Abstract

Objective

To review maternal deaths and the dose-related effects of misoprostol on blood loss and pyrexia in randomized trials of misoprostol use for the prevention or treatment of postpartum haemorrhage.

Methods

We searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and Pubmed, without language restrictions, for “(misoprostol AND postpartum) OR (misoprostol AND haemorrhage) OR (misoprostol AND hemorrhage)”, and we evaluated reports identified through the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group search strategy. Randomized trials comparing misoprostol with either placebo or another uterotonic to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage were checked for eligibility. Data were extracted, tabulated and analysed with Reviewer Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software.

Findings

We included 46 trials with more than 40 000 participants in the final analysis. Of 11 deaths reported in 5 trials, 8 occurred in women receiving ≥ 600 µg of misoprostol (Peto odds ratio, OR: 2.49; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.76–8.13). Severe morbidity, defined as the need for major surgery, admission to intensive care, organ failure or body temperature ≥ 40 °C, was relatively infrequent. In prevention trials, severe morbidity was experienced by 16 of 10 281 women on misoprostol and by 16 of 10 292 women on conventional uterotonics; in treatment trials, it was experienced by 1 of 32 women on misoprostol and by 1 of 32 women on conventional uterotonics. Misoprostol recipients experienced more adverse events than placebo recipients: 8 of 2070 versus 5 of 2032, respectively, in prevention trials, and 5 of 196 versus 2 of 202, respectively, in treatment trials. Meta-analysis of direct and adjusted indirect comparisons of the results of randomized trials showed no evidence that 600 µg are more effective than 400 µg for preventing blood loss ≥ 1000 ml (relative risk, RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.71–1.48). Pyrexia was more than twice as common among women who received ≥□600 µg rather than 400 µg of misoprostol (RR: 2.53; 95% CI: 1.78–3.60).

Conclusion

Further research is needed to more accurately assess the potential beneficial and harmful effects of misoprostol and to determine the smallest dose that is effective and safe. In this review, 400 µg of misoprostol were found to be safer than ≥ 600 µg and just as effective.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la mortalité maternelle et les effets dose-dépendants du misoprostol sur la perte de sang et la pyrexie dans le cadre d’essais randomisés portant sur l’utilisation de ce médicament pour prévenir et traiter les hémorragies postpartum.

Méthodes

Nous avons fait des recherches dans le registre Cochrane des essais contrôlés et dans Pubmed sans émettre de restriction concernant la langue et en utilisant l’expression «(misoprostol AND postpartum)» OR (misoprostol AND haemorrhage) OR (misoprostol AND hemorrhage), puis nous avons évalué les rapports identifiés avec la stratégie de recherche du Groupe Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. Nous avons vérifié la conformité avec les critères d’admissibilité dans l’étude des essais randomisés comparant le misoprostol à un placebo ou à un autre utérotonique dans la prévention ou le traitement des hémorragies postpartum. Nous avons extrait et tabulé des données, puis nous les avons analysées avec le logiciel Reviewer Manager (RevMan) 4.3.

Résultats

Dans l’analyse finale, nous avons pris en compte 46 essais portant sur plus de 40 000 participantes. Sur 11 décès rapportés dans 5 essais, 8 sont survenus chez des femmes ayant reçu ≥ 600 µg de misoprostol (Odds ratio de Peto, OR : 2,49 ; intervalle de confiance à 95 %, IC : 0,76-8,13). La morbidité grave, définie comme la nécessité d’une intervention chirurgicale importante, l’admission en soins intensifs, la défaillance d’un organe ou une température corporelle ≥ 40 °C, était relativement rare. Dans les essais de prévention, nous avons relevé une morbidité grave chez 16 des 10281 femmes sous misoprostol et chez 16 des 10292 parturientes recevant un utérotonique classique et, dans les essais thérapeutiques, chez une des 32 femmes sous misoprostol et chez une des 32 femmes sous utérotonique classique. Les femmes recevant du misoprostol ont manifesté plus d’effets indésirables que celles recevant un placebo : 8 sur 2070 contre 5 sur 2032 respectivement dans les essais de prévention et 5 sur 196 contre 2 sur 202 dans les essais thérapeutiques. La méta-analyse des comparaisons directes et indirectes ajustées des résultats d’essais randomisés n’a fait apparaître aucune preuve d’une efficacité supérieure de la dose de 600 µg de misoprostol par rapport à la dose de 400 µg, dans la prévention d’une perte de sang ≥ 1000 ml (risque relatif, RR : 1,02 ; IC à 95 % : 0,71-1,48). La pyrexie était plus de deux fois plus fréquente chez les femmes ayant reçu ≥ 600 µg de misoprostol que chez celles ayant reçu une dose de 400 µg (RR : 2,53 ; IC à 95 % : 1,78-3,60).

Conclusion

Des recherches supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour évaluer plus précisément les effets bénéfiques et nocifs potentiels du misoprostol et pour identifier la plus faible dose de ce médicament à la fois efficace et sans risque. La présente étude a trouvé qu’une dose de 400 µg de misoprostol était plus sûre qu’une dose ≥ 600 µg et tout aussi efficace.

Resumen

Objetivo

Analizar la mortalidad materna y los efectos dosis-dependientes del misoprostol sobre la pérdida de sangre y en forma de fiebre en los ensayos aleatorizados realizados sobre su uso con fines de prevención o tratamiento de la hemorragia posparto.

Métodos

Utilizamos el Registro de Ensayos Controlados de Cochrane y Pubmed para realizar una búsqueda en todos los idiomas planteada en los siguientes términos: «(misoprostol AND postpartum) OR (misoprostol AND haemorrhage) OR (misoprostol AND hemorrhage)». Se procedió a evaluar los trabajos identificados mediante la estrategia de búsqueda del Grupo Cochrane de Embarazo y Parto, y se determinó la elegibilidad de los ensayos aleatorizados en que se comparó el misoprostol ya fuera con un placebo o con otro uterotónico como forma de prevención o tratamiento de la hemorragia posparto. Los datos extraídos fueron tabulados y analizados con el software Reviewer Manager (RevMan) 4.3.

Resultados

Incluimos en el análisis final 46 ensayos que abarcaron a más de 40 000 participantes. De las 11 defunciones notificadas en 5 ensayos, 8 correspondían a mujeres que habían recibido ≥ 600 µg de misoprostol (oportunidad relativa [OR] de Peto: 2,49; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 0,76–8,13). La morbilidad grave, definida como la necesidad de cirugía mayor, el ingreso en cuidados intensivos, la aparición de insuficiencia orgánica o una temperatura corporal ≥ 40 °C, fue relativamente poco frecuente. En los ensayos de prevención, sufrieron morbilidad grave 16 de las 10 281 mujeres a las que se administró misoprostol, y 16 de las 10 292 mujeres sometidas a uterotónicos convencionales; en los ensayos de tratamiento, sufrieron cuadros graves 1 de 32 mujeres sometidas a misoprostol y 1 de 32 mujeres tratadas con uterotónicos convencionales. Quienes recibieron misoprostol sufrieron más eventos adversos que quienes recibieron placebo: 8 de 2070 frente a 5 de 2032, respectivamente, en los ensayos de prevención, y 5 de 196 frente a 2 de 202, respectivamente, en los ensayos de tratamiento. El metanálisis de las comparaciones directas e indirectas ajustadas de los resultados de los ensayos aleatorizados no aportó ningún indicio de que la dosis de 600 µg sea más eficaz que la de 400 µg para prevenir las hemorragias ≥ 1000 ml (riesgo relativo, RR: 1,02; IC95%: 0,71–1,48). La frecuencia de fiebre entre las mujeres que recibieron ≥ 600 µg de misoprostol fue más del doble que en las tratadas con 400 µg (RR: 2,53; IC95%: 1,78–3,60).

Conclusión

Es necesario realizar nuevas investigaciones para evaluar con más precisión los posibles efectos beneficiosos y nocivos del misoprostol y para determinar la dosis más baja eficaz y segura. Según los resultados de este análisis, las dosis de 400 µg de misoprostol son más seguras que las dosis ≥ 600 µg y tienen la misma eficacia.

ملخص

الهدف

لمراجعة وفيات الأمهات والتأثيرات المتعلقة بجرعة الميزوبروستول على فقدان الدم وعلى الحمّى في التجارب المعشَّاة حول استخدام الميزوبروستول للوقاية من النزف التالي للولادة ومعالجته.

الطريقة

بحث الباحثون في سجل كوكران للتجارب المعشَّاة وPubMed، دون أي قيودٍ لغوية، عن كلمات (ميزوبروستول وتال للولادة) أو (ميزوبروستول ونزف) أو (ميزوبروستول ونزف دموي)، وأجروا تقيـيماً للتقارير التي تعرفوا عليها من خلال استراتيجية البحث في مجموعة كوكران للحمل والولادة. وتحقق الباحثون من التجارب المعشاة التي تقارن بين الميزوبروستول مع دواء غُفْل أو دواء آخر موتّر للرحم بهدف الوقاية من النزف التالي للولادة أو معالجته، من حيث الملاءمة. وقد استخدم الباحثون برنامج إدارة المراجعة (RevMan) بإخراجته الرابعة لاستخلاص المعطيات، وجَدْوَلتها وتحليلها.

الموجودات

ضم التحليل النهائي 46 دراسة شارك فيها ما يزيد على 000 40 مشاركة، ومن بين 11 وفاة أُبلغَ عنها في 5 تجارب، حدثت 8 وفيات لدى نسوة تلقّيْن ما يزيد على 600 مكروغرام من الميزوبروسترول (نسبة الأرجحية لبيتو 49.2، وفاصلة الثقة 95%: 0.76 – 8.13). وكان من النادر نسبياً حصول مراضة وخيمة تعرَّف بأنها تستدعي إجراء جراحة كبرى أو إدخال إلى الرعاية المركَّزة، أو فشل أحد الأعضاء، أو ارتفاع درجة حرارة الجسم لأكثر من 40 ْ سيلزيوس. وفي التجارب الخاصة بالوقاية، عانت من مراضة وخيمة، 16 امرأة من بين 281 10 امرأة ممن تلقّيْن الميزوبروستول، و16 امرأة من بين 292 10 تلقّيْن المعالجة التقليدية الموتّرة للرحم. أما في التجارب الخاصة بالمعالجة، فقد عانت من مراضة وخيمة، امرأة واحدة من بين 32 امرأة ممن تلقّيْن الميزوبروستول، وامرأة واحدة من بين 32 امرأة تلقّيْن المعالجة التقليدية. وهكذا عانت النسوة اللاتي تلقين الميزوبروستول من أحداث ضائرة أكثر مما عانت منها النسوة اللاتي تلقَيْن الدواء الغُفل: حيث عانت 8 من بين 2070 من النسوة اللاتي تلقّيْن الميزوبروستول من أحداث ضائرة، وهو أكثر مما عانت منه النساء اللاتي تلقّيْن دواءً غفلاً وهن 5 من أصل 2032؛ وذلك في التجارب الوقائية، أما في تجارب المعالجة، فقد عانت 5 من أصل 196 ممن تلقّيْن الميزوبروستول، من أحداث ضائرة، فيما عانت 2 من أصل 202 ممن تلقّيْن المعالجة بالدواء الغفل. وقد أوضح التحليل التلوي للمقارنات المباشرة والمقارنات غير المباشرة المعدلة لنتائج التجارب المعشّاة عدم وجود بينة على أن إعطاء 600 مكروغرام هو أكثر فعالية من إعطاء 400 مكروغرام للوقاية من فقدان 1000 ميلي لتر أو أكثر من الدم (فالاختطار النسبي 1.02 بفاصلة ثقة 95 %: 0.71 – 1.48). وقد كانت الحمى أكثر شيوعاً لدى من تلقّين أكثر من 600 مكروغرام من الميزوبروستول، بمقدار الضعف مما كانت عليه لدى اللاتي تلقّيْن 400 مكروغرام منه (الاختطار النسبي 2.53، وفاصلة الثقة 95%: 1.78– 3.60).

الاستنتاج

تمس الحاجة إلى المزيد من البحوث للحصول على تقيـيم أكثر دقة للتأثيرات المفيدة المحتملة وللتأثيرات الضائرة لاستخدام الميزوبروستول، وللتعرف على الجرعة الأصغر التي تـتمتع بالفعالية (النجاعة) والمأمونية. وقد وجد الباحثون في هذه الدراسة أن جرعة مقدارها 400 مكروغرام من الميزوبروستول تعد أكثر مأمونية من جرعة مقدارها 600 مكروغرام منه، رغم أنها تـتمتع بنفس القدر من الفعّالية (النجاعة).

Introduction

In low-income countries, postpartum haemorrhage is a major cause of maternal death1 and arguably the most preventable. Attempts to reduce deaths from postpartum haemorrhage have been complicated by the fact that many deaths occur in out-of-hospital settings or too quickly for the patient to be transferred to a health facility. Furthermore, prevention and treatment have depended primarily on injectable uterotonics, which are seldom available for births outside the health system. For these reasons, the use of misoprostol to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage has attracted considerable attention. Misoprostol, an inexpensive and stable prostaglandin E1 analogue, has been shown to stimulate uterine contractility in early pregnancy2 and at term.3 Administered orally or vaginally, it is effective for inducing abortion4,5 and labour,6–8 though it poses certain risks.9,10

Administration of this drug on a wide scale at the community level to prevent and treat postpartum haemorrhage is of major public health importance. The first of many randomized trials of the use of misoprostol in the third stage of labour was conducted in 1995.11 When administered in various doses and via various routes for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage, misoprostol has been less effective than conventional injectable uterotonics.12,13 Initial reports of placebo-controlled trials have shown variable results,12 but in more recent studies misoprostol has proved better than placebo, in terms of measured blood loss, for both the prevention14,15 and treatment16 of postpartum haemorrhage. The main side effects reported have been chills and pyrexia, both of which have been dose-dependent.17

We have reviewed the pharmacological, physiological and clinical evidence surrounding the use of misoprostol for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage.16 The oral route of administration is the fastest but also the one associated with the shortest duration of action. The rectal route has slow uptake but a prolonged duration of action. The buccal and sublingual routes have rapid intake, prolonged duration of action and the greatest total bioavailability. We concluded from the data reviewed that the most promising route of administration was the sublingual route.

Misoprostol has been widely recommended to prevent postpartum haemorrhage when other methods are not available,18 and large-scale implementation projects are currently in progress. Caution has been urged, however, because side-effects may occasionally be life-threatening.19 In a recent placebo-controlled trial in rural India in which babies were delivered by auxiliary nurse midwives at home or in village subcentres, a significant reduction in postpartum haemorrhage and other complications was obtained with misoprostol, 600 µg orally used alone (i.e. without other components of the active management of the third stage of labour – umbilical cord clamping and controlled cord traction).15 WHO has developed guidelines supporting the use of a uterotonic when the full package of active management of the third stage of labour is not practised, which can be either oxytocin, 10 IU administered parenterally, or misoprostol, 600 µg administered orally.20

Apart from its uterotonic effects, misoprostol has known pharmacologic effects on several organ systems. It inhibits platelet-activating factor21 and affects metabolic and physiological processes, including thermoregulation. Life-threatening hyperpyrexia has been reported following the use of misoprostol, 800 µg orally, after childbirth.22

Whenever a new medical intervention is promoted, one must take into account not only its clinical benefits and risks, but also the collateral benefits and risks from both use and potential misuse in the community. Before distributing misoprostol at the community level, it is important to consider its possible misuse, an example being its administration before delivery, which could lead to uterine rupture. Because of its enormous potential benefits as an effective, oral uterotonic during the third stage of labour and its likely use on a large scale worldwide, it is important to monitor misoprostol’s benefits as well as its potential risks, both direct and indirect.

In September 2005, the BMJ published the first placebo-controlled trial to suggest a clear effect of misoprostol for preventing postpartum haemorrhage.14 The study elicited several responses, however. One of them was the suggestion to regard the single maternal death in the misoprostol group as an adverse event potentially related to misoprostol use.23 This is plausible because a drug with ubiquitous pharmacologic effects might have unanticipated adverse effects when used in the third stage of labour. Another response was a call for a trial of misoprostol as a treatment for postpartum haemorrhage, with maternal death as the primary endpoint.24

In this paper we hypothesized that women on misoprostol in the third stage of labour were at increased risk of death or severe morbidity because of an as yet unexplained adverse effect of the drug on maternal homeostatic functions.25 Thus, the primary objectives of this review was to investigate maternal deaths and severe morbidity in connection with the use of misoprostol for preventing or treating postpartum haemorrhage during the third stage of labour, as well as to see whether side effects were dose-related. A secondary objective was to determine the relative effectiveness of ≥ 600 µg of misoprostol versus smaller doses, since to justify the use of the larger dose in large numbers of women, particularly in light of potential side effects, would require evidence that it is considerably more effective than the smaller dose.

Methods

Systematic review

Types of studies: We performed a systematic review of randomized controlled trials in which misoprostol versus either placebo or another uterotonic were given to women after delivery to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage. We looked for the following primary outcome measures: (i) maternal death, or (ii) maternal death or severe morbidity, defined as either major surgery, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), vital organ failure or body temperature ≥ 40 °C. For dose comparisons, the outcomes selected were a blood loss of ≥ 1000 ml or of ≥ 500 ml after the diagnosis of postpartum haemorrhage, and pyrexia (i.e. a body temperature ≥ 38 °C or as defined by trial authors).

Search strategy

We followed the search strategy used by the Cochrane Collaboration’s Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. Briefly, potentially eligible trials were identified from: (i) quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); (ii) monthly searches of Medline; (iii) hand searches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences; and (iv) weekly current awareness searches of a further 37 journals. We also searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and Pubmed, without language restrictions, for “(misoprostol AND postpartum) OR (misoprostol AND haemorrhage) OR (misoprostol AND hemorrhage)” (last search February 2007). We tried to contact authors to obtain further details about any maternal deaths reported and, if no maternal death was mentioned in a paper, we asked the authors to confirm that no death had occurred.

All studies identified through the search strategy were assessed for inclusion in the analysis. We designed a data extraction form that was used by two of the authors, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion. We used Review Manager (RevMan) 4 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) to enter the data and check it for accuracy.

Assessment of methodological quality

For each trial we classified allocation concealment as follows: (i) adequate if a method such as telephone randomization or consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes was used; (ii) unclear if the concealment method was not described; or (iii) inadequate if an open list of random numbers, case record numbers, dates of birth, days of the week or another such method was used.

Measures of treatment effect and assessment of heterogeneity

We used fixed effects meta-analysis for combining data in the absence of significant heterogeneity. For dichotomous data, we presented the results as summary relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For the outcome maternal mortality, we used both RRs and Peto odds ratios (ORs) to check for discrepancies between the two summary statistics. Peto ORs are recommended when events are very infrequent. We applied tests of heterogeneity between trials using the I² statistic, a variation of the χ² statistic.

Subgroup analyses

We classified whole trials according to interaction tests as described by Deeks et al.26 and carried out the following subgroup analyses: (i) misoprostol versus placebo and versus other uterotonics; (ii) misoprostol to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage; and (iii) misoprostol at a dose of ≥ 600 µg or more; 400 to < 600 µg; or < 400 µg.

In the analysis tables we ranked the trials by route of administration and dose of misoprostol to check for route- or dose-related trends in effects. We coded the trial identifiers to indicate the route of administration and dose used.

Comparisons of dose-related effectiveness and side-effects

In view of inadequate data from direct randomized comparisons of different doses of misoprostol, we supplemented the direct data with adjusted indirect comparisons. In most cases, the results of adjusted indirect comparisons have proved similar to those of direct comparisons in 44 previous meta-analyses.27 Thus, to estimate the relative effectiveness of two different doses of misoprostol we combined the results of trials in which each dose of the drug was tested against the same type of control (either placebo or a uterotonic other than misoprostol).28 Three-way comparisons of 600 µg versus 400 µg of misoprostol versus placebo or another uterotonic were included only in the direct comparisons. Studies of rectally-administered misoprostol were excluded because of uncertain absorption via the rectal route.

For direct and indirect comparisons the primary outcome measures were blood loss ≥ 1000 ml and pyrexia ≥ 38 °C. As the effectiveness outcome was blood loss measured within 1 hour of drug administration, doses of misoprostol given 1 hour or more after the initial dose were not taken into account.

Most of the trials in the review were conducted in settings with routine active management of the third stage of labour. To determine if such management affected the results, we performed a sensitivity analysis from which we excluded the one trial in which active management was not practiced.15

Prospective adverse-event surveillance studies

We report on adverse events from misoprostol use as recorded in the WHO Adverse Reaction Database, maintained by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC), which is the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring. The UMC collects reports of suspected adverse drug reactions from 70 participating countries. We ranked adverse events by frequency of reporting.

Results

Systematic review

We found 46 randomized controlled trials with more than 40 000 participants. They are summarily described in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies included in a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of misoprostol for preventing or treating postpartum haemorrhage.

| Studya [Allocation concealmentb] | Intervention | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia 1999: 400 PO vs U13: Not blinded. Randomization by table, in balanced blocks. [A] | M 400 µg PO vs oxytocin (10 IU) or vs oxytocin (5 IU) + ergometrine 0.5 mg IM | 3rd stage of labour management not mentioned. Blood loss both estimated and measured. | ||

| Belgium 1999: 600 PO vs U15: Outcome blinded. Randomization generated by computer; blocks allocation from computer-generated list of study numbers. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs methylergometrine 200 µg IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss assessment not described. | ||

| Canada 2002: 400 PR vs U29: Not blinded. Central centre statistician performed block randomization for participating centres. [A] | M 400 µg PR after delivery vs oxytocin 5 IU IV or IM, or 10 IU IM | 3rd stage management and blood loss measurement not described. | ||

| Canada 2007:400 PO vs U30: Not blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PO vs oxytocin 5 IU IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss estimated visually and measured. | ||

| China 2001: 600 PO vs U31: Outcome not blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs oxytocin 5 IU + ergometrine 0.5 mg IM | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss estimated clinically. | ||

| China 2004a: 600 SL vs U32: Not blinded. Randomization by random numbers table. [C] | M 600 µg SL vs syntocinon 5 IU + ergometrine 0.5 mg IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss estimated visually and measured. | ||

| China 2004b: 400 PO vs P33: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PO vs syntometrine 1 ampoule IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour and blood loss assessment not described. | ||

| China 2007: 400 PO vs U34: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PO after delivery vs syntometrine 1 ampoule IM | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss estimated clinically. | ||

| Colombia 2002: 50 SL vs U35: Not blinded. Randomization method not stated. [B] | M 50 µg SL vs oxytocin 16 mIU/min IV vs methylergometrine 0.2 mg IM | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| France 2001: 600 PO vs P vs U36: Not blinded. Randomization by drawn envelopes containing treatment codes. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs oxytocin 2.5 IU IV vs no uterotonic | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Gambia 2004:600 PO/SL vs P37: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO & SL vs placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Gambia 2005: 600 PO vs P38: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Ghana 2000: 400 PO vs U39: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg in powdered form PO (in 50 ml of water) and 1 ml IM injection of normal saline (placebo) vs powdered lactose placebo PO (in 50 ml of water) and 1 ml IM 10 IU oxytocin | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss assessment not described. | ||

| Ghana 2006: 800 PR vs U40: Not blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 800 µg PR vs oxytocin 10 IU IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour and blood loss assessment not described. | ||

| Guinea-Bissau 2005: 600 SL vs P14,41: Outcome not blinded. Randomization by random numbers list. [A] | M 600 µg SL vs identical placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| India 2004a: 400 SL vs U42: Unclear if outcome assessments were blinded. Randomization by sealed, consecutively numbered envelopes. [A] | M 400 µg SL vs methylergometrine 0.2 mg IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| India 2005: 600 PO vs U43: Unclear if outcome assessments were blinded. Random allocation, no further details. [B] | M 600 µg PO vs methylergometrine 0.2 mg IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss assessment not mentioned. | ||

| India 2006a: CS 400 vs SL vs U44: Unclear if outcome assessments were blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [B] | M 400 µg SL vs 20 IU oxytocin in 1 L lactated Ringer’s solution at 125 ml/h. | Management of 3rd stage of labour and blood loss assessment not described. All women had Caesarean section with spinal anaesthesia. | ||

| India 2006b: 400 PO vs U45: No mention of blinding. Randomization generated by computer. [B] | M 400 µg PO vs oxytocin 10 IU IM vs ergometrine 0.2 mg IV | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| India 2006c: 600 PO vs P46: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs identical placebos | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| India 2006d: 400 PR vs U47: Interventions administered “randomly”. [B] | M 400 µg PR vs carboprost 125 µg IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss assessed clinically. | ||

| India 2006e: 400 SL vs U48: Double blinded. Randomization method not described. [A] | M 400 µg SL vs ergometrine 0.2 mg IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| India 2006f: 600 PR vs U49: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PR vs oxytocin 10 IU IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Indonesia 2002: 600 PO vs U50: Randomization method not described. [B] | M 600 µg PO vs oxytocin 10 IU IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured, method not described. | ||

| Mozambique 2001: 400 PR vs U51: Double blinded. Randomization generation unclear. Double placebos prepared daily by pharmacist independent of the trial and provided to the researchers upon request. [B] | M 400 µg dissolved in 5 ml saline PR as a microenema + 1 ml saline placebo IM vs oxytocin 10 IU IM + 5 ml saline microenema (placebo) | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Nigeria 2003: 600 PO vs U52: Double blinded. Randomization by random number table. [A] | M 600 µg in powder form dissolved in 50 ml water PO vs oxytocin 10 IU IM | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss assessed clinically. | ||

| South Africa 1998a: 400 PR vs U53: Not blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PR vs ergometrine-oxytocin 1 ampoule IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| South Africa 1998b: 400 PO vs P11: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PO vs placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| South Africa 1998c: 400 PR vs P54: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 400 µg PR vs placebo | Active or expectant management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| South Africa 1998d: 600/400 PO vs P55,56: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs M 400 µg PO vs placebo | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| South Africa 2001a: 600 PO vs P55: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs placebo | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| South Africa 2001b: 800 PR vs U57: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 800 µg PR vs oxytocin 5 IU IM vs ergometrine 0.5 mg IM | Women with postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal delivery or Caesarean section. Blood loss assessed clinically. | ||

| South Africa 2004: 1000 PO/SL/PR vs P58: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | M 200 µg PO + 400 µg SL + 400 PR vs placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Switzerland 1999: 600 PO vs P59: Double blinded. Randomization by random number table. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs placebo | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss estimated by pre- and post-delivery haemoglobin and haematocrit. | ||

| Switzerland 2006: CS 800 PO vs U60: Double blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | oxytocin 5 IU IV + M 800 mg vs oxytocin 5 IU IV + oxytocin 20 IU in 1000 ml normal saline over 8 hours. | All patients had Caesarean section. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Turkey 2002: 400 PR vs P/U61: Outcome blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | 4 groups, all received corresponding placebos. Group 1: oxytocin 10 IU IV + M 400 µg PR, followed by 2 doses, 4 and 8 hours after delivery, of M 100 µg. Group 2: M as above. Group 3: oxytocin 10 IU IV. Group 4: oxytocin 10 IU IV plus methylergometrine 1 ml IM | Management of 3rd stage of labour and blood loss assessment not described. | ||

| Turkey 2003: 400 PO vs P/U62: Outcome blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [A] | Group 1: oxytocin 10 IU IV + M 400 µg PO, followed by 2 doses, 4 and 8 hours after delivery, of M 100 µg PO. Group 2: M as above. Group 3: oxytocin 10 IU IV. Group 4: oxytocin 10 IU IV plus methylergometrine 1 ml IM | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Turkey 2005: 400 V/R vs P63: Randomization generated by computer. [B] | M 400 µg PV or PR vs placebo | Expectant management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. Women with profuse haemorrhage or placental separation for > 30 min were excluded. | ||

| United Kingdom 2000: 500 PO vs U64: Not blinded. Randomization by sealed, opaque, consecutively numbered envelopes. [A] | M 500 µg PO vs ergometrine for women (2%) at high risk of haemorrhage; women with hypertension (18%) received oxytocin. All others (80%) received ergometrine-oxytocin. | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss assessed clinically. | ||

| United Kingdom 2001: 500 PO vs U65: Blinded. Randomization generated by computer. [B] | M 500 µg PO + normal saline 2 ml IV bolus vs oxytocin 10 IU IV bolus + 2 placebo tablets | All women underwent elective or emergency Caesarean section. Blood loss assessed clinically. | ||

| United States 2001:400 PR vs U66: Not blinded. Random allocation sequence concealed until enrolment. [B] | M 400 µg PR + placebo (2 ml saline) vs oxytocin 20 IU IV infusion in 1 L of Ringer’s lactate solution + placebo PR (lactose tablets) | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. | ||

| United States 2004: 200 B vs P67: Not blinded. Randomization by random number table. [B] | M 200 µg B vs placebo. All women received oxytocin 20 IU IV infusion in 1 L of normal saline at 10 ml/min for 30 minutes (i.e. received oxytocin, approximately 6 IU IV) | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| United States 2005: CS 200 B vs P68: Outcome blinded. No mention of random number generation scheme. Allocation concealment by pharmacy-assigned numbers to opaque vials containing either misoprostol tablets or oxytocin ampoules. [A] | M 200 µg B vs placebo. All women received oxytocin 20 IU IV in 1000 ml normal saline | All women underwent Caesarean section. Blood loss estimated following “standard” procedures. | ||

| WHO 1999: 400/600 PO vs U17: Double blinded. Randomization sequence generated centrally. [A] | M 600 µg PO vs M 400 µg PO vs oxytocin 10 IU IV | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| WHO 2001: 600 PO vs U69,70: Double blinded. Random allocation sequence generated centrally. [A] | M 600 µg PO + placebo IV/IM, vs oxytocin 10 IU IV/IM + placebo tablets | Active management of 3rd stage of labour. Blood loss measured. | ||

| Zimbabwe 2001:400 PO vs U71: Randomization generated by computer. Blinding not mentioned. [A] | M 400 µg PO + 1 ml saline (placebo) vs oxytocin 10 IU IM + 2 placebo tablets | Management of 3rd stage of labour not described. Blood loss measured. |

a The format used for study identifiers was as follows: country, year, misoprostol (M) dose in micrograms (µ), route of administration (B = buccal; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; PO = oral; PR = rectal; SL = sublingual), misoprostol compared with (vs) placebo (P) or another uterotonic (U). b Concealment allocation code: A: adequate; B: unclear; C: inadequate.

Maternal deaths

Maternal deaths were reported in five trials.14,15,38,58,69 Three other trials specified that there were no maternal deaths.30,39,71 No additional maternal deaths were identified through communication with the authors of the included trials.

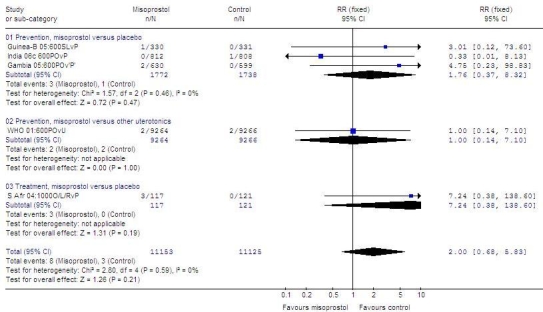

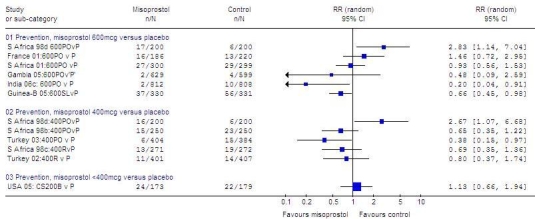

Fig. 1 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html) shows only the five trials in which maternal deaths were reported. Of 11 deaths reported in these trials,14,15,38,58,69 8 occurred in women receiving misoprostol (RR: 2.0; 95% CI: 0.68–5.83; Peto OR: 2.49; 95% CI: 0.76–8.13). Of 8 maternal deaths reported in the misoprostol group, 6 were associated with postpartum haemorrhage.14,38,58

Fig. 1.

Maternal deathsa reported in randomized trials of misoprostolb versus placebo or another uterotonic to prevent or treat PPH

CI, confidence interval; Guinea-B, Guinea-Bissau; L or SL, sublingual; O or PO, oral; P, placebo; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; R, rectal; RR, relative risk; S Afr, South Africa; U, uterotonic other than misoprostol.

a Trials that did not report maternal deaths are not shown. The denominators for all trials are 21 814 for misoprostol groups and 22 526 for control groups. Meta-analysis with all trials included yielded the same RR and 95% CI.

b Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Severe maternal morbidity

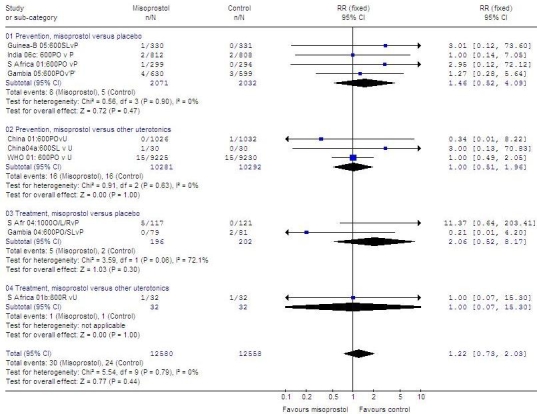

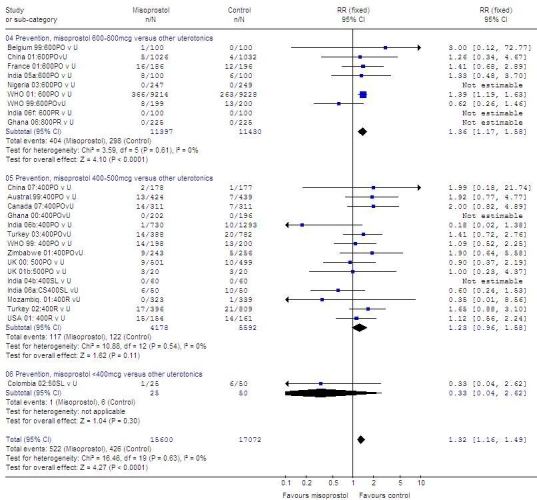

Fig. 2 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html) shows the data on maternal deaths and severe morbidity as reported in the randomized controlled trials of misoprostol compared with placebo or other uterotonics to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage. When misoprostol was compared with other uterotonics, a similar number of adverse events was reported in both prevention and treatment trials: in prevention trials, 16 of 10281 versus 16 of 10292 women, respectively (RR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.51–1.96); in treatment trials, 1 of 32 women in the treatment as well as the control group (RR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.07–15.30). When misoprostol was compared with placebo, slightly more adverse events were reported in the misoprostol group in both prevention and treatment trials: in prevention trials, 8 of 2070 versus 5 of 2032 women, respectively (RR: 1.46; 95% CI: 0.52–4.09); in treatment trials, 5 of 196 versus 2 of 202 women, respectively (RR: 2.06; 95% CI: 0.52–8.17). Events were too few to draw any conclusions.

Fig. 2.

Randomized trialsa of misoprostolb versus placebo or another utrotonic to prevent or treat PPH

CI, confidence interval; Guinea-B, Guinea-Bissau; L or SL, sublingual, O or PO, oral; P, placebo; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; R, rectal; RR, relative risk; S Africa, South Africa; U, uterotonic other than misoprostol.

a Outcome variables: maternal death or severe morbidity.

b Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Table 2 presents descriptions of cases of maternal death and morbidity reported in the trials. In a study from India,15 one maternal death in the placebo group was not related to haemorrhage. In the WHO (2001) study,69 the causes of two deaths in the injectable uterotonic group were not mentioned. A few studies reported admission of the participants to the ICU. One of them was the WHO (2001) study, in which 9 women were admitted to the ICU: 4 of 9224 in the misoprostol group and 5 of 9231 in the injectable uterotonic group (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.22–2.98).69 In a recent study from India, 4 participants were admitted to the ICU: 2 of 812 in the misoprostol group and 2 of 808 in the placebo group.15

Table 2. Maternal deaths and severe morbidity reported in randomized controlled trials of misoprostol to prevent or treat postpartum haemorrhage.

| Studya | Misoprostol group | Control group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China 2001: 600 PO vs U31 | No cases | 1 hysterectomy in multiparous woman with PPH (5 L) due to uterine atony | ||

| China 2004a: 600 PO vs U32 | PPH (4 L) due to uterine atony in primiparous woman | No cases | ||

| Gambia 200437: 600 PO/SL vs P | No cases | 2 hysterectomies, no details reported | ||

| Gambia 200538: 600 PO vs P | 1 maternal death from PPH (2.2 L) in gravida 7, para 6, delivered at home | 1 hospital admission for PPH and clinical anaemia | ||

| 1 maternal death from disseminated intravascular coagulation due to malaria | 2 hospital admissions for severe postpartum anaemia | |||

| 2 hospital admissions from severe postpartum anaemia | ||||

| Guinea-Bissau 200514,41: 600 SL vs P | 1 maternal death, PPH (1.4 L), cause of death not established on autopsy | No cases | ||

| India 2006c46: 600 PO vs P | 2 ICU admissions | 2 ICU admissions | ||

| South Africa 2001a55: 600 PO vs P | 1 case of fever > 40 °C | No cases | ||

| South Africa 2001b57: 80 PO vs U | 1 internal iliac artery ligation for severe PPH | 1 hysterectomy for severe PPH | ||

| South Africa 200458: 1000 PO/SL/PR vs P | 1 maternal death from severe PPH, coagulopathy, had hysterectomy, died on day 2 postpartum | No cases | ||

| 1 maternal death from severe PPH (3 L) secondary to cervical tear, coagulopathy | ||||

| 1 maternal death from PPH (1 L), hypotension and cardiac arrest, possibly had internal bleeding from dehisced Caesarean section scar | ||||

| 2 hysterectomies for PPH | ||||

| WHO 200169,70: 600 PO vs U | 2 maternal deaths | 2 maternal deaths | ||

| 4 hysterectomies | 8 hysterectomies | |||

| 4 ICU admissions | 5 ICU admissions | |||

| 5 cases of fever > 40 °C |

ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravascular; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage. a The format used for study identifiers was as follows: country, year, misoprostol (M) dose in micrograms (µ), route of administration (IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; PO = oral; PR = rectal; SL = sublingual), misoprostol compared with (vs) placebo (P) or another uterotonic (U).

Blood loss ≥ 1000 ml

In the initial analysis of misoprostol versus placebo (Fig. 3, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html), significant heterogeneity (I²: > 50%) was noted in the results for 600 µg (4914 women; RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.54–1.57; I²: 66%) and for 400 µg (3039 women; RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.47–1.37, random effects model; I²: 58%). The heterogeneity could not be accounted for by route of administration or trial quality. Rather, it appeared to be related to a single outlier study that contributed data to both subgroups. Removal of this study from the meta-analysis eliminated the significant heterogeneity (I²: < 50%). After exclusion of the outlier, less blood loss ≥ 1000 ml was noted with 600 µg of misoprostol (4514 women; RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.59–1.00, trend, fixed effects model) and with 400 µg of misoprostol (2642 women; RR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.44–0.91) than with placebo.

Fig. 3.

Randomized trials of misoprostola versus placebo to prevent PPH, effect on blood loss ≥ 1000 ml

CB, buccal; CI, confidence interval; CS, Caesarean section; SL, sublingual; P, placebo; PO, oral; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; R, rectal; RR, relative risk; S Africa, South Africa; USA, United States of America.

a Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

In one small trial in which 200 µg of misoprostol were compared with placebo (in addition to an oxytocin infusion in both groups) at Caesarean section, no statistically significant difference in blood loss ≥ 1000 ml was found (misoprostol versus placebo: 352 women; RR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.66–1.94).

When misoprostol was compared with other uterotonics (Fig. 4, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html), results showed no heterogeneity (I²: 0%). Misoprostol, at a dose of 600 to 800 µg, was less effective than other uterotonics (22 827 women; RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.17–1.58). Furthermore, the results obtained with 400–500 µg of misoprostol did not differ significantly from those obtained with 600 µg (9772 women; RR: 1.23; 95% CI: 0.96–1.58), even though the sample size was smaller than for the 600–800 µg doses, the direction of the trend was the same.

Fig. 4.

Randomized trials of misoprostola versus another uterotonic to prevent PPH, effect on blood loss ≥ 1000 ml

CI, confidence interval; CS, Caesarean section; PO, oral; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; R or PR, rectal; RR, relative risk; S Africa, South Africa; SL, sublingual; U, uterotonic other than misoprostol; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

a Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

In one small trial in which misoprostol at a dose of 50 µg administered sublingually was compared with injectable uterotonics, no significant difference was found (75 women; RR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.04–2.62).

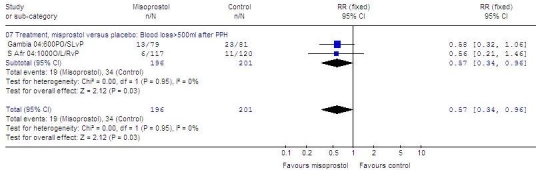

When given in addition to routine methods of treatment (Fig. 5, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html), 600–1000 µg of misoprostol in split doses orally, sublingually and/or rectally was more effective than placebo at reducing an additional blood loss ≥ 500 ml after postpartum haemorrhage (397 women; RR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.34–0.96).

Fig. 5.

Randomized trials of misoprostola versus placebo to treat PPH, effect on additional blood loss ≥ 500 ml following postpartum haemorrhage

CI, confidence interval; L or SL, sublingual; PO, oral; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; R, rectal; RR, relative risk; S Africa, South Africa.

a Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

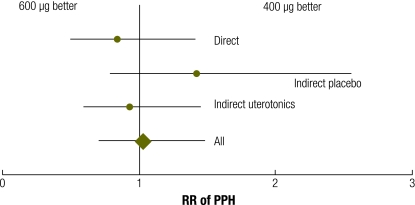

Meta-analysis of direct and adjusted indirect data from randomized trials showed no evidence of a benefit of 600 µg over 400 µg of misoprostol for reducing blood loss ≥ 1000 ml (RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.71–1.48; Table 3 and Fig. 6, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/9/08-055715/en/index.html). A sensitivity analysis excluding the one trial in which active management was not practised15 produced similar results (data not shown).

Table 3. Meta-analysis of direct comparisons and adjusted indirect comparisons of misoprostol, another uterotonic or placebo for risk of PPH.

| PPH (≥ 1000 ml of blood) | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Direct comparison, M, 600 µg vs 400 µg | 0.841 | 0.501–1.411 |

| Indirect adjusted comparison, M, 600 µg or 400 µg, vs P | 1.420 | 0.790–2.555 |

| Indirect adjusted comparison, M, 600 µg or 400 µg, vs U | 0.931 | 0.599–1.446 |

| All | 1.023 | 0.707–1.481 |

CI, confidence interval; M, misoprostol; P, placebo; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; RR, relative risk; U, uterotonic besides misoprostol.

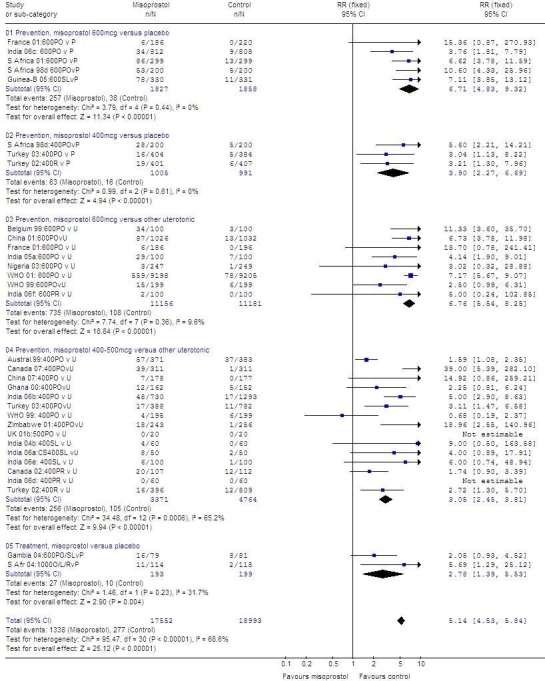

Fig. 6.

Randomized trials of misoprostola versus placebo or another uterotonic to prevent or treat PPH, effect on pyrexia (body temperature [t] ≥ 38 ºC or as defined by trial authorsb)

CI, confidence interval; Guinea-B, Guinea-Bissau; L or SL, sublingual, O or PO, oral; P, placebo; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; PR or R, rectal; S Afr or S Africa, South Africa; U, uterotonic other than misoprostol; UK, United Kingdom.

a Misoprostol dose always in micrograms.

b t > 37.1 ºC in India 06b; t ≥ 37.3 ºC in Australia 99; t ≥ 37.5 ºC in Gambia 04 and Ghana 04; t ≥ 37.8 ºC in S Africa 98d, 01; t > 37.9 ºC in Canada 02; t > 38 ºC in Canada 07, Turkey 02, Turkey 03, WHO 99, WHO 01 and Zimbabwe 01; t ≥ 38 ºC in Belgium 99, China 01, China 07, France 01, India 04b, India 06f, Guinea-B 05 and Nigeria 03; t ≥ 38.5 ºC in S Africa 04; t > 39 ºC in France 01; t undefined in India 05a, India 06a, India 06c, India 06d and India 06e.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Pyrexia

Pyrexia (body temperature ≥ 38 °C or as defined by authors) was higher among women who were given misoprostol in all subgroups (Fig. 7). There was quantitative but not qualitative heterogeneity in the subgroup in which misoprostol, at a dose of 400–500 µg, was compared with other uterotonics (I² = 65%). Such heterogeneity could not be explained by route of administration or trial quality.

Fig. 7.

Meta-analysisa of direct comparisons (misoprostol, 600 µg vs 400 µg) and adjusted indirect comparisons (misoprostol, 600 µg or 400 µg versus another uterotonic or placebo) for risk of PPH

PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; RR, relative risk.

a Each horizontal bar represents the 95% confidence interval.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

In comparisons with both placebo and other uterotonics, 600 µg of misoprostol produced pyrexia more often than 400–500 µg: misoprostol, 600 µg versus placebo: 3685 women; RR: 6.71; 95% CI: 4.83–9.32; misoprostol, 400 µg versus placebo: 1996 women; RR: 3.90; 95% CI: 2.27–6,69; misoprostol, 600 µg versus other uterotonics: 22 337 women; RR: 6.76; 95% CI: 5.54–8.25; misoprostol, 400–500 µg versus other uterotonics: 8135 women; RR: 3.05; 95% CI: 2.45–3.81. In the two treatment trials, pyrexia was more common in the misoprostol group (392 women; RR: 2.78; 95% CI: 1.39–5.53).

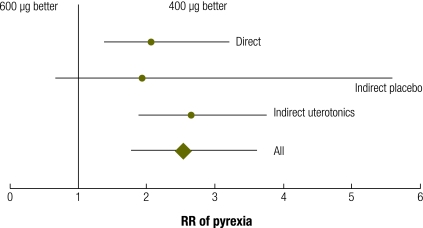

In meta-analysis of direct and adjusted indirect data from randomized trials, pyrexia was more common in the group given 600 µg of misoprostol rather than 400 µg (RR: 2.53; 95% CI: 1.78–3.60; Table 4 and Fig. 8). There was consistency between the estimates derived from the direct and the adjusted indirect comparisons.

Table 4. Meta-analysis of direct comparisons and adjusted indirect comparisons of misoprostol, another uterotonic, or placebo for risk of pyrexia.

| Pyrexia (body temperature ≥ 38 °C) | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Direct comparison, M, 600 µg vs 400 µg | 2.059 | 1.399–3.031 |

| Indirect adjusted comparison, M, 600 µg or 400 µg, vs P | 1.944 | 0.676–5.596 |

| Indirect adjusted comparison, 600 µg or 400 µg, vs U | 2.656 | 1.878–3.758 |

| All | 2.532 | 1.779–3.604 |

CI, confidence interval; M, misoprostol; P, placebo; RR, relative risk; U, uterotonic besides misoprostol.

Fig. 8.

Meta-analysisa of direct comparisons (misoprostol, 600 µg vs 400 µg) and adjusted indirect comparisons (misoprostol, 600 µg or 400 µg versus another uterotonic or placebo) for risk of pyrexia (body temperature [t] ≥ 38 ºC or as defined by trial authors)

RR, relative risk.

a Each horizontal bar represents the 95% confidence interval.

Graph generated by Review Manager (RevMan) 4.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Prospective surveillance of adverse events

The 14 most frequent adverse events associated with misoprostol use in the WHO Adverse Reaction Database were as follows (an association does not imply causality): diarrhoea (1001), abdominal pain (687), nausea (394), haemorrhage (294), abortion (209), vomiting (209), dyspepsia (162), flatulence (154), dizziness (152), menorrhagia (125), vaginal haemorrhage (153) and fever (98). Death (53) was the 23rd most common adverse event. Without details of the clinical situations in which these complications occurred, it is not possible to draw conclusions from the data.

Discussion

Misoprostol is used in the third stage of labour primarily to prevent maternal death. Because this is such a rare outcome, no trials to date have been designed to assess the effect on mortality. However, the occurrence of several deaths in misoprostol trials has raised some concern.

It is difficult to evaluate rare adverse outcomes in randomized trials. However, the systematic review of misoprostol trials included in this study provides data on more than 40 000 women. In addition, we complemented our search with adverse events reported to an international centre for such events. To our knowledge, there are no other large population-based datasets or observational studies of maternal deaths or severe adverse outcomes potentially associated with misoprostol use.

Our systematic review of maternal mortality is limited, first, by the small number of deaths associated with misoprostol use and the wide 95% confidence intervals, which are consistent with anything from a modest reduction to a large increase in maternal deaths. Second, this was a post-hoc analysis in response to an observed clustering of maternal deaths, and the statistical calculations need to be interpreted with caution. We recommend prospective surveillance of all randomized trials for further evidence for or against our working hypothesis.

The idea that a drug may have proven benefits against a life-threatening condition yet increase mortality is counterintuitive, but such a thing is plausible. For example, class 1 antiarrhythmics were routinely administered to patients after myocardial infarction because of their proven suppression of ventricular premature depolarizations, a common cause of death after infarction. However, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 3549 patients who had suffered myocardial infarction and had left ventricular dysfunction, 1 year after randomization to blinded therapy mortality among drug-treated patients was 10%, compared with 5% in the placebo-treated group (P = 0.0006).72 Monitoring for unexpected adverse effects is critical before any new medical intervention is introduced.

The cause of death was given for some of the deaths reported in the trials. Some deaths were due to severe haemorrhage, while others did not seem to be directly related to haemorrhage. In addition, deaths were too few to allow for any meaningful interpretation of the role misoprostol or other therapeutic interventions may have played in them.

Although they do not prove our working hypothesis, these results do suggest that misoprostol may have as yet unexplained adverse effects on maternal homeostatic functions in the third stage of labour. The potential for serious side effects is particularly worrisome in connection with the use of misoprostol for preventing, rather than treating, postpartum haemorrhage, because to prevent a single case of postpartum haemorrhage one would need to treat very large numbers of women.

In estimating the relative effect of 600 µg versus 400 µg of misoprostol on postpartum haemorrhage, we used meta-analysis of direct and adjusted indirect comparisons of randomized trial data to improve the precision of the findings from direct comparisons alone. This method proved useful in an empirical study of 44 meta-analyses.27 We further validated the method by applying it to the same trials for the outcome pyrexia, for which direct data were reasonably precise because pyrexia was more common than haemorrhage. We found that the findings from adjusted indirect comparisons were consistent with those of direct comparisons.

In all studies in which maternal deaths were reported, misoprostol was given at a dose of ≥ 600 µg. Physiological studies have shown uterotonic effects with doses as low as 200 µg. Our direct and indirect comparisons of data from randomized trials showed no difference in effect size between 600 µg and 400 µg doses. Since misoprostol sometimes produces dose-related side effects such as pyrexia and chills, we suggest that research be undertaken to establish the smallest dose of the drug that is effective and safe.

Because of the enormous benefits of using an effective oral uterotonic in the third stage of labour and since misoprostol could be used in this manner on a large scale worldwide, further research is essential to better assess the potential beneficial and harmful effects of the drug. However, the use of misoprostol should not detract from international efforts to ensure that all childbearing women have access to conventional uterotonics that have been proven safe and effective. ■

Acknowledgements

We thank ME Stanton and PFA Van Look for their continuing support, and PFA Van Look for reviewing the manuscript. The Effective Care Research Unit, East London, South Africa, and the Reproductive Health and Research Department at WHO, in Geneva, Switzerland, conducted the systematic review.

Footnotes

Funding: The project was funded by the United States Agency for International Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368:1189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norman JE, Thong KJ, Baird DT. Uterine contractility and induction of abortion in early pregnancy by misoprostol and mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;338:1233–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariani Neto C, Delbin AL, do Val Junior R. Padrão tocográfico desencadeado pelo misoprostol. Rev Paul Med. 1988;106:205–8. [in Portuguese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubeny E, Baulieu EE. Activite contragestive de l’association au RU 486 d’une prostaglandine active par voie orale. C R Acad Sci III. 1991;312:539–45. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Refaey H, Templeton A. Early induction of abortion by a combination of oral mifepristone and misoprostol administered by the vaginal route. Contraception. 1994;49:111–4. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)90085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM, Alfirevic Z. Misoprostol for induction of labour: a systematic review. BJOG. 1999;106:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfirevic Z, Howarth G, Gaussmann A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour with a viable fetus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD001338. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD000941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmeyr GJ, Milos D, Nikodem VC, de Jager M. Limb reduction anomaly after failed misoprostol abortion. S Afr Med J. 1998;88:566–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmeyr GJ. Misoprostol in obstetrics and gynaecology--unregistered, dangerous and essential. S Afr Med J. 1998;88:535–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmeyr GJ, Nikodem VC, de Jager M, Gelbart BR. A randomised placebo controlled trial of oral misoprostol in the third stage of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:971–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gülmezoglu AM, Forna F, Villar J, Hofmeyr GJ. Prostaglandins for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000494. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook CM, Spurrett B, Murray H. A randomized clinical trial comparing oral misoprostol with synthetic oxytocin or syntometrine in the third stage of labour. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:414–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1999.tb03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Høj L, Cardoso P, Nielsen BB, Hvidman L, Nielsen J, Aaby P. Effect of sublingual misoprostol on severe postpartum haemorrhage in a primary health centre in Guinea-Bissau: randomised double blind clinical trial. BMJ. 2005;331:723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derman RJ, Kodkany BS, Goudar SS, Geller SE, Naik VA, Bellad MB, et al. Oral misoprostol in preventing postpartum haemorrhage in resource-poor communities: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1248–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmeyr GJ, Walraven G, Gulmezoglu AM, Maholwana B, Alfirevic Z, Villar J. Misoprostol to treat postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review. BJOG. 2005;112:547–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lumbiganon P, Hofmeyr J, Gülmezoglu AM, Pinol A, Villar J. Misoprostol dose-related shivering and pyrexia in the third stage of labour. WHO Collaborative Trial of Misoprostol in the Management of the Third Stage of Labour. BJOG. 1999;106:304–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick ML, Sanghvi HC, Kinzie B, McIntosh N. Preventing postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:267–75. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong YS, Su LL. Misoprostol for preventing PPH: some lessons learned. Lancet. 2006;368:1216–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69497-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO recommendations for the management of the third stage of labor and community perceptions and actions on postpartum haemorrhage: findings from a national survey in Ethiopia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies NM, Longstreth J, Jamali F. Misoprostol therapeutics revisited. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:60–73. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.1.60.34442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong YS, Chua S, Arulkumaran S. Severe hyperthermia following oral misoprostol in the immediate postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:703–4. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan SC. Inadequate reporting of safety issues from clinical trials in academic journals. BMJ 2006, rapid response to: Høj L, Cardoso P, Nielsen BB, Hvidman L, Nielsen J, Peter Aaby P. Effect of sublingual misoprostol on severe postpartum haemorrhage in a primary health centre in Guinea-Bissau: randomised double blind control trial. BMJ. 2005;331:723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloan SCWB, Blum J. Questions for authors regarding the effect of sublingual misoprostol on portpartum haemorrhage. BMJ 2006, rapid response to: Høj L, Cardoso P, Nielsen BB, Hvidman L, Nielsen J, Peter Aaby P. Effect of sublingual misoprostol on severe postpartum haemorrhage in a primary health centre in Guinea-Bissau: randomised double blind control trial. BMJ. 2005;331:723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Misoprostol in the third stage of labour and maternal mortality: a review: BMJ 2006, rapid response to: Høj L, Cardoso P, Nielsen BB, Hvidman L, Nielsen J, Peter Aaby P. Effect of sublingual misoprostol on severe postpartum heamorrhage in a primary health centre in Guinea-Bissau: randomised double blind control trial. BMJ. 2005;331:723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradbury MJ. Statistical methods of examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context London: BMJ Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;326:472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–91. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karkanis SG, Caloia D, Salenieks ME, Kingdom J, Walker M, Meffe F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of rectal misoprostol versus oxytocin in third stage management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24:149–54. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baskett TF, Persad VL, Clough HJ, Young DC. Misoprostol versus oxytocin for the reduction of postpartum blood loss. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97:2–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng PS, Chan AS, Sin WK, Tang LC, Cheung KB, Yuen PM. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of oral misoprostol and i.m. syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labour. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:31–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam H, Tang OS, Lee CP, Ho PC. A pilot-randomized comparison of sublingual misoprostol with syntometrine on the blood loss in third stage of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:647–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuen PM, Ng PS, Sahota DS. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of oral misoprostol in addition to intramuscular syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labour. In: 30th British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Glasgow,2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng PS, Lai CY, Sahota DS, Yuen PM. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of oral misoprostol and intramuscular syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labor. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;63:55–60. doi: 10.1159/000095498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penaranda WA, Arrieta OB, Yances BR. Manejo activo alumbramiento con misoprostol sublingual: un estudio clínico controlado en el Hospital de Maternidad Rafael Calvo de Cartagena. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2002;53:87–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benchimol M, Gondry J, Mention JE, Gagneur O, Boulanger JC. Place du misoprostol dans la direction de la deliverance. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2001;30:576–83. [in French] [Paris] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walraven G, Dampha Y, Bittaye B, Sowe M, Hofmeyr J. Misoprostol in the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage in addition to routine management: a placebo randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2004;111:1014–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walraven G, Blum J, Dampha Y, Sowe M, Morison L, Winikoff B, et al. Misoprostol in the management of the third stage of labour in the home delivery setting in rural Gambia: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005;112:1277–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walley RL, Wilson JB, Crane JM, Matthews K, Sawyer E, Hutchens D. A double-blind placebo controlled randomised trial of misoprostol and oxytocin in the management of the third stage of labour. BJOG. 2000;107:1111–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parsons S, Ntumy YM, Walley RL, Wilson JB, Crane JMG, Matthews K, et al. Rectal misoprostol vs intramuscular oxytocin in the routine management of the third stage of labour Proceedings of: 30th British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Glasgow,2004 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen BB, Høj L, Hvidman LE, Nielsen J, Cardoso P, Aaby P. Reduceret post partum-blødning efter sublingval misoprostol: et randomiseret dobbeltblindt klinisk studie i et udviklingsland - sekundærpublikation. Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168:1341–3. [in Danish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vimala N, Mittal S, Kumar S, Dadhwal V, Mehta S. Sublingual misoprostol versus methylergometrine for active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg P, Batra S, Gandhi G. Oral misoprostol versus injectable methylergometrine in management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:160–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vimala N, Mittal S, Kumar S. Sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin infusion to reduce blood loss at cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;92:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zachariah ES, Naidu M, Seshadri L. Oral misoprostol in the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;92:23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kodkany BS, Derman RJ. Evidence-based interventions to prevent postpartum hemorrhage: translating research into practice. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:S114–5. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nellore V, Mittal S, Dadhwal V. Rectal misoprostol vs. 15-methyl prostaglandin F2alpha for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:45–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verma P, Aggarwal N, Jain V, Suri V. A double-blind randomized controlled trial to compare sublingual misoprostol with methylergometrine for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94(Suppl 2):S137–8. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta B, Jain V, Aggarwal N. Rectal misoprostol versus oxytocin in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage - a pilot study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:S139–40. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dasuki D, Emilia O, Harini S. Randomized clinical trial: the effectiveness of oral misoprostol versus oxytocin in prevention of postpartum heamorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2002;28:46. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bugalho A, Daniel A, Faundes A, Cunha M. Misoprostol for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oboro VO, Tabowei TO. A randomised controlled trial of misoprostol versus oxytocin in the active management of the third stage of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:13–6. doi: 10.1080/0144361021000043146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bamigboye AA, Merrell DA, Hofmeyr GJ, Mitchell R. Randomized comparison of rectal misoprostol with Syntometrine for management of third stage of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:178–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.1998.770209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bamigboye AA, Hofmeyr GJ, Merrell DA. Rectal misoprostol in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage: a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1043–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hofmeyr GJ, Nikodem VC, de Jager M, Drakely A. Side-effects of oral misoprostol in the third stage of labour: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:432–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hofmeyr GJ, Nikodem VC, de Jager M, Drakely A, Gilbart B. Oral misoprostol for labour third stage management: randomised assessment of side effects. Proceedings of: 17th Conference on Priorities in Perinatal Care, Durban, South Africa,1998 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lokugamage AU, Sullivan KR, Niculescu I, Tigere P, Onyangunga F, El Refaey H, et al. A randomized study comparing rectally administered misoprostol versus Syntometrine combined with an oxytocin infusion for the cessation of primary post partum hemorrhage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:835–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080009835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hofmeyr GJ, Ferreira S, Nikodem VC, Mangesi L, Singata M, Jafta Z, et al. Misoprostol for treating postpartum haemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-16. [ISRCTN72263357] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Surbek DV, Fehr PM, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Oral misoprostol for third stage of labor: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:255–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lapaire O, Schneider MC, Stotz M, Surbek DV, Holzgreve W, Hoesli IM. Oral misoprostol vs. intravenous oxytocin in reducing blood loss after emergency cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calişkan E, Meydanli MM, Dilbaz B, Aykan B, Sonmezer M, Haberal A. Is rectal misoprostol really effective in the treatment of third stage of labor? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1038–45. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calişkan E, Dilbaz B, Meydanli MM, Ozturk N, Narin MA, Haberal A. Oral misoprostol for the third stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:921–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ozkaya O, Sezik M, Kaya H, Desdicioglu R, Dittrich R. Placebo-controlled randomized comparison of vaginal with rectal misoprostol in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2005;31:389–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Refaey H, Nooh R, O’Brien P, Abdalla M, Geary M, Walder J, et al. The misoprostol third stage of labour study: a randomised controlled comparison between orally administered misoprostol and standard management. BJOG. 2000;107:1104–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lokugamage AU, Paine M, Bassaw-Balroop K, Sullivan KR, Refaey HE, Rodeck CH. Active management of the third stage at caesarean section: a randomised controlled trial of misoprostol versus syntocinon. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:411–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2001.tb01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerstenfeld TS, Wing DA. Rectal misoprostol versus intravenous oxytocin for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:878–82. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, Lamberty N, White L, Richichi K. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000144119.94565.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, Carlan SJ, Richichi K. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gülmezoglu AM, Villar J, Ngoc NT, Piaggio G, Carroli G, Adetoro L, et al. WHO multicentre randomised trial of misoprostol in the management of the third stage of labour. Lancet. 2001;358:689–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lumbiganon P, Villar J, Piaggio G, Gulmezoglu AM, Adetoro L, Carroli G. Side effects of oral misoprostol during the first 24 hours after administration in the third stage of labour. BJOG. 2002;109:1222–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.t01-1-02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kundodyiwa TW, Majoko F, Rusakaniko S. Misoprostol versus oxytocin in the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75:235–41. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Epstein AE, Hallstrom AP, Rogers WJ, Liebson PR, Seals AA, Anderson JL, et al. Mortality following ventricular arrhythmia suppression by encainide, flecainide, and moricizine after myocardial infarction. The original design concept of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). JAMA. 1993;270:2451–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.20.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]