Abstract

Objective

To test whether the Communities That Care (CTC) prevention system reduces adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use and delinquent behavior community wide.

Design

The Community Youth Development Study is the first randomized trial of CTC.

Setting

24 small towns in 7 states, matched within state, were randomly assigned to control or CTC conditions in 2003.

Participants

A panel of 4407 fifth-grade students was surveyed annually through eighth grade.

Intervention

A coalition of community stakeholders received training and technical assistance to install CTC. They used epidemiologic data to identify elevated risk factors and depressed protective factors in the community and chose and implemented tested programs to address their community’s specific profile from a menu of effective programs for youths aged 10 to 14, their families and schools.

Outcome Measures

Incidence and prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use and delinquent behavior by spring of grade 8.

Results

The incidences of delinquent behavior, alcohol, cigarette, and smokeless tobacco initiation were significantly lower in CTC than in control communities between grades 5 and 8. In grade 8, the prevalences of alcohol and smokeless tobacco use in the last 30 days, binge drinking in the past 2 weeks, and the number of different delinquent behaviors committed in the past year in grade 8 were significantly lower in CTC communities.

Conclusions

Using the CTC system to reduce health risking behaviors among adolescents can significantly reduce these behaviors community wide.

Introduction

Health risking behaviors, including tobacco use, alcohol use, and delinquent behavior, have large costs to society.1–4 Their incidence and prevalence increase dramatically during early adolescence from the ages of 11 through 15. The initiation of these behaviors early in adolescence is predictive of greater risk for associated health-related diseases and disorders.5–8 For example, Hingson et al.9 found that 45% of adults who began drinking by age 14 became dependent on alcohol at some point in their lifetimes versus 9% who began drinking at age 21 or later. Nationally, in 2007, 39% of eighth graders had ever drunk alcohol, 22% had smoked cigarettes, 9% had used smokeless tobacco, and 14% had used marijuana.10 Delinquency often precedes drug use initiation in early adolescence11, 12 and is, itself, an important target for prevention. Thirty-eight percent of deaths in the United States are attributable to smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity, and diet.1 Rather than waiting until tobacco has caused cancer, or alcohol use has turned to abuse or dependence, or delinquency has become chronic offending leaving a trail of victims, the prevention of delinquency and the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs during early adolescence should be important public health priorities.13–15

Advances in prevention science over the past 2 decades have produced a growing list of tested and effective programs and policies for preventing these behaviors.16–19 Yet, widespread dissemination and high-quality implementation of these effective programs and policies in communities has not been achieved.20–23 Woolf24 has urged greater emphasis on the conduct of type 2 (T2) translational research to understand how research advances such as these can be translated into widespread practice in communities. He suggests that T2 translational prevention efforts need to involve multiple sectors in the community and should not be limited to clinical settings where time to provide preventive services is limited and expensive.25 A community-driven, community-wide effort to reduce health risking behaviors, coordinated across health, education, and human service sectors, should significantly reduce health risking behaviors community wide, though Woolf25 notes that this hypothesis is “largely untested” (p. 2439). Prior efforts to activate coalitions of community stakeholders to prevent problems such as drug abuse community wide have not been successful.26

Communities That Care (CTC)27, 28 is a prevention system created to provide training and materials that mobilize and empower coalitions of diverse community stakeholders to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency by using the advances of prevention science.29 CTC coalitions use the CTC Youth Survey to assess levels of empirically identified risk and protective factors for these behaviors in the community30–33 and use the CTC Prevention Strategies Guide to choose and implement tested preventive interventions to address those risk factors that are elevated in the community. New programs are put in place in appropriate collaborating organizations in the community after staff are trained to deliver the new programs. Implementation of these programs is monitored by the CTC coalition.

A small number of previous efforts to mobilize communities for the prevention of adolescent health risking behaviors have been tested and found to have positive effects. CTC differs from these efforts. Unlike the Midwestern Prevention Project34, 35 36 and Project Northland,37 CTC does not prescribe that specific programs be implemented in a preset order, but rather allows the local coalition to choose programs that best address the community’s profile of risk and protection from a menu of tested programs. Unlike Project Northland,37 Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol,38 and the Community Trials Intervention to Reduce High Risk Drinking,39, 40 CTC does not focus exclusively on the prevention of alcohol use but rather on reducing risk factors that predict early alcohol initiation and use as well as other health risking behaviors, including delinquency, in hopes of reducing multiple negative outcomes predicted by common risk factors. Unlike PROSPER,41 CTC does not prescribe that the prevention coalition should be headed by a county extension agent and a representative from the school sector, but allows stakeholders from a variety of organizations in the community to take leadership in the coalition. The CTC system has been implemented in the United States, the UK, the Netherlands, Canada, and Australia. It is distributed by the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. All CTC materials are available on the internet.42 Nonrandomized evaluations of CTC indicate that it helps communities to develop more effective prevention services systems43–46 and can reduce levels of risk exposure and adolescent drug use community wide.47

The Community Youth Development Study (CYDS)48 is the first community-randomized trial of CTC. It is designed to determine whether CTC reduces levels of risk, increases levels of protection, and reduces the incidence and prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use and delinquency in early adolescence in communities. The CTC system is expected to produce community-level changes in prevention service system characteristics, including greater adoption of science-based prevention, increased collaboration among service providers, and increased use, with better implementation, of tested and effective prevention programs that address risk and protective factors prioritized by the community. These changes in prevention service systems are expected to produce reductions in the risk factors targeted by the prevention programs chosen by the community. These reductions in risk factors are expected, in turn, to reduce delinquent behaviors and substance use among young people in the community. According to CTC’s theory of change, it should take from 2 to 5 years to observe community-level changes in targeted risk factors, and from 5 to 10 years to observe community-level changes in adolescent tobacco use, alcohol use, and delinquency outcomes.49

Earlier analyses from the CYDS have found that the CTC system had been successfully implemented with fidelity in intervention communities50 and have found significant between-condition differences favoring the CTC communities in levels of adoption of science-based prevention and in levels of community collaboration.51 Analyses also have found that tested and effective preventive programs were selected and well implemented in the CTC communities.48 Hypothesized effects of CTC on targeted risk factors and on the incidence of delinquent behavior have been observed 3 years after implementation of CTC in communities.48 This paper reports the effects of CTC on the community-wide incidence and prevalence of delinquent behavior and tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use among eighth-grade students in a panel followed from grade 5 through grade 8, 4 years after implementation of CTC in communities and 2.67 years after CTC communities began implementing prevention programs selected through the CTC process.

Methods

Community Selection and Assignment

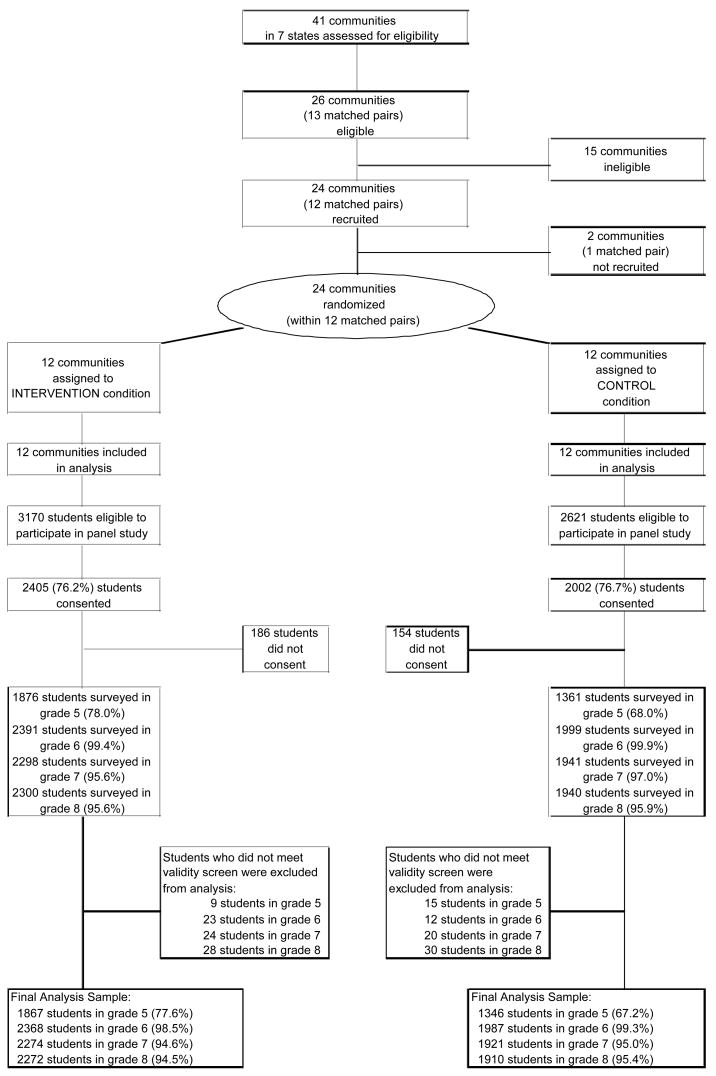

Communities in the CYDS were selected from 41 communities in the states of Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Oregon, Utah, and Washington that participated in an earlier naturalistic study of the diffusion of science-based prevention strategies, called the Diffusion Project.52 The drug abuse prevention agencies in these states identified 20 of these communities that the agencies thought were trying to implement risk- and protection-focused prevention services. These 20 communities were then matched, within state, on population size, racial and ethnic diversity, economic indicators, and crime rates to comparison communities that were not thought to be using a risk and protection-focused approach, and the 20 community pairs were recruited to participate in the Diffusion study. In one instance, 2 comparison communities were identified, resulting in a total of 41 communities. In spite of states’ initial assessments of these communities, during the 5 years of the Diffusion Project, neither community in 13 of the 20 pairs of communities advanced in the use of science-based prevention to the point of selecting and using tested, effective preventive interventions to address prioritized community risks.43, 53 These 13 pairs of communities were deemed eligible for inclusion in the CYDS study. Twelve of these pairs of matched communities were recruited for the CYDS. One community from within each matched pair was assigned randomly by a coin toss to either the intervention (CTC) or control condition. Demographic characteristics of the 24 communities are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the flow of communities through the trial.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 24 CYDS Communities

| Control Communities | CTC Communities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Total populationa | 13,996 | 1,921 | 32,885 | 15,236 | 1,578 | 40,787 |

| Percent Caucasiana | 89.5 | 71.4 | 98.0 | 89.3 | 64.0 | 98.2 |

| Percent Hispanica | 9.2 | 0.6 | 42.9 | 10.1 | 0.5 | 64.7 |

| Percent African American (of juvenile population under age 18)a | 2.5 | 0.0 | 20.3 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 21.1 |

| Percent eligible for free/reduced school lunchb | 38.2 | 20.6 | 63.0 | 34.9 | 20.7 | 65.9 |

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Communities and Participants

CTC Implementation

CTC training and implementation began in the summer of 2003. Intervention communities received 6 CTC trainings delivered over the course of 6 to 12 months by certified CTC trainers. Community leaders were oriented to the CTC system and identified or created a community coalition of diverse stakeholders to implement CTC. Coalition members were trained to use data from surveys of community students collected in 1998, 2000, and 2002 in the prior study52 to prioritize risk factors to be targeted by preventive actions in the community; to choose tested and effective prevention policies and programs that address the community’s targeted risk factors; to implement these interventions with fidelity; and to monitor implementation and outcomes of newly installed prevention programs. CTC communities in CYDS were asked to focus their prevention plans on programs for youths aged 10 to 14 years (grades 5 through 9) and their families and schools. CYDS implementation staff provided technical assistance through weekly phone calls, emails, and site visits to CTC communities at least once per year. By June of 2004, coalitions in intervention communities had selected prevention programs to address their prioritized risk factors and had created plans to implement these programs with fidelity. The 12 intervention communities selected 13 different tested and effective prevention programs to implement during the 2004–2005 school year, 16 programs to implement during the 2005–2006 school year, and 14 programs for implementation during the 2006–2007 school year. These included school-based programs (All-Stars, Life Skills Training, Lion’s Quest Skills for Adolescence, Project Alert, Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, and Program Development Evaluation Training), community-based, youth-focused programs (Participate and Learn Skills, Big Brothers/Big Sisters, Stay Smart, and academic tutoring), and family-focused programs (Strengthening Families 10–14, Guiding Good Choices, Parents Who Care, Family Matters, and Parenting Wisely).50, 54 Each year, community coalitions implemented from 1 to 5 of these programs to address their own community profiles. On average, 3 programs were implemented per community each year. The new programs were implemented by local providers, including teachers for school programs; health and human service workers for community-based, youth-focused, and family-focused programs; and community volunteers for tutoring programs and Big Brothers/Big Sisters.

Programs selected were required to have been found to be effective in well-controlled trials in preventing tobacco, alcohol, or other drug use or delinquent behavior among youths in grades 5 though 9. Therefore, for this trial, alcohol policy changes (e.g., tax increases, social host liability, keg registration, etc.) were not implemented as part of the trial.55 However, policies and changes in policies related to tobacco, alcohol, and crime were monitored in both intervention and control communities through the study period.

Sample and Data Collection

Data on adolescent drug use and delinquent behavior were obtained from annual surveys of a panel of public school students who were in the fifth grade during the 2003–2004 school year in the 24 CYDS communities. Recruitment for the student panel began in the fall of 2003 by mailing information packets and making in-person calls to each school district superintendent and elementary and middle school principal within the 24 CYDS communities, asking for their commitment to participate in the study and outlining the requirements of involvement in the coming year. As a result, 28 of 29 school districts, comprising 88 schools, agreed to participate. All students in fifth-grade classrooms during the 2003–2004 school year in these schools were eligible to participate in the study. The first wave of data, collected in the spring of 2004, was a pre-intervention baseline assessment. Tested prevention programs were implemented in CTC communities beginning in the summer and fall of 2004. The fourth annual wave of data was collected in the spring of 2007 when panel students progressing normally were in grade 8, about 2.67 years after the prevention programs chosen by CTC communities were first implemented.

Grade 6 (Wave 2) data collection included an effort to recruit students who were not surveyed in grade 5. During grades 5 and 6, parents of 4420 students (76.4% of the eligible population) consented to their participation in the study (see Figure 1). Final consent rates did not differ significantly by intervention condition. Consent rates were 76.1% for students in intervention communities and 76.7% for students in control communities. Eleven percent (n = 404) of the students consented in Wave 1 were ineligible for participation in Wave 2 because they moved out of the school district before participating in the study for one semester (n = 388), did not remain in their grade cohort (i.e., skipped or were held back a grade; n = 4), were in foster care and did not have consent from state authorities to participate (n = 7), or were unable to complete the survey on their own due to severe learning disabilities (n = 5). Thirteen of the 4420 consented students were absent during scheduled dates of data collection and were not available for initial surveying. The final active longitudinal panel consisted of 4407 students (2194 girls, 2213 boys; 55% from intervention communities) in 77 elementary and middle schools in grade 6 (41 schools in intervention communities and 36 schools in control communities). Students in the longitudinal panel who remained in intervention or control communities for at least one semester have been tracked and surveyed at each of the following waves, even if they left the community. Ninety-six percent of students in the longitudinal panel completed the survey in Wave 4 (grade 8).

Students completed the Youth Development Survey (YDS),56 a self-administered, paper-and-pencil questionnaire designed to be completed in a 50-minute classroom period. To ensure confidentiality, identification numbers but no names or other identifying information were included on the surveys. Parents of panel students provided written informed consent for their children’s participation in the study. Students read and signed assent statements indicating that they were informed fully of their rights as research participants and agreed to participate in the study. Upon completion of the survey, students received small incentive gifts worth approximately $5 to $8. The University of Washington’s Human Subjects Review Committee has approved this protocol.

Measures

Delinquent Behavior

The incidence of delinquent behavior was operationalized as the first self-reported occurrence of any of 4 delinquent acts (stealing, property damage, shoplifting, attacking someone) between grades 5 and 8. More serious delinquent behaviors (including carrying a gun to school, beating up someone, stealing a vehicle, selling drugs, and being arrested) were added to the eighth-grade survey as developmentally appropriate. A measure of the variety of delinquent acts committed in the past year ranging from 0 to 9 was constructed from the eighth-grade data.

Drug Use

Items measuring the incidence of drug use consisted of the first student-reported use of alcohol, cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, marijuana, and inhalants between grades 5 and 8 (e.g., “Have you ever smoked a cigarette, even just a puff?”). The prevalences (with any use dichotomized as 1 and no use as 0) of binge drinking (consuming 5 or more drinks in a drinking occasion) during the past 2 weeks and use of alcohol, cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, marijuana, and inhalants in the past month were measured in grades 5 and 8 (e.g., “On how many occasions (if any) have you had beer, wine, or hard liquor during the past 30 days?”). Grade 8 measures also included the prevalence of use of prescription drugs and other illicit drugs (i.e., psychedelics, MDMA [“ecstasy”], stimulants, and cocaine) in the past month. Baseline descriptives for the panel are shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in prevalence rates or means between panel participants in intervention communities and those in control communities in grade 5.

Table 2.

Observed Drug Use Prevalence Rates and Mean Number of Delinquent Behaviors Reported in Grade 5 by Experimental Condition

| Control Communities (2002 students) | CTC Communities (2405 students) | |

|---|---|---|

| Drug use | ||

|

| ||

| Lifetime | ||

| Alcohol, % | 23.3 | 20.1 |

| Cigarettes, % | 9.4 | 7.4 |

| Smokeless tobacco, % | 2.8 | 2.0 |

| Inhalants, % | 8.6 | 8.5 |

| Marijuana, % | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Past 30 days | ||

| Alcohol, % | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Cigarettes, % | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Smokeless tobacco, % | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Inhalants, % | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Marijuana, %a | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Past 2 weeks | ||

| Binge drinking, % | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Delinquent behavior | ||

| Past year | ||

| Mean number of delinquent behaviors | 0.4 | 0.3 |

Prevalence of 30-day marijuana use based on unimputed data (1861 students in CTC communities and 1342 students in control communities). All other figures based on average across 40 imputations. Differences between CTC and control communities were not significant.

Student and Community Characteristics

Variables measuring student characteristics used as covariates in analyses included: age at time of the grade 6 survey; gender (coded 0 = male, 1 = female); race/ethnicity (coded 0 = other, 1 = White or Caucasian); whether the student was Hispanic (coded 1 = yes, 0 = no); parental education level (ranging from 1 = grade school or less to 6 = graduate or professional degree); attendance at religious services during grade 5 (coded 0 = never to 4 = about once a week or more); and rebelliousness in grade 5, which consisted of the mean of 3 items (alpha = .69): I like to see how much I can get away with; I ignore rules that get in my way; and I do the opposite of what people tell me, just to get them mad (coded from 1 = very false to 4 = very true). Variables measuring community demographic characteristics included the total population of students in the community, percentage increase in the student population of the community between 2001 and 2004, and the percentage of students who were eligible for free or reduced price school lunch. Intervention condition was coded 0 for CTC communities and 1 for control communities.

Analysis Sample and Missing Data Procedures

Among the 4407 students comprising the consented longitudinal panel, 26.5% were recruited in Wave 2 (grade 6 accretion sample) and consequently did not complete a questionnaire in Wave 1 (grade 5). A small proportion of students were not available for follow-up interviews as shown in Table 3. Overall, 96.7% of panel students participated in at least 3 of 4 waves of data collection. There was no systematic bias due to differential accretion or differential attrition in control and intervention conditions (analyses not shown). With regard to both accretion and attrition, the methods for imputing missing data used in this study have been shown in simulations by Collins, Schafer, and Kam57 and extensions by Graham (2009 –personal communication) to produce estimates of standard errors that differ little from population values.

Table 3.

Analysis Sample of Students

| Wave 1 (Grade 5) | Wave 2 (Grade 6) | Wave 3 (Grade 7) | Wave 4 (Grade 8) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | |

| Total consented sample | 4407 | (100.0) | 4407 | (100.0) | 4407 | (100.0) | 4407 | (100.0) |

| Not surveyed | 1170 | (26.5) | 17 | (0.4) | 168 | (3.8) | 167 | (3.8) |

| Surveyed | 3237 | (73.5) | 4390 | (99.6) | 4239 | (96.2) | 4240 | (96.2) |

| Of those surveyed: | ||||||||

| Did not meet validity screen because: | ||||||||

| Dishonest | 13 | (0.4) | 21 | (0.5) | 17 | (0.4) | 18 | (0.4) |

| Use of fictitious drug | 8 | (0.2) | 11 | (0.3) | 19 | (0.4) | 18 | (0.4) |

| Extreme drug use | 1 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.0) | 4 | (0.1) | 6 | (0.1) |

| Combination | 2 | (0.1) | 2 | (0.0) | 4 | (0.1) | 16 | (0.4) |

| Total excluded | 24 | (0.7) | 35 | (0.8) | 44 | (1.0) | 58 | (1.4) |

| Analysis sample | 3213 | (72.9) | 4355 | (98.8) | 4195 | (95.2) | 4182 | (94.9) |

Students were excluded from analysis if they reported being honest only “some of the time” or less on the survey, reported having used a fictitious drug included in the survey as a validity screen, or reported that they had used 2 of 3 drugs (marijuana, inhalants, or other drugs) on 40 or more occasions during the past month as shown in Table 3).

The proportion of students in the analysis sample who did not respond to the delinquency and drug use questions was small. Item nonresponse ranged from 0.6% (for smokeless tobacco use in grade 5) to 2.7% (for specific delinquency items in grades 7 and 8). Missing data were dealt with via multiple imputation.58 Using NORM version 2.03,59 40 separate data sets including data from all 4 waves were imputed separately by intervention condition.60 Imputation models included student and community characteristics, drug use and delinquent behavior outcomes, and community membership. Imputed data sets were combined subsequently to include both intervention and control groups for analysis.

Data Analyses

Intervention effects on the incidence and prevalence of delinquency and drug use were assessed using the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM)61–63 with logit or Poisson link functions for the dichotomously coded (i.e., incidence and prevalence of drug use and delinquency) or count-based outcomes (i.e., variety of delinquent acts), respectively. Random-intercept models were estimated to account for variation across time within students, among students within communities, and communities within matched pairs of communities.

Analyses were adjusted for the student- and community-level covariates (grand-mean centered) described above. In all analyses, results were averaged across imputed data sets using Rubin’s rules.64 Approximate degrees of freedom across imputations were calculated using the formulas provided by Raudenbush et al.65;66

To account for the fact that communities were matched in pairs before randomization, the intervention effect for the community-level dichotomous indicator of intervention status (0 = control community, 1 = CTC community) was estimated as the mean difference in adjusted community-level prevalence/incidence rates between intervention and control communities as tested against the average variation among the intervention condition-specific adjusted community-level prevalence/incidence rates, with degrees of freedom equal to the number of community-matched pairs (12) minus the number of community-level covariates and intervention effect (3), minus one (i.e., df = 8)63.

Incidence of Delinquency, Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drug Use in Early Adolescence

The effect of the CTC intervention in preventing the incidence of delinquency and drug use between grades 5 and 8 was examined using multilevel discrete-time survival analysis (ML-DTSA).67, 68 The risk of initiating delinquent behavior and drug use was assessed for those students in the sample who had not yet initiated delinquent behavior (78.8%), alcohol use (78.5%), cigarette use (91.7%), smokeless tobacco use (97.6%), marijuana use (99.4%), or the use of inhalants (91.4%), respectively, prior to the grade 5 survey. The dichotomous outcomes in the ML-DTSA indicate whether initiation had occurred during the preceding annual wave of data collection. In each respective analysis, students initiating delinquent behavior or use of a specific drug in one grade were not eligible for initiation of that behavior in subsequent grades. Students who did not initiate delinquent behavior or drug use during sixth, seventh, or eighth grade were treated as right-censored observations.69

To test whether the effect of the intervention on incidence was proportional across time, we included interaction effects between the intervention condition variable and time indicators. All analyses were estimated with MLwiN version 2.02,70 using the second-order penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL) estimator whenever possible. The second-order PQL estimator did not converge for analyses of the onset of smokeless tobacco, marijuana, and inhalant use. The first-order PQL estimator was used instead.

Prevalence of Delinquency and Drug Use

The effect of the CTC intervention on reducing the prevalence of past-year delinquency, drug use in the past month, and binge drinking in the past 2 weeks in grade 8 was assessed using a mixed-model ANCOVA. In addition to student and community characteristics, respective grade 5 delinquency or drug use measures were included as pre-intervention covariates to adjust for any potential baseline differences. The mixed model ANCOVA was conducted using HLM version 6.0.65

To determine whether CTC had an overall effect on drug use incidence and prevalence by grade 8, and to maintain an effective Type I error rate of .05, an omnibus Group Test Statistic71 was applied to both the ML-DTSA and mixed-model ANCOVAs before analyses of effects on specific drugs.

Results

Incidence of Drug Use

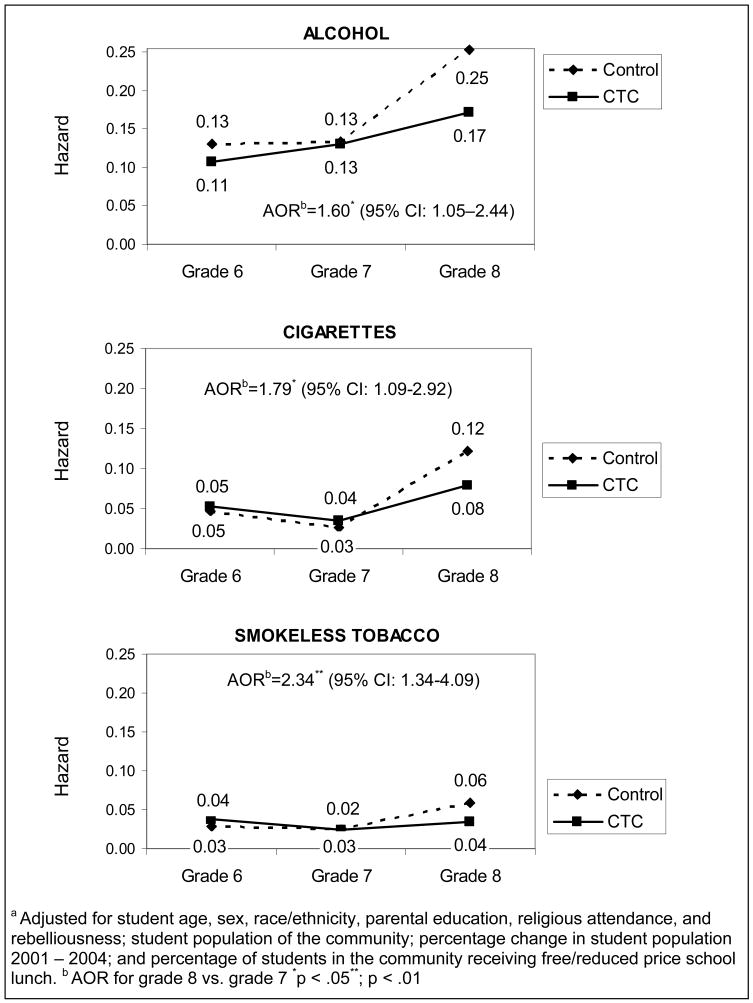

The omnibus test for overall effects on drug use incidence was statistically significant, t (8) = 2.72, p < .05 (2-tailed). Analyses found a significant effect of CTC on the initiation of the use of alcohol, cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco between seventh and eighth grade. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for the effect of CTC on alcohol use incidence was 1.60, indicating that students in control communities were 60% more likely to initiate the use of alcohol between grade 7 and grade 8 than students in CTC communities. The AORs for the effect of CTC on the initiation of cigarette and smokeless tobacco use were 1.79 and 2.34, respectively. Figure 2 shows the adjusted predicted hazard of initiating alcohol, cigarette, and smokeless tobacco use. Significant intervention effects on the onset of marijuana or inhalant use in the panel were not observed by the spring of eighth grade (OR = .96 [95% CI: 0.60; 1.53] and OR = 1.12 [95% CI: 0.68; 1.83], respectively).

Figure 2.

Adjusteda Hazard of Initiating the Use of Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Smokeless Tobacco

a Adjusted for student age, sex, race/ethnicity, parental education, religious attendance, and rebelliousness; student population of the community; percentage change in student population 2001 – 2004; and percentage of students in the community receiving free/reduced price school lunch. b AOR for grade 8 vs. grade 7 *p < .05**; p < .01

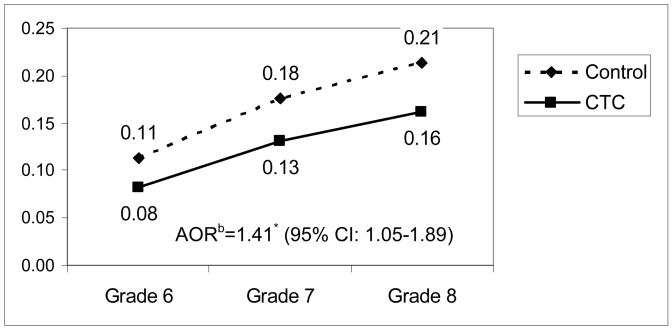

Incidence of Delinquent Behavior

Analyses found a significant intervention effect on the incidence of delinquent behavior between grades 5 and 8. The effect of the intervention on the incidence of delinquency was proportional across time; no significant time-by-intervention interactions were found. The AOR for the effect of the CTC intervention on delinquent behavior initiation was 1.41, indicating that students from control communities were 41% more likely to initiate delinquent behavior between grade 5 and grade 8 than were students from CTC communities. Figure 3 shows that by grade 8 the adjusted predicted hazard of initiating delinquent behavior was 21% for students in control communities and 16% for students in CTC communities.

Figure 3.

Adjusteda Hazard of Initiating Delinquent Behaviors

a Adjusted for student age, sex, race/ethnicity, parental education, religious attendance, and rebelliousness; student population; percentage change in student population 2001 – 2004; and percentage of students in the community receiving free/reduced price school lunch. b AOR for entire time period. *p < .05

Prevalence of Drug Use in Eighth Grade

Table 4 shows the observed prevalences and AORs of drug use in eighth grade in CTC and control communities. The omnibus test for overall effects on current drug use prevalence was statistically significant, t (9) = 2.61, p < .05 (2-tailed). The ANCOVA analyses showed significantly higher prevalences in the eighth grade in control communities compared to CTC communities of alcohol use in the past 30 days, t (9) = 2.48, p < .05 (2-tailed), AOR = 1.25; binge drinking in the past 2 weeks, t (9) = 2.59, p < .05 (2-tailed), AOR = 1.40; and smokeless tobacco use in the past 30 days, t (9) = 3.23, p < .01 (2-tailed), AOR = 1.79. Eighth-grade students in the panel in control and CTC communities did not differ significantly in the prevalence of marijuana, cigarette, inhalant, prescription drug, or other illicit drug use in the past 30 days (t’s (9) = 0.86, 1.47, 0.50, 0.25, and 1.38, respectively).

Table 4.

Observed Prevalence Rates of Current Drug Use and Delinquency in Grade 8 and Adjusted Odds Ratios Comparing Control and CTC Communities

| Control Communities | CTC Communities | AORControl/CTC (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug use | |||

| Past 30 days | |||

| Alcohol, % | 21.4 | 16.4 | 1.25* (1.04–1.52) |

| Cigarettes, % | 8.0 | 6.1 | 1.21 (0.92–1.58) |

| Smokeless tobacco, % | 4.3 | 2.2 | 1.79** (1.23–2.62) |

| Inhalants, % | 5.0 | 4.8 | 1.11 (0.73–1.68) |

| Marijuana, % | 6.0 | 4.7 | 1.15 (0.82–1.60) |

| Prescription drugs, % | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.05 (0.72–1.52) |

| Other illicit drugs, % | 3.6 | 2.2 | 1.30 (0.88–1.92) |

| Past 2 weeks | |||

| Binge drinking, % | 9.0 | 5.7 | 1.40* (1.07–1.84) |

| Delinquent behavior | |||

| Past year | |||

| Number of delinquent behaviors (0–9), Mean | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.34** (1.20–1.49) |

Odds ratios are adjusted for grade 5 prevalence, student age, sex, race/ethnicity, parental education, religious attendance, and rebelliousness; student population of the community; and percentage of students in the community receiving free/reduced price school lunch. Alcohol use in past 30 days in grade 5 was used to adjust analyses of 8th-grade marijuana, prescription drug, and other illicit drug use.

p < .05

p < .01

Variety of Delinquent Behaviors in the Past Year

Analyses assessing delinquent behaviors found that students in control communities engaged in significantly more delinquent behaviors than students in CTC communities in the year prior to the eighth-grade survey, t (9) = 5.43, p < .01 (2-tailed), AOR = 1.34, as shown in Table 4.

Comment

Woolf25 has suggested that the prevention of the early onset of disease is an important strategy for confronting America’s co-occurring problems of rapidly increasing health care spending and the increasing burden of disease as the population ages. He has noted that chronic diseases accounting for large majorities of health care spending are precipitated by modifiable risk factors. Advances in prevention science identifying risk factors for drug use and delinquency and identifying tested, effective prevention programs and policies have guided the development of the Communities That Care system. The system mobilizes diverse community stakeholders to work together to reduce elevated risk factors in the community. Stakeholder coalitions seek to achieve this goal through high-quality and faithful replication of previously tested, effective programs that address these risks. This study shows that within 4 years of adopting the CTC system, community coalitions can reduce the incidence of delinquent behaviors and of alcohol, tobacco, and smokeless tobacco use as well as the prevalence of alcohol use, binge drinking, smokeless tobacco use, and delinquent behavior among young people community wide by the age of 14.

This evidence that the early initiation of alcohol use, tobacco use, and delinquency can be prevented by coalition efforts is important. The early initiation of these behaviors has negative consequences. For example, those who initiate drinking before age 15 are 4 times as likely to develop alcohol dependence as those who wait until age 21 or older; each additional year of delay in drinking reduces the likelihood of dependence by 14 percent.72 Underage drinking also predicts unintentional injuries, motor vehicle crashes, physical fights after drinking both during adolescence and adult years, and is associated with risky sexual behavior, mental health problems including depression and suicide attempts, and a variety of violent and delinquent behaviors.55 Thus, simply delaying the initiation of alcohol use through age 14, even among those who will ultimately drink alcohol, may have long-term public health benefits. Contingent on continued funding, this panel will be followed and interviewed through one year past normal high school graduation to determine the long-term effects of preventing the early initiation of alcohol use, tobacco use, and delinquency observed here.

This type 2 translational research study indicates that the public health can be promoted and health risking behaviors in early adolescence can be prevented by coalitions of community stakeholders trained to use the Communities That Care system for translating the advances of prevention science into well-chosen and well-implemented prevention practices in communities. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention provides Communities That Care materials electronically for downloading free of charge. However, federal resources are not currently available to support training and technical assistance in CTC for communities that seek to use it.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA015183-03) with co-funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: J. David Hawkins had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Hawkins, Oesterle, Brown, Arthur, Catalano, Abbott, Fagan

Acquisition of data: Hawkins, Fagan, Arthur, Catalano

Analysis and interpretation of data: Oesterle, Brown, Hawkins, Abbott, Arthur, Catalano

Drafting of the manuscript: Oesterle, Hawkins, Brown

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hawkins, Oesterle, Brown, Fagan, Arthur, Catalano, Abbott

Statistical analysis: Oesterle, Brown, Abbott

Obtained funding: Hawkins, Arthur, Catalano

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hawkins, Fagan

Study supervision: Hawkins, Arthur, Catalano

Financial Disclosure: Richard F. Catalano is a board member of Channing Bete Company, distributor of Supporting School Success ® and Guiding Good Choices ®. These programs were used in some communities in the study that produced the data set used in this paper.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or preparation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Contributions: Steven Raudenbush Ph.D. (University of Chicago), David Murray, Ph.D. (Ohio State University), and John W. Graham, Ph.D. (Penn State University) provided paid statistical consultation on this study, but the authors are responsible for all analyses and results.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the communities participating in the Community Youth Development Study and the collaborating state offices of drug abuse prevention in Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Oregon, Utah, and Washington.

Some of the information in this paper was previously presented at the May 5–10, 2008 meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, the May 27–31, 2008 meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, and at a research briefing for NIH staff at the National Institute on Drug Abuse on July 15, 2008.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH. The big answer: rediscovering prevention at a time of crisis in health care. Harvard Health Policy Rev. 2006;7(2):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Specter A. Making youth violence prevention a national priority. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3, Supplement 1):S3–S4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Criminology. 2003;41(3):555–592. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robins LN, Przybeck TR. Age of onset of drug use as a factor in drug and other disorders. In: Jones CL, Battjes RJ, editors. Etiology of Drug Abuse: Implications for Prevention (NIDA Research Monograph No. 56) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1985. pp. 178–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrington DP. Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues - The 2002 Sutherland Award Address. Criminology. 2003;41(2):221–255. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence - Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2006. Volume I: Secondary School Students. (NIH Publication No. 07–6205) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandel DB, Simcha Fagan O, Davies M. Risk factors for delinquency and illicit drug use from adolescence to young adulthood. J Drug Issues. 1986;16(1):67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard S. Multiple Problem Youth: Delinquency, Substance Use, and Mental Health Problems. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woolf SH. Potential health and economic consequences of misplaced priorities. JAMA. 2007;297(5):523–526. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 11, 2008];2004 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/sgr_2004/index.htm. [PubMed]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration--U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed September 5, 2007];Report to Congress: A Comprehensive Plan for Preventing and Reducing Underage Drinking. Available at: http://www.stopalcoholabuse.gov/media/underagedrinking/pdf/underagerpttocongress.pdf.

- 16.Aos S, Lieb R, Mayfield J, Miller M, Pennucci A. Benefits and Costs of Prevention and Early Intervention Programs for Youth. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mihalic S, Fagan A, Irwin K, Ballard D, Elliott D. Blueprints for Violence Prevention (NCJ 204274) Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile and Delinquency Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed September 5, 2007];Science-based Prevention Programs and Principles. Effective Substance Abuse and Mental Health Programs for Every Community. Available at: http://download.ncadi.samhsa.gov/prevline/pdfs/BKD479.pdf.

- 19.Welsh BC, Farrington DP. Evidence-based crime prevention. In: Welsh BC, Farrington DP, editors. Preventing Crime. What Works for Children, Offenders, Victims, and Places. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2006. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL, Thorne J, et al. A comparison of current practice in school-based substance use prevention programs with meta-analysis findings. Prev Sci. 2003;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1021777109369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottfredson DC, Gottfredson GD. Quality of school-based prevention programs: Results from a national survey. J Res Crime Delinquency. 2002;39(1):3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallfors D, Godette D. Will the ‘Principles of Effectiveness’ improve prevention practice? Early findings from a diffusion study. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):461–470. doi: 10.1093/her/17.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wandersman A, Florin P. Community interventions and effective prevention. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6–7):441–8. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolf SH. The power of prevention and what it requires. JAMA. 2008;299(20):2437–2439. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallfors D, Cho H, Livert D, Kadushin C. Fighting back against substance abuse: Are community coalitions winning? Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Investing in Your Community’s Youth: An Introduction to the Communities That Care System. South Deerfield, MA: Channing Bete; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW. Promoting science-based prevention in communities. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):951–976. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, et al. The science of prevention. A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, Baglioni AJ., Jr Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: The Communities That Care Youth Survey. Eval Rev. 2002;26(6):575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arthur MW, Briney JS, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Brooke-Weiss BL, Catalano RF. Measuring risk and protection in communities using the Communities That Care Youth Survey. Eval Program Plan. 2007;30(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser RR, Van Horn ML, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Measurement properties of the Communities That Care Youth Survey across demographic groups. J Quant Criminol. 2005;21(1):73–102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fagan AA, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Using community epidemiologic data to improve social settings: The Communities That Care prevention system. In: Shinn M, Yoshikawa H, editors. Toward Positive Youth Development: Transforming Schools and Community Programs. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 292–312. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pentz MA, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, et al. A multi-community trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse: Effects on drug use prevalence. JAMA. 1989;261(22):3259–3266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pentz MA, Trebow EA, Hansen WB, MacKinnon DP. Effects of program implementation on adolescent drug use behavior: The Midwestern Prevention Project (MPP) Eval Rev. 1990;14(3):264–89. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou CP, Montgomery S, Pentz MA, et al. Effects of a community-based prevention program in decreasing drug use in high-risk adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):944–948. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry C, Williams CL, Komro KA, et al. Project Northland: Long-term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(1):117–132. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagenaar AC, Gehan JP, Jones-Webb R, et al. Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol: Lessons and results from a 15-community randomized trial. J Community Psychol. 1999;27(3):315–326. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grube JW. Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: results from a community trial. Addiction. 1997;92(Suppl 2):S251–S260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holder HD, Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, et al. Effect of community-based interventions on high-risk drinking and alcohol-related injuries. JAMA. 2000;284(18):2341–2347. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Clair S, Feinberg M. Substance-use outcomes at 18 months past baseline: The PROSPER community-university partnership trial. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed October 31, 2007];Communities That Care Planning System. Available at: http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/features/ctc/resources.aspx.

- 43.Arthur MW, Ayers CD, Graham KA, Hawkins JD. Mobilizing communities to reduce risks for drug abuse: A comparison of two strategies. In: Bukoski WJ, Sloboda Z, editors. Handbook of Drug Abuse Prevention. Theory, Science and Practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenson JM, Hartman JC, Smith JR, Draayer D, Schurtz R. Evaluation of Iowa’s Juvenile Crime Prevention Community Grant Fund Program. Iowa City: University of Iowa, School of Social Work; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenberg MT, Feinberg M, Gomez BJ, Osgood DW. Testing a community prevention focused model of coalition functioning and sustainability: A comprehensive study of Communities That Care in Pennsylvania. In: Stockwell T, Gruenewald P, Toumbourou JW, Loxley W, editors. Preventing Harmful Substance Use: The Evidence Base for Policy and Practice. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2005. pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harachi TW, Ayers CD, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Cushing J. Empowering communities to prevent adolescent substance abuse: Process evaluation results from a risk- and protection-focused community mobilization effort. J Prim Prev. 1996;16(3):233–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02407424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feinberg ME, Greenberg MT, Osgood DW, Sartorius J, Bontempo D. Effects of the Communities That Care model in Pennsylvania on youth risk and problem behaviors. Prev Sci. 2007;8(4):261–270. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fagan AA, Hanson K, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW. Bridging science to practice: Achieving prevention program implementation fidelity in the Community Youth Development Study. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):235–249. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. [Accessed August 11, 2008];Communities That Care Community Board Orientation: Participant’s Guide. Available at: http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/features/ctc/resources.aspx.

- 50.Quinby RK, Fagan AA, Hanson K, Brooke-Weiss B, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD. Installing the Communities That Care prevention system: Implementation progress and fidelity in a randomized controlled trial. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(3):313–332. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW, Briney JS, Abbott RD. Effects of Communities That Care on prevention services systems: Outcomes from the Community Youth Development Study at 1.5 years. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):180–191. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arthur MW, Glaser RR, Hawkins JD. Steps towards community-level resilience: Community adoption of science-based prevention programming. In: Peters RD, Leadbeater B, McMahon RJ, editors. Resilience in Children, Families, and Communities: Linking Context to Practice and Policy. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, et al. Testing Communities That Care: The rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the Community Youth Development Study. Prev Sci. 2008;9(3):178–190. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fagan AA, Hanson K, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW. Implementing effective community-based prevention programs in the Community Youth Development Study. Youth Violence Juvenile Justice. 2008;6(3):256–278. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spoth R, Greenberg M, Turrisi R. Preventive interventions addressing underage drinking: state of the evidence and steps toward public health impact. Pediatr. 2008;121(Suppl 4):S311–336. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Social Development Research Group. Community Youth Development Study, Youth Development Survey [Grades 5 – 7] Seattle, WA: Social Development Research Group, School of Social Work, University of Washington; 2005–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Meth. 2001;6(4):330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol Meth. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schafer JL. NORM for Windows 95/98/NT Version 2.03. University Park, PA: Center for the Study and Prevention through Innovative Methodology at Pennsylvania State University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, Cumsille PE. Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychol Meth. 2006;11(4):323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breslow N, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-randomized Trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT., Jr . HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barber JS, Murphy S, Axinn WG, Maples J. Discrete-time multilevel hazard analysis. Sociol Methodol. 2000;30(1):201–235. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reardon SF, Brennan RT, Buka SL. Estimating multi-level discrete-time hazard models using cross-sectional data: Neighborhood effects on the onset of adolescent cigarette use. Multivariate Behav Res. 2002;37(3):297–330. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3703_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rasbash J, Browne W, Healy M, Cameron B, Charlton C. MLwiN Version 2.02. Bristol, UK: Multilevel Models Project, Institute of Education, University of Bristol; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pocock SJ, Geller NL, Tsiatis AA. The analysis of multiple end-points in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1987;43(3):487–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data, Quick Tables; 2000.

- 74.National Center for Education Statistics. Common Core of Data (CCD) “Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey” 2002–03 v.1a 2003–04 v.1a 2004–05 v.1b 2005–06 v.1a; 2002–2003.