Abstract

Purpose

Postoperative endophthalmitis is a dreaded outcome of any intraocular surgery. Fungal endophthalmitis is a particularly severe complication that poses a significant threat of blindness. We experienced seven consecutive cases of postoperative fungal endophthalmitis stemming from a single local clinic in which extensive early intervention resulted in favorable final visual acuity.

Methods

The present study is retrospective observational case series of fungal endophthalmitis. The initial case, as diagnosed by fungal culture, resulted in blindness. In the ensuing eight months, seven consecutive cases were referred to our institution. All were presumed to be fungal endophthalmitis as the cases possessed similar inflammatory findings to the preceding case and occurred in the same environment. Extensive surgical and antifungal treatment was immediately administered, including complete vitrectomy with removal of the intraocular lens and lens capsule and Amphotericin B injections.

Results

Retinal infiltration was identified in three cases and the lesion site was photocoagulated with an endolaser. All cases were confirmed fungal endophthalmitis by culture (4 cases: Candida parapsilosis, one case each: Fusarium, Acremonium, Candida tropicalis) and five cases required secondary intraocular lens implantation. Final corrected visual acuity ranged from 20/20 to 40/200 by the Snellen chart.

Conclusions

Early extensive surgical intervention and antifungal agent administration may result in favorable visual outcomes in patients with fungal endophthalmitis following cataract surgery.

Keywords: Cataract, Endophthalmitis, Fungal, Postoperative, Vitrectomy

Cataract surgery is the most common procedure in the field of ophthalmology and in the majority of local ophthalmologic clinics. There are many potential postoperative complications, the most serious of which is endophthalmitis.1 The incidence of bacterial endophthalmitis was 0.57%2 in the largest published series prior to 1973. Recently, the incidence was reported to be as low as 0.048%3 in the experience of New Zealand ophthalmologists. While bacterial endophthalmitis is a treatable complication given appropriate medical and surgical intervention, postoperative fungal endophthalmitis is a rare complication that frequently carries a worse prognosis.4-6

A 76 year-old woman was referred from a local ophthalmologic clinic for suspected delayed onset postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis following cataract and intraocular lens implantation three months prior to referral. Outside medical records indicated that she had sustained iritis and that while the intraocular inflammation had been partially treated with antibiotics and steroid therapy (i.e. topical and subconjuntival triamcinolone injections), vision was decreased to hand movement only in her right eye. Upon referral, the eye showed signs of anterior uveitis, thick white precipitation on the intraocular lens and severe vitreous opacification. Intraocular lens removal, anterior vitrectomy and an intravitreal Vancomycin injection were administered the following day. Fungal culture revealed growth of Candida parapsilosis and systemic and topical Amphotericin B were subsequently administrated. Inflammation resolved within three months but later recurred, resulting in phthisis with total retinal detachment. The seven consecutive cases resembling the initial case had also been seen at the vitreoretinal section of our department within the local clinic. The authors presumed that all cases were secondary to fungal endophthalmitis as they presented with similar inflammatory findings to the preceding case and stemmed from the same environment. Extensive surgical and medical treatment was administered and favorable results occurred during the two-year follow-up period.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a retrospective observational case series of fungal endophthalmitis occurring within our institution after experiencing a preceding case of postoperative endophthalmitis which resulted in blindness. Extensive surgical intervention included complete vitrectomy and removal of the intraocular lens and capsule. All cases were eventually confirmed by fungal culture. Final corrected visual acuity and postoperative complications were evaluated over a period of greater than two years follow-up.

Three males and four females with ages ranging from the 5th to 9th decade (mean; 71.0 years), with no significant systemic disorders or eye pathology other than senile cataracts were included in this study. All patients demonstrated mild immediate postoperative inflammation, but experienced inflammatory relapse several times during the ensuing one to two months despite treatment with systemic and topical steroids. All received several subconjuntival triamcinolone injections but were ultimately referred for failure of inflammatory resolution.

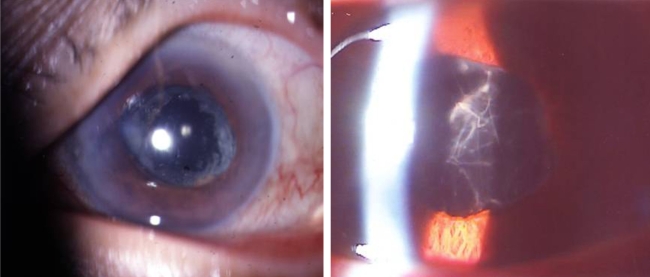

On physical examination all seven cases presented with the same ocular findings. Conjunctivae were injected and inflammatory cells filled the anterior chamber. Whitish inflammatory material was attached to the periphery of the intraocular lens and lens capsule (Fig. 1). The fundus was blurred due to vitreous inflammation and ultrasonography revealed vitreous opacification (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative findings of the anterior segment showed whitish inflammatory material around the intraocular lens (Left), and vitreous opacity and inflammatory materials throughout the entire vitreous (Right).

Within 24-48 hours, all seven patients underwent extensive surgery. In order to eliminate the inflammatory reservoir, the lens cortical remnant and lens capsule were removed thoroughly and a complete pars plana vitrectomy including vitreous base with scleral depression were performed. Operative findings revealed discrete, thick whitish inflammatory materials around the posterior lens capsule and vitreous base. Multiple fluff balls were observed in the vitreous in all cases and retinal infiltration was detected in four cases with subsequent laser photocoagulation for retinal-pigment epithelium attachment stabilization. Any remaining triamcinolone was removed as thoroughly as possible.

During the vitrectomy, 1 mg of Amphotericin B was mixed with 500 ml of irrigation solution (Balanced Salt Solution, BSS plus) to comprise a vitreous concentration of 10 µ/5 ml. Cases 1, 2, 5 and 6 received intravitreal Amphotericin B injections postoperatively because the inflammatory cells in the vitreous had increased and the fundi were again blurred. Case 2 demonstrated persistent inflammation following the second intravitreal injection and thus vitreous cavity irrigation and Amphotericin B injection were performed a third time (Table 1). All patients received postoperative oral itraconazole until the inflammation subsided.

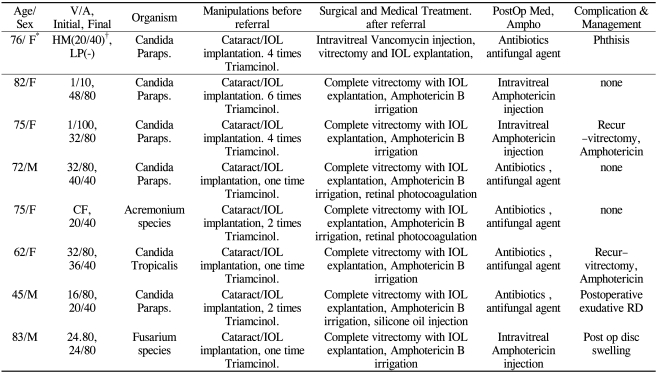

Table 1.

Preoperative findings, surgical treatment before and after referral, identified fungal organisms and complications in the initial case and seven consecutive cases

IOL=intraocular lens; FC=finger count; HM=Hand movement; Paraps=Parapsilosis; Triamcinol.=subconjunctival triamcinolone injection.

*Initial case; †best visual acuity in the middle of medical treatment of initial case.

Results

The final corrected visual acuity in this series ranged from 20/20 to 40/200 on the Snellen chart. Five cases showed 20/40 or better while other two attained acuity of 60/200 and 40/200. The anterior segment of all patients was clear and fundoscopic findings were clear or revealed photocoagulation spots in some. Three cases demonstrated increased inflammation and decreased vision after the corrective surgery and required repeat vitrectomy and intraocular Amphotericin B injection. Any inflammatory materials attached to the peripheral retina and ciliary body were removed using scleral depression (Table 1).

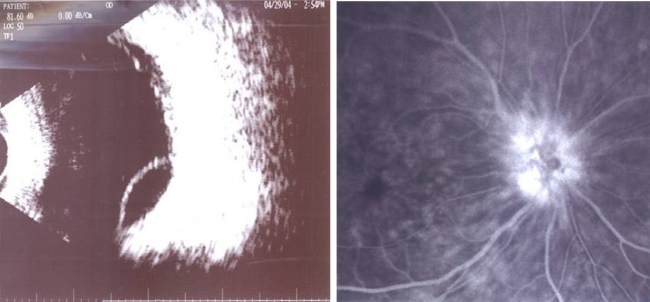

Bullous retinal detachment with vitreous haze developed in case 6 (Fig. 2). Upon secondary operation, scleral infiltration was found on the sclerotomy site and the authors were unable to identify any retinal tear. The detachment may have been exudative retinal detachment due to subretinal involvement. Internal drainage and silicone oil injection were performed to remove the remaining inflammatory dead space. One patient had optic disc involvement that persisted for two years during the follow-up period. Fluorescein angiography revealed hyperfluorescence of the disc (Fig. 2) that failed to improve with steroid pulse therapy, ultimately resulting in a final visual acuity of 60/200 on the Snellen chart. Five cases required secondary intraocular lens implantation after a lack of inflammatory signs for over six months. The other two patients refused secondary implantation.

Fig. 2.

Following vitrectomy in case 6, bullous retinal detachment and vitreous inflammatory materials were seen on ocular ultrasound (Left). Fluorescent leaking surrounding the disc appeared on fluorescein angiography in case 7 (Right).

Fungal culture of the vitreous sampled during vitrectomy was positive in all seven cases. In the initial case, the culture grew Candida parapsilosis. Four cases (Cases 1, 2, 3, 6) also grew Candida parapsilosis while the other three grew Acremonium species, Candida tropicalis and Fusarium species respectively.

Discussion

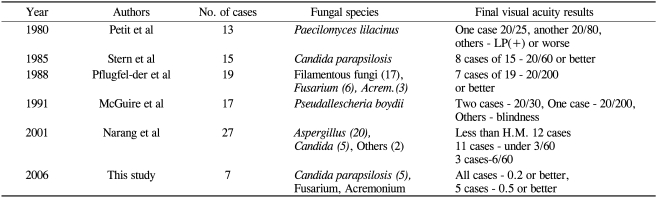

Previously published reports of postoperative fungal endophthalmitis have suggested that it results in poor visual prognosis and the majority of these cases report final visual acuity ranging from 20/200 to light perception (Table 2). The most favorable reported results until the present study were of 15 consecutive cases of Candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis by Stern et al.7 in 1985. In the report, only eight patients were left with visual acuity of 20/60 or better. Pflugfelder et al.6 reported 19 cases of exogenous fungal endophthalmitis wherein only seven cases showed a final visual acuity over 20/200 despite performing vitrectomy and intraocular Amphotericin B injections. Recently, Narang et al.8 reported 27 cases of fungal endophthalmitis that resulted in severe visual loss in 19 patients (70%). Compared to the aforementioned results, this study showed that all patients had 16/80 or better and five of seven cases had better than 20/40 visual acuity on the Snellen chart.

Table 2.

Other reported results of cases series involving fungal endophthalmitis

In the present study, the initial visual acuity ranged from finger count to 32/80 on the Snellen chart. In the initial case, visual acuity prior to cataract surgery had been hand movement only and improved to 20/40 in the middle of treatment. Unfortunately, however visual acuity ultimately declined to negative light perception. Therefore, the decision was made to perform extensive treatment despite the initial visual acuity of 32/80.

The conventional treatment for exogenous fungal endophthalmitis is intravitreal injection of an antifungal agent and vitrectomy. However, this protocol may not result in satisfactory visual acuity. The reason for poor visual prognosis may be that the vitreous serves as a fungus media and there are dead-spaces, including the intraocular lens and lens capsular bag, where antifungal agents cannot penetrate. We suggest that the incomplete vitrectomy left residual vitreous base allowing fungal growth. Another possible disadvantage with incomplete vitrectomy is in preserving the intraocular lens, which may allow the capsular bag to serve as in impenetrable dead-space to antifungal agents. Lastly, the fungal toxins may persist after conventional vitrectomy.

After experiencing the initial case of fungal endophthalmitis that resulted in blindness and phthisis despite improvement in visual acuity to 20/40 in the middle of treatment, we were able to assume that the seven subsequent cases were also due to fungal endophthalmitis prior to receiving the results of fungal stain and culture. The decision was then made to perform urgent extensive vitrectomy and antifungal therapy. It was hoped that extensive vitrectomy, including intraocular lens and lens capsule removal, would salvage visual acuity. Vitreous and inflammatory materials were removed completely through the vitreous base and pars plicata area using scleral depression. All seven cases except the initial case demonstrated 0.2 or more as the final corrected visual acuity. Moreover, there was no recurrence of endophthalmitis during the greater than 2 year follow-up period. Two cases had a final visual acuity of 0.3 and 0.2 on the Snellen chart. The causes of low vision were persistent granular keratic precipitates on the corneal center and chronic papillitis, respectively. During vitrectomy, four cases of retinal infiltration were identified; however, visual acuity improved all cases due to the lack of direct macular involvement.

Antifungal agents such as Amphotericin B have been proven safe for intravitreal injection.9 In the present study, we used intravitreal Amphotericin B mixed with anirrigating solution (1 mg/500 ml) during vitrectomy. Postoperative oral itraconzole was administered according to a previous report.10

As a post-vitrectomy complication, exudative retinal detachment occurred in case 4. Suspicion was high for retinal tear when bullous retinal detachment and a mildly hazy fundus examination were found, though none was ever identified. The patient received subretinal fluid aspiration and silicon oil injection and retinal elevation did not recur. Scleral infiltration was found in the site of previous sclerotomy in one case and the patient received silicon oil removal and secondary intraocular lens implantation. In this case, fungal exotoxin may have caused exudative retinal detachment.

Postoperative fungal endophthalmitis primarily develops in healthy, immunocompetent individuals. In this study, all patients were free from the immunocompromised state and lacked any significant chronic systemic disorder. All patients had received several subconjuntival triamcinolone injections at the local clinic prior to referral. We removed any remaining subconjunctival tramcinolone as thoroughly as possible. Coats et al.11 asserted that there is no evidence that the addition of corticosteroids impairs antifungal activity or enhances fungal proliferation in the rabbit model. Another report stated that intravitreal steroids may be beneficial in promoting faster clearance of inflammation in fungal endophthalmitis.12 In addition, corticosteroids are a well-known powerful anti-inflammatory agent. Therefore, the triamcinolone administered in the local clinics prior to referral may have played a role in reducing inflammation and preventing further retinal involvement.

Fungal culture was performed with vitreous and aqueous aspirated prior to the vitrectomy. Candida parapsilosis was cultured in the initial case as well as four subsequent cases. The other three cases demonstrated Candida tropicalis, Acremonium species and Fusarium species. All patients, including the initial case, likely had positive fungal cultures as no antifungal agent had been administered prior to complete vitrectomy.

In conclusion, complete vitrectomy including the vitreous base, removal of the intraocular lens and capsule, elimination of inflammatory materials in front of the ciliary body, with the addition of intravitreal antifungal injection and intraoperative irrigation may result in good visual prognosis incases of postoperative fungal endophthalmitis.

Footnotes

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2007.

Presented at the 93rd academy of Korean Ophthalmologic Society; April 9th, 2005; Busan, Korea.

References

- 1.Allen HF, Mangiaracine AB. Bacterial endophthalmitis after cataract surgery; Incidence in 36,000 consecutive operations with special reference to preoperative topical antibiotics. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:3–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1974.03900060007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirsty NE, Lall P. Postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: Effects of subconjuntival antibiotics and other factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;90:361–366. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000050363005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joondeph BC, Blanc JP, Polkjnghorne PJ. Endophthalmitis after pars plana vitrectomy: A New Zealand experience. Retina. 2005;25:587–589. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettit TH, Olson RJ, foos RY, Martin WJ. Fungal endophthalmitis following intraocular lens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:1025–1039. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020031015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire TW, Bullock JD, Bullock JD, Jr, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis; An experimental study with a Review of 17 human ocular cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1289–1296. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080090115034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pflugfelder SC, Flynn HW, Jr, Zwickey TA, et al. Exogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern WH, Tamura E, Jacobs RA, et al. Epidemic Postsurgical Candida Prapsilosis Endophthalmitis: Clinical Findings and Management of 15 consecutive cases. Ophthalmolgy. 1985;92:1701–1709. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narang S, Gupta A, Gupta V, et al. A Fungal endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: clinical presentation, microbiological spectrum, and outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:609–617. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang K, Peyman GA, McGetrick J. Vitrectomy in experimental endophthalmitis: Part I-Fungal infection. Ophthalmic Surg. 1979;10:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres Pérez JD, Olea Cascón J, Crespo Ortiz P, et al. Oral itraconazole for treatment of a candida parapsilosis endophthalmitis case. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2004;9:181–184. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912004000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coats ML, Peyman GA. Intravitreal corticosteroids in the treatment of exogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Retina. 1992;12:46–51. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majji AB, Jalali S, Das T, Gopinathan U. Role of intravitreal dexamethasone in exogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Eye. 1999;13:60–65. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]