158–166, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason RJ Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology 11: S12–S15, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice WR, Hull WM, Dion CA, Hollinger BA, Whitsett JA. Activation of cAMP dependent protein kinase during surfactant release from type II pneumocytes. Exp Lung Res 9: 135–149, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollins BM, Burn M, Coakley RD, Chambers LA, Hirsh AJ, Clunes MT, Lethem MI, Donaldson SH, Tarran R. A2B adenosine receptors regulate the mucus clearance component of the lung's innate defense system. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 39: 190–197, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rooney SA Regulation of surfactant secretion. In: Lung Surfactant: Cellular and Molecular Processing, edited by Rooney SA. Austin, TX: R. G. Landes Company, 1998, p. 139–163.

- 21.Roper JM, Staversky RJ, Finkelstein JN, Keng PC, O'Reilly MA. Identification and isolation of mouse type II cells on the basis of intrinsic expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L691–L700, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. Cross-talk between G(s)- and G(q)-coupled pathways in regulation of interleukin-4 by A(2B) adenosine receptors in human mast cells. Mol Pharmacol 70: 727–735, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo JD. Allometric relationships of cell numbers and size in the mammalian lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 6: 235–243, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan GW, Linden J, Buster BL, Scheld WM. Neutrophil A2A adenosine receptor inhibits inflammation in a rat model of meningitis: synergy with the type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitor, rolipram. J Infect Dis 180: 1550–1560, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorley AJ, Ford PA, Giembycz MA, Goldstraw P, Young A, Tetley TD. Differential regulation of cytokine release and leukocyte migration by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated primary human lung alveolar type II epithelial cells and macrophages. J Immunol 178: 463–473, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderbilt JN, Mager EM, Allen L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish J, Gonzalez R, Dobbs LG. CXC chemokines and their receptors are expressed in type II cells and upregulated following lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29: 661–668, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang D, Koupenova M, McCrann DJ, Kopeikina KJ, Kagan HM, Schreiber BM, Ravid K. The A2b adenosine receptor protects against vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 792–796, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang D, Zhang Y, Nguyen HG, Koupenova M, Chauhan AK, Makitalo M, Jones MR, St Hilaire C, Seldin DC, Toselli P, Lamperti E, Schreiber BM, Gavras H, Wagner DD, Ravid K. The A2B adenosine receptor protects against inflammation and excessive vascular adhesion. J Clin Invest 116: 1913–1923, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yee M, Vitiello PF, Roper JM, Staversky RJ, Wright TW, Grath-Morrow SA, Maniscalco WM, Finkelstein JN, O'Reilly MA. Type II epithelial cells are critical target for hyperoxia-mediated impairment of postnatal lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L1101–L1111, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Maa T, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Zeng D. A(2B) adenosine receptors increase cytokine release by bronchial smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30: 118–125, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Maa T, Zeng D. Synergy between A2B adenosine receptors and hypoxia in activating human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 2–8, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong H, Wu Y, Belardinelli L, Zeng D. A2B adenosine receptors induce IL-19 from bronchial epithelial cells, resulting in TNF-alpha increase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 35: 587–592, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]