Abstract

Fertilization induces a species-specific Ca2+ transient with specialized spatial and temporal dynamics, which are essential to temporally encode egg activation events such as the block to polyspermy and resumption of meiosis. Eggs acquire the competence to produce the fertilization-specific Ca2+ transient during oocyte maturation, which encompasses dramatic potentiation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent Ca2+ release. Here we show that increased IP3 receptor (IP3R) sensitivity is initiated at the germinal vesicle breakdown stage of maturation, which correlates with maturation promoting factor (MPF) activation. Extensive phosphopeptide mapping of the IP3R resulted in ∼70% coverage and identified three residues, Thr-931, Thr-1136, and Ser-114, which are specifically phos pho ryl a ted during maturation. Phospho-specific antibody analyses show that Thr-1136 phos pho ryl a tion requires MPF activation. Activation of either MPF or the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade independently, functionally sensitizes IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. Collectively, these data argue that the kinase cascades driving meiotic maturation potentiates IP3-dependent Ca2+ release, possibly trough direct phos pho ryl a tion of the IP3R.

Egg activation refers to the cellular and molecular events that take place immediately following fertilization, transitioning the zygote into embryogenesis. In vertebrates, egg activation encompasses the block to polyspermy and the completion of oocyte meiosis, which is coupled to the extrusion of the second polar body. Interestingly, in all sexually reproducing organisms tested to date the cellular events associated with egg activation are Ca2+-dependent (1). Importantly the Ca2+ signal at fertilization encodes the progression of these cellular events in a defined temporal sequence that ensures a functional egg-to-embryo transition (2, 3). The first order of business for the fertilized egg is to block polyspermy, which could be lethal to the embryo. This presents a particularly difficult problem for the large Xenopus oocyte. Therefore, this species employs a fast and slow blocks to polyspermy, both of which are Ca2+-dependent (4). In addition, the Ca2+ release wave at fertilization releases the metaphase II cytostatic factor-dependent arrest in Xenopus oocytes. As is the case in other vertebrates, Xenopus eggs arrest at metaphase of meiosis II, an event that marks the completion of maturation.

Therefore, Ca2+ dynamics at fertilization initiate and temporally encode critical cellular events for the egg-to-embryo transition. Specificity in Ca2+ signaling is encoded to a large extent in the spatial, temporal, and amplitude features of the Ca2+ signal. This endows Ca2+ signaling with its versatility and specificity, where in the same cell Ca2+ signals can mediate distinct cellular responses (5, 6).

Ca2+ signaling pathways and intracellular organelles remodel during oocyte maturation, a complex cellular differentiation that prepares the egg for fertilization and egg activation (7, 8). In Xenopus the activity and distribution of multiple essential Ca2+-transporting proteins is modulated dramatically during oocyte maturation (8). Functional studies and mathematical modeling support the conclusion that the two critical determinants of Ca2+ signaling remodeling during Xenopus oocyte maturation are the internalization of the plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPase, and the sensitization of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)2-dependent Ca2+ release (9–11). Indeed Ca2+ release from intracellular stores through the IP3 receptor (IP3R) represents the primary source for the initial Ca2+ rise at fertilization in vertebrates (12–14). The sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release is enhanced during maturation (10, 15). The IP3R physically clusters during maturation (9, 16), and this is associated with functional clustering of elementary Ca2+ release events (10). IP3R clustering is important for the slow and continuous nature of Ca2+ wave propagation in Xenopus eggs (10). In fact the potentiation of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release is a hallmark of Ca2+ signaling differentiation during oocyte maturation in several vertebrate and invertebrate species (17–19). However, the mechanisms underlying enhanced IP3-dependent Ca2+ release are not well understood.

An attractive mechanism to explain increased IP3R sensitivity during oocyte maturation is phosphorylation, given the critical role kinase cascades play in the initiation and progression of the meiotic cell cycle. Furthermore, the affinity of the IP3R increases during mitosis apparently due to direct phosphorylation by maturation-promoting factor (MPF) (20, 21). In contrast, in starfish eggs, although the increase in Ca2+ release was dependent on MPF activation, MPF does not directly phosphorylate the IP3R, but rather it appears to mediate its effect through the actin cytoskeleton (22, 23). More recently, the MAPK cascade has been shown to be important for shaping Ca2+ dynamics in mouse eggs (24). Together, these results argue that phosphorylation plays an important role in the sensitization of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release during M-phase.

Xenopus oocyte maturation is initiated by steroids that appear to act on a cell surface receptor (25). An important kinase cascade activated during maturation is the MAPK cascade that is initiated through the accumulation of Mos (Fig. 1A). This cascade culminates in the inhibition of Myt1, which phosphorylates and inhibits MPF. MPF is the key regulator of entry into M-phase and is composed of a Ser/Thr kinase subunit (cdk1) and cyclin B as a regulatory subunit. In addition, activation of Cdc25C is essential for oocyte maturation, because it represents the rate-limiting step in MPF activation (26). Cdc25C is phosphorylated by polo-like kinase through unknown upstream steps. In this work we analyze the functional regulation and phosphorylation pattern of the IP3R during oocyte maturation to better understand the role of cell cycle kinases in modulating IP3-dependent Ca2+ release.

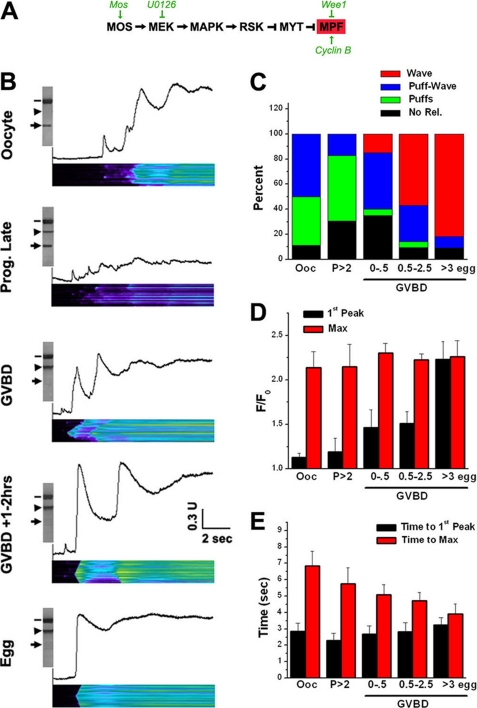

FIGURE 1.

IP3-dependent Ca2+ release dynamics during maturation. A, kinase cascades driving Xenopus oocyte maturation. B, oocytes were injected with caged-IP3 and Oregan Green 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis 1 before imaging. Maturation was induced with progesterone, and cells were collected at different time points as indicated. Cells were imaged in line scan mode on a Zeiss LSM510 with the near UV 450 nm laser continuously on, at low intensity to produce a slow gradual IP3 rise. After imaging each cell was lysed and analyzed individually for the activation state of MAPK and MPF. MPF was assayed using an anti-phospho-Tyr-15-cdk1 antibody (arrow). Dephosphorylation is indicative of MPF activation. MAPK activation was detected using a phospho-specific MAPK antibody (arrowhead). Tubulin was the loading control (dash). C, percent of cells at each time point that either exhibit no release for the duration of the line scan (No Rel., black), puffs only (puffs, green), puffs followed by a wave (Puff-Wave, blue), or only a Ca2+ wave (Wave, red). For each time point n = 11–23 cells. D, amplitude of the first peak during the line scan as compared with the maximal Ca2+ signal. Mean ± S.E. (n = 9–18). E, latency until the first Ca2+ signal (Time to first peak) as compared with the time required to reach maximal signal (Time to Max). Mean ± S.E. (n = 9–18). For C–E: oocytes (Ooc); cells treated with progesterone that have not undergone GVBD at 2 or more hours after progesterone (p > 2); cells at GVBD and up to 0.5 h after GVBD (GVBD 0–0.5); cells from 0.5 to 2.5 h after GVBD (GVBD 0.5–2.5); fully mature eggs at 3 or more hours after GVBD (>3 egg).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Reagents

A portion of the Xenopus IP3R coupling domain (residues 565–1895) was amplified from a Xenopus oocyte library (N. Garret, Wellcome Trust) and subcloned into the SacII-ClaI sites of the oocyte expression vector pSGEM (M. Hollmann, Max-Planck) (27). The forward primer inserts a SacII site, an internal ribosomal binding site followed by a start Met and a FLAG tag in-frame upstream of the IP3R coding sequence: TCCCCGCGGGGAACCACCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGACGACAAGGGCTTTATGCAGAAGCAGATTGGTTATGATGTGTTGG. The reverse primer was CCATCGATGGTGCAACAGCCATCACGCCTTCTCC. pSGEM flanks the cDNA with the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions from the Xenopus globin gene, thus stabilizing the resultant mRNA in the oocyte (42). T931A, T1136A, and the double mutant were engineered using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and sequence-verified. Plasmids were linearized with NheI and transcribed with T7 polymerase using the mMessage mMachine transcription kit (Ambion). Cyclin B1, Mos, and Wee1 RNAs were synthesized from a pXen-GST-Mos, pSP64-cyclinB1xen, and pXen-Wee1 plasmids as previously described (28).

MPF Phosphorylation Assay

Oocytes (150 cells) were subject to immunoprecipitation using custom-made preImmune and immune sera as described below. MPF phosphorylation assays were performed using the SignaTech cdc2 Protein Kinase Assay System (Promega, catalog no. V6430) directly on antigen-antibody complex bound to Protein A/G-agarose beads. The MPF assay consisted of 60 oocytes per reaction containing 0.13 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, 50 μm ATP, 10 units of Xenopus MPF (Calbiochem, catalog no. 506120) in MPF buffer. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS loading and boiling. The samples were then separated on polyacrylamide gel, transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and analyzed by autoradiography. Western analysis was also performed on the same set of IP samples (five oocytes or eggs/sample).

Metabolic Labeling and Immunoprecipitation

Two dishes of oocytes (>1,000 cells each) were labeled with [32P]orthophosphoric acid (10 μCi/μl, PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Progesterone was added to one dish to induce maturation. After overnight incubation oocytes and eggs were harvested and lysed in IP Lysis buffer (in mm: 30 Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 NaCl, 2 sodium vanadate, 50 β-glycerol phosphate, 10 sodium pyrophosphate, 5 EDTA, 5 EGTA, 1 dithiothreitol, plus protease inhibitors, Mixture III, EMD Bioscience). The lysates were centrifuge five times at 1,000 × g to remove particulates, and Nonidet P-40 was added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 2.5%. The samples were incubated for 2 h with rotation at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. IPs were performed using custom-made rabbit anti-IP3R antibodies. Protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used to precipitate the antigen-antibody complex. The bound agarose beads were washed four times with lysis buffer containing 2.5% Nonidet P-40. SDS loading buffer were added to the beads, boiled for 5 min, separated on SDS-PAGE gel, and analyzed by autoradiography. FLAG-tagged regulatory region of the IP3R was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody (Stratagene) followed by protein G-agarose beads. Immunoprecipitation of the IP3R was confirmed by Western blotting.

Antibodies and Western Blots

Custom-made antibodies against the Xenopus type 1 IP3R were generated in rabbits against the C-terminal 19 residues. The specificity of the antibody against the target peptide was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In addition the antibody was validated against commercially available anti-IP3R antibodies (CT-1 and T433 (Upstate)), where commercial antibodies detect the IP3R immunoprecipitated using our custom-made antibody. Our rabbit anti-IP3R antibody (ProteinTech) was used at 1:1000 dilution for Western blots. Phospho-specific antibodies for Thr-931 and Thr-1136 were generated against the following phosphorylated peptides, respectively: N′-C-GGGFLPMT(phos)PMAAPEG and N′-C′AGGADKGET(phos)PGKAKK. Antibodies were affinity-purified against the phosphorylated peptide, and the specificity was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay where the antibody detected the phosphorylated but not the native peptide. These phosphospecific antibodies detected immunoprecipitated IP3R in eggs but not oocytes and were used at 1:500 dilution for Western blots. Other commercially purchased antibodies were as follows: Phospho-(Ser/Thr) PKA substrate mAb (Cell Signaling catalog no. 9624), Phospho-(Ser) CDKs substrate Ab (Cell Signaling catalog no. 2324), Phospho-(Thr) MAPK/CDC substrate mAb (Cell Signaling catalog no. 2321), Phospho MAPK mAb (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9106), Phospho Cdc2 Ab (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9111), Anti-FLAG® M2 antibody (Stratagene catalog no. 200472), and monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma catalog no. T9026). For Western blotting lysates or IP samples were separated on 6 or 10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and blotted with the primary antibodies. This was followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson) and detected by using ECL-Plus (Amersham Biosciences). Western blots were visualized using a StormTM system (Amersham Biosciences).

Ca2+ Imaging

Xenopus oocytes were injected with Oregon Green 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis-1 and caged-IP3 (d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, P4(5)-(1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl) ester, tris triethylammonium salt, Molecular Probes). Ca2+ imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM510 or Olympus Fluoview300 confocal microscope. Because sperm targets the egg's animal hemisphere, all experiments were limited to this pole.

MS Analyses

The IP3R was immunoprecipitated, re-suspended in SDS NuPAGE LDS Sample buffer, and resolved on a 4–12% gradient NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen). The gel was stained with Simply BlueTM SafeStain according to the manufacturer's instructions. The IP3R band was excised and robotically (Progest, Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI) digested with trypsin or chymotrypsin using an in-gel digestion protocol using either trypsin or chymotrypsin (29). The resulting peptide pools were separated by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography using a splitless high-performance liquid chromatography system (Nano LC-2D, Eksigent, Dublin, CA). Peptides were loaded onto a 4-mm × 75-μm column packed with C12 resin (Jupiter proteo 4 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and eluted using a gradient elution (gradient conditions were 0.1–30% B in 35 min, 30–50% B in 10 min, 50–80% B in 5 min) flowing at 200 nl/min over the analytical column (15 cm × 75 μm packed with the same resin). The column was interfaced to a 30-μm × 3-cm stainless steel emitter (Proxeon, Odense, Denmark) onto which 1.8 kV was applied. The peptides were analyzed by an ion trap (LCQ Deca XP Plus, Thermo, San Jose, CA) using data-dependent acquisition. Each scan cycle consisted of one parent MS scan, which utilized an m/z range of 400–1600 followed by 4 MS/MS scans of the four most intense ions that had not been previously selected for fragmentation. Normalized collision activation energy was set at 35%, and three microscans were summed following automatic-gain-control implementation, which consisted of 5 × 108 ions for MS and 6 × 107 ions for MS/MS. Dynamic exclusion was set for 30 s, ensuring that peptides were only selected once for fragmentation.

Data Searching

Data from the MS/MS analysis was searched against the non-redundant NCBI data base for Xenopus laevis proteins using Mascot as the search engine. This process was automated by Mascot Daemon. Peptides were searched with a fixed modification of carbamidomethyl (Cys), and variable modifications of oxidation (Met), phosphorylation of serine or threonine, and phosphorylation of tyrosine. Maximum limit for missed cleavages was set at 2, peptide mass tolerance was set at 2.0 Da, and fragment ion tolerance was set at 0.6 Da. The search results were then parsed into Scaffold (Proteome Software, Portland, OR), which verified peptide identification from Mascot and probabilistically validates these peptide identifications using PeptideProphet (30) and derives corresponding protein probabilities using ProteinProphet (31).

Phosphopeptide Identification

Candidate phosphopeptides (peptides identified by Mascot as phosphorylated) were all manually verified and annotated to ensure genuineness. The fragment ion data were vigilantly examined to ensure sufficient spectral data (both intact ion series as well as ion series containing the typically observed neutral loss) existed to confirm the localization of the phosphorylation site on the peptides containing multiple potential sites.

RESULTS

Ca2+ Release Dynamics during Oocyte Maturation

Several kinase cascades are activated during Xenopus oocyte maturation and regulate critical milestones throughout this complex developmental transition (32). Fig. 1A outlines the salient features of the signal transduction cascade driving oocyte maturation as relevant to this work. We employed functional imaging and biochemical approaches to correlate kinase activation along the oocyte maturation cascade with the sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release.

For these experiments oocytes were loaded with the Ca2+ sensor Oregon-Green 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis, to assess changes in Ca2+ levels and caged IP3 to allow quantitative IP3 generation based on the duration of the uncaging pulse as previously described (9, 10). We first assessed the Ca2+ release response to a gradual slow rise in IP3 in a spatially defined location (Fig. 1, B and C). This was accomplished by continuously uncaging IP3 using the near UV 405 nm laser on an LSM510 confocal in line-scan mode (Fig. 1B). In oocytes this protocol produces Ca2+ puffs, which are initial events, followed by Ca2+ oscillations before the Ca2+ signal plateaus (Fig. 1B, Oocyte).

After imaging, each cell was lysed to analyze the activation state of both MAPK and MPF. This allowed direct correlation at the single cell level between Ca2+ dynamics and kinases activation. Phospho-specific antibodies were employed to visualize the phosphorylation, and thus activation state, of MAPK (Fig. 1B, arrowhead) and MPF (Fig. 1B, arrow), whereas tubulin was used as the loading control (Fig. 1B, line). Detection of a phosphorylated MAPK band indicates activation. In contrast, phosphorylation at Tyr-15 of MPF inhibits the kinase, and thus MPF activation is indicated by loss of the reactive band using the anti-phospho-Tyr-15 antibody (Fig. 1B, arrow).

As oocytes progress through maturation, IP3-dependent Ca2+ release dynamics are altered (Fig. 1, B and C). Two or more hours after progesterone addition oocytes exhibit similar Ca2+ dynamics and were thus pooled for analysis (Fig. 1, B–E, p > 2). The sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release is decreased in this population, especially late after progesterone addition (i.e. ≥70% of the cells in the population have undergone germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD)). This is indicated by the dampened release observed in the representative line scan (Fig. 1B, Prog. Late), the increased percent of non-responding cells (Fig. 1C, p > 2), and the higher percentage of cells that produce only Ca2+ puffs (Fig. 1C, p > 2, Puffs). Therefore, Ca2+ mobilization in oocytes that have initiated maturation, but before GVBD, shifted toward a less responsive mode. In a subset of this population, that is in oocytes 1–2 h before GVBD, MAPK was activated at low levels (Fig. 1B, Prog. Late).

At GVBD, when both the MAPK cascade and MPF are activated, typically fewer Ca2+ oscillations were observed (Fig. 1B, GVBD), and a small percentage of cells produced Ca2+ waves without any observable puffs indicating that the sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was enhanced (Fig. 1C). As maturation progressed further, Ca2+ oscillations were gradually inhibited and were absent in fully mature eggs (Fig. 1, B and C).

In this experimental paradigm of gradually increasing IP3 levels, three measures of Ca2+ dynamics reflect sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. The amplitude of the initial Ca2+ response (Fig. 1D, 1st Peak) as compared with the maximum response (Fig. 1D, Max), the latency to the initial Ca2+ response (Fig. 1E, Time to 1st Peak), and the percent of cells that produce Ca2+ waves (Fig. 1C). The differential between the amplitude of the initial and maximal Ca2+ signals was pronounced in oocytes and gradually decreased as cells progressed through maturation (Fig. 1D). Functionally this results in the suppression of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 1B), which is physiologically significant, because a single sweeping Ca2+ wave is important to trigger and maintain the polyspermy block in eggs (4). Surprisingly, however, the latency to the initial response was not statistically different throughout maturation, and even tended to be longer in eggs (Fig. 1E). The reasons for this observation were not clear, but one possibility is that the gradual increase in IP3 levels in eggs resulted in inactivation of the receptor before an observable Ca2+ release was mounted. Mathematical modeling argues that this mechanism explains the shorter puff duration observed in eggs as compared with oocytes (11).

Ca2+ Mobilization Response during Oocyte Maturation

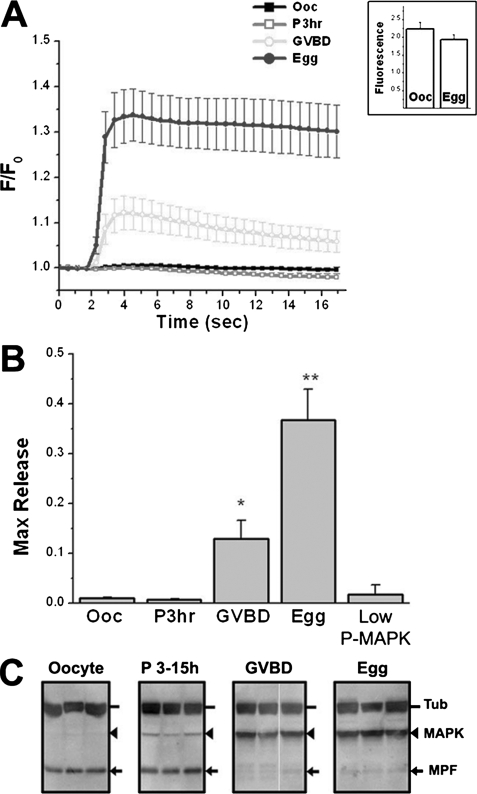

We then tested the Ca2+ mobilization response throughout maturation using a flash uncaging pulse, to determine the instantaneous Ca2+ response following a step rather than gradual IP3 increase (Fig. 2). For each batch of cells the sub-threshold uncaging pulse duration was empirically determined in oocytes and applied to different stages of maturation. Uncaging caged-fluorescein in oocytes and eggs resulted in similar fluorescence signals (Fig. 2A, inset), showing that light penetrance in the two cell types is comparable. We also confirmed the activation states of MAPK and MPF along the maturation pathway (Fig. 2C). As in Fig. 1 cells were lysed individually after imaging, and MAPK and MPF activation was determined (Fig. 2C). Examples from three individual cells are shown (Fig. 2C). The sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release began to increase at the GVBD stage and reached maximal sensitivity in fully mature eggs (Fig. 2, A and B). Similar results were observed in response to a gradual IP3-uncaging protocol in a region of interest (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 2.

Potentiation of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release during oocyte maturation. A, cells were collected and imaged before maturation (Ooc); 3 h after progesterone addition with no GVBD (P3hr); at GVBD (GVBD); and >3 h after GVBD (Egg). IP3 was uncaged using flash photolysis on a Fluoview confocal as previously described (10). A sub-threshold uncaging pulse was empirically determined for each batch of cells in oocytes leading to little or no release and was applied to the other stages of maturation. This uncaging pulse readily induces Ca2+ mobilization in eggs and to a lesser extent in cells at GVBD. The inset shows uncaging levels of caged-fluorescein in oocytes and eggs. B, statistics of maximal Ca2+ release from 19–24 cells in each group (three donor females). The asterisk indicates significantly different data sets (p ≤ 0.0024). The “Low P-MAPK” group refers to cells treated with progesterone before GVBD where low levels of MAPK phosphorylation were detected as shown in the P3–15h panel in Fig. 3C. C, imaged cells were lysed and analyzed individually to test the activation state of MAPK (arrowhead) and MPF (arrow) in the different groups. Tubulin (Tub, dash) was the loading control. Examples of three individual cells are shown for each time point. For the P3–15h group cells with low MAPK activity (1–2 h before GVBD) are shown, although many cells in that group exhibited no MAPK activation.

Typically, MAPK is activated at low levels 1–2 h before GVBD (Fig. 2C, P3–15h), followed by robust MAPK activation due to a positive feedback loop between the MAPK cascade and MPF (33). IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was not sensitized in this population (Fig. 2B, low P-MAPK). This indicates that low MAPK activation is not sufficient to sensitize IP3Rs during maturation. In fact low MAPK activity correlated with decreased IP3-dependent Ca2+ release sensitivity (Fig. 1B, Prog. Late). Together these results show that IP3R sensitization occurs downstream of MPF activation and reaches maximal potentiation in fully mature eggs.

The IP3R Is Phosphorylated during Oocyte Maturation

An attractive potential mechanism to regulate IP3R sensitivity during oocyte maturation is phosphorylation, especially given the central role of kinase cascades in driving oocyte maturation. To test whether the IP3R is phosphorylated during maturation, oocytes were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and either left untreated (oocytes) or matured with progesterone (eggs) (Fig. 3A). Immunoprecipitation of the IP3R shows that it is phosphorylated in eggs but not oocytes (Fig. 3A). Several proteins that coimmunoprecipitate with the IP3R were also phosphorylated in eggs (Fig. 3A, Egg). Stripping and probing the blot with anti-IP3R antibodies confirmed that the IP3R was immunoprecipitated successfully from both cell types (Fig. 3A, WB).

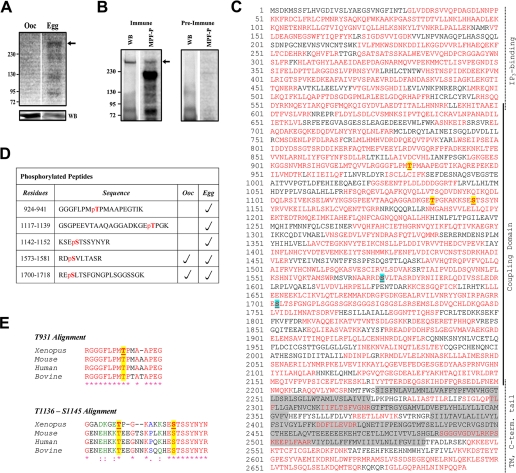

FIGURE 3.

Phosphorylation of the IP3R during oocyte maturation. A, cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and left untreated (oocytes, Ooc) or matured with progesterone (Egg). After overnight progesterone incubation cells that did not undergo GVBD were removed, and the remaining cells were incubated for 3 additional hours to ensure full maturation in the entire population (Egg). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. The blot was then probed with anti-IP3R antibody to confirm IP3R immunoprecipitation. B, the IP3R was immunoprecipitated from oocyte using either immune or pre-immune antibodies and the IP analyzed by Western using an anti-IP3R antibody (WB). Immunoprecipitates were incubated with MPF and [γ-32P]ATP, and the reaction was analyzed by autoradiography. C, map of the peptides detected following mass spectroscopy analysis of the IP3R. The immunoprecipitation was performed on at least 2000 cells, which typically produced a prominent band after staining with Simply Blue SafeStain. IP3R bands were excised from the gel, reduced, and alkylated with iodoacetamide and digested with trypsin or chymotrypsin. The peptide pool was analyzed by nano-liquid chromatography/MS/MS, and phosphopeptides were detected as discussed under “Experimental Procedures.” The map shown is for the egg IP with oocyte data yielding practically identical coverage. The red residues indicate peptides that were detected following the MS analysis, and the highlighted peptides indicate phosphorylated peptides. The shaded areas represent IP3R trans-membrane or lumenal domains. The domain structure of the IP3R is indicated on the right. D, details of the location and presence in oocytes or eggs of the phosphorylated peptides. The phosphorylated residue is indicated in red. E, sequence alignment of the regions in the type 1 IP3R surrounding the phosphorylated residues form different vertebrates.

Because the increased sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was observed only after MPF activation, we tested whether the IP3R is an MPF substrate. The IP3R was immunoprecipitated from oocytes and incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and MPF (Fig. 3B). Western blotting (WB) confirmed IP3R pulldown with immune but not pre-immune antibodies, and autoradiography (MPF-P) shows that the IP3R can be phosphorylated by MPF in vitro (Fig. 3B). Other proteins immunoprecipitated with the IP3R represent good substrates for MPF, however, we do not know their identity (Fig. 3B). These data show that the IP3R was phosphorylated in eggs and that it could act as an MPF substrate in vitro.

IP3R Phospho-peptide Mapping

To better define the role of phosphorylation in sensitizing the IP3R, we were interested in mapping the residues phosphorylated during maturation, because this would help identify the kinases responsible and outline possible functional implications based on which domains are phosphorylated. However, this is a daunting task given the large size of the IP3R (2693 residues). We tackled this problem using MS given its built-in high-throughput capabilities. The IP3R was immunoprecipitated from oocytes and eggs and analyzed by nano-liquid chromatography/MS/MS resulting in approximately ∼70% sequence coverage over the entire IP3R with the poorest coverage over the trans-membrane domain region (residues 2223–2534) (Fig. 3C). The coverage in the cytoplasmic domains was close to 75% (Fig. 3C). This to our knowledge is the first comprehensive phospho-peptide mapping effort of the endogenous IP3R.

The MS analysis identified five phospho-peptides. Two were detected in both oocytes and eggs, 1573–1581 and 1700–1718 (Fig. 3, C and D). The phosphorylated residues were mapped to Ser-1575 and Ser-1702 and localize to consensus PKA phosphorylation sites (RRX(S/T)Φ) (Fig. 3C). These residues correspond to Ser-1589 and Ser-1755 in the rat type 1 IP3R and have been shown to be phosphorylated by PKA, leading to potentiation of IP3R function (34–36). However, the fact that these sites are phosphorylated in both oocytes and eggs argues that phosphorylation at these PKA sites cannot solely explain the sensitization of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release in eggs. PKA is constitutively active throughout maturation except for a transient decrease in activity shortly after progesterone addition (37). This is consistent with our observation that both PKA sites are phosphorylated in oocytes and eggs.

The immunoprecipitation experiments were performed four times each on oocytes and eggs, and the MS analyses were undertaken at least six times for each of the oocyte and egg immunoprecipitates. In every case the peptides covering the PKA consensus sites were detected as phosphorylated in both oocytes and eggs, suggesting that this reflects the phosphorylation state of the majority of the IP3R population during maturation.

More interestingly MS analysis identified three phospho-peptides present only in eggs, 924–941, 1117–1139, and 1142–1152 (Fig. 3, C–E). The phosphorylated residues map to Thr-931, Thr-1136, and Ser-1145 (Fig. 3, C and D). Thr-931 and Thr-1136 localize within the minimal consensus phosphorylation sequence for MAPK and CDK ((S/T)P) (Fig. 3D). Sequence alignments show that both Thr-931 and Thr-1136 (Thr-945 and Thr-1155, respectively, in the rat IP3R) are conserved among different species, although in contrast to Thr-931, the residues surrounding Thr-1136 are poorly conserved (Fig. 3E). The Thr-931 site in Xenopus and other species perfectly fits the ERK consensus phosphorylation PX(S/T)P, and the Thr-1136 in Xenopus but not other vertebrates, fits the CDK consensus (S/T)PX(K/R) (Fig. 3E). The sequence surrounding Ser-1145 is well conserved (Fig. 3E), but has only weak similarities to the GSK3 consensus. Interestingly, however, it matches the mode III 14-3-3 consensus binding site, which requires phosphorylation to be functional (38). As was the case for PKA the phosphorylation state of peptides covering the MAPK/MPF consensus was consistent for all MS experiments performed.

The fact that Thr-931 and Thr-1136 localize within MAPK/MPF consensus sites raise the possibility that the IP3R is a target for these kinases during M-phase. However, the involvement of additional proline-directed kinases cannot be ruled out at this point. Nonetheless, IP3R1 phospho-peptide mapping during meiosis identified three novel sites (Thr-931, Thr-1136, and Ser-1145) phosphorylated in an M-phase-specific fashion. In addition, both PKA sites are phosphorylated during maturation.

IP3R Phosphorylation

To extend the MS data we biochemically tested the phosphorylation state of the IP3R during oocyte maturation by different kinases. We used a panel of phospho-specific antibodies that specifically recognize phosphorylated residues within the consensus site of the following kinases: PKC (P-Ser), PKA (P-Ser/Thr), and MAPK/CDK (both P-Ser and P-Thr) (Fig. 4A). Probing with the phospho-specific PKA antibody shows that the IP3R is phosphorylated on PKA consensus sites in both oocytes (O) and eggs (E) (Fig. 4A), thus confirming the MS data. No cross-reactivity with either the PKC or the P-Ser MAPK/CDK phospho-specific antibodies was observed (Fig. 4A). This suggests that, during maturation, the IP3R is not phosphorylated on PKC sites, nor is it phosphorylated on P-Ser sites within the minimal MAPK/CDK site ((S/T)P). Consistent with MS data the anti-phospho-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody reacts with the IP3R in eggs but not oocytes, supporting phosphorylation at Thr-Pro sites during maturation (Fig. 4A).

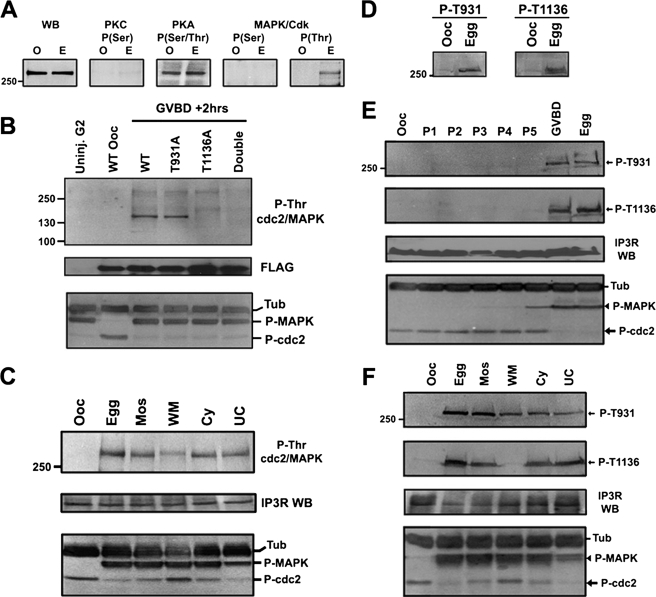

FIGURE 4.

In vivo analysis of IP3R phosphorylation during meiotic maturation. A, phosphorylation profile of immunoprecipitated endogenous IP3R from oocytes (O) and eggs (E) using phospho-specific antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated consensus for the indicated kinases. The first panel shows a Western blot using an anti-IP3R antibody (WB). B, oocytes were injected with mRNA encoding wild type or mutant FLAG-tagged coupling-domain region (565–1895) of the Xenopus IP3R. In the double mutant (Double) both Thr-931 and Thr-1136 were mutated to Ala. Cells were incubated for 3 days to allow expression of the constructs and lysates collected from oocytes or from cells 2 h after GVBD. Top panel, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody and probed with phospho-Thr MAPK/CDK substrate antibody; middle, the same blot was stripped and blotted with the anti-FLAG antibody; bottom, cell lysates were probed with phospho-MAPK and phospho-cdk1 antibodies as in Fig. 2C. C, modulation of the kinase cascade. Cells were untreated (Ooc) or matured with progesterone (Egg). Mos, cells were injected with MosRNA to activate the maturation kinase cascade. WM: cells were preinjected with Wee1 RNA to inhibit MPF activation before Mos injection. Cy: cells were injected with Cylin B RNA to directly activate MPF. UC: cells were pretreated with U0126 to inhibit the MAPK cascade before Cylcin B injection. Top panel, endogenous IP3R immunoprecipitated (IP) and probed with phospho-Thr MAPK/CDK substrate antibody; middle, the same blot was stripped and probed with anti-IP3R antibody; bottom, same as B. D, cell lysates from oocytes (Ooc) and eggs (Egg) were probed with phospho-specific antibodies that specifically recognize phosphorylated Thr-931 or Thr-1136. E, time course of IP3R phosphorylation. Cells were collected at different time points. P1–5 refers to 1–5 h after progesterone addition. Lysates were probed with the anti-phospho-Thr-931 and Thr-1136 antibodies (top two panels). Both Thr-931 and Thr-1136 are phosphorylated at GVBD. The same blot was stripped and probed with anti-IP3R antibody (IP3R WB). The activation state of MAPK and MPF was detected as in Fig. 2C. F, experimental setup is identical to C except that in this case the immunoprecipitates were probed with the anti-phospho-Thr-931 and Thr-1136 antibodies.

We then tested whether the P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody recognizes P-Thr-931 and/or Thr-1136 sites. We amplified and FLAG-tagged a portion of the IP3R1 coupling domain from a Xenopus oocyte cDNA library that contains both sites (residues 565–1895). In addition to the wild-type clone, we engineered three mutants: T931A, T1136A, and the double mutant (T931A/T1136A). Anti-FLAG IPs yield no product from uninjected cells 2 h after GVBD (Fig. 4B, Uninj G2), whereas the FLAG-tagged constructs were readily immunoprecipitated from injected oocytes at different stages of maturation (Fig. 4B, FLAG). In oocytes no reactivity with P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody was observed, whereas phosphorylation was detected in cells at 2 h after GVBD (Fig. 4B). This is consistent with the activation state of both MAPK and MPF (Fig. 4B, lower panel). The P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody also detected phosphorylation in the T931A mutant at GVBD+2 h. In contrast, all reactivity was lost in T1136A, and the double mutant at GVBD+2 h (Fig. 4B), showing that, within the coupling domain fragment, the P-MAPK/CDK antibody specifically recognizes P-Thr-1136.

Using the P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody, we then tested the phosphorylation state of the IP3R under conditions where the MAPK cascade and MPF were differentially activated (28). The entire cascade was activated by injecting oocytes with Mos RNA (see Fig. 1A). Alternatively, Wee1 RNA was injected prior to Mos to activate the MAPK cascade while maintaining MPF inhibition (Fig. 4C). Another approach was to activate the free Cdk1 pool by cyclin injection. Because of the positive feedback between MPF and the MAPK cascade, this leads to MAPK activation. Therefore, we also performed the cyclin RNA injections in the presence of the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 4C). The phosphorylation state of MAPK and MPF confirms that the kinases were modulated as expected (Fig. 4C, lower panel). Wee1-mediated inhibition of MPF was quite effective, whereas U0126 only partially inhibited MAPK activation (Fig. 4C, lower panel). Under these conditions, phosphorylation as detected by the P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody was greatly reduced in the Wee-Mos treatment, arguing that Thr-1136 is not phosphorylated in the absence of MPF activation (Fig. 4C). Phosphorylation was readily detected under all other conditions (Fig. 4C). Stripping and reprobing with anti-IP3R antibodies showed that the IP3R was immunoprecipitated to roughly equivalent levels in the different samples (Fig. 4C, IP3R WB).

Thr-931 and Thr-1136 Phospho-specific Antibodies

To specifically assess the phosphorylation state of Thr-931 and Thr-1136 during maturation, we generated phospho-specific antibodies to both residues. These antibodies recognize the egg but not oocyte IP3R (Fig. 4D), consistent with the phosphorylation state of these residues during maturation as detected by MS (Fig. 3).

A time course of oocyte maturation shows that both Thr-931 and Thr-1136 are initially phosphorylated at GVBD (Fig. 4E). This is despite the fact that MAPK activation is detectable at low levels at least 1 h before GVBD (Fig. 4E, lower panel).

We then differentially activated the MAPK cascade and MPF as described in Figs. 4C to test the effect on Thr-931 and Thr-1136 phosphorylation. The molecular interventions modulated the kinases as expected (Fig. 4F, lower panel). As was the case with the P-Thr MAPK/CDK antibody, Thr-1136 was phosphorylated under all conditions except when MPF was inhibited (Fig. 4F, Wee-Mos (WM)). This confirms that Thr-1136 is phosphorylated only when MPF is active. In addition, partial inhibition of MAPK activation with U0126 lowered the phosphorylation levels of Thr-931 as detected using the anti-phospho-Thr-931 antibodies (Fig. 4F, P-T931). Together the P-Thr MAPK/CDK and phosphor-specific Thr-931 and Thr-1136 antibody data, and the consensus sequence surrounding Thr-931 and Thr-1136, argue that MPF phosphorylates Thr-1136 and that Thr-931 is a potential MAPK target during maturation. The argument that Thr-931 is phosphorylated by MAPK is strengthened by the existence of a putative MAPK docking domain downstream of Thr-931 (residues 957–966) (39). However, we cannot conclusively rule out a potential role of other proline-directed kinases in Thr-931 and Thr-1136 phosphorylation.

Kinase-dependent Modulation of IP3R Function

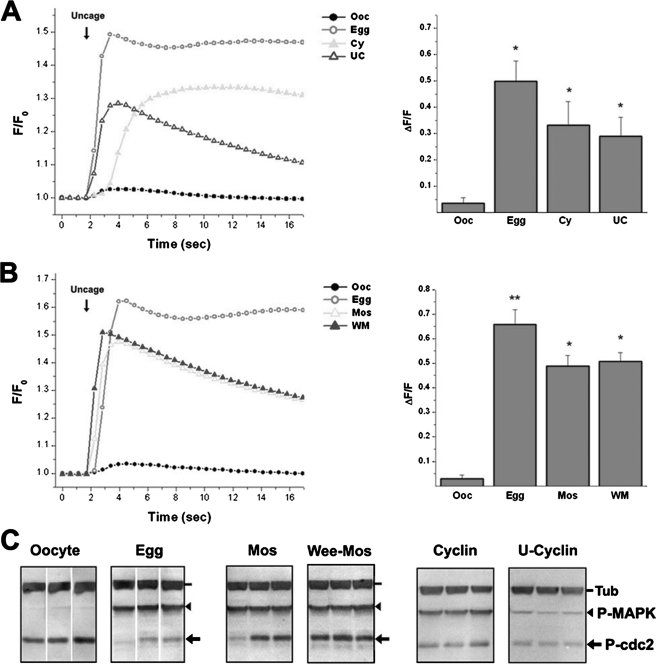

We then assayed Ca2+ release in response to a sub-threshold uncaging pulse under different conditions that differentially affect IP3R phosphorylation (Fig. 5). The uncaging pulse produces a small or no response in oocytes, whereas it results in robust Ca2+ release in eggs (Fig. 5). With the oocyte and egg as our reference points, we tested Ca2+ release in cells injected with cyclin B alone or pre-treated with U0126 (U-cyclin) (Fig. 5A). These treatments modulated MAPK and MPF as expected (Fig. 5C). Nonetheless, in both the cyclin or U-cyclin treatments IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was sensitized (Fig. 5A). This argues that MPF activation in the absence of significant MAPK activity is sufficient to sensitize the IP3R.

FIGURE 5.

Sensitization of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release following modulation of the maturation kinase cascade. Imaging conditions were as in Fig. 2A, and the modulation of the kinase cascade was as in Fig. 4, C and F. A and B, average traces after IP3 uncaging as indicated by the arrow. The error bars were omitted for clarity. Right panel, mean ± S.E. of the maximal Ca2+ signal (right panel). Data are from 11–30 cells per treatment, and the asterisk indicates significantly different datasets (p < 0.003 for A, and p < 0.028 for B). Oocytes (Ooc), eggs (Egg), cells injected with cyclin B RNA (Cy), cells pre-treated with U0126 before cyclin RNA injection (UC), cells injected with MosRNA (Mos), and cells injected with Wee1 RNA followed by MosRNA injection (WM). C, activation state of MAPK and MPF in the different groups as in Fig. 2C. Representative data from three individual cells are shown.

The same experimental approach was applied to cells injected with Mos or injected with Wee1 before Mos injection (Fig. 5B). Mos-injected cells robustly activate the MAPK cascade as expected with variable activation of MPF (Fig. 5C). This is because Mos-injected cells lost cellular integrity after GVBD, and thus had to be tested functionally shortly before or right at GVBD. Therefore, the differential activation level of MPF is reflective of the early time point at which cells were tested. In the case of the Wee-Mos protocol, MAPK was robustly activated in the absence of MPF activation (Fig. 5C). Following both the Mos and Wee-Mos protocols IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was also significantly sensitized (Fig. 5B). This argues that MAPK activation is sufficient for IP3R sensitization, at least under these conditions of high level MAPK activation following Mos injection.

Ca2+ Waves

Ca2+ signaling in the mature egg is characterized by a single sweeping Ca2+ wave that slowly spreads across the entire cell (9). Furthermore, wave propagation depends on functional IP3Rs, and a Ca2+ rise is sufficient to induce the Ca2+ wave (9, 13, 14). We therefore tested the ability of the same cell population analyzed in Fig. 5 to produce a Ca2+ wave in response to a sub-threshold uncaging pulse (Table 1). During maturation only eggs (40%) produce a Ca2+ wave (Table 1). Following kinase manipulation only cells injected with cyclin (∼42%) produce a Ca2+ wave (Table 1). These data argue that the ability of eggs to generate a Ca2+ wave requires both MAPK and MPF activation.

TABLE 1.

Treatment time course and epistasis

| Treatment | Ca2+ release | Wave |

|---|---|---|

| Time course | ||

| Oocyte | 10.5% (2/19) | 0% (0/19) |

| Prog. 3hrs | 8.3% (2/24) | 0% (0/24) |

| GVBD | 57.9% (11/19) | 0% (0/19) |

| Egg | 75% (15/20) | 40% (8/20) |

| Epistasis | ||

| Oocyte | 14.3% (4/28) | 0% (0/28) |

| Egg | 84.2% (32/38) | 50% (19/38) |

| Mos | 93.3% (28/30) | 0% (0/30) |

| Wee-Mos | 100% (22/22) | 0% (0/22) |

| Cyclin | 58.3% (7/12) | 41.7% (5/12) |

| U-Cyclin | 70.6% (12/17) | 0% (0/17) |

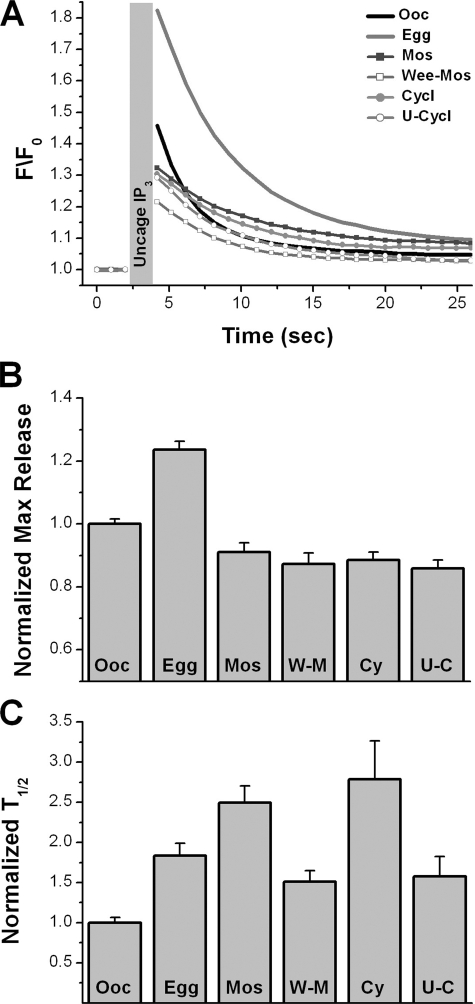

A critical feature of Ca2+ dynamics in eggs that reflects, and is dependent on, the increased sensitivity of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release during maturation is the decay rate of the Ca2+ signal (9, 11). The Ca2+ signal decays rapidly in oocytes but is more sustained in eggs (8). We have shown that the sustained Ca2+ signal in eggs requires functional IP3Rs (9) and that in modeling studies increased IP3 receptor affinity is sufficient to produce a sustained Ca2+ signal (11). Hence the rate of decay of the Ca2+ signal seems to provide a more sensitive measure of IP3R sensitization during maturation than maximal Ca2+ release as in Fig. 5. Furthermore, we postulate that the rate of Ca2+ signal decay reflects IP3R affinity, because the IP3R remains open for longer time periods as its affinity increases thus contributing to the sustained Ca2+ signal. This conclusion is supported by both physiological (9) and mathematical modeling studies (11). Using gradual IP3 uncaging during oocyte maturation we were able to assay the rate of Ca2+ signal decay independently of maximal Ca2+ release following manipulation of different kinase cascades as a measure of IP3R sensitization (Fig. 6). The kinase cascades were manipulated as in Fig. 5 and Ca2+ dynamics measured following gradual uncaging of IP3 using the 405 nm laser (Fig. 6A). Following this experimental paradigm hyperactivation of the MAPK cascade or MPF leads to smaller maximal Ca2+ release than even in oocytes (Fig. 6, A and B). This may be because the gradual IP3 increase leads to IP3R inactivation before a full Ca2+ release response is mounted, as observed in Fig. 1. Nonetheless, the rate of Ca2+ decay was significantly slower in cells where both MAPK and MPF were active following the injection of Mos or cyclin RNAs (Fig. 6C, Mos and Cy). Activation of either the MAPK cascade (Wee-Mos) or MPF (U0126-Cyclin), independently, results in a significantly faster decay rate compared with when both kinases are active (Fig. 6C, W-M and U-C). These data show that both the MAPK cascade and MPF need to be activated simultaneously to mediate the full sensitization of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. Although each kinase can separately mediate some aspects of sensitization, the full response, including increased maximal Ca2+ release, sustained Ca2+ signal, and the ability to mount Ca2+ waves, requires that both kinases be functional.

FIGURE 6.

Rate of Ca2+ signal decay as a measure of IP3R sensitization following modulation of the maturation kinase cascade. Imaging conditions were as in supplemental Fig. S1, and the modulation of the kinase cascade was as in Fig. 4 (C and F). A, average traces after gradual IP3 uncaging using the 405 nm laser as indicated by the gray bar. Error bars were omitted for clarity. B and C, maximal Ca2+ release levels immediately after the uncaging duration (B) and the rate of Ca2+ signal decay measured as the time required for half-maximal decay (T½) (C) in the different treatment groups. Mean ± S.E. data from 12–28 cells per treatment. Oocytes (Ooc), eggs (Egg), cells injected with cyclin B RNA (Cy), cells pre-treated with U0126 before cyclin RNA injection (U-C), cells injected with MosRNA (Mos), cells injected with Wee1 RNA followed by MosRNA injection (W-M).

DISCUSSION

IP3-dependent Ca2+ release is of fundamental importance to the fertilization-induced Ca2+ release that is responsible for egg activation and the initiation of development in vertebrates (1, 8, 12). Ca2+ release is functionally sensitized during oocyte maturation; however, the mechanisms controlling this sensitization remain unknown. This regulation of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release is not only critical in the context of meiosis and egg activation, but is also important in the progression of the mitotic cell cycle because of the similar regulation of the meiotic and mitotic G2/M transition.

Phosphorylation of the IP3R is likely to play a role in its sensitization, because several reports have shown that IP3R phosphorylation leads to increased Ca2+ release (40). Best characterized among IP3R kinases is PKA, which phosphorylates the type 1 receptor at two sites Ser-1589 and Ser-1755 (Ser-1575 and Ser-1703 in Xenopus IP3R1) (34). Phosphomimetic mutational analyses of the PKA sites in the SII-variant show that phosphorylation potentiates IP3-dependent Ca2+ release but suggest that phosphorylation at one site may preclude phosphorylation at the other site (36). Interestingly, in Xenopus oocytes, which express the SII-variant of the type 1 IP3R, we show that both PKA sites are phosphorylated throughout maturation. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that PKA activity is maintained at high levels in oocytes for prolonged time periods to maintain meiotic arrest, compared with the transient activation of PKA in cultured cells (36). Nonetheless, because PKA sites are phosphorylated in oocytes, PKA phosphorylation cannot explain IP3R potentiation during maturation. Another important implication of our results is that it is possible to induce additive functional potentiation of the IP3R beyond that conferred by PKA phosphorylation. This could be relevant under conditions in different cell types, where cAMP signaling coincides with other cascades to synergistically potentiate IP3-dependent Ca2+ release.

We identified three residues Thr-931, Thr-1136, and Thr-1145 that are specifically phosphorylated during oocyte maturation. Thr-931 and Thr-1136 are within proline-directed kinases consensus sites. Thr-931 lies within a region that perfectly matches the MAPK consensus phosphorylation site (PX(S/T)P), and Thr-1136 matches the cdk consensus ((S/T)PX(K/R)). Indeed our results show that phosphorylation of Thr-1136 depends on MPF activation, arguing that MPF is the Thr-1136 kinase. Although, phosphorylation levels of Thr-931 appear to track with the levels of MAPK, no phosphorylation at Thr-931 is observed 1 h before GVBD when MAPK is active.

Others have suggested that the IP3R may be modulated by Cdk1 and MAPK during the cell cycle (20, 21, 24). Phosphorylation of the IP3R in vitro by Cdk1 enhances IP3 binding affinity (21), and two residues, Ser-421 and Thr-799, that match the Cdk1 consensus were proposed to be directly responsible for Cdk1 action, because when they are mutated the increased IP3 affinity is abrogated (20, 21). Mathematical modeling shows that increased IP3 affinity would explain the potentiation of the IP3-dependent Ca2+ release in the egg and also contributes to shaping Ca2+ dynamics in eggs (11). We where therefore expecting that Ser-421 and Thr-799, which correspond to Ser-406 and Thr-784 Xenopus IP3R1, would be phosphorylated during maturation, because Cdk1 is activated and in the Xenopus sequence both sites perfectly fit the Cdk1 consensus. Surprisingly this was not the case, as peptides covering both residues (Ser-406 and Thr-784) were analyzed multiple times by MS and no phosphorylation was detected. Malathi et al. (20) have argued that both residues are phosphorylated during mitosis; however, basal phosphorylation during interphase was detected. These differences may be due to inherently different regulation of the IP3R during mitosis versus meiosis, or cell type-specific-directed phosphorylation.

During mouse oocyte maturation the IP3R1 has been shown to be phosphorylated in a stage-specific manner (41). Correlation studies argued that MAPK phosphorylation of the IP3R, potentially at Ser-436 (Ser-421 in Xenopus), during mouse oocyte maturation is important for sensitizing it (24). Ser-421 in the Xenopus receptor is not phosphorylated during maturation, showing that phosphorylation at this residue is not required for potentiation.

Our data also show that activation of both the MAPK cascade and MPF is required to fully potentiate IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. During the normal course of maturation full IP3R potentiation is achieved in eggs, that is ≥3 h after GVBD. However, Thr-931 and Thr-1136 are phosphorylated at GVBD. This shows that IP3R phosphorylation at these two residues is not sufficient per se to establish the full complement of maturation associated changes in IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. IP3R phosphorylation could be the triggering event that induces additional time-dependent alterations leading to remodeling of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release. One possibility is that phosphorylation could induce the association of IP3R-interacting proteins that in turn modulate IP3R function. In that context during our MS studies we have performed preliminary identification analyses of all the protein in the immunoprecipitates from oocytes or eggs, and identified (but have not yet validated) several candidates that interact with the IP3R in a maturation-specific manner. In addition, Ser-1145 when phosphorylated matches the binding consensus for 14-3-3 proteins (38), which could modulate IP3R function. Alternatively, phosphorylation could be the triggering event leading to physical clustering of IP3Rs, which is important for defining Ca2+ wave speed and dynamics in the egg (9, 10).

Together our data outline the role of IP3R phosphorylation in modulating Ca2+-release sensitivity during the meiotic cell cycle in preparation for fertilization. We show that the IP3R is specifically phosphorylated on at least three residues during the meiotic G2/M transition. This to our knowledge is the first comprehensive mapping of IP3R phosphorylation during cellular differentiation. Furthermore, our functional data show that full IP3R sensitization requires the activation of both the MAPK cascade and MPF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nigel Garret (Xenopus oocyte cDNA library) and Michael Hollman (pSGEM) for reagents.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM61829 from NIGMS.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- GVBD

- germinal vesicle breakdown

- MPF

- maturation-promoting factor

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- Ab

- antibody

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

- tandem MS

- WB

- Western blot

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stricker S. A. (1999) Dev. Biol. 211, 157–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ducibella T., Huneau D., Angelichio E., Xu Z., Schultz R. M., Kopf G. S., Fissore R., Madoux S., Ozil J. P. (2002) Dev. Biol. 250, 280–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozil J. P., Markoulaki S., Toth S., Matson S., Banrezes B., Knott J. G., Schultz R. M., Huneau D., Ducibella T. (2005) Dev. Biol. 282, 39–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machaca K., Qu Z., Kuruma A., Hartzell H. C., McCarty N. (2001) in Calcium Activates Chloride Channels (Fuller C. M. ed) pp. 3–39, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolmetsch R. E., Lewis R. S., Goodnow C. C., Healy J. I. (1997) Nature 386, 855–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson M. T., Cheng H., Rubart M., Santana L. F., Bonev A. D., Knot H. J., Lederer W. J. (1995) Science 270, 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charbonneau M., Grey R. D. (1984) Dev. Biol. 102, 90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machaca K. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Jouni W., Jang B., Haun S., Machaca K. (2005) Dev. Biol. 288, 514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machaca K. (2004) Dev. Biol. 275, 170–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ullah G., Jung P., Machaca K. (2007) Cell Calcium 42, 556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki S., Shirakawa H., Nakada K., Honda Y. (1993) Dev. Biol. 158, 62–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larabell C., Nuccitelli R. (1992) Dev. Biol. 153, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuccitelli R., Yim D. L., Smart T. (1993) Dev. Biol. 158, 200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terasaki M., Runft L. L., Hand A. R. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1103–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parys J. B., McPherson S. M., Mathews L., Campbell K. P., Longo F. J. (1994) Dev. Biol. 161, 466–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba K., Kado R. T., Jaffe L. A. (1990) Dev. Biol. 140, 300–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara T., Nakada K., Shirakawa H., Miyazaki S. (1993) Dev. Biol. 156, 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehlmann L. M., Kline D. (1994) Biol. Reprod. 51, 1088–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malathi K., Kohyama S., Ho M., Soghoian D., Li X., Silane M., Berenstein A., Jayaraman T. (2003) J. Cell. Biochem. 90, 1186–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malathi K., Li X., Krizanova O., Ondrias K., Sperber K., Ablamunits V., Jayaraman T. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 6205–6210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santella L., Ercolano E., Lim D., Nusco G. A., Moccia F. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim D., Ercolano E., Kyozuka K., Nusco G. A., Moccia F., Lange K., Santella L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42505–42514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee B., Vermassen E., Yoon S. Y., Vanderheyden V., Ito J., Alfandari D., De Smedt H., Parys J. B., Fissore R. A. (2006) Development 133, 4355–4365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Josefsberg Ben-Yehoshua L., Lewellyn A. L., Thomas P., Maller J. L. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 664–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perdiguero E., Nebreda A. R. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 733–737 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villmann C., Bull L., Hollmann M. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 7634–7643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun L., Machaca K. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165, 63–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edmondson R. D., Vondriska T. M., Biederman K. J., Zhang J., Jones R. C., Zheng Y., Allen D. L., Xiu J. X., Cardwell E. M., Pisano M. R., Ping P. (2002) Mol. Cell Proteomics 1, 421–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller A., Nesvizhskii A. I., Kolker E., Aebersold R. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74, 5383–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nesvizhskii A. I., Keller A., Kolker E., Aebersold R. (2003) Anal. Chem. 75, 4646–4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nebreda A. R., Ferby I. (2000) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 666–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machaca K., Haun S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38710–38715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferris C. D., Cameron A. M., Bredt D. S., Huganir R. L., Snyder S. H. (1991) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 175, 192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Li W. H., Yule D. I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45811–45817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Li W. H., Joseph S. K., Yule D. I. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46242–46252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maller J. L., Butcher F. R., Krebs E. G. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 579–582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coblitz B., Wu M., Shikano S., Li M. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 1531–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharrocks A. D., Yang S. H., Galanis A. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patterson R. L., Boehning D., Snyder S. H. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 437–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jellerette T., Kurokawa M., Lee B., Malcuit C., Yoon S. Y., Smyth J., Vermassen E., De Smedt H., Parys J. B., Fissore R. A. (2004) Dev. Biol. 274, 94–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liman E. R., Tytgat J., Hess P. (1992) Neuron 9, 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.