Abstract

Background & Aim

Extensive evidence suggests that Akt signaling plays an important role in p-cell mass and function, although its function in the regulation of the different pancreatic fates has not been adequately investigated. The goal of these studies was to assess the role of Akt signaling in the pancreatic differentiation programs.

Methods

For these experiments, we have generated a double reporter mouse model that provides activation of Akt signaling in a cell type-specific manner. This mouse model conditionally overexpresses a constitutively active form of Akt upon Cre-mediated recombination. Activation of Akt signaling in pancreatic progenitors, acinar and β-cell was achieved by crossing this animal model to specific Cre-lines.

Results

We showed that overexpression of a constitutively active Akt in Pdx1 progenitors induced expansion of ductal structures expressing progenitor markers. This expansion resulted in part from increased proliferation of the ductal epithelium. Lineage tracing experiments in mice with activation of Akt signaling in mature acinar and β-cells suggested that acinar to ductal and p-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation also contributed to the expansion of the ductal compartment. In addition to the changes in cell plasticity, these studies demonstrated that chronic activation of Akt signaling in Pdx1 progenitors induced the development of pre-malignant lesions and malignant transformation in old mice.

Conclusions

The current work unravels some of the molecular mechanisms of cellular plasticity and reprogramming and demonstrates for the first time that activation of Akt signaling regulates the fate of differentiated pancreatic cells in vivo.

Keywords: Akt, pancreatic progenitors, transdifferentiation, plasticity, pancreatic cancer, lineage tracing

Introduction

The serine-threonine kinase Akt plays an important role in multiple biological processes including carbohydrate metabolism. Experiments in Akt2 deficient mice showed that Akt is important for β-cells 1–3. In contrast, overexpression of a constitutively active form of Akt driven by the rat insulin promoter induced β-cell mass 4, 5. Moreover, overexpression of a kinase dead mutant of Akt in β-cells results in insulin secretory defect 6. The role of this pathway in regulation of the differentiation programs of the pancreas and cell fate allocation during early steps of development and plasticity of differentiated cells has not been established.

The balance between differentiation and self-renewal of progenitors is a major step in the differentiation programs of different tissues. Evidence implicating PI3K/Akt signaling in the differentiation of the pancreas comes from in vitro experiments. Inhibition of PI3K signaling in human fetal undifferentiated cells induced morphological and functional endocrine differentiation 7. In vitro treatment of mouse embryonic stem cells with PI3K inhibitors produced cells that resembled β-cells 8. The balance between self-renewal and developmental programs has been associated with carcinogenesis. Several lines of evidence indicate that the PI3K/Akt signaling plays an important role in pancreatic ductal carcinoma (PDA) 9. Akt activators such as Kras, Shh, EGFR and PTEN have been implicated in PDA 10–13. While these data indirectly implicated Akt signaling in all these processes, it is unclear whether in vivo activation of this pathway regulates the differentiation programs of the pancreas and plasticity of differentiated cells.

The overall goal of these studies was to extend the previous observations in pancreatic adult p-cells by studying the role of Akt signaling in the differentiation program of the pancreas. This was achieved by performing lineage-tracing experiments in mice with activation of Akt signaling in pancreatic progenitors, acinar or β-cells. These experiments showed that activation of Akt signaling in Pdx1 progenitors induced expansion of ductal structures expressing progenitor markers and malignant transformation. In addition, activation of Akt signaling in acinar and β-cells induced acinar to ductal and β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation. These data provide evidence for a role of Akt signaling in regulation of pancreas plasticity and suggest that the activity of Akt signaling could play a critical role in maintaining the fate of mature tissues. Finally, the current work gives some insight into the role of Akt signaling during the pathogenesis of pancreatic carcinoma.

Materials & Methods

Animal generation

The PCALL2 vector contains a strong promoter with widespread expression 14 followed by a loxP-flanked stop codon β-geo (LacZ/neoR fusion protein), and enhanced green fluorescent protein (IRES-EGFP) (Figure 1A) 15. A constitutively active form of Akt (caAkt) 3 was subcloned in this vector. The transgenic animals were generated as previously described 16. These mice were crossed with mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of Pdx1 promoter (Pdx1-Cre) 17, rat Insulin promoter (RIP-Cre) 18 pdx1PB CreER™, or Elastase promoter (Elastase-Cre) 19. For the tamoxifen experiments, 4 week old Pdx1PB CreER™;caAkt and controls (Pdx1PB CreER™ and PCALL;caAkt) were intraperitoneally injected for 5 days with tamoxifen as described 20. All procedures were performed in accordance with Washington University’s Animal Studies Committee.

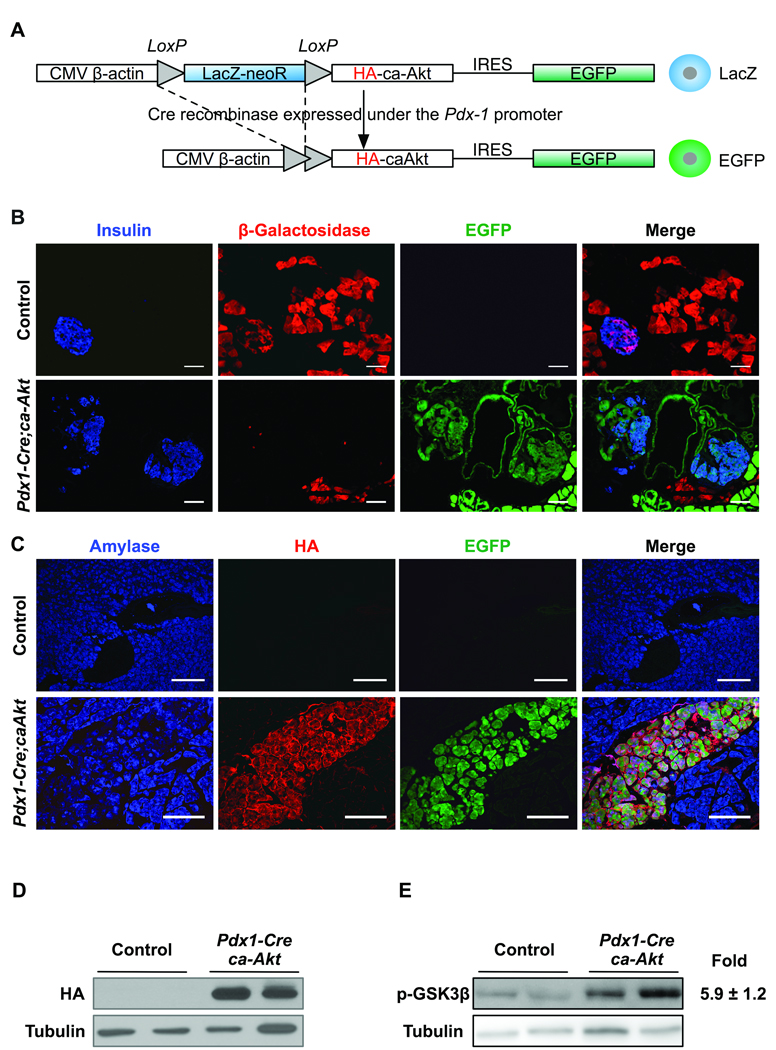

Figure 1. Generation of a dual reporter mouse with activation of Akt in a Cre-dependent manner.

(A) The transgenic construct contains a chicken β-actin promoter with upstream cytomegalovirus enhancer loxP-flanked stop codon (LacZ-neoR), HA (hemaglutinin)-tagged caAkt mutant, and enhanced green fluorescent protein (IRES-EGFP). (B) Staining for insulin (blue), β-galactosidase (red) and EGFP fluorescence (green) in 3-month-old control and Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata. (C) Transgene expression by immunofluorescence for amylase (blue), HA-tag (red), and EGFP (green). Immunoblotting for HA (D) and phospho-GSK3β (E) in pancreatic lysates from 3-month-old mice. Data is presented as mean ± S.E from three independent experiments performed in duplicates. (*p<0.05). Scale bar, 50 µm.

Immunostaining and Islet morphometry

Pancreata were fixed and embedded in paraffin or tissue freezing medium using standard techniques. Primary antibodies used are shown in supplemental methods. Hematoxylin/Eosin and Alcian Blue were performed on paraffin-embedded sections using standard techniques. Fluorescent images were analyzed as described in supplemental methods.

Electron microscopy

Pancreata were fixed overnight in a Modified Karnovsky's fixative then processed as described in supplemental methods.

Metabolic studies

Glucose tolerance and insulin levels were measured as described 5.

Western blotting

Primary antibodies used are shown in supplemental methods. Scanning densitometry of protein bands was determined by pixel intensity using NIH ImageJ software (v1.38x freely available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html) 21 and normalized using α-tubulin as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard error. Statistical analyses were conducted using unpaired, two-tailed student t tests. Differences were considered statistically significant with a p value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Generation of a dual reporter mouse model with activation of Akt signaling in Cre-dependent manner

The importance of activation of Akt signaling in β-cells has been previously assessed in transgenic mice overexpressing Akt under the control of the rat Insulin promoter 4, 5. This model however does not provide insight into the role of Akt signaling in differentiation steps prior to acquisition of the β-cell fate or the fate of other compartments. To study the role of activation of Akt signaling in the differentiation program of the pancreas, we generated a mouse model that conditionally overexpresses a constitutively active form of Akt upon Cre-mediated recombination. The construct used contains a CMV enhancer upstream of the chicken β-actin promoter that controls the expression of β-galactosidase flanked with loxP sites (LacZ-neoR) (Figure 1A). The caAkt mutant containing a hemaglutinin tag (HA) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (IRES-EGFP) were cloned downstream of the β-galactosidase (PCALL2-caAkt, Figure 1A). In these mice, removal of the loxP flanked β-galactosidase sequence triggers expression of the caAkt mutant along with EGFP (Figure 1A). Using this construct, two lines of transgenic mice with similar pattern of expression were generated. In the absence of Cre recombinase, we confirmed that only β-galactosidase was expressed in acinar, β- and ducts cells (Figure 1B, data not shown for ducts). These mice were used as controls for all experiments. To activate Akt signaling in pancreatic progenitors, PCALL2-caAkt animals were crossed to mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the Pdx1 promoter (Pdx1-Cre;caAkt). In these mice, progeny of cells that expressed Pdx1 during development will permanently express caAkt and are tagged with EGFP for lineage tracing analysis. Since Pdx1 precursors give rise to all pancreatic lineages, we anticipated finding activation of Akt signaling and EGFP expression in all compartments. As expected, three month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata exhibited EGFP fluorescence in the acinar, ductal and (3-cell compartment (Figure 1B). β-galactosidase immunostaining was still observed in ∼20% of the pancreas reflecting mosaic Cre-mediated recombination (Figure 1B). Co-expression of the caAkt mutant assessed by HA staining and EGFP was observed only in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice (Figure 1C). Similarly, HA expression by immunoblotting was only detected in lysates from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata (Figure 1D). Pancreas lysates from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice exhibited elevated levels of phosphorylated GSK3β, a downstream target of Akt (Figure 1E, Figure 5.9 +1.2, p<0.01). These observations confirmed the successful generation of a transgenic mouse that expresses caAkt in a Cre recombinase-dependent manner. While there is some mosaicism, the EGFP reporter allowed us to perform lineage-tracing analysis of the progeny of cells that expressed Pdx1-Cre.

Figure 5. Transdifferentiation of acinar to ductal cells contributes to the expansion of ductal structures observed in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals.

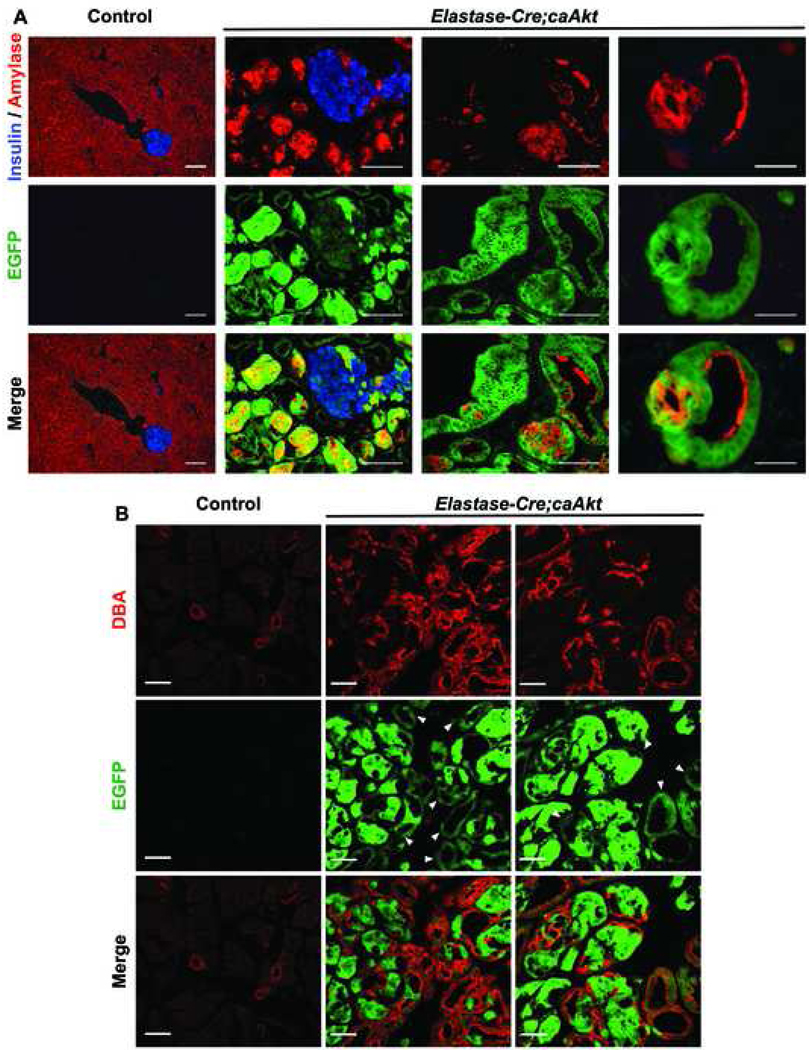

(A) Immunostaining for insulin (blue), amylase (red), with GFP (green) in 5 week-old control and Elastase-Cre;caAkt animals. (B) Confocal analysis of immunostaining for DBA (red) and EGFP fluorescence (green) in 5 week-old control and Elastase-Cre;caAkt pancreata. Arrowheads: EGFP positive ductal structures. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Expression of caAkt mutant in Pdx1 progenitors resulted in pancreatic enlargement, architecture disruption and expansion of the ductal compartment

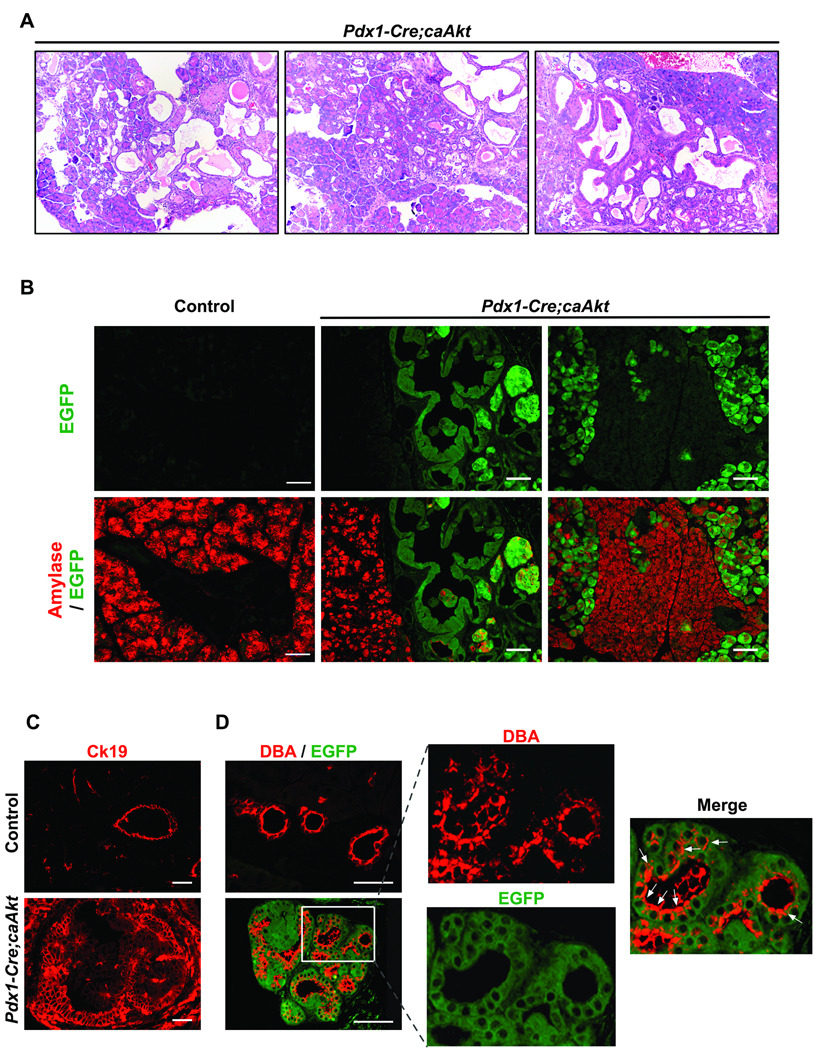

Analysis of pancreas showed increased weight in 3 month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice (250 ± 20mg in control versus 630 ± 30mg in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice, p<0.05). Gross examination revealed small transparent round cystic areas in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata (Figure S1A) with alteration in pancreatic architecture and replacement of most of the acinar tissue with ductal structures (Figure 2A and Figure S1B). The acinar compartment in control mice and GFP negative areas from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals displayed normal acinar morphology (Figure 2B). In contrast, acinar cells that were GFP positive appeared bigger with abnormal amylase staining (Figure 2B). Staining for Ck19 (ductal marker) revealed normal branched ductal morphology in control mice (Figure 2C). Ck19 staining in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt revealed pseudostratified ductal epithelium containing tall columnar cells with loss of polarity (Figure 2C). Co-staining for GFP and the ductal marker DBA 22 in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata confirmed the ductal nature of these structures (Figure 2D). Analysis in newborn Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice showed normal EGFP expressing ducts (Figure S2A). Evidence of increased ductal compartment was observed at one month of age (Figure S2B). These results suggest that expression of caAkt in pancreatic progenitors resulted in abnormal acinar architecture and progressive expansion of ductal structures.

Figure 2. Activation of caAkt in Pdx1 progenitors induces disruption of pancreatic architecture and progressive ductal expansion.

(A) Hematoxylin and Eosin stained pancreatic sections from 3-month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals. (B) Immunostaining for amylase (red) and GFP (green) on paraffin embedded sections from 3-month-old mice. (C) Immunostaining for Ck19 (red). (D) Ductal staining using lectin DBA (red) and EGFP fluorescence. Arrows; ductal-like structures expressing EGFP and DBA. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Activation of Akt signaling induced expression of progenitor markers in the ductal epithelium

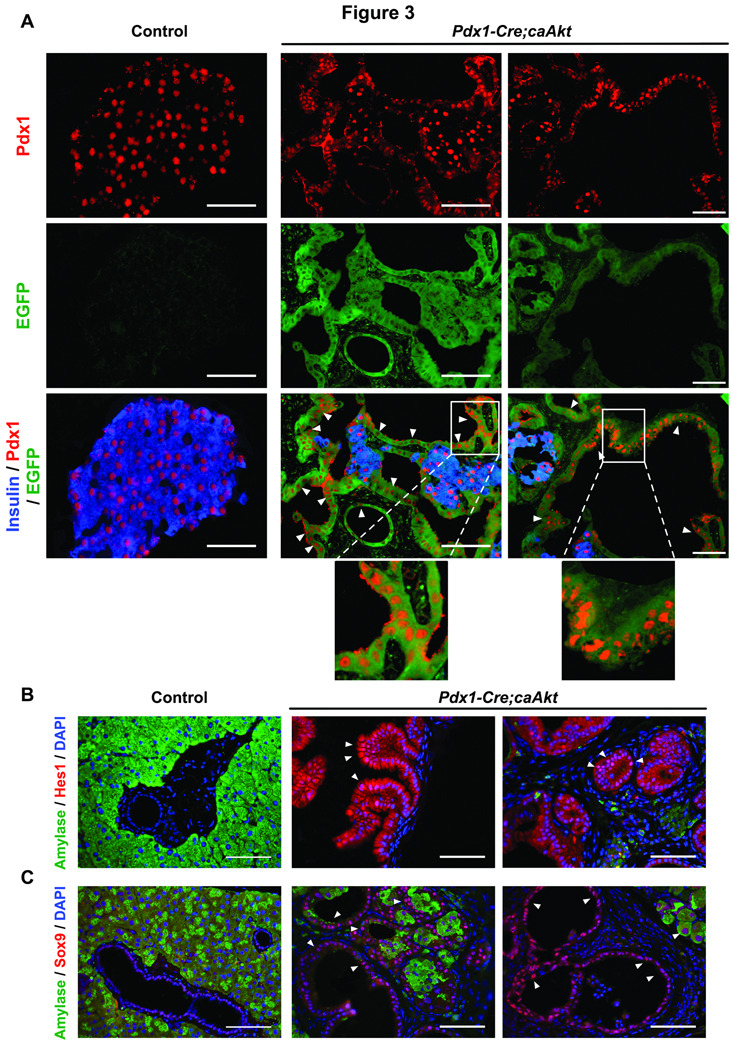

Assessment of pancreatic progenitors was performed by immunostaining for the progenitor markers, Pdx1, Hes1 and Sox9. As expected, Pdx1 expression was restricted to β-cells in control pancreata (Figure 3A). Ductal structures from three month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata were GFP positive. Pdx1 expression was present in most of the ductal epithelium and β-cells (Figure 3A). Neonates and one-month-old mice exhibited lower levels of Pdx1 expression in some of the ductal structures (Figure S2A and B). To determine activation of notch signaling, we assessed Hes1 expression. As previously described, Hes1 was undetectable in adult pancreata 23 (Figure 3B). In Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice, nuclear Hes1 staining was only detected in the epithelial cells of the ductal structures (Figure 3B). Sox9, a marker of pancreatic progenitors cells 24, 25, was observed at low levels in controls. In contrast, all the ductal structures and most of the acinar tissue from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata exhibited high Sox9 levels (Figure 3C). These experiments suggest that induction of Akt signaling in Pdx1 progenitors resulted in expansion of a pool of ductal cells expressing progenitor markers.

Figure 3. Activation of Akt signaling results in expression of progenitors markers in the ductal epithelium from adult Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice.

(A) Immunostaining for insulin (blue), Pdx1 (red) and GFP (green) in 3 month-old control and Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata. Expression of Pdx1 in the ductal structure was observed (arrowheads). (B–C) Staining for amylase (green) and Hes1 (B) or Sox9 (C) (red) in control and Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals. Arrows show Hes1 and Sox9 expressing nuclei in ductal structures. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Ductal expansion resulted from proliferation of the ductal epithelium and acinar to ductal transdifferentiation

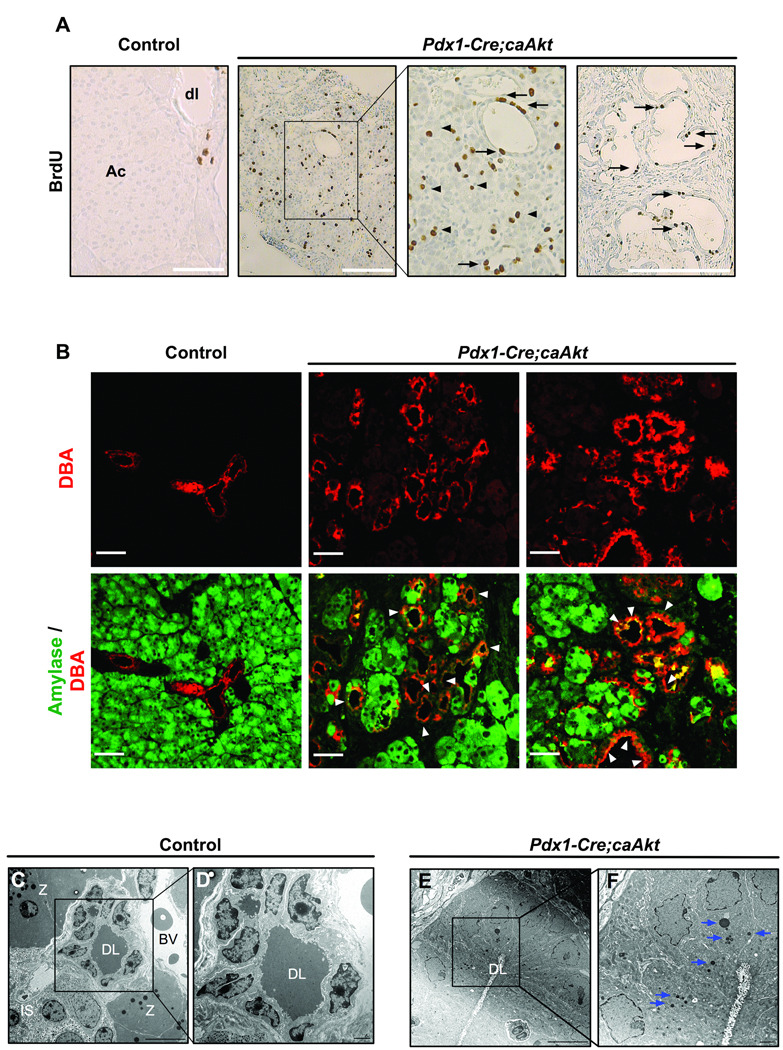

Expansion of the ductal compartment could result from augmented proliferative rate of the ductal epithelium or from transdifferentiation of acinar or β-cells to ductal cells. Assessment of proliferation using BrdU (Figure 4A) or Ki67 (data not shown) showed increased proliferation in ductal and acinar compartment from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata. No evidence of increased apoptosis was observed in ductal or acinar compartments from these animals (data not shown). The contribution of acinar to ductal transdifferentiation was then assessed by the presence of intermediate cells expressing both acinar and ductal markers 26. Confocal analysis of paraffin embedded sections stained for ductal and acinar markers showed co-staining for DBA and amylase in ducts from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice (Figure 4B). Intermediate cells containing zymogen granules were found in ductal structures from the Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreas (Figure 4E, F). While not an absolute proof for transdifferentiation, these studies indicated that acinar to ductal transdifferentiation could contribute to the expansion of EGFP positive ductal structures.

Figure 4. Activation of Akt signaling in Pdx1 cells results in increase proliferation, enlargement of ductal structures with intermediate cells expressing acinar and ductal markers.

(A) BrdU staining in epithelium from ductal structures (arrows) and acinar tissue (arrowheads) in control and Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice. Ac: acinar tissue; dl: ductal lumen. (B) Confocal analysis of immunostaining for DBA (red) and Amylase (green) performed on paraffin sections from 3-month-old mice. Co-localization of amylase and DBA within the ductal structure was observed (arrowheads). (C–F) Electron microscopy from control pancreata and Pdx1-Cre;caAkt. DL: ductal lumen, BV: blood vessel, IS: islet, Z: zymogen granules. Numerous dense zymogen granules were observed in ductal cells of the transgenic animals (arrows). Scale bar, 50 µm (A–B); 10µm (C, E) and 2 µm (D, F).

The studies described above are consistent with a model in which Pdx1 cells over-expressing the caAkt mutant differentiate into acinar and ductal cells and permanent activation of Akt signaling in acinar cells leads to acinar to ductal transdifferentiation. Expression of EGFP in acinar and ductal cells from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice preclude us to show acinar to ductal transdifferentiation by lineage tracing. To test the hypothesis that acinar to ductal transdifferentiation contributes to ductal expansion in this model, we performed lineage-tracing experiments in mice over-expressing caAkt in acinar cells. This was achieved by crossing PCALL2-caAkt mice to animals expressing Cre recombinase driven by the Elastase-1 promoter 19. Crossing Elastase-Cre to the Rosa26R reporter mice demonstrated that Cre expression was specific for the acinar compartment and few β-cells (Figure S3A). Ela-Cre;caAkt animals died around 7 weeks of age from respiratory failure and macroscopic appearance of the pancreas was similar to that of Pdx1-Cre;caAkt (data not shown). Comparable to Pdx1-Cre;caAkt, the acinar architecture of Ela-Cre;caAkt mice was disorganized and exhibited EGFP-expressing acinar cells with heterogeneous amylase staining (Figure 5A). The enlarged cell size of acinar cells made EGFP staining more apparent. Some amylase cells were also observed in ductal structures from the Ela-Cre;caAkt pancreata (Figure 5A). Similar to Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals, five week-old Elastase-Cre;caAkt mice displayed replacement of most of the acinar tissue by EGFP positive ductal structures (Figure 5A). Confocal analysis of Ela-Cre;caAkt pancreata showed expansion of DBA/EGFP positive ductal structures (Figure 5B). In addition to ductal expansion, these structures expressed Pdx1 and Sox9 (Figure S3B and C). These studies demonstrated that Akt activation in acinar cells induces acinar to ductal transdifferentiation, a process that contributes to expansion of the ductal compartment observed in Ela-Cre;caAkt and possibly in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice.

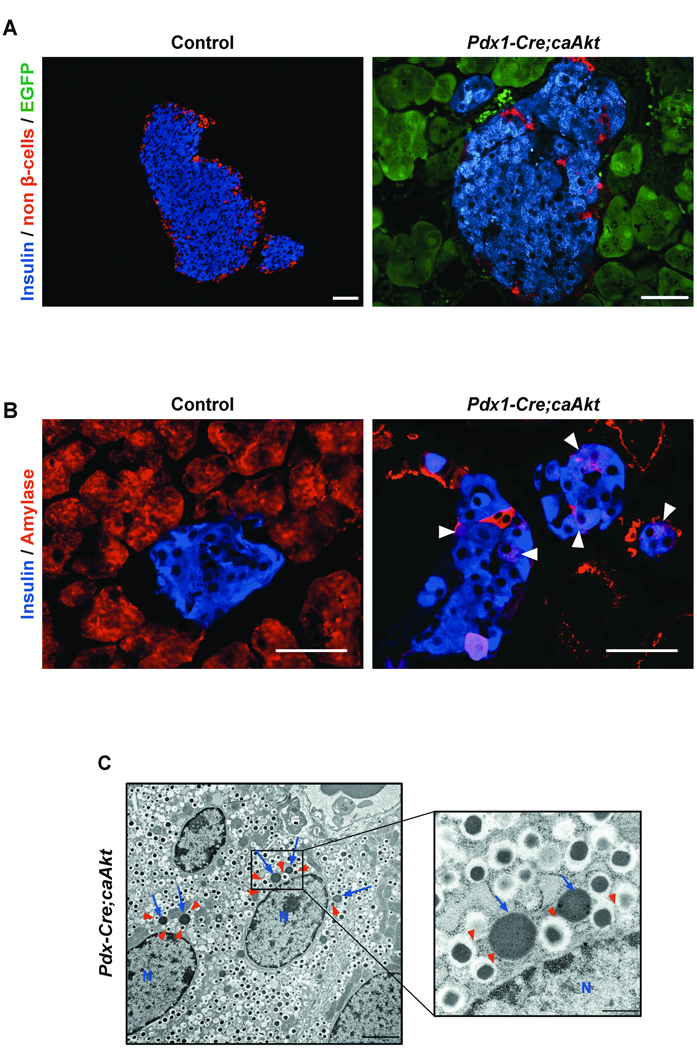

Examination of the β-cell compartment from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt revealed improved glucose tolerance and atypical islets

Assessment of carbohydrate metabolism in 3-month-old mice demonstrated fasting hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemia and improved glucose tolerance in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt transgenics (Figure S4A and B). Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice exhibited a marginal increase in the β-cell area (Figure S4C, p=0.09) and altered islet architecture consisting in abnormal shape and absence of non β-cells in the periphery of the islet (Figure 6A and Figure 3A). Interestingly, these islets contained numerous intermediate cells expressing insulin and amylase suggesting the possibility of p-cell to acinar transdifferentiation (Figure 6B). Consistent with these findings, electron microscopic studies demonstrated β-cells containing both insulin and zymogen granules (Figure 6C). Co-localization of these two types of secretory granules was never observed in controls (Data not shown). These experiments imply that Akt activation in Pdx1 progenitors improves glucose metabolism by increase in insulin levels. The histological analysis was suggestive of p-cell to acinar transdifferentiation.

Figure 6. Islet morphology in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt animals.

(A) Immunostaining for insulin (blue), non β-cells (glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide) (red) and EGFP (green) in 3 month-old mice. (B) Immunostaining for insulin (blue) and amylase (red). Intermediate cells co-expressing insulin and amylase were observed (arrowheads). (C) Electron microscopy of β-cells from 3 month-old mice. β-cells containing numerous zymogen granules (blue arrows) and insulin granules (red arrowheads) were observed. N: nucleus. Scale bar, 50 urn (A, B); 2 µm (C); 500 µm (inset from C).

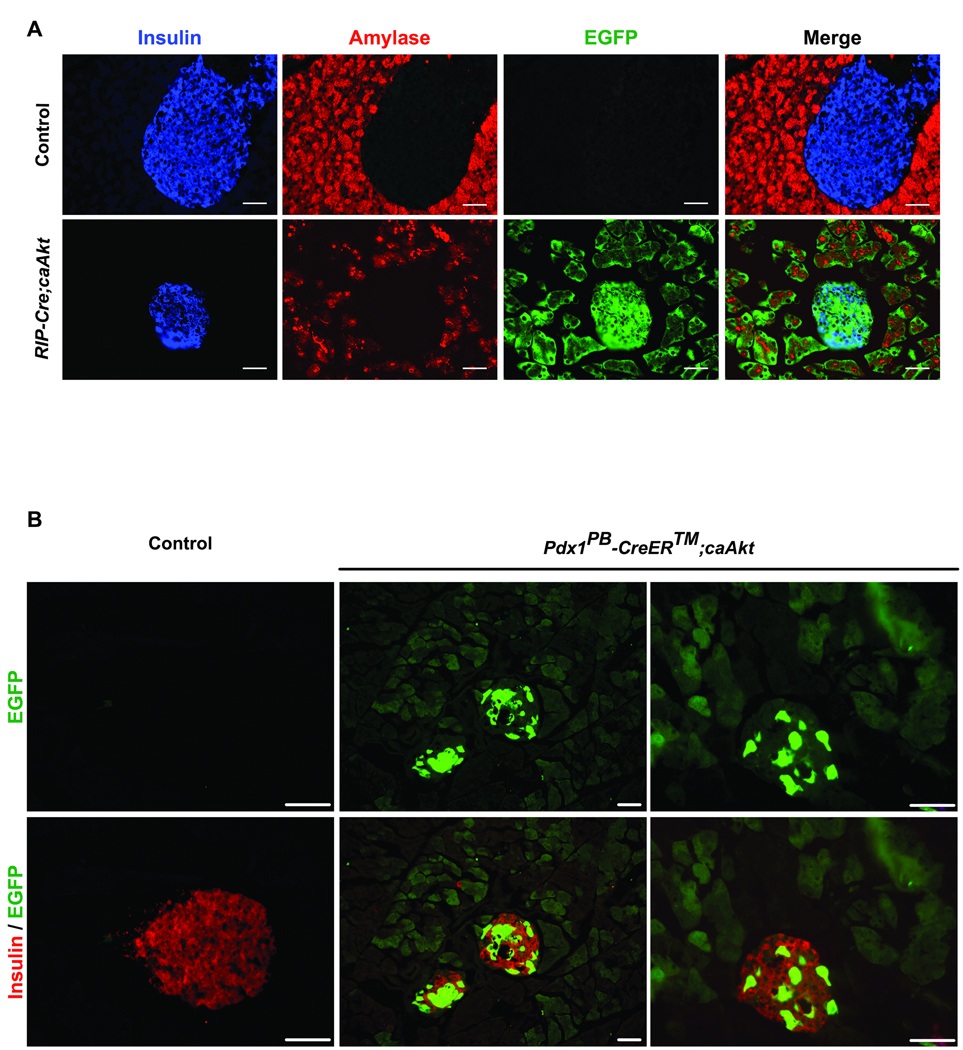

Activation of Akt signaling in β-cells reveals p-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation

Expression of EGFP in acinar cells from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice was a limitation to demonstrate β-cell to acinar transdifferentiation by lineage tracing. The hypothesis that overexpression of Akt in β-cells could induce (3-cell to acinar transdifferentiation was tested in mice overexpressing caAkt in β-cells. This was achieved by crossing PCALL2-caAkt animals with RIP-Cre mice . This transgenic line has been previously shown to induce selective recombination only in β-cells 18. In contrast to control mice, EGFP expression was observed in β-cells from one month-old RIP-Cre;caAkt mice and islet from these mice exhibited intermediate cells expressing both insulin and amylase in some islets (Figure S5A and Figure 7A). Interestingly, EGFP was also detected in the acinar tissue suggesting β-cell to acinar transdifferentiation (Figure 7A). These observations were further confirmed using a specific GFP antibody (Figure S5B and C). GFP positive acinar cells were observed in areas adjacent to islets and in areas devoid of islets (Figure S5C). Further evidence for β-cell to acinar transdifferentiation was obtained by crossing the Pdx1PB CreER™ to PCALL2-caAkt mice 20. Pdx1PB CreER™ mice express a tamoxifen inducible cre mutant under a pancreatic endocrine-specific enhancer (PdxPB). Four-week old Pdx1PB CreER™;caAkt and control mice were injected with tamoxifen. After 8 weeks of tamoxifen injection, Pdx1PB CreER™;caAkt mice displayed EGFP in p-cells and acinar cells confirming our previous observations showing β-cell to acinar transdifferentiation (Figure 7B). Examination of the ductal compartment from RIP-Cre;caAkt mice by DBA staining showed ductal structures expressing EGFP in one and four month-old RIP-Cre;caAkt mice (Figure S6A). These ducts were characterized by elongated epithelial cells occasionally forming a stratified epithelium reminiscent of the abnormalities observed in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt and Ela-Cre;caAkt mice. However, expansion of the ductal compartment was not of the same magnitude. Pdx1 staining in RIP-Cre;caAkt appeared conserved at one and four month-old. (Figure S6B and data not shown). Together, these data demonstrates that activation of Akt in β-cells induces β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation.

Figure 7. Activation of Akt signaling in β-cells induces β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation.

(A) Staining for insulin (blue), amylase (red) with EGFP fluorescence (green) in pancreata from one month-old control and RIP-Cre;caAkt. (B) Staining for insulin (red) with EGFP (green) in control, and Pdx1PB CreER™ ;caAkt pancreata.

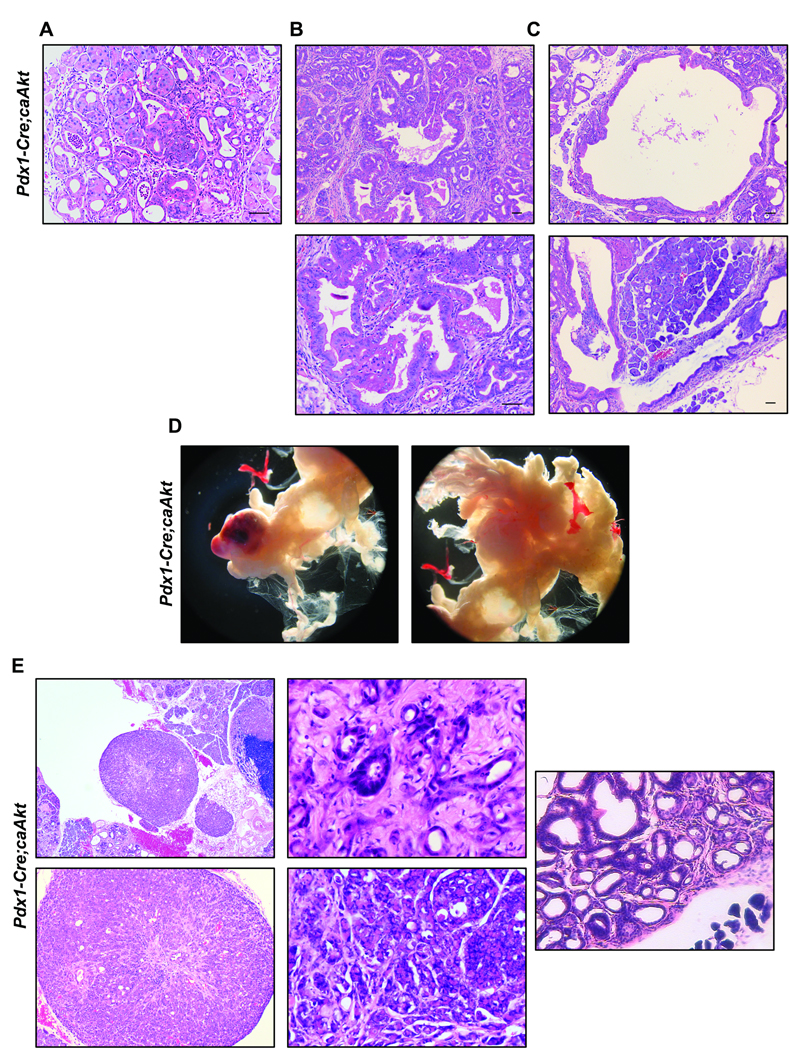

Activation of Akt signaling in pancreatic progenitors results in malignant transformation

To assess the potential role of Akt signaling in malignant transformation of the pancreas we performed a detailed histological analysis. The ductal compartment abnormalities included ductlike structures (not necessarily native ducts) lined by metaplastic cells (Figure 8A). Further analysis showed that these ductal like lesions within the acinar tissue, seemingly arising from the acinar body through the plastic transformation previously discussed (Figure 8B). Consistent with the acinar to ductal metaplastic lesion, pancreatic lysates from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt had increased phosphorylation of Stat3 at Tyr705 when compared to levels found in lysates from control mice (Figure S7A, B) 27. Cytologic atypia and early papillary configuration were also observed in these lesions (Figure 8B). However, these cells did not show full-blown ductal differentiation with abundant intracellular mucin characteristic of mPanINs presumably due to the fact that they arise from either acinar or some stem cells through plasticity (Figure S7C–E). Pancreata from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice also exhibited areas of duct like structures that involved large ducts (Figure 8C). Columnar epithelial cells characterized these lesions with occasional papillary units that resembled intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia (IPMNs) (Figure 8C). To determine whether these pre-malignant lesions transform into carcinoma, we followed a cohort of animals up to 8 months. Five out of five mice developed malignant transformation that consisted in multiple firm pancreatic solid masses (Figure 8D). Multiple cystic structures were also present in pancreata from Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice (Figure 8D). Histological assessment of the tumor revealed diffuse sheets of highly atypical but relatively uniform cells with round nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant chromophilic cytoplasm characteristic of acinar cell carcinoma (Figure 8E). In addition to this classical acinar cell carcinoma, there were rare foci of abortive glandular elements lined by a distinct cell population different than that of the acinar cell carcinoma described above (Figure 8E). These cells were more pleomorphic and had significantly higher nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 8E). The amount, infiltration pattern as well as the cytomorphology of these glandular elements were characteristic of invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. All the components of the tumor expressed EGFP confirming expression of the transgene (data not shown). In addition to the area of acinar carcinoma, focal areas of ductal structures similar to those described in Figure 2A were also observed (Figure 8E). Interestingly, no evidence of true invasiveness or metastatic disease was observed as these mice were sacrificed for assessment of the pancreas morphology and not due to illness.

Figure 8. Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata develop malignant transformation with age.

(A) Histological analysis of three month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt pancreata showing the presence of acinar to ductal metaplasia. Representative areas of ductal lesions involving small ductules (B) and large ducts (C). (D) Pancreas from nine month-old Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice showing a mass and enlarged cystic structures. (E) Histological analysis from the mass shown in panel D illustrating acinar cell carcinomas.

Discussion

The results of these experiments assessed the role of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the differentiation program of the pancreas using a mouse model that provides activation of Akt signaling in a cell type- or developmental stage-specific manner and allow us to perform lineage-tracing analysis. We showed that overexpression of a constitutively active Akt in Pdx1 expressing progenitors, did not inhibit the differentiation program of the pancreas and induced progressive expansion of the ductal compartment. Interestingly, the expanded ductal epithelium showed an increased pool of ductal cells characterized by expression of progenitor markers. The increase in ductal structures observed in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt resulted in part by increased proliferation of the ductal epithelium. A major conclusion derived from the lineage tracing experiments in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt, Elastase-Cre;caAkt, RIP-Cre;caAkt mice was that acinar to ductal and β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation contribute to the expansion of the ductal compartment. The acinar to ductal and (3-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation observed in Ela-Cre;caAkt and RIP-Cre;caAkt mice suggest that the ductal epithelium could be a default fate after activation of Akt signaling in acinar and β-cells. In addition to the changes in cell plasticity, these studies demonstrated that chronic activation of Akt signaling induced the development of pre-malignant lesions and malignant transformation in old mice. In conclusion, the current work demonstrate for the first time that modulation of Akt signaling regulates the fate of differentiated pancreatic cells in vivo and suggests that modulation of Akt signaling could be used as a potential target to generate tissues for regenerative medicine.

The search for adult stem cells in the pancreas has been the major focus of multiple laboratories. The existence of adult stem cells residing in the ductal epithelium, acini and islets has been proposed 28–30. In the current experiments, we showed that activation of Akt signaling in pancreatic progenitors, acinar and β-cells induced expansion of the ductal compartment. Expression of Pdx1, Sox9 and Hes1 in this ductal epithelium is consistent with an expansion of a population that expresses pancreatic progenitor markers. The high level of Sox9 in the ductal epithelium is intriguing as this transcription factor has been shown to be critical for maintaining cells in a stem-like state and inhibiting their differentiation. Moreover, recent data demonstrated that Sox9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor pool 24. In vitro manipulation of this population of ductal cells will provide evidence of the differentiation potential and will establish whether these cells could be considered as progenitors. The expansion of the ductal compartment in these mice was caused at least in part by acinar to ductal and -cell to acinarβ transdifferentiation as suggested by the results of immunostaining and electron microscopy. However, direct proof of acinar to ductal and β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation by lineage tracing in Pdx1-Cre;caAkt mice was technically impossible as EGFP was already expressed in acinar, ductal and β-cells that were derived from Pdx1 cells. Therefore, we performed lineage-tracing experiments in mice with conditional expression of caAkt in acinar or β-cells. Lineage tracing in Elastase-Cre;caAkt mice confirmed that activation of Akt in acinar cells induced acinar to ductal transdifferentiation. Similarly, acinar to ductal transdifferentiation has been reported in mice with overexpression of Pdx1 in acinar cells 27. Knowing that Akt stabilizes Pdx1 levels, it is possible that this mechanism could play a role in acinar to ductal transdifferentiation induced by Akt 31. Interestingly, rapamycin treatment induced reversion of the ductal expansion suggesting that mTOR signaling plays an important role (data not shown). The molecular mechanisms involved in reprogramming mature cells are not completely understood, but these studies suggest for the first time that modulation of Akt signaling could regulate transcription factor networks that control terminally differentiated phenotypes.

Published evidence demonstrated that overexpression of this caAkt mutant driven by the rat Insulin promoter (caAktRIP) exhibited a striking increase in β-cell mass 4, 5. In contrast, RIP-Cre;caAkt exhibited normal glucose tolerance (data not shown) and β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation. The β-cell to acinar transdifferentiation was observed not only when the caAkt mutant was expressed in β-cells during development (Rip-cre;caAkt) but also in mature β-cells from 4 week old mice (Pdx1PB CreERTM;caAkt). These results also demonstrate the plasticity of postnatal mature β-cells. The difference in promoters regulating the Akt mutant could explain the discordant phenotypes between these models. In caAktRIP mice, transcription of the caAkt mutant is abolished during the transdifferentiation process of β-cells to other fates, as the insulin promoter is not longer activated. In contrast, in RIP-Cre;caAkt mice, the p-actin/CMV promoter ensures expression of caAkt during the transdifferentiation process and after β-cells have change to another fate. The continuous transdifferentiation of β-cells to acinar cells in RIP-Cre;caAkt limits the expansion of β-cell mass. Another major finding in RIP-Cre;caAkt was the delayed expansion of the ductal compartment. A plausible explanation for the limited ductal expansion in RIP-Cre;caAkt mice is that β-cells first transdifferentiate to acinar cells and subsequently the constant expression of caAkt turn these cells into ductal cells. These observations indicate that mature pancreatic compartments are not static and multiple fluxes among different fates can occur depending on a particular stimulus.

The experiments in genetically modified mice suggest that activated Ras (KrasG12D) is required for initiation and development of mPanINs lesions 32 and that hedgehog and TGFβ signaling pathways cooperate with Ras in this process 33, 34. Interestingly, Akt signaling seems to be a converging point for activation of Ras and Shh signaling 35. Moreover, amplification of AKT2 in 10%–20% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) lesions provides genetic evidence supporting the importance of this pathway in this type of malignancy 9. The current experiments evaluated the role of the Akt arm of K-Ras signaling in initiation and progression of ductal neoplasias. In these mice, we show that activation of Akt signaling in Pdx1 progenitors results in replacement of the acinar compartment by architectural lesions consisting with acinar to ductal metaplasia, and IPMN. Further characterization of the type of IPMN by staining for Muc1, Muc2, Cdx2 and Muc 5AC was not conclusive. Interestingly, a major difference with the KrasG12D model was the lack of ductal lesions consistent with mPanINs, indicating that signaling pathways different than Akt are involved in development of this premalignant lesion. However, our experiments provide evidence for a crucial role of Akt in cellular plasticity particularly the development of acino-ductal transdifferentiation and IPMN lesions. These observations are consistent with the concept that Akt could mediate the cell plasticity signals induced by activation of K-Ras or other signals. The low penetrance of the tumor phenotype indicates that other rate-limiting events are likely to constrain progression of Pdx1-Cre;caAkt neoplasms toward PDA. Centroacinar cells were found at the same frequency among the groups suggesting that these cells are not major contributors to this phenotype. In contrast to these findings, mice with deletion of PTEN in Pdx1 progenitors exhibited ductal metaplasia that resulted from expansion of centroacinar cells rather than transdifferentiation of acinar cells 12. The absence of transdifferentiation in this model could be explained by the lack of activation of Akt in acinar cells, as PTEN is not expressed in the acinar compartment 12. The rapid progression of metaplastic ductules and development of ductal carcinoma observed in the PTEN mouse model could result from activation of signaling pathways other than Akt. In conclusion, using three different genetic models of lineage tracing (Pdx1-Cre;caAkt, Ela-Cre;caAkt and RIP-Cre;caAkt), the current work provides clear evidence for in vivo acinar to ductal and β-cell to acinar/ductal transdifferentiation as a mechanism for ductal metaplasia and suggests that activation of Akt signaling in acinar and β-cells induces a transdifferentiation program.

This work provides novel insights into the molecular mechanisms that regulate plasticity in terminally differentiated tissues and suggests that modulation of Akt could be a pharmacological target for in vitro manipulation of tissues as replacement therapy. In addition, the current studies shed light on the role of Akt signaling in the pathogenesis of pancreatic carcinoma. The modulation of plasticity and the induction of progenitor markers in the ductal epithelium places Akt as a target for pharmacological therapy to generate tissues as a replacement therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Corrine Lobe for helpful discussion during the generation of transgenic mice and D Melton for providing Pdx1-cre mice. We also thank Timothy Ley, Eleaine Ross, Jacquelin Mudd and Mia Wallace from the Siteman Cancer Center ES Core and Mouse genetic Core. We are grateful to Irina Krits for helpful assistance in the generation of the transgenic mice. We acknowledge the support of the Radioimmunoassay, Morphology and Transgenic core from The Washington University Diabetes Research & Training Center (DRTC). We also thank the Morphology core from Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Core Center (DDRCC) for histology sections. We thank Robert Schmidt and Karen Green for assistance with electron microscopy. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R03 DK068028-01; E. Bernal-Mizrachi). EBM is a recipient of a Career Development Award from the American Diabetes Association.

Abbreviation

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- IPMN

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- mPanINs

mouse pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias

- neoR

neomycin resistance

- PDA

pancreatic ductal carcinoma

- Pdx1

pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1

- Pi3K

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and TENsin homolog

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor β

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests and that all authors approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, et al. Akt1/PKBalpha is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38349–38352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, et al. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta) Science. 2001;292:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garofalo RS, Orena SJ, Rafidi K, et al. Severe diabetes, age-dependent loss of adipose tissue, and mild growth deficiency in mice lacking Akt2/PKB beta. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:197–208. doi: 10.1172/JCI16885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuttle RL, Gill NS, Pugh W, et al. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell growth and survival by the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt1/PKBalpha. Nat Med. 2001;7:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernal-Mizrachi E, Wen W, Stahlhut S, et al. Islet beta cell expression of constitutively active Akt1/PKB alpha induces striking hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1631–1638. doi: 10.1172/JCI13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal-Mizrachi E, Fatrai S, Johnson JD, et al. Defective insulin secretion and increased susceptibility to experimental diabetes are induced by reduced Akt activity in pancreatic islet beta cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:928–936. doi: 10.1172/JCI20016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ptasznik A, Beattie GM, Mally MI, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a negative regulator of cellular differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1127–1136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hori Y, Rulifson IC, Tsai BC, et al. Growth inhibitors promote differentiation of insulin-producing tissue from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16105–16110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252618999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggeri BA, Huang L, Wood M, et al. Amplification and overexpression of the AKT2 oncogene in a subset of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Mol Carcinog. 1998;21:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuveson DA, Hingorani SR. Ductal pancreatic cancer in humans and mice. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:65–72. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thayer SP, di Magliano MP, Heiser PW, et al. Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanger BZ, Stiles B, Lauwers GY, et al. Pten constrains centroacinar cell expansion and malignant transformation in the pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, et al. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, et al. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated excision. Genesis. 2000;28:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elghazi L, Weiss AJ, Gould AP, et al. Generation of a reporter mouse line expressing Akt and EGFP upon Cre-mediated recombination. Genesis. 2008;46:256–264. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129:2447–2457. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrera PL. Adult insulin- and glucagon-producing cells differentiate from two independent cell lineages. Development. 2000;127:2317–2322. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grippo PJ, Nowlin PS, Cassaday RD, et al. Cell-specific transgene expression from a widely transcribed promoter using Cre/lox in mice. Genesis. 2002;32:277–286. doi: 10.1002/gene.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Fujitani Y, Wright CV, et al. Efficient recombination in pancreatic islets by a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-recombinase. Genesis. 2005;42:210–217. doi: 10.1002/gene.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girish V, Vijayalakshmi A. Affordable image analysis using NIH Image/ImageJ. Indian J Cancer. 2004;41:47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi H, Spilde TL, Li Z, et al. Lectin as a marker for staining and purification of embryonic pancreatic epithelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:691–697. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen JN, Cameron E, Garay MV, et al. Recapitulation of elements of embryonic development in adult mouse pancreatic regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:728–741. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seymour PA, Freude KK, Tran MN, et al. From the Cover: SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1865–1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynn FC, Smith SB, Wilson ME, et al. Sox9 coordinates a transcriptional network in pancreatic progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rooman I, Heremans Y, Heimberg H, et al. Modulation of rat pancreatic acinoductal transdifferentiation and expression of PDX-1 in vitro. Diabetologia. 2000;43:907–914. doi: 10.1007/s001250051468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyatsuka T, Kaneto H, Shiraiwa T, et al. Persistent expression of PDX-1 in the pancreas causes acinar-to-ductal metaplasia through Stat3 activation. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1435–1440. doi: 10.1101/gad.1412806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonner-Weir S, Toschi E, Inada A, et al. The pancreatic ductal epithelium serves as a potential pool of progenitor cells. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5(Suppl 2):16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipsett MA, Castellarin ML, Rosenberg L. Acinar plasticity: development of a novel in vitro model to study human acinar-to-duct-to-islet differentiation. Pancreas. 2007;34:452–457. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180335c80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zulewski H, Abraham EJ, Gerlach MJ, et al. Multipotential nestin-positive stem cells isolated from adult pancreatic islets differentiate ex vivo into pancreatic endocrine, exocrine, and hepatic phenotypes. Diabetes. 2001;50:521–533. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boucher MJ, Selander L, Carlsson L, et al. Phosphorylation marks IPF1/PDX1 protein for degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6395–6403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasca di Magliano M, Sekine S, Ermilov A, et al. Hedgehog/Ras interactions regulate early stages of pancreatic cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3161–3173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1470806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, et al. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3147–3160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1475506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rustgi AK. The molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer: clarifying a complex circuitry. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3049–3053. doi: 10.1101/gad.1501106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.