Abstract

Here, we report the case of a patient who sustained Nd: YAG laser macular injury with subsequent 6 year follow-up evaluation. A 23-year-old female was accidentally exposed to a Q-switched Nd: YAG laser without protective goggles. Upon initial evaluation, the best-corrected visual acuity of her affected eye was 20/100 OD. Fundoscopic examination revealed a macular laser burn and vitreous hemorrhage. Corticosteroids, in the form of 60 mg prednisolone, were administered orally with a 10 mg per week taper. Nineteen days following exposure, fundoscopic examination revealed a distinct epiretinal membrane which resolved within six months. The best-corrected visual acuity of the affected eye remained 20/100 OD. This clinical course is similar to those of previously reported cases including vitreous hemorrhage and subsequent epiretinal membrane formation. However, visual acuity did not recover despite spontaneous regression of the epiretinal membrane and at 6 year follow-up, there was neither choroidal neovascularization nor macular hole formation.

Keywords: Epiretinal membrane, Nd: YAG laser, Retinal injury, Vitreous hemorrhage

The increasing use of high-energy lasers in industry, research and medicine has resulted in accidental laser injuries to the retina.1-3 The growing use of the Nd:YAG laser augments the threat of accidental exposure. Here, we report a case of accidental exposure to a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with subsequent 6 year follow-up evaluation.

Case Report

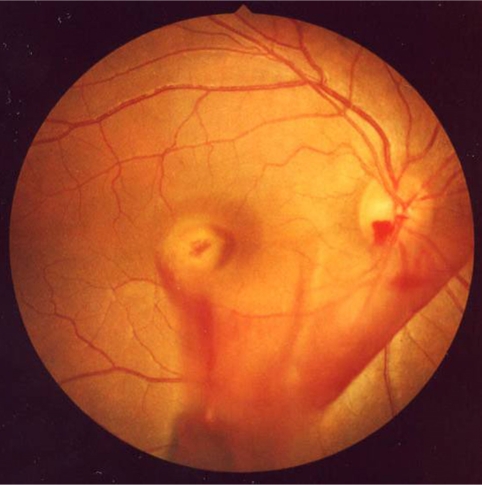

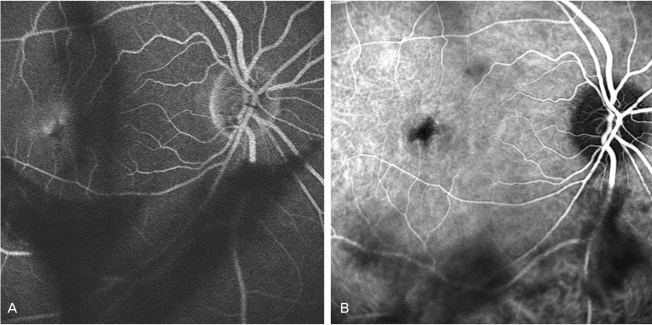

A 23-year-old female was accidentally exposed to a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser operating at 1064 nm in October 2002. The laser fired inadvertently while the patient was adjusting target without the use of her protective goggles. Immediately after the exposure, she experienced a bright flash of light followed by a sudden loss of vision in her right eye. Pulse duration and energy density were not assessed. Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/100 OD and 20/20 OS. The Amsler grid revealed metamorphopsia and central scotoma. Intraocular pressure and anterior segment biomicroscopy were unremarkable bilaterally. Fundoscopic examination of the right eye revealed a macular laser burn and vitreous hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Corticosteroids, in the form of 60 mg prednisolone, were administered orally with a 10 mg per week taper. The following day, her visual acuity remained 20/100 OD, and fluorescein angiography revealed a round area of hypofluorescence with early and late macular hyperfluorescence (Fig. 2a). Two days later, there was no hyperfluorescence on indocyanine green angiography (Fig. 2b).

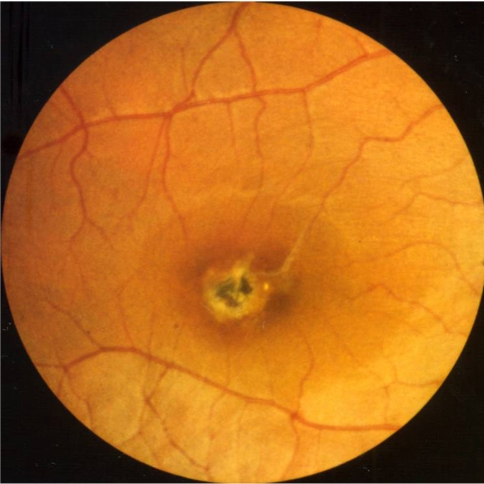

Fig. 1.

Fundoscopic photograph on the day of injury revealed vitreous hemorrhage and the site of laser injury at the macula.

Fig. 2.

(a) One day following the exposure, fluorescein angiography revealed a round area of hypofluorescence with late macular hyperfluorescence. (b) Two days later, indocyanine green angiography failed to demonstrate hyperfluorescence.

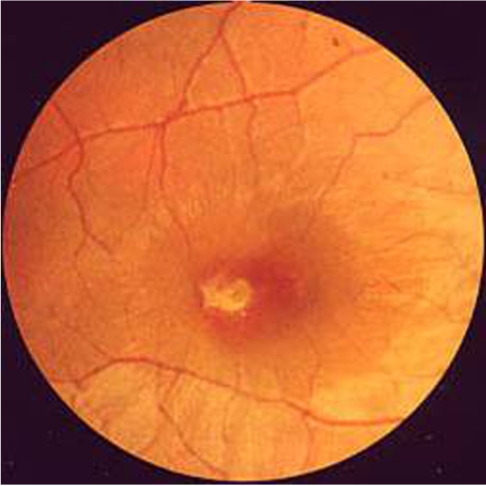

Nineteen days following the exposure, visual acuity remained at 20/100 OD and fundoscopic examination revealed a small amount of vitreous hemorrhage and a distinct epiretinal membrane (Fig. 3). Seven weeks later, the epiretinal membrane had extended and the retinal folds became more prominent, though there was no change in visual acuity. Six months later, the patient continued to have a visual acuity of 20/100 OD and fundoscopic examination at that time revealed spontaneous regression of the epiretinal membrane and a prominent chorioretinal scar with central pigmentation at the site of injury (Fig. 4). Visual acuity assessment and fundoscipic photography were performed at three month intervals, but did not reveal significant changes. Six years later, the patient's visual acuity remained at 20/100 OD and fundoscopic examination demonstrated the continued presence of a chorioretinal scar with more prominent central pigmentation compared to previous visits (Fig. 5). At six years follow-up, there was neither choroidal neovascularization nor macular hole formation.

Fig. 3.

Nineteen days following the exposure, fundoscopic photography revealed an epiretinal membrane with retinal folds radiating to the parafoveal area.

Fig. 4.

Six months later, fundoscopic photography revealed spontaneous regression of the epiretinal membrane and central pigmentation of the laser burn site.

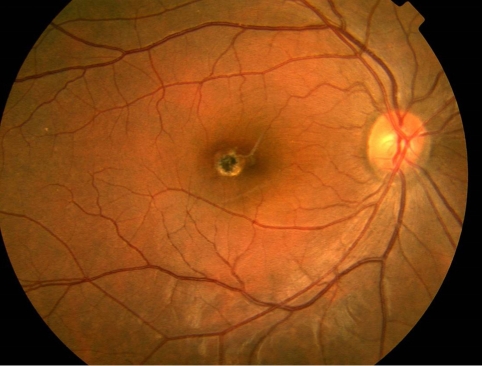

Fig. 5.

Six years later, fundoscopic photography revealed a chorioretinal scar with more prominent central pigmentation.

Discussion

Q-switched Nd:YAG laser injuries result in disruption of the choriocapillaris, Bruch's membrane, and the retinal pigment epithelium. The presence of subretinal and vitreous blood suggests that the major site of injury is the choriocapillaris. Previous cases of accidental Nd: YAG laser injuries include several common features such as retinal and vitreous hemorrhage.4,5

Here, we describe a case of Nd: YAG laser injury with six year follow-up. The exposure resulted in the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, which likely acts as a stimulant for fibroglial proliferation, resulting in an epiretinal membrane. The ensuing retinopathy is based on the development of a contractile membrane on either the internal or external surface of the retina. In the present case, the membrane formed externally. A previous report described the presence of striae resulting from contraction of the laser scar in lieu of a membrane.3 At 20 months follow-up, our patient demonstrated spontaneous regression of the epiretinal membrane by slit lamp ophthalmoscopy using a 78D lens rather than by optical coherence tomography. In contrast to previously reported cases,4-7 the best corrected visual acuity failed to recover, even after spontaneous resolution of the epiretinal membrane. In addition, the patient did not experience macular hole or cyst formation, though they are common findings in Nd: YAG laser injuries.4-7 Furthermore, we were unable to identify any choroidal neovascularization within the 6 year follow-up period, which is known to occur by intense laser photocoagulation breaking the retinal pigment epithelium-Bruch's membrane-choroid complex.8

A systemic corticosteroid was administered orally in an attempt to decrease the extent of injury by reducing the cellular response. Corticosteroids remain the most widely employed treatment for laser injuries.9

Laser devices are playing an increasingly large role in modern industry, research and medicine. This has led to a concomitant increase in laser-induced injuries, particularly ocular injuries as energy focuses on the retina. Gabel et al.10 have reported cases of unnoticed laser burns on routine eye examination in workers using laser devices. Further research is required to better define the mechanisms of tissue damage and improve existing therapy and protection to meet the demands of the increasing threat due to expanding laser application.

References

- 1.Boldrey EE, Little HL, Flocks M, Vassiliadis A. Retinal injury due to industrial laser burns. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)35068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearney JJ, Cohen HB, Stuck BE, et al. Laser injury to multiple retinal foci. Lasers Surg Med. 1987;7:499–502. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900070611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glovinsky Y, Regenbogen L, Bartov E, et al. Macular pucker following accidental laser burn. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol. 1982;6:355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thach AB, Lopez PF, Snady-McCoy LC, et al. Accidental Nd: YAG laser injuries to the macula. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:767–773. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam TT, Tso MO. Retinal injury by neodymium: YAG laser. Retina. 1996;16:42–46. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray S, Topping T, Young LH. Spontaneous peeling of epiretinal membrane associated with Nd:YAG laser injury. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asano T. Accidental YAG laser burn. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:116–117. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan SJ. Subretinal neovascularization. Natural history of an experimental model. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1804–1809. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040784015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe JA. Laser retinal injury. Mil Med. 1985;150:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabel VP, Birngruber R, Lorenz B, Lang GK. Clinical observations of six cases of laser injury to the eye. Health Phys. 1989;56:705–710. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198905000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]