Abstract

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) causes secondary brain injury due to vasospasm and inflammation. Here, we studied a rat model of mild-to-moderate SAH intended to minimize ischemia/hypoxia to examine the role of sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) in the inflammatory response induced by SAH. mRNA for Abcc8, which encodes SUR1, and SUR1 protein were abundantly upregulated in cortex adjacent to SAH, where tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and nuclear factor (NF)κB signaling were prominent. In vitro experiments confirmed that Abcc8 transcription is stimulated by TNFα. To investigate the functional consequences of SUR1 expression after SAH, we studied the effect of the potent, selective SUR1 inhibitor, glibenclamide. We examined barrier permeability (immunoglobulin G, IgG extravasation), and its correlate, the localization of the tight junction protein, zona occludens 1 (ZO-1). SAH caused a large increase in barrier permeability and disrupted the normal junctional localization of ZO-1, with glibenclamide significantly reducing both effects. In addition, SAH caused large increases in markers of inflammation, including TNFα and NFκB, and markers of cell injury or cell death, including IgG endocytosis and caspase-3 activation, with glibenclamide significantly reducing these effects. We conclude that block of SUR1 by glibenclamide may ameliorate several pathologic effects associated with inflammation that lead to cortical dysfunction after SAH.

Keywords: caspase-3, inflammation, subarachnoid hemorrhage, sulfonylurea receptor 1, vasogenic edema, zona occludens 1

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is an important contributor to the overall stroke burden in society (Suarez et al, 2006). Among those who survive SAH, secondary brain injury leads to significant early and delayed morbidity, including long-term cognitive and psychosocial disability, which are encountered in up to 50% of patients who make an otherwise good recovery in terms of self-care (Hackett and Anderson, 2000; Mayer et al, 2002).

Ischemic/hypoxic injury due to cerebral vasospasm is considered to be a major cause of secondary injury to the brain after SAH. However, there is growing recognition that vasospasm alone does not fully account for the morbidity observed after SAH (Hansen-Schwartz et al, 2007; Macdonald et al, 2007). Recent studies indicate that reversing vasoconstriction, for example with the endothelin antagonist, clazosentan, is not necessarily associated with improved clinical outcome (Macdonald et al, 2008).

Additional mechanisms of secondary injury besides vasospasm have been identified after SAH (Hansen-Schwartz, 2004; Cahill et al, 2006; Macdonald et al, 2007). Arguably the most important involves inflammation, which invariably is associated with secondary injury to the brain and which may itself be responsible for vasospasm (Sercombe et al, 2002). Hallmarks of an inflammatory response in the cortex include vasogenic edema due to altered barrier permeability, and cell loss due to apoptosis (Stanimirovic and Satoh, 2000; Petty and Lo, 2002; Stamatovic et al, 2006). However, molecular mechanisms linking inflammation to barrier permeability and apoptosis in SAH have not been elucidated.

The sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1)-regulated NCCa-ATP channel has been implicated in brain edema and cell death in the context of ischemia/hypoxia (Simard et al, 2006, 2007a, 2008b), but a similar role in inflammation has not previously been postulated. However, when we analyzed the promoter region of Abcc8, the gene that encodes SUR1, we discovered that in rat and human, the 5′-flanking region contains at least two consensus binding sites for nuclear factor κB(NFκB). This finding suggested that SUR1 might be transcriptionally upregulated in the context of inflammation, and might participate in the pathologic response to SAH and other inflammatory conditions that affect the central nervous system.

Here, we used a rat model of mild-to-moderate SAH to test the hypothesis that SUR1 is an important element in the inflammatory response after SAH. We report that SUR1 is upregulated after SAH, and that block of SUR1 using glibenclamide abrogates several pathologic manifestations of SAH, including inflammation, vasogenic edema, and caspase-3 activation. Our findings provide novel insights into molecular mechanisms responsible for cortical dysfunction after SAH, and point to SUR1 as a potential therapeutic target in SAH.

Methods

Model of SAH

All surgical procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland. An investigator who was blinded to the treatment and who did not evaluate outcome performed all of the surgical procedures. Fasted male Wistar rats (225 to 275 gm; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were anesthetized (ketamine, 60 mg/kg and xylazine, 7.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and allowed to ventilate air spontaneously. Temperature was maintained at 371C using a heating pad regulated by a rectal temperature sensor (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) probe (MoorLab, Moore Instruments, Sussex, UK) was affixed to the skull. The right carotid sheath was exposed through a ventral midline incision, the common, external and internal carotid arteries (CCA, ECA, ICA) were dissected, and the pterygopalatine artery was ligated. Typical blood gases (i-STAT; Heska Corp, Fort Collins, CO, USA), sampled from the CCA before injury, were pO2 > 90 mm Hg, pCO2 < 47 mm Hg, and glucose 150 to 200 mg/dL.

The model of SAH involved a single endovascular puncture of the ICA using a 4−0 filament sharpened at its tip, followed by reperfusion of the ICA (Schwartz et al, 2000). With temporary clips on the CCA and ICA, the ECA was divided proximal to the ligature, the 4−0 nylon filament was introduced through the stump of the ECA into the ICA, arterial puncture was produced at ∼19 mm under LDF monitoring, the filament was withdrawn, the ECA stump was ligated and flow was restored to the CCA/ICA. Unlike the widely used method in which a 3−0 filament is used to produce severe hemorrhage associated with high mortality, the method used here utilizing a 4−0 filament produced mild-to-moderate SAH associated with low mortality. We monitored relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) using LDF to confirm the sharp decrease after puncture and filament withdrawal, and to assure the full recovery in rCBF within 10 to 15 mins of restoration of flow in the ICA, making ischemic injury less likely than in versions of the model in which the CCA is ligated. For the study reported here, 49 rats were subjected to the procedure for SAH, and of these, 5 rats were excluded due to subdural hemorrhage (attributed to proximal puncture), 6 did not exhibit adequate reperfusion, and 3 died early of unknown causes, leaving 35 for study.

To evaluate ischemic tissue injury 24 h after SAH, 2-mm coronal sections of brain were immersed in 2% 2,3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in NS for 20 mins at 37°C. To evaluate tissue hypoxia (pO2 < 10 mm Hg) 24 h after SAH, rats were administered pimonidazole HCl (60 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) 30 mins before killing, and sections were immunolabeled according to the manufacturer's protocol (Hypoxyprobe-1 Plus kit; NPI, Burlington, MA, USA).

To evaluate the role of SUR1 in SAH, we examined the effect of the potent, selective SUR1 blocker, glibenclamide, administered at a low dose that does not produce hypoglycemia (Simard et al, 2008a, b). Shortly after (< 15 mins) inducing SAH, a loading dose of glibenclamide was administered (10 μg/kg, intraperitoneally) and a miniosmotic pump (Alzet 2002, 0.5 μL/h; Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA) was implanted for continuous infusion of drug subcutaneously. Controls received the same volume of vehicle in the same way. A stock solution of glibenclamide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was made by placing 50 mg into 10 mL dimethylsulphoxide, and the injection/infusion solution was made by placing 400 μL stock into 4.6 mL unbuffered saline (0.9% NaCl) and clarifying the solution using a few microliters of 0.1 N NaOH (final pH ∼8.5). The osmotic mini-pumps delivered 0.5 μL/h, yielding infusion doses of 200 ng/h. This treatment is estimated to yield serum concentration < 10 nmol/L and has minimal effects on serum glucose (Simard et al, 2008a, b).

Rats were killed 24 h after induction of SAH. In some cases, fresh tissues were collected for immunoblot. In other cases, animals underwent perfusion fixation for immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryosections (10 μm) were postfixed with 4% formaldehyde and immunolabeled using standard techniques. After permeabilizing (0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 mins), sections were blocked (2% donkey serum for 1 h; Sigma; D-9663), then incubated with primary antibody directed against: SUR1 (1:200; SC-5789; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); NeuN (1:100; MAB377; Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA); glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:500; CY3 conjugated; C-9205; Sigma); vonWillebrand factor (1:200; F3520; Sigma); tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); p65 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); FITC-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); zona occludens 1 (ZO-1; 1:100; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA). Fluorescent-labeled, species appropriate secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used for visualization. Omission of primary antibody and competition with antigenic peptides, when available, were used as negative controls. Fluorescent signals were visualized using epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E1000).

For quantitative immunohistochemistry, all sections were immunolabeled as a single batch, as previously described (Gerzanich et al, 2003). All images were collected using uniform parameters of magnification and exposure. Segmentation analysis was performed by computing a histogram of the pixel intensity for equal regions of interest (ROI) using IP Lab software, with the ROI confined to the 400 μm of parenchymal tissue dorsal to the pia of the inferomedial cortex ipsilateral to the SAH. For IgG, the overall pixel intensity of the ROI was determined and the background was subtracted. For TNFα, p65, and GFAP, specific labeling was defined as pixels with signal intensity greater than twice that of background, and the area occupied by pixels with specific labeling was used to determine the percent area with specific labeling (% ROI). For caspase-3, the number of nuclei with specific labeling in the ROI was counted.

Immunoblot

Lysates of inferomedial cortex, or of cultured bEnd.3 cells (ATCC, Monassas, VA, USA) that had been exposed to TNFα (20 ng/mL) for 6 h, were prepared by homogenizing in Radio-immuno-precipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer. SUR1 was immunoisolated using a custom antibody raised against amino acids 598 to 965 (Protein Id, NP_037171) in rabbits by a commercial service (Covance, Denver, PA, USA). This custom antibody was used to immunoisolate SUR1 using standard techniques, after which immunoisolated SUR1 was run on electrophoretic gels (NuPAGE 4% to 12% Bis–Tris gels; Novex; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). SUR1 was detected using the same custom antibody. Membranes were stripped and reblotted for β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma), which was used as a loading control. Detection was performed using the ECL system (Amersham BioTBIences Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA) with routine imaging (Fuji LAS-3000) and quantification (Scion Image; Scion Corp, Frederick, MD, USA).

In Situ Hybridization

Fresh-frozen sections were postfixed in 5% formaldehyde for 5 mins. Digoxigenin-labeled probes (sense: 5′-GCCCGGGCACCCTGCTGGCTCTGTGTGTCCTTCCGCGCCTGGGCATCG-3′) were designed and supplied by GeneDetect and hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (www.genedetect.com/protocols.htm).

RT-PCR

bEnd.3 cells were exposed to TNFα (20 ng/mL) for 6 h. RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed using Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The target transcript was reverse transcribed at RT for 10 mins, then incubated at 42°C for 15 mins. The cDNA was amplified using 35 cycles under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 secs; 57°C for 45 secs; 72°C for 45 secs. The oligonucleotide primers corresponding to SUR1 were as follows: SUR1 (accession number NM_011510), forward primer (base 2,630 to 2,649) ccctctaccagcacaccaat, reverse primer (base 3,059 to 3,078) ctgatgcagcaccgaagata. RT-PCR products (449 bp) were analyzed using 2.0% agarose/EtBr gel electrophoresis.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

TNFα-stimulated activity of the promoter region of Abcc8 was determined using luciferase reporter plasmids as previously described. HeLa cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing the rAbcc8 promoter (−3,853 to + 125) or four tandem NFκB consensus sequences (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA, USA) using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). Co-transfection of pRL-CMV, Renilla luciferase expression plasmid served as a control for transfection efficiency. The luciferase activity of cell extracts was determined using the Dual Luciferase system from Promega.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared from bEnd.3 cells exposed to TNFα (20 ng/mL) using the N-XTRACT CelLytic NuCLEAR Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed with biotinylated 22-bp duplex (5′-biotin-ACTTGGGAAATTCCCAAGCACC-3′; Invitrogen) encompassing the binding site of NFκB on the proximal promoter region of rAbcc8. Biotinylated oligonucleotides were annealed as recommended by the manufacturer and mixed with the nuclear extract as per the protocol outlined in LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (20148; Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). This mixture was run on a DNA Retardation Gel (Invitrogen) and transferred onto Biodyne B Pre-Cut Nylon Membrane (Pierce Biotechnology). Imaging was performed as for immunoblots. Specific binding to the target sequence was verified by competition with a 200-fold excess of unlabeled probe.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t-test or analysis of variance was used for group comparisons, as appropriate. A difference between groups was deemed to be significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Filament Puncture of ICA Produces Inflammation but not Hypoxia

To permit study of the inflammatory response to SAH exclusive of complications due to ischemia/hypoxia, we used a rat model of mild-to-moderate SAH (Schwartz et al, 2000). In this model, SAH is produced by puncture of the ICA using an intraluminal 4−0 filament, with restoration of flow in the ICA. Blood accumulates in the subarachnoid space overlying the inferomedial cortex and in the basal cistern that contains the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) (Figure 1A). A single puncture with a 4−0 filament yields mild-to-moderate SAH, which is associated with low mortality, no delayed vasospasm, and no gross neurobehavioral abnormalities (Schwartz et al, 2000).

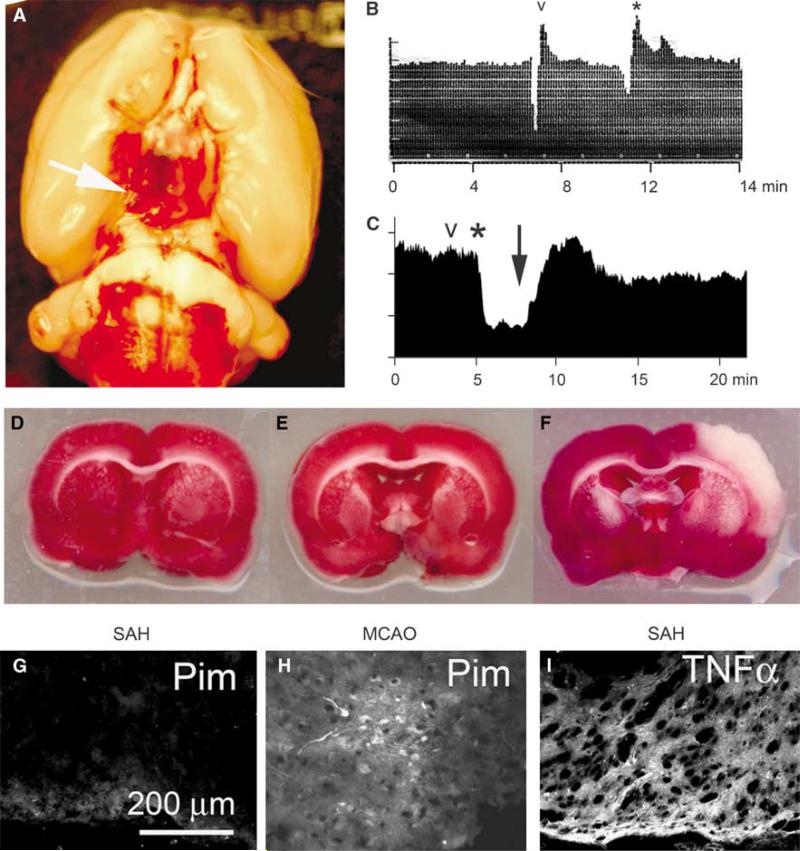

Figure 1.

Filament puncture of ICA produces mild-to-moderate subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and inflammation but not ischemia/hypoxia. (A) Photograph of the base of the brain showing SAH overlying the inferomedial cortex and bathing the posterior cerebral artery (arrow) in the basal cistern. (B, C) Laser-Doppler flowmetry of the ipsilateral MCA territory showing changes in relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) associated with filament positioning (B) and with artery penetration (C; same rat as in A); ‘v’, time of positioning/puncture; *, time of withdrawal of filament; ↓, time of restoration of flow in ICA. (D–F) 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)-stained coronal sections from rats with filament positioning without puncture (D), with puncture resulting in SAH (E), and with deliberate MCA occlusion lasting 2 h (F). (G, H) Inferomedial cortex from a rat with SAH induced 24 h earlier (G) and region of infarct in a rat with 2-h middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), used as a positive control; both rats were administered pimonidazole and sections were immunolabeled with antibody against pimonidazole to identify tissues with pO2 < 10 mm Hg. (I) Inferomedial cortex from a rat with SAH induced 24 h earlier, immunolabeled for TNFα to show inflammatory response. The results shown are representative of findings in three or more experiments.

We tested whether this model of mild-to-moderate SAH was associated with ischemia/hypoxia. Positioning the filament without puncturing the artery (‘sham’) was sometimes associated with a momentary reduction in rCBF that was of no hemodynamic significance (Figure 1B). After actual puncture, withdrawal of the filament resulted in a decrease in rCBF to 50% to 70% of baseline, which normalized gradually within 10 to 15 mins upon restoration of flow in the ICA (Figure 1C). None of these changes in rCBF produced ischemic effects measurable by staining with TTC (Figures 1D and 1E). Intentional occlusion of the MCA for 2 h causes a reliable infarction in dorsolateral cortex (Simard et al, 2008b), but not in the inferomedial cortex where blood accumulates after SAH (Figure 1F).

The presence of minimal hypoxia in the inferomedial cortex was confirmed using pimonidazole, which labels tissues where pO2 < 10 mm Hg (Figure 1G versus Figure 1H). By contrast, immunolabeling for the proinflammatory cytokine, TNFα, showed significant upregulation in the inferomedial cortex underlying the subarachnoid blood (Figure 1I). In combination, these data point to inflammation as the dominant mechanism underlying pathologic changes in this model of mild-to-moderate SAH.

SUR1 is Upregulated After SAH

Previous studies have shown that SUR1 and functional SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels are upregulated in various forms of severe central nervous system injury (Simard et al, 2006, 2007b, 2008a), but this has not been reported in a nonhypoxic, proinflammatory context such as mild-to-moderate SAH.

In situ hybridization was used to detect mRNA for Abcc8, which encodes SUR1. In uninjured controls, the inferomedial cortex showed no signal (Figure 2A), but 24 h after SAH, strong expression of Abcc8 mRNA was evident in neurons and microvessels in the inferomedial cortex adjacent to the SAH (Figures 2B and 2C). Immunohistochemistry for SUR1 showed minimal labeling in uninjured controls (Figure 2D), but 24 h after SAH, abundant expression of SUR1 was evident in the inferomedial cortex (Figure 2E). SUR1 upregulation in the inferomedial cortex 24 h after SAH was confirmed by immunoblot (Figure 2F). SUR1 expression was especially prominent in capillaries that colabeled for vonWillebrand factor (Figures 3A–3C), and in neurons that colabeled with NeuN (Figures 3D–3F).

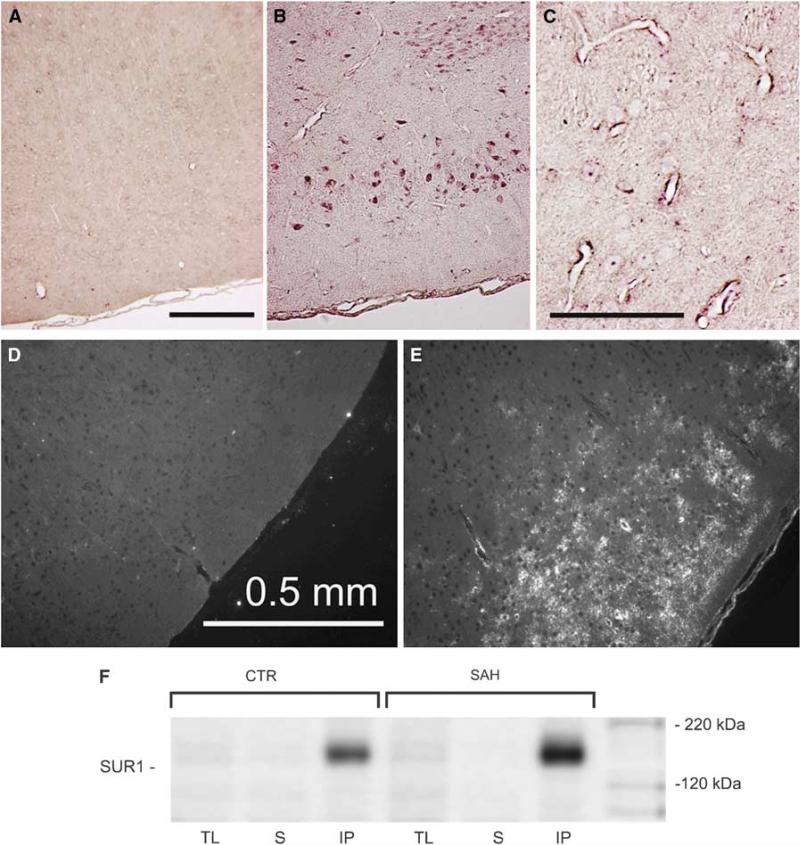

Figure 2.

Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein are upregulated in cortex adjacent to SAH. (A–C) In situ hybridization for Abcc8 in inferomedial cortex from an uninjured control rat (A) and from a rat 24 h after SAH (B, C); bars, 200 μm. (D, E) Low power views of inferomedial cortex immunolabeled for SUR1 in an uninjured control rat (D) and in a rat 24 h after SAH (E). (F) Immunoblots of SUR1 immunoisolated from the inferomedial cortex from an uninjured control rat (CTR) and from a rat 24 h after SAH; immunoblots are shown for total lysates (TL), for supernatant after immunoprecipitation (S) and for immunoprecipitated SUR1 (IP). Immunolabeling was performed using a commercial anti-SUR1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); immunoisolation and immunoblotting were performed using the custom anti-SUR1 antibody described in ‘Materials and methods’. The results shown are representative of findings in three or more experiments.

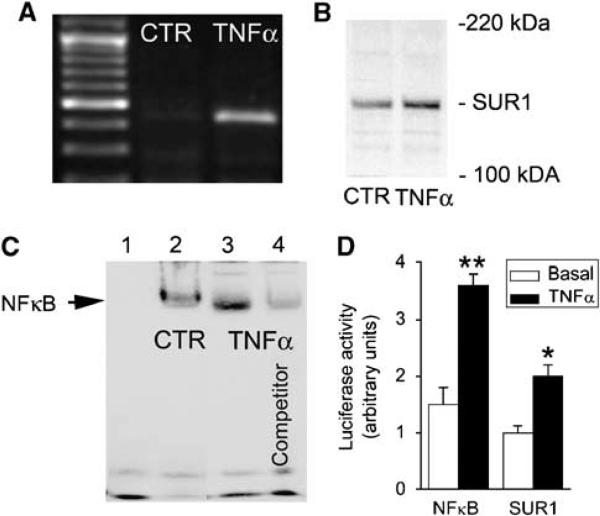

Figure 3.

SUR1 is upregulated in neurons and endothelial cells after SAH. (A–F) High power views of the inferomedial cortex immunolabeled for SUR1 (A, D) and colabeled for von Willebrand factor (B) or NeuN (E) in a rat 24 h after SAH; merged images are also shown (C, F). (G–L) Cross-sections of the posterior cerebral artery immunolabeled for SUR1 (G, J) and colabeled for von Willebrand factor (H, K) in an uninjured control rat (G–I) and in a rat 24 h after SAH (J–L); merged images are also shown (I, L). The results shown are representative of findings in five experiments.

We also examined SUR1 expression in the PCA, which was outside of the path of direct injury by filament puncture, but which was bathed in extravasated blood due to its location in the basal cistern. Immunohistochemistry showed minimal labeling for SUR1 in uninjured controls (Figures 3G–3I), but 24 h after SAH, abundant expression of SUR1 was evident in the PCA, especially in endothelium but also in smooth muscle and adventitial layers (Figures 3J–3L).

Abcc8 is Activated by TNα

We speculated that upregulation of Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein after SAH might be related to the proinflammatory environment associated with SAH. This conjecture was supported by analysis of the 5′-flanking region of the Abcc8 promoter from rat and human, which showed the presence of at least two consensus NFκB binding sites.

We tested whether TNFα, the canonical activator of NFκB, could activate Abcc8 in cultured brain endothelial (bEnd.3) cells. After a 6-h exposure to TNFα, Abcc8 mRNA (Figure 4A) and SUR1 protein (Figure 4B) were both increased, consistent with the hypothesis that TNFα/NFκB stimulates de novo expression of SUR1.

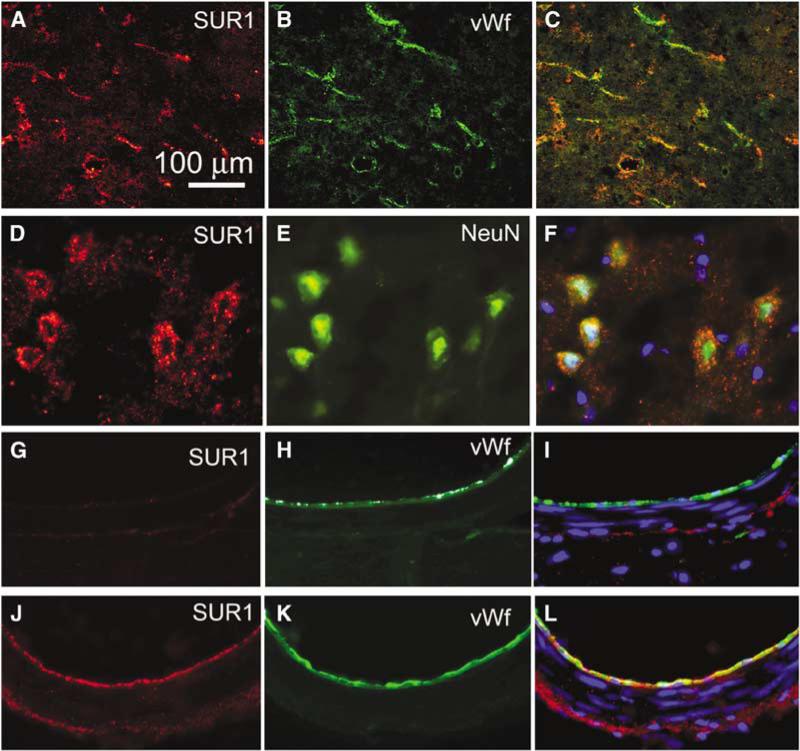

Figure 4.

Abcc8 is activated by TNFα in vitro. (A, B) RT-PCR (A) and immunoblot (B) showing mRNA for Abcc8 and SUR1 protein in bEnd.3 cells exposed to TNFα (20 ng/mL) for 6 h versus unstimulated cells (CTR). (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed using 22-bp DNA duplexes with a sequence encompassing the proximal NFκB consensus site on the rAbcc8 promoter (−357 to −348), plus: no nuclear extract (lane 1); nuclear extract from unstimulated bEnd.3 cells (CTR) (lane 2); nuclear extract from bEnd.3 cells stimulated with TNFα (20 ng/mL) (lane 3); same as lane 3 plus a 200-fold excess of unlabeled competitor duplex (lane 4). The results shown for RT-PCR, immunoblot, and EMSA are representative of findings in three to five replicate experiments. (D) Promoter activity was determined using a luciferase assay, in which the rAbcc8 promoter (−3,853 to + 125) or four tandem NFκB consensus sequences were linked to the luciferase gene; HeLa cells were transfected with these constructs, and luciferase activity, both basal and TNFα-stimulated (20 ng/mL), was quantified; n = 3 experiments; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Additional experiments were performed to advance this hypothesis. We used EMSA to test the hypothesis that NFκB can physically interact with the SUR1 promoter. EMSA was performed using nuclear lysate from cells exposed to TNFα, and with 22-bp DNA duplexes with a sequence encompassing the proximal NFκB consensus site on the Abcc8 promoter. Exposure of bEnd.3 cells to TNFα resulted in nuclear accumulation of the NFκB subunit, p65 (not shown). EMSA showed specific binding of nuclear extract to the DNA duplexes (Figure 4C), confirming that NFκB can physically interact with the rAbcc8 promoter.

Finally, we used a luciferase promoter assay to confirm the functionality of the putative NFκB binding sites in the Abcc8 promoter. Cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing the region of the rAbcc8 promoter encompassing the putative NFκB binding sites, or with plasmid containing four consensus NFκB binding sites, which was used as a positive control. Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of TNFα. As expected, TNFα stimulated luciferase activity driven by the NFκB binding sites ∼2.3-fold (Figure 4D). Similarly, activity of rAbcc8 promoter increased B2-fold with TNFα (Figure 4D), consistent with SUR1 transcription being stimulated by TNFα.

Together, the results from this series of experiments were consistent with the hypothesis that upregulation of Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein after SAH was related to the proinflammatory environment associated with SAH.

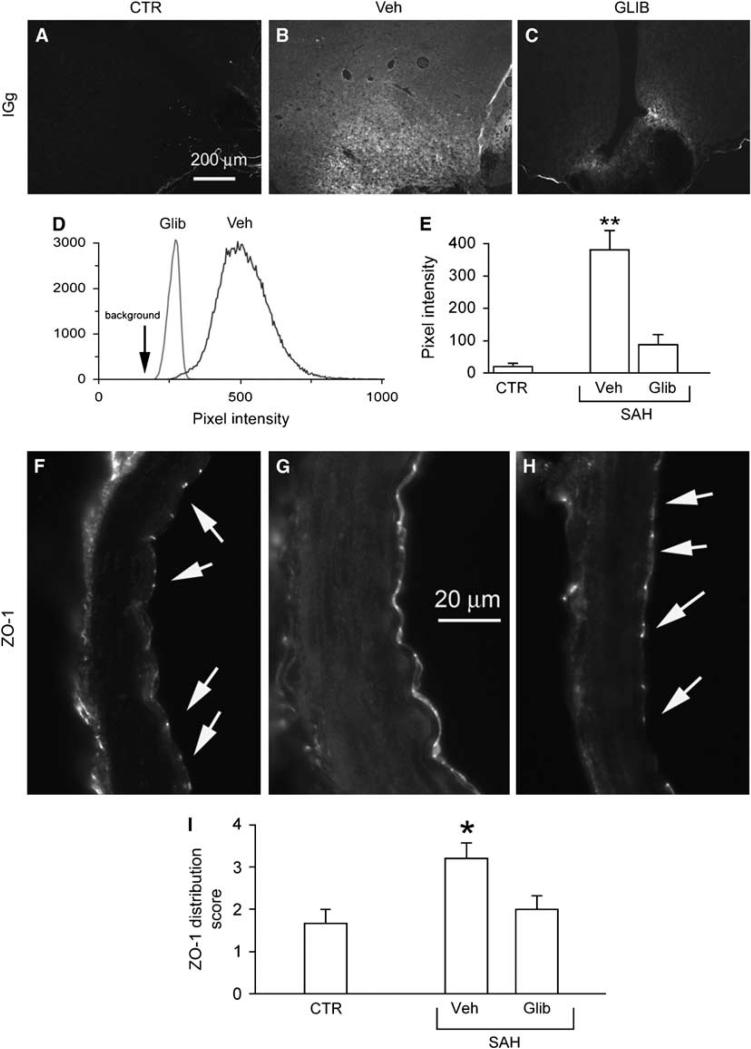

Barrier Permeability

A key pathologic manifestation of SAH (Scholler et al, 2007; Yan et al, 2008), as well as of TNFα upregulation (Megyeri et al, 1992; Holmin and Mathiesen, 2000), is an increase in barrier permeability, which leads to protein extravasation and formation of protein-rich vasogenic edema. We quantified protein extravasation in the inferomedial cortex 24 h after induction of SAH, using IgG as the representative protein because it is not synthesized in the brain and, with its large molecular mass, its extravasation reflects major barrier disruption. After SAH, IgG extravasation was especially prominent in the inferome-dial cortex adjacent to the blood (Figure 5B versus Figure 5A). By contrast, inhibiting SUR1 using low-dose glibenclamide after SAH resulted in a significant reduction in IgG extravasation (Figures 5C–5E), reflecting a significant attenuation in the SAH-induced alteration in barrier permeability.

Figure 5.

Glibenclamide reduces SAH-induced increase in barrier permeability and normalizes disruption of the tight junction protein, ZO-1. (A–C) Low power views of inferomedial cortex immunolabeled for rat IgG from an uninjured control rat (CTR) (A), and from rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (Veh) (B) or glibenclamide (GLIB) (C). (D, E) Quantitative analysis of IgG immunolabeling in two rats treated as indicated (D), and result of quantitative analysis in three groups of rats treated as indicated (E); five rats per group; **P < 0.01. (F–H) Cross-sections of PCA immunolabeled for ZO-1 from an uninjured control rat (F), and from rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (G) or glibenclamide (H). (I) Result of semiquantitative analysis of ZO-1 distribution in three groups of rats treated as indicated; scores of 1 to 4 represent, respectively: 1, punctate in most junctions; 2, punctate in all junctions; 3, predominantly junctional with some cytoplasmic localization; 4, predominantly cytoplasmic localization; 5 rats per group; *P < 0.05.

An increase in barrier permeability after SAH is associated with disruption interendothelial tight junctions (Yan et al, 2008). Although numerous proteins contribute to the integrity of tight junctions, ZO-1 is particularly important, because the proper cellular localization and sealing of tight junctions is believed to depend on its scaffolding properties and its interaction with the actin cytoskeleton (Lai et al, 2005; Fanning et al, 2007).

To gain insights into the link between endothelial SUR1 and barrier integrity, we examined endothelium of the PCA, which was bathed in subarachnoid blood and showed prominent upregulation of SUR1 (see above). The advantage of studying the PCA is that, unlike capillaries, a cross-section of its endothelial layer allows one to evaluate many interendothelial tight junctions at once, with immunohistochemical staining for tight junction proteins yielding a characteristic pattern of regularly spaced ‘points’ of labeling representing highly restricted junctional localization between adjacent endothelial cells.

In the absence of injury, the normal pattern of expression of ZO-1 was characterized by a highly restricted junctional localization, with no discernable cytoplasmic localization (Figure 5F). After SAH, in vehicle-treated rats, the pattern of ZO-1 expression was severely disrupted, shifting from the normal intercellular junctional localization to predominantly cytoplasmic localization (Figure 5G). This finding is consistent with previous observations in vitro, wherein TNFα was found to modulate tight junctions by rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton (Blum et al, 1997), and is consistent with the finding of IgG extravasation in the same rats. Notably, treatment with glibenclamide largely prevented the disorganization in the pattern of ZO-1 expression associated with SAH (Figure 5H)—glibenclamide significantly reduced cytoplasmic localization and restored intercellular localization (Figure 5I), correlating well with the significant reduction in altered barrier permeability.

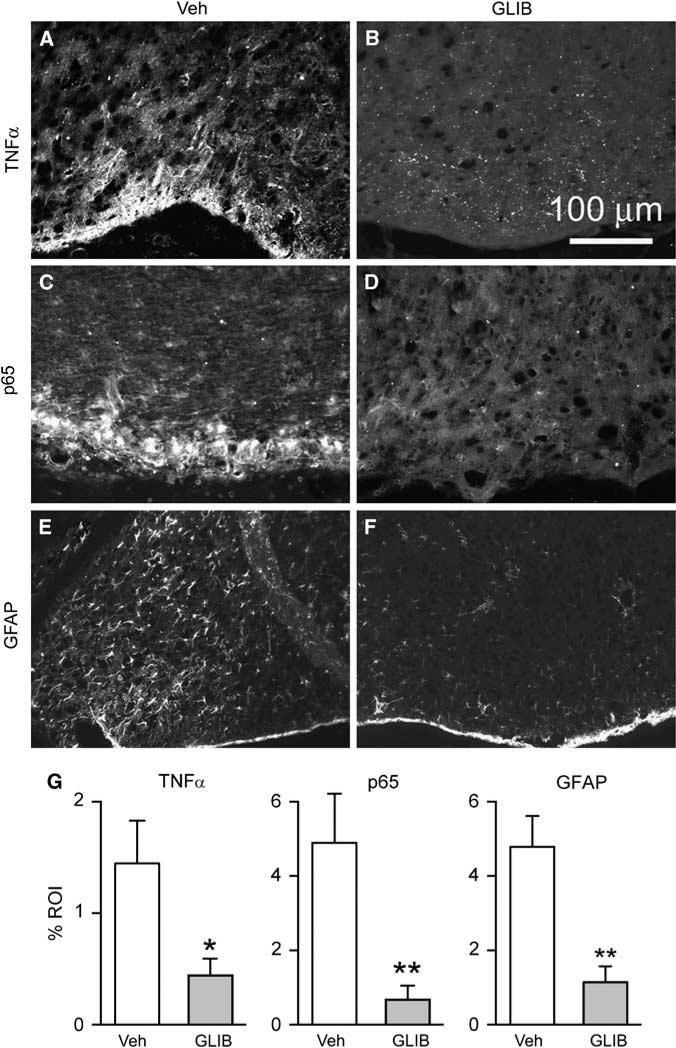

Inflammation

Protein extravasation (vasogenic edema) is associated with the accumulation of blood-borne substances in brain parenchyma that cause activation of microglia and astrocytes, and results in amplification of an inflammatory response (Yoshida et al, 2002; Wagner et al, 2005). We evaluated the local inflammatory response by immunolabeling for TNFα and NFκB (p65), and we evaluated reactive astrocytes using immunolabeling for GFAP. In rats administered vehicle after SAH, the local inflammatory response was robust and astrocytes were strongly activated (Figures 6A, 6C and 6E). However, in rats treated with glibenclamide after SAH, local inflammation and reactive astrocytosis were significantly reduced (Figures 6B, 6D, 6F and 6G).

Figure 6.

Glibenclamide reduces SAH-induced inflammation. (A–F) Low power views of inferomedial cortex immunolabeled for TNFα (A, B), p65 (C, D), or GFAP (E, F) from rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (Veh) (A, C and E) or glibenclamide (GLIB) (B, D and F). (G) Quantitative analyses for TNFα, p65, and GFAP in inferomedial cortex of rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (Veh) or glibenclamide (GLIB); 5 rats/group; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

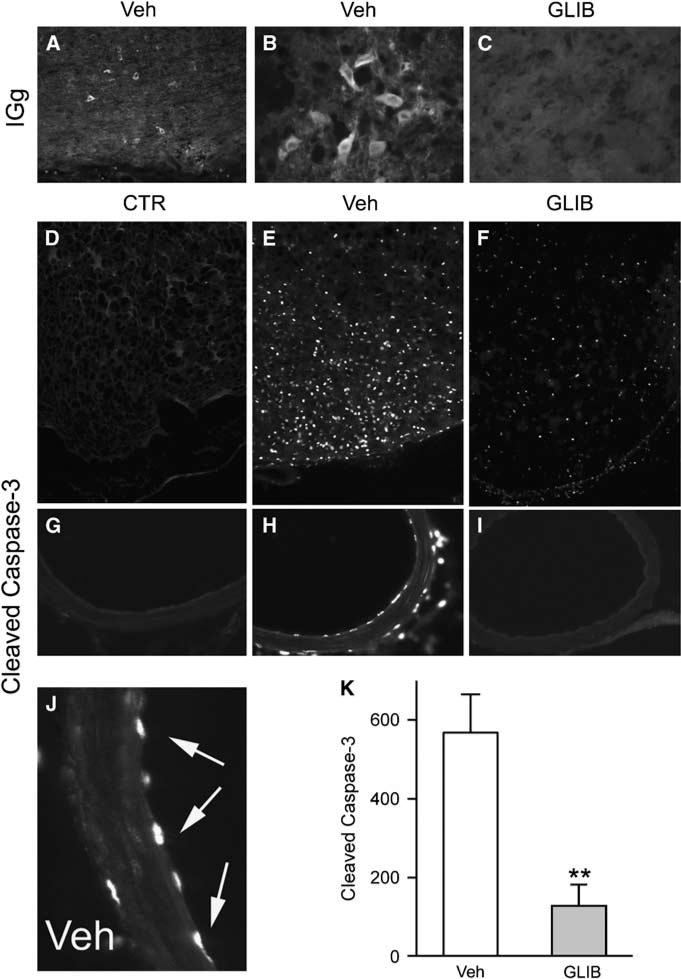

Cell Death

Inflammation can result in cell injury, one manifestation of which is protein endocytosis, which in neurons, is an early marker of critical injury (Simard et al, 2008b). After SAH, extravasated protein was taken up by many neurons in the region (Figures 7A and 7B), consistent with significant neuronal dysfunction. By contrast, in rats administered glibenclamide after SAH, protein endocytosis was essentially absent (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Glibenclamide reduces IgG endocytosis and caspase-3 activation. (A–C) Low power (A) and high power (B, C) views of inferomedial cortex immunolabeled for IgG from rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (A, B) or glibenclamide (C). (D–J) Low power (D–I) and high power (J) views of inferomedial cortex (D–F) or posterior cerebral artery (G–J) immunolabeled for activated (cleaved) caspase-3 from uninjured control rats (D, G) or rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (E, H and J) or glibenclamide (F and I); arrows points to endothelial nuclei that are strongly positive for activated caspase-3. (K) Quantitative analysis for activated caspase-3 in inferomedial cortex of rats 24 h after SAH, administered either vehicle (Veh) or glibenclamide (GLIB); 5 rats/group; **P < 0.01.

Inflammation can also result in activation of signaling pathways that can induce apoptosis (Gupta, 2002; Gaur and Aggarwal, 2003). TNFα induces apoptosis in cultured cerebral endothelial cells through the activation of caspase-3 (Kimura et al, 2003), and activation of caspase-3 has been reported in models of SAH (Aoki et al, 2002; Gules et al, 2003). After SAH, many neurons in the inferomedial cortex exhibited nuclear labeling for activated caspase-3, confirming critical pathologic involvement (Figure 7E versus Figure 7D). Similarly, endothelial cells of the PCA typically showed extensive caspase-3 activation (Figures 7H and 7J versus Figure 7G). However, in animals administered glibenclamide, caspase-3 activation in the PCA was absent in 4 of 5 rats and was minimal in the fifth (Figure 7I), and in parenchymal tissues, caspase-3 activation was significantly reduced (Figures 7F and 7K).

Discussion

In this report, we provide the first evidence that SUR1 is integrally involved in the pathophysiologic response to SAH. We show that Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein were newly upregulated in cortex and in large vessels exposed to subarachnoid blood. Moreover, we show that critical pathologic responses to SAH—an increase in barrier permeability, inflammation and caspase-3 activation—were significantly attenuated by block of SUR1. Previous work has shown involvement of SUR1 or the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel in other conditions affecting the central nervous system, including multiple different models of stroke (Simard et al, 2006, 2008b) and spinal cord injury (Simard et al, 2007b). In previous work, transcriptional upregulation of SUR1 and of the SUR1-regulated channel was attributed to ischemia/hypoxia. By contrast, in the present report, we show that the underlying mechanism governing the response to mild-to-moderate SAH was not hypoxia but inflammation, in particular, upregulation of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNFα. Several mechanisms of secondary injury are believed to be activated after SAH, including delayed effects of global cerebral ischemia, thromboembolism, microcirculatory dysfunction, and cortical spreading depression (Macdonald et al, 2007). The data presented here provide the first molecular evidence that SUR1 is transcriptionally activated and is pathologically involved in the context of inflammation after SAH.

The Model of SAH

The specific contribution of inflammation to the overall response to SAH has previously been difficult to assess, in part because existing animal models of SAH have been explicitly designed to emphasize vasospasm with ischemia/hypoxia, and therefore are inevitably complicated by the coexistence of more than one mechanism of secondary injury. Indeed, the rat filament puncture model was originally designed for study of vasospasm (Schwartz et al, 2000). However, the version of this model that we used was one found to induce only mild-to-moderate SAH associated with low mortality and no significant vasospasm (Schwartz et al, 2000). With this model, we showed that ischemia and hypoxia were not prominent, but that TNFα was upregulated and that NFκB was activated, consistent with an inflammatory response. Unlike most studies using related models with more severe SAH, our approach focusing on mild-to-moderate SAH allowed us to separate out an important pathologic response in vivo that could be duplicated in vitro—TNFα upregulation—and examine the effect of this pathologic response on downstream cellular and molecular events, including those involving SUR1.

One potential weakness of this model is that, by necessity, it produced mild injury that was not associated with any gross neurobehavioral abnormality, making it difficult to examine any neurobehavioral benefit of block of SUR1. The entorhinal cortex affected by SAH in this model is believed to be important for contextual fear learning (Burwell et al, 2004), and future studies are planned to determine whether the severity of injury used here translates into a functional deficit related to this specific cortex, and whether any abnormality may be reduced by inhibiting SUR1.

SUR1 and Barrier Permeability

Disruption of barrier integrity markedly increases permeability to fluid and solute and is the central pathophysiologic mechanism of many inflammatory disease processes involving the brain, including SAH. However, molecular mechanisms linking inflammation to an increase in barrier permeability are poorly understood.

Dynamic control of the endothelial barrier involves complex signaling to the endothelial cytoskeleton and to adhesion complexes between neighboring cells (Lai et al, 2005; Ueno, 2007). The actual barrier is made up of the physical elements of tight junction complexes, the major constituents of which include transmembrane (junctional adhesion molecule-1, occludin, and claudins) and cytoplasmic (zonula occludens-1 and -2, cingulin, AF-6, and 7H6) proteins linked to the actin cytoskeleton (Hawkins and Davis, 2005; Ueno, 2007). The proper cellular location and sealing of tight junctions depends on the scaffolding properties of ZO-1 and its relation to the actin cytoskeleton (Lai et al, 2005; Fanning et al, 2007). Exposure to inflammatory cytokines including TNFα results in rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, ZO-1 disruption, cell retraction, and formation of intercellular gaps (Blum et al, 1997; Wojciak-Stothard et al, 1998; Fanning et al, 2007). To our knowledge, the redistribution of ZO-1 that we observed in the endothelium of the PCA after SAH has not previously been reported. However, this finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the increase in barrier permeability invariably associated with SAH may be tied to a significant disruption of the endothelial actin cytoskeleton.

The data presented here indicate that under pathologic conditions, SUR1 may be important in the complex signaling pathway regulating barrier function. Although not shown here, we suspect that de novo upregulation of SUR1 was associated with expression of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels (Simard et al, 2008a), involvement of which would provide a plausible molecular mechanism to account for the increase in barrier permeability observed after SAH. Biophysically, the channel is a nonselective cation channel that allows passage of all inorganic monovalent cations, but not divalent cations. With typical concentrations of intracellular and extracellular ions, opening of a nonselective cation channel results in sodium influx, resulting in an increase in intracellular sodium concentration and in oncotic cell swelling (Simard et al, 2008a). In many cells, an increase in sodium concentration or a perturbation of cell volume leads to reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and weakening of intercellular tight junctions, leading to an increase in barrier permeability (Rajasekaran et al, 2008). Thus, the data presented here suggest what seems to be a coherent picture linking SAH, TNFα upregulation, NFκB activation, SUR1 upregulation, possible upregulation and opening of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels in endothelial cells, sodium influx, endothelial cell swelling and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement, loss of endothelial tight junction integrity, and formation of vasogenic edema.

SUR1 and Apoptosis

Administration of caspase inhibitors has been found to reduce caspase-3 activation after SAH (Aoki et al, 2002; Gules et al, 2003). However, the present report showing that glibenclamide, which is not a direct inhibitor of caspase, significantly reduced caspase-3 activation, points to SUR1 as an important upstream target leading to apoptosis.

The molecular mechanism by which glibenclamide prevents activation of endothelial caspase-3 after SAH has not been completely determined, but it is reasonable to speculate that inhibition of the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel is involved. As noted above, this channel is responsible for influx of sodium under pathologic conditions (Simard et al, 2008a). Sodium, potassium, and chloride are important during cell death, and are involved in both the signaling and the control of apoptotic volume decrease. Cell depolarization and a rapid increase in intracellular sodium occur early after an apoptotic stimulus (Bortner et al, 2001), with the primary stage of apoptotic volume decrease being characterized by an early exchange of the normal intracellular ion distribution for sodium from 12 to 114 mmol/L, and for potassium from 140 to 30 mmol/L (Bortner et al, 2008). In Jurkat cells, sodium influx is absolutely required for apoptotic cell shrinkage, and pharmacological inhibition of sodium influx completely prevents the onset of anti-Fas-induced apoptosis (Bortner and Cidlowski, 2003). These effects on sodium and potassium ions in Jurkat cells are reproduced by inactivation of sodium/potassium-ATPase (Bortner et al, 2001). Notably, in cells that express the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel, precisely the same effects on cell depolarization and sodium influx are observed with channel opening (Simard et al, 2008a). Further work will be required to explicitly show a direct link between the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel, sodium influx, and endothelial cell apoptosis. Nevertheless, the data presented here are the first to show in vivo that pharmacological inhibition of a molecular mechanism known to be associated with pathologic sodium influx can effectively block apoptosis.

Glibenclamide may act directly on parenchymal cells to exert an antiapoptotic effect, as explained above for endothelial cells. Alternatively, protection may have been indirect, mediated by a reduction in barrier permeability. Vasogenic edema is not only a manifestation of injury, but can itself be injurious. Infusion of plasma or plasma constituents into the brain exacerbates edema formation, upregulates expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes, is associated with DNA fragmentation, necrosis and apoptosis, and causes activation of microglia and infiltration of neutrophils (Yoshida et al, 2002; Wagner et al, 2005). Thus, the activation of caspase-3 in cortical cells after SAH, as well as the increase in TNFα, NFκB, and GFAP, can easily be accounted for by the increase in barrier permeability associated with SAH. Similarly, the decrease in barrier permeability associated with block of SUR1 may be sufficient to account for the decrease caspase-3 activation, as well as the decrease in TNFα, NFκB, and GFAP, observed with glibenclamide treatment.

SUR1-Regulated NCCa-ATP Channel and Capillary Dysfunction

Previous work from this laboratory has linked the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel to various types of edema (Simard et al, 2006, 2007a). Cytotoxic edema (cellular or oncotic edema) has been shown in astrocytes to result from opening of the channel, leading to sodium influx down its electrochemical gradient, which in turn drives chloride influx to maintain electrical neutrality and water influx to maintain osmotic neutrality, which together cause oncotic cell swelling. Ionic edema has been shown to result from opening of the channel in endothelial cells, with luminal and abluminal channel expression resulting in transcapillary passage of sodium from blood to brain parenchyma, which in turn drives transcapillary chloride and water flux, resulting in formation of protein-poor ionic edema in the brain. Here, we postulate that, if sodium flowing into the endothelial cell ceases to exit into the parenchyma, this will give rise to an increase in intraendothelial sodium concentration, resulting in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, thus compromising the integrity of tight junctions and leading to paracellular flow of plasma, resulting in formation of protein-rich vasogenic edema. Finally, we have previously discussed that end-stage endothelial dysfunction involving the channel may result in formation of petechial hemorrhages. We postulated that formation of petechial hemorrhages results from unchecked opening of the channel in endothelial cells, resulting in oncotic death of endothelial cells and total structural failure of the capillary, resulting in extravasation of blood (Simard et al, 2007b). Each of these stages of cellular and capillary endothelial dysfunction has been shown to be significantly ameliorated by pharmacological block of SUR1, with concomitant beneficial effects in stroke (Simard et al, 2006, 2008b), spinal cord injury (Simard et al, 2007b) and now, SAH.

Summary

Here, we present novel findings supporting the hypothesis that SUR1, and possibly the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels, is important in the pathophysiology of SAH. Our data indicate that the potent pharmacological inhibitor, glibenclamide, was highly effective in reducing several short-term effects of SAH, including barrier disruption and caspase-3 activation. Our findings provide new insights into molecular mechanisms responsible for vasogenic edema and cell death after SAH. Much work remains to be performed, however, to elucidate this novel area of pathologic assessment involving SUR1, including identification of the pore-forming subunit of the channel and examination of longer term outcomes. Nevertheless, the data presented here point to SUR1 as a potentially important therapeutic target to ameliorate vasogenic edema and cell death associated with SAH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to JMS from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL082517), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS048260, NS061808), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (Baltimore, MD, USA).

References

- Aoki K, Zubkov AY, Ross IB, Zhang JH. Therapeutic effect of caspase inhibitors in the prevention of apoptosis and reversal of chronic cerebral vasospasm. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:672–7. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2002.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum MS, Toninelli E, Anderson JM, Balda MS, Zhou J, O'Donnell L, Pardi R, Bender JR. Cyto-skeletal rearrangement mediates human microvascular endothelial tight junction modulation by cytokines. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H286–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Cidlowski JA. Uncoupling cell shrinkage from apoptosis reveals that Na+ influx is required for volume loss during programmed cell death. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39176–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Gomez-Angelats M, Cidlowski JA. Plasma membrane depolarization without repolarization is an early molecular event in anti-Fas-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4304–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Sifre MI, Cidlowski JA. Cationic gradient reversal and cytoskeleton-independent volume regulatory pathways define an early stage of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7219–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707809200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Saddoris MP, Bucci DJ, Wiig KA. Corticohippocampal contributions to spatial and contextual learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3826–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill J, Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1341–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning AS, Little BP, Rahner C, Utepbergenov D, Walther Z, Anderson JM. The unique-5 and -6 motifs of ZO-1 regulate tight junction strand localization and scaffolding properties. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:721–31. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur U, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of proliferation, survival and apoptosis by members of the TNF super-family. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1403–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Ivanov A, Ivanova S, Yang JB, Zhou H, Dong Y, Simard JM. Alternative splicing of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I in angiotensin-hypertension: novel mechanism for nitrate tolerance in vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2003;93:805–12. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000097872.69043.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gules I, Satoh M, Nanda A, Zhang JH. Apoptosis, blood–brain barrier, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2003;86:483–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0651-8_99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. A decision between life and death during TNF-alpha-induced signaling. J Clin Immunol. 2002;22:185–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1016089607548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett ML, Anderson CS. Health outcomes 1 year after subarachnoid hemorrhage: an international population-based study. The Australian Cooperative Research on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study Group. Neurology. 2000;55:658–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Schwartz J. Cerebral vasospasm: a consideration of the various cellular mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology. Neurocrit Care. 2004;1:235–46. doi: 10.1385/NCC:1:2:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Schwartz J, Vajkoczy P, Macdonald RL, Pluta RM, Zhang JH. Cerebral vasospasm: looking beyond vasoconstriction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:252–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood–brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:173–85. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmin S, Mathiesen T. Intracerebral administration of interleukin-1beta and induction of inflammation, apoptosis, and vasogenic edema. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:108–20. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.1.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Gules I, Meguro T, Zhang JH. Cytotoxicity of cytokines in cerebral microvascular endothelial cell. Brain Res. 2003;990:148–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CH, Kuo KH, Leo JM. Critical role of actin in modulating BBB permeability. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;50:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Kassell NF, Mayer S, Ruefenacht D, Schmiedek P, Weidauer S, Frey A, Roux S, Pasqualin A. Clazosentan to overcome neurological ischemia and infarction occurring after subarachnoid hemorrhage (CONSCIOUS-1). Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 dose-finding trial. Stroke. 2008 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519942. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519942 (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Pluta RM, Zhang JH. Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the emerging revolution. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:256–63. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SA, Kreiter KT, Copeland D, Bernardini GL, Bates JE, Peery S, Claassen J, Du YE, Connolly ES., Jr Global and domain-specific cognitive impairment and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2002;59:1750–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000035748.91128.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megyeri P, Abraham CS, Temesvari P, Kovacs J, Vas T, Speer CP. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha constricts pial arterioles and increases blood–brain barrier permeability in newborn piglets. Neurosci Lett. 1992;148:137–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90823-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty MA, Lo EH. Junctional complexes of the blood–brain barrier: permeability changes in neuroinflammation. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:311–23. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran SA, Beyenbach KW, Rajasekaran AK. Interactions of tight junctions with membrane channels and transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:757–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholler K, Trinkl A, Klopotowski M, Thal SC, Plesnila N, Trabold R, Hamann GF, Schmid-Elsaesser R, Zausinger S. Characterization of microvascular basal lamina damage and blood–brain barrier dysfunction following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1142:237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AY, Masago A, Sehba FA, Bederson JB. Experimental models of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat: a refinement of the endovascular filament model. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;96:161–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sercombe R, Dinh YR, Gomis P. Cerebrovascular inflammation following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;88:227–49. doi: 10.1254/jjp.88.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Bhatta S, Ivanova S, Melnitchenko L, Tsymbalyuk N, West GA, Gerzanich V. Newly expressed SUR1-regulated NC(Ca-ATP) channel mediates cerebral edema after ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12:433–40. doi: 10.1038/nm1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Gerzanich V. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2007a;6:258–68. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Tsymbalyuk O, Ivanov A, Ivanova S, Bhatta S, Geng Z, Woo SK, Gerzanich V. Endothelial sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated NC Ca-ATP channels mediate progressive hemorrhagic necrosis following spinal cord injury. J Clin Invest. 2007b;117:2105–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI32041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Woo SK, Bhatta S, Gerzanich V. Drugs acting on SUR1 to treat CNS ischemia and trauma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008a;8:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard JM, Yurovsky V, Tsymbalyuk N, Melnitchenko L, Ivanova S, Gerzanich V. Protective effect of delayed treatment with low-dose glibenclamide in three models of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008b doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522409. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatovic SM, Dimitrijevic OB, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV. Inflammation and brain edema: new insights into the role of chemokines and their receptors. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006;96:444–50. doi: 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanimirovic D, Satoh K. Inflammatory mediators of cerebral endothelium: a role in ischemic brain inflammation. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:113–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez JI, Tarr RW, Selman WR. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:387–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M. Molecular anatomy of the brain endothelial barrier: an overview of the distributional features. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1199–206. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Dean C, Beiler S, Bryan DW, Packard BA, Smulian AG, Linke MJ, de Courten-Myers GM. Plasma infusions into porcine cerebral white matter induce early edema, oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression and DNA fragmentation: implications for white matter injury with increased blood–brain-barrier permeability. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:149–55. doi: 10.2174/1567202053586785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak-Stothard B, Entwistle A, Garg R, Ridley AJ. Regulation of TNF-alpha-induced reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and cell–cell junctions by Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 in human endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:150–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<150::AID-JCP17>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Chen C, Hu Q, Yang X, Lei J, Yang L, Wang K, Qin L, Zhou C. The role of p53 in brain edema after 24 h of experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in a rat model. Exp Neurol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.006 (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Tanaka M, Okamoto K. Immunoglobulin G induces microglial superoxide production. Neurol Res. 2002;24:361–4. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]