Abstract

The β3-adrenergic receptor (β3AR) is an essential regulator of metabolic and endocrine functions. A major cellular and clinically significant consequence of β3AR activation is the substantial elevation in interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels. Although the β3AR-dependent regulation of IL-6 expression is well established, the cellular pathways underlying this regulation have not been characterized. Using a novel method of homogenous reporters, we assessed the pattern of activation of 43 transcription factors in response to the specific β3AR agonist CL316243 in adipocytes, cells that exhibit the highest expression of β3ARs. We observed a unique and robust activation of the CRE-response element, suggesting that IL-6 transcription is regulated via the Gs-protein/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) but not nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. However, pretreatment of adipocytes with pharmacologic inhibitors of PKA pathway failed to block β3AR-mediated IL-6 up-regulation. Additionally, stimulation of adipocytes with the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) agonist did not induce IL-6 expression. Instead, the β3AR-mediated transcription of IL-6 required activation of both the p38 and PKC pathways. Western blot analysis further showed that transcription factors CREB and ATF-2 but not ATF-1 were activated in a p38- and PKC-dependent manner. Collectively, our results suggest that while stimulation of the β3AR leads to a specific activation of CRE-dependent transcription, there are several independent cellular pathways that converge at the level of CRE-response element activation, and in the case of IL-6 this activation is mediated by p38 and PKC but not PKA pathways.

Keywords: Cytokine, p38, PKC, obesity, inflammation

1. Introduction

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine that modulates immune response, inflammation, nervous, hematopoietic, and endocrine systems (Kamimura et al., 2003; Kishimoto, 2005). Although IL-6 has a widespread tissue distribution, previous reports have indicated that up to 30% of circulating IL-6 is derived from adipose tissue (Fried et al., 1998; Mohamed-Ali et al., 1997). Consistent with these reports, plasma IL-6 levels are markedly elevated in obese subjects (Vgontzas et al., 1997). Obesity is closely associated with chronic low-grade inflammation characterized by abnormal production of cytokines and acute phase proteins (Hotamisligil, 2006; Wellen and Hotamisligil, 2005). The inflammatory response that emerges in the presence of obesity seems to be triggered by and predominantly reside in adipose tissue. Additionally, the production of IL-6 is well documented in different adipose tissues and adipocyte models (Burysek and Houstek, 1997; Fain et al., 2004; Hoch et al., 2008; Mohamed-Ali et al., 2001; Path et al., 2001; Skurk et al., 2007; Vicennati et al., 2002).

Both white (WAT) and brown (BAT) adipose tissues are innervated by sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (Fliers et al., 2003; Slavin and Ballard, 1978; Wirsen and Hamberger, 1967). Although sympathetic innervation is less abundant in WAT than in BAT, norepinephrine turnover in WAT can be significant in the immediate vicinity of nerve terminals, particularly in response to stress (Bamshad et al., 1998; Collins et al., 2004). In rodents SNS activation during stress has been associated with elevated plasma IL-6 levels (Takaki et al., 1994; Zhou et al., 1993). Similarly, in humans a positive correlation has been observed between exercise-induced peak plasma epinephrine or norepinephrine and IL-6 levels (Papanicolaou et al., 1996). Epinephrine and norepinephrine regulate IL-6 release from adipocytes predominantly via activation of β-adrenergic receptors (βARs). In vitro, administration of norepinephrine, the general βAR agonist isoproterenol, or the selective β3AR agonist CGP-12117 stimulated IL-6 expression in murine brown adipocytes (Burysek and Houstek, 1997), and isoproterenol elevated IL-6 production in human breast adipocytes (Path et al., 2001). In vivo, administration of β2 or β3 agonists in mice or infusion of isoproterenol in human volunteers resulted in heightened plasma IL-6 concentrations (Mohamed-Ali et al., 2001). Although β3AR-dependent regulation of IL-6 expression is well established, the intracellular signaling pathways underlying this regulation have not been characterized.

Activation of the β3AR by epinephrine, norepinephrine, or specific agonists typically results in the Gs-dependent activation of adenylate cyclase, increases in intracellular cAMP, and stimulation of protein kinase A (PKA) (Guan et al., 1995; Lindquist et al., 2000; Soeder et al., 1999). PKA, in turn, regulates expression of various genes via phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) which binds to cAMP-responsive element (CRE) sites in the promoter region of cAMP-responsive genes (Rockman et al., 2002). Recently, cAMP has been shown to activate not only PKA but also a class of cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) cation channels and a small family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) known as exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (Epacs) (de Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998b).

New layers of complexity have been added to the field of β3AR signaling with the discovery that β3ARs couple to Gi as well as Gs. In adipocytes, stimulation of the β3AR activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) via the Gi-dependent pathway (Cao et al., 2000; Gerhardt et al., 1999; Soeder et al., 1999). However, discrepant reports from other groups suggest that β3AR-dependent ERK1/2 activation is mediated via the Gs/PKA pathway (Lindquist et al., 2000; Mizuno et al., 1999). In addition to ERK1/2, activation of β3ARs in adipocytes has been shown to stimulate another mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 through the classical Gs- and PKA-dependent pathway (Cao et al., 2001; Moule and Denton, 1998), although an obligatory role of PKA in p38 phosphorylation was not confirmed in another work (Mizuno et al., 2002). Finally, activation of β3ARs leads to stimulation of one more major family of signaling enzymes- protein kinases C (PKCs). It has been demonstrated that β3AR agonists increase glucose uptake in brown adipocytes stimulating conventional and novel PKCs (Chernogubova et al., 2004). Thus, β3ARs exhibit a dynamic capacity to stimulate divergent signaling pathways.

To elucidate the signaling pathways controlling IL-6 production in white adipocytes, we employed a novel method of homogenous reporters (Romanov et al., 2008) and assessed the activation pattern of 43 transcription factors in response to the β3AR-specific agonist CL316243. We observed a unique and robust activation of the CRE-response element, but not NF-κB which is a pivotal regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Baldwin, 1996). CRE activation suggested regulation of IL-6 transcription via Gs/cAMP/PKA activity. However, subsequent experiments demonstrated that IL-6 expression is not mediated through PKA or NF-κB pathways, but instead requires activation of p38- and PKC-dependent signaling mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture

The C3H10T1/2, 3T3-L1, and HEK 293 cells were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection Center (Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in DMEM (Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and 1x penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) under a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. 3T3-L1 fibroblast cells were treated with 0.5 mM IBMX (Sigma), 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma), and 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma) to initiate adipogenesis as described previously (Mizuno et al., 1999). C3H10T1/2 adipogenesis was induced by incubating cells in growth media containing 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM rosiglitazone, and 10 μg/ml insulin for 2 days, after which cells were allowed to differentiate in growth media with two more boosts of 1 μM rosiglitazone and 10 μg/ml insulin. After more than 90% of cells became differentiated, the media containing inducers of differentiation was replaced with growth medium without inducers, and cells were maintained for two more days in culture. Then adipocytes were treated with various reagents.

2.2. Factorial homogenous reporter system

The mouse pluripotent fibroblasts C3H10T1/2 were plated at subconfluent density in 6-well plates and then transfected the next day with the Factorial reporter library as described previously (Romanov et al., 2008). The C3H10T1/2 cells were selected because we found that they provide a unique fibroblast cell system that will continue to differentiate into adipocytes after transfection, a critical step required for the Factorial application. After appropriate adipocyte differentiation, the cells were stimulated with various reagents, total cellular RNA was extracted and processed according to the Factorial detection protocol and quantified as described previously (Romanov et al., 2008).

2.3. Drugs and treatment

CL316243, ICI 118,551, Betaxolol, SR59230A, RO31-8220, PTX, and 8CPT-2’-O-Me-cAMP were obtained from Tocris Cookson, Ellisville, MI. NBD peptide, MG-132, U0126, and SB203580 were purchased from Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA. CTX was bought from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA. An aliquot of each drug solution was added to the medium, and the final concentration of the vehicle in the medium was adjusted to 0.1% (v/v). The control medium contained the same amount of the vehicle. For inhibitor experiments, cells were pretreated with the indicated drug for 1 h prior. Dose-response curves were established for the agonist and antagonist. Doses within one log unit of the ED50 or ID50 were used for all in vitro experiments. The effectiveness of the chosen inhibitor doses was confirmed in our previous report (Tan et al., 2007).

2.4. Detection of IL-6 by real-time PCR and ELISA

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Prior to reverse transcription, RNA was treated with 2 units of TURBO DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 37°C for 30 min. Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript III (Carlsbad, CA, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. IL-6 transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System. The expression of cytokine mRNAs was normalized to the relative abundance of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Fold induction was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Experiments were performed in quadruplicate. IL-6 protein was determined in the culture supernatant of adipocytes using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Plasmids and transfections

Reporter vectors containing specific cis-acting DNA sequence fused to secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP), pCRE-SEAP, pAP-1-SEAP, pC/EBPβ-SEAP, pNF-κB-SEAP and pETS-SEAP, were purchased from Clontech, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA). Mouse β3-AR clone (GB#BC132000) was purchased from I.M.A.G.E. Consortium Collection (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) and subcloned into pCMV-SPORT6 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 3rd exon of the clone (nucleotides 1239 to 1327) has been replaced with the PCR amplified cDNA fragment corresponding to 3rd exon of the major β3-AR isoform NM_013462 (nucleotides 1975 to 2042). The functional activity of the clone has been confirmed in transfection experiments. HEK 293 cells were transfected with Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For normalization of transfection efficiency, cells were co-transfected with a β-galactosidase plasmid (Clontech). Cell stimulation experiments were performed 24 h after transfection. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.6. SEAP activity assay

The culture medium was changed to remove the accumulated SEAP prior to treatment of cells with CL316243. The cells were incubated with CL316243 for 6, 12 or 24 h. Culture medium was collected and subjected to SEAP activity assays. The SEAP activity in the culture medium was measured with a Phospha-Light assay kit (Tropix, Foster City, CA), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.7. Western blot analyses

Cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). The amount of protein in the cell lysates were quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins were resolved on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) NuPAGE Novex Gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Piscatawy, NJ). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h and then probed with the specific antibodies at 4°C overnight. Protein expression was determined with the specific primary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies to p-p38, pPKCs, pATF-2 and pCREB were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, and antibodies to p-PKCε were received from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. The pCREB antibody also detects the pATF-1 at a different size. β-actin was used as the loading control. Antibodies were detected with corresponding horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using Enhanced Chemiluminescent (ECL) reagent (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and signals captured using the ImageQuant ECL system (Amersham). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by performing an analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. β3AR activation leads to IL-6 increase in white adipocytes

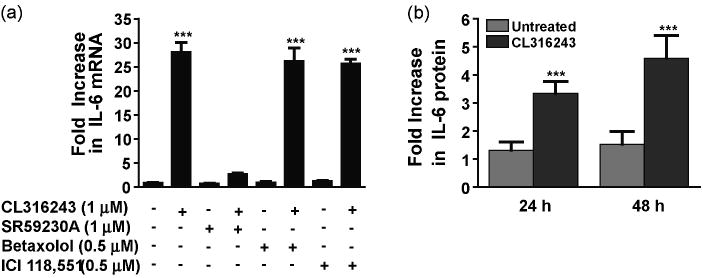

We first sought to confirm that β3AR stimulation can modulate IL-6 mRNA expression in the 3T3-L1 adipocyte cell model (Green and Kehinde, 1976). 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with CL316243, a specific β3 agonist (Bloom et al., 1992), and real-time quantitative PCR was used to quantify the level of mRNA transcripts present. Treatment of 3T3-L1 cells with CL316243 (1 μM) resulted in about 30-fold increase in IL-6 transcripts, when compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1a). In line with previously reported correlation between up-regulation of IL-6 mRNA and protein secretion (Burysek and Houstek, 1997; Path et al., 2001), this increase in IL-6 mRNA expression was accompanied by a 3.5- and 4.8-fold increase in IL-6 protein secretion by 24 and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 1b). Similarly, an up-regulation of IL-6 expression was also observed in the murine white adipocytes C3H10T1/2 (results not shown). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 transcripts was blocked by the specific β3AR antagonist SR59230A (1 μM), but not by the specific β1AR antagonist betaxolol (0.5 μM) or the specific β2AR antagonist ICI118,551 (0.5 μM) (Fig. 1a). These results indicate that β3AR stimulation leads to a significant up-regulation of IL-6 expression in white adipocytes.

Fig. 1.

β3AR stimulation up-regulates IL-6 production in adipocytes. 3T3-L1 cells treated with the β3AR-agonist CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min) showed a significant increase in IL-6 mRNA. The CL316243-induced increase in cytokine transcripts was completely blocked by pre-treatment with SR59230A (1 μM for 1 h) but not with betaxolol (0.5 μM for 1 h) or ICI118,551 (0.5 μM for 1 h) (a). 3T3-L1 cells treated with the β3AR-agonist CL316243 (1 μM for 24 and 48 h) showed a significant increase in IL-6 protein measured in cell supernatant (b). ***P<0.001 different from untreated.

3.2. β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression is PKA- and Epac- independent

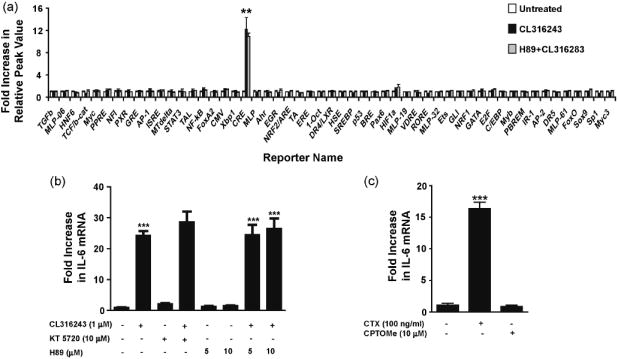

To identify the regulatory pathways involved in β3AR-mediated signaling, we used a recently described homogeneous reporter system termed Factorial (Romanov et al., 2008). The system comprises 43 cis-regulatory reporter transcription units enabling simultaneous functional profiling of multiple transcription factors present in the cell. We found that of all the Factorial reporters, the CRE reporter was the only one whose activity was strongly induced (12-fold induction) by CL316243 (1 μM) in C3H10T1/2 adipocytes (Fig. 2a). Activation of the CRE reporter in the homogenous reporter experiment together with the presence of a functional CRE element in the promoter region of IL-6 (Ammit et al., 2002; Edwards et al., 2007; Ray et al., 1988) led to the expectation that the cAMP/PKA/CREB cascade underlies β3AR-mediated IL-6 regulation. Surprisingly, however, stimulation of the CRE reporter in adipocytes by CL316243 was not inhibited by the PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μM) (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, IL-6 mRNA expression was not blocked in 3T3-L1 cells pretreated with the PKA inhibitors H89 or KT5720 (Fig. 2b), suggesting that the β3AR-dependent signaling pathway(s) leading to IL-6 up-regulation are distinct from the cAMP/PKA regulatory pathway.

Fig. 2.

β3AR-induced IL-6 expression is PKA- and Epac-independent. C3H10T1/2 cells were pretreated with H89 (10 μM for 1 h) prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 2 h). The CL316243-induced activation of the CRE reporter was not inhibited by H89 in the homogenous reporter assay (a). 3T3-L1 cells were treated with KT5720 (10 μM) or H89 (5-10 μM) for 1 h prior to treatment with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 mRNA was not inhibited by KT5720 or H89 (b). Treatment of 3T3-L1 with CTX (100 ng/ml for 4 h) led to increases in IL-6 transcript, while treatment with the Epac agonist 8CPT-2’-O-Me-cAMP (CPTOMe) (10 μM for 45 min) did not enhance IL-6 expression (c). ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 different from untreated.

We further examined the possibility that cAMP could activate IL-6 production through the PKA-independent Epac (guanine nucleotide exchange factors directly activated by cAMP) pathway (de Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998b). Epac proteins bind cAMP with high affinity and activate the Ras superfamily small GPTases Rap1 and Rap2. To determine if Epac activation results in IL-6 production, 3T3-L1 cells were treated with the Epac agonist, 8CPT-2’-O-Me-cAMP (CPTOMe, 10 μM), and the level of IL-6 mRNA measured by real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 2c). Treatment of cells with CPTOMe failed to promote increased IL-6 mRNA levels. However, similar to previous reports, treatment of 3T3-L1 cells with cholera toxin (CTX), an activator of Gs proteins (Cassel and Selinger, 1977), did lead to a 16-fold increase in IL-6 mRNA levels (Fig. 2c). Together, these data indicate that β3AR-mediated IL-6 production in white adipocytes depends on CRE activation but not PKA or Epac activation.

3.3. β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression is NF-κB-independent

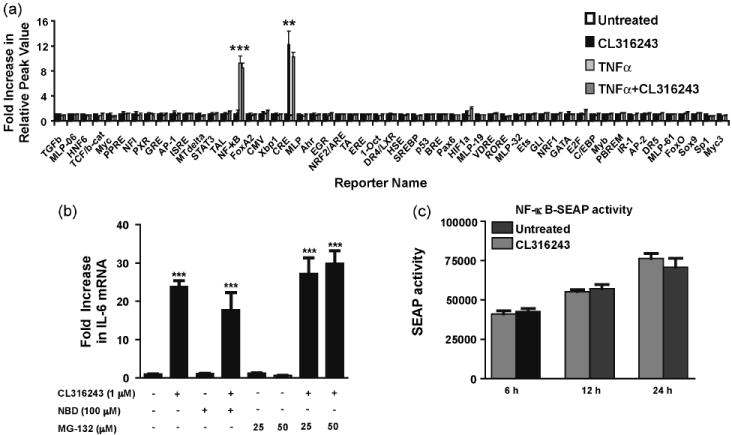

Transcription factor NF-κB is a pivotal regulator of inflammation and has been shown to play a central role in the transcriptional regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Baldwin, 1996). Therefore, we sought to investigate whether NF-κB stimulation is required for β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression. In a homogenous reporter system, NF-κB reporter activity was not affected by CL316243 (1 μM) treatment, though it was strongly induced by TNFα (10 ng/ml) which served as a positive control for NF-κB activation (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

β3AR-induced IL-6 expression is not mediated by NF-κB pathway. C3H10T1/2 cells were treated with CL316243 (1 μM) and TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 2 h. In the homogenous reporter assay, CL316243 didn’t activate the NF-κB reporter, while TNFα did (a). 3T3-L1 cells were pre-treated with NBD (100 μM) or MG-132 (25-50 μM) for 1 h prior to treatment with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 mRNA was not inhibited by NBD or MG-132 (b). SEAP activity was assayed from the culture media of HEK 293 cells co-transfected with the pNF-κB-SEAP reporter construct and β3AR expression vector. No significant increase in SEAP activity was observed at 6, 12 and 24 h post-treatment with CL316243 (1 μM) (c). ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 different from untreated.

As the homogenous reporter assay results did not suggest a contribution of NF-κB in CL316243-dependent IL-6 up-regulation, we confirmed this conclusion by independent approaches. NF-κB activity can be inhibited using either NEMO binding peptide (NBD), which binds to and inactivates IKKγ thereby blocking the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB (May et al., 2000; Yamaoka et al., 1998), or MG-132, a proteosome inhibitor (Fenteany et al., 1995; Myung et al., 2001). Pre-treatment of 3T3-L1 cells with NBD (100 μM) or MG-132 (25 and 50 μM) prior to β3AR stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM) did not block IL-6 up-regulation (Fig. 3b) confirming the mechanism is NF-κB-independent.

In agreement with these results and data from homogenous reporter assay, human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (HEK 293) co-transfected with the pNF-κB-SEAP reporter vector and β3AR expression construct did not show significant changes in SEAP reporter activity following CL316243 (1 μM) treatment (Fig. 3c). Thus, all these experiments strongly indicate that β3AR stimulation does not result in NF-κB activation.

3.4. Role of MAPK pathways in β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression

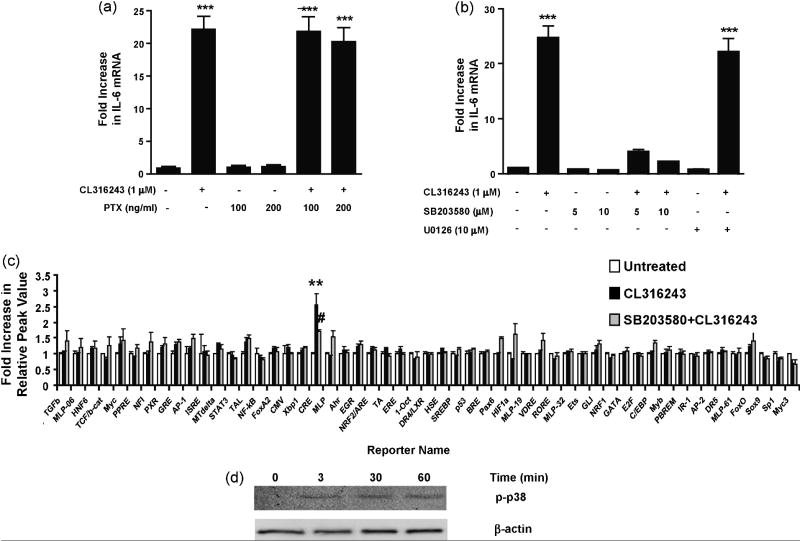

It has been reported that β3ARs can activate ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK cascades through interchangeable coupling to both Gi and Gs (Collins et al., 2004). Although findings from various studies differ, β3AR coupling with Gi proteins has been implicated in phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Cao et al., 2000; Gerhardt et al., 1999; Robidoux et al., 2006; Soeder et al., 1999). We used pertussis toxin (PTX), which ADP-ribosylates and inactivates Gi proteins, to test the plausible contribution of this Gi-mediated pathway to β3AR-mediated IL-6 production. The CL316243-induced IL-6 mRNA up-regulation was not inhibited in cells pretreated with the PTX (Fig. 4a), excluding the role of Gi-dependent signaling in the regulation of IL-6 expression.

Fig. 4.

β3AR-induced IL-6 expression is Gi- and ERK1/2-independent and mediated by p38 signaling pathway. 3T3-L1 cells were pretreated with PTX (100 ng/ml and 200 ng/ml for 1 h) prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 transcripts was not blocked by PTX (a). 3T3-L1 cells were pretreated with either U0126 (10 μM) or SB203580 (5-10 μM) for 1 h prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 transcripts was blocked by SB203580, but not U0126 (b). C3H10T1/2 cells were pretreated with SB203580 (10 μM for 1 h) prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced activation of CRE reporter was inhibited by SB203580 in homogenous reporter assay (c). The cells lysates were also subjected to Western blot analyses with antibodies to p-p38. Increased phosphorylation of p38 was observed at 3, 30 and 60 min post-treatment with CL316243. β-actin was used as the loading control (d). ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 different from untreated. #P<0.05 different from CL316243-treated.

We next examined whether inhibition of the MAPK pathways could block the β3AR-dependent IL-6 production. Pretreatment of 3T3-L1 cells with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (5-10 μM) blocked the CL316243-induced increase in IL-6 mRNA level (Fig. 4b). In contrast, pretreatment with ERK inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) had no effect on CL316243-induced IL-6 expression (Fig. 4b). In the homogenous reporter assay, activation of the CRE reporter by CL316243 was also blocked by pretreatment with SB203580 (10 μM; Fig. 4c). Additionally, p38 phosphorylation following CL316243 treatment was observed in cell lysates by Western blot analyses (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these results indicate that while no contribution of Gi-dependent ERK1/2 stimulation was observed, p38 activation is required for β3AR-mediated IL-6 production.

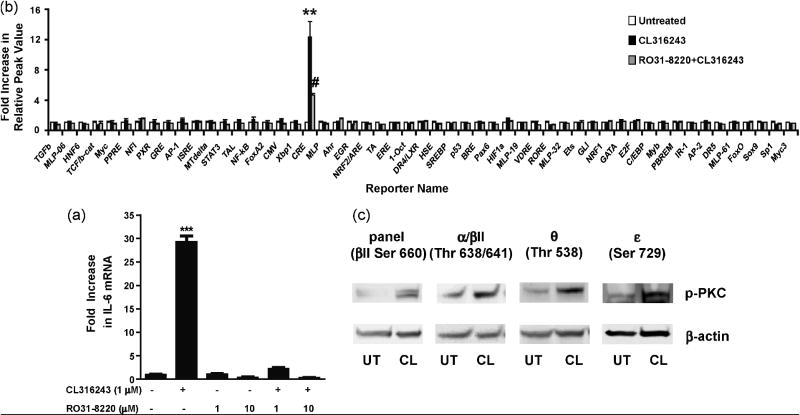

3.5. Role of the PKC pathway in β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression

Previous work has demonstrated that protein kinases C (PKCs) are essential for β3AR-mediated glucose uptake regulation (Chernogubova et al., 2004). Thus, we sought to determine the effect of PKC inhibition on β3AR-mediated IL-6 production using the specific PKC inhibitor RO31-8220 which blocks conventional (α, β, γ) and novel (ε and θ) PKC isoforms (Wilkinson et al., 1993; Yuan et al., 2002). Pretreatment with RO31-8220 (1 and 10 μM) completely inhibited CL316243-induced IL-6 mRNA expression in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 5a) and significantly inhibited CL316243-mediated activation of the CRE reporter in the homogenous reporter assay (Fig. 5b). Additionally, CL316243-mediated phosphorylation of several PKC subtypes was detected applying an antibody specific for a panel of PKCs (α, βI, βII, δ, ε, and η) phosphorylated at C-terminal residue homologous to serine 660 of PKCβII. In a subsequent attempt to identify individual PKC isoforms activated by CL316243 treatment, phosphorylation of PKC α/βII, θ, and ε was observed with the use of isoform-specific antibodies (Fig. 5c). These findings indicate that conventional and novel isoforms of PKC play a significant role in β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression.

Fig. 5.

β3AR-induced IL-6 expression is dependent on the PKC signaling pathway. 3T3-L1 cells were pretreated with RO31-8220 (1-10 μM) for 1 h prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). The CL316243-induced up-regulation of IL-6 transcripts was blocked by RO31-8220 (a). C3H10T1/2 cells were pretreated with RO31-8220 (10 μM for 1 h) prior to stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 2 h). The CL316243-induced activation of CRE reporter was inhibited by RO31-8220 in the homogenous reporter assay (b). The cells lysates were also subjected to Western blot analyses with antibodies to pPKCpan (βII Ser660), pPKCα/βII (Thr638/641), pPKCθ (Thr538), and pPKCε (Ser729). Increased phosphorylation of PKCα/βII was observed at 30 sec and PKCpan, PKCθ and PKCε 45 min post-treatment with CL316243. β-actin was used as the loading control (c). ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 different from untreated. #P<0.05 different from CL316243-treated.

3.6. Stimulation of β3AR leads to the phosphorylation of transcription factors CREB and ATF-2

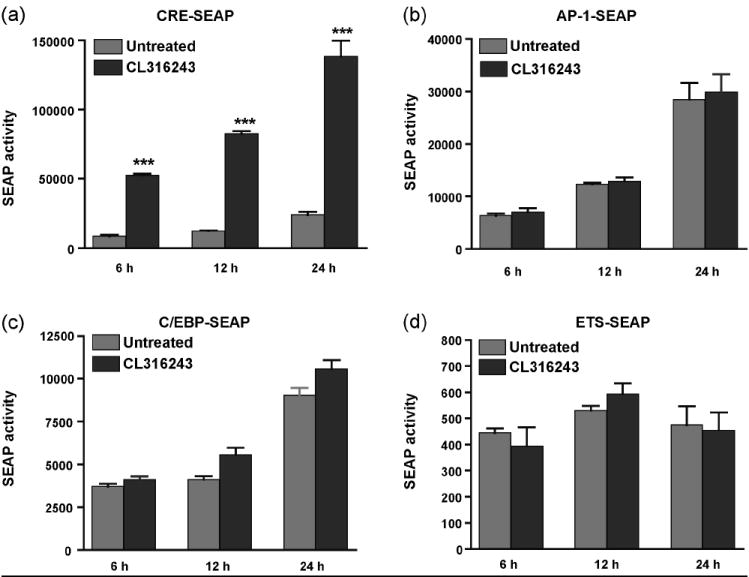

To determine transcription factors that mediate β3AR-dependent IL-6 expression, the transcription factors which bind to the CRE-response element were investigated. First, to confirm the results of the homogeneous reporter assay, a pCRE-SEAP reporter vector with the CRE-response element was co-transfected into HEK293 cells with a β3AR expression construct (Fig.6a). Cells were treated with CL316243, and SEAP activity was measured over a 24-hour period. In agreement with the initial screening results, we observed a 5- to 6-fold increase in CRE-dependent SEAP expression (Fig. 6a). To confirm that other transcription factors most commonly associated with activation of PKC or p38 pathways are not activated in response to β3AR stimulation (Buchwalter et al., 2004; Isakov and Altman, 2002; Trautwein et al., 1993), analogues experiments were conducted with pAP-1-SEAP, pC/EBPβ-SEAP, and pETS-SEAP reporter vectors. Again, in full agreement with the homogeneous reporter assay, no significant differences in AP-1, C/EBPβ or ETS activities were found (Fig. 6b-d).

Fig. 6.

Stimulation of β3ARs results in up-regulation of the reporter construct containing the CRE site. HEK 293 cells were transiently co-transfected with pCRE-SEAP (a), pAP1-SEAP (b), pC/EBPβ-SEAP (c), or pETS-SEAP (d) reporter constructs along with the β3AR expression vector. 24 h after transfection, media was changed, and cells were stimulated with CL316243 (1 μM) for 6, 12 and 24 h. Significant increase in SEAP activity was observed with pCRE-SEAP construct only. ***P<0.001 different from untreated.

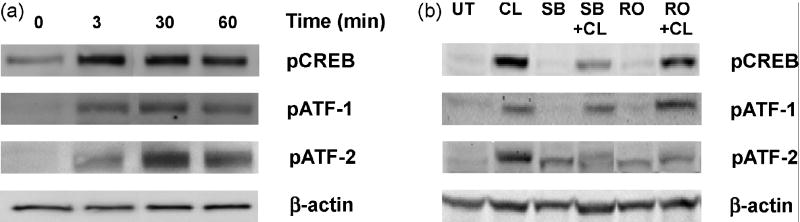

Transcription factors that specifically recognize the CRE-response element include the CREB/ATF family (Hai and Hartman, 2001). We examined the phosphorylation states of CREB, ATF-1, and ATF-2 transcription factors in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. An increased phosphorylation of CREB, ATF-1, and ATF-2 was observed following CL316243 treatment (Fig. 7a). Pretreatment of cells with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10 μM) remarkably reduced the phosphorylation of both CREB and ATF-2, while administration of the PKC inhibitor RO31-8220 (10 μM) decreased reduced phosphorylation of ATF-2 only (Fig. 7b). In contrast, the phosphorylation of ATF-1 was unaffected by either SB203580 or RO31-8220. Thus, our results suggest that the β3AR-dependent up-regulation of IL-6 transcription in adipocytes is mediated by the transcription factors CREB and ATF-2.

Fig. 7.

Effect of β3AR agonist stimulation on phosphorylation of CREB, ATF-1, and ATF-2. 3T3-L1 cells were stimulated with CL316243 (1 μM) for 3, 30, and 60 min, then cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses with antibodies to pCREB, pATF-1, and pATF-2. CL316243 stimulation increased phosphorylation of pCREB, pATF-1, and pATF-2 (a). 3T3-L1 cells were pretreated with SB203580 (10 μM for 1h) or RO31-8220 (10 μM for 1 h) before stimulation with CL316243 (1 μM for 45 min). CL316243-induced phosphorylation of CREB and ATF-2 was attenuated in the presence of SB203580, while ATF-2 phosphorylation was also decreased in the presence of RO31-8220, although non-specific phosphorylation of ATF-2 also has been observed in presence of inhibitors alone. ATF-1 phosphorylation was not affected by inhibitor treatment. β-actin was used as the loading control (b).

4. Discussion

Activation of β3ARs in adipocytes and adipose tissue results in increased production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 (Burysek and Houstek, 1997; Mohamed-Ali et al., 2001; Path et al., 2001). In the present study, we elucidated the signaling pathways underlying β3AR-mediated regulation of IL-6 production in white adipocytes. In view of previous reports that circulating IL-6 concentrations are elevated in obesity and that adipose tissue releases up to 30% of total IL-6 in the circulation (Fried et al., 1998; Mohamed-Ali et al., 1997; Vgontzas et al., 1997), the molecular mechanisms contributing to enhanced production of this pro-inflammatory cytokine may play an active role in generating low grade chronic inflammation in obesity.

Here, we demonstrated that β3AR stimulation in white adipocytes dramatically increases both mRNA and protein levels of IL-6 (30- and 5-fold, respectively). Adrenergic regulation of IL-6 release has been reported in several other cell types, including macrophages (Tan et al., 2007), hepatocytes (Jung et al., 2000), astrocytes (Norris and Benveniste, 1993), cardiac fibroblasts (Yin et al., 2006), and endothelial cells (Gornikiewicz et al., 2000), although the relative contribution of these tissues to circulating IL-6 concentrations is unknown. Adipose tissue is innervated by postganglionic sympathetic nerves releasing norepinephrine, which promote increased IL-6 levels in humans and animal models (Papanicolaou et al., 1996; Takaki et al., 1994; Zhou et al., 1993). Thus, elevated systemic concentrations of IL-6 associated with obesity could be related to higher SNS activity as well as increased adipose tissue mass in obese subjects (Tentolouris et al., 2006).

To examine the transcriptional pathways involved in β3AR-mediated signaling, we utilized a novel homogeneous reporter system (Romanov et al., 2008) enabling quantitative assessment of multiple transcription factor activities in a eukaryotic cell. The robust activation of a single CRE reporter along with the presence of a functional CRE element in the promoter region of IL-6 (Ammit et al., 2002; Edwards et al., 2007; Ray et al., 1988), suggested that the cAMP/PKA/CREB cascade underlies β3AR-mediated IL-6 production. Nevertheless, specific PKA inhibitors failed to block either the IL-6 mRNA up-regulation induced by CL316243 in adipocytes or the CRE activation in the homogenous reporter assay. Thus, our findings suggest that the signaling mechanisms required for β3AR-mediated IL-6 production do not involve the PKA pathway.

PKAs were considered to be the major effectors of cAMP until the recent discovery of Epacs, exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP, which have been shown to activate the small G proteins Rap1 and Rap2 (de Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998b). Stimulation of the β2AR has been reported to induce PKA-independent cell adhesion through Epac and Rap1 (de Rooij et al., 1998). Epac activation produces an inhibitory effect on PKB phosphorylation in rat white adipocytes (Zmuda-Trzebiatowska et al., 2007) while does not affect glucose uptake in brown adipocytes (Chernogubova et al., 2004). Using the Epac-specific agonist CPTOMe, we found no evidence for involvement of an Epac pathway in activation of IL-6 release in our experiments, although CTX treatment significantly elevated IL-6 mRNA expression. These results suggest that β3AR-induced IL-6 production could be mediated by a novel cAMP pathway through PKA- and Epac-independent mechanism. Indeed, several atypical cAMP binding proteins have been described, including the cAMP receptor which regulates development in Dictyostelium discoideum (Klein et al., 1988) and cyclic nucleotide gated channels from olfactory neurons (Goulding et al., 1992). Whether atypical cAMP pathways are involved in IL-6 secretion in adipocytes still needs further investigation. Interestingly, β3AR-mediated IL-6 production was also independent from another pivotal regulator of cytokine expression, NF-κB (Baldwin, 1996). The PKA- and NF-κB-independent nature of β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression in adipocytes is in line with similar reports which have been recently published regarding β2AR-mediated cytokine production. Secretion of IL-6 after β2AR stimulation is PKA-independent and p38-driven in mouse cardiac fibroblasts (Yin et al., 2006), while β2AR-mediated release of IL-6 and IL-1β is PKA- and NF-κB-independent in macrophages (Tan et al., 2007).

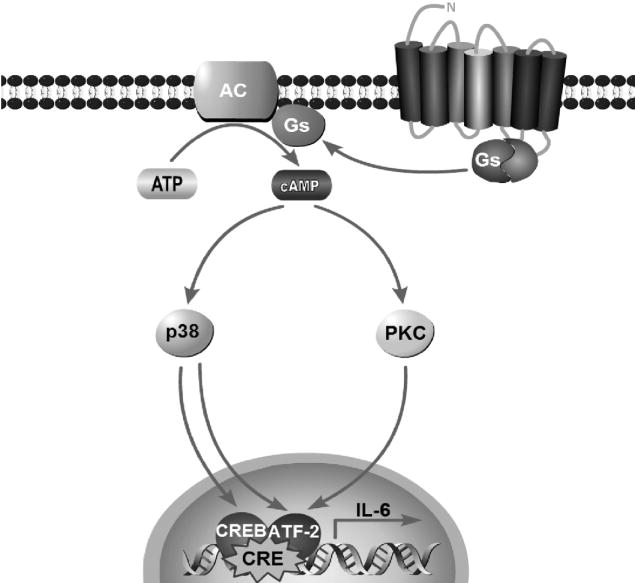

It has been reported that β3ARs can interchangeably couple to both Gs and Gi and activate ERK1/2 via Gi-dependent mechanism in adipocytes (Gerhardt et al., 1999; Soeder et al., 1999). Unlike β2AR, the β3AR doesn’t require receptor phosphorylation and, instead, recruits c-Src kinases for ERK activation in PKA-independent manner (Cao et al., 2000; Robidoux et al., 2006). In contrast, results from other groups argue that β3AR-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is Gs- and PKA-dependent (Lindquist et al., 2000; Mizuno et al., 1999; Mizuno et al., 2000). β3AR signaling is further complicated by alternative splicing of the gene. Two splice variants, β3a and β3bARs that differ only in their C-termini (Evans et al., 1999), also display differences in their signaling properties. The β3aAR couples only with Gs, probably due to localization in caveolae (Sato et al., 2007), whereas the β3bAR couples with Gs and Gi (Hutchinson et al., 2002). Together, these reports indicate that β3AR may activate different signaling mechanisms in different cell systems (white or brown adipocytes, cell lines or primary cultures). We observed in white adipocyte cell lines that β3AR-mediated IL-6 expression is Gi- and ERK1/2-independent, but instead is up-regulated by p38 MAPK and PKC pathways (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of the proposed signaling pathways for activation of IL-6 gene by β3AR stimulation in white adipocytes.

Next, we found that conventional PKCs (α/βII) and novel PKCs (θ and ε) are activated by CL316243 in adipocytes. Our results are in line with previous work showing that β3AR agonists increase glucose uptake in brown adipocytes via conventional and novel PKCs (Chernogubova et al., 2004). Furthermore, up-regulation of IL-6 in a PKA-independent but PKC- and p38-dependent manner has been previously reported for various G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) in other types of cells, such as P2Y receptors in microglia (Shigemoto-Mogami et al., 2001) and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2β in smooth muscle cells (Kageyama and Suda, 2003) as well as under inflammatory conditions in astrocytes (Norris et al., 1994). Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of PKC activation by β3AR and its relation to p38. As PKCs are known to be downstream effectors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (Standaert et al., 1997), it is plausible that PKCs activated by β3ARs in adipocytes are downstream of PI3K and not directly activated by elevated cAMP. Interestingly, while p38 and PKC pathways appear to be distinct, our findings reveal that inhibition of either one of them can completely abolish IL-6 expression, suggesting an interaction of these two pathways in IL-6 induction, most likely at the level of transcriptional regulation and/or mRNA stability.

The p38 and PKC pathways activate multiple transcription factors including CREB, ATF-1, ATF-2, AP-1, C/EBPβ, and ETS (Buchwalter et al., 2004; Deak et al., 1998; Isakov and Altman, 2002; Kawasaki et al., 1998a; Li et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2005; Morton et al., 2004; Tan et al., 1996; Togo, 2004; Trautwein et al., 1993). Besides, the promoter region of IL-6 gene contains several functional binding sites such as CRE, AP-1, C/EBP, and NF-κB (Ammit et al., 2002; Edwards et al., 2007; Eickelberg et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 1996). Searching for transcription factors activated by β3AR agonist CL316243, we found that β3AR stimulation leads to increased expression of reporter constructs containing CRE, but not AP-1, C/EBP, ETS or NF-κB binding sites, which is in accord with our results from the homogenous reporter assay. Furthermore, significant increases in phosphorylation of CREB, ATF-1, and ATF-2 transcription factors were observed in response to β3AR-agonist treatment. These transcription factors belong to a large ATF/CREB family of the basic region-leucine zipper (bZip) proteins which are defined by their ability to bind to the consensus CRE site (Hai and Hartman, 2001). We next found that pretreatment with a p38 inhibitor remarkably decreased CREB and ATF-2 phosphorylation, and that pretreatment with a PKC inhibitor diminished ATF-2 activation alone. Overwhelming evidence indicates that ATF/CREB proteins form selective homo- and heterodimers (De Cesare and Sassone-Corsi, 2000). Thus, it is plausible that activation of both CREB and ATF-2 transcription factors is required for IL-6 production, and that these two factors may work synergistically to regulate cytokine expression in adipocytes. The exact mechanism of their interaction merits further research. Nevertheless, our results strongly suggest that the CRE site in the IL-6 promoter is the main target for β3AR-induced transcription, and that this gene activation is mediated by the actions of CREB and ATF-2 transcription factors.

Our findings have important clinical implications. Converging lines of evidence have revealed that inflammation is a key feature of obesity and type 2 diabetes (Wellen and Hotamisligil, 2005). Although a causal role of IL-6 in diabetes still needs to be clarified, IL-6 levels correlate with the degree of insulin resistance in human subjects (Bastard et al., 2002; Kern et al., 2001) and predict the development of type 2 diabetes (Hu et al., 2004; Thorand et al., 2007). Additionally, circulating levels of IL-6 are elevated in patients with painful inflammatory and musculoskeletal conditions (Liebregts et al., 2007). Selective β3AR antagonists have been shown to reduce circulating levels of IL-6 and corresponding pain behavior in an animal pain model (Nackley et al., 2005; Nackley et al., 2007). On the other hand, IL-6 plays protective role improving adenosinergic signaling and increasing neuronal survival under various pathological conditions (Biber et al., 2008). Furthermore, experiments with hepatectomy and hepatic warm ischemia/reperfusion injury demonstrated that IL-6 is a critical component for hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration (Camargo et al., 1997; Cressman et al., 1996). In pursuit of novel therapeutic approaches a series of human β3AR agonists and antagonists has recently been generated (Brockunier et al., 2001; Candelore et al., 1999; Mathvink et al., 2000; Parmee et al., 2000). Thus, this work may promote the development of new therapeutic avenues for the treatment of obesity, inflammatory pain conditions, brain pathology, and liver diseases.

5. Conclusions

The present work provides novel insights into signal transduction cascades mediating the β3AR-dependent release of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in adipocytes. Here, we report that this IL-6 increase is Gi-independent and doesn’t rely on ERK1/2, PKA, or NF-κB pathways. Instead, it’s mediated by p38 and PKC signaling through activation of transcription factors CREB and ATF-2. Elucidation of cellular network regulating IL-6 expression improves our understanding of molecular mechanisms in obesity, inflammatory pain, and other pathological conditions where a significant role for IL-6 is implicated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathryn Satterfield for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 DE016558 to L.D. and P01 NS045685 to W.M.

References

- Ammit AJ, Lazaar AL, Irani C, O’Neill GM, Gordon ND, Amrani Y, Penn RB, Panettieri RA., Jr Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced secretion of RANTES and interleukin-6 from human airway smooth muscle cells: modulation by glucocorticoids and beta-agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:465–74. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad M, Aoki VT, Adkison MG, Warren WS, Bartness TJ. Central nervous system origins of the sympathetic nervous system outflow to white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R291–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard JP, Maachi M, Van Nhieu JT, Jardel C, Bruckert E, Grimaldi A, Robert JJ, Capeau J, Hainque B. Adipose tissue IL-6 content correlates with resistance to insulin activation of glucose uptake both in vivo and in vitro. Journal Clinical Endocrinology Metabolism. 2002;87:2084–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber K, Pinto-Duarte A, Wittendorp MC, Dolga AM, Fernandes CC, Von Frijtag Drabbe Kunzel J, Keijser JN, de Vries R, Ijzerman AP, Ribeiro JA, Eisel U, Sebastiao AM, Boddeke HW. Interleukin-6 upregulates neuronal adenosine A1 receptors: implications for neuromodulation and neuroprotection. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2237–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JD, Dutia MD, Johnson BD, Wissner A, Burns MG, Largis EE, Dolan JA, Claus TH. Disodium (R,R)-5-[2-[[2-(3-chlorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl]-amino] propyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-2,2-dicarboxylate (CL 316,243). A potent beta-adrenergic agonist virtually specific for beta 3 receptors. A promising antidiabetic and antiobesity agent. J Med Chem. 1992;35:3081–4. doi: 10.1021/jm00094a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockunier LL, Candelore MR, Cascieri MA, Liu Y, Tota L, Wyvratt MJ, Fisher MH, Weber AE, Parmee ER. Human beta3 adrenergic receptor agonists containing cyanoguanidine and nitroethylenediamine moieties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:379–82. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwalter G, Gross C, Wasylyk B. Ets ternary complex transcription factors. Gene. 2004;324:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burysek L, Houstek J. beta-Adrenergic stimulation of interleukin-1alpha and interleukin-6 expression in mouse brown adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:83–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo CA, Jr, Madden JF, Gao W, Selvan RS, Clavien PA. Interleukin-6 protects liver against warm ischemia/reperfusion injury and promotes hepatocyte proliferation in the rodent. Hepatology. 1997;26:1513–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelore MR, Deng L, Tota L, Guan XM, Amend A, Liu Y, Newbold R, Cascieri MA, Weber AE. Potent and selective human beta(3)-adrenergic receptor antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Luttrell LM, Medvedev AV, Pierce KL, Daniel KW, Dixon TM, Lefkowitz RJ, Collins S. Direct binding of activated c-Src to the beta 3-adrenergic receptor is required for MAP kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38131–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Medvedev AV, Daniel KW, Collins S. beta-Adrenergic activation of p38 MAP kinase in adipocytes: cAMP induction of the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) gene requires p38 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27077–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel D, Selinger Z. Mechanism of adenylate cyclase activation by cholera toxin: inhibition of GTP hydrolysis at the regulatory site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3307–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernogubova E, Cannon B, Bengtsson T. Norepinephrine increases glucose transport in brown adipocytes via beta3-adrenoceptors through a cAMP, PKA, and PI3-kinase-dependent pathway stimulating conventional and novel PKCs. Endocrinology. 2004;145:269–80. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S, Cao W, Robidoux J. Learning new tricks from old dogs: beta-adrenergic receptors teach new lessons on firing up adipose tissue metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2123–31. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressman DE, Greenbaum LE, DeAngelis RA, Ciliberto G, Furth EE, Poli V, Taub R. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:1379–83. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare D, Sassone-Corsi P. Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP-responsive factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2000;64:343–69. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–7. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak M, Clifton AD, Lucocq LM, Alessi DR. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) is directly activated by MAPK and SAPK2/p38, and may mediate activation of CREB. EMBO J. 1998;17:4426–41. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MR, Haas J, Panettieri RA, Jr, Johnson M, Johnston SL. Corticosteroids and beta2 agonists differentially regulate rhinovirus-induced interleukin-6 via distinct Cis-acting elements. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15366–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickelberg O, Pansky A, Mussmann R, Bihl M, Tamm M, Hildebrand P, Perruchoud AP, Roth M. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces interleukin-6 expression via activating protein-1 consisting of JunD homodimers in primary human lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12933–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BA, Papaioannou M, Hamilton S, Summers RJ. Alternative splicing generates two isoforms of the beta3-adrenoceptor which are differentially expressed in mouse tissues. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1525–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2273–82. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenteany G, Standaert RF, Lane WS, Choi S, Corey EJ, Schreiber SL. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science. 1995;268:726–31. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliers E, Kreier F, Voshol PJ, Havekes LM, Sauerwein HP, Kalsbeek A, Buijs RM, Romijn JA. White adipose tissue: getting nervous. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:1005–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:847–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt CC, Gros J, Strosberg AD, Issad T. Stimulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway by human beta-3 adrenergic receptor: new pharmacological profile and mechanism of activation. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:255–62. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornikiewicz A, Sautner T, Brostjan C, Schmierer B, Fugger R, Roth E, Muhlbacher F, Bergmann M. Catecholamines up-regulate lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-6 production in human microvascular endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2000;14:1093–100. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.9.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding EH, Ngai J, Kramer RH, Colicos S, Axel R, Siegelbaum SA, Chess A. Molecular cloning and single-channel properties of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from catfish olfactory neurons. Neuron. 1992;8:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90107-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H, Kehinde O. Spontaneous heritable changes leading to increased adipose conversion in 3T3 cells. Cell. 1976;7:105–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan XM, Amend A, Strader CD. Determination of structural domains for G protein coupling and ligand binding in beta 3-adrenergic receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:492–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T, Hartman MG. The molecular biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription factors: activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis. Gene. 2001;273:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch M, Eberle AN, Peterli R, Peters T, Seboek D, Keller U, Muller B, Linscheid P. LPS induces interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human adipocytes. Cytokine. 2008;41:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB, Meigs JB, Li TY, Rifai N, Manson JE. Inflammatory markers and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes. 2004;53:693–700. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson DS, Bengtsson T, Evans BA, Summers RJ. Mouse beta 3a- and beta 3b-adrenoceptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells display identical pharmacology but utilize distinct signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1903–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakov N, Altman A. Protein kinase C(theta) in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:761–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BD, Kimura K, Kitamura H, Makondo K, Okita K, Kawasaki M, Saito M. Norepinephrine stimulates interleukin-6 mRNA expression in primary cultured rat hepatocytes. J Biochem. 2000;127:205–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama K, Suda T. Urocortin-related peptides increase interleukin-6 output via cyclic adenosine 5’-monophosphate-dependent pathways in A7r5 aortic smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2234–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura D, Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;149:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Song J, Eckner R, Ugai H, Chiu R, Taira K, Shi Y, Jones N, Yokoyama KK. p300 and ATF-2 are components of the DRF complex, which regulates retinoic acid- and E1A-mediated transcription of the c-jun gene in F9 cells. Genes Dev. 1998a;12:233–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998b;282:2275–9. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E745–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6: from basic science to medicine--40 years in immunology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS, Sun TJ, Saxe CL, 3rd, Kimmel AR, Johnson RL, Devreotes PN. A chemoattractant receptor controls development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Science. 1988;241:1467–72. doi: 10.1126/science.3047871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR. Signaling pathways regulating murine cardiac CREB phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, Roth A, Heinzel S, Lester S, Downie-Doyle S, Smith E, Drew P, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:913–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JY, Park SJ, Hwang HY, Park EJ, Nam JH, Kim J, Park SI. TGF-beta1 induces cardiac hypertrophic responses via PKC-dependent ATF-2 activation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:627–36. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist JM, Fredriksson JM, Rehnmark S, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Beta 3-and alpha1-adrenergic Erk1/2 activation is Src- but not Gi-mediated in Brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22670–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909093199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathvink RJ, Tolman JS, Chitty D, Candelore MR, Cascieri MA, Colwell LF, Jr, Deng L, Feeney WP, Forrest MJ, Hom GJ, MacIntyre DE, Miller RR, Stearns RA, Tota L, Wyvratt MJ, Fisher MH, Weber AE. Discovery of a potent, orally bioavailable beta(3) adrenergic receptor agonist, (R)-N-[4-[2-[[2-hydroxy-2-(3-pyridinyl)ethyl]amino]ethyl]phenyl]-4-[4 -[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]thiazol-2-yl]benzenesulfonamide. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3832–6. doi: 10.1021/jm000286i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May MJ, D’Acquisto F, Madge LA, Glockner J, Pober JS, Ghosh S. Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by a peptide that blocks the interaction of NEMO with the IkappaB kinase complex. Science. 2000;289:1550–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Kanda Y, Kuroki Y, Nishio M, Watanabe Y. Stimulation of beta(3)-adrenoceptors causes phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase via a stimulatory G protein-dependent pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:951–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Kanda Y, Kuroki Y, Tomiyama K, Watanabe Y. Phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by stimulation of beta(3)-adrenoceptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;385:63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00733-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Kanda Y, Kuroki Y, Watanabe Y. The stimulation of beta(3)-adrenoceptor causes phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 through a G(s)-but not G(i)-dependent pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;404:63–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed-Ali V, Flower L, Sethi J, Hotamisligil G, Gray R, Humphries SE, York DA, Pinkney J. beta-Adrenergic regulation of IL-6 release from adipose tissue: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5864–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, Katz DR, Miles JM, Yudkin JS, Klein S, Coppack SW. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4196–200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton S, Davis RJ, Cohen P. Signalling pathways involved in multisite phosphorylation of the transcription factor ATF-2. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moule SK, Denton RM. The activation of p38 MAPK by the beta-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in rat epididymal fat cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:287–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung J, Kim KB, Crews CM. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:245–73. doi: 10.1002/med.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Faison JM, Lambeth BL, Diatchenko L, Maixner W. Society for Neuroscience. Washington, D.C.: 2005. Catechol-O-methyltransferase modulates pain behavior and cytokine production via beta2/3-adrenergic receptor mechanisms. [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Tan KS, Fecho K, Flood P, Diatchenko L, Maixner W. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition increases pain sensitivity through activation of both beta2-and beta3-adrenergic receptors. Pain. 2007;128:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris JG, Benveniste EN. Interleukin-6 production by astrocytes: induction by the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;45:137–45. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90174-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris JG, Tang LP, Sparacio SM, Benveniste EN. Signal transduction pathways mediating astrocyte IL-6 induction by IL-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Immunol. 1994;152:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou DA, Petrides JS, Tsigos C, Bina S, Kalogeras KT, Wilder R, Gold PW, Deuster PA, Chrousos GP. Exercise stimulates interleukin-6 secretion: inhibition by glucocorticoids and correlation with catecholamines. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E601–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.3.E601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmee ER, Brockunier LL, He J, Singh SB, Candelore MR, Cascieri MA, Deng L, Liu Y, Tota L, Wyvratt MJ, Fisher MH, Weber AE. Tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives containing a benzenesulfonamide moiety as potent, selective human beta3 adrenergic receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:2283–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Path G, Bornstein SR, Gurniak M, Chrousos GP, Scherbaum WA, Hauner H. Human breast adipocytes express interleukin-6 (IL-6) and its receptor system: increased IL-6 production by beta-adrenergic activation and effects of IL-6 on adipocyte function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2281–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, Tatter SB, May LT, Sehgal PB. Activation of the human “beta 2-interferon/hepatocyte-stimulating factor/interleukin 6” promoter by cytokines, viruses, and second messenger agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6701–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robidoux J, Kumar N, Daniel KW, Moukdar F, Cyr M, Medvedev AV, Collins S. Maximal beta3-adrenergic regulation of lipolysis involves Src and epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37794–802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature. 2002;415:206–12. doi: 10.1038/415206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov S, Medvedev A, Gambarian M, Poltoratskaya N, Moeser M, Medvedeva L, Diatchenko L, Makarov S. Homogeneous reporter system enables quantitative functional assessment of multiple transcription factors. Nat Methods. 2008;5:253–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Hutchinson DS, Evans BA, Summers RJ. Functional domains of the mouse beta(3)-adrenoceptor associated with differential G-protein coupling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1035–7. doi: 10.1042/BST0351035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Tsuda M, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S, Inoue K. Mechanisms underlying extracellular ATP-evoked interleukin-6 release in mouse microglial cell line, MG-5. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1339–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skurk T, Alberti-Huber C, Herder C, Hauner H. Relationship between adipocyte size and adipokine expression and secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1023–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin BG, Ballard KW. Morphological studies on the adrenergic innervation of white adipose tissue. Anat Rec. 1978;191:377–89. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091910310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeder KJ, Snedden SK, Cao W, Della Rocca GJ, Daniel KW, Luttrell LM, Collins S. The beta3-adrenergic receptor activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in adipocytes through a Gi-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12017–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standaert ML, Galloway L, Karnam P, Bandyopadhyay G, Moscat J, Farese RV. Protein kinase C-zeta as a downstream effector of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase during insulin stimulation in rat adipocytes. Potential role in glucose transport. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30075–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki A, Huang QH, Somogyvari-Vigh A, Arimura A. Immobilization stress may increase plasma interleukin-6 via central and peripheral catecholamines. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1994;1:335–42. doi: 10.1159/000097185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KS, Nackley AG, Satterfield K, Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Flood PM. Beta2 adrenergic receptor activation stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages via PKA- and NF-kappaB-independent mechanisms. Cell Signal. 2007;19:251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Rouse J, Zhang A, Cariati S, Cohen P, Comb MJ. FGF and stress regulate CREB and ATF-1 via a pathway involving p38 MAP kinase and MAPKAP kinase-2. EMBO J. 1996;15:4629–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tentolouris N, Liatis S, Katsilambros N. Sympathetic system activity in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:129–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorand B, Baumert J, Kolb H, Meisinger C, Chambless L, Koenig W, Herder C. Sex differences in the prediction of type 2 diabetes by inflammatory markers: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study, 1984-2002. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:854–60. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togo T. Long-term potentiation of wound-induced exocytosis and plasma membrane repair is dependent on cAMP-response element-mediated transcription via a protein kinase C- and p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44996–5003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein C, Caelles C, van der Geer P, Hunter T, Karin M, Chojkier M. Transactivation by NF-IL6/LAP is enhanced by phosphorylation of its activation domain. Nature. 1993;364:544–7. doi: 10.1038/364544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Kales A, Tyson K, Chrousos GP. Elevation of plasma cytokines in disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness: role of sleep disturbance and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1313–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicennati V, Vottero A, Friedman C, Papanicolaou DA. Hormonal regulation of interleukin-6 production in human adipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:905–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson SE, Parker PJ, Nixon JS. Isoenzyme specificity of bisindolylmaleimides, selective inhibitors of protein kinase C. Biochem J. 1993;294(Pt 2):335–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2940335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirsen C, Hamberger B. Catecholamines in brown fat. Nature. 1967;214:625–6. doi: 10.1038/214625a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka S, Courtois G, Bessia C, Whiteside ST, Weil R, Agou F, Kirk HE, Kay RJ, Israel A. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IkappaB kinase complex essential for NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1998;93:1231–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Wang YY, Du JH, Li C, Lu ZZ, Han C, Zhang YY. Noncanonical cAMP pathway and p38 MAPK mediate beta2-adrenergic receptor-induced IL-6 production in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:384–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Bae D, Cantrell D, Nel AE, Rozengurt E. Protein kinase D is a downstream target of protein kinase Ctheta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:444–52. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Kusnecov AW, Shurin MR, DePaoli M, Rabin BS. Exposure to physical and psychological stressors elevates plasma interleukin 6: relationship to the activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2523–30. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Tang W, Ray A, Wu Y, Einarsson O, Landry ML, Gwaltney J, Jr, Elias JA. Rhinovirus stimulation of interleukin-6 in vivo and in vitro. Evidence for nuclear factor kappa B-dependent transcriptional activation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:421–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI118431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmuda-Trzebiatowska E, Manganiello V, Degerman E. Novel mechanisms of the regulation of protein kinase B in adipocytes; implications for protein kinase A, Epac, phosphodiesterases 3 and 4. Cell Signal. 2007;19:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]