Abstract

The Mpz (myelin protein zero) gene codes for the principal component of myelin in the peripheral nervous system, and mutations in this gene cause human peripheral myelinopathies. Expression of the Mpz gene is controlled by two major transactivators that coordinate Schwann cell development: Egr2/Krox20 and Sox10. Our in vivo ChIP-chip analysis in myelinating peripheral nerve identified major sites of Egr2 interaction within the first intron of the Mpz gene and ∼5 kb upstream of the transcription start site. In addition, the sites of Egr2 binding display many of the hallmarks associated with enhancer elements. Interestingly, the upstream Egr2 binding sites lie proximal to the divergently transcribed succinate dehydrogenase C gene, but Sdhc expression was not affected by the massive induction of Mpz mediated by Egr2. Mpz induction was greatly enhanced in the presence of the Egr2 binding sites, and removal of them markedly diminished transgenic expression of a construct derived from the Mpz locus. Sox10 was also found to be associated with the upstream region, and its binding was required for Egr2-mediated activation in this distal regulatory region. Our findings highlight that peripheral nerve-specific expression of Mpz is primarily regulated by both upstream and intron-associated regulatory elements. Overall, these results provide a locus-wide analysis of the role and activity of Egr2 in regulation of the Mpz gene within its native chromosomal context.

The Mpz (myelin protein zero) gene is expressed at basal levels in embryonic Schwann cells as they differentiate from the neural crest and then becomes induced to extremely high levels when axon-dependent signals prompt myelination of peripheral nerves. As such, the product of the Mpz gene constitutes up to 50% of mature myelin protein (1–4). The MPZ gene itself is mutated in a significant proportion of human peripheral neuropathies. In addition, the induced level of Mpz must be strictly controlled, since either haploinsufficiency or mild overexpression of Mpz in mice causes impaired myelin structure (reviewed in Ref. 5).

Previous studies identified two transactivators that convergently regulate the Mpz gene. Sox10 is a Schwann cell specification factor that binds several sites in the Mpz promoter and is required for expression of Mpz at several stages of Schwann cell development (6, 7). However, although the Mpz promoter can drive low expression of transgenic reporters in Schwann cells (8), further analysis indicated that important elements required for consistent, high expression of Mpz lie downstream of the promoter (9). We recently identified a conserved element within the first intron of the Mpz gene, containing binding sites for Sox10 and another transactivator, Egr2/Krox20 (10). This zinc finger protein is induced by axonal signals and is required for initiating and maintaining a high level of Mpz expression in myelinating Schwann cells (11–14). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)2 experiments in myelinating peripheral nerve were consistent with the intron element performing an important role in combinatorial control of Mpz expression (10, 15, 16). Interestingly, Egr2 binding sites have been identified in introns of other myelin genes (15, 17). However, the function of the Mpz intron-associated enhancer in relation to other regulatory elements of the Mpz locus has not been determined.

There are several examples of tissue-specific gene regulation that depends on long range interactions between various regulatory elements, some of which lie within introns or downstream of the gene itself (reviewed in Refs. 18 and 19). Here, we have examined the Mpz locus in its native chromosomal context to elucidate the mechanism by which Egr2 causes focused, tissue-specific regulation of Mpz in myelinating Schwann cells. These studies have unexpectedly revealed a second Mpz regulatory element that lies proximal to the divergently transcribed Sdhc (succinate dehydrogenase subunit C) gene, which is ubiquitously expressed and is not significantly changed in microarray analyses of peripheral nerve myelination (20, 21). Moreover, we have shown that Egr2 binding to both the intron-associated and upstream enhancers is required for high level induction of Mpz expression in transgenic assays. Overall, these data provide a unique mechanism for tissue-specific induction of a vital myelin gene, the expression of which must be tightly controlled for proper myelin formation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

ChIP and ChIP-chip Assays

All antibodies used in this study are listed in the supplemental material. Cell line and in vivo ChIP assays were performed as previously described, and all data are representative of at least two independent experiments (15). Quantitative PCR was performed in duplicate to calculate the percentage recovery of a given segment relative to the total input, using the comparative Ct method (22). As for ChIP-chip assays performed with three independent sample sets, amplicons were generated from ChIP products by either LM-PCR or WGA (23, 24). Labeling of samples with Cy5 (experimental, Egr2) or Cy3 (control, either IgG or total input) and microarray hybridization were performed by Nimblegen, using a custom microarray designed with isothermic probes staggered by 12 bp spanning the entire Mpz locus including up to 20 kb of 5′- and 3′-flanking regions. The enrichment ratio of Cy5 to Cy3 was plotted on a log2 scale and was further processed to display a moving average using a window size of five probes. Island probes that were not neighbored by at least two consecutive 5′- and 3′-flanking probes were delisted. Employing the previously defined method (25), individual peaks were detected in the sequence length of 1556 probes representing the Mpz locus in each array at the stringency of 95th percentile and three-probe width, which corresponds to p < 0.005. Raw data and three-probe moving average data from individual ChIP-chip assays are also included in the supplemental material.

Sequence Analysis

The rVISTA program (26) was applied to recognize putative Egr2 and Sox10 sites, which were subsequently evaluated by comparison with the previously defined consensus Egr2 and Sox10 binding sites (27, 28).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection/Infection Assays

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was supplemented with 5% bovine growth serum for the S16 rat Schwann cell line or with 10% fetal bovine serum for the JTC-19 rat lung fibroblast cell line and B16/F10 mouse melanoma cell line. LT-1 transfection reagent (Mirus) was used to transiently transfect B16/F10 cells for 48 h according to the manufacturer's protocol, and luciferase reporter assays were conducted in duplicate, as previously described (29). For B16/F10 cell infection, the cells were treated in serum-free medium with recombinant adenovirus prepared as described (30) for 24 h and later maintained in growth medium for another 24 h.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR Analysis

RNA was purified using either the TRI Reagent (Ambion) for cell lines or RNeasy Lipid Tissue kit (Qiagen) for tissues including sciatic nerve, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed in duplicate, as described previously (29).

Plasmids

A fragment (−6046 to +2855 relative to the transcription start site) of the mouse Mpz gene was fused into the pGL3 luciferase vector (Promega) with modifications that mutate the start codon in the 1st exon. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to alter Egr2 sites to guanine at positions 2 and 8 of the G-rich strand (27) and Sox10 sites to guanine at positions 4 and 5 on the CA-rich strand (31) to abrogate Egr2 and Sox10 DNA binding in the indicated sites.

Transgenic Mice

All experiments on mice/rats were performed in strict accordance with experimental protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine). All of the transgenes used in this study were linearized by restriction digestion (NotI and SalI) and microinjected into the pronucleus of FVB/N one-cell embryos at the UW Transgenic Animal Facility or University of Wisconsin Waisman Center Rodent Models Core. At postnatal day 10, various tissues, including sciatic nerve, were collected for luciferase expression analysis by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

In Vivo Optical Imaging

A standard optical imaging technique was employed, as described previously (32, 33). A 15 mg/ml stock of d-luciferin (potassium salt; Caliper Life Sciences) was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline and filtered using a 0.22-μm filter before use. Mice 4 weeks old were anesthetized by isoflurane and injected with 200 μl of d-luciferin (150 mg/kg body weight) via tail vein. 20 min later, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and skin was removed. Gray scale body surface images were first taken, and subsequently, bioluminescence images were recorded in a 4-min acquisition time at a field of view of 10, binning of 2 (high resolution), 1 f/stop (lens aperture), using the cooled CCD (charge-coupled device) camera of the in vivo imaging system (IVIS; Xenogen). The gray scale photographic images and bioluminescence images were superimposed using the LivingImage software (Xenogen), and the relative light intensities were displayed in the color range of violet (least intense) to red (most intense). Signal intensities were presented in photons/s/cm2/steradian.

RESULTS

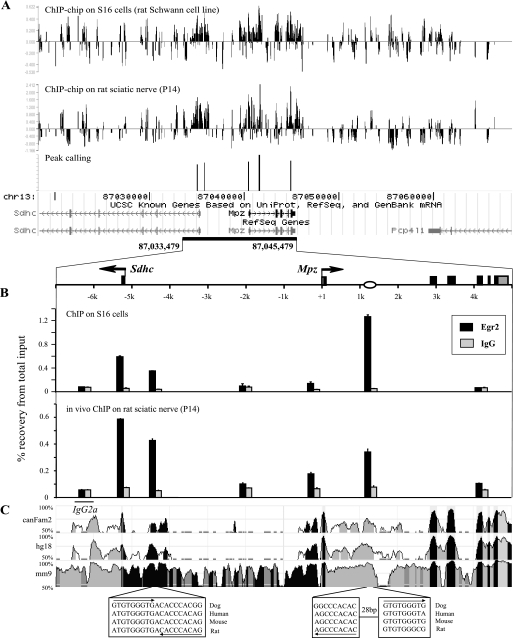

Identification of Novel Egr2 Binding Sites −5 kb Upstream of the Mpz Gene

We have recently reported that Egr2 activates Mpz by associating with the first intron element, located ∼1.3 kb downstream of the transcription start site (10). The unusual binding position in the intragenic region prompted us to investigate the entire Mpz locus in search of additional elements regulated by Egr2. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation in conjunction with DNA microarray analysis (ChIP-chip analysis), we examined 50 kb surrounding the Mpz gene for Egr2 binding sites using the S16 rat Schwann cell line, which exhibits high levels of Mpz expression comparable with those in myelinating Schwann cells (34). As an independent screen for Egr2 binding sites, a similar assay was performed in vivo on rat sciatic nerve, where Egr2 is specifically expressed in myelinating Schwann cells (35, 36).

The resulting analysis identified not only the first intron element described previously but also potential Egr2 binding sites in the promoter region, the fourth exon as well as two sites approximately −5 kb upstream of the Mpz gene (Fig. 1A). To independently test these sites, conventional ChIPs were performed both in S16 cells and in vivo using primer sets targeted to the potential binding sites recognized by the ChIP-chip analysis as well as two negative control sites: one within the locus (−2.1 kb upstream) and the other outside the locus (the promoter of a silent immunoglobulin gene, IgG2a) (Fig. 1B). Despite differences in binding intensity on an individual site basis, the overall patterns of Egr2 enrichment were consistent in S16 cells and in vivo, pointing out three major binding sites, one found in the first intron and two novel sites approximately −5 kb upstream of Mpz, which are located proximal to the divergently transcribed Sdhc gene. Some Egr2 binding was observed in the Mpz promoter region, although this binding appears weaker and less reproducible in standard ChIP assays (data not shown). As shown in the homology plot of the locus, Egr2 was observed to bind to highly conserved regions (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, sequence analysis revealed that one of the two upstream binding sites contains two inverted Egr2 consensus sequences with 100% homology among humans, mice, and rats.

FIGURE 1.

Egr2 is associated with the −5 kb upstream region and first intron element of Mpz. A, ChIP samples were obtained from S16 cells using an antibody to Egr2 or nonspecific IgG as a control and were later labeled with Cy5 (Egr2) or Cy3 (IgG) for hybridization to a tiled oligonucleotide array (top). In vivo ChIP-chip was performed similarly on rat sciatic nerve at postnatal day 14 (P14), a time point of high expression of Mpz (48) using total input DNA as reference (middle). The enrichment ratio of Cy5 to Cy3 was plotted on a log2 scale and further processed to identify common peaks in both S16 cells and sciatic nerve at a height threshold of 95th percentile and a width threshold of three probes in a row (p < 0.005) (bottom). The diagram below depicts the chromosomal region of the Mpz locus represented on the tiled array. These data are representative of three independent experiments. Gaps in the tiling represent repetitive DNA regions for which unique, optimal probes could not be designed. Sdhc, succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit C. Pcp4l1, Purkinje cell protein 4-like 1. B, conventional ChIP assays were performed in S16 cells (top) and in vivo on rat sciatic nerve at P14 (bottom) using an antibody to Egr2 or nonspecific IgG as a control. Enrichment of Egr2 was analyzed by quantitative PCR and shown in the amount of DNA recovered relative to the input DNA. The oval on the locus diagram indicates the previously defined first intron element interacting with Egr2. C, the VISTA plot illustrates homology against rat throughout the Mpz locus in the canine, human, and mouse genomes. Sequences show conservation of Egr2 binding sites.

The Upstream Egr2 Binding Sites Display Hallmarks of Cis-regulatory Elements

Recent genome-wide profiling studies have suggested that the enrichment of the CBP/p300 coactivators is an effective marker for functional regulatory elements of active genes. In addition, enhancer elements are also characterized by nucleosome depletion, typically measured by analysis of histone H3 distribution (37). Therefore, we decided to examine the distribution of CBP/p300 and nucleosome density relative to Egr2 binding sites in the Mpz locus using ChIP assays in S16 cells. In addition to the proximal promoter and 1st intron element of Mpz, CBP/p300 was highly enriched in both of the upstream Egr2 binding sites, and this phenomenon was cell type-specific to S16 cells compared with JTC-19 cells (rat lung fibroblasts), where the Mpz locus is inactive (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). JTC-19 cells exhibited some binding of CBP/p300 in the proximal promoter of Sdhc, which is expressed in the fibroblast cell line. However, distinct enrichment of CBP/p300 was observed particularly at −4.5 kb in S16 cells as opposed to the minimal binding (∼2-fold above background) in JTC-19 cells. Interestingly, the parallel ChIP assays for histone H3 that reflect the distribution of nucleosome density in the Mpz locus exhibited an inverse trend featuring histone H3 eviction in all of the three Egr2 binding sites as well as the active Mpz promoter in S16 cells compared with JTC-19 cells (Fig. 2B). Analysis of the first upstream Egr2 binding site is obscured by the presence of the neighboring Sdhc promoter, which is active in both JTC-19 and S16 cells but not regulated during myelination (Fig. S2) (data not shown). Notwithstanding, Egr2 appears to be specifically associated with sites carrying distinctive signatures of cis-regulatory elements (i.e. high CBP/p300 deposition and low H3 density in a cell type-specific manner).

FIGURE 2.

The upstream Egr2 binding sites possess characteristics of regulatory elements. ChIP assays were performed in the S16 Schwann cell line and the JTC-19 fibroblast cell line using antibodies to CBP/p300 (A) and histone H3 (B). Occupancy of CBP/p300 and H3 was plotted as a percentage relative to the input DNA using quantitative PCR designed for the individual sites marked by bars. In the H3 ChIP assays, 25% recovery lines were drawn to indicate equivalent H3 occupancy at nonspecific sites between the cell lines, and percentage recovery of the control ChIP assays using IgG (not shown) ranged from 0.04 to 0.09%. Egr2 binding sites are represented by the ovals in the diagram of the Mpz locus.

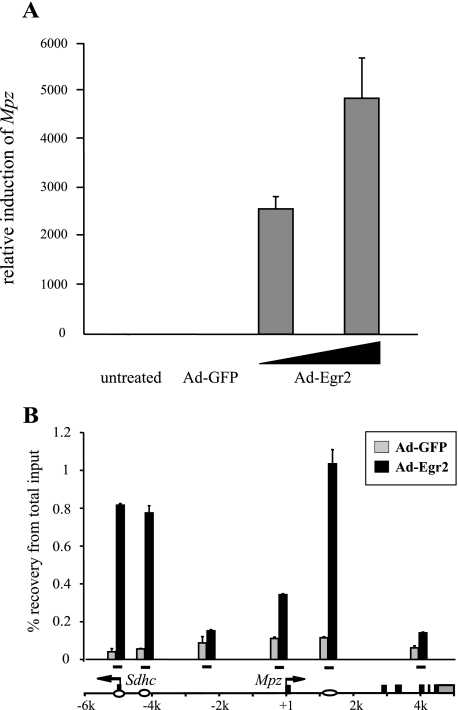

Egr2 Activates Mpz in a Melanocyte Cell Line and Recapitulates a Bimodal Binding Pattern

To examine Egr2-dependent changes in Mpz regulation, we turned to analysis of the B16/F10 melanoma cell line, which has been used previously to study Mpz regulation (38). Melanocytes are neural crest derivatives that also express Sox10 but very low levels of Egr2 and Mpz. First, we tested for the responsiveness of B16/F10 cells to Egr2. Mpz was markedly induced in B16/F10 cells infected with adenovirus expressing Egr2 (Ad-Egr2) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). We also evaluated whether this dramatic induction is directly mediated by Egr2 using ChIP assays in B16/F10 cells infected with either Ad-Egr2 or GFP-expressing adenovirus (Ad-GFP) as a control. Regions of Egr2 enrichment were surveyed by primer sets corresponding to the ones previously used in Egr2-ChIPs in S16 cells and in vivo (Fig. 3B). Clearly, the massive induction of Mpz was correlated with Egr2 binding in the upstream region as well as the first intron element. Since Egr2 displays the similar bimodal binding to the −5 kb upstream and first intron regions in all of the three different Mpz-expressing systems (S16 cells, B16/F10 cells, and myelinating Schwann cells in sciatic nerve), this suggests that Egr2 binding in the upstream region positively regulates the transcriptional activity of Mpz.

FIGURE 3.

Egr2 binding and activation of Mpz in a melanocyte cell line. A, B16/F10 cells were either untreated or infected with Ad-GFP (3.75 × 1010 plaque-forming units) as an infection control or Egr2 (Ad-Egr2; 2.5 × 1010, 3.75 × 1010 plaque-forming units) in 6-well plates and harvested 48 h postinfection. Levels of Mpz expression were measured by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR and normalized to the level of 18 S rRNA. Levels of Mpz induction are plotted relative to that in the untreated sample set as 1. B, using an antibody to Egr2, ChIP assays were performed in the B16/F10 melanocyte cell line 48 h after the infection with adenovirus expressing either Egr2 (Ad-Egr2) or GFP (Ad-GFP) as an infection control. Distribution of Egr2 was determined relative to the input DNA by quantitative PCR targeting the positions marked by the bars in the diagram of the Mpz locus. The ovals indicate Egr2 binding sites identified in S16 cells and sciatic nerve.

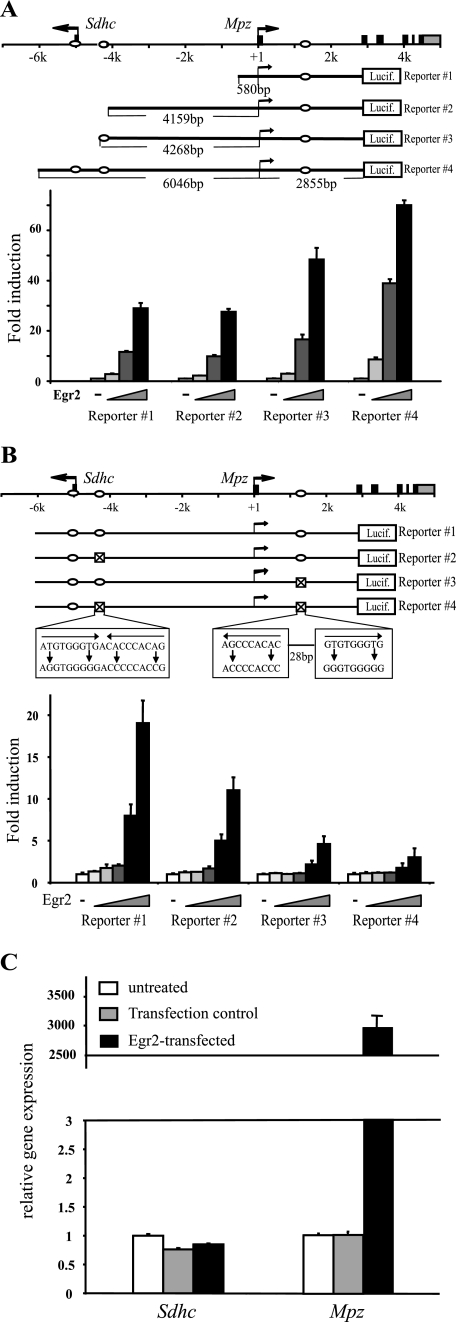

The −5 kb Upstream Region Contributes Unidirectionally to Mpz Induction

To test the significance of the upstream Egr2 binding sites in the induction of Mpz, B16/F10 cells were cotransfected with Egr2 and a series of reporter constructs where the luciferase genes were fused to the second exon of the Mpz locus, retaining the native position of the first intron element (Fig. 4A). First, no further activation was observed in reporter 2 compared with reporter 1, indicating that Egr2-dependent activation is mainly mediated via the first intron element in combination with the proximal promoter. Interestingly, responsiveness to Egr2 was notably enhanced by the sequential addition of the upstream Egr2 binding sites (reporters 3 and 4). A second set of reporter assays with serial mutations that abrogate Egr2 binding in the indicated sites also confirmed that the upstream and first intron regions positively affect Egr2-mediated activation (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the optimal induction of Mpz requires Egr2 binding sites in both the upstream and first intron regions. However, the intriguing location of upstream Egr2 binding in close vicinity of another gene, Sdhc, poses a question of whether Egr2 is also involved in the regulation of Sdhc as well as Mpz. When transfected with Egr2, B16/F10 cells exhibited minimal changes in endogenous Sdhc levels, whereas Mpz was induced >2500-fold, indicating that Egr2 contributes minimally to Sdhc expression (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Egr2-mediated Mpz induction is enhanced by the −5 kb upstream region. A, the indicated reporter constructs were transfected into B16/F10 cells along with increasing amounts (2, 5, or 10 ng) of Egr2, and luciferase assays were performed 48 h posttransfection. -Fold induction was calculated relative to the reporter activity in the absence of Egr2 for each construct. The ovals in the diagram correspond to Egr2 binding sites. B, B16/F10 cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts (0.5, 1, 2, 5, or 10 ng) of Egr2 and each reporter construct indicated and were harvested 48 h posttransfection. Point mutations were introduced to Egr2 consensus binding sequences marked by ⊠ in each construct. -Fold induction is calculated relative to the reporter activity in the absence of Egr2 for each construct. The ovals in the diagram correspond to Egr2 binding sites. C, B16/F10 cells were either untreated or transiently transfected with Egr2 or pBluescript as a transfection control and harvested 48 h posttransfection. Levels of gene expression were measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR and normalized to the level of 18 S rRNA. Expression levels of Sdhc and Mpz are plotted relative to those in the untreated sample set as 1.

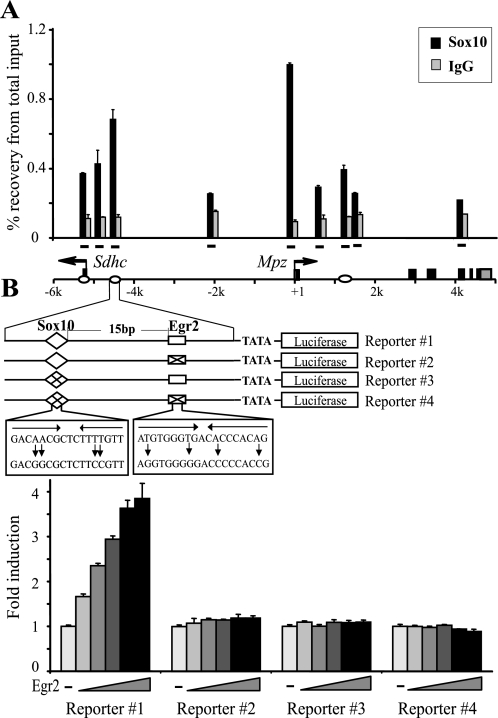

Sox10 Binding Is Required for Egr2-mediated Activation in the Upstream Region

Sox10 has been shown to bind both the promoter and the 1st intron element of Mpz in myelinating sciatic nerve (6, 16), consistent with a critical role of Sox10 in Mpz regulation during myelination. Accordingly, Mpz was down-regulated in S16 cells transfected with Sox10-siRNA (Fig. S3). Interestingly, sequence analysis revealed a conserved pair of Sox10 binding sequences in close proximity of the second upstream Egr2 binding site. Moreover, the inverted orientation and spacing of these sequences bear a striking resemblance to those observed in the first intron element and in other myelin genes (17). ChIP assays demonstrated that Sox10 is physically associated with the upstream region as well as the first intron element and the proximal promoter of Mpz in vivo (Fig. 5A) and in S16 cells (Fig. S4). To further evaluate the role of the upstream Sox10 binding, we conducted reporter assays in B16/F10 cells with constructs containing the second upstream Egr2 binding site and its neighboring Sox10 binding site fused to a minimal promoter (Fig. 5B). As expected, the wild type construct was activated by increasing amounts of Egr2 in a dose-dependent manner (reporter 1). Mutations in the Egr2 binding site completely abolished the responsiveness to Egr2 (reporter 2). Interestingly, mutations in the Sox10 binding site also nullified Egr2-mediated activation (reporter 3). A similar impairment of Egr2 activation of the Mpz intron element was observed when its Sox10 binding sites were mutated (16, 17). Taken together, it appears that Egr2 activation is dependent on adjacent Sox10 binding in the distal regulatory region of Mpz.

FIGURE 5.

Egr2-mediated activation depends on neighboring Sox10 binding in the upstream region. A, in vivo ChIP was performed on rat sciatic nerve at P14 using an antibody to Sox10 or nonspecific IgG as a control. ChIP products were analyzed by quantitative PCR targeting the sites denoted by bars over the Mpz locus. Enrichment of Sox10 is described as percentage of recovery relative to input DNA. Egr2 binding sites are indicated by ovals. B, B16/F10 cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts (5, 10, 20, 40, or 80 ng) of Egr2 and the luciferase reporter constructs indicated and harvested 48 h posttransfection. Point mutations were introduced to prevent Sox10 and/or Egr2 binding, indicated by a diamond containing a cross for Sox10 and ⊠ for Egr2. Data are shown as -fold induction relative to the reporter activity in the absence of Egr2 for each construct.

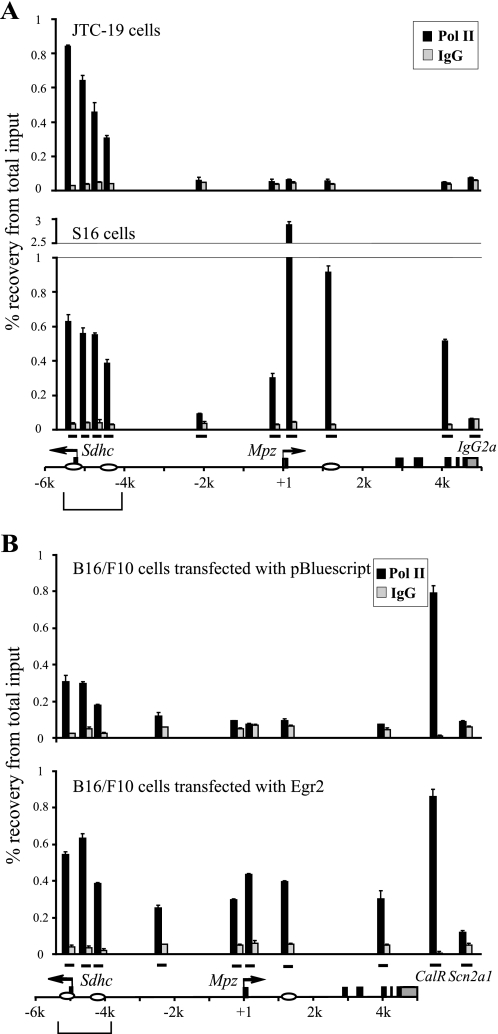

Regulation of Pol II Recruitment to the Mpz Locus

Recent studies have demonstrated recruitment of Pol II (RNA polymerase II) to distal regulatory elements, which is positively correlated with activation of their cognate target genes (39, 40). Using ChIP assays, Pol II occupancy was analyzed in S16 cells, revealing even distribution of Pol II binding over the upstream Egr2 binding sites (Fig. 6A). This is particularly interesting, since previous high resolution mapping studies have indicated a steep loss of Pol II in 5′-flanking regions of active transcription start sites (41), and such a pattern was observed in the corresponding upstream region in JTC-19 cells and Mpz promoter in S16 cells. Parallel analysis for Pol II enrichment was performed in B16/F10 cells transfected with either Egr2 or an empty vector (pBluescript) as a control. As shown in Fig. 6B, significant recruitment of Pol II was observed in the Mpz gene transactivated by Egr2. In addition, Pol II is localized to the promoter region of Sdhc in control cells, but Egr2 expression further enhances the recruitment of Pol II to the −5 kb upstream region compared with the transfection control. This effect is specific to the Mpz locus, as verified by unaffected Pol II binding in control sites: promoters of an active CalR (calreticulin) gene and a silent Scn2a1 (sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, α1) gene.

FIGURE 6.

Egr2 stimulates binding of Pol II to Mpz regulatory elements. ChIP assays were performed with an antibody to Pol II or nonspecific IgG in S16 cells and JTC-19 cells (A) and B16/F10 cells transfected with either Egr2 or pBluescript as a control (B). ChIP products were analyzed by quantitative PCR targeting the sites denoted by bars over the Mpz locus. Enrichment of Pol II is described as a percentage of the input DNA. The −5 kb upstream region is marked by brackets, and Egr2 binding sites are indicated by ovals.

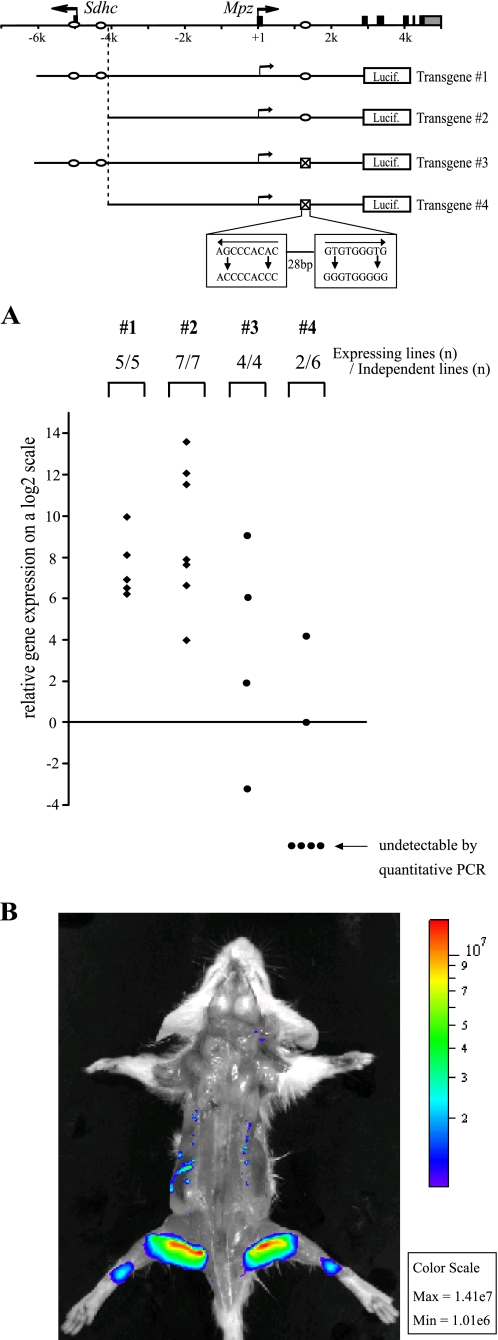

The −5 kb Upstream Region Together with the First Intron Element Is Essential for Mpz Expression in Vivo

Historically, transgenic studies focusing on upstream regions of Mpz have yielded inconsistent expression with the proximal promoter (1.1 kb) and little improvement even with the addition of 9 kb of 5′-flanking sequence (8, 9). Subsequent analysis of transgenes containing the complete Mpz gene, including 6 kb of 5′-flanking region, successfully recapitulated not only the tissue-specific but also the remarkably high levels of expression of endogenous Mpz, shedding a light on the presence of intragenic regulatory elements and their possible cooperation with upstream elements for Mpz regulation (9, 42, 43). Given that Egr2 is a potent regulator of Mpz with major binding sites in the upstream and intragenic regions of the locus, we decided to determine if these sites are required for activation of transgenic constructs derived from the Mpz gene. Transgenic mice were generated with a luciferase reporter gene fused to the second exon of an Mpz gene segment encompassing the entire 6-kb 5′-flanking region, the first exon, and the first intron (transgene 1 in Fig. 7). After microinjection of the transgenic construct, expression levels of the luciferase reporter were determined in peripheral nerve of transgene-positive mouse pups at postnatal day 10. The wild type transgene (transgene 1) was consistently expressed in sciatic nerve (Fig. 7A) but not in other tissues (liver, heart, spleen, and lung; data not shown). Tissue-specific expression of the wild type transgene was also independently evaluated by optical imaging, where bioluminescence of the luciferase reaction was captured by a cooled CCD camera in vivo. After intravenous injection of the luciferin substrate, mice were positioned to optimally image the large sciatic nerve, which lies just beneath the skin of the hind limbs. At the same threshold that eliminated random signals in a non-transgenic littermate (Fig. S5), the transgene directed predominant localization of luminescence in rear legs, indicating its tissue-specific expression in the large sciatic nerve (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Tissue-specific expression of Mpz is governed by the regulatory elements associated with Egr2 in vivo. A, transgenic mice were generated with Mpz-luciferase transgenes illustrated in the diagram and sacrificed at postnatal day 10 for analysis of luciferase expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Each dot represents individual transgenic mice whose transgene expression in sciatic nerve was shown relative to that of one of the transgene 4 mice, which is set to 0 on a log2 scale. Each of the groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test, which indicated that the distribution of transgene 4 differed significantly from transgene 3 (Mann-Whitney U = 21, p = 0.03, one-tailed), and transgene 4 was also significantly different from transgene 1 (U = 30, p = 0.002, one-tailed). In contrast, the same statistical test showed no significant difference between transgene 1 and either transgene 2 or transgene 3. B, a wild type transgenic (transgene 1) mouse at postnatal day 28 was evenly whole skinned and imaged 20 min after the luciferin injection in order to enhance the overall sensitivity of entire body imaging. Signal intensities are presented in photons/s/cm2/steradian, and the relative light intensities are displayed in the color range of violet (least intense) to red (most intense) at the threshold of 1.01 × 106 photons/s/cm2/steradian.

To further evaluate individual contributions of Egr2 binding regions to Mpz expression, the transgene was modified with the deletion of the −5 kb upstream Egr2 binding sites and the mutation of the first intron Egr2 binding sites (transgenes 2, 3, and 4 in Fig. 7). The deletion of the upstream region did not significantly reduce robust expression of the transgene (transgene 2), although there was an apparent increased variability in expression level among all of the seven transgenics. The transgene (transgene 3) with mutations in the intron site only exhibited a reduction in expression levels but still had detectable levels in all four transgenic mice. However, the construct (transgene 4) with impairment in both upstream and intronic Egr2 sites was markedly affected, as indicated in the transgenic founders exhibiting either undetectable (four of six) or considerably lower expression (two of six) compared with the wild type transgene. Overall, these results suggest that the intronic and upstream Egr2 binding sites both play a critical role in Mpz regulation in a partially redundant manner to sustain the optimal levels of stable Mpz expression in peripheral nerve.

DISCUSSION

Proper control of myelination depends on a dramatic induction of the Mpz gene in myelinating Schwann cells. This exquisite, tissue-specific regulation occurs within a chromosomal context in which the ubiquitously expressed Sdhc gene is located only 5 kb upstream of the Mpz promoter. Initial study of Mpz regulation focused on the proximal promoter of Mpz, which interacts with a variety of transcription factors, such as Sox10, Pax3, ZBP99, Sp1, and NF-Y (6, 12, 38, 44). More recently, examination of the intron-associated element has suggested that it plays a central role in Mpz regulation (10). However, application of chromatin immunoprecipitation techniques to myelinating peripheral nerve in vivo has now allowed us to develop a locus-wide view of how Mpz is regulated during myelination. The ChIP-chip analysis identified novel sites of Egr2 binding that lie proximal to the divergently transcribed Sdhc gene. Importantly, the upstream enhancer together with multiple Sox10 binding sites in the promoter region, using up to 9 kb of upstream Mpz sequence, is not sufficient to drive consistent expression in transgenic reporter assays (8, 9). However, the upstream region bears many of the hallmarks of active enhancers, including enrichment of CBP/p300 and lower density of histone H3, as shown in comparison with a fibroblast cell line that does not express Mpz. In addition, the upstream element is required for optimal induction of Mpz in transient transfection assays. Therefore, our data indicate that the upstream sites depend upon interaction with the intron-associated element in order to drive strong expression from the Mpz locus.

Recent genome-wide analyses have revealed a surprising number of DNase-hypersensitive sites within the first introns of many genes (45, 46), and we have also identified Egr2 binding sites within introns of other myelin genes, such as myelin-associated glycoprotein and periaxin (15, 17). However, the mechanistic significance of intragenic enhancers has not yet been fully elucidated. Our data suggest that Egr2 binding at the −5 kb and first intron elements may facilitate loading of RNA polymerase at the Mpz promoter. In this regard, binding of RNA polymerase to both the promoter and the upstream and intron-associated elements is stimulated by expression of Egr2, although the molecular interactions involved in recruitment of RNA polymerase have yet to be elucidated. Given the prevalence of intron-associated regulatory elements, our findings may be generally applicable to other loci with intronic enhancers.

The Mpz gene is a point of convergence between the Sox10 specification factor and the Egr2 regulator that is required for myelination by Schwann cells. Moreover, Mpz expression is very sensitive to expression of a dominant EGR2 (early growth response 2) mutant associated with a severe peripheral myelinopathy (30, 47), and we have recently shown that dominant mutants of Egr2 disrupt cooperative interactions of Egr2 and Sox10 in the intron element (16). The configuration of Egr2 and Sox10 binding sites in the intron-associated enhancer of the Mpz gene is similar to the arrangement of Egr2 and Sox10 binding sites within the upstream enhancer at −5 kb. One of the interesting aspects of both upstream and intron-associated enhancers (16, 17) is that activation by Egr2 is strictly dependent on Sox10 association nearby, indicating mutually dependent activation of these enhancers by Egr2 and Sox10. Our results further indicate that both Egr2 and Sox10 are required for Mpz expression, since our transgenic assays indicate that Sox10 binding sites in the promoter and first intron are not sufficient to drive consistent expression in myelinating peripheral nerve.

The transgenic analysis suggests that the upstream and intron-associated Egr2 binding sites play partially redundant roles in Mpz activation, since destruction of either one alone does not drastically reduce transgenic expression. However, an important caveat to this interpretation is that transgenic insertion generally creates tandemly duplicated copies of the transgene. Therefore, loss of a single enhancer in one transgenic unit could be compensated for to some extent by the presence of enhancers in adjacent copies of the transgenic array. Nonetheless, deletion of both Egr2 binding regions dramatically reduces transgenic expression, indicating that these two sites are major sites of Egr2 activation. The residual activation of the double mutant construct in two of six founders may be due to the retention of Sox10 binding sites in the promoter. Indeed, the proximal promoter can respond weakly to Egr2 in transfection assays (12, 30, 38), and 1.1 kb of the Mpz promoter is also able to drive transgenic expression in Schwann cells, albeit inconsistently (8). Therefore, it is likely that the upstream and intron-associated regions interact with factors such as Sox10 at the promoter region to create the extremely high level of Mpz expression in myelinating Schwann cells.

Overall, our findings indicate that extension of ChIP-chip technology to in vivo situations is useful for analyzing gene regulation within the native physiological context. In addition, such approaches may complement traditional transgenic approaches to analyzing mechanisms of tissue-specific expression by helping to identify elements that may not be sufficient to drive expression in transgenic assays but nonetheless contribute to gene regulation in the native chromatin environment. Given that the majority of human peripheral myelinopathies are caused by relatively subtle changes in expression of myelin genes as a result of altered gene dosage (reviewed in Ref. 5), it will be important to employ such approaches to analyze the interactions of multiple regulatory elements that control myelin gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Ward, Scott LeBlanc, and Stephen Johnson for assistance with cloning, adenovirus preparation, and ChIP analysis. We also thank Joe Oravetz and the University of Wisconsin Transgenic Animal Facility and Albee Messing and Denice Springman in the Waisman Center Rodent Models Core for providing transgenic mice; Richard Quarles for providing the S16 cell line; and Erik Petersen for help with optical imaging. Finally, we are indebted to Aseem Ansari, Joshua Tietjen, and Nolan Gokey for assistance with ChIP-chip data analysis and to Lawrence Wrabetz, Elaine Alarid, and Avtar Roopra for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NICHD, Grant HD41590 (to J. S.) and Core Grant P30 HD03352 (to the Waisman Center).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CBP

- cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein

- Ad

- adenovirus

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- Pol II

- polymerase II.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenfield S., Brostoff S., Eylar E. H., Morell P. (1973) J. Neurochem. 20, 1207–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemke G., Chao M. (1988) Development 102, 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya A., Frank E., Ratner N., Brackenbury R. (1991) Neuron 7, 831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M., Brennan A., Blanchard A., Zoidl G., Dong Z., Tabernero A., Zoidl C., Dent M. A., Jessen K. R., Mirsky R. (1997) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 8, 336–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrabetz L., Feltri M. L., Kleopa K. A., Scherer S. S. (2004) in Myelin Biology and Disorders (Lazzarini R. A. ed) pp. 905–951, Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peirano R. I., Goerich D. E., Riethmacher D., Wegner M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 3198–3209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiner S., Cossais F., Fischer K., Scholz S., Bösl M. R., Holtmann B., Sendtner M., Wegner M. (2007) Development 134, 3271–3281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messing A., Behringer R. R., Hammang J. P., Palmiter R. D., Brinster R. L., Lemke G. (1992) Neuron 8, 507–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feltri M. L., D'antonio M., Quattrini A., Numerato R., Arona M., Previtali S., Chiu S. Y., Messing A., Wrabetz L. (1999) Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 1577–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeBlanc S. E., Jang S. W., Ward R. M., Wrabetz L., Svaren J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5453–5460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topilko P., Schneider-Maunoury S., Levi G., Baron-Van Evercooren A., Chennoufi A. B., Seitanidou T., Babinet C., Charnay P. (1994) Nature 371, 796–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zorick T. S., Syroid D. E., Brown A., Gridley T., Lemke G. (1999) Development 126, 1397–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le N., Nagarajan R., Wang J. Y., Araki T., Schmidt R. E., Milbrandt J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2596–2601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decker L., Desmarquet-Trin-Dinh C., Taillebourg E., Ghislain J., Vallat J. M., Charnay P. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 9771–9779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang S. W., LeBlanc S. E., Roopra A., Wrabetz L., Svaren J. (2006) J. Neurochem. 98, 1678–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBlanc S. E., Ward R. M., Svaren J. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3521–3529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones E. A., Jang S. W., Mager G. M., Chang L. W., Srinivasan R., Gokey N. G., Ward R. M., Nagarajan R., Svaren J. (2007) Neuron Glia Biol. 3, 377–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser P. (2006) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16, 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinjan D. A., van Heyningen V. (2005) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 8–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagarajan R., Le N., Mahoney H., Araki T., Milbrandt J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8998–9003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verheijen M. H., Chrast R., Burrola P., Lemke G. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 2450–2464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberley M. J., Tsao J., Yau P., Farnham P. J. (2004) Methods Enzymol. 376, 315–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Geen H., Nicolet C. M., Blahnik K., Green R., Farnham P. J. (2006) BioTechniques 41, 577–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bieda M., Xu X., Singer M. A., Green R., Farnham P. J. (2006) Genome Res. 16, 595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loots G. G., Ovcharenko I., Pachter L., Dubchak I., Rubin E. M. (2002) Genome. Res. 12, 832–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swirnoff A. H., Milbrandt J. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2275–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harley V. R., Lovell-Badge R., Goodfellow P. N. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1500–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leblanc S. E., Srinivasan R., Ferri C., Mager G. M., Gillian-Daniel A. L., Wrabetz L., Svaren J. (2005) J. Neurochem. 93, 737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagarajan R., Svaren J., Le N., Araki T., Watson M., Milbrandt J. (2001) Neuron 30, 355–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bondurand N., Girard M., Pingault V., Lemort N., Dubourg O., Goossens M. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2783–2795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhaumik S., Gambhir S. S. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 377–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J. C., Sundaresan G., Iyer M., Gambhir S. S. (2001) Mol. Ther. 4, 297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hai M., Muja N., DeVries G. H., Quarles R. H., Patel P. I. (2002) J. Neurosci. Res. 69, 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zorick T. S., Syroid D. E., Arroyo E., Scherer S. S., Lemke G. (1996) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 8, 129–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Topilko P., Levi G., Merlo G., Mantero S., Desmarquet C., Mancardi G., Charnay P. (1997) J. Neurosci. Res. 50, 702–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heintzman N. D., Stuart R. K., Hon G., Fu Y., Ching C. W., Hawkins R. D., Barrera L. O., Van Calcar S., Qu C., Ching K. A., Wang W., Weng Z., Green R. D., Crawford G. E., Ren B. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slutsky S. G., Kamaraju A. K., Levy A. M., Chebath J., Revel M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8960–8968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vernimmen D., De Gobbi M., Sloane-Stanley J. A., Wood W. G., Higgs D. R. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 2041–2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson K. D., Christensen H. M., Zhao B., Bresnick E. H. (2001) Mol. Cell. 8, 465–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T. Y., Schones D. E., Wang Z., Wei G., Chepelev I., Zhao K. (2007) Cell 129, 823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Previtali S. C., Quattrini A., Fasolini M., Panzeri M. C., Villa A., Filbin M. T., Li W., Chiu S. Y., Messing A., Wrabetz L., Feltri M. L. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151, 1035–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wrabetz L., Feltri M. L., Quattrini A., Imperiale D., Previtali S., D'Antonio M., Martini R., Yin X., Trapp B. D., Zhou L., Chiu S. Y., Messing A. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 1021–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown A. M., Lemke G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28939–28947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawford G. E., Holt I. E., Whittle J., Webb B. D., Tai D., Davis S., Margulies E. H., Chen Y., Bernat J. A., Ginsburg D., Zhou D., Luo S., Vasicek T. J., Daly M. J., Wolfsberg T. G., Collins F. S. (2006) Genome Res. 16, 123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabo P. J., Kuehn M. S., Thurman R., Johnson B. E., Johnson E. M., Cao H., Yu M., Rosenzweig E., Goldy J., Haydock A., Weaver M., Shafer A., Lee K., Neri F., Humbert R., Singer M. A., Richmond T. A., Dorschner M. O., McArthur M., Hawrylycz M., Green R. D., Navas P. A., Noble W. S., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A. (2006) Nat. Methods 3, 511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arthur-Farraj P., Mirsky R., Parkinson D. B., Jessen K. R. (2006) Neurobiol. Dis. 24, 159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stahl N., Harry J., Popko B. (1990) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 8, 209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.