Abstract

Calmodulin binds to IQ motifs in the α1 subunit of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2, but the affinities of calmodulin for the motif and for Ca2+ are higher when bound to CaV1.2 IQ. The CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ sequences differ by four amino acids. We determined the structure of calmodulin bound to CaV1.1 IQ and compared it with that of calmodulin bound to CaV1.2 IQ. Four methionines in Ca2+-calmodulin form a hydrophobic binding pocket for the peptide, but only one of the four nonconserved amino acids (His-1532 of CaV1.1 and Tyr-1675 of CaV1.2) contacts this calmodulin pocket. However, Tyr-1675 in CaV1.2 contributes only modestly to the higher affinity of this peptide for calmodulin; the other three amino acids in CaV1.2 contribute significantly to the difference in the Ca2+ affinity of the bound calmodulin despite having no direct contact with calmodulin. Those residues appear to allow an interaction with calmodulin with one lobe Ca2+-bound and one lobe Ca2+-free. Our data also provide evidence for lobe-lobe interactions in calmodulin bound to CaV1.2.

The complexity of eukaryotic Ca2+ signaling arises from the ability of cells to respond differently to Ca2+ signals that vary in amplitude, duration, and location. A variety of mechanisms decode these signals to drive the appropriate physiological responses. The Ca2+ sensor for many of these physiological responses is the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin (CaM).2 The primary sequence of CaM is tightly conserved in all eukaryotes, yet it binds and regulates a broad set of target proteins in response to Ca2+ binding. CaM has two domains that bind Ca2+ as follows: an amino-terminal domain (N-lobe) and a carboxyl-terminal domain (C-lobe) joined via a flexible α-helix. Each lobe of CaM binds two Ca2+ ions, and binding within each lobe is highly cooperative. The two lobes of CaM, however, have distinct Ca2+ binding properties; the C-lobe has higher Ca2+ affinity because of a slower rate of dissociation, whereas the N-lobe has weaker Ca2+ affinity and faster kinetics (1). CaM can also bind to some target proteins in both the presence and absence of Ca2+, and the preassociation of CaM in low Ca2+ modulates the apparent Ca2+ affinity of both the amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal lobes. Differences in the Ca2+ binding properties of the lobes and in the interaction sites of the amino- and carboxyl-terminal lobes enable CaM to decode local versus global Ca2+ signals (2).

Even though CaM is highly conserved, CaM target (or recognition) sites are quite heterogeneous. The ability of CaM to bind to very different targets is at least partially due to its flexibility, which allows it to assume different conformations when bound to different targets. CaM also binds to various targets in distinct Ca2+ saturation states as follows: Ca2+-free (3), Ca2+ bound to only one of the two lobes, or fully Ca2+-bound (4–7). In addition, CaM may bind with both lobes bound to a target (5, 6) or with only a single lobe engaged (8). If a target site can bind multiple conformers of CaM, CaM may undergo several transitions that depend on Ca2+ concentration, thereby tuning the functional response. Identification of stable intermediate states of CaM bound to individual targets will help to elucidate the steps involved in this fine-tuned control.

Both CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 belong to the L-type family of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, which bind apoCaM and Ca2+-CaM at carboxyl-terminal recognition sites in their α1 subunits (9–14). Ca2+ binding to CaM, bound to CaV1.2 produces Ca2+-dependent facilitation (CDF) (14). Whether CaV1.1 undergoes CDF is not known. However, both CaV1.2 and CaV1.1 undergo Ca2+- and CaM-dependent inactivation (CDI) (14, 15). CaV1.1 CDI is slower and more sensitive to buffering by 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid than CaV1.2 CDI (15). Ca2+ buffers are thought to influence CDI and/or CDF in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels by competing with CaM for Ca2+ (16).

The conformation of the carboxyl terminus of the α1 subunit is critical for channel function and has been proposed to regulate the gating machinery of the channel (17, 18). Several interactions of this region include intramolecular contacts with the pore inactivation machinery and intermolecular contacts with CaM kinase II and ryanodine receptors (17, 19–22). Ca2+ regulation of CaV1.2 may involve several motifs within this highly conserved region, including an EF hand motif and three contiguous CaM-binding sequences (10, 12). ApoCaM and Ca2+-CaM-binding sites appear to overlap at the site designated as the “IQ motif” (9, 12, 13), which are critical for channel function at the molecular and cellular level (14, 23).

Differences in the rate at which 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid affects CDI of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 could reflect differences in their interactions with CaM. In this study we describe the differences in CaM interactions with the IQ motifs of the CaV1.1 and the CaV1.2 channels in terms of crystal structure, CaM affinity, and Ca2+ binding to CaM. We find the structures of Ca2+-CaM-IQ complexes are similar except for a single amino acid change in the peptide that contributes to its affinity for CaM. We also find that the other three amino acids that differ in CaV1.2 and CaV1.1 contribute to the ability of CaV1.2 to bind a partially Ca2+-saturated form of CaM.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All peptides used were either synthesized in the core facility at the Baylor College of Medicine under the direction of Dr. Richard Cook or by GenScript Corp. (Piscataway, NJ). CaV1.1 IQB and CaV1.2 IQB peptides had a six-carbon biotin linker attached via an additional modified lysine at the carboxyl terminus of the peptide (CPC Scientific Inc., San Jose, CA). Calibrated Ca2+ buffers were ordered through Invitrogen. High grade reagents for crystallization experiments were purchased from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA) or from Sigma. N-Trimethoxysilylpropyl-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride for silylizing glassware was purchased through United Chemical Technologies (Bristol, PA).

Mutant CaM Constructs

Fluorescent recombinant mammalian CaM constructs (F19W, F92W, and F92W/E12Q) were prepared as described previously (1, 24). Constructs for the mammalian Ca2+-binding mutants E12QCaM and E34QCaM were also made previously (13). To prepare F19W/E34Q, we used a DNA construct for F19W in the pET3a vector. The cDNA primers (41 bp) were designed to introduce a glutamine substitution for a glutamate in the −z position of EF hands 3 and 4 (residues Glu-104 and Glu-140) by PCR site-directed mutagenesis. F19W/E12Q and F92W/E34Q were made similarly. Other mutants created using similar procedures included the following: 1) CaM mutants with cysteine mutations in the N-lobe (T34C) and the C-lobe (T110C); 2) E12Q/T34C/T110C; and 3) E34Q/T34C/T110C. The cDNA sequences were verified at the DNA Sequencing Core Facility at the Baylor College of Medicine. Protein expression and purification of these mutants were previously described (25).

Preparation of Recombinant CaMs

Recombinant mammalian CaM protein (CaM wild type, F19W, F92W, and T34C/T110C) was purified for fluorescence analysis as described previously (26), except dithiothreitol (20 mm) and EGTA (2 mm) were included in lysis buffer for cysteine mutants, and 5 mm dithiothreitol was kept throughout purification steps. Ca2+-binding mutants of CaM (T34C/T110C/E34Q and F19W/E34Q) were purified using a modified protocol from Rodney et al. (27).

Structure Determination

The complex of CaM-CaV1.1 IQ peptide complex was purified following the procedure described for the CaM-CaV1.2 IQ peptide complex (28). The complex was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in a buffer containing 20 mm MOPS, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 10 mm CaCl2. Crystals were grown by vapor diffusion by mixing 2 μl of complex into a 4-μl drop of a milieu from the well containing 32% polyethylene glycol 3500, 50 mm Tris, 50 mm MgCl2. Large football-shaped crystals grew to full size in 2 weeks in a Torrey Pines Scientific incubator (San Marcos, CA) at 20 °C. Data were collected at the Center for Advanced Microstructures and Devices Gulf Coast Protein Crystallography Consortium beamline at the Louisiana State University Center for Advanced Microstructures and Devices (Baton Rouge, LA). The HKL2000 software package was used for data set reduction (29). The structure of CaM/CaV1.1 IQ was determined by the molecular replacement method (30) using the CaM/CaV1.2 IQ structure (PDB code 2f3y) (28) as the search model. The parameters used for solving the crystal structure are presented in Table 1. Structure refinement and analyses were performed using CNS (31) and the CHAIN graphics program (32). The structure was deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the PDB code 2vay.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for X-ray crystal structure

| Data collectiona | CaM/CaV1.1 IQ peptide |

| Wavelength | 1.38079 Å |

| Maximum resolution | 1.94 Å |

| Highest shell | 2.06–1.94 Å |

| Total reflections | 49,660 |

| Unique reflections | 15,915 |

| Redundancyb | 2.0 (1.7) |

| Completenessb | 89.9% (51.0%) |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉b | 3.65 |

| Rsymb,c | 0.03 (0.205) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Rcryst/Rfreed | 0.228/0.285 |

| Protein atoms/Ca2+ | 1348/4 |

| Water molecules | 123 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal bond/angle | 0.0096 Å/1.277° |

a Crystal belongs to the C2 space group with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The native domain crystal has unit cell dimensions of a = 84.92 Å, b = 34.67 Å, c = 62.98 Å, and α = 90°, β = 113.69, γ = 90°.

b Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell.

c Rsym = Σhkl|Ihkl − 〈 Ihkl〉|/ΣhklIhkl.

d R-factor = Σhkl‖Fo| − |Fc‖/Σhkl|Fo|, where |Fo| and |Fc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes for reflection hkl. Rfree was calculated with a 10% subset of randomly chosen reflections not included in any stage of the refinement.

Determination of Affinity of CaM, E12QCaM, and E34QCaM for Peptides

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) with a Biacore3000 instrument (GE Biacore, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) was used to assess the affinity of CaM, E12QCaM, and E34QCaM for the biotinylated wild type and mutant IQ peptides (Table 2). Sensor chip SA was conditioned according to the manufacturer's protocol, and biotinylated wild type or mutant IQ peptides were immobilized to a sensor chip SA by loading 100 μl of 3 nm peptide in running buffer containing 3 mm CaCl2, 30 mm MOPS, 100 mm KCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 0.005% Tween 20, 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.5, at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. Biotin (5–10 μl of 300 nm) alone was immobilized to control flow cells on the chip and used to subtract bulk movement of CaM, the analyte, to the chip during binding. Peptide immobilization was preceded and followed by a system desorb. CaM, E12QCaM, and E34QCaM were injected at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. All experiments were performed in triplicate; each sensorgram representing an independent dilution. KD values were determined by fitting the amplitudes of the plateau phase as a function of CaM concentration using a one- or two-site saturation model.

TABLE 2.

Synthetic peptide sequences

Boldface is used for the amino acid that differs between the CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ peptides.

| Accession no. | α1 subunit | Sequence no. | Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q13936 | CaV1.2 | 1665–1685 | CaV1.2 IQ | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFKKRKEQ |

| Q13698 | CaV1.1 | 1522–1542 | CaV1.1 IQ | KFYATFLIQEHFRKFMKRQEE |

| Mutant | CaV1.2 | CaV1.2 Y1675H | KFYATFLIQEHFRKFKKRKEQ | |

| Mutant | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1 H1532Y | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFMKRQEE | |

| Mutant | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFKKRQEE | |

| Mutant | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1/H1532Y/Q1540K | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFMKRKEE | |

| Mutant | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1/H1532Y/E1542Q | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFMKRQEQ | |

| Mutant | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFKKRKEE | |

| Biotinylated | CaV1.2 | CaV1.2 IQBa | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFKKRKEQK,-C6-biotin | |

| Biotinylated | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1 IQBa | KFYATFLIQEHFRKFMKRQEEK-C6-biotin | |

| Biotinylated | CaV1.2 | CaV1.2 Y1675H-IQBa | KFYATFLIQEHFRKFKKRKEQK-C6-biotin | |

| Biotinylated | CaV1.1 | CaV1.1 H1532Y-IQBa | KFYATFLIQEYFRKFMKRQEEK-C6-biotin |

a Modified lysine residue was inserted to attach linker for biotin tag.

Determination of Apparent Ca2+ Affinity of CaM Mutants with a Tryptophan Substitution

The procedure used was described by Black et al. (1). Data were fit by nonlinear regression analyses with either a standard dose-response curve or, if appropriate, a biphasic dose-response curve as modeled previously (1, 33).

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) of Labeled CaM

CaM with cysteine mutations at threonines 34 and 110 was purified and labeled with 5-((((2-iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino)naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (1,5-IAEDANS) and N- (4-dimethylamino-3,5-dinitrophenyl) maleimide (DDPM), according to Xiong et al. (25). Only CaMs labeled with both IAEDANS and DDPM demonstrate FRET (25).

For FRET measurements, 200 nm labeled CaM was incubated with 1 μm peptide for 1 h at room temperature in a 20 μm Ca2+ buffer from Molecular Probes (Ca2+ calibration buffer kit 3). Fluorescence was measured at 400–625 nm with an SLM8000 spectrofluorometer with 350 nm excitation. Settings included 8-nm bandpass excitation and emission slits, 309 nm cut-on excitation filter, 395 nm cut-on emission filter, and 1-s integration times. All spectra had the same spectral maximum near 493 nm, and bar graphs reflect the observations at this wavelength.

Ca2+ Dissociation Kinetics

Stopped-flow experiments were performed as described (1, 24) using an Applied Photophysics instrument (model SX.18MV; Leatherhead, UK) to measure rates of Ca2+ dissociation (koff) at 22 °C. Instrument parameters are the same as described (1). Represented data were averages of 5–8 individual traces fit with either a single or double exponential curve after premixing reached equilibrium. Tryptophan fluorescence was measured after rapidly mixing equal volumes (50 μl each) of solution A, F19WCaM or F92WCaM (4 μm), peptide (20 μm), and Ca2+ (200 μm) in 10 mm MOPS, 90 mm KCl, pH 7.0, with solution B, EGTA (10 mm). All traces were fit with the exponential Equation 1,

where A is the amplitude of the fluorescence change, and k is the rate at which the change is occurring.

Ca2+ dissociation rates (1) were also determined with Quin-2. Solution A (CaM (8 μm), IQ peptide (40 μm), Ca2+ (15 μm) in 10 mm MOPS, and 90 mm KCl, pH 7.0) was rapidly mixed with an equal volume of solution B, Quin-2 (150 μm). The reaction was monitored by exciting fluorescence at 330 nm and measuring light emission with 510-nm broad bandpass filter (Oriel) in place. Quin-2 fluorescence traces required fits with the double exponential Equation 2,

where A1 and A2 are component amplitudes of the fluorescence change, and k1 and k2 are the corresponding rates of change. The double exponential reflects the Ca2+ dissociation rates from both the N-lobe (fast) and the C-lobe (slow). The molar quantity of Ca2+ dissociating from CaM was calculated by monitoring the increase in Quin-2 fluorescence with increasing concentrations of Ca2+ standards (10, 20, 40, and 80 μm) (34).

RESULTS

Identification of IQ Residues That Interact Directly with Ca2+-CaM

To define the determinants for interaction of CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ (differing by four amino acids) with CaM, we obtained crystals of Ca2+-CaM bound to the CaV1.1 IQ peptide and determined the structure to 1.94 Å resolution (Table 1). The crystals are isomorphous to those formed with CaV1.2 IQ, and the crystal properties (Table 1) are very similar to those of the complex with CaV1.2 IQ peptide, but the CaM/CaV1.2 structure was determined at a higher resolution of 1.45 Å (28).

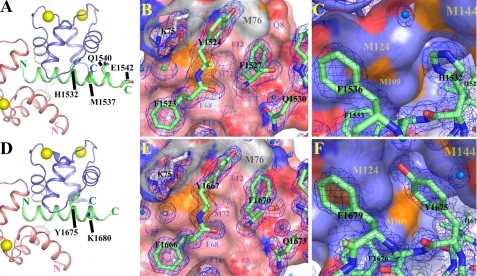

The N-lobe of CaM binds the amino terminus of the CaV1.1 IQ peptide, and the C-lobe binds the carboxyl terminus of CaV1.1 IQ in a parallel arrangement similar to that seen with CaV1.2 IQ (Fig. 1, A and D) and other IQ peptides (28, 35, 36). As expected from the identity of the amino-terminal portions of the CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ peptides, the N-lobe of CaM binds the amino-terminal peptide sequences in nearly identical conformations (Fig. 1, B and E). The root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) for the backbone atoms of the superimposed N-lobes is 0.34 Å. This value is about 2-fold smaller than the r.m.s.d. of 0.75 Å for the superimposed C-lobes, both of which are smaller than the overall backbone r.m.s.d. of 0.88 Å for the superimposed structures of the two CaM-peptide complexes. This indicates a difference in the relative orientation between the two lobes in the two structures.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of CaM bound to CaV1.1 IQ (PDB code 2vay) is represented in A–C. Structure of previously solved CaM bound to CaV1.2 IQ was obtained from the PDB with accession number 2f3y (d–F). Ribbon schematics represent CaM bound to CaV1.1 IQ in A or to CaV1.2 IQ in D. Peptides are represented as green ribbons. Ca2+ ions are represented as yellow spheres. The amino terminus (N) of the peptide contacts the N-lobe (pink ribbon) of CaM. C-lobe of CaM is blue. Linker ribbons that join the lobes of CaM are light gray. Residues of CaV1.1 IQ motif that are different from CaV1.2 IQ are represented as sticks on peptide ribbon, except for the residues not observed in the structure. B and E depict peptide stick residues contacting molecular surface of the N-lobe. C and F show peptide residue side chains (shown as sticks) in the vicinity of the C-lobe hydrophobic pocket formed by methionines (shown as molecular surface). B, C, E, and F, N-lobe carbons are pink, and carbon atoms in the linker between N- and C-lobes of CaM are light gray; C-lobe carbons are light blue (teal); peptide carbons are green; oxygen atoms are red; sulfur atoms are orange; nitrogen atoms are dark blue; waters are marine spheres; speculated chloride is green sphere. The 2Fo − Fc maps representing electron density are blue meshes. For best visibility, the 2vay 2Fo − Fc map is at 1.0 Å threshold and 2f3y map is at presented 0.5 Å.

Other differences are detected in the C-lobe interactions. There is a salt bridge between Arg-1539 on the CaV1.1 IQ peptide and Glu-127 of CaM that was not observed in our CaV1.2 IQ-CaM structure (28), but it was seen in the structure by Van Petegem et al. (36). Of the four nonconserved residues, only His-1532 on CaV1.1 IQ (Fig. 1, A and C) and Tyr-1675 in CaV1.2 IQ (Fig. 1, D and F) contact Ca2+-CaM. In Ca2+-CaM/CaV1.2 IQ, a water molecule forms hydrogen bonds both with the hydroxyl group side chain of the Tyr-1675 and with the carbonyl oxygen of the Met-124 main chain (28). A hydrophobic pocket formed by four C-lobe methionine side chains is more collapsed around His-1532 (Fig. 1C). This Ca2+-CaM methionine pocket expands around the bulkier Tyr-1675 on the CaV1.2 IQ peptide (Fig. 1F). Although the methionine side chains are slightly farther away from Tyr-1675, the α-carbon atoms are actually drawn inward toward the tyrosine. When comparing structures, the main chain α-carbon atoms of residues of Met-109, Met-124, Met-144, and Met-145 are displaced by 0.54, 0.18, 0.52, and 0.38 Å, respectively. The α-carbon to α-carbon distance from Met-109 to Met-145 is 0.41 Å closer in the presence of CaV1.2 IQ than in the presence of CaV1.1 IQ. The α-carbons are 0.12 Å closer from Met-124 to Met-144. The difference in α-carbon positions correlates with small perturbations in backbone structure. As mentioned above, the r.m.s.d. of the C-lobes from both complexes is 0.75 Å, but it is influenced mainly by the difference in the relative positions of the α6-α7 loops; the r.m.s.d. measured without the α6-α7 loop drops to 0.63 Å. Because 0.63 Å is still considerably larger than the r.m.s.d. of the N-lobes, it likely reflects variations in the C-lobe conformations caused by the different peptides.

Because the pH of the crystallization solution is 8.3, His-1532 of CaV1.1 IQ is likely in the neutral or nonprotonated form. A charged residue in this position is predicted to be unfavorable. To assess this, we created peptides with an H1532D replacement in CaV1.1 IQ. This peptide does not bind Ca2+-CaM (data not shown), suggesting that the residue in this position (His-1532 of CaV1.1 IQ or Tyr-1675 of CaV1.2 IQ) is important for the interactions within the methionine pocket. A useful side note is that the H1532D mutation in CaV1.1 can be used to abolish CaM binding.

How Nonconserved Amino Acids in IQ Motif Regulate the Affinity for Ca2+-CaM

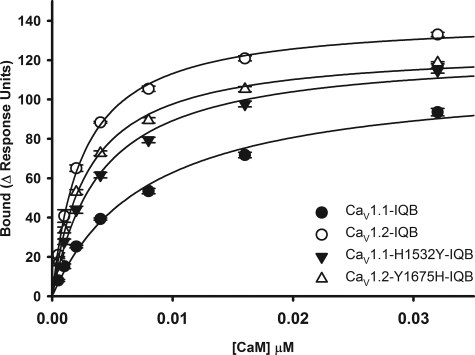

To address the question of how the four nonconserved amino acids affect the affinity of the IQ peptides for Ca2+-CaM, we synthesized the peptides shown in Table 2 and assessed their affinity using SPR. CaV1.1 IQ, CaV1.2 IQ, CaV1.2 Y1675H, CaV1.1 H1532Y, and four CaV1.1 mutant peptide with the H1532Y substitution and one or more amino acid changes were tested. Briefly, we assessed the affinity of the biotinylated wild type and mutant IQ peptides listed in Table 2 for Ca2+-CaM in saturating Ca2+ concentrations. We also performed competition experiments for CaM binding to immobilized biotinylated peptides using increasing concentrations of the nonbiotinylated peptides listed in Table 2 (see supporting information). Binding data reflecting the interaction of Ca2+-CaM with the biotinylated peptides are shown in Fig. 2. The interactions are adequately modeled with a simple bimolecular interaction for the concentration range shown in Fig. 2, with a KD of 7.9 nm for the CaV1.1 IQB, 2.5 nm for the CaV1.2 IQB, 4 nm for the CaV1.1 H1532Y-IQB, and 2.9 nm for the CaV1.2 Y1675H-IQB. This finding suggests that at low concentrations (<50 nm approximately) CaM assumes one binding conformation to the IQ peptides. As concentration increases, the data are fitted better to the two site saturation model (data not shown), suggesting that at higher concentrations CaM binds in two or more different conformations to the IQ peptides. For simplicity, we have chosen to compare only the high affinity interactions. The H1532Y mutation in CaV1.1 IQ increases the affinity for CaM, but the affinity is still lower than that of CaV1.2 IQ. The Y1675H mutation in CaV1.2 IQ results in only a decrease in CaM affinity. These findings together with the competition data with the other mutant peptides (see supporting information) suggest that all four amino acids that differ between the peptides contribute to the overall affinity for CaM, despite the finding that only one of them interacts with CaM in the crystal structure, suggesting that the interactions detected in the crystal are not the only interactions that occur in solution.

FIGURE 2.

Affinity of CaM for biotinylated wild type and mutant IQ peptides. CaM binding to peptides CaV1.1 IQB, CaV1.2 IQB, CaV1.1 H1532Y-IQB, and CaV1.2 Y1675H-IQB is shown. The solid lines represent the fits to one site saturation model. The KD values are 7.9 ± 1.1 nm for CaV1.1 IQ, 2.5 ± 0.1 nm for CaV1.2 IQ, 4.0 ± 0.4 nm for CaV1.1 H1532Y-IQB, and 2.9 ± 0.2 nm for CaV1.2 Y1675H-IQB. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

Amino Acids in the IQ Motif That Regulate the Ca2+ Affinity of Bound CaM

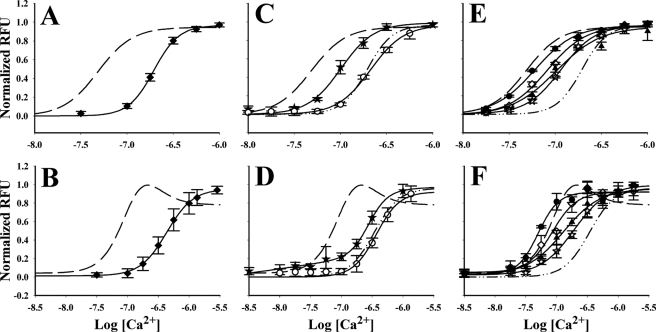

The primary function of CaM is to transduce a Ca2+ signal into a protein response. The apparent affinity of CaM for Ca2+ in the presence of a target peptide is coupled to the affinity of CaM for the peptide. In addition, an interaction of apoCaM (Ca2+-free CaM) with an IQ peptide can increase the apparent Ca2+ affinity of CaM by altering the conformation of the Ca2+-binding sites. Tryptophan mutants of CaM have been used to assess apparent Ca2+ affinity to CaM complexed to peptides (24). The apparent Ca2+ affinity of CaM, referred to here as KD,app, is determined from the Ca2+ titration of the tryptophan fluorescence. F19W is a CaM mutant that indirectly measures Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe, and the interaction of CaV1.2 IQ with F19W increases its Ca2+ affinity (1). The apparent Ca2+ affinity of the N-lobe of F19W complexed to CaV1.1 IQ (254 nm) is less than that of the N-lobe of F19W bound to CaV1.2 IQ (49 nm) (Fig. 3A and Table 3) (1). We used F92WCaM to assess Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe. The Ca2+ titration of the fluorescence of the C-lobe of F92W was fit with a single component for CaV1.1 but was distinctly biphasic with CaV1.2 (1), as characterized by a Ca2+-dependent increase followed by a decrease in fluorescence. The decrease in fluorescence with F92W/CaV1.2 IQ at higher Ca2+ concentrations is likely to be due to the N-lobe quenching the fluorescence of the C-lobe upon binding Ca2+. The discrepancy between the N-lobe Ca2+ affinity determined with CaV1.2 and F19W (49 nm) and that estimated from the quenching (198 nm) is likely to be due to the difficulty in fitting this complex biphasic curve. In these experiments the peptide is present in a 5-fold molar excess over CaM, and therefore, two CaMs binding to a single peptide is not likely. Overall, the Ca2+ affinity of the C-lobe of F92W complexed to CaV1.2 IQ is about 5-fold higher than that of the C-lobe of F92W bound to CaV1.1 IQ, a factor that is similar to the change observed at the N-lobe (Fig. 3B and Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Effect CaV1.1 IQ peptides on Ca2+ affinity of CaM mutants with tryptophan reporters. Normalized relative fluorescence units (RFU) from 1 μm tryptophan mutant CaM and 5 μm peptide are plotted as the mean ± S.D. from three independent trials. A, C, and E contain normalized fluorescence data for F19W; and B, D, and F contain data for F92W. In all panels, data describing Ca2+ binding to tryptophan mutant CaM complexed with CaV1.2 IQ peptide were presented before in Black et al. (1), but the fits from F19W/CaV1.2 IQ are represented by a dashed line in A, C, and E; or the fit from F92W/CaV1.2 IQ are represented by a dashed line in B, D, and F. A and B, CaM/CaV1.1 IQ, closed diamonds. C and D, closed star, CaM/CaV1.2 Y1675H; and open circles, CaM/CaV1.1 H1532Y. Dash-dot-dot trace represents the curve fitted CaM/CaV1.1 IQ in A and B for F19W and F92W, respectively. Data for F92W/CaV1.2 Y1675H were fit with a biphasic sigmoid curve. E and F, open diamond, CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K; closed triangle, CaV1.1/H1532Y/Q1540K; open star, CaV1.1/H1532Y/E1542Q; and closed circle, CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K. Dash-dot-dot traces for E and F are the same as in C and D, respectively.

TABLE 3.

CaM KD,app for Ca2+ in presence of peptides determined from analyses of fluorescence from CaM containing tryptophan substitutions

Superscript numbers 1–4 are used to mark the values that are compared through the p values that are given in the last two rows in table.

| F19W KD,app | Hill coefficient | F92W KD,app | Hill coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | |||

| No peptide | 4840 ± 700 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 1,400 ± 153 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| CaV1.1 IQ | 1254 ± 12 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 1540 ± 33 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| CaV1.2 IQ | 249 ± 3 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 104 ± 9 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 198 ± 51 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| CaV1.1 H1532Y | 3213 ± 11 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2400 ± 40 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| CaV1.2 Y1675H | 4104 ± 7 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 250 ± 20 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K | 82 ± 1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 384 ± 10 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/Q1540K | 102 ± 5 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 135 ± 22 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/E1542Q | 115 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 193 ± 26 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K | 60 ± 1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 450 ± 2 | 2.6 ± 0.7 |

| p value for 1–2, 2–4, 1–4 | <0.0003 | p value for 1–2 | 0.0003 | |

| p value for 1–3 | 0.01 | p value for 1–3, 1–4 | 0.0001 |

Identification of the Amino Acids Responsible for the Higher Ca2+ Affinity of CaM Bound to CaV1.2

As mentioned previously, of the four nonconserved amino acids, only His-1532 in CaV1.1 IQ and Tyr-1675 in CaV1.2 actually contact Ca2+-CaM in the crystal structures (Fig. 1). If the residue at this position in the IQ motifs is responsible for the difference in Ca2+ affinity of CaM bound to CaV1.2 versus CaV1.1, it should be possible to lower the Ca2+ affinity of CaV1.2 IQ by converting Tyr-1675 to a His and to increase the Ca2+ affinity of CaV1.1 IQ by converting His-1532 to a Tyr. The peptides with amino acids substitutions used in this study are listed in Table 2. The apparent N-lobe Ca2+ affinity of F19W bound to CaV1.1 H1532Y is only slightly different from that of F19W bound to CaV1.1 IQ, suggesting that this residue alone is not responsible for the higher Ca2+ affinity of the N-lobe of F19W bound to CaV1.2 IQ (Fig. 3C). The apparent N-lobe Ca2+ affinity of F19W bound to CaV1.2 Y1675H is less than that of F19W bound to CaV1.2 IQ, but it is still higher than that of F19W bound to CaV1.1 IQ. With F92W to monitor Ca2+ affinity of the C-lobe, the first obvious difference using CaV1.2 Y1675H is the absence of the fluorescence quenching seen at higher Ca2+ concentrations with CaV1.2 IQ and F92W (Fig. 3D). This suggests that the lobes may not be in close enough proximity when bound to the CaV1.2 Y1675H peptide to cause quenching. The Y1675H substitution does reduce the Ca2+ affinity of the C-lobe of the F92W (Fig. 3, B and D, and Table 3). These data suggest that the amino acids at this position influence the Ca2+ affinities of both lobes of CaM but cannot alone account for the difference in Ca2+ affinities of CaM bound to CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ. The other nonconserved amino acids, despite their lack of contact with Ca2+-CaM in the crystal structure, must be contributing to these observed differences.

Lys-1680, Lys-1683, and Gln-1685 provide CaV1.2 IQ with a +3 net charge compared with CaV1.1 IQ. Four peptides, each containing the H1532Y substitution in CaV1.1 and one or more of the above amino acid changes (Table 2), were tested for effects on the Ca2+ affinity of bound F19WCaM and F92WCaM. All of these peptides increased the apparent Ca2+ affinity of both F19W and F92W relative to these CaMs complexed to either CaV1.1 IQ or CaV1.1 H1532Y (highest p value = 0.0017) (Fig. 3, E and F, and Table 3). The most dramatic changes were seen with CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K and CaV1.1/.H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K. These data suggest that all of the nonconserved residues modulate the Ca2+ affinity of both lobes of CaM.

Partially Ca2+-saturated CaM Binds with Both Lobes to CaV1.2 IQ

One explanation of the observation that amino acids that do not interact with Ca2+-CaM in the crystal increase Ca2+ affinity is that these amino acids are involved in the binding of CaM in a Ca2+-free or a partially Ca2+-saturated state. This type of interaction could increase the apparent Ca2+ affinity of the sites by altering the conformation of the Ca2+-free sites. We used Ca2+-binding site mutants of CaM, FRET analyses, and measurement of Ca2+ dissociation rates to determine whether CaV1.2 and CaV1.1 have different abilities to bind CaM with one lobe Ca2+-bound and one lobe Ca2+-free.

To assess the effects of Ca2+ binding at one lobe of CaM on the Ca2+ binding properties of the second lobe, we created a series of CaM mutants (F19W/E34Q, F92W/E12Q, F19W/E12Q, and F92W/E34Q) that combined the tryptophan substitutions with mutations in either the N- or C-lobe Ca2+-binding sites. As shown previously with Drosophila CaM, the E12Q mutation (glutamates in the −z positions of EF hands 1 and 2 are mutated to glutamines) abolishes Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe, and the E34Q mutation (glutamates in the −z positions of EF hands 3 and 4 are mutated to glutamines) abolishes Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe (37). The F19W/E34Q and F92W/E12Q mutants are used to detect Ca2+ binding to the N- and C-lobes, respectively. Mutations in the Ca2+-binding sites in the C-lobe decreased the apparent Ca2+ affinity of the N-lobe, whereas mutations in the N-lobe had lesser effects on the apparent Ca2+ affinity of the C-lobe bound to CaV1.2 (Fig. 4A and Table 4). The apparent Ca2+ affinity of F19W/E34Q when bound to CaV1.2 IQ (KD,app for Ca2+ = 208 nm) is greater than when bound to CaV1.1 IQ (KD,app for Ca2+ = 690 nm) (Fig. 4A and Table 4). These values demonstrate lower affinities than obtained with F19WCaM complexed to CaV1.2 IQ (50 nm) and CaV1.1 IQ (190 nm) and are likely to reflect both the contributions of the other lobe and the decreased affinity of the Ca2+-binding site mutants of CaM for the peptide. The Ca2+ titration of the tryptophan fluorescence of F92W/E12Q CaM-CaV1.2 IQ is monophasic with increasing Ca2+ concentrations with a KD,app of 135 nm (Table 4) (1). F92W/E12Q complexed to CaV1.1 displays a KD,app for Ca2+ of 790 nm (Fig. 4B and Table 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of blocking Ca2+ binding to a single lobe on the KD,app of CaM for Ca2+ when bound to peptide. All data were collected in triplicate as the mean ± S.D. A, 1 μm F19W/E34Q alone (closed circles) or with 5 μm CaV1.1 IQ (open circles) or with 5 μm CaV1.2 IQ (closed diamonds). All data are fit with standard sigmoid curve. Long dashes, fit for F19W/CaV1.2 IQ shown previously (1); dash-dot-dot, fit for F19W/CaV1.1 IQ from Fig. 3. B, 1 μm F92W/E12Q alone (closed circles) or with 5 μm CaV1.1 IQ (open circles) are plotted. Long dashes, fit for F92W/CaV1.2 IQ shown previously (1); dash-dot-dot, fit for F92W/CaV1.1 IQ from Fig. 3; dotted line, fit for F92WE12Q/CaV1.2 IQ shown previously (1).

TABLE 4.

Effects of Ca2+-binding site mutations on the Ca2+ affinity of the lobes of CaM

NF indicates no fluorescence change.

| F19W/E34Q, KD,app | Hill no. | F92W/E12Q, KD,app | Hill no. | F19W/E12Q, KD,app | Hill no. | F92W/E34Q, KD,app | Hill no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+-binding lobe | N-lobe | C-lobe | C-lobe | N-lobe | ||||

| No peptide | 5400 ± 700 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1700 ± 500 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| CaV1.1 IQ | 690 ± 30 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 790 ± 70 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| CaV1.2 IQ | 208 ± 7a | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 135 ± 6 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 21 ± 10 | 2.0 ± 1 | 120 ± 42 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

ap value = 0.00001.

We used two additional mutants as follows: the F19W/E12Q to detect alterations in Ca2+ free N-lobe arising from Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe, and F92W/E34Q to detect alterations in Ca2+-free C-lobe arising from Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe. We were unable to detect Ca2+-dependent fluorescence changes with F19W/E12Q and F92W/E34Q either in the absence of peptide or with CaV1.1 IQ. However, we were able to detect Ca2+-dependent changes in fluorescence of both F19W/E12Q and F92W/E34Q in complex with CaV1.2 IQ. The KD,app for Ca2+ for F19W/E12QCaM-CaV1.2 IQ was 21 nm, whereas that of F19W/E12QCaM-CaV1.2 IQ was 120 nm. These findings suggest that Ca2+ binding to either the N- or C-lobe of CaM changes the environment of the tryptophan in the Ca2+-free lobe, suggesting an interaction between lobes when CaM is bound to CaV1.2. In both cases the apparent affinity was higher when the tryptophan was in the Ca2+-free lobe suggesting that a tryptophan in the Ca2+-free lobe either facilitates the interaction between the lobes or increases the affinity of the Ca2+-free lobe for CaV1.2. Either explanation would support a lobe-lobe interaction when CaM is bound to CaV1.2.

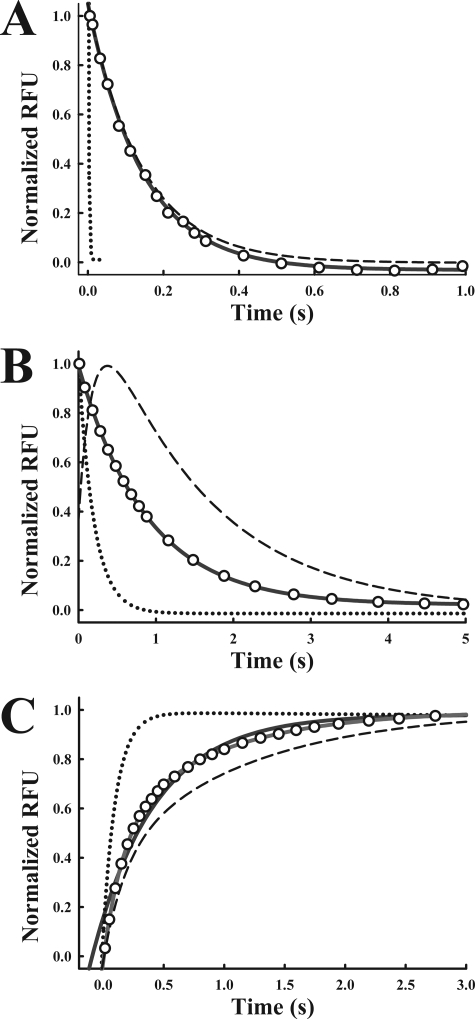

To further support the interaction of partially saturated CaM with CaV1.2, we used stopped-flow fluorescence measurements and the F19W and F92W mutants to measure the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from each lobe of CaM in the presence of the peptides. The tryptophan mutations in F19W and F92W have only small effects on Ca2+ dissociation rates compared with unmodified CaM (1). Similar experiments have previously shown that Ca2+ dissociates from the N-lobe faster than from the C-lobe of CaM and that the binding of CaM to peptides slows the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from both lobes (1). The interaction with CaV1.1 also slows Ca2+ dissociation from F19W and F92WCaM (Fig. 5). Using F19W we found that the rate of dissociation from the N-lobe was similar when F19W was bound to CaV1.1 IQ (6.3 s−1) and CaV1.2 IQ (6.4 s−1) (Fig. 5A and Table 5). Initial Ca2+ dissociation is modestly faster from the C-lobe (F92W) when bound to CaV1.1 IQ (kd = 1.3 s−1) compared with CaV1.2 IQ (0.8 s−1) (Fig. 5B and Table 5). However, F92W complexed to CaV1.2 IQ (but not CaV1.1 IQ) displays a two component dissociation (1). The fluorescence first increases and then decreases. These data demonstrate that the tryptophan in the F92WCaM-CaV1.2 IQ complex can detect a conformational change in the N-lobe as it releases Ca2+ and that a stable intermediate with CaM with its N-lobe Ca2+ free can be detected kinetically. It is possible that CaM also binds CaV1.1 IQ with one lobe Ca2+-free, but the biphasic dissociation is too fast to detect in these experiments.

FIGURE 5.

Ca2+ dissociation from CaM is faster when it is bound to CaV1.1 IQ peptide than when bound to CaV1.2 IQ. A, dotted line and dashed line represent fits to data that were published previously showing F19W alone and F19W/CaV1.2 IQ, respectively (1). New data showing Ca2+ dissociation from F19W bound to CaV1.1 IQ are represented by open circles. For clarity in comparing fits, only ∼5% of the total data points are plotted. Data are normalized to maximum and minimum fluorescence. Gray solid line represents a fit with a single exponential. B, dotted line and dashed line represent fits to data that were published previously showing F92W alone and F92W/CaV1.2 IQ, respectively (1). New data showing Ca2+ dissociation from F92W bound to CaV1.1 IQ are represented by open circles. Only ∼5% total data displayed for clarity in comparing fits. Gray solid line is single exponential fit. C, Quin-2 fluorescence increases as Ca2+ dissociates from CaM. Dotted line and dashed line are fits to data that were published previously showing CaM alone and CaM/CaV1.2 IQ, respectively (1). ∼5% of collected data for CaM in presence of CaV1.1 IQ peptide are shown as open circles. The gray solid line representing a single exponential fit does not fit as well as the black solid line representing a double exponential fit (Rsqr 0.9776, gray; 0.9999, black).

TABLE 5.

Ca2+ dissociation rates from CaM in presence of peptides

| Ca2+ dissociation rate via (CaM-Trp) mutants |

Ca2+ dissociation rate via Quin-2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F19W kd | F92W kd | kd1 | kd2 | |

| s−1 | s−1 | s−1 | s−1 | |

| No peptidea | 650 | 5.0 | >1000 | 7.5 |

| CaV1.1b | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| CaV1.2a,b | 6.4 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 0.9 |

| p valueb | 0.0036 | 0.0006 | 0.0179 | |

a Italicized data were published previously (1).

bp values are as shown.

We also measured Ca2+ dissociation rates using stopped-flow kinetics and the fluorescent Ca2+ chelator Quin-2. With Quin-2, fluorescence increases when it binds Ca2+. In the absence of peptide, the rate of increase in Quin-2 fluorescence can be fit with a single exponential because the N-lobe Ca2+ dissociation is too fast to be resolved by Quin-2 (represented as a dotted line in Fig. 5C from data presented in Ref. 1). In the presence of CaV1.2 IQ peptide, however, a double exponential dissociation is detected (represented as dashed line in Fig. 5C as performed in Ref. 1). The kinetic constants are similar to those obtained with F19W and F92W (1). We measured the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from CaM in the presence of the CaV1.1 IQ peptide. As expected from the tryptophan fluorescence studies, Ca2+ dissociates faster from CaM when bound to CaV1.1 IQ than when bound to CaV1.2 IQ (Fig. 5C and Table 5). The Quin-2 data also support the existence of a stable intermediate with partially saturated CaM in complex with CaV1.2.

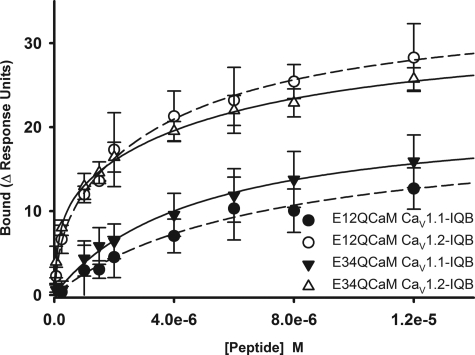

Peptide Binding Affinity of Partially Ca2+-saturated CaM

The lobe-lobe interactions of CaM bound to CaV1.2 raise the issue of Ca2+ binding affinities of CaM lobes. We address this issue by assessing the affinity of the biotinylated wild type IQ peptides for E12QCaM and E34QCaM in saturating Ca2+ concentrations using SPR (Fig. 6). The interactions of E12QCaM and E34QCaM with the CaV1.1 IQB peptide are fit to a one-site saturation model with a KD of 6950 and 4695 nm, respectively, whereas the interactions with CaV1.2 IQB are fit to a two-site saturation model with KD values of 4366 and 197 nm for interaction with E12QCaM and KD values of 5745 and 138 nm for the interaction with the E34QCaM. The drastically reduced affinity of CaV1 peptides for E12QCaM and E34QCaM indicates reduced Ca2+ binding affinity of each lobe of CaM.

FIGURE 6.

Affinity of E12QCaM and E34QCaM for the IQ peptides. Data of E12QCaM binding to CaV1.1 IQB and CaV1.2 IQB and E34QCaM binding to CaV1.1 IQB and CaV1.2 IQB are presented. Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. The lines represent the one and two component fits for the CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ, respectively. The KD values for CaV1.1 IQB-E12QCaM and CaV1.1 IQB-E34QCaM interactions are 6950 ± 1427 and 4694 ± 540 nm, respectively, and for CaV1.2 IQB-E12QCaM are 4366 ± 2283 and 197 ± 157 nm and CaV1.2 IQB-E34QCaM are 5745 ± 1626 and 137 ± 32 nm.

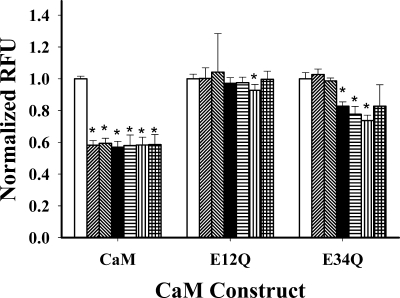

Condensed Versus Extended Conformations of CaM Bound to Peptides

We next used FRET to evaluate proximity of the lobes of CaM to each other when bound to the peptides. We mutated CaM, E12QCaM, and E34QCaM at positions 34 and 110 to place cysteines for labeling with FRET reagents, IAEDNS, and DDPM. DDPM is a nonfluorescent energy-transfer acceptor with IAEDNS as the donor. Residues 34 and 110 of CaM face the solvent in nearly all known structures of CaM and are usually far from the ligand-binding sites. A decrease in the donor fluorescence indicates FRET, as measured relative to CaM labeled with only the donor fluorophore. When fluorescence is decreased in the presence of peptide, the lobes of CaM are closer together. When CaM is labeled with both donor and acceptor (CaMDA), the FRET in the presence of Ca2+ is greater in the presence of the IQ than in its absence (Table 6). The peptides alone increase the fluorescence of CaMD, suggesting that the fluorescence of the donor is somewhat influenced by the peptide under the presented conditions. However, as shown in Table 6, the peptide effects on CaMD fluorescence are not responsible for the FRET with CaMDA and therefore do not affect the ability of the acceptor to quench donor fluorescence. The data summarized in Table 6 indicate that fully Ca2+-bound CaMDA binds to the Cav1.1 IQ and Cav1.2 IQ peptides and assumes a compact conformation with the two lobes in close proximity (Fig. 7 and Table 6). FRET signals were also obtained with both E12QCaM-CaV1.2 IQ and E34QCaM-Cav1.2 IQ (Fig. 7 and Table 6). In contrast, neither the E12QCaM-CaV1.1 IQ nor the E34QCaM-CaV1.2 IQ complex displayed FRET, suggesting that partially saturated CaM does not assume a compact configuration when bound to CaV1.1 IQ. If the Y1675H substitution is made in the CaV1.2 peptide, no FRET was obtained with E34QCaM, indicating that this substitution alters the interaction with the apo-form of the C-lobe. No FRET was detected with E34Q and the CaV1.1 IQ peptide with H1532Y substitution, suggesting this residue alone cannot account for the interaction with the Ca2+-free C-lobe. However, the absence of FRET response could be due to the conformation of the CaV1.1 H1532Y peptide (see supporting information). Conversion of other CaV1.1 amino acids to the corresponding ones in CaV1.2 IQ produced increased FRET values similar to E34Q/CaV1.2 IQ (Fig. 7).

TABLE 6.

Magnitude of fluorescence quenched by peptide relative to CaM molecule labeled with donor and acceptor without peptide

Values in parentheses are (n-numbers).

| CaMDA | CaMD | E12QDA | E12QD | E34QDA | E34QD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No peptide | 1.00 ± 0.02 (8) | 1.00 ± 0.09 (9) | 1.00 ± 0.03 (9) | 1.00 ± 0.07 (9) | 1.00 ± 0.04 (9) | 1.00 ± 0.05 (9) |

| CaV1.1 IQ | 0.58 ± 0.06a (6) | 1.46 ± 0.08a (6) | 1.00 ± 0.07 (7) | 1.12 ± 0.05a (8) | 1.03 ± 0.03 (6) | 1.18 ± 0.06a (6) |

| CaV1.1 IQH1532Y | 0.59 ± 0.03a (6) | 1.53 ± 0.13a (6) | 1.04 ± 0.24 (6) | 1.29 ± 0.16a (6) | 0.99 ± 0.02 (6) | 1.40 ± 0.06a (6) |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K | 0.57 ± 0.04a (6) | 1.46 ± 0.11a (6) | 0.97 ± 0.04 (6) | 1.08 ± 0.08 (6) | 0.83 ± 0.03a (6) | 1.28 ± 0.12a (6) |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/Q1540K) | 0.58 ± 0.04a (3) | 1.50 ± 0.06a (3) | 0.99 ± 0.03 (3) | 1.19 ± 0.08 (3) | 0.78 ± 0.03a (3) | 1.33 ± 0.04a (3) |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/E1542Q | 0.60 ± 0.01a (3) | 1.52 ± 0.08a (3) | 0.92 ± 0.17 (5) | 1.32 ± 0.16a (6) | 0.87 ± 0.04a (3) | 1.29 ± 0.02a (3) |

| CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K | 0.58 ± 0.07a (8) | 1.44 ± 0.10a (8) | 0.98 ± 0.03 (8) | 1.11 ± 0.10 (8) | 0.78 ± 0.05a (8) | 1.23 ± 0.08a (8) |

| CaV1.2 IQ | 0.58 ± 0.05a (6) | 1.45 ± 0.11a (6) | 0.93 ± 0.04a (8) | 1.11 ± 0.07a (9) | 0.74 ± 0.03a (6) | 1.14 ± 0.18 (6) |

| CaV1.2 IQ/Y1675H | 0.59 ± 0.06a (6) | 1.42 ± 0.14a (6) | 1.00 ± 0.06 (6) | 1.09 ± 0.10 (6) | 0.83 ± 0.13 (6) | 1.20 ± 0.13a (6) |

ap value<0.01 by Student's t test compares CaM with peptide to CaM with no peptide.

FIGURE 7.

FRET to compare ability of peptides to bind both lobes of CaM. CaM and peptide concentrations were 200 nm and 2 μm, respectively. Bars represent data from cysteine mutant CaMs labeled with both donor and quenching acceptor. In all CaM groups, empty bars indicate no peptide; forward slanting diagonal lines indicate CaV1.1 IQ peptide; backward slanting diagonal lines indicate CaV1.1 H1532Y peptide; filled bars indicate CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K peptide; horizontal lines indicate CaV1.1/H1532Y/M1537K/Q1540K peptide; vertical lines indicate CaV1.2 IQ peptide; cross-hatched lines indicate CaV1.2 Y1675H. (*, p value <0.005 compared with no peptide.)

DISCUSSION

One mechanism that would allow CaM to regulate the response of different target proteins to different Ca2+ signals is for the binding sites themselves to regulate the Ca2+ affinity of the bound CaM. We provide evidence for this mechanism by demonstrating that subtle differences in CaM-binding sites of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 lead to differences in the Ca2+ binding properties of the lobes of CaM. Assuming these findings accurately reflect Ca2+ sensing by CaM bound to L-type Ca2+ channels, then calmodulin modulation of CaV1.2 channels would be expected to be more sensitive to Ca2+ than that of CaV1.1 channels. In CaV1.2, the tyrosine at residue 1675 has contact with methionines in the C-lobe of CaM and also interacts through a hydrogen bond involving a water molecule and the C-lobe backbone. This difference in conformation compared with CaM in complex with CaV1.1 is likely to contribute to the higher affinity of CaV1.2 IQ for CaM. In CaV1.1 the histidine (His-1532) in place of the tyrosine is likely to increase the flexibility of the 3–4 loop of CaM and Phe-1533 of CaV1.1 IQ, resulting in fewer stabilizing interactions and lower affinity. The amino acid in this position (Tyr-1674 in CaV1.2 and His-1532 in CaV1.1) is obviously important for affinity of CaM for the peptide, but it does not fully account for differences in the Ca2+ affinity of CaM bound to peptides. Our data suggest that the other three amino acids that differ between these two peptides and do not directly contact CaM when CaM is fully Ca2+-saturated participate in the binding of CaM that has one or both lobes Ca2+-free. This argues that different conformations of CaM bind to CaV1.2. Although several studies from other laboratories have shown that the Ca2+ affinity of CaM is influenced by binding to different targets (34, 38–41), we elucidated the contributions of the nonconserved amino acids within the IQ-binding site responsible for this effect on Ca2+ affinity, and we demonstrated that these amino acids play a role in regulating the apparent Ca2+ affinity by modulating the interactions with CaM with at least one lobe Ca2+-free. Additional contributions from channel sequence outside the IQ-binding site studied in this work are likely to contribute to CaM interactions. Recent structural data from CaV1.2 (42) and biochemical studies with longer peptides from both CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 channels (43) suggest that CaM interacts with the “pre-IQ” regions. Thus differences in these regions could play a role in the difference between the CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 channel interactions with CaM.

In the Ca2+-CaM/CaV1.2 structure, Lys-1680 contacts the C-lobe through a water molecule. A question arising from the differences in affinity of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2 for Ca2+-CaM is whether the CaV1.2 IQ lysines electrostatically attract the negatively charged CaM. CaM is an acidic protein with a net negative charge (−16e) and a calculated pI of 4.15 (44). The peptide CaV1.2 IQ has a +3 greater net charge over CaV1.1 IQ, having theoretical pI values of 10.12 and 9.52, respectively. The salinity of the solvent and the positive charges on the peptides may stabilize the compact conformation of the CaM allowing its negatively charged lobes to be close together (45).

Although the parallel arrangement of the N- and C-lobes of CaM bound to CaV1.1 IQ peptide presented here is in agreement with the arrangement seen with the CaV1.2 IQ and other peptides (28, 35, 36), it is opposite to the structure of three CaV2 IQ-Ca2+CaM complexes reported by Kim et al. (46). In these structures CaM is bound in an anti-parallel arrangement, with the N-lobe of CaM binding the carboxyl terminus of the CaV2-IQ peptide and the C-lobe binding the amino terminus of CaV2-IQ.

Our data suggest that CaM has the ability to bind to CaV1.2 IQ, in both a fully and a partially Ca2+-saturated state with higher affinity than to CaV1.1. Recently Saucerman and Bers (47) suggested that the affinity of proteins for CaM determines their response to local Ca2+ signals. In the case of the CaV1 channels discussed here, the different affinities of skeletal and cardiac isoforms for fully or partially Ca2+-saturated CaM could indicate selective modulation and fine-tuning of local Ca2+-dependent pathways or more specifically their CDI and CDF.

In the case of the CaV1.2 channel, it has been suggested that the Ca2+-C-lobe CaM interaction is important for CDI (11), whereas the Ca2+-N-lobe interaction participates in the CDF (35, 36). Given the similarity in the structural arrangement of CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ complexes with CaM, similar responses are expected for CaV1.1. Furthermore, because the nonconserved amino acids between CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ domains are involved in the interactions with CaM C-lobe, both CaV1.1 IQ and CaV1.2 IQ domains are expected to have similar response to CDF, which is modulated by the CaM N-lobe.

The Ca2+ titration of the fluorescence of F92WCaM in complex with CaV1.2 shows evidence of two components (increase followed by a decrease in fluorescence with increasing Ca2+). Substitution of any of the amino acids in CaV1.2 for those in CaV1.1 eliminates the second phase fluorescence quenching, suggesting that all of these amino acids contribute to this second Ca2+-dependent event. The biphasic Ca2+ response of F92WCaM bound to CaV1.2 IQ is best explained by the binding of Ca2+ at the C-lobe at Ca2+ concentrations less than 100 nm followed by a change in the environment of the tryptophan at amino acid 92 (reflected by a quenching of the fluorescence) when Ca2+ binds to the N-lobe. The ability of the Trp-92 to sense Ca2+ binding to both lobes may reflect its location in the linker helix that connects the lobes. The tryptophan at position 19 in the N-lobe is less likely to sense Ca2+ binding at the C-lobe because it is not directly connected to the linker helix. A two-phase Ca2+ equilibrium curve is not apparent when F92W binds to CaV1.1 IQ.

Indirect Ca2+ dissociation data with F92W also reveal a stable Ca2+ intermediate state for CaM binding to CaV1.2 IQ that is not seen with CaV1.1 IQ. During Ca2+ dissociation, the fluorescence of F92W first increases then decreases (1), suggesting that Ca2+ dissociates first from the N-lobe relieving the fluorescence quenching and then dissociates more slowly from the C-lobe. These data again support the existence of a stable intermediate state of CaM with the C-lobe Ca2+-bound and the N-lobe Ca2+-free. This state is likely to exist in a cell when the Ca2+ concentration is declining after a transient. The question becomes what is the functional role of this intermediate state? A Ca2+-binding site mutant that cannot bind Ca2+ at the N-lobe still supports Ca2+-dependent inactivation of this channel, and hence the role of this intermediate form may be to help to close or inactivate the channel. The FRET data suggest that CaM can also interact with CaV1.2 in a compact conformation with the C-lobe Ca2+-free and the N-lobe Ca2+-bound. This would be expected to be the first change in CaM bound to the channel when Ca2+ begins to rise in a cell at the start of the Ca2+ transient. Yue and co-workers (2) suggested that Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe drives Ca2+-dependent facilitation. We conclude that CaM with intermediate saturation states can assume very different conformations depending on whether the N- or C-lobe is Ca2+-bound and in doing so may produce very different functional outcomes.

The IQ motif is likely to be at least part of the binding site for apoCaM (Ca2+-free CaM) (1, 9, 13, 25), but the amino acid residues involved in the binding of apoCaM have not yet been identified. Our data suggest that at least with the partially Ca2+-saturated states the apo-N-lobe and the apo-C-lobe can bind within the IQ sequence of CaV1.2, and the residues at positions Tyr-1675, Lys-1680, Lys-1683, and Gln-1685 contribute to the interaction. A more detailed analysis of CaM interactions with larger regions of the C-tail is needed to determine how CaM can move within its binding pocket upon binding Ca2+. In addition other parts of the channel itself may interact near or with the IQ motif. A recent report by Dick et al. (48) suggests that the N-lobe of a single CaM molecule switches to an amino-terminal site on the CaV1 channels. CaM binding could either promote or inhibit protein-protein interactions.

Our previous studies and those of Van Petegem et al. (36) suggest that CaM is most likely binding with both lobes Ca2+ saturated to determinants within the IQ motif during CDF rather than CDI (28, 36). The data presented here provide the tools needed to test this hypothesis by providing a means to alter the Ca2+ sensitivity of CaM. Our studies also provide details of how the binding site itself regulates the affinity of EF hands of CaM for Ca2+ and identifies new interactions that contribute to CaM binding to the IQ motif.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Henry Bellamy and David Neau for their services at the Center for Advanced Microstructures and Devices Gulf Coast Protein Crystallography Consortium beamline. We also thank Dr. Timothy Palzkill for access to the Biacore3000.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR44864 (to S. L. H.), HL087099 (to S. E. P.), and GM021371 (to F. A. Q.). This work was also supported by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to S. L. H.) and Welch Foundation Grant Q-0581 (to F. A. Q.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains data of CaM affinity for the mutant IQ peptides and the CD spectra of the IQ peptides CaV1.1 IQ, CaV1.2 IQ, CaV1.1 H1532Y, and CaV1.2 Y1675H.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2vay) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- CaM

- calmodulin

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- N-lobe

- amino-terminal domain of calmodulin

- C-lobe

- carboxy-terminal domain of calmodulin

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- apoCaM

- Ca2+-free calmodulin

- Ca2+-CaM

- calmodulin bound to four Ca2+

- CDF

- Ca2+-dependent facilitation

- CDI

- Ca2+-dependent inactivation

- MOPS

- 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- IAEDANS

- 5-((((2-iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino)naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid

- DDPM

- N-(4-dimethylamino-3,5-dinitrophenyl)maleimide

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- CaMDA

- calmodulin labeled with donor and acceptor

- CaMD

- calmodulin labeled with donor only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black D. J., Halling D. B., Mandich D. V., Pedersen S. E., Altschuld R. A., Hamilton S. L. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tadross M. R., Dick I. E., Yue D. T. (2008) Cell 133, 1228–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houdusse A., Gaucher J. F., Krementsova E., Mui S., Trybus K. M., Cohen C. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19326–19331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drum C. L., Yan S. Z., Bard J., Shen Y. Q., Lu D., Soelaiman S., Grabarek Z., Bohm A., Tang W. J. (2002) Nature 415, 396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meador W. E., Means A. R., Quiocho F. A. (1992) Science 257, 1251–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meador W. E., Means A. R., Quiocho F. A. (1993) Science 262, 1718–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumacher M. A., Rivard A. F., Bächinger H. P., Adelman J. P. (2001) Nature 410, 1120–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elshorst B., Hennig M., Försterling H., Diener A., Maurer M., Schulte P., Schwalbe H., Griesinger C., Krebs J., Schmid H., Vorherr T., Carafoli E. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 12320–12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson M. G., Liang H., Mori M. X., Yue D. T. (2003) Neuron 39, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pate P., Mochca-Morales J., Wu Y., Zhang J. Z., Rodney G. G., Serysheva I. I., Williams B. Y., Anderson M. E., Hamilton S. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39786–39792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson B. Z., DeMaria C. D., Adelman J. P., Yue D. T. (1999) Neuron 22, 549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitt G. S., Zühlke R. D., Hudmon A., Schulman H., Reuter H., Tsien R. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30794–30802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W., Halling D. B., Black D. J., Pate P., Zhang J. Z., Pedersen S., Altschuld R. A., Hamilton S. L. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 1538–1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zühlke R. D., Pitt G. S., Deisseroth K., Tsien R. W., Reuter H. (1999) Nature 399, 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroffekova K. (2008) Pfluegers Archiv. 455, 873–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang H., DeMaria C. D., Erickson M. G., Mori M. X., Alseikhan B. A., Yue D. T. (2003) Neuron 39, 951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J., Ghosh S., Nunziato D. A., Pitt G. S. (2004) Neuron 41, 745–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobrinsky E., Schwartz E., Abernethy D. R., Soldatov N. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5021–5028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudmon A., Schulman H., Kim J., Maltez J. M., Tsien R. W., Pitt G. S. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 537–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouton J., Ronjat M., Jona I., Villaz M., Feltz A., Maulet Y. (2001) FEBS Lett. 505, 441–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sencer S., Papineni R. V., Halling D. B., Pate P., Krol J., Zhang J. Z., Hamilton S. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38237–38241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong L., Zhang J. Z., He R., Hamilton S. L. (2006) Biophys. J. 90, 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolmetsch R. E., Pajvani U., Fife K., Spotts J. M., Greenberg M. E. (2001) Science 294, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black D. J., Tikunova S. B., Johnson J. D., Davis J. P. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 13831–13837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiong L., Kleerekoper Q. K., He R., Putkey J. A., Hamilton S. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7070–7079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong L. W., Newman R. A., Rodney G. G., Thomas O., Zhang J. Z., Persechini A., Shea M. A., Hamilton S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40862–40870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodney G. G., Williams B. Y., Strasburg G. M., Beckingham K., Hamilton S. L. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 7807–7812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallon J. L., Halling D. B., Hamilton S. L., Quiocho F. A. (2005) Structure 13, 1881–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossmann M. G. (1972) The Molecular Replacement Method, (Rossman M. G. ed) Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sack J. S., Quiocho F. A. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 277, 158–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rovati G. E., Nicosia S. (1994) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 15, 140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson J. D., Snyder C., Walsh M., Flynn M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mori M. X., Vander Kooi C. W., Leahy D. J., Yue D. T. (2008) Structure 16, 607–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Petegem F., Chatelain F. C., Minor D. L., Jr. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1108–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukherjea P., Maune J. F., Beckingham K. (1996) Protein Sci. 5, 468–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayley P. M., Findlay W. A., Martin S. R. (1996) Protein Sci. 5, 1215–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaertner T. R., Putkey J. A., Waxham M. N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39374–39382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olwin B. B., Storm D. R. (1985) Biochemistry 24, 8081–8086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peersen O. B., Madsen T. S., Falke J. J. (1997) Protein Sci. 6, 794–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fallon J. L., Baker M. R., Xiong L., Loy R. E., Yang G., Dirksen R. T., Hamilton S. L., Quiocho F. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5135–5140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohrtman J., Ritter B., Polster A., Beam K. G., Papadopoulos S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29301–29311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker S. W., Wark J. D., MacNeil S., Mellersh H., Brown B. L., Tomlinson S. (1984) Biochem. J. 217, 827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.André I., Kesvatera T., Jönsson B., Linse S. (2006) Biophys. J. 90, 2903–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim E. Y., Rumpf C. H., Fujiwara Y., Cooley E. S., Van Petegem F., Minor D. L., Jr. (2008) Structure 16, 1455–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saucerman J. J., Bers D. M. (2008) Biophys. J. 95, 4597–4612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dick I. E., Tadross M. R., Liang H., Tay L. H., Yang W., Yue D. T. (2008) Nature 451, 830–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.