Abstract

Excess retinoic acid (RA) signaling can be teratogenic and result in cardiac birth defects, but the cellular and molecular origins of these defects are not well understood. Excessive RA signaling can completely eliminate heart formation in the zebrafish embryo. However, atrial and ventricular cells are differentially sensitive to more modest increases in RA signaling. Increased Hox activity, downstream of RA signaling, causes phenotypes similar to those resulting from excess RA. These results suggest that Hox activity mediates the differential effects of ectopic RA on atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes and may underlie the teratogenic effects of RA on the heart.

Keywords: zebrafish, retinoic acid, teratogen, hox, heart

Introduction

Control of exposure to retinoic acid (RA) is important for normal heart development, since excess RA is teratogenic, resulting in cardiac defects in humans and model organisms (Lammer et al., 1985; Mark et al., 2006; Pan and Baker, 2007). In humans, excess RA exposure can cause retinoic acid embryopathy, which includes conotruncal malformations such as transposition of the great vessels, double outlet right ventricle, and tetralogy of Fallot (Lammer et al., 1985). The mechanisms underlying the teratogenic effects of RA on the heart are not well understood.

Previous studies have led to the proposal that ectopic RA treatment promotes atrial chamber identity at the expense of ventricular chamber identity (Hochgreb et al., 2003; Simoes-Costa et al., 2005), suggesting a possible mechanism underlying the teratogenic effects of RA on the ventricular and outflow regions. Multiple studies have found that addition of RA results in smaller ventricles and larger atria in chick embryos (Osmond et al., 1991; Yutzey et al., 1994; Hochgreb et al., 2003). Similarly, Stainier and Fishman (1992) found that addition of ectopic RA to zebrafish embryos resulted in formation of small hearts with more atrial than ventricular tissue. However, none of these studies resolved whether the consequences of ectopic RA represented a transformation of ventricular cells into atrial cells.

Since RA signaling molds positional identity through regulation of Hox gene expression, (Marletaz et al., 2006) it has also been proposed that Hox genes function in cardiac patterning. Searcy and Yutzey (1998) found that treatment with RA can induce the expression of multiple Hox genes in the heart fields of chick embryos. More recently, it has been proposed that Hox genes may be key effectors through which RA signaling restricts the second heart field in mouse embryos (Ryckebusch et al., 2008). Despite these correlations, the effects of increased Hox activity on the heart have not been characterized.

We sought to better understand the mechanisms underlying the teratogenic effects of ectopic RA on the formation of atrial and ventricular chambers. Using the zebrafish embryo, we first chose to revisit prior experiments (Stainier and Fishman, 1992), using molecular markers and cell counting techniques that were not available when the initial work was performed. We find that excess RA signaling results in the loss of both atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes, although the two lineages have differential sensitivity to levels of RA. Strikingly, increased Hox activity mimics the effects of ectopic RA, suggesting that Hox genes are key downstream effectors of the impact of RA on the heart. Altogether, this study provides a new perspective on the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the teratogenic effects of RA.

Results

Ectopic RA can eliminate both atrial and ventricular cells

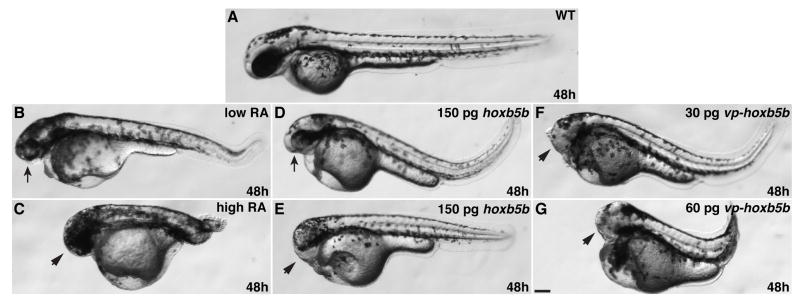

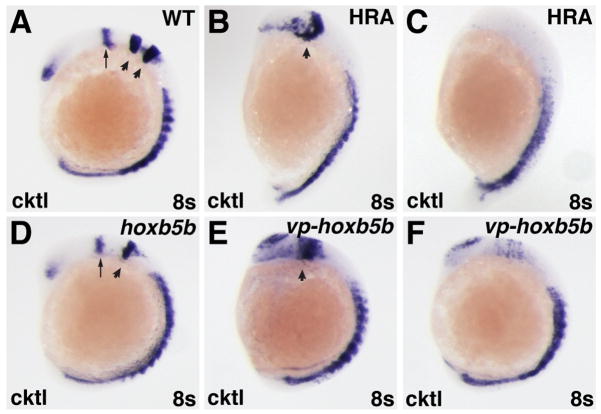

We administered varying concentrations of RA to wild-type zebrafish embryos for 1 hour beginning at the 40% epiboly stage, just before gastrulation initiates. These treatments caused concentration-dependent posteriorization of the embryonic axis (Fig. 1A–C), in accordance with prior studies (Stainier and Fishman, 1992; Minucci et al., 1996). Treatment with a low concentration of RA (“low RA”) resulted in moderately posteriorized embryos characterized by small heads and eyes (Fig. 1B). Low RA also caused loss of the anterior hindbrain and rhombomere 3 without eliminating the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (MHB) (JSW and DY, unpublished data), consistent with what has been shown previously for modest increases of RA signaling (Hernandez et al., 2007). A high concentration of RA (“high RA”) resulted in strongly posteriorized embryos characterized by tail truncation and reduction or absence of anterior central nervous system (CNS) structures (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2B,C).

Figure 1.

Increased RA signaling and Hox activity cause similar body axis phenotypes. (A) Wild-type embryo. (B) Low RA causes reduction of anterior head. (C) High RA causes loss of anterior head and tail truncation. (D and E) Injection of 150 pg of hoxb5b mRNA causes reduction or loss of anterior head. (F) 30 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA causes loss of anterior head. (G) 60 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA causes loss of anterior head and tail truncation. All images are at 48 hpf with anterior to the left. Arrows indicate reduced head and eyes. Arrowheads indicate loss of anterior head. Scale bar equals 100 μM.

Figure 2.

Increased RA signaling and Hox activity have similar effects on the anterior CNS. (A–F) In situ hybridizations at the 8-somite stage with a cocktail (cktl) of probes including pax2a (eye and MHB), krox-20/egr2b (rhombomeres 3 and 5), and myod (somites). (B,C,E,F) High RA treatment (HRA) or injection with 60 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA cause severe posteriorization phenotypes that vary between individual embryos. (B,E) High RA treatment and 60 pg vp-hoxb5b mRNA injection can truncate the anterior CNS, eliminate the MHB, and dramatically expand the posterior hindbrain. (C, F) High RA treatment and 60 pg vp-hoxb5b mRNA injection can also dramatically reduce or eliminate anterior CNS markers. (D) 150 pg hoxb5b mRNA injection causes loss of rhombomere 3, consistent with what has been shown previously for hoxb5b mRNA injection and for modest increases in RA signaling (Bruce et al., 2001; Hernandez et al., 2007). All images are lateral views, with dorsal to the right and anterior up. Arrows in A and D indicate MHB. Arrowheads in A indicate rhombomeres 3 and 5. Arrowheads in B, D, and E indicate rhombomere 5.

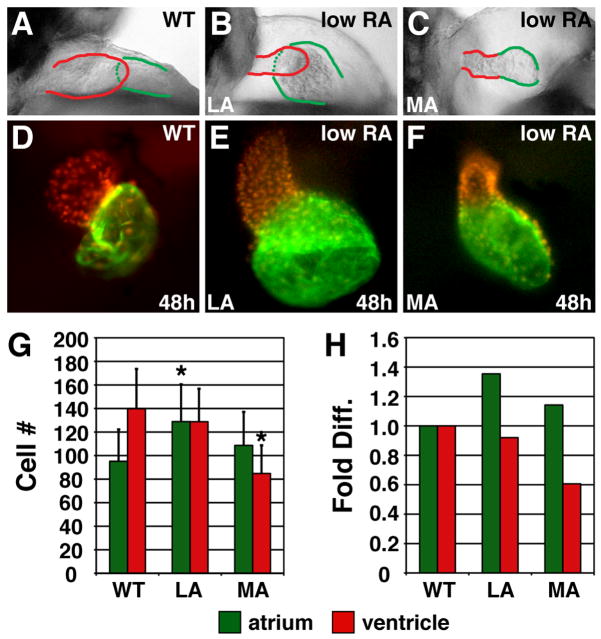

We found a variety of cardiac phenotypes in embryos treated with low RA (Fig. 3A–F). We classified these hearts into two groups based on morphology at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf): “less affected” (LA) hearts with thin ventricles and dilated atria (Fig. 3B,E), and “more affected” (MA) hearts with greatly reduced ventricles (Fig. 3C,F). Counting the cardiomyocytes in LA hearts revealed that they had an increased number of atrial cells and a normal number of ventricular cells, despite their dysmorphic ventricles (Fig. 3G,H). MA hearts, however, exhibited a normal number of atrial cells and a reduction in the number of ventricular cells (Fig. 3G,H).

Figure 3.

Excess RA signaling independently affects atrial and ventricular cell number. (A–C) Lateral views of hearts at 48 hpf; red and green outlines indicate ventricle and atrium, respectively. (D–F) Frontal views of Tg(cmlc2:DsRed2-nuc) (Mably et al., 2003) hearts, displaying nuclear DsRed in all cardiomyocytes, with Amhc immunofluorescence (green). (G) Mean (±SD) number of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes. WT, n=22; LA, n=45; MA, n=26. (H) Fold difference of the means in G. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from WT (p<0.005, Student’s t-test).

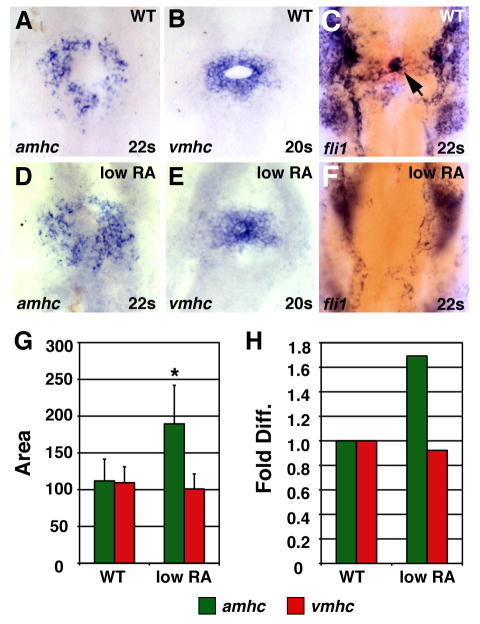

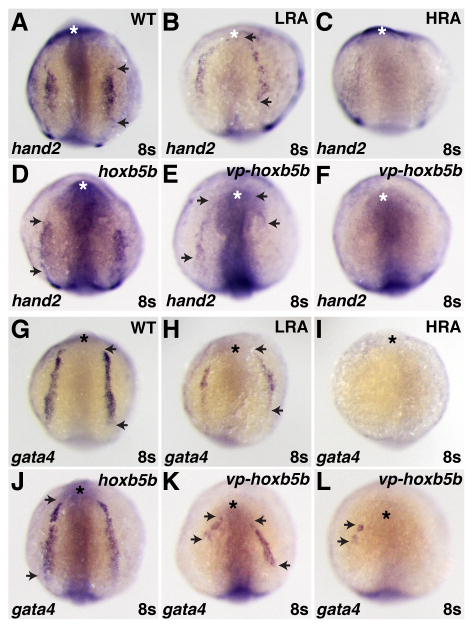

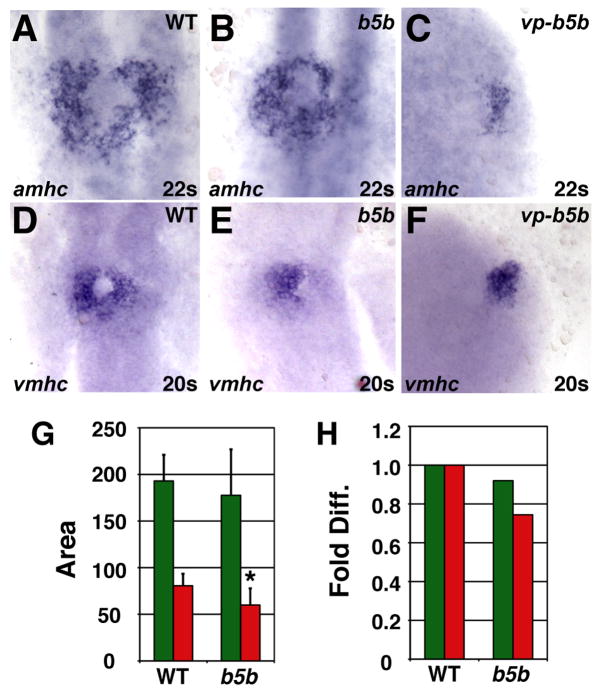

Differential effects on atrial and ventricular lineages were also evident when we examined expression of the earliest known chamber-specific genes, atrial myosin heavy chain (amhc) and ventricular myosin heavy chain (vmhc) (Yelon et al., 1999; Berdougo et al., 2003). Although we cannot distinguish LA from MA hearts prior to chamber formation, we found that low RA treatment increased the amount of amhc-expressing cells (Fig. 4A,D,G,H), without significantly disrupting the amount of vmhc-expressing cells (Fig. 4B,E,G,H). Additionally, we observed aberrant organization of vmhc-expressing cells in RA-treated embryos (Fig. 4B,E). Normally, vmhc-expressing cells encircle the endocardial precursors (Fig. 4B,C) (Stainier et al., 1993; Yelon et al., 1999; Holtzman et al., 2007), but these precursors appeared absent in RA-treated embryos (Fig. 4E,F). The endocardial progenitors arise from the region adjacent and anterior to the cardiac progenitors in the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM) at the 8 somite stage (Schoenebeck et al., 2007). This loss of endocardial cells at the 22 somite stage correlates with the reduced expression and anterior shift of the ALPM markers hand2 and gata4 in RA-treated embryos at the 8 somite stage (Fig. 5A,B,G,H).

Figure 4.

Low RA treatment can cause an increase in amhc expression. (A–F) In situ hybridizations at the 20 somite or 22 somite stage; dorsal views, anterior up. Arrow in C indicates endocardial precursors. (G) Mean (±SD) of areas of amhc and vmhc expression. WT amhc, n=43; WT vmhc, n=31; low RA amhc, n=18; low RA vmhc, n= 25. (H) Fold difference in means in G. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences from WT (p<0.005, Student’s t-test).

Figure 5.

Increased RA signaling and Hox activity have similar effects on the ALPM. (A–L) In situ hybridizations of hand2 (A–F) and gata4 (G–L) in RA-treated, hoxb5b mRNA-injected, and vp-hoxb5b mRNA-injected embryos at the 8 somite stage. (D) 150 pg hoxb5b mRNA injection can cause a slight anterior shift in hand2 expression in the LPM. (B,E,H,K) Low RA (LRA) treatment or injection of 30 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA can shift hand2 anteriorly and reduce the length of gata4 expression. The uneven effects on either side of the embryo are likely due to mosaic distribution of the injected mRNA. (C,F,I,L) High RA (HRA) treatment or injection of 60 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA can eliminate hand2 and gata4 expression. All views are dorsal with anterior up. Asterisks indicate the anterior head. Arrowheads indicate the anterior and posterior borders of expression in the LPM.

High RA treatment caused more dramatic cardiac phenotypes: 100% (22/22) of embryos lacked hearts at 48 hpf, 100% (14/14) lacked gata4 expression (Fig. 5I), and 70% (14/20) lacked hand2 expression in the ALPM at the 8 somite stage (Fig. 5C). In high RA-treated embryos, both atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes were absent at the 20–22 somite stage: 73% (11/15) lacked amhc expression, and 97% (36/37) lacked vmhc expression. Together, these results suggest that moderate increases in RA signaling eliminate portions of the ALPM while having differential effects on atrial and ventricular cells and that high increases in RA signaling can eliminate both atrial and ventricular cells.

Increased Hox activity mimics the effects of RA treatment

To examine the effects of increased Hox activity on the heart, we overexpressed zebrafish Hoxb5b. While overexpression of a number of hox genes may have essentially equivalent effects (Bruce et al., 2001; Shimizu et al., 2006; Rohrschneider et al., 2007), we selected hoxb5b because its expression is positively regulated by and is likely a direct target of RA signaling (Jarinova et al., 2008; Waxman et al., 2008), as is the case for its mammalian ortholog hoxb5 (Sharpe et al., 1998; Oosterveen et al., 2003). Injection of mRNA encoding either wild-type hoxb5b or a hyperactive VP16-tagged hoxb5b (vp-hoxb5b) (Waxman et al., 2008) resulted in phenotypes reminiscent of RA treatment (Fig. 1). Injection of hoxb5b mRNA (150 pg) resulted in embryos with reduced or absent anterior heads (Fig. 1D,E). Furthermore, injection of hoxb5b mRNA caused loss of rhombomere 3 (Fig. 2A,D), consistent with what has been shown previously for hoxb5b overexpression (Bruce et al., 2001) and similar to what is observed for low RA treatment (JSW and DY, unpublished data; Hernandez et al., 2007). Injection of 30 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA resulted in loss of anterior head without significant tail shortening (Fig. 1F), comparable to 150 pg of hoxb5b mRNA. However, 60 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA caused shortening of the body axis, reminiscent of high RA treatment (Fig. 1G). In addition to the general morphological phenotypes at later stages, higher amounts of vp-hoxb5b mRNA caused phenotypes ranging from an expansion of the posterior hindbrain to almost complete loss of anterior CNS markers (Fig. 2E,F), trends reminiscent of high RA treatment (Fig. 2B,C). Despite the similarity of effects on CNS markers and the shortened body axis observed later, embryos injected with hoxb5b or vp-hoxb5b mRNA typically did not have elongated bodies at the 8 somite stage, as was observed in RA-treated embryos (Fig. 2B–F). Therefore, increased Hox activity can phenocopy many of the general body axis and CNS defects caused by ectopic RA.

Increased Hox activity reduces the numbers of atrial and ventricular cells

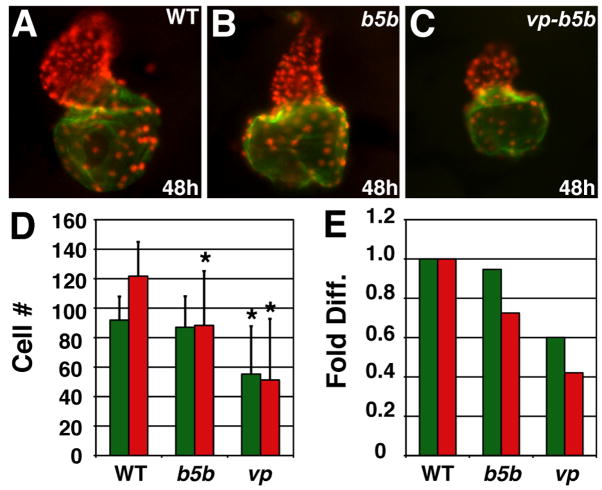

Examination of the hearts of hoxb5b-injected embryos revealed dysmorphic and small ventricles with relatively normally sized atria (Fig. 6B,D,E), comparable to the features of MA hearts (Fig. 3F,G,H). Similar effects on ventricular and atrial populations were reflected by the vmhc and amhc expression patterns in hoxb5b-injected embryos at the 20–22 somite stage (Fig. 7B,E,G,H). However, at the 8 somite stage, gata4 and hand2 expression were relatively unaffected, though hand2 was occasionally located slightly more anteriorly than in wild-type embryos (Fig. 5A,D,G,J). Embryos injected with either 30 or 60 pg vp-hoxb5b mRNA exhibited more severe cardiac reduction. At the 8 somite stage, hand2 expression was shifted anteriorly or eliminated (Fig. 5E,F) and gata4 expression was reduced or eliminated (Fig. 5K,L), which was highly reminiscent of the effects of RA treatment (Fig. 5B,C,H,I). However, relative to high RA treatment, hearts were less frequently eliminated in embryos injected with 60 pg vp-hoxb5b mRNA, despite their severe posteriorization: 73% (11/15) of embryos injected with 60 pg of vp-hoxb5b mRNA had hearts. Despite the lesser potency of vp-hoxb5b mRNA to completely eliminate the hearts, the number of cells in both chambers was severely reduced at all stages examined (Fig. 6C,D,E and Fig. 7C,F). Thus, our results suggest that atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes are differentially sensitive to increased Hox activity, although excessive Hox activity can reduce the numbers of both cell types. Together, these phenotypes mimic the effects of ectopic RA on the heart.

Figure 6.

Increased Hox activity reduces atrial and ventricular cell number. (A–C) Hearts from WT, hoxb5b mRNA-injected (150 pg), and vp-hoxb5b mRNA-injected (60 pg) embryos. (D) Mean (±SD) number of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes. WT, n=25; hoxb5b mRNA, n=30; vp-hoxb5b mRNA, n=42. (E) Fold difference of means in D. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from WT (p<0.005, Student’s t-test). All views and graphs are as presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 7.

Increased Hox activity reduces amhc and vmhc expression. (A–F) Cardiomyocytes from WT, hoxb5b mRNA-injected (150 pg), and vp-hoxb5b mRNA-injected (60 pg) embryos. (G) Mean (±SD) of areas of amhc and vmhc expression. WT amhc, n=48; hoxb5b mRNA amhc, n=53; WT vmhc, n=59; hoxb5b mRNA vmhc, n=53. (H) Fold difference of means in G. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference from WT (p<0.005, Student’s t-test). All views and graphs are as presented in Fig. 4.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that excess RA signaling causes differential effects on atrial and ventricular cells, trends mimicked by increased Hox activity. High RA treatment can eliminate both atrial and ventricular cells, although ventricular cells are more susceptible to these concentrations of ectopic RA. These observations are consistent with a role of RA signaling in limiting the number of cardiomyocytes (Keegan et al., 2005; Ryckebusch et al., 2008; Waxman et al., 2008). Low RA treatment also appears to affect ventricular and atrial populations independently: it can cause a mild phenotype featuring an expansion of atrial cells without a reduction of ventricular cells or a stronger phenotype featuring a loss of ventricular cells without much effect on atrial cells. Importantly, neither trend supports the previously suggested role of RA in promoting atrial identity through transformation of ventricular identity (Hochgreb et al., 2003; Simoes-Costa et al., 2005).

Hox genes have been suggested as the key downstream effectors of RA signaling during cardiac patterning (Searcy and Yutzey, 1998; Ryckebusch et al., 2008). In support of this hypothesis, we recently found that hoxb5b is required downstream of RA signaling to restrict cardiac cell number in zebrafish: hoxb5b expression is positively regulated by RA signaling, and loss of hoxb5b function results in the formation of too many atrial cardiomyocytes (Waxman et al., 2008). Here, through overexpression experiments, we demonstrate that the effects of increased hoxb5b activity are remarkably similar to those of increased RA signaling. In addition to affecting cardiac cell number, both increased Hox activity and increased RA signaling reduce or eliminate the expression of ALPM markers. The anterior shift of ALPM marker expression observed in some embryos is reminiscent of trends reported for RA-treated Xenopus embryos, which display hearts shifted toward the anterior (Collop et al., 2006).

With respect to the effects of increased Hox activity on the individual chambers, modest increases in Hoxb5b activity reduce ventricular cell number, whereas further increases in Hoxb5b activity reduce the numbers of both atrial and ventricular cells. While we did not find that hoxb5b mRNA injection could increase atrial cell number, the differences between the consequences of increased RA signaling and Hoxb5b activity could be due to technical distinctions between the effectiveness of RA exposure and RNA injection. Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that RA signaling regulates numerous hox genes (Marletaz et al., 2006; JSW and DY, data not shown). Overexpression of some of these hox genes has posteriorizing effects on the CNS, similar to the effects of overexpressing hoxb5b (Bruce et al., 2001; Shimizu et al., 2006; Rohrschneider et al., 2007). While it is feasible that the consequences of overexpression of one hox gene are overtly equivalent to overexpression of multiple hox genes, it is also possible that increasing the expression of multiple hox genes simultaneously has subtly different teratogenic effects than overexpression of a single hox gene. Therefore, we speculate that the full spectrum of teratogenic effects of increased RA signaling is due to increased activity of multiple Hox proteins.

Despite the similarities of ectopic RA signaling and Hox overexpression, it is important to recognize that neither represents the inverse of the respective loss of function. In zebrafish, loss of RA signaling results in increased numbers of both atrial and ventricular cells (Waxman et al., 2008), and the highest increases in RA signaling can eliminate both of these cell types. However, moderate increases in RA signaling do not follow this trend and can differentially affect atrial and ventricular lineages, increasing atrial but not ventricular cell number. With respect to Hox activity, we have found in loss-of-function experiments that hoxb5b is required to restrict atrial cell number (Waxman et al., 2008), yet increasing Hox activity can eliminate both atrial and ventricular cells. Together, these data suggest that the mechanisms of the teratogenic effects of increased RA signaling may be different than the inverse of the endogenous requirements for RA signaling. One potential reason for this mechanistic difference could be autonomous affects of increased RA and Hox activity on cardiac progenitors compared to non-autonomous requirements of RA signaling and an effector like hoxb5b (Waxman et al., 2008). The notion that the teratogenic molecular mechanism of increased RA signaling may not reflect the inverse of the requirement for endogenous RA signaling is compatible with a number of other studies of RA signaling during mouse development, such as those examining the pharynx (for review see Mark et al., 2006).

The lack of inverse relationship between the teratogenic effects of ectopic RA and the endogenous requirements for RA is also evident in the endocardium. While moderate increases in RA signaling seem to eliminate the endocardium, loss of RA signaling does not create an obvious excess of endocardium (JSW and DY, unpublished data) nor does it affect the number of endocardial progenitor cells (Keegan et al., 2005). The loss of endocardial cells may be connected to the loss of anterior tissues caused by ectopic RA signaling and Hox activity, since endocardial progenitors originate from the most anterior portion of the ALPM (Schoenebeck et al., 2007). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that ectopic RA signaling affects the ability of the endocardial progenitors to migrate to the embryonic midline, instead of inhibiting their specification.

Altogether, this study provides new suggestions regarding the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the teratogenic effects of ectopic RA. Recent studies in mice have indicated that RA signaling is required to restrict the size of the second heart field, while not having the same impact on the primary heart field (Ryckebusch et al., 2008; Sirbu et al., 2008). It is therefore tempting to speculate that the differential sensitivity of cardiac lineages to increased RA signaling could also be a conserved property. The differential sensitivity of ventricular and atrial lineages to RA in zebrafish might relate to the particular sensitivity of the conotruncal region to RA exposure in humans (Lammer et al., 1985). Furthermore, we propose that dysregulated Hox activity may be an underlying cause of RA-induced cardiac teratogenicity.

Experimental Procedures

RA treatments

We define a low concentration of all-trans-RA (R2625, Sigma) as 0.1 μM and a high concentration as 0.3 μM. Groups of 25–30 embryos at 40% epiboly were treated with RA for 1 hour under low light in glass vials. This method of treatment causes similar phenotypes to continuous treatment with RA, but phenotypes induced by continuous treatment are more severe (JSW and DY, unpublished data).

In situ hybridization, immunofluorescence and cell counting

In situ hybridization for atrial myosin heavy chain (amhc) and ventricular myosin heavy chain (vmhc) was performed as previously described (Berdougo et al., 2003). pax2a, krox20/egr2b, myod, hand2, and gata4 probes have been reported previously (Oxtoby and Jowett, 1993; Strahle et al., 1993; Weinberg et al., 1996; Serbedzija et al., 1998; Yelon et al., 2000). Immunofluoresence and cell counting were done as previously described (Waxman et al., 2008). For area measurements and cell counts, embryos were compared to control siblings processed simultaneously. Control values in Figures 3 and 4 were also reported previously (Waxman et al., 2008), because experiments here were performed in tandem with those prior experiments.

Embryo injections

Zebrafish embryos were injected at the one cell stage with capped mRNA made with a Message Machine Kit (Ambion). Both hoxb5b and vp-hoxb5b were cloned into pCS2p+ as previously described (Waxman et al., 2008).

Acknowledgments

NHLBI/NIH; Grant numbers: R01 HL069594, F32 HL083591, and K99 HL091126

We thank members of the Yelon laboratory for helpful input. Support was provided by NIH F32 HL083591 (to JSW), NIH K99 HL091126 (to JSW), and NIH R01 HL069594 (to DY).

References

- Berdougo E, Coleman H, Lee DH, Stainier DY, Yelon D. Mutation of weak atrium/atrial myosin heavy chain disrupts atrial function and influences ventricular morphogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:6121–6129. doi: 10.1242/dev.00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce AE, Oates AC, Prince VE, Ho RK. Additional hox clusters in the zebrafish: divergent expression patterns belie equivalent activities of duplicate hoxB5 genes. Evol Dev. 2001;3:127–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collop AH, Broomfield JA, Chandraratna RA, Yong Z, Deimling SJ, Kolker SJ, Weeks DL, Drysdale TA. Retinoic acid signaling is essential for formation of the heart tube in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2006;291:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez RE, Putzke AP, Myers JP, Margaretha L, Moens CB. Cyp26 enzymes generate the retinoic acid response pattern necessary for hindbrain development. Development. 2007;134:177–187. doi: 10.1242/dev.02706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochgreb T, Linhares VL, Menezes DC, Sampaio AC, Yan CY, Cardoso WV, Rosenthal N, Xavier-Neto J. A caudorostral wave of RALDH2 conveys anteroposterior information to the cardiac field. Development. 2003;130:5363–5374. doi: 10.1242/dev.00750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman NG, Schoenebeck JJ, Tsai HJ, Yelon D. Endocardium is necessary for cardiomyocyte movement during heart tube assembly. Development. 2007;134:2379–2386. doi: 10.1242/dev.02857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarinova O, Hatch G, Poitras L, Prudhomme C, Grzyb M, Aubin J, Berube-Simard FA, Jeannotte L, Ekker M. Functional resolution of duplicated hoxb5 genes in teleosts. Development. 2008;135:3543–3553. doi: 10.1242/dev.025817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan BR, Feldman JL, Begemann G, Ingham PW, Yelon D. Retinoic acid signaling restricts the cardiac progenitor pool. Science. 2005;307:247–249. doi: 10.1126/science.1101573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, Agnish ND, Benke PJ, Braun JT, Curry CJ, Fernhoff PM, Grix AW, Jr, Lott IT, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:837–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mably JD, Mohideen MA, Burns CG, Chen JN, Fishman MC. heart of glass regulates the concentric growth of the heart in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2138–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Function of retinoid nuclear receptors: lessons from genetic and pharmacological dissections of the retinoic acid signaling pathway during mouse embryogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:451–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marletaz F, Holland LZ, Laudet V, Schubert M. Retinoic acid signaling and the evolution of chordates. Int J Biol Sci. 2006;2:38–47. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.2.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minucci S, Saint-Jeannet JP, Toyama R, Scita G, DeLuca LM, Tiara M, Levin AA, Ozato K, Dawid IB. Retinoid X receptor-selective ligands produce malformations in Xenopus embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1803–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveen T, Niederreither K, Dolle P, Chambon P, Meijlink F, Deschamps J. Retinoids regulate the anterior expression boundaries of 5′ Hoxb genes in posterior hindbrain. Embo J. 2003;22:262–269. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond MK, Butler AJ, Voon FC, Bellairs R. The effects of retinoic acid on heart formation in the early chick embryo. Development. 1991;113:1405–1417. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby E, Jowett T. Cloning of the zebrafish krox-20 gene (krx-20) and its expression during hindbrain development. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Baker KM. Retinoic acid and the heart. Vitam Horm. 2007;75:257–283. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)75010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrschneider MR, Elsen GE, Prince VE. Zebrafish Hoxb1a regulates multiple downstream genes including prickle1b. Dev Biol. 2007;309:358–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckebusch L, Wang Z, Bertrand N, Lin SC, Chi X, Schwartz R, Zaffran S, Niederreither K. Retinoic acid deficiency alters second heart field formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2913–2918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712344105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenebeck JJ, Keegan BR, Yelon D. Vessel and blood specification override cardiac potential in anterior mesoderm. Dev Cell. 2007;13:254–267. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy RD, Yutzey KE. Analysis of Hox gene expression during early avian heart development. Dev Dyn. 1998;213:82–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199809)213:1<82::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, Chen JN, Fishman MC. Regulation in the heart field of zebrafish. Development. 1998;125:1095–1101. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe J, Nonchev S, Gould A, Whiting J, Krumlauf R. Selectivity, sharing and competitive interactions in the regulation of Hoxb genes. Embo J. 1998;17:1788–1798. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Bae YK, Hibi M. Cdx-Hox code controls competence for responding to Fgfs and retinoic acid in zebrafish neural tissue. Development. 2006;133:4709–4719. doi: 10.1242/dev.02660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes-Costa MS, Vasconcelos M, Sampaio AC, Cravo RM, Linhares VL, Hochgreb T, Yan CY, Davidson B, Xavier-Neto J. The evolutionary origin of cardiac chambers. Dev Biol. 2005;277:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbu IO, Zhao X, Duester G. Retinoic acid controls heart anteroposterior patterning by down-regulating Isl1 through the Fgf8 pathway. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1627–1635. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainier DY, Fishman MC. Patterning the zebrafish heart tube: acquisition of anteroposterior polarity. Dev Biol. 1992;153:91–101. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90094-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainier DY, Lee RK, Fishman MC. Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. I. Myocardial fate map and heart tube formation. Development. 1993;119:31–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahle U, Blader P, Henrique D, Ingham PW. Axial, a zebrafish gene expressed along the developing body axis, shows altered expression in cyclops mutant embryos. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1436–1446. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman JS, Keegan BR, Roberts RW, Poss KD, Yelon D. Hoxb5b acts downstream of retinoic acid signaling in the forelimb field to restrict heart field potential in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2008;15:923–934. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ES, Allende ML, Kelly CS, Abdelhamid A, Murakami T, Andermann P, Doerre OG, Grunwald DJ, Riggleman B. Developmental regulation of zebrafish MyoD in wild-type, no tail and spadetail embryos. Development. 1996;122:271–280. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D, Horne SA, Stainier DY. Restricted expression of cardiac myosin genes reveals regulated aspects of heart tube assembly in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 1999;214:23–37. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D, Ticho B, Halpern ME, Ruvinsky I, Ho RK, Silver LM, Stainier DY. The bHLH transcription factor hand2 plays parallel roles in zebrafish heart and pectoral fin development. Development. 2000;127:2573–2582. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutzey KE, Rhee JT, Bader D. Expression of the atrial-specific myosin heavy chain AMHC1 and the establishment of anteroposterior polarity in the developing chicken heart. Development. 1994;120:871–883. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]