Abstract

Purpose

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a nonpathogenic yeast, has previously been used as a vehicle to elicit immune responses to foreign antigens, and tumor-associated antigens, and has been shown to reduce tumorburden in mice. Studies were designed to determine if vaccination of human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-transgenic mice (where CEA is a self-antigen) with a recombinant S. cerevisiae construct expressing human CEA (yeast-CEA) elicits CEA-specific T-cell responses and antitumor activity.

Experimental Design

CEA-transgenic mice were vaccinated with yeast-CEA, and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses were assessed after one and multiple administrations or vaccinations at multiple sites per administration. Antitumor activity was determined by tumor growth and overall survival in both pulmonary metastasis and subcutaneous pancreatic tumor models.

Results

These studies demonstrate that recombinant yeast can break tolerance and that a) yeast-CEA constructs elicit both CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses; b) repeated yeast-CEA administration causes increased antigen-specific T-cell responses after each vaccination; c) vaccination with yeast-CEA at multiple sites induces a greater T-cell response than the same dose given at a single site; d) tumor-bearing mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA show a reduction in tumor burden and increased overall survival compared to mock-treated or control yeast-vaccinated mice in both pulmonary metastasis and subcutaneous pancreatic tumor models.

Conclusions

Vaccination with a heat-killed recombinant yeast expressing the tumor-associated antigen CEA induces CEA-specific immune responses, reduces tumor burden, and extends overall survival in CEA-transgenic mice. These studies thus form the rationale for the incorporation of recombinant yeast-CEA and other recombinant yeast constructs in cancer immunotherapy protocols.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, yeast, CEA, tumor immunity

Introduction

One of the reasons for interest in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a vaccine vehicle is its lack of toxicity. Besides being inherently nonpathogenic, this particular species of yeast can be heat-killed before administration and has been shown to be safe in humans in several clinical trials, with maximum tolerated dose not reached (1–3). Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be easily engineered to express one or more antigens in large quantities, can be propagated and purified rapidly, and is very stable (4). In addition, recombinant yeast has been shown to induce a robust host immune response to nonself-antigens (1, 4–6). These characteristics make S. cerevisiae a potential component for cancer immunotherapy protocols.

It has been shown that S. cerevisiae and other yeast species initiate immune responses by inducing maturation of dendritic cells (DCs). In addition to the expected presentation of yeast-expressed antigen via MHC class II, antigen is delivered to MHC class I pathways by cross-presentation (6–10). Because of this ability to induce robust immune responses, several studies have been conducted using S. cerevisiae as a vaccine vehicle. Studies with recombinant S. cerevisiae expressing several different antigens have shown that vaccination with this construct induces antigen-specific T-cell responses both in vitro and in vivo (7, 11–13).

Recently, recombinant S. cerevisiae constructs expressing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) have been engineered for cancer immunotherapy (1, 4, 7). In tumor prevention studies, vaccination with S. cerevisiae expressing TAAs has been shown to protect against tumor challenge (1, 7). Additionally, tumor therapy studies have shown that when tumor-bearing mice are vaccinated with S. cerevisiae constructs expressing the appropriate point-mutated Ras protein, tumor growth is slowed (11, 14).

Because of recombinant S. cerevisiae’s potential for use in cancer therapy, we sought to determine whether a recombinant S. cerevisiae construct expressing carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) would induce CEA-specific T-cell responses and demonstrate antitumor activity against CEA+ tumors in CEA-transgenic (CEA-Tg) mice. CEA is a human self-TAA expressed on a large percentage of human carcinomas, including carcinomas of the colon, rectum, stomach, breast, and lung. Because of this, it has frequently been used as a target for immunotherapy (15). In these studies, we used a CEA-Tg mouse model where CEA is expressed as a self-antigen in fetal tissues and various parts of the gut (16), more accurately mimicking its expression in humans. CEA-Tg mice have been previously shown to be tolerant to CEA (17). To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted where yeast vehicles are employed to break tolerance in mice transgenic for the TAA found in the vaccine.

These studies show for the first time that a) vaccination of CEA-Tg mice with yeast-CEA constructs induces CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, b) multiple yeast-CEA vaccinations can be given, with an increase in T-cell responses seen after each administration, c) single-site vaccination of tumor-bearing mice with yeast-CEA significantly decreases tumor volume and increases overall survival, and d) vaccinating in multiple injection sites produces greater increases in T-cell responses and greater decreases in tumor volume than single-site vaccination.

Materials and Methods

Mice

These studies used 6- to 8-week-old female mice. A breeding pair of C57BL/6 mice that were homozygous for expression of the human CEA gene, designated CEA-transgenic (CEA-Tg) mice, was generously provided by Dr. John Shively (The Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA). The mice were originally generated by microinjecting a 32.6 kb AatII restriction fragment containing the entire human CEA genomic region into a pronucleus of C57BL/6 zygotes (18). The DNA also contained the regulatory sequences that resulted in tissue-specific expression of CEA protein predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract of the CEA-Tg mice. Homozygosity for CEA expression was tested and verified by screening of progeny mice for CEA expression using PCR analysis on mouse tail DNA (15). All mice were housed and maintained in microisolator cages under specific pathogen-free conditions and in accordance with AAALAC guidelines. All experimental studies were carried out under approval of the Intramural Animal Care and Use Committee.

Yeast constructs

A recombinant S. cerevisiae construct expressing full-length CEA was generated by methods similar to those previously described (14). Control yeast (also termed YVEC for vector-transfected yeast) was constructed as previously described (7) (GlobeImmune, Inc., Louisville, CO), except that a constitutive rather than copper-inducible promoter was employed to drive antigen expression. To express CEA, S. cerevisiae was engineered to express full-length glycosylated CEA protein under the control of the yeast constitutive translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF2) promoter. Yeast high copy 2 µM expression plasmid pGI-100 was used as the backbone vector, as described previously (14). Forward primers 5′-CGGAATTCATGGAGTCTCCCTCGGCCCC-3′ and reverse primer 5′- ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCTAAACTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTATCAGAGCAACCCCAACC-3′ were used to amplify the full-length CEA cDNA and inserted into plasmid pGI-172 to generate plasmid pGI-162, which was individually transfected into W303αS. cerevisiae yeast to create yeast-CEA. Expression of the full-length CEA protein was confirmed by immunoblot analysis of lysates from heat-inactivated yeast-CEA using monoclonal antibodies against human CEA (Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, MA). The results revealed a ~71 kDa polypeptide plus an additional ~130 kDa protein. The 130kDa polypeptide apparently harbors complex N-linked glycosylation and the GPI lipid anchor, while the 70 kDa apparently represents a core glycosylated, non-GPI-anchored polypeptide.

Yeast constructs were produced and heat-killed for these studies as previously described (11). Mice were injected with the indicated number of YU (1 YU = 107 yeast particles) of control yeast or yeast-CEA s.c. in the right flank unless otherwise noted.

Poxvirus constructs

Recombinant vaccinia (rV) and recombinant fowlpox (rF) viruses containing murine B7-1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 genes in combination with human CEA (CEA/TRICOM) have been previously described (19). The rF virus containing the gene for murine GM-CSF (rF-GM-CSF) has also been previously described (20). Therion Biologics (Cambridge, MA) kindly provided all of the orthopoxviruses as part of a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health.

Tumor cells

Murine colon carcinoma MC38 cells (H−2b) expressing human CEA (designated MC38-CEA+) were generated by retroviral transduction with CEA cDNA (21). For cytotoxicity assays, the target tumor cell line EL-4 (H−2b, thymoma) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The murine ductal adenocarcinoma cell line Panc02 was generously provided by Dr. Michael A. Hollingsworth (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha). The parental Panc02 cell line was established through the induction of pancreatic tumors with 3-methylcholanthrene and serial s.c. transplantation in C57BL/6 mice (22). Panc02 cells with stable expression of human CEA (designated Panc02.CEA) were generated by retroviral transduction with human CEA cDNA using methods previously described (21). Panc02.CEA cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A media supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1X nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 300 µg/mL G418 sulfate, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Unless otherwise indicated, all media and their components were purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Herndon, VA).

Lymphocyte proliferation assays

To evaluate T-cell immune responses to CEA, splenic T cells were tested for cell proliferation in response to CEA protein. Splenic cells were dispersed into single-cell suspensions in 10% FCS/RPMI1640, followed by removal of red blood cells. Lymphocytes were then separated by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. Cells at the interface were collected and washed in 10% FCS/RPMI1640; CD4+ cells or CD8+ cells were isolated by negative selection and found to be > 90% pure (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Purified T cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured for 5 days (restimulation) in 96-well flat-bottomed plates with naive syngeneic splenocytes irradiated with 2000 rads as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (5 × 105 cells/well) and with CEA protein in 10% FCS/RPMI1640. T cells and APCs were cultured in media only as a control. 3H-thymidine (1 µCi/well) was added to the wells for the last 24 h and harvested using a Tomtec cell harvester (Wallac Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The incorporated radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Wallac 1205 Betaplate, Wallac, Inc.).

CEA-specific CD8+ T-cell immune response

To evaluate CEA-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, spleens were pooled and dispersed into single-cell suspensions and stimulated with 1 µg/mL of the H−2Db-restricted CEA peptide CEA572–579(GIQNSVSA) (CPC Scientific, San Jose, CA) (23). Six days later, bulk splenocytes were separated by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. For the assay of tumor-killing activity, the recovered lymphocytes and 51Cr-labeled target cells (EL-4, 5 × 103 cells/well) pulsed with the CEA572–579 peptide or vesicular stomatitis virus nucleoprotein VSV-NP52–59 (RGYVYQGL) control peptide (CPC Scientific, San Jose, CA) were incubated for 5 h in 96-well U-bottom plates, and radioactivity in supernatants was measured using a gamma-counter (Corba Autogamma, Packard Instruments, Downers Grove, IL). The percentage of tumor lysis was calculated as follows: % tumor lysis = [(experimental cpm – spontaneous cpm) / (maximum cpm – spontaneous cpm)] × 100.

Tumor therapy studies

For tumor therapy studies involving the MC38-CEA+ cell line, 6-week-old female CEA-Tg mice were injected i.v. in the tail with 1 × 106 MC38-CEA+ cells in a volume of 100 µL. Four days following tumor implantation, mice receiving single-site vaccination were injected s.c. in the right flank with PBS, control yeast, or yeast-CEA at 7-day intervals (as indicated in figure legends). Mice vaccinated in 4 sites were injected s.c. in both inner thighs and above each shoulder blade to target the inguinal, axillary, and subclavicular lymph node beds. For studies involving the Panc02.CEA cell line, mice were injected s.c. on the lower back with 1 × 106 Panc02.CEA cells in a volume of 100 µL. In the first of 2 studies evaluating the anti-tumor efficacy of the yeast-CEA vaccine against Panc02.CEA tumors, mice received s.c. injections of either PBS or 1 yeast unit (YU, defined as 1 × 107 yeast particles) of yeast-CEA in the left inner thigh 7 days after tumor challenge, followed by 6 weekly booster vaccinations (1 YU/vaccination) at the same site. The second study was designed to evaluate escalating doses of yeast-CEA by administering 1 YU per site at 1, 2, 4, or 6 vaccination sites chosen to target bilateral regional lymph node beds, including the axillary, subclavicular, inguinal, and mesenteric lymph nodes. As in the first study, mice received a primary vaccination followed by 6 booster vaccinations. Tumors were measured twice weekly by digital caliper in 2 dimensions, and volumes were calculated as previously described (19). In all experiments, mice were sacrificed when they exhibited signs of respiratory distress and/or appeared moribund or cachectic.

Regulatory T–cell assay

To determine the effects of Yeast-CEA on regulatory T-cells (Tregs), spleens were pooled from untreated CEA transgenic mice or mice that were vaccinated in one site with 1YU every 7 days for 4 weeks. Splenocyte single cell suspensions were prepared in 10% FCS/RPMI1640, and red blood cells were removed, and lymphocytes were isolated on a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. The lymphocytes were collected and washed in 10% FCS/RPMI1460. A mouse regulatory T-cell staining kit (eBioscience, Inc, San Diego, CA) was used to identify cells staining CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ as T regs according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were washed and fluorescence was measured with a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The data was analyzed using Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson).

Memory T cell staining

To investigate if yeast-CEA vaccinated animals develop central memory T cells, spleens from mice vaccinated in one site every 7 days for 4 weeks with 1YU at 1 site were harvested, splenocyte single cell suspensions were prepared, and lymphocytes were collected as above. Lymphocytes were washed in PBS/5%BSA and preincubated with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (2.4G2) mAb (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) on ice for 15 min to block FcRs. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the following antibodies: FITC rat anti-mouse CCR7 (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), PECy5 rat antimouse CD8 (BD Biosciences) or isotype controls. The cells were washed twice with PBS/5%BSA and twice with PBS. The stained lymphocytes were resuspended in PBS and fixed using Cytofix Buffer (BD Biosciences). Cell fluorescence was analyzed and compared with that of the appropriate isotype controls (BD Biosciences) with a FACScan cytometer using Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson).

Serum cytokine analysis

Mice were bled and serum isolated 96 hours after vaccination. A Th1/Th2 and proinflammatory cytokine panel was used for serum cytokine analysis by Linco Diagnostic Services (St. Charles, MO).

Toxicology

Antibody levels to SM, histone, SCL-70 (DNA topoisomerase I), dsDNA, ssDNA, and circulating immune complexes were determined in a qualitative or semiquantitative manner (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using ANOVA, with repeated measures using Statview 4.1 (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA). Results of tests of significance were derived from Student's t test using a 2-tailed distribution, and reported as P values (calculated at 95% confidence intervals). In graphic representations of data, y-axis error bars indicate the SD for each point on the graph. In some cases, the variation is such that the plot symbol obscures the error bars. Evaluation of survival patterns in mice bearing lung metastases was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method and ranked according to the Mantel-Cox log-rank test using Statview 4.1. Evaluation of trend in tumor volumes with multiple vaccination sites was performed by linear least squares analysis.

Results

Vaccination with yeast-CEA induces antigen-specific T-cell responses

Previous studies have shown that recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae constructs can elicit immune and antitumor responses in mice (1, 4, 7, 14). However, to our knowledge no studies have been reported showing these effects where the recombinant antigen is “self” in a transgenic mouse model. Therefore, we sought to determine whether vaccination with yeast-CEA could generate CEA-specific immune responses in CEA-Tg mice. Mice were vaccinated with 0.1 yeast unit (YU, defined as 1 × 107 yeast particles) of control yeast or yeast-CEA injected s.c. on days 0 and 7. Mice were sacrificed 14 days later, spleens were harvested, and CD4+ proliferation and CD8+ cell killing assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 1A, vaccination with control yeast induced minimal proliferation at all concentrations of CEA, while vaccination with yeast-CEA induced significantly higher CD4+ proliferation at all concentrations of CEA. For example, at 50 µg/mL CEA, there was a 6-fold increase in proliferation (P = 0.002); at 25 µg/mL CEA: P = 0.001; at 12.5 µg/mL CEA: P = 0.003. Vaccination with yeast-CEA also induced high levels of CEA-specific CD8+ cell killing (Fig. 1B). CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA showed 30% to 40% lysis of target cells pulsed with CEA peptide (closed circles) and only 5% to 15% lysis of target cells pulsed with the control VSV-NP peptide (open circles; P = 0.01 at an effector:target [E:T] ratio of 100:1). CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated with control yeast lysed < 5% of target cells pulsed with either the CEA or VSV-NP peptides (Fig. 1C). In addition, the T-cells from CEA-Tg mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA could lyse tumor cells expressing CEA (Fig 1C Insert). CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA showed 14% lysis of MC38-CEA+ tumor cells (open bars), while mice injected with PBS (vehicle control) showed only 7% lysis (p=0.01). Taken together, these data demonstrate that vaccination with yeast-CEA can break tolerance and induce CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in CEA-Tg mice, and that this effect is specific to the yeast-CEA construct.

Fig. 1.

Vaccination with yeast-CEA induces antigen-specific T-cell responses. CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated with 0.1 YU control yeast or yeast-CEA on days 0 and 7. On day 21, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and splenocytes were used for assays. A, CD4+ cell proliferation. Purified CD4+ T cells were cultured with irradiated APCs and CEA protein for 5 days. 3H-thymidine (1 µCi/well) was added to the wells for the last 24 h, and proliferation was assayed by measuring incorporated radioactivity. Open squares, control yeast. Closed circles, yeast-CEA. B, CD8+ CTL activity after vaccination with yeast-CEA. Splenocytes were stimulated with CEA572–579 peptide for 6 days before assays. Lymphocytes were incubated for 5 h with 51Cr-labeled target EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA or VSV-NP control peptide. Radioactivity in the supernatant was measured and specific lysis calculated. SD is based on the mean of triplicate wells. Open circles, CTL activity directed against EL-4 cells pulsed with VSV-NP peptide. Closed circles, CTL activity directed against EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA peptide. C, CD8+ CTL activity after vaccination with control yeast. Open squares, CTL activity directed against EL-4 cells pulsed with VSV-NP peptide. Closed squares, CTL activity directed against EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA peptide. C (Insert), CD8+ CTL activity against tumor cells after vaccination with yeast-CEA. Splenocytes were stimulated with CEA572–579 peptide as above. Lymphocytes were incubated for 5 h with 51Cr-labeled target MC38-CEA+ (closed bars), at an E:T ratio of 100:1. As a negative control, splenocytes from mice receiving PBS (vehicle control) were stimulated with CEA peptide as above and CTL activity directed against MC38-CEA+ tumor cells (open bars).

Multiple vaccinations with yeast-CEA continuously increase the immune response

Mice were vaccinated 1, 2, 3, or 4 times at 7-day intervals with 0.1 YU of control yeast or yeast-CEA. Mice were sacrificed 14 days after the last vaccination, spleens were harvested, and splenocytes were used in both CD4+ proliferation and CD8+ cell killing assays. CD4+ cells from mice vaccinated with control yeast showed minimal proliferation in response to CEA protein, irrespective of the number of vaccinations (Fig. 2A). However, in mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA, proliferation of CD4+ cells continued to increase as the number of vaccinations increased (Fig. 2B). There was a 10-fold increase in proliferation after the second vaccination (P = 0.001) and a 1.5-fold increase after the third vaccination (P = 0.006). Although not statistically significant (P = 0.1), there was a further increase in proliferation after the fourth vaccination. A similar trend was seen in CD8+ cell killing assays. CD8+ cells from mice vaccinated with control yeast showed no/minimal killing even after 4 vaccinations (Fig. 2D). In mice given yeast-CEA, an increase in cell lysis was seen after each of the first 2 vaccinations, with a much greater increase in cell lysis after 3 vaccinations (P = 0.01) (Fig. 2E) and a significant increase from the third to the fourth vaccination (P = 0.02) (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these data show that yeast-CEA can be given up to 4 times, with an increase in both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses after each vaccination. To compare the relative potency of vaccination with yeast-CEA with another vaccination platform, mice were first vaccinated with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing CEA and a TRIad of COstimulatory Molecules (rV-CEA-TRICOM) and then boosted weekly for 3 times with a recombinant fowlpox CEA-TRICOM (rF-CEA-TRICOM). Recombinant fowlpox GM-CSF (rF-GM-CSF) was included in this vaccination regimen. Mice vaccinated with CEA-TRICOM showed comparable levels of CEA-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation to mice vaccinated four times with yeast-CEA (Fig. 2C). In addition, mice vaccinated with CEA-TRICOM showed similar levels of CEA-specific CD8+ T-cell responses to mice vaccinated four times with yeast-CEA (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Multiple vaccinations with yeast-CEA continuously increase T-cell response. CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated with 0.1 YU control yeast or yeast-CEA 1, 2, 3, or 4 times at 7-day intervals. Fourteen days after the last vaccination, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and splenocytes were used for assays. For comparison, mice were vaccinated with CEA-TRICOM. Open squares, control yeast; filled circles, yeast-CEA; filled squares, DEA-TRICOM. A, CD4+ T-cell proliferation after vaccination with control yeast. Purified CD4+ T cells were cultured with irradiated APCs and CEA protein for 5 days. 3H-thymidine (1 µCi/well) was added to the wells for the last 24 h, and proliferation was assayed by measuring incorporated radioactivity. B, CD4+ T-cell proliferation after vaccination with yeast-CEA. C, CD4+ T-cell proliferation after vaccination with rV/rF-CEA-TRICOM vaccines. D, CD8+ CTL activity after vaccination with control yeast. Splenocytes were stimulated with CEA peptide for 6 days before assays. Lymphocytes were incubated for 5 h with 51Cr-labeled target EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA or VSV-NP control peptide. Radioactivity in the supernatant was measured and specific lysis calculated. SD is based on the mean of triplicate wells. E, CD8+ CTL activity after vaccination with yeast-CEA. F, CD8+ CTL activity after vaccination with rV/rF-CEA-TRICOM vaccines. Data are presented as % lysis after subtraction of VSV-NP control.

Effects of yeast-CEA on T-cell responses are dose-related

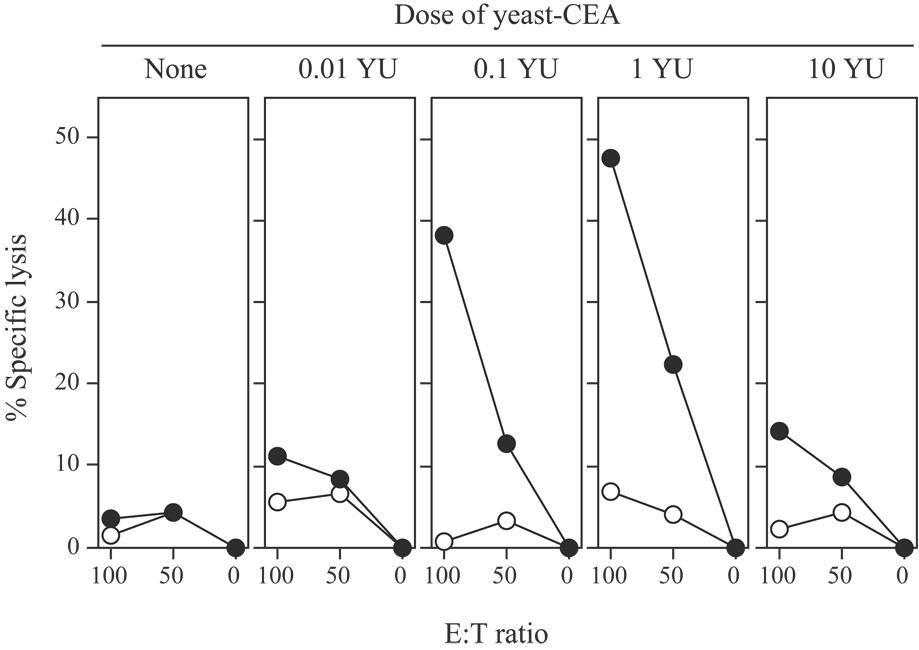

A previous study employing a nonself-antigen has reported a direct correlation between yeast dosage and vaccine efficacy (1). In the experiments described above, 0.1 YU of yeast-CEA effectively induced immune responses. To determine the optimal dose of yeast-CEA in this CEA-Tg model, mice were vaccinated with 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 YU of yeast-CEA on days 0 and 7. Mice were sacrificed 14 days later and spleens were harvested. Splenocytes were incubated with CEA peptide for 6 days before being used in a cell killing assay. As shown in Figure 3, vaccination with 0.01 YU resulted in only a slight increase in CTL killing vs. no treatment. CTL killing increased further with 0.1 YU and 1 YU, with 1 YU showing the highest amount of killing (0.1 YU vs. 0.01 YU: P < 0.001; 1 YU vs. 0.1 YU: P = 0.01). Interestingly, vaccinating mice with 10 YU produced a significant decrease in CTL killing compared to the lower doses of 0.1 or 1 YU (P < 0.001 vs. 1 YU; P = 0.08 vs. no treatment). These data demonstrate that the immune effects of yeast-CEA in this model are dose-related, and that 1 YU is the optimal dose for eliciting antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell killing. In subsequent studies, we therefore used a dosage of 1 YU of yeast-CEA.

Fig. 3.

CD8+ CTL responses after dose escalation of yeast-CEA. CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated with 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 YU yeast-CEA twice at 7-day intervals. Fourteen days after the last vaccination, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and splenocytes were stimulated with CEA peptide for 6 days. Lymphocytes were incubated for 5 h with 51Cr-labeled target EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA or VSV-NP control peptide. Radioactivity in the supernatant was measured and specific lysis calculated. Open circles, EL-4 cells pulsed with VSV-NP peptide. Closed circles, EL-4 cells pulsed with CEA peptide.

To further examine immune responses after vaccination with yeast vectors, studies were conducted on serum cytokines, induction of Tregs, and induction of T-cells with a memory phenotype. First, serum was harvested 96 hours after vaccination with 1YU yeast-CEA or control yeast. Of the ten cytokines analyzed (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, TNF-α, and IL-13), only levels of IL-1β (PTREND =0.029) and IL-6 (p=0.0003) increased while levels of IL-10 decreased (PTREND =0.043) in the serum of mice treated with either yeast-CEA or control yeast as compared to the serum of untreated mice (data not shown). Next, studies were conducted to examine the effect of yeast-CEA on the level of regulatory T-cells. CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated three times with yeast-CEA and after CD4+/FoxP3+ cells were quantitated from splenocytes 14 days after the last vaccination. Mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA showed 0.57% of the CD4+ T-cell population were FoxP3+, while mice that received PBS (vehicle control) showed 0.46% of the CD4+ T-cell population were FoxP3+. This suggests that vaccination with yeast-CEA does not mediate a exaggerated induction of Tregs in CEA-Tg mice. Finally, the phenotype of CD8+ T-cells was examined for surface markers associated with memory T-cells. CEA-Tg mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA showed 0.76% of the whole spleen population stained CD8+/CCR7+, while mice receiving PBS showed 0.67% of the whole spleen population stained CD8+/CCR7+.

Vaccination with yeast-CEA decreases tumor growth and increases survival in tumor-bearing mice

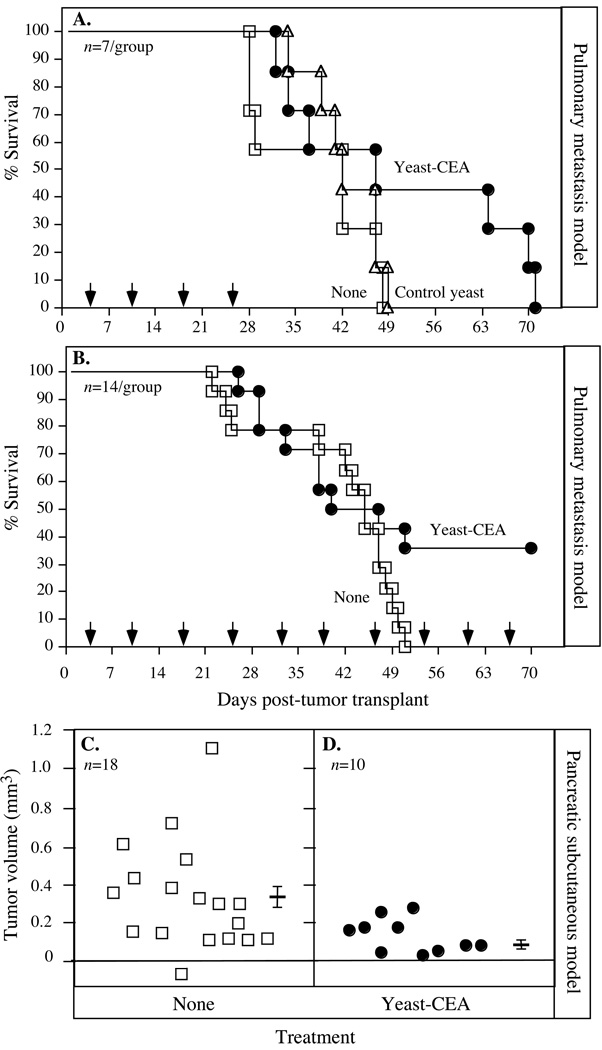

Because the studies described above showed that vaccinating CEA-Tg mice with yeast-CEA induced both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, studies were then conducted to determine whether these effects would translate to antitumor efficacy. We analyzed yeast-CEA vaccination in 2 different CEA+ tumor therapy models. In the first, an experimental pulmonary metastasis model, mice were injected with 1 × 106 MC38-CEA+ cells i.v. in the tail. Four days post tumor-transplant, mice (n = 7/group) were treated with 1 YU control yeast or yeast-CEA weekly for a total of 4 vaccinations, and their survival was observed and recorded (Fig. 4A). Mice receiving no treatment (open squares) and mice vaccinated with control yeast (open triangles) all died by day 49 post-tumor transplant. However, mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA (closed circles) survived 63 days post-tumor transplant. As there were only 7 mice per group, this difference was not significant (P = 0.186 vs. mice receiving no treatment or control yeast), but the trend suggested that vaccination with yeast-CEA increased survival. To extend these findings in the same model (Fig. 4B), the number of mice per group was increased to 14 and mice were now vaccinated weekly for the duration of the experiment. Mice receiving no treatment all died by day 50 (Fig. 4B), as in the previous experiment (Fig. 4A). However, by day 70, 35% of mice receiving yeast-CEA were still alive. This effect on survival was significant compared to the no treatment group (P = 0.039). These data show that vaccination with yeast-CEA significantly extends survival in a CEA+ experimental pulmonary metastasis model, when continued to be administered weekly.

Fig. 4.

Vaccination with yeast-CEA reduces tumor growth and increases overall survival in tumor-bearing mice. A, survival in an experimental CEA+ lung metastasis model. CEA-Tg mice (n = 7/group) were injected with 1 × 106 MC38-CEA+ tumor cells i.v. in the tail on day 0, and mock-treated or injected with 1 YU control yeast or yeast-CEA s.c. on days 4, 11, 18, and 25 (arrows). Mice were monitored and survival was recorded. Open squares, no treatment. Open triangles, control yeast. Closed circles, yeast-CEA. B, Survival in a lung metastasis model with continuous weekly vaccination (arrows). CEA-Tg mice (n = 14/group) were injected with 1 × 106 MC38-CEA+ tumor cells i.v. in the tail on day 0, and were mock-treated or injected with 1 YU yeast-CEA s.c. starting on day 4, then weekly for the duration of the experiment. Mice were monitored and survival was recorded. Open squares, no treatment. Closed circles, yeast-CEA. C–D, Vaccination with yeast-CEA in a s.c. pancreatic cancer model. CEA-Tg mice were injected with 1 × 106 Panc02.CEA cells s.c. on day 0, and vaccinated with 1 YU yeast-CEA starting on day 7, then weekly for the duration of the experiment. Tumor volume was measured twice a week and recorded. C, no treatment (n = 18). D, yeast-CEA (n = 10). Bar indicates average tumor volume ± SD.

We next conducted experiments using a murine pancreatic cancer cell line transfected with the CEA gene, as described in Materials and Methods. 1 × 106 Panc02.CEA cells were implanted s.c. into CEA-Tg mice on day 0. Mice were vaccinated on day 7 post-tumor transplant and were vaccinated weekly with yeast-CEA for the duration of the experiment; tumor volumes were measured. For mice receiving no treatment (Fig. 4C), average tumor volume at day 35 post-tumor transplant was 0.32 mm3; for mice receiving yeast-CEA (Fig. 4D), average tumor size at the same time point was significantly smaller (0.13 mm3; P = 0.03). Reduced tumor volume in this model also correlated with increased survival, as mice receiving yeast-CEA survived significantly longer than those receiving no treatment (P = 0.0008). Taken together (Figs. 4A to 4D), these data demonstrate that vaccination with yeast-CEA slows tumor growth and extends survival in CEA-Tg tumor-bearing mice.

Multiple-site vaccination is more effective than single-site vaccination

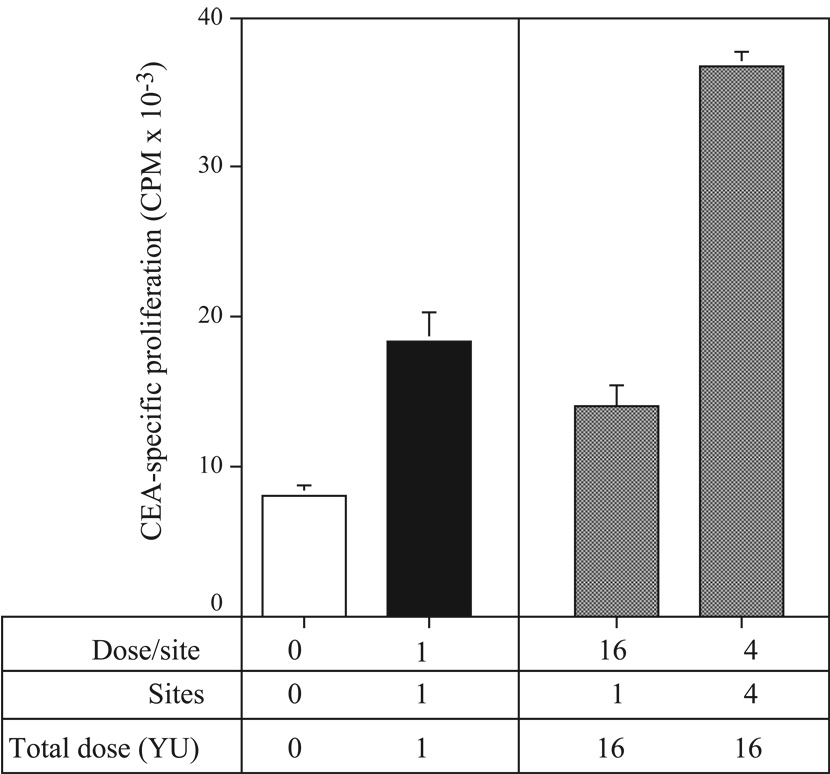

In the experiments described above, mice were vaccinated in a single site. However, previous studies using whole tumor-cell vaccines have suggested that vaccinating in multiple sites, thereby targeting multiple draining lymph nodes, could induce a more effective immune response (24, 25). Mice vaccinated on days 0 and 7 in 4 sites received vaccine s.c. in both inner thighs and above each shoulder blade in order to target the inguinal, axillary, and subclavicular lymph node beds. Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and splenocytes were analyzed in a CEA-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation assay. Mice injected with 1 YU in a single site (as in previous studies described above) showed a significant increase in CD4+ T-cell proliferation vs. mice receiving no treatment (Fig. 5, left panel; P = 0.001). CD4+ T-cell proliferation was then tested in mice vaccinated with 16 total YU (Fig. 5, right panel), either in a single site (left bar) or distributed over 4 sites, with 4 YU/site (right bar). CD4+ T-cell proliferation increased significantly in mice vaccinated with 16 YU distributed over multiple sites, compared to mice receiving either 1 YU (P = 0.0001) or 16 YU (P < 0.0001) in a single site. These data demonstrate that, while vaccinating in a single site effectively induces CD4+ T-cell responses, spreading the same dose out over multiple sites improves the magnitude of this response.

Fig. 5.

CD4+ T-cell responses increase when vaccine is distributed to multiple sites. CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated with a total of 1 or 16 YU yeast-CEA s.c. in 1 or 4 sites on days 0 and 7. Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and CD4+ T cells were purified. Cells were cultured with irradiated APCs and CEA protein for 5 days. 3H-thymidine (1 µCi/well) was added to the wells for the last 24 h, and proliferation was assayed by measuring incorporated radioactivity. SD is based on the mean of triplicate wells. Open bar, no treatment. Black bar, 1 YU in 1 site. Gray bars, 16 total YU.

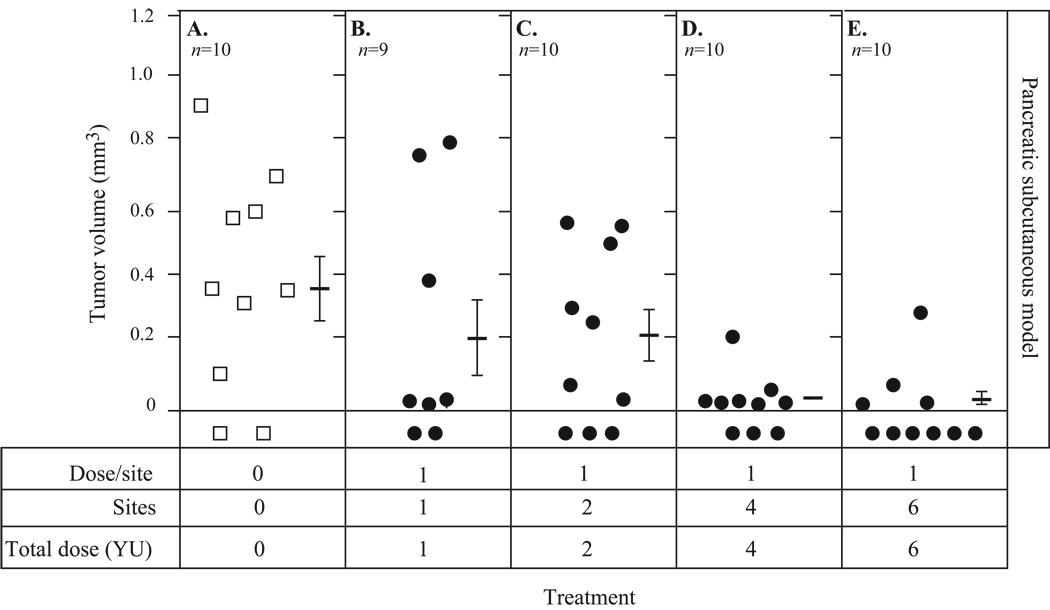

With this knowledge at hand, studies were conducted to determine whether vaccinating in multiple sites would further increase antitumor efficacy. Mice were implanted with Panc02.CEA cells s.c. on day 0 and vaccinated weekly beginning 7 days post-tumor transplant with 1 YU of yeast-CEA in each of 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 sites for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 6). Average tumor volumes on day 32 post-tumor transplant were recorded as follows: 0.38 mm3 for mice receiving no treatment (Fig. 6A); 0.22 mm3 for mice vaccinated in a single site (Fig. 6B); and 0.23 mm3 for mice vaccinated in 2 sites (Fig. 6C). Tumor volume decreased further as the number of vaccination sites increased. Average tumor volume for mice vaccinated in 4 sites (Fig. 6D) was 0.035 mm3, and 0.042 mm3 for mice vaccinated in 6 sites (Fig. 6E). The number of vaccination sites also correlated with the number of tumor-free mice and with survival, as mice receiving vaccine in 4 or 6 sites survived longer than those receiving vaccine in 0, 1, or 2 sites (P = 0.04). At day 80 post-tumor transplant, 70% of mice vaccinated at 4 to 6 sites (n = 20) were alive, compared to 55% of mice vaccinated at 1 to 2 sites (n = 20) and 40% of control mice (n = 20). Collectively (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6), these data indicate that multiple-site vaccination induces more potent immune response and antitumor efficacy than single-site vaccination.

Fig. 6.

Vaccination in multiple sites increases antitumor efficacy. CEA-Tg mice were implanted with 1 × 106 Panc02.CEA cells s.c. on day 0 and vaccinated in 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 sites with 1 YU yeast-CEA/site starting on day 7, then weekly for the duration of the experiment. Tumor volume was measured twice a week and recorded. A, no treatment (n = 10). B, 1YU in 1 site (n = 9). C, 1 YU in 2 sites (n = 10). D, 1 YU in 4 sites (n = 10). E, 1 YU in 6 sites (n = 10). Bars indicate average tumor volume ± SD. Open squares, no treatment. Closed circles, yeast-CEA.

Vaccination with yeast-CEA does not induce toxicity or autoimmunity

Before the yeast-CEA construct can be used in clinical trials, it must be tested for potential toxicities and autoimmune reactions in an appropriate preclinical model. To this end (Table 1), we vaccinated CEA-Tg mice a total of 4 times in 7-day intervals with 1 YU of yeast-CEA in each of 4 sites (4 YU total). Eight weeks after the final vaccination, no difference was observed in the average weight of mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA and age-matched control mice receiving no treatment (Table 1). No abnormal clinical signs associated with yeast-CEA vaccination were seen in mice throughout the observation period. Two weeks after the final vaccination, blood was drawn from the mice, pooled, and a complete blood count (CBC) was performed. All results were within normal limits, with no significant differences between vaccinated and nonvaccinated mice (Table 1). To further examine toxicity, sera were collected from mice 3 weeks after the final vaccination and 8 serological parameters were measured. As with the CBC, all results were within normal limits, with no significant differences between vaccinated and nonvaccinated mice (Table 1). Because these studies were conducted in CEA-Tg mice, there was a possibility that vaccination with yeast-CEA would induce autoimmunity. To test this, we examined sera samples for levels of antinuclear antibodies specific for nRNP, histone, topoisomerase-1 (scl-70), dsDNA, ssDNA, or circulating immune complexes. There were no detectable levels of antibody in sera samples from mice receiving yeast-CEA or from age-matched control mice (Table 1). Histone and CIC levels were similar in both vaccinated and control groups (+/− Table 1); it should be noted, however, that these levels were only slightly above the lower detection limits of the assays and that normal naive C57BL/6 mice have been shown to experience spontaneous age-related increases in antinuclear antibodies such as histone and CIC. Thus, although CEA-Tg mice receiving yeast-CEA mounted a therapeutic immune response (Fig. 5 and Fig 6), they showed no evidence of autoimmunity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, blood, serological, and autoimmune parameters of CEA-Tg mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA

| Test |

aVaccinated Yeast-CEA (n=5) |

bAge-Matched Control Group (n=5) |

|---|---|---|

| bWeight | 24.39g ± 1.46g | 23.45g ± 2.59g |

| cBlood Assays (9) | ||

| WBC count (k/µL) | 9.8 | 10 |

| RBC count (M/µL) | 8.4 | 8.95 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 | 13.5 |

| Mean corpuscular volume; MCV (fl) | 45.2 | 45.2 |

| Platelets (k/µL) | 1075 | 1083 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 84.1 | 87.3 |

| Monocytes (%) | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Basophils (%) | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| dSerum Assays (8) | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen; BUN (mg/dL) | 17 | 15 |

| Creatine kinase (u/L) | 949 | 889 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Alanine aminotransferase; ALT (iu/L) | 32 | 37 |

| Alkaline phosphatase; ALP (iu/L) | 105 | 107 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase; AST (iu/L) | 104 | 131 |

| eAutoimmune Assays (6) | ||

| Smith antigen; Sm Ab | Negative | Negative |

| Histone Ab | +/− | +/− |

| DNA topoisomerase; Scl-70 Ab | Negative | Negative |

| Double-stranded DNA; dsDNA Ab | Negative | Negative |

| Single-stranded DNA; ssDNA Ab | Negative | Negative |

| Circulating iimmune complex; CIC | +/− | +/− |

Twelve-week-old CEA-Tg mice were vaccinated with 1 YU/site over 4 sites (4YU total). Mice were boosted 3 times at 7-day intervals. Age matched mice were CEA-Tg.

Weights were taken 8 weeks following the final boost vaccination.

Blood was drawn 2 weeks following the final boost vaccination and pooled prior to testing.

Sera were drawn 3 weeks following the final boost vaccination and pooled prior to testing.

Results are semiquantitative and are expressed as +/− or 0 to 4+.

Discussion

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a nonpathogenic yeast, has recently gained interest as a vaccine vehicle for the treatment of cancer and infectious diseases. The construct is safe, as the yeast is heat-killed before administration. It can be easily engineered to express antigens in large quantities and can be cultured rapidly. In addition, S. cerevisiae can induce a robust host immune response, delivering antigen to both MHC class I and class II pathways by cross-priming (1, 4–6, 26). All of these qualities make S. cerevisiae an attractive vehicle for cancer immunotherapy. In this study, we sought to determine for the first time whether vaccination with a yeast construct expressing a TAA could break tolerance and induce antigen-specific T-cell and antitumor responses. The data presented here show that vaccination with yeast-CEA not only elicits CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, but also decreases tumor volume and increases overall survival in tumor-bearing mice. For comparison, CEA-Tg mice were also vaccinated with a well-defined CEA-based vaccine, which utilizes poxviruses as delivery vehicles for tumor-associated antigens in combination with TRIad of T cell COstimulatory Molecules (designated TRICOM; B7-1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3) (19). Similar to yeast vaccines, TRICOM-based vaccines have been shown to elicit antigen-specific immune responses by enhancing the ability of DCs to activate both naïve and effector T cells in vitro and in vivo. Vaccination with CEA-TRICOM resulted in similar levels of CD4+ proliferation (Fig. 2C) compared to that seen in mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA (Fig. 2B). In addition, the level of CD8+-specific lysis induced following vaccination with CEA-TRICOM (Fig. 2F) was equivalent to that seen with yeast-CEA injection (Fig. 2E). This observation is similar to that reported in CEA-Tg mice by Bernstein et al (26). Taken together, these data show that vaccination with yeast-CEA elicits CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ immune responses in a “self” antigen system in vivo.

It has been shown that yeast species such as S. cerevisiae initiate immune responses by inducing maturation of DCs (6–10, 26). In this process, the yeast is phagocytized by immature DCs and their proteins are degraded into peptides and presented on the cell surface via MHC class I and class II receptors. The DCs mature and migrate to lymphoid organs, where they prime T-cell responses to yeast antigens (1, 7, 27). Studies with recombinant S. cerevisiae expressing the HIV-1 Gag protein showed that when blood myeloid DCs were exposed to the recombinant yeast, the DCs stimulated the expansion of Gag-specific CD8+ memory T cells in vitro (12). In a separate study, CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated with a yeast construct expressing a hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-core fusion protein killed target cells expressing HCV NS3 (11). Additionally, CTLs from mice vaccinated with recombinant S. cerevisiae expressing the HIV-1SF2-gp160 envelope protein (13) killed target cells expressing gp160-SF2. HIV-1-gp120-specific helper T cells were also induced after vaccination, demonstrating that yeast vehicles can deliver antigens to both MHC class I and class II pathways (7). The study reported here extends these data, as vaccination with yeast-CEA elicited robust antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 5) and CD8+ T-cell lysis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3) of target cells—results made even more significant by the demonstrated breaking of immune tolerance to a self-antigen. These T-cell responses were functionally significant, as evidenced by therapeutic control of tumor proliferation and improved survival in these CEA-Tg mice.

Since therapeutic control of pre-existing cancers is likely to require repeated administration of yeast-CEA to effectively activate tumor-specific immune responses, especially to self-antigens, we explored whether host immune responses to the first yeast-CEA vaccination would decrease or neutralize the efficacy of further boosts. Lu et al. previously reported that vaccinating 10 times with an S. cerevisiae construct expressing Ras demonstrated increased antitumor efficacy over that seen when 6 vaccinations were used (55% vs. 28% reduction in tumor volume, respectively) (28). Additionally, splenocytes from mice vaccinated up to 3 times with a yeast construct expressing an HCV NS3-core fusion protein demonstrated cell killing that increased after each vaccination (11). To our knowledge, however, no one has studied the effect of multiple vaccinations on the induction of T-cell responses in a transgenic mouse model. The studies reported here demonstrate that CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses increase after each of 4 vaccinations (Fig. 2), extending the previous observations suggesting that neutralization of the yeast construct by potential immune responses would not reduce the effectiveness of continued administrations.

Recently, several studies have examined the effect of recombinant S. cerevisiae vehicles expressing TAAs in tumor-bearing mice in non-self systems (1, 4, 7). In several prevention studies, mice vaccinated with a yeast construct expressing a TAA were protected against tumor challenge, while mock-treated mice developed tumor (1, 7). In a spontaneous lung carcinoma model, tumor volume was reduced 28% to 55% in mice vaccinated with yeast constructs expressing mutated Ras (14). These data, taken together, demonstrate that S. cerevisiae constructs can be used for antigen-specific tumor therapy as well as tumor prevention.

An interesting study by Bos et al. describes a potential mechanism for tolerance in the CEA-Tg mouse. In this study, they suggest that expression of CEA on medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTEC) of CEA-Tg mice is involved in restricting CEA-specific CD4+ T cells (29). While they found that CD4+ T cells were essential for tumor eradication in mice vaccinated with a poxvirus expressing CEA, our previous studies show that both CD4 and CD8 cells have a role in antitumor immunity in MC38-CEA tumors in CEA-Tg mice (30). These observations are notable in that the yeast-CEA vaccine used here induces both CD4 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 5) and CD8 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3) responses in CEA-Tg mice and mediates antitumor activity (Fig. 4, Fig. 6), thus providing further evidence that tolerance was broken in this system.

We examined here antitumor efficacy in 2 different tumor models where CEA is a self-antigen. The first was a lung metastasis model where colon carcinoma cells were given i.v. in the tail, forming lung metastases. In this model, mice receiving yeast-CEA had a distinct survival advantage over mice receiving no treatment or control yeast (Fig. 4A). When the number of mice per group was increased and vaccinations were given weekly for the duration of the experiment, survival in yeast-CEA-vaccinated mice was statistically significantly extended compared to mice receiving no treatment (Fig. 4B). To further evaluate antitumor efficacy, we utilized an s.c. CEA+ pancreatic tumor model to measure tumor volume; mice vaccinated with yeast-CEA had a significantly lower tumor volume at day 35 post-tumor transplant than mice receiving no treatment (Fig. 4C), confirming the antitumor effect of vaccination with yeast-CEA seen in the lung metastasis model. Reduced tumor volume in this model also correlated with increased survival (data not shown).

Here it was observed that there was a bell shaped response curve associated with the dose of yeast-CEA with the optimal dose for induction of T-cell responses (Figure 3). This dose relationship has also been observed in another preclinical model targeting a self-tumor antigen (28). There, Lu et al. examined recombinant Yeast delivering rat EGFR as the tumor antigen as an intranasal vaccine for intracranial rat glioma. Three dose levels of Yeast-EGFR were examined; 0.7 YU, 4 YU, and 8 YU. It was observed that all dose levels improved survival over that of PBS treatment; the most striking survival benefit was seen at the 0.7 YU dose (45 days over 28 days for PBS), while rats administered 4 YU and 8 YU had a survival of 42 and 38 days, respectively. It is not clear why there is an optimal dose level for induction of immune responses in the observations of Lu, et al., and our own studies here (Figure 2 and Figure 5), although one could hypothesize that in a self-antigen system T-cells might be more susceptible to antigen induced T-cell anergy. Future studies will examine this possibility.

Data from previous studies employing other types of vaccine vehicles suggest that vaccination at the sites of multiple draining lymph nodes elicits a more effective antitumor response than vaccination at a single site (24, 25). In one study, mice were vaccinated with a whole tumor cell vaccine expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor prior to challenge with a squamous cell carcinoma cell line. Three of 9 mice vaccinated in multiple sites developed tumors by day 15 post-tumor challenge, while 4 of 5 mice receiving a single-site vaccination developed tumors (25). One hypothesis for this effect is that a greater number of precursor T cells are exposed to antigen when mice are vaccinated in multiple sites than when they are vaccinated in a single site, resulting in a subsequent increase in antigen-specific effector T cells (31). Data presented here further suggest that there is a maximum effective dose of yeast-CEA that can be given at one site, as CD8+ T-cell lysis was significantly decreased in mice vaccinated with 10 YU vs. mice vaccinated with 1 YU (Fig. 3). Because of this, we conducted immune and antitumor experiments comparing vaccination in 4 sites vs. a single site, targeting the inguinal, subclavicular, and axial lymph node beds. Our data show that vaccination in 4 sites induces a greater antigen-specific T-cell response than the same total dose given in a single site (Fig. 5). Vaccination in multiple sites had the same effect in tumor-bearing CEA-Tg mice, as vaccination in 4 or 6 sites resulted in lower tumor volume than vaccination in a single site (Fig. 6).

In several clinical trials, recombinant S. cerevisiae vehicles have been found to be safe in both cancer and infectious disease settings. In a phase Ib trial, a yeast construct expressing the HCV NS3-core fusion protein was administered to patients with chronic HCV. Interim analysis from this trial suggests that the yeast construct is safe for use in humans, as no therapy-related SAEs or dose-limiting toxicities have been reported (2). Additionally, at the time of the report, 12 of 29 patients (41%) had generated cellular immune responses to HCV (2). In a cancer setting, a phase I clinical trial with an S. cerevisiae construct expressing mutated Ras was conducted in patients with Ras+ cancers. Again, no treatment-related SAEs were observed, indicating a platform-wide safety profile for administration of heat-killed recombinant yeast to treat chronic diseases. In addition, 19 of 21 vaccinated patients showed > 2-fold antigen-specific responses (3). As a result, a placebo-controlled adjuvant phase II trial in patients with mutated Ras+ fully resected pancreatic cancer is underway.

The transgenic mice used in this study have been shown to overexpress CEA in many fetal tissues and in various parts of the gut, including the stomach, small intestine, cecum, and colon (16). Because CEA has a similar expression pattern in transgenic mice and in humans, these mice are a useful model for studying potential autoimmune phenomena. We performed 24 tests on age-matched mice receiving either no treatment or yeast-CEA. For the vaccinated mice, weight, CBC, serum enzyme levels, and autoimmune assays were all within the normal range and were similar to the age-matched controls, indicating no toxicity or autoimmunity related to yeast-CEA (Table 1). These data thus have implications for potential use of the yeast-CEA vehicle in humans. A potential translational path to test these findings would be to vaccinate patients who have CEA-positive carcinomas with Yeast-CEA and measure CEA-specific immune responses. Based on the findings presented here, the patients could be vaccinated in multiple sites, targeting different lymph node beds to maximize the immune response to the Yeast-CEA vector. We could envision future studies that would focus on patients with CEA-positive non-small cell lung carcinoma. Patients could receive Yeast-CEA in combination with standard of care chemotherapy, and CEA-specific immune responses as well as time to progression could be monitored.

The data reported here demonstrate that vaccination with yeast-CEA can break tolerance and induce CEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, effectively reduces tumor burden, and extends overall survival in tumor-bearing mice without adverse effects. These results thus form the rationale for the potential use of yeast-CEA in immunotherapy protocols for carcinoma patients with CEA+ tumors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Marion Taylor and the editorial assistance of Bonnie L. Casey and Debra Weingarten in the preparation of this manuscript. We thank Dr. Yingnian Lu, Dr. Tom King, Dr. Deb Quick, Carol Walker, and Aline Oliver of GlobeImmune for their contributions to the characterization, process development, and assay development work for engineering and manufacturing yeast-CEA and control yeast.

Grant support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Franzusoff A, Duke RC, King TH, Lu Y, Rodell TC. Yeasts encoding tumour antigens in cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:565–575. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everson G, et al. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Boston, MA: 2006. Interim results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase Ib study in subjects with chronic HCV after treatment with GI-5005, a yeast-based HCV immunotherapy targeting NS3 and core proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiting SH, Cohn A, Morse MA, O'Neil SB, Bellgrau D, Duke RC, Franzusoff AJ, Munson S, Parker J, Ferraro J, Rodell TC. Treatment of Ras mutation-bearing solid tumor using whole recombinant S. cerevisiae yeast expressing mutated Ras: preliminary safety and immunogenicity results from a Phase I trial; ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; San Francisco, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stubbs AC, Wilson CC. Recombinant yeast as a vaccine vector for the induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2002;4:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heintel T, Breinig F, Schmitt MJ, Meyerhans A. Extensive MHC class I-restricted CD8 T lymphocyte responses against various yeast genera in humans. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:279–286. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buentke E, Scheynius A. Dendritic cells and fungi. Apmis. 2003;111:789–796. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.11107810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubbs AC, Martin KS, Coeshott C, et al. Whole recombinant yeast vaccine activates dendritic cells and elicits protective cell-mediated immunity. Nat Med. 2001;7:625–629. doi: 10.1038/87974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman SL, Holly A. Candida albicans is phagocytosed, killed, and processed for antigen presentation by human dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6813–6822. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6813-6822.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buentke E, Heffler LC, Wallin RP, et al. The allergenic yeast Malassezia furfur induces maturation of human dendritic cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1583–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauman SK, Nichols KL, Murphy JW. Dendritic cells in the induction of protective and nonprotective anticryptococcal cell-mediated immune responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:158–167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haller AA, Lauer GM, King TH, et al. Whole recombinant yeast-based immunotherapy induces potent T cell responses targeting HCV NS3 and Core proteins. Vaccine. 2007;25:1452–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron MA, Blyveis N, Pan SC, Wilson CC. Human dendritic cell interactions with whole recombinant yeast: implications for HIV-1 vaccine development. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:251–264. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzusoff A, Volpe AM, Josse D, Pichuantes S, Wolf JR. Biochemical and genetic definition of the cellular protease required for HIV-1 gp160 processing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3154–3159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y, Bellgrau D, Dwyer-Nield LD, et al. Mutation-selective tumor remission with Ras-targeted, whole yeast-based immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5084–5088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitz J, Reali E, Hodge JW, et al. Identification of an interferon-gamma-inducible carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) CD8(+) T-cell epitope, which mediates tumor killing in CEA transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5058–5064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eades-Perner AM, van der Putten H, Hirth A, et al. Mice transgenic for the human carcinoembryonic antigen gene maintain its spatiotemporal expression pattern. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4169–4176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kass E, Schlom J, Thompson J, et al. Induction of protective host immunity to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a self-antigen in CEA transgenic mice, by immunizing with a recombinant vaccinia-CEA virus. Cancer Res. 1999;59:676–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke P, Mann J, Simpson JF, Rickard-Dickson K, Primus FJ. Mice transgenic for human carcinoembryonic antigen as a model for immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1469–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodge JW, Sabzevari H, Yafal AG, et al. A triad of costimulatory molecules synergize to amplify T-cell activation. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5800–5807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kass E, Parker J, Schlom J, Greiner JW. Comparative studies of the effects of recombinant GM-CSF and GM-CSF administered via a poxvirus to enhance the concentration of antigen- presenting cells in regional lymph nodes. Cytokine. 2000;12:960–971. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins PF, Kantor JA, Salgaller M, et al. Transduction and expression of the human carcinoembryonic antigen gene in a murine colon carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3657–3662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbett TH, Roberts BJ, Leopold WR, et al. Induction and chemotherapeutic response of two transplantable ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1984;44:717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mennuni C, Calvaruso F, Facciabene A, et al. Efficient induction of T-cell responses to carcinoembryonic antigen by a heterologous prime-boost regimen using DNA and adenovirus vectors carrying a codon usage optimized cDNA. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:444–455. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson RC, Pardoll DM, Jaffee EM, et al. Systemic and local paracrine cytokine therapies using transduced tumor cells are synergistic in treating intracranial tumors. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:405–413. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couch M, Saunders JK, O'Malley BW, Jr, Pardoll D, Jaffee E. Spatial distribution of tumor vaccine improves efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1401–1405. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200308000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein MB, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast-CEA) as a potent activator of murine dendritic cells. Vaccine. 2008;26:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Bellgrau D, Rodell TC, Cruickshank S, Franzusoff A. Yeast-based immunotherapy and the threshold of EGFR expression for immune recognition against glioma ovesexpressing self-antigen. American Association for Cancer Research Annual Proceedings. 2006 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos R, van Duikeren S, van Hall T, et al. Expression of a natural tumor antigen by thymic epithelial cells impairs the tumor-protective CD4+ T-cell repertoire. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6443–6449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodge JW, Grosenbach DW, Aarts WM, Poole DJ, Schlom J. Vaccine therapy of established tumors in the absence of autoimmunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1837–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzinger P. Immunology. Memories are made of this? Nature. 1994;369:605–606. doi: 10.1038/369605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]