Abstract

A series of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon carbohydrate surfactants with different headgroups (i.e., gluco-, galacto- and maltopyranoside) and (fluorinated) alkyl tails (i.e., C7 and C14 to C19) was synthesized to investigate trends in their cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity, and how surfactant-lipid interactions of selected surfactants contribute to these two measures of biocompatibility. All surfactants displayed low cytotoxicity (EC50 = 25 to > 250 μM) and low haemolytic activity (EC50 = 0.2 to > 3.3 mM), with headgroup structure, tail length and degree of fluorination being important structural determinants for both endpoints. The EC50 values of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon glucopyranoside surfactants displayed a “cut-off” effect (i.e., a maximum with respect to the chain length). According to steady-state fluorescence anisotropy studies, short chain (C7) surfactants partitioned less readily into model membranes, which explains their low cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity. Interestingly, galactopyranosides were less toxic compared to glucopyranosides with the same hydrophobic tail. Although both surfactant types only differ in the stereochemistry of the 4-OH group, hexadecyl gluco- and galactopyranoside surfactants had similar apparent membrane partition coefficients, but differed in their overall effect on the phase behaviour of DPPC model membranes, as assessed using steady-state fluorescence anisotropy studies. These observations suggest that highly selective surfactant-lipid interactions may be responsible for the differential cytotoxicity and, possible, haemolytic activity of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon carbohydrate surfactants intended for a variety of pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.

Keywords: Cytotoxicity, Haemolytic activity, Surfactant-lipid interactions, DPPC, Fluorescence anisotropy

1. Introduction

Self-assembled supramolecular nano- and microstructures (such as liposomes, microemulsions and microbubbles) of simple, single-tailed carbohydrate surfactants with a hydrocarbon or a partially fluorinated hydrophobic tail are of interest for a number of pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Hydrocarbon carbohydrate surfactants have been studied as solubilising agents in aqueous formulations and offers several advantages compared to classical polyoxyethylene-based surfactants, including comparatively high purity, biodegradability and production from renewable sources [1, 2]. Fluorinated, carbohydrate-based surfactants are of interest for pharmaceutical applications, such as novel perfluorocarbon compound (PFC)-based drug delivery systems [3-5]. In particular reverse water-in-PFC (micro-)emulsions are investigated for the pulmonary administration to the diseased lung [4-6]. These reverse emulsions allow the delivery of a well defined dose of pharmacological agents directly to the diseased lung via the airways, for example during liquid ventilation [6, 7], without adversely impairing gas exchange in the lung [4-6]. Because of this broad range of pharmaceutical and biomedical applications, there is considerable interest in developing new, biocompatible carbohydrate-based surfactants.

Despite their potential use in a range of pharmaceutical application, structure-toxicity relationships of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon carbohydrate surfactants in general and simple gluco-, galacto- and maltopyranoside surfactants in particular are poorly developed, especially in mammalian systems. Only a few reports have investigated the toxicity and haemolytic activities of hydrocarbon [1, 2, 8, 9] and fluorocarbon surfactants [10-15] with carbohydrate headgroups. Limited studies of the effect of different carbohydrate surfactants on model membranes [16] and the in vitro haemolytic activity [2] suggest that the headgroup and the hydrophobic tail are both important structural determinants of surfactant-lipid interactions and, thus, toxicity and haemolytic activity. There is also evidence that an increasing degree of fluorination reduces both toxicity and haemolytic activity compared to the corresponding hydrocarbon surfactant [10-15]. However, it is unclear if carbohydrate surfactants also display a “cut-off effect” in biological activities (e.g., a maximum in activity based on chain length) that is characteristic of many nonionic surfactants [17]. Little is also known about the interaction of carbohydrate surfactants with model membranes and biological lipid assemblies. This is an important gap in our knowledge because surfactants that have a high affinity for lipid membranes may adversely affect membrane permeability, fluidity, curvature and, ultimately, membrane function.

Most of the above mentioned studies are limited to a comparatively small number of commercially available carbohydrate surfactants, thus limiting efforts to understand if general trends in cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity are related to surfactant-lipid interactions. Here we investigate the cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity of a series of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon gluco-, galacto- and maltopyranoside surfactants in vitro to identify structural factors (e.g., chemical structure of the headgroup, length and degree of fluorination of the hydrophobic tail) influencing both measures of biocompatibility. Subsequently, the membrane partitioning behaviour of selected surfactants is investigated to aid in our understanding of general trends in cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Methods

The long-chain hydrocarbon starting material 1a and 1b were purchased from TCI Chemicals (Portland, Oregon, USA). Pentaacetyl-β-D-glucopyranose (4), the long chain alkyl alcohols 3 and anhydrous dichloromethane were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, New Jersey, USA). Perfluorinated iodides were purchased from Oakwood Chemical Co. (West Columbia, South Carolina, USA). Heptyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (β–13a) was purchased from EMD Biosciences Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). The synthesis and characterization of all other carbohydrate surfactants (Scheme 1) is described in detail in the supporting material. L-α-Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC, >99%) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipid (Alabaster, AL, USA); 1,6-Diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH, >99%), was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Chloroform (>99.9%) and tetrahydrofuran (THF, >99.9%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Deionized ultrafiltered water (DIUF) was obtained using a MILLI-Q system (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA).

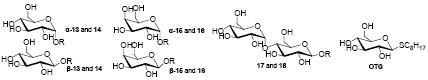

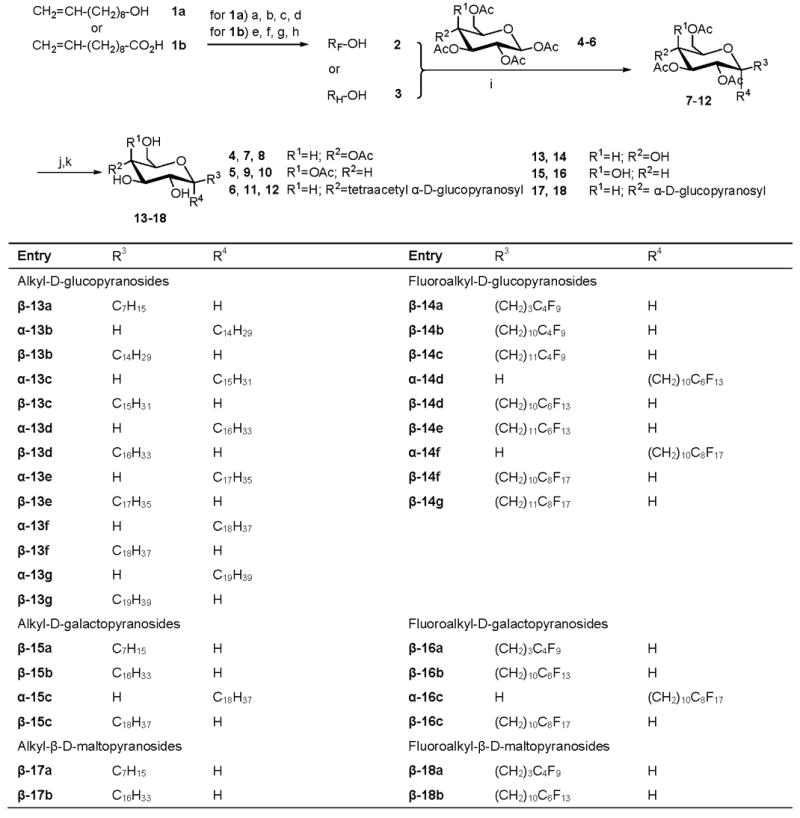

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and chemical structure of perfluoroalkyl and alkyl glycosides. (a. DMAP, Ac-Cl, pyridine, DCM; b. F(CF2)mI, AIBN; c. HI (55%), Zn, C2H5OH; d. CH3OH, KOH; e. CH3OH, PTSA, toluene; f. F(CF2)mI (m=4,6 or 8), AIBN; g. HI (55%), Zn, C2H5OH; h. LiAlH4, anhydrous ether, ambient temperature; i. BF3/OEt2 (48%), anhydrous DCM (α-anomer: 0°C for 20 min, then 30°C for 10h; β-anomer: 0°C for 2h, then warmed to ambient temperature); j. MeONa/MeOH, 0°C to ambient temperature; k. Dowex®50W×8-100 ion-exchange resin).

2.2. Assessment of cytotoxicity

2.2.1. Cancer cell line

The B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line (Interlab Cell Line Collection, Milano, Italy) was selected from a panel of cancer cell lines used for testing in our laboratory. The cell line was grown in D-MEM medium (Sigma, Czech Republic) supplemented with 10% of fetal calf serum (Gibco, Czech Republic), 50 mg L-1 penicillin, 50 mg L-1 streptomycin, 100 mg L-1 neomycin, and 300 mg L-1 L-glutamine as reported previously [18, 19]. Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

2.2.2. MTT-based cytotoxicity test

The MTT assay [20, 21] was used to assess the cytotoxicity of the glucopyranosides in cells in the exponential growth phase. In short, cells were seeded on 96-well flat-bottom microplates at the density 2.5–3.0 × 104 per mL, 100 μL per well, and allowed to grow for 16 to 24 h in culture medium. The tested compounds were first dissolved in DMSO (Sigma, Czech Republic) and than in sterile PBS. Final concentrations of DMSO in samples were below 1%. PBS with DMSO (1 and 5%) served as control. No cytotoxicity of 1% DMSO in PBS was observed. Glycopyranosides dissolved in sterile PBS (total volume of 20 μL) were added to each well and the cytotoxic effect was evaluated after 24 h of exposure over a concentration range from 1 μM to 250 μM using the MTT assay. Octylthioglucoside (Roche, Czech Republic) was used as a positive control.

MTT (Sigma Chemical Co., Czech Republic) was dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 5 mg mL-1 and sterilized by filtration. MTT solution was added into all wells of 96-well flat-bottom microplates with cells in a dose of 20 μL per well. The plates were incubated for 3 h. To enhance the dissolution of dark-purple crystals of formazan, 110 μL of 10% SDS in PBS (final pH 5.5) were added to all wells. The microtiter plates were stored in a light-tight box at room temperature, evaluated on the next day using a well-plate spectrophotometer reader Synergy 2 (BioTek, USA) at 540 nm and the EC50 (i.e. the molar concentration which produces 50% of the maximum possible inhibitory response) values were calculated from the dose response curves. All experiments were performed in triplicate and EC50 values were calculated using GraphPad PRISM V.4.00 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

2.2.3. Haemolytic activity

Rabbit red blood cells (2% in PBS) were used to perform standard haemolytic tests in both PBS and PBS containing 20% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). The surfactants were tested in concentration range extending from 7 μM to 3.3 mM. The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO and added into PBS. Maximal final concentration of DMSO in PBS was 5% for 20 mM concentration of tested compound. This concentration of DMSO does not cause any haemolysis in control red blood cells. After 2 h incubation of red cells with a particular compound at 37 °C, the released haemoglobin was separated from red blood cells by centrifugation (700g, 10 min, three washes) and quantified using a well-plate spectrophotometer reader EL 800 (BioTek, USA) at 540 nm. Data are expressed as the lowest concentration of surfactant causing 50% haemolysis.

2.3. Fluorescence anisotropy studies

2.3.1. Preparation of DPH-labelled DPPC vesicles

Multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) of DPPC containing increasing concentration (0-20 μM) of carbohydrate surfactants and DPH with the lipid-to-DPH molar ratio of 500:1 were prepared [22]. In short, 250 μL of a DPPC solution (1 mM in chloroform), 2 μL of a DPH solution (0.25 mM in THF) and the appropriate volume of a solution of carbohydrate surfactant β-13a, β-13d or β-15b (1 mM in chloroform) were mixed well before removing the solvent using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at 30 °C. After being dried under a high vacuum for 2 h to remove solvent traces, the resulting films were hydrated with 1 mL of ultra-pure water well above the phase transition temperature of DPPC (T > 50 °C) for 1 h. Subsequently, the liposome suspensions were vortexed for 3 min to uniformly disperse the MLVs. Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were obtained from the MLVs by extruding the suspension 15-times through a double-stacked polycarbonate membrane filter (pore size: 100 nM) using a LiposoFast extruder (Avestin Inc., British Columbia, Canada) at 50 °C. The resulting lipid dispersions were stored at room temperature and used within 24 h of preparation. The final working samples were prepared by diluting the 100 μL of the LUV suspensions with 2400 μL of ultra-pure water.

2.3.2. Measurement of stead-state anisotropy

Steady-state DPH fluorescence anisotropy experiments with the final working solutions were carried out using a LS55 Luminescence Spectrometer from PerkinElmer (Shelton, CT, USA) as described previously [22]. In short, the cuvette chamber was thermally controlled using a PerkinElmer PTP-1 Peltier System (Shelton, CT, USA). The solutions were mixed continuously with a small magnetic stir bar at low speed. The steady-state DPH anisotropy within the DPPC bilayer was determined at λex = 350 nm and λem = 452 nm with an excitation and emission slit width of 10 nm. For the fluorescence experiment, the samples were equilibrated at 50 °C for 15 min and subsequently cooled to 20 °C with a rate of 0.2 °C/min. DPH anisotropy values <r> were calculated from equation 1 as follows,

| (1) |

where IVV and IVH are the values of the fluorescence intensity measured with both polarizers in vertical (VV) orientations or with the excitation polarizer in vertical and emission polarizer in horizontal position (VH), respectively. G is a correction factor for differences in sensitivity of the detection system for vertically and horizontally polarized light. Tm, the temperatures at the midpoint of the phase transition were determined from plots of absolute fluorescence anisotropy as a function of temperature [22]. All fluorescence experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.3.3. Calculation of apparent partition coefficients

The partition coefficients K of the surfactant between DPPC bilayers and the aqueous phase were calculated based on shifts in melting temperature [22, 23] according to the equation

| (2) |

where Tm,0 represents the phase transition temperature without additives and ΔTm (i.e., Tm − Tm,0) is the changes of the melting temperature according to DPPC vesicles without additives. ΔHm is the enthalpy change associated with the phase transition (31.38 kJ · mol-1) [24] and R is the gas constant (8.314 J · K-1 · mol-1). CL and CA denote the total lipid concentration and the concentration of additive (surfactant), respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis

To further explore structure-toxicity relationships of simple, single-tailed carbohydrate surfactants and to investigate their interaction with (model) membranes, we synthesized and characterized a series of 34 α- and β-gluco-, galacto- and maltopyranosides and 4 mixtures containing the α- and β-anomers of the respective surfactants (Scheme 1). All surfactants were synthesized from a fluorinated alcohol 2 and the appropriate peracetylated carbohydrate (4-6) as described previously for β-glucopyranoside surfactants [15]. In short, the fluorinated alcohols 2 were prepared from 9-decen-1-ol (1a) or undecenoic acid (1b) in four steps as described earlier [15, 19]. Subsequently, peracetylated gluco- (7 and 8), galacto- (9 and 10) or maltopyranosides (11 and 12) were obtained by reacting the fluorinated alcohols 2 (or the corresponding hydrocarbon analogues 3) with the corresponding peracetylated β-D-gluco- (4), β-D-galacto- (5) or β-maltopyranosides (6) using BF3·Et2O as catalyst [13, 25-28]. The respective α- and β-anomers were obtained by controlling the reaction temperature and time (β-anomers: < 5 °C and < 3 h; α-anomers: 30 °C and 10 h). In the final step of the synthesis, the (F-)alkylated peracetylated carbohydrates 7–12 were deacetylated using NaOMe in absolute methanol, followed by neutralization with Dowex® 50W×8-100 ion exchange resin [27]. The surfactants were obtained in moderate-to-good yields and are >95% pure. Molecular structures of nonadecyl α-D-glucopyranoside (α-13g) obtained by geometry optimization using the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method or crystal structure analysis are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of nonadecyl α-D-glucopyranoside (α-13g). (A) 3D Structure obtained by geometry optimization using the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method [15]. (B) Crystal structure showing the atom-labelling scheme. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

3.2. Cytotoxicity in the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line

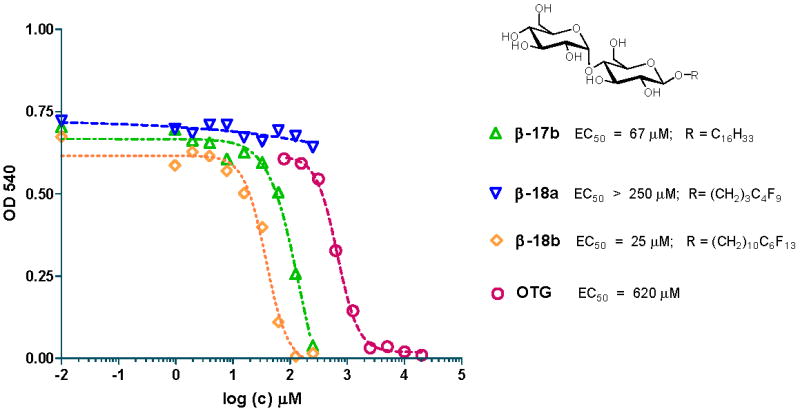

An initial cytotoxicity assessment of all 34 alkyl- and fluoro-alkyl carbohydrate surfactants (plus 4 mixtures of α- and β-anomers) was performed using the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line to assess their overall biocompatibility and gain insights into structure-toxicity relationships. The cytotoxicities of the test compounds, expressed as EC50 values, are summarized in Table 1. Representative cytotoxicity curves for maltopyranosides surfactants β-17b, β-18a and β-18b are presented in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Assesment of cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity of partially fluorinated carbohydrate surfactants and their hydrocarbon analogues in B16F10 cell line.a

| Entry | Structure of tails | Cytotoxicity EC50 (μM) | Haemolytic activity EC50 (mM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| without serum | 20 % serum | |||

| Alkyl glucopyranosides | ||||

| α-13b | C14H29 | 53 | 2.5 | >3.3 (30%) |

| α-13c | C15H31 | 67 | >3.3 (20%) | >3.3 |

| α-13d | C16H33 | 70 | >3.3 (20%) | >3.3 |

| α-13e | C17H35 | 37 | >3.3 (25%) | >3.3 |

| α-13f | C18H37 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| α-13g | C19H39 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-13a | C7H15 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-13bb | C14H29 | 41 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| β-13cb | C15H31 | 38 | 0.8 | 2.5 |

| β-13db | C16H33 | 50 | >3.3 (30%) | >3.3 |

| β-13eb | C17H35 | 38 | 2.5 | >3.3 (5%) |

| β-13fb | C18H37 | 32 | >3.3 (10%) | >3.3 |

| β-13gb | C19H39 | 100 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| (α+β)-13bc | C14H29 | 62 | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| (α+β)-13gd | C19H39 | >250 | >3.3 (5%) | >3.3 |

| Perfluoroalkyl glucopyranosides | ||||

| α-14d | (CH2)10C6F13 | 47 | >3.3 (5%) | >3.3 |

| α-14f | (CH2)10C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-14a | (CH2)3C4F9 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-14bb | (CH2)10C4F9 | 32 | >3.3 (10%) | >3.3 (10%) |

| β-14cb | (CH2)11C4F9 | 32 | 2.5 | >3.3 |

| β-14db | (CH2)10C6F13 | 52 | >3.3 (25%) | >3.3 |

| β-14eb | (CH2)11C6F13 | 30 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-14fb | (CH2)10C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-14gb | (CH2)11C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| (α+β)-14ae | (CH2)3C4F9 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| (α+β)-14gf | (CH2)11C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| Alkyl galactopyranosides | ||||

| α-15c | C18H37 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-15a | C7H15 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-15b | C16H33 | >250 | >3.3 (40%) | >3.3 |

| β-15c | C18H37 | >250 | >3.3 (20%) | >3.3 |

| Perfluoroalkyl galactopyranosides | ||||

| α-16c | (CH2)10C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 (10%) | >3.3 |

| β-16a | (CH2)3C4F9 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-16b | (CH2)10C6F13 | >250 | >3.3 (20%) | >3.3 (5%) |

| β-16c | (CH2)10C8F17 | >250 | >3.3 (5%) | >3.3 |

| Alkyl maltopyranosides | ||||

| β-17a | C7H15 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-17b | C16H33 | 67 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Perfuoroalkyl maltopyranosides | ||||

| β-18a | (CH2)3C4F9 | >250 | >3.3 | >3.3 |

| β-18b | (CH2)10C6F13 | 25 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Positive control | ||||

| OTG | Octylthioglucoside | 620 | 0.5 | 3 |

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic effect of maltopyranosides β-17b, β-18a and β-18b in the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line. B16F10 cells were exposed for 24 h to the respective carbohydrate surfactants at the concentrations shown and assessed for MTT activity as described under experimental. A representative hydrocarbon surfactant, octylthioglucoside (OTG), is shown for comparison.

The C14 to C17 hydrocarbon α- (α-13b-e) and β-glucopyranosides (β-13b-e) showed mild cytotoxicity, with EC50 values in the range of 37-70 μM. The C18 and C19 α-glucopyranosides α-13f and α-13g did not show a cytotoxic effect in the concentration range investigated, whereas the corresponding β-glucopyranosides β-13f and β-13g were moderately toxic. Mixtures of α- and β-glucopyranosides 13b and 13g had cytotoxicities that were similar to the toxicity of the pure α- and β-anomers. The cytotoxicity of β-glucopyranosides with short C7 alkyl (β-13a) or fluorinated alkyl chains (β-14a) was insignificant and comparable to the positive control, octylthioglucoside (EC50 > 250 μM). α- and β-glucopyranosides with partially fluorinated C14 to C17 alkyl chains (α-14d and β-14b-e) had EC50 values that were comparable to the corresponding hydrocarbon derivatives. Glucopyranosides with the highest degree of fluorination (i.e., α-14f and β-14f-g) were not cytotoxic, with EC50 values > 250 μM, whereas the hydrocarbon C18 and C19 β-glucopyranosides β-13f and β-13g were moderately cytotoxic (EC50 values of 32 and 100 μM, respectively).

In contrast to the gluco- and maltopyranosides (see below), all surfactants based on α- (α-15c and α-16c) or β-galactose (β-15a-c and β-16a-c) were nontoxic, with EC50 values > 250 μM. This is a surprising observation considering the structural similarity between the gluco- and galactopyranosides.

The EC50 values of β-maltopyranosides with C16 alkyl (β-17b) and C16 fluoroalkyl chains (β-18b) were 67 and 25 μM, respectively, which is within the range observed for the structurally related C16 glucopyranosides. β-Maltopyranosides with a short C7 alkyl (β-17a) or C7 fluoroalkyl chain (β-18a) were nontoxic within the concentration range investigated (EC50 > 250 μM), which is also comparable to the EC50 values observed with analogous C7 gluco- and galactopyranosides.

3.3. Haemolytic activity

Much higher concentrations of the surfactants were generally needed to induce haemolysis. In fact, most carbohydrate surfactants displayed no in vitro haemolytic activity, with EC50 values >3.3 mM (Table 1). Only a few surfactants were slightly haemolytic, with EC50 ranging from 0.8 to 2.5 mM. This moderate haemolytic activity was suppressed by the addition of serum, which is known to have a protective effect on cell membranes in the presence of surfactants. No correlation was observed between the haemolytic activity and the cytotoxicity.

The alkyl α-glucopyranosides α-13b-e showed a slight indication of haemolysis at 3.3 mM concentrations, whereas the long-chain derivatives α-13f and α-13g were not haemolytic in the concentration range under investigation. This is in contrast to the alkyl β-glucopyranosides β-13b and β-13c, which appeared to have slightly more haemolytic activity compared to the corresponding α-glucopyranosides. The C7 glucopyranosides β-13a and β-14a were essentially nonhaemolytic at concentrations below 3.3 mM. In contrast, the positive control, octylthioglucoside, showed significant haemolytic activity in the concentration range investigated, with an EC50 of 0.5 mM. Partially fluorinated α- and β-glucopyranosides 14 displayed slightly lower haemolytic activities compared to their hydrocarbon analogues.

Hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon surfactants based on α- and β-galactose (α-15c or β-15a-c and α-16c or β-16a-c, respectively) were slightly less haemolytic compared to analogous glucopyranosides. In contrast to the corresponding β-glucopyranosides [15], the partially fluorinated tail conveyed little-to-no protection against haemolysis.

Like other C7 carbohydrate surfactants, both β-maltopyranoside C7 surfactants (β-17a and β-18a) were nonhaemolytic, whereas the C16 maltopyranoside surfactant β-17b was the most haemolytic compound under investigation. The high haemolytic activity of β-17b was substantially suppressed by addition of serum. Introduction of a partially fluorinated C16 chain (β-18b) suppressed haemolytic activity by more than one order of magnitude. The relatively high haemolytic activity of β-17b suggests a specific effect of this surfactant on red cell membranes compared to other carbohydrate surfactants.

3.4. Assessment of membrane partition behaviour using steady-state fluorescence anisotropy

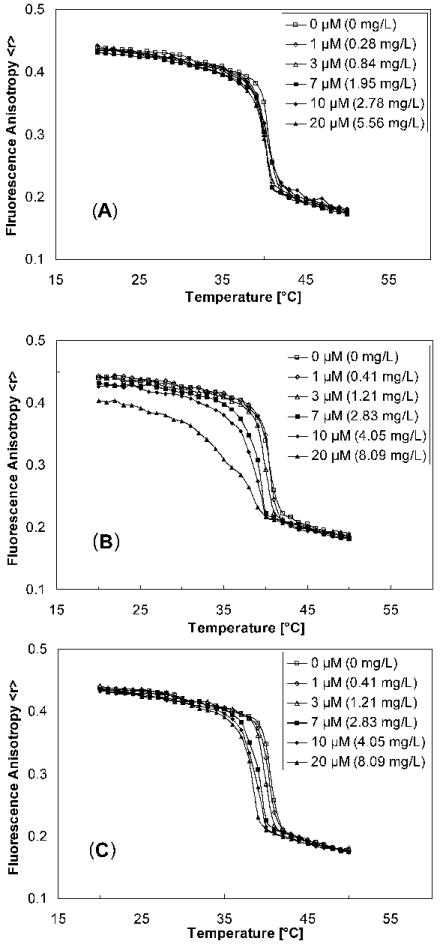

The partitioning of carbohydrate surfactants into model or cell membranes is expected to alter membrane properties, such as fluidity and/or curvature. These changes may explain the trends in cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity. To test this hypothesis, we studied the effect of three hydrocarbon surfactants, β-13a, β-13d and β-15b, on dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) model membranes using 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) fluorescence anisotropy. Measurements of the fluorescence anisotropy <r> (equation 1) are extensively used to study the effect of small molecules on membrane behaviour by assessing changes in the rotational diffusion of the fluorophore (i.e., DPH) that are thought to correlate with the fluidity of the membrane [29].

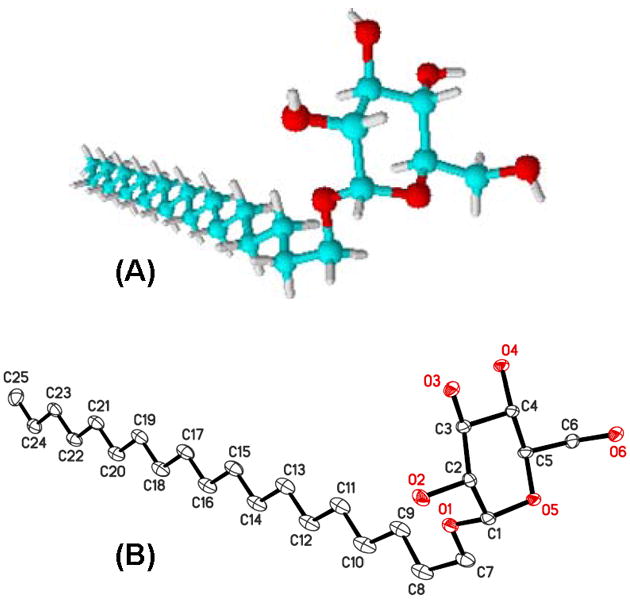

Figure 3 shows the temperature-dependent change in the fluorescent anisotropy <r> of DPH-labelled DPPC bilayers for selected concentrations of the respective carbohydrate surfactant. Upon cooling, the DPPC model membrane displayed a characteristic, sharp change in the fluorescence anisotropy. This change in the fluorescence anisotropy indicates a significant change in the fluidity of the bilayer due to the transition from the liquid-crystalline to the gel-phase of DPPC. The midpoint of this change in <r> corresponds to the major phase transition temperature (Tm) of DPPC. The width of the phase transition can be calculated from the on- and offset of the change in <r>. Similar to other small molecules, Tm decreased and the transition width increased with increasing concentrations of all three carbohydrate surfactants. The increase in the transition width was especially significant for the C16 glucopyranoside β-13d.

Figure 3.

Temperature-dependent changes of DPH fluorescent anisotropy in DPPC bilayers for selected concentrations of carbohydrate surfactants β-13a (A), β-13d (B) or β-15b (C) respectively. Samples containing 10 μM of DPPC were cooled from 50 to 20 °C at a rate of 0.2 °C/min. The excitation and emission wavelengths are 350 nm and 452 nm respectively. The excitation and emission slit widths are both 10 nm.

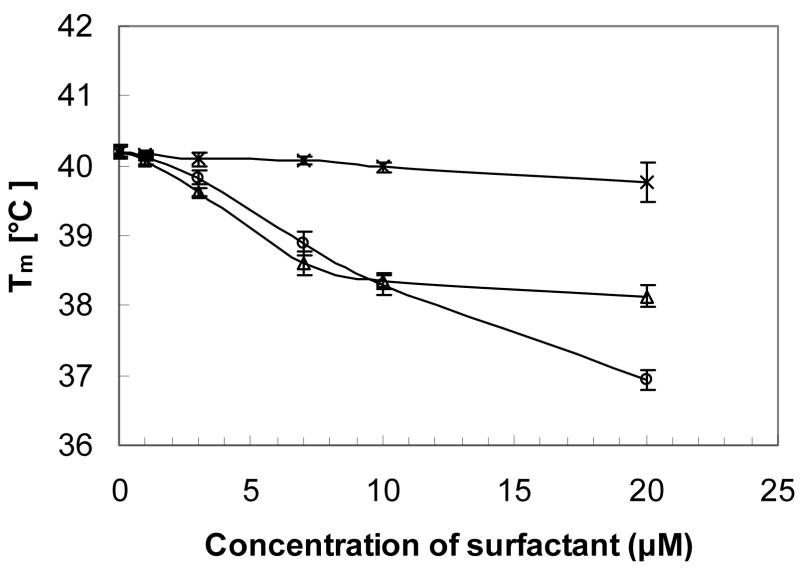

As shown in Figure 4, the decrease in Tm differed significantly between the three surfactants. The Tm of hexadecyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13d) decreased linearly over the entire concentration range investigated (0 to 20 μM), whereas the structurally similar hexadecyl β-D-galactopyranoside (β-15b) displayed a linear decrease in Tm up to a surfactant concentration of 7 μM and an approximately constant Tm at concentrations ≥ 10 μM. In contrast, the short-tailed surfactant, heptyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13a), decreased the phase transition temperature of DPPC only slightly over the same concentration range. The membrane partition coefficients calculated using equation 2 from the depression of Tm increased in the order heptyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13a, 4.61×104, R2 = 0.98) ≪ hexadecyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13d, 2.78×105, R2 = 0.99) < hexadecyl β-D-galactopyranoside (β-15b, 5.15×105, R2 = 0.99).

Figure 4.

Tm as a function of the increasing concentration of carbohydrate surfactants β-13a (×), β-13d (◊) or β-15b (Δ). Tm, the temperatures at midpoint of the phase transition, was determined from plots of absolute fluorescence anisotropy values as a function of temperature. All fluorescence experiments were carried out at least in triplicate.

4. Discussion

In the present study we investigate general trends in the cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity of a series of 34 hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon carbohydrate surfactants. Subsequently, the membrane partition behaviour of selected surfactants was investigated in vitro to assess if surfactant-lipid interactions play a role in the observed trends in cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity.

4.1. Cytotoxicity in cells in culture – structure-toxicity relationships

Only limited information about the cytotoxicity of carbohydrate surfactants in mammalian cell culture models have been published. Several studies have reported that partially fluorinated, carbohydrate based surfactants are not toxic at high micromolar to low millimolar concentrations, whereas the corresponding hydrocarbon analogues display considerable toxicity [10-14]. Unfortunately, these studies typically did not report an EC50 value, which makes it difficult to investigate structure-toxicity relationships and to compare studies using different cell lines. Furthermore, these studies investigated only a few surfactants with glucose, galactose or maltose headgroups. Therefore, we determined the cytotoxicity of all 34 surfactants using the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line (Table 1 and Figure 2) to investigate structure-toxicity relationships.

The most intriguing finding of this study is that the EC50 values of the hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon glucopyranosides 13 and 14 displayed a maximum with respect to chain length, i.e., the hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon C14 to C17 glucopyranosides showed mild cytotoxicity, whereas the short (C7) and long-chain (C18 and C19) glucopyranosides, including octylthioglucoside as positive control, were less toxic, with most EC50 values > 250 μM. The EC50 values of the small number of maltopyranosides 17 and 18 investigated suggest that the cytotoxicity of this class of carbohydrate surfactants may also display a maximum in EC50 values with respect to chain length. Although similar trends have been reported for the biological activity of many surface active compounds in non-mammalian model systems, especially for compounds with anaesthetic and antimicrobial activity [17], a “cut-off” effect in the biological activities has not been reported previously for carbohydrate surfactants in general and fluorinated carbohydrate surfactants in particular.

The existence of a “cut-off” effect is surprising because the membrane permeability of organic compounds is proportional to their hydrophobicity (e.g., assessed by the octanol-water partition coefficient or the hydrophile-lipophile balance). Assuming that the biological activity (e.g., cytotoxicity) correlates with the membrane permeability (and, thus, the cellular uptake), the toxicity of the surfactants is expected to increase (and not to decrease) with increasing length of the hydrophobic tail. The low toxicity of C7 surfactants and the moderate toxicity of C14 to C17 surfactants are consistent with this expectation. However, the low toxicity of most C18 and C19 surfactants and the galactopyranosides 15 and 16 suggests that the membrane permeability is not the only determinant of the cytotoxicity, especially after a comparatively long exposure of 24 h. Several other factors, such as decreasing aqueous and lipid solubility, decreasing critical micelle concentration (as measure of hydrophobicity and detergency), increasing binding to proteins in the cell culture medium (e.g., albumin) or decreasing diffusion through the cell membrane with increasing tail length and increasing degree of fluorination, are likely to play a role [17, 30]. Independent of the factors ultimately contributing to the low toxicity of the long-chain surfactants in cells in culture, our results suggest that the length and the degree of fluorination of the hydrophobic tail are important determinants of their toxicity.

Another intriguing observation is the low toxicity of the galactopyranoside surfactants 15 and 16 compared to the corresponding glucopyranoside surfactants 13 and 14. Similarly, Kasuya and co-workers reported that 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,9,9,10,10,11,11,12,12,12-heneicosafluoro-dodecyl-β-D-glucopyranoside was nontoxic in the B16 melanoma cell line at a concentration of 50 μM (48 h exposure), whereas the corresponding β-D-galactopyranoside displayed some toxicity at the same concentration [14]. These findings show that not only the length of the hydrophobic tail and the degree of fluorination [10-15], but also the stereochemistry of the polar headgroup are important determinants of the cytotoxicity of carbohydrate surfactants. Specifically, the absolute configuration of the hydroxyl group at the C-4 position determines the cytotoxicity of gluco- versus galactopyranoside surfactants in the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line.

Since analogous gluco- and galactopyranoside surfactants have a comparable headgroup size, the differences in the EC50 values between these two surfactant groups suggest selective mechanism(s) of toxicity. In agreement with this interpretation, the low toxicity of all surfactants suggests that their cytotoxic effect is not due to the massive disruption of the phospholipid membrane. Instead, it is more likely that the cytotoxic effect is a result of more or less selective interactions of the surfactants with lipid rafts. These interactions impair the function of membrane proteins, which results in the activation of pathways inducing apoptosis and/or necrosis. This hypothesis is supported by our earlier study showing that the glucopyranosides β-13e and β-14e induced apoptosis in B16F10 cells [15]. Similarly, other surfactants have been shown to cause a ligand-independent clustering of death receptors, such as Fas, in membrane rafts, which provides scaffolds for the coupling of adaptor and effector proteins involved in apoptosis [31]. The selectivity of these complex surfactant-lipid and surfactant-protein interactions is affected both by the structure of the hydrophobic tail and the structure and stereochemistry of the polar headgroup.

4.2. Haemolytic activity

At haemolytic concentrations, surfactants directly destabilize the cell membrane and alter the anchoring of the cytoskeleton complex to the cell membrane, followed by massive release of the cell content [8, 9, 32]. Therefore, it is not surprising that, in comparison to the cytotoxic effect, much higher concentrations of the surfactants (>3.3 mM; Table 1) were typically needed to induce haemolysis. Furthermore, serum was protective against haemolysis due to binding of the surfactants to albumin, which lowers the free concentration of the surfactants and minimizes its partitioning into the cell membrane. The only exception was the C16 maltopyranoside surfactant β-17b, which was the most haemolytic compound under investigation. Similarly, the corresponding C12 maltopyranoside has been reported to be a potent haemolytic agent and causes lysis of human erythrocytes at concentrations as low as 58 μM [9].

Some limited structure-activity relationships have been reported for the haemolytic activity of carbohydrate surfactants. Their haemolytic activity depends on the headgroup, the length of the hydrophobic tail and the degree of fluorination. For example, the haemolytic activity of short-chain surfactants (C8 to C12) decreases with decreasing size of the carbohydrate headgroup (disaccharide > monosaccharide headgroup) and flexibility of the headgroup (pyranoside > straight polyhydroxylated chain), but increases with increasing tail length [1, 33]. In contrast, a fluorinated tail protects against haemolysis, with high micromolar or low millimolar concentrations typically displaying no haemolytic activity [10, 12, 34]. In agreement with these earlier studies, maltopyranosides displayed more haemolytic activity compared to gluco- and galactopyranosides and a fluorinated tail protected against haemolysis by β-glucopyranosides and maltopyranosides. In conclusion, the haemolytic activity of the surfactants investigated herein is not a concern for in vivo applications because of the high concentrations (> 3.3 mM) needed to induce haemolysis in vitro and the strong protective effect of serum.

4.3. Membrane partition behaviour

Our studies of the cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity suggest that carbohydrate surfactants with short (C7) hydrophobic tail are less toxic and display comparatively low haemolytic activity compared to surfactants with C14 to C17 tails (Table 1). For example, the short-tail surfactant β-13a was not toxic in cells in culture (EC50 > 250 μM) and not haemolytic (EC50 > 3.3 mM) in the concentration range investigated in this study, whereas long-chain surfactant β-13d was both toxic and haemolytic in the same concentration range. In contrast, all short-chain and most long-chain galactopyranosides, such as β-15b, displayed no cytotoxicity and little-to-no haemolytic activity in the concentration range studied. One possible explanation for the low cytotoxicity and low haemolytic activity of, for example, β-13d and β-15b is a poor tendency of both compounds to partition into cell membranes. To test this hypothesis, we studied the effect of three hydrocarbon surfactants, β-13a, β-13d and β-15b, on dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) bilayers using fluorescence anisotropy measurements. DPPC bilayers were selected because they are frequently used to study the membrane partition behaviour of organic compounds [35].

The changes in the phase behaviour of the DPPC model membranes were characteristic for the incorporation of many small molecules into phospholipid bilayers and indicated a loss of cooperativity in the bilayer at micromolar concentrations. Specifically, Tm decreased and the transition width increased with increasing concentrations of all three carbohydrate surfactants. A similar effect of a C12 glucopyranoside and several other short chain carbohydrate surfactants on DPPC model membranes has been reported previously [16]. However, there were distinct differences in the effect of β-13d versus β-15b on Tm, which supports the above mentioned hypothesis that carbohydrate surfactants can interact selectively with lipid rafts in (model-)cell membranes, thus inducing a toxic effect at different concentrations and by different modes of action. Furthermore, the apparent membrane partition coefficients increased in the order heptyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13a) ≪ hexadecyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-13d) ~ hexadecyl β-D-galactopyranoside (β-15b). The smaller membrane partition coefficient of β-13a and its minimal influence on the phase transition behaviour of DPPC bilayers indicate that short-chain (C7) carbohydrate surfactants have only a small tendency to partition into cell membranes. The partition coefficients of the long-chain surfactants β-13d and β-15b were higher compared to β-13a, which is in agreement with other studies reporting an increasing tendency of surface active compounds to partition into (model) membranes [30]. Interestingly, the partition coefficients of β-13d and β-15b were of the same order of magnitude. Together these observations suggest that the low toxicity of the C7 surfactants is a result of the small partition coefficient of these surfactants, independent of the headgroup. In contrast, the low toxicity of galactopyranosides 14 and 15 is not correlated with simple physicochemical properties, such as the membrane partition coefficient. Instead, differences in the three-dimensional structure of the headgroup (i.e., galactose versus glucose) and, possibly, the interaction of β-15b (and other long-chain galactopyranosides) with phospholipids molecules in a (model) membrane play, as suggested above, a role in the toxicity of these two surfactant groups. The later hypothesis is supported by the different trend in the depression of Tm of β-15b versus β-13d (Figure 4).

5. Conclusions

The chain length, the degree of fluorination and the headgroup structure are important determinants of the cytotoxicity and the haemolytic activity of nonionic carbohydrate surfactants. Of particular interest is the “cut-off” effect observed in the initial biocompatibility assessment of the hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon glucopyranoside surfactants (i.e., the cytotoxicity of these carbohydrate surfactants displayed a maximum at hydrophobic tail length ranging from C14 to C17). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that such a “cut-off” effect has been reported in a mammalian cell culture system for carbohydrate surfactants in general and fluorinated surfactants in particular. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of surfactants with glucose versus galactose headgroups depended on the stereochemistry in the C-4 position of the pyranoside. Studies of the surfactant-lipid interactions suggest that short chain surfactants are a lower tendency to partition into lipid membranes, which may explain their lower toxicity compared to C14 to C17 surfactants. C16 surfactants with glucose and galactose headgroups appear to have comparable membrane partition coefficients, but affect membrane phase behaviour (i.e., Tm) differently at surfactant concentrations > 10 μM. The later finding clearly indicates that the cytotoxicity of the carbohydrate surfactants is due to highly specific surfactant-lipid interactions. This interpretation of our results is further supported by the fact that haemolysis of red blood cells occurs at much higher concentrations. Overall, these finding suggest that membrane partition behaviour and specific surfactant-lipid interactions are important determinants of the biocompatibility of simple carbohydrate-based surfactants investigated for a range of pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES12475), the National Science Foundation (NIRT 0210517), the U.S. Department of Agriculture Biomass Research and Development Initiative (Grant Agreement 68-3A75-7-608) and the Department of Energy Development and Independence, Energy and Environment Cabinet of The Commonwealth of Kentucky. Additional support was provided by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic (grant No. MZE-0002716201) and NAZV QF-3115 to JT. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Söderlind E, Wollbratt M, von Corswant C. The usefulness of sugar surfactants as solubilizing agents in parenteral formulations. Int J Pharm. 2003;252:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Söderlind E, Karlsson L. Haemolytic activity of maltopyranoside surfactants. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;62:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riess JG, Krafft MP. Fluorocarbons and fluorosurfactants for in vivo oxygen transport (blood substitutes), imaging, and drug delivery. MRS Bull. 1999;24:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehmler H-J. Perfluorocarbon compounds as vehicles for pulmonary drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:247–262. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmler H-J, Bummer PM, Jay M. Liquid ventilation - a new way to deliver drugs to diseased lungs? CHEMTECH. 1999;29:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaffer TH, Wolfson MR, Clark LC. Liquid ventilation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1992;14:102–109. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950140208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Liquid ventilation: An adjunct for respiratory management. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:15–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isomaa B, Haegerstrand H, Paatero G, Engblom AC. Permeability alterations and antihemolysis induced by amphiphiles in human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;860:510–524. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isomaa B, Haegerstrand H, Paatero G. Shape transformations induced by amphiphiles in erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;899:93–103. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milius A, Greiner J, Riess JG. Synthesis of f-alkylated glycosides as surfactants for in vivo uses. Effects of the length of the hydrocarbonated spacer in the aglycone on königs-knorr reaction, surface activity and biological properties. New J Chem. 1991;15:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarif L, Greiner J, Riess JG. Perfluoroalkylated monoesters of 1,4-d-sorbitan, isosorbide, and isomannide: New surfactants for biomedical applications. J Fluorine Chem. 1989;44:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarif L, Greiner J, Pace S, Riess JG. Synthesis of perfluoroalkylated xylitol ethers and esters: New surfactants for biomedical uses. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1262–1269. doi: 10.1021/jm00166a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasuya MCZ, Cusi R, Ishihara O, Miyagawa A, Hashimoto K, Sato T, Hatanaka K. Fluorous-tagged compound: A viable scaffold to prime oligosaccharide synthesis by cellular enzymes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasuya MCZ, Ito A, Cusi R, Sato T, Hatanaka K. Cellular uptake and saccharide chain elongation of “fluoro-amphiphilic” glycosides. Chem Lett. 2005;34:856–857. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Turánek J, Knötigová P, Kudlácková H, Mašek J, Pennington DB, Rankin SE, Knutson BL, Lehmler H-J. Synthesis and biocompatibility evaluation of fluorinated, single-tailed glucopyranoside surfactants. New J Chem. 2008;32:2169–2179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozycka-Roszak B, Jurczak B, Wilk KA. Effects of nonionic sugar surfactants on the phase transition of dppc membranes. Thermochim Acta. 2007;453:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balgavy P, Devinsky F. Cut-off effects in biological activities of surfactants. Adv Colloid Interf Sci. 1996;66:23–63. doi: 10.1016/0001-8686(96)00295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turanek J, Kasna A, Zaluska D, Neca J, Kvardova V, Knotigova P, Horvath V, Sindlerova L, Kozubik A, Sova P, Kroutil A, Zak F, Mistr A. New platinum(iv) complex with adamantylamine ligand as a promising anti-cancer drug: Comparison of in vitro cytotoxic potential towards a2780/cisr cisplatin-resistant cell line within homologous series of platinum(iv) complexes. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2004;15:537–543. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000127147.57796.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vyas SM, Turanek J, Knoetigova P, Kasna A, Kvardova V, Koganti V, Rankin SE, Knutson BL, Lehmler H-J. Synthesis and biocompatibility evaluation of partially fluorinated pyridinium bromides. New J Chem. 2006;30:944–951. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bank U, Reinhold D, Ansorge S. Measurement of cellular activity by means of the mtt color test. Optimization of the method. Allerg Immunol. 1991;37:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie W, Kania-Korwel I, Bummer PM, Lehmler H-J. Effect of potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorooctanoate and octanesulfonate on the phase transition of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (dppc) bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue T, Iwanaga T, Fukushima K, Shimozawa R. Effect of sodium octanoate and sodium perfluorooctanoate on gel-to-liquid-crystalline phase transition of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine vesicle membrane. Chem Phys Lipids. 1988;46:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(88)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biltonen RL, Lichtenberg D. The use of differential scanning calorimetry as a tool to characterize liposome preparations. Chem Phys Lipids. 1993;64:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrovic Z, Konstantinovic S, Spasojevic A. Bf3 etherate-induced formation of c7-c16-alkyl β-d-glucopyranosides. Indian J Chem. 2004;43B:132–134. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladmiral V, Mantovani G, C GJ, Cauet S, Irwin JL, Haddleton DM. Synthesis of neoglycopolymers by a combination of “click chemistry” and living radical polymerization. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4823–4830. doi: 10.1021/ja058364k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milkereit G, Morr M, Thiem J, Vill V. Thermotropic and lyotropic properties of long chain alkyl glycopyranosides part iii: Ph-sensitive headgroups. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;127:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vill V, von Minden HM, Koch MHJ, Seydel U, Brandenburg K. Thermotropic and lyotropic properties of long chain alkyl glycopyranosides. Part i: Monosaccharide headgroups. Chem Phys Lipids. 2000;104:75–91. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Springer Science + Business Media; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamp F, Hamilton JA. How fatty acids of different chain length enter and leave cells by free diffusion. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. Fas/cd95 death receptor and lipid rafts: New targets for apoptosis-directed cancer therapy. Drug Resistance Updates. 2006;9:51–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haegerstrand H, Isomaa B. Morphological characterization of exovesicles and endovesicles released from human erythrocytes following treatment with amphiphiles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1109:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90074-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soederlind E, Karlsson L. Haemolytic activity of maltopyranoside surfactants. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;62:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abouhilale S, Greiner J, Riess JG. Perfluoroalkylated fatty acid monoesters of trehalose and sucrose for biomedical applications: Remarkable emulsifying properties of 6-0-[3’-(perfluorooctyl)propanoyl]trehalose. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1992;69:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohner K. Effects of small organic molecules on phospholipid phase transitions. Chem Phys Lipids. 1991;57:341–362. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(91)90085-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.