Abstract

This study elucidates the structure of the anal sphincter complex (ASC) and correlates the individual layers, namely the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS), with their ultrasonographic images. Eighteen male cadavers, with an average age of 72 years (range 62–82 years), were used in this study. Multiple methods were used including gross dissection, coronal and axial sheet plastination, different histological staining techniques and endoanal sonography. The EAS was a continuous layer but with different relations, an upper part (corresponding to the deep and superficial parts in the traditional description) and a lower (subcutaneous) part that was located distal to the IAS, and was the only muscle encircling the anal orifice below the IAS. The CLM was a fibro-fatty-muscular layer occupying the intersphincteric space and was continuous superiorly with the longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum. In its middle and lower parts it consisted of collagen and elastic fibres with fatty tissue filling the spaces between the fibrous septa. The IAS was a markedly thickened extension of the terminal circular smooth muscle layer of the rectum and it terminated proximal to the lower part of the EAS. On endoanal sonography, the EAS appeared as an irregular hyperechoic band; CLM was poorly represented by a thin irregular hyperechoic line and IAS was represented by a hypoechoic band. Data on the measurements of the thickness of the ASC layers are presented and vary between dissection and sonographic imaging. The layers of the ASC were precisely identified in situ, in sections, in isolated dissected specimens and the same structures were correlated with their sonographic appearance. The results of the measurements of ASC components in this study on male cadavers were variable, suggesting that these should be used with caution in diagnostic and management settings.

Keywords: anal canal, correlation with sonography, gross anatomy, sheet plastination

Introduction

Knowledge of the anatomy of the anal sphincter complex (ASC) is a prerequisite to understanding its normal function and the mechanisms underlying defaecatory disorders. This knowledge is of importance to surgeons, sonographers, radiologists and radiotherapists, in order to diagnose faecal incontinence, fistula tracts and tumours, plan appropriate interventions, and evaluate postoperative results (Kashyap & Bates, 2004; Macchi et al. 2008). Lack of understanding of the anatomy of the ASC makes functional assessment problematic and may hinder adequate reconstruction of the anal sphincters during the primary repair. It is therefore clinically important to develop a complete and accurate concept of the anatomy of the ASC (Courtney, 1950; Morgan, 1950; Lunniss & Phillips, 1992; Macchi et al. 2008).

The variability in nomenclature and description of the different components of the ASC adds to the confusion surrounding this complex structure. Examples of this variability include descriptions of the external anal sphincter (EAS) being comprising of one part (Hussain et al. 1995) or three parts (Morgan, 1950; Sultan et al. 1994a). There is also controversy regarding the origin, termination, structure and relation of the conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) (Shafik, 1976; Ayoub, 1979; Cornella et al. 2003; Kashyap & Bates, 2004; Thakar & Fenner, 2007; Hall et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2007; Shafik et al. 2007; Macchi et al. 2008; Noakes et al. 2008;Norderval et al. 2008; Thekkinkattil et al. 2008).

The descriptions of the ASC based on gross anatomical dissections propose a structure that may differ from that identified by histological sections or sonographic images. Anal endosonography has become the primary investigation to diagnose anal sphincter defects in clinical practice; however, in living subjects it is difficult to confirm that structures identified on ultrasound correspond to the actual anatomical structure (Sultan et al. 1994a,b; Cornella et al. 2003; Fornell et al. 2005; Felt-Bersma & Cazemier, 2006; Hall et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2007; Shafik et al. 2007; Valsky et al. 2007; Norderval et al. 2008).

To overcome the limitation of one or other of the techniques used previously to study this region, the present investigation was carried out using multiple approaches. Concomitant anatomical dissection and sonography of the same specimens was adopted. Furthermore, the structural details and dimensions of the ASC were elucidated by the combination of examination of thin transparent E12 plastinated coronal and axial sections together with conventional histological microscopy.

Materials and methods

Human cadavers were bequeathed to the Department of Anatomy with Radiology at the University of Auckland for teaching and research under the terms of the Human Tissue Act 1964. Eighteen male cadavers, with an average age of 72 years (range 62–82 years), were used in this study. The cadavers were embalmed by arterial perfusion using carotid and/or femoral arteries. The vascular perfusion started with prewash with Metaflow arterial conditioner followed by embalming fluid (Dodge Company, USA).

Gross anatomy dissection

The pelvic regions from embalmed cadavers were used. The perianal skin and the fat in the ischioanal fossa were removed to expose the anal canal and the lower surface of the levator ani muscles. A longitudinal incision was made on the lateral side of the anal canal to expose the layers of the ASC, namely the EAS, CLM and internal anal sphincter (IAS).

E12 epoxy resin sheet plastination

For E12 resin sheet plastination, two undissected pelves were excised and stored at –80 °C for 4 days. One pelvis was serially sliced coronally and the other was serially sliced axially into 2.5 mm thick sections using a high-speed band saw. The slices were dehydrated in acetone for freeze substitution and degreasing. The slices were then transferred into methylene chloride solution for rendering the slices transparent. Forced impregnation (under vacuum) was used to replace the fluid in the tissue slices with epoxy resin polymer (E12). The resin-impregnated slices were allowed to cure as detailed previously (Cook & Al-Ali 1997). Coronal sections parallel to the long axis of the anal canal were achieved by placing a 1 × 10 cm polyurethane rod into the anal canal and rectum prior to freezing. This straightening of the anorectal angle also occurs on insertion of an endoanal ultrasound probe.

Histological staining

For histological investigation, longitudinal and axial sections of the anal canal were cut, processed and embedded in wax. Sections measuring 6 mm were cut and stained using haematoxylin and eosin, Masson's trichrome and elastic van Gieson stain techniques. The slides were examined with a bright-field light microscope (Leica DMRB, equipped with Nikon DS-U1 digital camera) and a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ16) equipped with Leica DFC290 digital camera.

Endosonography

A total of eight male cadavers were used for endosonography. The ultrasonography was performed using a BK Medical 2003 Cheetah ultrasound device with a rotating transducer (type 1850) to produce an axial image of 360°. A transducer tip (type 6005) designed to accommodate imaging of the rectum and anal canal was selected. The mechanical 10 MHz endoprobe was used in conjunction with a water-filled 22 mm endopiece. Anal endosonography was performed in situ, followed by resection of the anal canal from the pelvis. The layers of the anal canal were removed serially from the external to the internal aspect, with repeated endosonography following the removal of each layer. Special care was taken to avoid stretching of the layers. Ultrasound images were captured using the Ulead VideoStudio 7 (Taiwan) software.

Measurements

Measurements of the dissected anatomical specimens and the correlated endosonographic images were performed at a level of approximately the middle of the excised anal canal specimens. Following the removal of each layer, the remaining thickness of the ASC was measured on gross anatomical specimens and on the endosonographic images in four quadrants. A single measurement was taken for each quadrant in each specimen. A process of numerical subtraction of adjacent measurements allowed calculation of the thickness of each of the layers of the ASC as they were identified in dissection and on endosonography. A software package Image-J(National Institute of Health) was used to obtain measurements from the endosonographic images. An assessment of the appearance of the ASC on endosonography was made via visual subtraction of adjacent images allowing identification of layers as sequential external dissection was performed. The average thicknesses of the ASC layers in gross anatomical specimens and their endosonographic equivalent images were determined. Full thickness measurements taken prior to removal of layers were compared with the sum of the thicknesses of the component layers. All measurements were performed by one of the authors (S.B.).

Results

The three layers of the ASC were clearly seen in gross dissection, E12 thin-sheet plastination, histological sections and on ultrasonography (Figs 1–4).

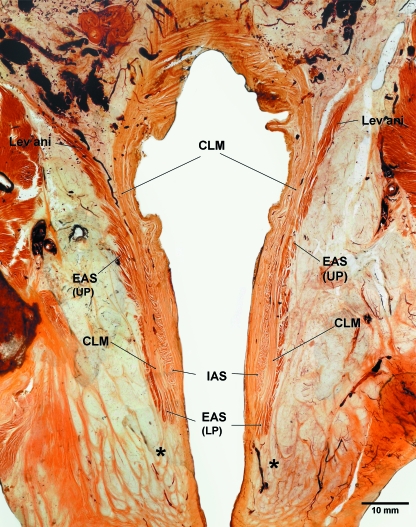

Fig. 1.

A transilluminated 2.5 mm thick coronal section of a male pelvis processed for epoxy resin E12 sheet plastination showing the entire length of the anal canal and its muscular layers, namely the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). Note the continuity of the EAS with the levator ani muscle superiorly, consisting of two parts, the upper part [EAS (UP)] and lower part [EAS (LP)]. The upper part of the CLM is continuous with the longitudinal muscular layer of the rectum and inferiorly its fibres traverse the lower part of the EAS to blend with or form fibro-fatty honeycomb-like compartments around the perianal region (asterisks). The IAS ends above the lower part of the EAS.

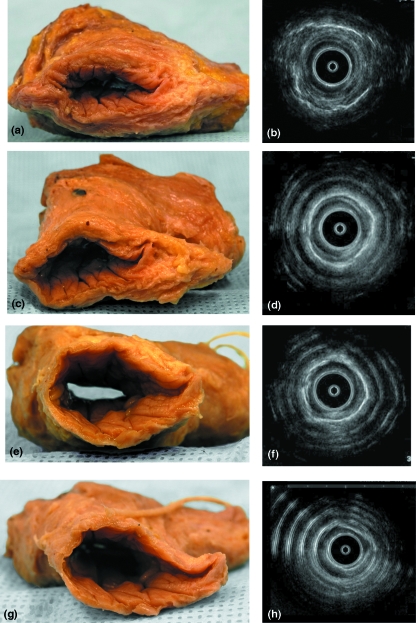

Fig. 4.

An excised anal canal specimen showing sequential removal of its muscular layers (a,c,e,g) and their corresponding endoanal sonographic images (b,d,f,h). Full thickness of the anal canal (a,b), after the removal of the external anal sphincter (c,d), after the removal of the conjoint longitudinal layer (e,f) and after the removal of the internal anal sphincter (g,h). Note that the ring-shaped artefacts on the sonographic images are due to the effect of the air/tissue interface in this ex-vivo preparation.

External anal sphincter

The EAS consisted of skeletal muscular fibres and was a continuous layer around the anal canal. It appeared as a continuous structure with no evidence of division into three separate muscular bellies (Fig. 1). Superiorly the EAS blended with the puborectalis and inferiorly it extended below the IAS. At its inferior end it curved inward and was pierced by the fibroelastic septa of the CLM (Figs 1, 2e). The coronal E12 section also illustrated the orientation of muscular fibres of the EAS, vertical or oblique in the upper part (representing the deep and superficial parts in the traditional description), whereas in the lower part (representing the subcutaneous part in the traditional description) the fibres were seen encircling the anal canal inferior to the IAS. It was the only muscle surrounding the anal orifice at this level. Axial E12 sections showed that some fibres decussate anterior and posterior to the anal canal (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

The anal canal and its muscular layers, external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). (a) Gross anatomical dissection, (b) longitudinal slice of the lateral wall of the anal canal, (c) longitudinal histological section, haematoxylin and eosin stain, (d) longitudinal histological section, elastic van Gieson stain and (e) longitudinal histological section, Mason's trichrome stain.

Fig. 3.

Axial sections of the anal canal and its muscular layers, namely the external anal sphincter (EAS), poorly identified conjoint longitudinal layer (*) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). (a) Epoxy resin E12 sheet plastination, (b) histological section, haematoxylin and eosin stain, (c) histological section, Mason's trichrome stain and (d) endoanal sonographic image of the layers of the anal canal.

Conjoint longitudinal muscle

In gross dissection the CLM was identified as a thick fibromuscular fatty layer interposed between the EAS and IAS (Fig. 2a,b). Longitudinal histological sections and E12 coronal sections revealed that the muscular part of the CLM consisted of smooth muscle only and it was continuous with the outer longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum (Fig. 1). The fibroelastic part of the CLM fanned out in different directions piercing the IAS medially and EAS laterally. Inferiorly the fibres of the CLM passed through the lower part of the EAS to reach the perianal dermis (Figs 1, 2d,e). As the fibres traversed the lower part of the EAS, it formed fibromuscular pockets (compartments) containing skeletal muscle fibres derived from the lower part of the EAS (Figs 1, 2e). The CLM fibres blend or form fibro-fatty compartments around the lower part of the anal canal giving the honeycomb appearance of the region (Fig. 1, asterisks).

Internal anal sphincter

The IAS was clearly seen as a continuation of the circular muscle layer of the rectum (Figs 1, 3). It gradually thickened as the anal canal passed through the pelvic floor. The IAS ended above the lower part of the EAS (Figs 1, 2). Externally it was covered by the fibres of the CLM with some fibres of the CLM traversing the IAS.

Endosonography

Sequential removal of the layers of the ASC by dissection with concomitant endosonography revealed all layers of the ASC anatomically and their corresponding ultrasound images (Figs 3d, 4). The endosonographic images were adequate for correlation and data analysis in the specimens; however, the air/tissue interface in this excised preparation caused ring-shaped artefacts (Fig. 4b,d,h). The EAS appeared as a thick irregular and relatively hyperechoic band. External to the EAS, a thin hyperechoic band was identified, representing the air/muscle interface. The CLM appeared as an irregular hyperechoic line between the IAS and EAS. The IAS was readily identifiable as a thick regular hypoechoic band. Endosonography demonstrated the anoderm and subcutaneous tissue to be a narrow hyperechoic band, compressed by the endosonographic probe (Figs 3d, 4).

Measurements

The results of the present study showed variability depending on the method used (Tables 1–4). The results are given as means ± S.D. of all specimens measured in four quadrants. The average thickness of the wall of the anal canal (in mm) was 8.95 ± 1.91 in dissection, 11.09 ± 1.35 in sonographic images and 12.9 ± 0.7 in sheet plastination. The average thickness (in mm) of the EAS was 2.16 ± 1.08 in dissection, 3.55 ± 1.11 in sonographic images and 3.58 ± 0.68 in sheet plastination. The average thickness (in mm) of the CLM was 1.71 ± 1.1 in dissection, 2.48 ± 0.58 in sonographic images and 2.36 ± 0.48 in sheet plastination. The average thickness (in mm) of the IAS was 2.2 ± 0.91 in dissection, 2.36 ± 0.86 in sonographic images and 3.28 ± 0.3 in sheet plastination.

Table 1.

The average measurements (in mm) obtained from the dissection and concomitant endosonography of the excised anal canal

| Full thickness |

EAS |

CLM |

IAS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample no. | Dissection | Ultrasound | Dissection | Ultrasound | Dissection | Ultrasound | Dissection | Ultrasound |

| 1 | 8.0 ± 2.4 | 11.3 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

| 2 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 8.0 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9 |

| 3 | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 1.2 |

| 4 | 10.9 ± 2.3 | 11.2 ± 1.6 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.7 |

| 5 | 10.4 ± 1.5 | 10.7 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| 6 | 8.3 ± 1.9 | 12.7 ± 1.8 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.1 |

| 7 | 9.0 ± 1.8 | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 0.8 |

| 8 | 10.5 ± 2.4 | 11.3 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| Average | 8.95 ± 1.91 | 11.09 ± 1.35 | 2.16 ± 1.08 | 3.55 ± 1.11 | 1.71 ± 1.1 | 2.48 ± 0.85 | 2.2 ± 0.91 | 2.36 ± 0.86 |

The muscular layers of the anal canal are the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS) The results are given as means ± S.D. measured in four quadrants.

Table 4.

The average measurements (in mm) of the layers of the anal canal presented by other investigators

| Histology topography |

Ultrasonography |

MRI |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Macchi et al. (2008) 52–72 years M & F | Hall et al. (2007) 23–45 years F | Gerdes et al. (1997) 38–83 years M & F | Poen et al. (1997) 24–75 years M & F | Sultan et al. (1994a) 18-67 years M & F | Schafer et al. (1994) 25–40 years M & F | Hussain et al. (1995) 21–26 years M & F | Schafer et al. (1994) 25–40 years M & F |

| EAS | 2.95 ± 0.89 | 1.45–1.84 | 6.20 (4.5–7.1) EAS & CLM | 8.3 ± 1.3 (M) 6.9 ± 1.1 (F) | 7.8 ± 1.3 (M) 7.1 ± 1.2 (F) | 6.35 ± 1.07 | 3.0 (2–5) | 3.96 ± 0.99 |

| CLM | 1.68 ± 0.27 | NA | NA | NA | 2.9 ± 0.6 (M) 2.5 ± 0.6 (F) | NA | 1.3 (1–1.5) | NA |

| IAS | 2.69 ± 0.53 | 2.49–2.73 | 2.54 (1.73–3.0) | 1.3 ± 0.4 (M) 1.8 ± 0.8 (F) | 1.9 ± 0.6 (M) 1.8 ± 0.5 (F) | 1.96 ± 0.61 | 2.5 (2–4) | 1.71 ± 0.12 |

The muscular layers of the anal canal are the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). F, female; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

Despite the fact that few regions in human anatomy have received more attention than the ASC, its detail remains contentious and unclear to both anatomists and clinicians. Additionally, variations are common in this region (Sultan et al. 1994a). A multimodal approach was used in an attempt to gain a better understanding of the ASC. The different approaches complemented each other and provided a better understanding of the region. Gross anatomical dissection with concomitant sonography in cadavers allowed for accurate identification of the layers of the ASC on sonography, which can be used for clinical correlation. Straightening the anorectal angle followed by coronal and axial sectioning and transforming the slices into thin transparent E12 resin slices gave insights into the accurate identification, extent and relations of the different layers of the ASC. Furthermore, the E12 sheet plastination technique bridged the gap between gross and microscopic anatomy (Cook & Al-Ali, 1997).

The EAS has traditionally been described, in both anatomy textbooks and journal articles, as consisting of three parts: deep, superficial and subcutaneous (Dalley, 1987; Moore et al. 2006; Sinnatamby & Last, 2006) but others have denied such subdivisions (Goligher et al. 1955; Hussain et al. 1995; Konerding et al. 1999; Fritsch et al. 2002). These different and inconsistent descriptions were also reported by investigators using ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (Dalley, 1987; Hussain et al. 1995; Peschers et al. 1997; Rociu et al. 2000; Fritsch et al. 2002; Gray & Standring, 2005; Hsu et al. 2005; Moore et al. 2006; Sinnatamby & Last, 2006). This study revealed that the EAS consisted of a continuous layer that can be divided into two parts only on the basis of its relation to the IAS. The upper part represented the traditional description of the deep and superficial parts (Courtney, 1950; Morgan & Thompson, 1956). The lower part was equivalent to the traditional subcutaneous part that encircles the anal orifice (Courtney, 1950; Hollinshead, 1971; Hussain et al. 1995; Konerding et al. 1999; Fritsch et al. 2002). Therefore, the traditional division of the EAS into three parts (deep, superficial and subcutaneous) is an arbitrary one and, furthermore, the terms superficial and subcutaneous were confusing and have at times been used interchangeably.

Similarly, there have been several different descriptions of the CLM, such as its connections and its muscular types (Courtney, 1950; Morgan & Thompson, 1956; Macchi et al. 2008). The use of the E12 transillumination technique and histological staining elucidated the structure and connections of the CLM. The present study revealed that its upper muscular part consisted of smooth muscle fibres, whereas the lower part consisted of multiple fibroelastic fascial strata. The latter ran in different directions, inwards through the IAS, outwards through the EAS and inferiorly through the lower part of the EAS to reach the perianal dermis. These strata created fat-containing pockets that resulted in a honeycomb appearance of the lower perianal region, which was well demonstrated in E12 transparent sections.

Although anal endosonography is a well-established procedure for the evaluation of anorectal pathology, the identification of even normal structures varies considerably. Consequently there has been controversy regarding the identification of the layers of this region (Gerdes et al. 1997; Huang et al. 2007). In this study, the sequential gross anatomical dissection with concomitant sonography allowed direct identification and measurement of individual layers of the ASC on both dissection and endosonographic images. The submucosa was hyperechoic and the IAS was hypoechoic on anal endosonography. The EAS appeared as an irregular mixed-echogenic structure. The identification and appearance of the CLM, however, remained controversial. Beets-Tan et al. (2001) showed that the CLM was hypoechoic and found within hyperechoic intersphincteric space on endosonography. Sultan et al. (1994b) stated that the CLM was identifiable in all male and 40% of female volunteers and that it was hyperechoic relative to the EAS. Gerdes et al. (1997) reported that the EAS and CLM were occasionally differentiated; however, the present study could not precisely delineate the CLM on endoanal sonography and on the axial (E12 and histological) sections.

In the present study, the EAS and IAS were clearly visible in all specimens. The CLM was poorly identifiable as a thin band of a similar echogenic appearance to the EAS and separated by a thin hypoechoic fascial plane. Reassessment of the initial full-thickness endosonographic images was performed with particular attention to the identification of the CLM. This was again visualized as an indistinct band, similar in echotexture to the EAS but nonetheless visually distinct to the observer aware of the position and nature of this structure. The tissue plane was identified following comparison of the images before and after the removal of the EAS and the tissue boundaries were estimated. Sequential removal by dissection of each layer and concomitant sonography allowed identification and classification of the layers in cases where the similarity of the echotexture of both the EAS and CLM would have otherwise hindered measurement. A probe of higher megahertz may have shown better resolution of these two structures. In this study, by using a number of modalities, the EAS and CLM have been demonstrated as distinct entities in dissection and coronal sectioning but indistinct on ultrasound and axial, E12 and histological sections. This discrepancy is due to the fact that the vertical orientation fibres of the CLM do not show well on axial sections.

Correlation of the measurements obtained from the different methods used in the present investigation showed some variations in thickness as detailed in Tables 1–3. Interestingly, the measurements of the ASC obtained by other investigators also varied widely (Table 4) using different methods such as histology (Macchi et al. 2008), anal endosonography (Schafer et al. 1994; Sultan et al. 1994a; Gerdes et al. 1997; Poen et al, 1997) and magnetic resonance imaging (Schafer et al. 1994). Although the ASC is visualized and measurable on transanal ultrasonography (Nicholls et al. 2006), the reproducibility of measurements is relatively poor and has been questioned by other investigators (Poen et al, 1997; Beets-Tan et al. 2001). In addition to the normal variation between individuals there are multiple other factors that may have an impact on these measurements including age, gender, method of embalming, length of the time before embalming and whether CLM was inadvertently added or excluded in the measurements. The results of this study suggest that anal endosonography may not be robust at providing accurate measurements of the layers of the ASC. Sultan et al. (1994a) identified the individual layers in most subjects but in the present investigation the CLM was less readily identifiable than the other two layers. The overall absence of absolute correlations between dissection and sonography suggests that although endosonography is useful for visualizing relationships between tissues and tissue integrity, it lacks the ability to provide accurate absolute measurements in the embalmed cadaver, a finding that may also translate into the living subject in clinical practice. These measurements should therefore be used with caution in diagnosis and management.

The average measurements (in mm) obtained from the dissection, ultrasound and E12 sheet plastination

| Method | Dissection | Ultrasound | E12 sheet plastination |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAS | 2.16 ± 1.08 | 3.55 ± 1.11 | 3.58 ± 0.68 |

| CLM | 1.71 ± 1.1 | 2.48 ± 0.85 | 2.36 ± 0.48 |

| IAS | 2.2 ± 0.91 | 2.36 ± 0.86 | 3.28 ± 0.3 |

| Full thickness | 8.95 ± 1.91 | 11.09 ± 1.35 | 12.9 ± 0.7 |

The muscular layers of the anal canal are the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). The results are given as means ± S.D. of all specimens measured in four quadrants.

Table 2.

The average measurements (in mm) obtained from the axial E12 sheet plastination of the anal canal

| E12 sheet plastination | EAS | CLM | IAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slice 1 (lower level) | 3 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Slice 2 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 3 ± 0.5 |

| Slice 3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 3 ± 0.5 |

| Slice 4 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| Slice 5 (higher level) | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 2 ± 0 | 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| Average | 3.58 ± 0.68 | 2.36 ± 0.48 | 3.28 ± 0.3 |

The muscular layers of the anal canal are the external anal sphincter (EAS), conjoint longitudinal muscle (CLM) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). The results are given as means ± S.D. measured in four quadrants.

Concluding remarks

By using a multimodal approach the three layers of the ASC were identified and compared with their ultrasonographic appearance. The EAS appeared as a continuous structure with no evidence of division into three separate muscular bellies. The EAS can be divided into two parts only on the basis of its relation to the IAS. The upper part represented the traditional description of the deep and superficial parts. The lower part was equivalent to the traditional subcutaneous part that encircles the anal orifice distal to the lower end of the IAS.

The CLM was demonstrated to be a fibro-fatty-muscular layer occupying the intersphincteric space. It continued superiorly with the longitudinal muscular layer of the rectum, being made up of smooth muscle fibres. The lower part consisted of collagen and elastic fibres with fatty tissue filling the spaces between the fibrous septa. The vertical orientation of its fibres was well demonstrated on longitudinal and coronal sections but was poorly identifiable in axial sections and on ultrasound.

As previously described the IAS was the markedly thickened part of the terminal circular smooth muscle layer of the rectum ending above the lower part of the EAS. On endoanal sonography the EAS was identified as an irregular hyperechoic band. The CLM was less well defined and appeared as a thin irregular hyperechoic line and the IAS was represented by a clear hypoechoic band.

Measurements of the muscle thicknesses of the ASC in human males varied depending on whether they were obtained by dissection, sonography, histology or E12 plastination. These variations were also encountered by other investigators and therefore the measurements should be used with caution in diagnostic and management settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor S. Heap, Dr V. Grant, Dr P. Malpas, Dr S. Amirapu, Mr N. Duggan, Mr P. Cook, Mr J. Manson and Mr T. Roberts for their valuable contribution to this project and for helping our surgical anatomy research option students who worked on this region. The work was supported by the University of Auckland Research Option Fund.

References

- Table 3.Ayoub SF. Anatomy of the external anal sphincter in man. Acta Anat (Basel) 1979;105:25–36. doi: 10.1159/000145103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beets-Tan RG, Morren GL, Beets GL, et al. Measurement of anal sphincter muscles: endoanal US, endoanal MR imaging, or phased-array MR imaging? A study with healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2001;220:81–89. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jn1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P, Al-Ali SYA. Submacroscopic interpretation of human sectional anatomy using plastinated E12 sections. J Int Soc Plast. 1997;12:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cornella JL, Hibner M, Fenner DE, Kriegshauser JS, Hentz J, Magrina JF. Three-dimensional reconstruction of magnetic resonance images of the anal sphincter and correlation between sphincter volume and pressure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:130–135. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney H. Anatomy of the pelvic diaphragm and anorectal musculature as related to sphincter preservation in anorectal surgery. Am J Surg. 1950;79:155–173. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(50)90208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley AF. The riddle of the sphincters. The morphophysiology of the anorectal mechanism reviewed. Am Surg. 1987;53:298–306. 2nd. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felt-Bersma RJ, Cazemier M. Endosonography in anorectal disease: an overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;243:165–174. doi: 10.1080/00365520600664292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjodahl R, Berg G. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long term effects. BJOG. 2005;112:312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch H, Brenner E, Lienemann A, Ludwikowski B. Anal sphincter complex: reinterpreted morphology and its clinical relevance. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:188–194. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes B, Kohler HH, Zielke A, Kisker O, Barth PJ, Stinner B. The anatomical basis of anal endosonography. A study in postmortem specimens. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:986–990. doi: 10.1007/s004649900508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goligher JC, Leacock AG, Brossy JJ. The surgical anatomy of the anal canal. Br J Surg. 1955;43:51–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004317707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H, Standring S. Gray's Anatomy: the Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall RJ, Rogers RG, Saiz L, Qualls C. Translabial ultrasound assessment of the anal sphincter complex: normal measurements of the internal and external anal sphincters at the proximal, mid-, and distal levels. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:881–888. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinshead W. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper and Row; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y, Fenner DE, Weadock WJ, DeLancey JO. Magnetic resonance imaging and 3-dimensional analysis of external anal sphincter anatomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1259–1265. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000189084.82449.fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Yang SH, Yang JM. Three-dimensional transperineal sonographic characteristics of the anal sphincter complex in nulliparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:210–220. doi: 10.1002/uog.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain SM, Stoker J, Lameris JS. Anal sphincter complex: endoanal MR imaging of normal anatomy. Radiology. 1995;197:671–677. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.3.7480737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap P, Bates N. Magnetic resonance imaging anatomy of the anal canal. Aust Radiol. 2004;48:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2004.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konerding MA, Dzemali O, Gaumann A, Malkusch W, Eckardt VF. Correlation of endoanal sonography with cross-sectional anatomy of the anal sphincter. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:804–810. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunniss PJ, Phillips RK. Anatomy and function of the anal longitudinal muscle. Br J Surg. 1992;79:882–884. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi V, Porzionato A, Stecco C, Vigato E, Parenti A, De Caro R. Histo-topographic study of the longitudinal anal muscle. Clin Anat. 2008;21:447–452. doi: 10.1002/ca.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CN. Surgical importance of the composite longitudinal muscle of the anal canal, external sphincter and levator ani muscles. Am J Surg. 1950;79:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(50)90207-8. Discussion, 173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CN, Thompson HR. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal with special reference to the surgical importance of the internal sphincter and conjoint longitudinal muscle. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1956;19:88–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls MJ, Dunham R, O’Herlihy S, Finan PJ, Sagar PM, Burke D. Measurement of the anal cushions by transvaginal ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1410–1413. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes KF, Bissett IP, Pullan AJ, Cheng LK. Anatomically realistic three-dimensional meshes of the pelvic floor and anal canal for finite element analysis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:1060–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9471-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norderval S, Markskog A, Rossaak K, Vonen B. Correlation between anal sphincter defects and anal incontinence following obstetric sphincter tears: assessment using scoring systems for sonographic classification of defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:78–84. doi: 10.1002/uog.5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschers UM, DeLancey JO, Fritsch H, Quint LE, Prince MR. Cross-sectional imaging anatomy of the anal sphincters. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:839–844. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poen AC, Felt-Bersmaa RJF, Devilléc W, Cuestaa MA, Meuwissenb SGM. Normal values and reproducibility of anal endosonographic measurements. Eur J Ultrasound. 1997;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Lameris JS. Normal anal sphincter anatomy and age- and sex-related variations at high-spatial-resolution endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;217:395–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer A, Enck P, Furst G, Kahn T, Frieling T, Lubke HJ. Anatomy of the anal sphincters. Comparison of anal endosonography to magnetic resonance imaging. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:777–781. doi: 10.1007/BF02050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafik A. A new concept of the anatomy of the anal sphincter mechanism and the physiology of defecation. III. The longitudinal anal muscle: anatomy and role in anal sphincter mechanism. Invest Urol. 1976;13:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafik A, El Sibai O, Shafik IA, Shafik AA. Stress, urge, and mixed types of partial fecal incontinence: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and treatment. Am Surg. 2007;73:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnatamby CS, Last RJ. Last's Anatomy: Regional and Applied. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Nicholls JR, Bartram CI. Endosonography of the anal sphincters: normal anatomy and comparison with manometry. Clin Radiol. 1994a;49:368–374. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan AH, Loder PB, Bartram CI, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Vaginal endosonography. New approach to image the undisturbed anal sphincter. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994b;37:1296–1299. doi: 10.1007/BF02257800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakar R, Fenner DE. Anatomy of the Perineum and the Anal Sphincter. London: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thekkinkattil DK, Lim M, Stojkovic SG, Finan PJ, Sagar PM, Burke D. A classification system for faecal incontinence based on anorectal investigations. Br J Surg. 2008;95:222–228. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsky DV, Messing B, Petkova R, et al. Postpartum evaluation of the anal sphincter by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in primiparous women after vaginal delivery and following surgical repair of third-degree tears by the overlapping technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:195–204. doi: 10.1002/uog.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]