Abstract

We examined the association between five-factor personality domains and facets and spirituality/religiousness as well as their joint association with mental health in a diverse sample of people living with HIV (n = 112, age range 18 – 66). Spirituality/religiousness showed stronger associations with Conscientiousness, Openness, and Agreeableness than with Neuroticism and Extraversion. Both personality traits and spirituality/religiousness were significantly linked to mental health, even after controlling for individual differences in demographic measures and disease status. Personality traits explained unique variance in mental health above spirituality and religiousness. Further, aspects of spirituality and religiousness were found to mediate some of the links between personality and mental health in this patient sample. These findings suggest that underlying personality traits contribute to the beneficial effects of spirituality/religiousness among vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Five-factor model of personality, Spirituality, Religiousness, NEO-PI-R, HIV, AIDS

Introduction

As researchers seek to understand individual differences in people’s psychological resilience to life stressors, both personality traits and spirituality/religiousness (S/R) have emerged as important predictors of sustained well-being in the face of adversity (e.g., Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007; Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Masters & Spielmans, 2007). However, previous studies have examined the mental health benefits of personality traits and S/R independently of each other, and it is not clear how these variables are jointly related to emotional well-being. Also, most research on the relation between personality traits and religiousness has been conducted in healthy, well-adjusted samples (see meta-analysis by Saroglou, 2002) and little is known about their association in vulnerable populations. To address these gaps in the research record, the present study examined the relative association of personality traits and S/R with mental health in a sample of people living with HIV. To provide the background for our predictions, we briefly review previous findings regarding the link between personality and S/R as well as their associations with mental health.

Definitions

In the present paper, we focus on the Five-Factor Model of personality traits (Goldberg, 1993; McCrae & Costa, 2003), a comprehensive and widely replicated trait taxonomy (McCrae et al., 2005; Paunonen, Zeidner, Engvik, Oosterveld, & Maliphant, 2000). It describes personality along the following five dimensions: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. Each of these dimensions is further specified by several individual facets. Gregariousness and Excitement-Seeking, for example, are both facets of Extraversion.

According to Five-Factor Theory (McCrae & Costa, 2003; 2008), personality traits can be understood as basic tendencies that are rooted in biology. As basic traits are channeled through the forces of the surrounding environment, characteristic adaptations, such as attitudes, goals, beliefs, and self-schemas, emerge. Characteristic adaptations, in turn, are thought to interact with external influences and situational factors resulting in an individual’s objective biography which encompasses both overt behavior and emotional reactions. Note that according to Five-Factor Theory, the effects of traits on behaviors and emotional reactions are always mediated by characteristic adaptations.

In contrast to trait psychology, where the Five-Factor Model has emerged as a widely accepted and unifying theoretical framework, research on the psychology of religion relies on a wide variety of measures to capture people’s experience of the sacred. Nevertheless, a basic distinction can be drawn between religiousness and spirituality (e.g., Emmons & Paloutzian, 2003; Hill et al., 2000; Saucier & Skrzypinska, 2006). In broad terms, the concept of religiousness captures adherence to traditional religious creeds, often centered around a specific community of faith (Hill et al.; Saucier & Skrzypinska, 2006). At a more specific level, religiousness encompasses both a specific belief system and a set of behaviors (e.g., prayer, church attendance) associated with these beliefs. Spirituality, in contrast, typically refers to subjective, non-church-centered experiences of the transcendent which imbue everyday life with a sense of deeper meaning (e.g., Emmons, 1999). Some conceptualizations of spirituality also encompass a sense of communion with humanity and compassion for others (e.g., LaPierre, 1994; Elkins, 2001). Although spirituality and religiousness are not mutually exclusive (Hill et al.), there is growing evidence suggesting that they are empirically distinct concepts (Saucier, 2000; Saucier & Skrzypinska, 2006). This differentiation is particularly relevant when studying populations affected by HIV/AIDS who often face stigmatization by institutionalized religion (e.g., Crawford, Allison, Robinson, Hughes, & Samaryk, 1992; Holt, Houg, & Romano, 1999) and may be more likely to describe themselves as spiritual but not religious (Woods & Ironson, 1999).

The association between personality traits and spirituality/religiousness

Since William James and his contemporaries (James, 1902), a long research tradition has linked personality psychology and the psychology of spirituality and religion (for a review see Emmons & Paloutzian, 2003). In recent years, the Five-Factor perspective has emerged as a prominent theoretical framework to inform and guide such inquiries (e.g., Saroglou, 2002; Piedmont, 1999a; Emmons & Paloutzian, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008). Within the framework of Five-Factor Theory (McCrae & Costa, 2003; 2008), religiousness and spiritual seeking would be considered as characteristic adaptations that develop as the expression of basic personality traits is shaped by the surrounding sociocultural context (see Emmons & Paloutzian, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008). This view, which attributes primacy to underlying personality traits, is supported by recent findings suggesting that personality traits in adolescence predict religiousness and spirituality in late adulthood whereas empirical evidence for the converse pattern (i.e., religiousness and spirituality predicting future personality) is scarce (Wink, Ciciolla, Dillon, & Tracy, 2007). Similarly, religious conversion experiences influence characteristic adaptations such as goals and personal attitudes, but have little influence on basic personality traits (Paloutzian, Richardson, & Rambo, 1999).

Consistent with the notion that religiousness and spirituality capture related but distinct aspects of an individual’s relation to the sacred, the two concepts show differential associations to Five-Factor Model personality traits. In a recent meta-analysis, Saroglou (2002) found that religiosity was primarily associated with high Conscientiousness and Agreeableness and, to a lesser extent, to high Extraversion. Spirituality, in turn, showed its strongest association to high Openness, more moderate relations to high Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Extraversion, and a weak association to low Neuroticism. The pattern of associations varies somewhat depending on the specific operationalizations of S/R used in a given study – Saucier and Skrzypinska (2006), for example, did not find a significant association with Conscientiousness –but in general, high Agreeableness appears to show somewhat stronger associations to religiousness than to spirituality, high Openness shows the opposite pattern, high Conscientiousness is related to both concepts, whereas low Neuroticism and high Extraversion show weaker associations to either construct (e.g., Piedmont, 1999b; Leak & Fish, 1999; MacDonald, 2000; Saroglou, 2002; Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008).

Although these findings are intriguing, prior research is limited in several important ways. First, most prior studies have measured personality at the level of the five-factor dimensions and to the best of our knowledge, only three studies have examined facet-level associations (Costa, Busch, Zonderman, & McCrae, 1986; Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008). All of these studies find that some personality facets show stronger associations with S/R than others. However, not a single facet-level association is consistently found across all three studies. Regarding facet-level correlates of religiousness, two of the studies (Costa et al., Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003) agree that religiousness is associated with low scores in impulsiveness, a facet of Neuroticism, low scores in excitement-seeking, a facet of Extraversion, and low scores in openness to values. The two studies that examined facets of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness (Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008) further agree that religiousness is positively associated with the Agreeableness facets straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, and tender-mindedness and the Conscientiousness facet competence. In addition to religiousness, these two studies (Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008) also examined facet-level correlates of spirituality and agree that spirituality is positively associated with openness to fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, and values, the Agreeableness-facet tender-mindedness, and the Conscientiousness-facet competence. However, these findings are limited by the use of a single-item measure of spirituality. Also, for each of the replicated facet-level findings listed above, there are twice as many effects which do not replicate across studies. Clearly, additional research regarding facet-level associations among personality traits and S/R is sorely needed.

Another important concern with prior research is its focus on well-adjusted, healthy, and predominantly Caucasian samples. This constitutes an important gap because ethnic groups tend to differ in their religious orientation and involvement (e.g., Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1994) and such differences may be more salient among populations faced with health-related stressors (Moadel et al., 1999). Also, people’s religious orientation may change when they are faced with severe health problems, such as an HIV diagnosis (e.g., Ironson, Stuetzle, & Fletcher, 2006). Moreover, as we discuss below, both personality traits and S/R have been linked to mental health, an association that carries particular relevance among more vulnerable groups.

Personality traits and spirituality/religiousness are related to mental health

The idea that people with certain personality characteristics are emotionally better off than others has been with us since Hippocratic times. Within the framework of Five-Factor Theory (McCrae & Costa, 2003; 2008), mental health is considered as an aspect of objective biography and thought to be influenced by basic personality traits via the pathway of characteristic adaptations. High scores on the basic traits of Openness and Conscientiousness, for example, may translate into the belief that the world is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful (Feldt, Metsäpelto, Kinnunen, & Pulkkinen, 2007) which in turn promotes better mental health (Antonovsky, 1987).

Consistent with the view that personality characteristics matter for mental health, a meta-analysis examining the association of various personality traits with subjective well-being (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998) found an overall effect size of r = .19, which is larger than the effect sizes for demographic factors or social activities and only outdone by the effect of physical health (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Given that negative emotionality constitutes an important aspect of Neuroticism, it is not surprising that low Neuroticism is commonly found to be the strongest correlate of well-being followed by high Extraversion, high Agreeableness, and high Conscientiousness, whereas Openness shows comparatively smaller, albeit significant associations to well-being (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998).

Religiousness and spirituality have been linked to mental well-being as well. An early meta-analysis examining the association between religiousness and well-being (Witter, Stock, Okun, & Haring, 1985) found an overall effect size of .16 – only slightly lower than that of personality. More recent research supports this pattern and suggests that religious beliefs and behaviors are related to subjective well-being and mental health not only among the general population (Ross, 1990) but also among vulnerable groups dealing with bereavement (McIntosh, Silver, & Wortman, 1993; Sherkat & Reed, 1992) or health problems (Brady, Peterman, Fitchett, Mo, & Cella, 1999; Cotton, Levine, Fitzpatrick, Dold, & Targ, 1999). Although fewer studies have examined the psychological benefits of spirituality, the general pattern of findings is comparable (e.g., Bekelman, Dy, Becker, Wittstein, & Gottlieb, 2007; Seybold & Hill, 2001). In the context of the present research, it is particularly relevant to note several studies which have linked spirituality to better mental health among people living with HIV/AIDS (e.g., Somlai & Heckman, 2000; Simoni & Ortiz, 2003; Braxton, Lang, Sales, Wingood, & DiClemente, 2007).

In summary, Five-Factor Theory predicts that personality traits and S/R are related to each other and that both are important correlates of mental health. Empirical findings generally support this view. However, because prior research has examined the effects of personality and S/R in separate studies, their relative association with beneficial outcomes remains unclear. If one adopts the notion that spirituality and religiousness can be understood as characteristic adaptations based on core personality dimensions, one would expect that any beneficial effects of S/R are at least partially accounted for by the effects of underlying personality traits. The present study was designed to explore this important question.

The present study

As discussed above, previous studies examining the association between personality traits and S/R relied largely on healthy, well-adjusted, and predominantly Caucasian samples. The present study extends these findings by examining a diverse sample of participants faced with the multiple challenges associated with an HIV infection. Conceivably, this choice of sample could influence the observed patterns of effects. For example, HIV positive individuals may turn from organized religion towards a personal sense of spirituality to avoid stigmatization (e.g., Crawford et al., 1992). Also, African American and Hispanic individuals appear to have a greater need for religious involvement than Caucasians (Moadel et al., 1999). However, whereas HIV status and ethnicity are likely to influence mean levels of S/R, the mechanisms by which basic personality traits are translated into characteristic spiritual and religious adaptations should remain the same. We therefore expected to replicate the correlations between personality traits and S/R observed in previous studies.

Specifically, we expected that Conscientiousness would be equally associated with both spirituality and religiousness, Agreeableness would show a relatively stronger association with religiousness than spirituality, Openness would show the opposite pattern, whereas low Neuroticism and high Extraversion would show comparatively weaker associations with S/R. To provide a fine-grained analysis of the link between personality traits and S/R we measured personality both at the level of higher-order factors and at the level of individual facets. We also differentiated among specific aspects of S/R. In general, we expected that the facet-level effects of personality traits would follow the pattern established on the factor level. In addition, we expected to find the specific facet-level associations that were replicated across previous studies (e.g., the link of both religiousness and spirituality with the Agreeableness-facet tender-mindedness or the link of spirituality with Openness to fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, and values).

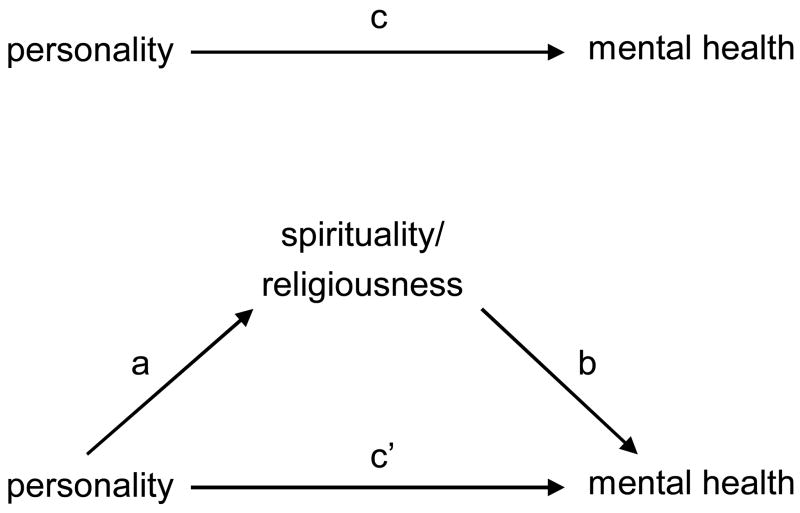

Consistent with prior research, we predicted that both personality traits and S/R would be associated with mental health. Further, based on the theoretical prediction that religiousness and spirituality develop as basic personality traits are channeled by cultural and environmental influences, we expected that underlying personality traits would statistically account for effects of S/R on mental health but not vice versa. We also theorized that individual differences in religiousness and spirituality constitute one of the pathways by which basic personality traits translate into mental health outcomes. Thus we expected, that S/R would partially mediate some of the effects of personality on mental health (see Figure 1 for the proposed mediation model).

Figure 1.

Mediation model

Finally, because personality, S/R, and mental health may also be associated with demographic characteristics, and, in the case of patient samples, with disease status, we included these variables as covariates in all analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were paid volunteers drawn from a larger longitudinal sample (for a detailed description see Ironson et al., 2005) and provided informed consent prior to their participation. Participants were recruited into the parent sample if they were HIV positive and had CD4 counts ranging from 150 to 500. They were excluded if they had ever shown an AIDS defining symptom (Category C). These criteria ensured that participants fell into the mid-range of the disease at the time of recruitment. Additional exclusion criteria included age < 18 years, co-morbidity of other life-threatening illnesses such as cancer, dementia (HIV Dementia Scale; Power, Selnes, Grim, & McArthur, 1995); psychotic or suicidal symptoms, and current drug or alcohol dependence (SCID for DSM-III-R; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, 1987).

The study period for the parent sample ranged from 1997 to 2006. Most of the measures used in the present study were collected during the baseline assessment. Personality assessments were completed at a later date, but in 75% of the cases they were collected within one year of the baseline assessment. Participants were included in the present sample if they had completed valid assessments of personality, S/R, mental health variables, and disease status. Table 1 describes this sample (n = 112) in detail.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Age | 38.1 (8.8), range 18–66 |

| Gender | 67% female |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 35% |

| Caucasian | 31% |

| Hispanic | 27% |

| Other | 7% |

| Education | |

| < 12 years | 19% |

| High school degree | 14% |

| Some college | 36% |

| College degree | 19% |

| Graduate degree | 12% |

| Personality Traits (NEO-PI-R) | |

| Neuroticism | 54.7 (9.9) |

| Extraversion | 50.9 (9.8) |

| Openness | 53.4 (10.4) |

| Agreeableness | 45.0 (10.0) |

| Conscientiousness | 49.0 (10.9) |

| Spirituality/Religiousness (IWSRI) | |

| Spirituality | |

| Sense of Peace | 36.7 (9.5) |

| Compassionate View of Others | 8.8 (1.9) |

| Religiousness | |

| Faith in God | 23.9 (6.9) |

| Religious Behavior | 16.4 (6.1) |

| Emotional Well-Being | |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 10.3 (8.1) |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | 3.9 (3.9) |

| State Anxiety Scale | 39.4 (12.4) |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 17.0 (6.8) |

| Life Orientation Test | 16.4 (4.6) |

| Disease status at baseline | |

| CD4 Count | 360.0 (254.3), range 87 – 2045 |

| Viral load | 33398.6 (87622.9) range 61 – 750,000 |

Note: For continuous measures, SDs are shown in parentheses.

Measures

Demographic covariates included age, gender, ethnicity, and education levels.

Disease status was assessed via CD4 lymphocite count and viral load at baseline (see Ironson et al., 2005, for details regarding the assessment of disease status markers). To account for skewness, viral load was log transformed before inclusion in statistical analyses.

Personality traits were assessed with the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R, Costa & McCrae, 1992) which is based on the Five-Factor Model of Personality (McCrae & Costa, 2003). The 240 items consist of self-descriptive statements and are grouped into five basic personality dimensions – Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness – which are each described along six individual facets. We T-standardized the scores using combined-sex norms and computed factor scores using the scoring weights reported in the manual (Costa & McCrae, 1992). For further information on reliability and validity see the manual (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Spirituality and religiousness were assessed with the short form of the Ironson-Wood Spirituality/Religiousness Index (IWSRI; Ironson et al., 2002) which consists of 25 items grouped into two spirituality scales and two religiousness scales. Among the spirituality scales, “Sense of Peace” (9 items) is characterized by a serene outlook on life and a sense of meaning whereas “Compassionate View of Others” (5 items) assesses tolerance, compassion, and a feeling of connectedness with humanity. Among the religiousness scales, “Faith in God” (6 items) is characterized by a belief in God and his role in aiding recovery from illness whereas “Religious Behavior” (5 items) assesses participation in religious rituals and services. For further information about development of the measure as well as its convergent and discriminant validity see Ironson et al. (2002).

Mental health was captured using a battery of the following measures: The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was used to assess symptoms of depression over the past week; the 20-item Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS, Beck, 1988) was used to assess negative expectations and feelings about the future; the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale examined perceived impact of stress over the past month (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983); the State Anxiety Scale (SA, Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) examined present states of anxiety and worry; and the Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R, Scheier & Carver, 1985) measured optimism.

Results

Personality and Spirituality/Religiousness

Table 2 reports partial correlations between personality factors and facets and the subscales of the IWSRI controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, education, CD4 count, and viral load. Among the personality factors, Conscientiousness showed the most consistent pattern of associations to S/R with significant partial correlations to all of the IWSRI subscales. This pattern was echoed on the facet level where 23 of 24 possible correlations between Conscientiousness-facets and IWSRI subscales reached statistical significance. This indicates that people who are organized and deliberate and approach life’s challenges with confidence and discipline show higher levels of both spirituality and religiousness. Among the subscales, the strongest association with Conscientiousness was found for Sense of Peace indicating that an organized and self-disciplined approach to life contributes to a serene outlook and a sense of meaning. The next strongest association with Conscientiousness was found for Faith in God, indicating that individuals high in Conscientiousness believe in God and ascribe him an important role in their recovery. Somewhat weaker correlations suggested that conscientious individuals also have a Compassionate View of Others and engage in more Religious Behavior.

Table 2.

Partial correlations of personality factors and facets with spirituality/religiousness controlling for demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, and education) and disease status (CD4 Count and log of viral load)

| IWSRI Spirituality Scales | IWSRI Religiousness Scales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of Peace | Compassion | Faith in God | Religious Behavior | |

| N: Neuroticism | −.16 | −.01 | −.06 | −.29** |

| E: Extraversion | .06 | .07 | .05 | .12 |

| O: Openness | .28** | .35** | .30** | .11 |

| A: Agreeableness | .19* | .13 | .31** | .25* |

| C: Conscientiousness | .45** | .37** | .41** | .31** |

| N1: Anxiety | −.21* | −.08 | −.09 | −.20* |

| N2: Angry Hostility | −.20* | −.10 | −.24* | −.22* |

| N3: Depression | −.28** | −.18 | −.19 | −.27** |

| N4: Self-Consciousness | −.15 | −.14 | −.05 | −.13 |

| N5: Impulsiveness | −.27** | −.10 | −.26** | −.39** |

| N6: Vulnerability | −.27** | −.16 | −.23* | −.32** |

| E1: Warmth | .15 | .15 | .20* | .23* |

| E2: Gregariousness | .08 | .02 | .07 | .23* |

| E3: Assertiveness | .15 | .11 | .11 | .23* |

| E4: Activity | .15 | .15 | .07 | .01 |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | .01 | −.01 | .02 | .10 |

| E6: Positive Emotions | .26** | .26** | .22* | .29** |

| O1: Fantasy | .16 | .21* | .17 | −.02 |

| O2: Aesthetics | .26** | .30** | .33** | .15 |

| O3: Feelings | .10 | .22* | .12 | −.09 |

| O4: Actions | .04 | .06 | .06 | .02 |

| O5: Ideas | .33** | .39** | .30** | .22* |

| O6: Values | −.02 | .03 | −.01 | −.14 |

| A1: Trust | .21* | .08 | .16 | .32** |

| A2: Straightforwardness | .09 | .03 | .19 | .10 |

| A3: Altruism | .20* | .20* | .24* | .18 |

| A4: Compliance | .26** | .08 | .24* | .33** |

| A5: Modesty | −.09 | −.05 | .06 | −.06 |

| A6: Tender-Mindedness | .23* | .26** | .33** | .17 |

| C1: Competence | .39** | .31** | .31** | .34** |

| C2: Order | .36** | .26** | .32** | .16 |

| C3: Dutifulness | .34** | .24* | .34** | .36** |

| C4: Achievement Striving | .35** | .30** | .31** | .24* |

| C5: Self-Discipline | .38** | .23* | .32** | .30** |

| C6: Deliberation | .35** | .33** | .35** | .34** |

Note: p < .05;

p < .01

The next strongest associations between personality traits and IWSRI were seen for Agreeableness and Openness. On the factor level, both of them were significantly associated with three of the IWSRI subscales. Consistent with prior research, Agreeableness was associated with both of the religiosity subscales, but also showed a somewhat weaker relation to one of the spirituality subscales, Sense of Peace. Facet level findings suggested that A3: Altruism, A4: Compliance, and A6: Tender-Mindedness were each linked to three of the IWSRI subscales and A1: Trust was linked to two subscales, whereas A2: Straightforwardness and A5: Modesty were not significantly related to S/R.

On the factor level, Openness was associated with both of the spirituality factors as well as one of the religiousness scales: Faith in God. An examination of facet level associations revealed a more differentiated pattern suggesting that the associations of Openness with IWSRI scores were primarily driven by the facets O2: Aesthetics and O5: Ideas. This indicates that people who show a greater appreciation of beauty and intellectual curiosity are more likely to report a Sense of Peace, Faith in God, and a Compassionate View of Others. In contrast, Openness showed little relation to Religious Behavior.

For Neuroticism, significant associations on the factor-level were limited to the Religious Behavior scale indicating that individuals who are prone to experience negative affect and worry are less likely to engage religious activities. On the facet level, facets of Neuroticism showed associations to three of the IWSRI scales. Specifically, individuals who are angry and hostile (N2), have difficulty controlling their impulses (N5), and feel vulnerable (N6) show lower Sense of Peace, Faith in God, and Religious Behavior. Further, people who are prone to experience anxiety (N1) and depressive affect (N3) feel less at peace and are less likely to engage in religious behavior.

Among the five personality dimensions, Extraversion was the only one that showed no factor-level associations to IWSRI scores. On the facet level, a tendency to experience positive emotions (E6) was associated with higher scores on all of the IWSRI subscales. Religious Behavior was also linked to interpersonal warmth (E1), gregariousness (E2), and a tendency to take on social leadership (E3) whereas Faith in God was only linked to E1: Warmth.

To sum up, correlational analyses revealed moderate correlations between personality traits and S/R at both the factor and the facet level with the strongest associations found for Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Openness and only sporadic associations for Neuroticism and Extraversion.

Personality traits, spirituality/religiousness, and mental health

In a next step, we attempted to replicate previous research findings indicating that both personality and S/R are associated with levels of mental health. To this end, the left columns of Table 3 report partial correlations between personality factors, IWSRI scores and measures of mental health while controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, education, CD4 count, and viral load.1

Table 3.

Partial correlations of personality factors and spirituality/religiousness with mental health controlling for demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, and education) and disease status (CD4 Count and log of viral load)

| BDI | BHS | State Anxiety | Perceived Stress Scale | Life Orientation Test | Mental Health Aggregate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEO-PI-R | ||||||

| N: Neuroticism | .24* | .28** | .37** | .43** | −.44** | −.43** |

| E: Extraversion | −.20* | −.26** | −.12 | .01 | .18 | .19 |

| O: Openness | −.21* | −.32** | −.25* | −.08 | .25** | .28** |

| A: Agreeableness | −.13 | −.26** | −.09 | −.15 | .28** | .23* |

| C: Conscientiousness | −.27** | −.44** | −.29** | −.20* | .33** | .38** |

| IWSRI Spirituality | ||||||

| Sense of Peace | −.27** | −.42** | −.35** | −.35** | .44** | .45** |

| Compassion | −.18 | −.28** | −.27** | −.25* | .26** | .31** |

| IWSRI Religiousness | ||||||

| Faith in God | −.23* | −.44** | −.24* | −.27** | .36** | .38** |

| Religious Behavior | −.14 | −.30** | −.27** | −.37** | .29** | .34** |

Note: BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale;

p < .05;

p < .01

Consistent with prior research, both personality factors and IWSRI scores were significantly associated with mental health after controlling for demographic variables and indicators of disease status. The general pattern of correlations was consistent across different aspects of mental health and suggested that Neuroticism was associated with lower levels of mental health (i.e., higher levels of depression, hopelessness, anxiety and stress as well as lower levels of optimism). The remaining personality factors as well as the IWSRI subscales were positively associated with mental health. Among the mental health variables, this pattern was strongest for hopelessness and optimism and somewhat weaker for depression, state anxiety, and perceived stress. Among the personality factors, Neuroticism and C showed the strongest association with mental health variables and among the IWSRI subscales Sense of Peace and Faith in God showed the strongest and most consistent links to mental health.2

Because the pattern of correlations was relatively consistent across mental health indicators, we computed a mental health aggregate score for use in subsequent analyses. This approach was supported by the results of a principal components analysis applied to the range of mental health variables. Both the Scree plot and the Eigenvalue criterion strongly suggested a one-component solution with the first component accounting for 65% of the variance. To compute the aggregate mental health score, we reversed the scores for BDI, BHS, State Anxiety, and Perceived Stress Scale such that higher scores indicated better mental health. We then z-standardized the individual scales and computed the mean across scales for each participant. The partial correlations of the mental health aggregate score with personality traits and S/R are reported in the right column of Table 3.

The results reported so far indicate that Neuroticism, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness are significantly associated with certain aspects of religiousness and spirituality. In addition, both personality traits and aspects of S/R are significantly associated with mental health, even after controlling for demographic variables and indicators of disease status in this diverse patient sample. To examine the relative contributions of personality and S/R to mental health, we computed two hierarchical linear regressions examining the unique variance in the aggregate mental health score accounted for by personality and IWSRI scores. Both analyses controlled for demographic variables and disease status in a first block. The second and third blocks differed across analyses. In the first analysis, we entered personality variables in the second block and IWSRI scores in the third block. The reverse sequence was used in the second analysis. Table 4 summarizes the results of the two analyses. Findings indicate that the sum of predictors in each of the analyses accounted for 44% of the variance in mental health (R2= .44, p < .001). In the first analysis, where personality factors were entered before S/R, they accounted for 35% of the variance in mental health scores. Adding IWSRI scores in a third block did not increase the explained variance by a significant amount. In contrast, when IWSRI scores were entered before personality they accounted for only 21% of the variance in mental health. Moreover, when personality factors were entered in a subsequent block they added significantly (by 19%) to the explained variance. These findings suggest that in this patient sample, personality traits were more strongly associated with mental health than S/R scores and accounted for a unique portion of the variance that did not overlap with S/R.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear regression analyses examining the percentage of variance accounted for by personality traits versus spirituality/religiousness

| ΔR2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Personality entered before S/R | S/R entered before Personality | |

| Block 1: Control variables | .04 | .04 |

| Block 2 | .35** | .21** |

| Block 3 | .05 | .19** |

Note: p < .05;

p < .01

Mediation analyses

To shed further light on the complex association between personality, S/R, and mental health, we conducted mediation analyses in which we examined whether aspects of S/R acted as mediators of the effects of personality traits on mental health. Figure 1 shows a schematic of the mediation models tested. The correlational analyses reported above suggest that personality traits show differential relations to specific aspects of S/R. We therefore conducted analyses at the level of the five personality traits and individual IWSRI subscales. Analyses were limited to those combinations of five-factor traits and S/R scales that showed significant correlations (see Table 2) and thus met a basic pre-requisite for mediation.

Following the guidelines by Baron and Kenny (1986) we conducted a series of regression analyses to test the different paths of the model shown in Figure 1. Each of the regressions controlled for demographic variables and disease status. Table 5 summarizes the results of each step towards establishing mediation. Step 1 estimated the c paths by regressing the mental health aggregate variable based on the personality factors. Step 2 estimated the a paths by regressing each of the IWSRI subscales based on the personality factors. Step 3 estimated the b paths by regressing the mental health aggregate variable based on each of the IWSRI subscales while including the personality traits as predictors in the same equation. Step 4 estimated the c′ paths and differentiated between partial and complete mediation by examining whether or not the effects of the personality traits on the mental aggregate variables were reduced to zero when IWSRI scores were included as predictors in the same equation. Note that steps 3 and 4 were tested in the same regression equation. Finally, to examine the significance of the indirect effects (c-c′) we conducted Sobel tests (Sobel, 1982; McKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Table 5.

Summary of mediation analyses examining indirect effects of personality traits on mental health aggregate scores mediated by IWSRI subscores.

| Predictor | Mediator | Step 1 Path c | Step 2 Path a | Step 3 Path b | Step 4 Path c′ | Sobel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ||||||

| Rel. Behavior | −.036(.007)** | −.152(.053)** | .033(.013)* | −.031(.007)* | −1.90 | |

| O | ||||||

| Sense of Peace | .021(.008)* | .276(.093)** | .035(.008)** | .011(.008) | 2.46** | |

| Compassion | .021(.008)* | .064(.018)** | .111(.043)* | .014(.008) | 2.09* | |

| Faith in God | .021(.008)* | .192(.063)** | .042(.012)** | .013(.008) | 2.30* | |

| A | ||||||

| Sense of Peace | .020(.008)* | .171(.091) | .035(.007)** | .014(.007) | 1.76 | |

| Faith in God | .020(.008)* | .194(.060)** | .042(.012)** | .012(.008) | 2.37* | |

| Rel. Behavior | .020(.008)* | .134(.053)* | .042(.014)** | .014(.008) | 1.93 | |

| C | ||||||

| Sense of Peace | .028(.007)** | .404(.078)** | .030(.008)** | .016(.007)* | 3.04** | |

| Compassion | .028(.007)** | .065(.016)** | .084(.042)* | .023(.007)** | 1.79 | |

| Faith in God | .028(.007)** | .248(.054)** | .034(.012)** | .020(.007)** | 2.41* | |

| Rel. Behavior | .028(.007)** | .163(.049)** | .035(.013)* | .023(.007)** | 2.09* | |

Note: Rel. Behavior = Religious Behavior. Table shows unstandardized regression coefficients. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

As seen in Table 5, the effect of Openness on the mental health aggregate was mediated by Sense of Peace, Compassion, and Faith in God. Further, the effect of Agreeableness on the mental health aggregate was mediated by Faith in God. Finally, the effect of Conscientiousness on the mental health aggregate was partially mediated by Sense of Peace, Faith in God, and Religious Behavior.3,4

Discussion

The present study adds in several important ways to our understanding of the association between personality traits and S/R and their joint association with mental health. For one, we examined the link between personality and S/R in a diverse sample of patients dealing with a severe health problem. Our results are reassuringly consistent with previous studies that were conducted in predominantly healthy and White samples: Conscientiousness was positively associated with all spirituality and religiousness scales, Openness showed positive associations with both spirituality scales but only one of the religiousness scales, and the reverse was true for Agreeableness. Also consistent with previous findings, Neuroticism and Extraversion showed relatively little association with S/R. This suggests that the general pattern of associations between personality traits and S/R holds true across diverse samples.

Our findings also add to the scarce literature examining facet-level associations between personality and S/R. Most of the facet-level associations that were replicated across at least two of the previous studies are found in the present study as well. Thus, evidence is mounting that religiousness is associated with low scores on the Neuroticism-facet N5: Impulsiveness and high scores on the Agreeableness-facets A3: Altruism and A4: Compliance. Also, consistently across studies, aspects of spirituality were associated with high scores on the Openness-facets O1: Fantasy, O2: Aesthetics, and O3: Feelings. Further, consistent with previous studies, high scores on the Agreeableness-facet A6: Tender-Mindedness and the Conscientiousness-facet C1: Competence were associated with both spirituality and religiousness. Based on these correlates, both religious and spiritual individuals feel in charge of their lives and show high levels of sympathy and concern for others. In addition, primarily religious individuals are uniquely characterized by the ability to resist temptations coupled with the tendency to de-escalate social conflicts and assist others in need. Primarily spiritual individuals, in turn, show vivid imagination, appreciation for beauty, and receptiveness to their inner feelings.

Given that the previous studies on facet-level associations (Costa, Busch, Zonderman, & McCrae, 1986; Saroglou & Fiasse, 2003; Saroglou & Munoz-Garcia, 2008) were conducted in three different countries and languages (U.S., Belgium, and Spain, respectively) it is not too surprising that we also found some significant facet-level correlates that were not found in previous studies and failed to find other facet-level associations that were previously reported. Perhaps the most surprising finding is that we did not replicate previous results linking Openness to Values (O6) to low religiousness and high spirituality. One possible explanation is that these discrepancies are due to differences in measures. In previous studies, the strongest negative association between O6 and religiousness was found by Costa et al. (1986) who used a MMPI-derived religiousness indicator that emphasized religious fundamentalism. The IWSRI religiousness scales, in contrast, do not include a fundamentalist element. Another surprising finding was that the Compassionate View of Others scale was significantly associated with Openness and Conscientiousness but not with Agreeableness. Note, however, that at the facet level both A3: Altruism and A6: Tender-mindedness were linked to compassion. The association of compassion with Openness and Conscientiousness, in turn, may be explained by the wording of the IWSRI items which emphasize tolerance as well as a sense of duty and responsibility towards others. Similarly, associations between Religious Behavior and facets of Extraversion may be influenced by the fact that IWSRI items emphasize religious activities with a social component

The present findings also add to our understanding of the joint association of personality traits and S/R with mental health. Correlational analyses replicated previous findings and indicate that both S/R and personality traits are important correlates of mental health in this patient sample. Importantly, our findings suggest that when the five NEO-PI-R domains are considered in combination, underlying personality traits fully account for the association of S/R with mental health. This is consistent with the theoretical claim that religiousness and spirituality are characteristic adaptations that develop as basic personality traits are channeled by cultural and environmental influences. Furthermore, a set of mediation analyses provide good initial evidence that certain aspects of S/R mediate the relationship of both Openness and Agreeableness with mental health. In contrast, the results for Conscientiousness suggest only partial mediation, and the association of Neuroticism and Extraversion with mental health does not show evidence of mediation via S/R. This is consistent with our finding that, when taken together, five-factor traits as measured by the NEO-PI-R add significantly to the explained variance in mental health even if variance due to S/R has been accounted for.

In interpreting our findings, several important limitations of the present study need to be acknowledged. For one, our analyses are correlational and although they are consistent with the causal model proposed by Five-Factor Theory (McCrae & Costa, 2008), longitudinal studies are needed to establish the direction of causality. Also, although our sample was diverse in terms of ethnic background and educational status, all participants were dealing with very similar health concerns (i.e., HIV). Future studies need to examine if our results translate to different patient and non-patient populations. Another important limitation of the present study is that measures of S/R and psychosocial well-being were not collected concurrently with personality assessments. Given that three quarters of the NEO-PI-R assessments were collected within one year of the other measures and personality remains largely stable in adulthood (Roberts & Del Vecchio, 2000) the time gap should have had a minor influence on the present findings. Nevertheless, this issue needs to be addressed in future research.

In spite of these limitations, the present study makes important contributions to our understanding of the link between personality traits and S/R. In addition to their theoretical relevance, our findings also have important practical implications because the mediation analyses suggest that the benefits of S/R for mental health are largely dependent on a person’s underlying personality traits. This implies that any interventions aimed at inducing a turn towards religion in order to improve mental health may be misguided. Instead, medical professionals may want to assess their clients’ personality profile to determine who may benefit most from access to spiritual and/or religious support and guidance.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Grants R01MH53791 and R01MH066697 (to G.I.) from the National Institutes of Health and supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. Paul T. Costa, Jr. receives royalties from the NEO-PI-R.

Footnotes

Note that Ironson et al. (2002) reported associations between IWSRI scores and aspects of mental health in a partially overlapping sample. We report some related correlations in the bottom rows of Table 3 because they provide the necessary background for subsequent (and entirely novel) analyses examining the relative contributions of personality traits and S/R to mental health.

Supplemental analyses examined partial correlations of disease status with personality traits and IWSRI scores (controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, and education). For personality traits, we found a weak association between Neuroticism and more favorable CD4 counts (r = .20, p = .04), but no such association was found for viral load. Also, there were no significant associations between IWSRI scores and indicators of disease status. Subsequent analyses therefore focused on mental health as an outcome variable.

In recent years, alternative methods for testing indirect effects have been proposed. The most prominent among these approaches involves bootstrapping (e.g., Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Using an SPSS macro by Preacher & Hayes (2008), we repeated our analyses using 5000 bootstrap resamples and including the same demographic and diseases status covariates as above. The results replicate all of the significant mediation effects reported in Table 5. In addition, the mediation effects for N via Religious Behavior, and A via Sense of Peace and Religious Behavior reached significance as well. However, given the large number of mediation analyses conducted in the present study, we opted to focus our discussion on the more conservative Sobel test results.

In supplemental analyses we regressed aggregate mental health on control variables, mean-centered personality and IWSRI scores, and personality by IWSRI interactions. None of the interaction terms added significantly to the explained variance.

References

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Beck Hopelessness Scale. The Psychological Corporation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bekelman D, Dy SM, Becker D, Wittstein I, Gottlieb S. Spiritual well-being and depression in patients with heart failure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:440–447. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braxton N, Lang DL, Sales JM, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The role of spirituality in sustaining the psychological well-being of HIV-positive Black women. Women’s Health. 2007;46:113–129. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Flachsbart C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:1080–1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Busch CM, Zonderman AB, McCrae RR. Correlations of MMPI factor scales with measures of the five factor model of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1986;50:640–650. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5004_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, Dold KH, Targ E. Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being, quality of life, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:429–438. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<429::aid-pon420>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Allison KW, Robinson WL, Hughes D, Samaryk M. Attitudes of African American Baptist ministers towards AIDS. Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:304–308. [Google Scholar]

- DeNeve KM, Cooper H. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:197–229. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins DN. Beyond religion: Toward a humanistic spirituality. In: Schneider KJ, Bugental JFT, Pierson JF, editors. The handbook of humanistic psychology. London: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Paloutzian RF. The psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:377–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldt T, Metsäpelto RL, Kinnunen U, Pulkkinen L. Sense of coherence and five-factor approach to personality: Conceptual relationships. European Psychologist. 2007;12:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI, Wood RW, Jr, McCullough ME, Swyers JP, Larson DB, et al. Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal of Theory of Social Behavior. 2000;30:51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Holt JL, Houg BL, Romano JL. Spiritual wellness for clients with HIV/AIDS: Review of counseling issues. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1999;77:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, O’Cleirigh C, George A, Kumar M, et al. The Ironson-Woods spirituality/religiousness index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:34–38. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, O’Cleireigh C, Fletcher M, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Klimas N, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S62–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. Plain label books. 1902. The varieties of religious experiences. Books.google.com. [Google Scholar]

- LaPierre L. A model for describing spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health. 1994;33:153–161. doi: 10.1007/BF02354535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak GK, Fish SB. Development and initial validation of a measure of religious maturity. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 1999;9:83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49:137–145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald DA. Spirituality: Description, measurement, and relation to the five factor model of personality. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:149–197. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.t01-1-00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test the significance of the mediated effect. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters KS, Spielmans GI. Prayer and health: Review, meta-analysis, and research agenda. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . Personality in adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory perspective. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . The Five-Factor Theory of personality. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 3. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Terracciano A 78 Members of the Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:547–561. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DN, Silver RC, Wortman CB. Religion’s role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:812–821. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, Grennan J, Carter J, LaRuffa G, Skummy A, Dutcher J. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:378–385. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, Richardson JT, Rambo LR. Religious conversion and personality change. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:1047–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Paunonen SV, Zeidner M, Engvik HA, Oosterveld P, Maliphant R. The nonverbal assessment of personality in five cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2000;31:220–239. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL. Strategies for using the five-factor model of personality in religious research. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1999a;27:338–350. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL. Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality. 1999b;67:985–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV Dementia Scale: a rapid screening test. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1995;8:273–278. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Del Vecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Religion and psychological distress. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990;29:236–45. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou V. Religion and the five factors of personality: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou V, Fiasse L. Birth order, personality, and religion: A study among young adults from a three-sibling family. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou V, Muñoz-García A. Individual differences in religion and spirituality: An issue of personality traits and/or values. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2008;47:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G. Isms and the structure of social attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:366–385. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G, Skrzypinska K. Spiritual but not religious? Evidence for two independent dispositions. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1257–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seybold KS, Hill PC. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE, Reed MD. The effects of religion and social support on self-esteem and depression among the suddenly bereaved. Social Indicators Research. 1992;26:259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Ortiz MZ. Mediational models of spirituality and depressive symptomatology among HIV-positive Puerto Rican women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:3–15. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Somlai AM, Heckman TG. Correlates of spirituality and well-being in a community sample of people living with HIV disease. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture. 2000;3:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RC, Lushene RE. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M. Instruction manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wink P, Ciciolla L, Dillon M, Tracy A. Religiousness, Spiritual Seeking, and Personality: Findings from a Longitudinal Study. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:1051–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter RA, Stock WA, Okun MA, Haring MJ. Religion and subjective well-being in adulthood: A quantitative synthesis. Review of Religious Research. 1985;26:332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Woods TE, Ironson GH. Religion and spirituality in the face of illness: How cancer, cardiac, and HIV patients describe their spirituality/religiosity. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:393–412. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]