Abstract

Activity schedules are often used to facilitate task engagement and transition for children with autism. This study evaluated whether conditional discrimination training would serve to transfer the control from activity-schedule pictures to printed words (i.e., derived textual control). Two preschoolers with autism were taught to select pictures and printed words given their dictated names. Following training, participants could respond to printed words by completing the depicted task, match printed words to pictures, and read printed words without explicit training (i.e., emergent relations).

Keywords: activity schedules, autism, conditional discrimination, derived stimulus relations, stimulus equivalence

Activity schedules are commonly used to cue children diagnosed with autism to perform tasks independently (McClannahan, MacDuff, & Krantz, 2002). Activity schedules usually consist of binders with one picture per page that children are taught to open, turn the pages, look at the pictures, and engage in the corresponding task (MacDuff, Krantz, & McClannahan, 1993; McClannahan & Krantz, 1999). When children start learning to read, it may be developmentally appropriate to replace the pictures with printed words. Although McClannahan and Krantz recommend using within-stimulus fading for this task, conditional discrimination training (i.e., matching to sample, MTS) may be a viable alternative for transferring control from pictures to printed words in activity schedules (Lalli, Casey, Goh, & Merlino, 1994). One potential advantage of an MTS procedure is the possibility of emergence of untaught responses (i.e., stimulus equivalence). If taught to select pictures when given the dictated names (AB) and printed words when given the same dictated names (AC), participants may match pictures and printed words (BC, CB) and label pictures (BD) and printed words (CD) without direct training (Sidman, 1994).

Rehfeldt and colleagues have demonstrated that learning to relate dictated words to their corresponding pictures and printed words via MTS discrimination training resulted in accurate mands using printed words instead of pictures (Rehfeldt & Root, 2005; Rosales & Rehfeldt, 2007). Other emergent relations were also evident without direct training, including matching words to pictures, pictures to words, and naming pictures and words. Sidman (2004) has suggested that matching words and pictures is a prerequisite for reading with comprehension; thus, MTS seems to be an efficient way to teach socially important skills that should be evaluated with children with autism.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of MTS conditional discrimination training to replace pictures with text in activity schedules of children with autism (i.e., derived textual control). Participants who could follow picture schedules were taught to select pictures and printed words given their dictated names followed by an evaluation of their ability to follow a textual activity schedule. Reading comprehension was also assessed by testing to see if children could match pictures to printed words (and vice versa) and read the words out loud.

METHOD

Participants

Two 6-year-old children who had been diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder participated in the study. Ben spoke in three- to five-word sentences. Dennis spoke in two- to four-word sentences that were almost all prompted. Both had a very limited sight-word vocabulary (i.e., few correct vocal labels for written words).

Setting and Stimulus Materials

Sessions were conducted in a secluded work area of the participants' preschool classroom. Materials included a three ring binder (11.5 cm by 16.5 cm) with one strip of hook-and-loop tape on each of six pages (i.e., activity schedule), a stimulus placement board (50 cm by 19 cm) with three strips of hook-and-loop tape, and 12 laminated cards (5 cm by 7 cm). The 12 cards consisted of six digital photographs of preferred items and six cards with their corresponding printed names in Times New Roman 40-point font on white backgrounds. All items and pictures had previously been trained in picture activity schedules using the procedures outlined by McClannahan and Krantz (1999). Participants had previously been taught to tact each item and picture with 100% accuracy using a prompt delay procedure. Two sets of preferred items and activities were identified via preference assessments (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996). Ben's Set 1 items included a puzzle, a robot toy, and crackers; the Set 2 toys included a shape sorter, a file-folder MTS activity, and chocolate candies. Dennis' Set 1 items included a garage play set, an Etch-a-Sketch, and a Magna Doodle; the Set 2 items were a wooden pizza play set, a pretend medical kit, and chips.

Experimental Design and Measurement

The effects of the MTS conditional discrimination training on completion of textual activity schedules were evaluated using a concurrent multiple-baseline design across two sets of three pictures and toys. All six words were on the schedule in each session but training for one three-item set commenced before training of the other. In addition, pre- and posttests were conducted to assess emergent stimulus relations. The order of conditions was as follows: emergent relations pretests, textual activity-schedule baseline, conditional discrimination training, textual activity-schedule posttraining, and emergent relations posttests (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Order of Training and Testing Conditions

| Condition | Relations | Trained or tested |

| Emergent relations pretest | CB, BC, CDa | Tested |

| Textual activity baseline | C task completion | Tested |

| Conditional discrimination training | AB, AC, and mixed | Trained |

| Textual activity posttraining | C task completion | Tested |

| Emergent relations posttest | CB, BC, CD | Tested |

A = dictated word, B = picture, C = printed word, D = participant's vocal response.

Observers scored whether the presence of printed words on the activity schedule (i.e., derived textual activity control) occasioned correct independent completion of an activity that consisted of looking at a printed word, retrieving the corresponding item from an array (Ben) or bookshelf (Dennis), and either consuming or completing it before flipping to another page. The percentage of correct independent responses was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses by the total possible number of responses per set (three). Observers also scored selections and oral labeling responses during emergent relations tests as correct or incorrect. The percentage of correct responses was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses by the total possible number of responses per block (nine). A second independent observer scored responses during 33% and 60% of the sessions for Ben and Dennis, respectively. Each trial was scored either as an agreement (i.e., identical observer record) or a disagreement. Point-by-point agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the sum of agreements and disagreements, and this ratio was converted to a percentage. Mean interobserver agreement was 92% (range, 78% to 100%) for Ben and 100% for Dennis.

Procedure

Emergent relations pre- and posttests

Relations between pictures and printed words were tested using a typical visual-visual MTS task. The experimenter presented one stimulus (sample), and the participant was required to point to the sample prior to the presentation of the comparisons (i.e., observing response). The experimenter then presented three comparisons attached to the stimulus placement board and asked the participant to “match.” Testing occurred under extinction, in which correct responses were never reinforced and incorrect responses or no response for 5 s resulted in the presentation of the next trial. No additional instructions or prompts were provided.

Testing was arranged in nine-trial blocks in a predetermined order in which samples were each presented three times and comparison stimuli served as the correct comparison once on the right, once in the middle, and once on the left of the bottom array. Emergent conditional relations were tested along with a socially important topography-based response (i.e., reading aloud). First, printed words served as the samples and pictures served as the comparisons (CB). Next, pictures served as the sample and printed words served as comparisons (BC). Emergent textual behavior (i.e., reading aloud) in the presence of printed words was also tested in nine-trial blocks in which each printed word was presented three times with a pointing response and the question, “What is this?” (CD). The criterion for evidence of emergent relations was set at eight of nine (89%) correct trials during a testing block.

Textual activity baseline and posttraining probes

All six pictures in the child's activity schedule were replaced with printed words. Ben's toys and edible items were placed on a table in front of him. Dennis' materials were stored on shelves, and he had already learned to retrieve the items. The experimenter presented the textual activity schedule and said, “Time to use your schedule.” The experimenter sat on a chair approximately 3 m away for data-collection purposes. No adult-mediated reinforcement was provided during the session. Each session consisted of one presentation of the activity schedule. The order of presentation of printed words varied across sessions. Correct responses consisted of completing the activity displayed in the textual stimulus (i.e., printed word). Session length varied depending on the amount of time required for completing each activity or consuming the item, but it never exceeded 20 min. Although sessions would have been terminated if all tasks had not been completed within 25 min, this never happened.

Conditional discrimination training

For each trial, the experimenter presented the vocal sample (A) followed immediately by the stimulus board with the three comparisons (i.e., auditory-visual MTS). The experimenter cued responses by pointing to the correct comparison at a series of five progressive delays (0 s, 1 s, 2 s, 3 s, 4 s, and no prompt) after the presentation of the sample. Criterion to progress through prescribed delays was two consecutive nine-trial blocks with eight of nine correct responses. All correct preprompt responses resulted in praise and tokens that could be exchanged for preferred items at the end of the session. Incorrect responses (i.e., incorrect selections prior to or after the prompt, no selection within 5 s) resulted in re-presentation of the same trial at a 0-s delay. Trials were separated with 3-s intertrial intervals. First, the participant matched dictated words to their corresponding pictures (AB), followed by matching dictated words to their corresponding printed words (AC). Then mixed training was conducted with interspersing trials of the AB and AC relations. The mastery criterion for each relation and the mixed training was two consecutive nine-trial blocks with eight of nine correct unprompted responses (89% accuracy).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

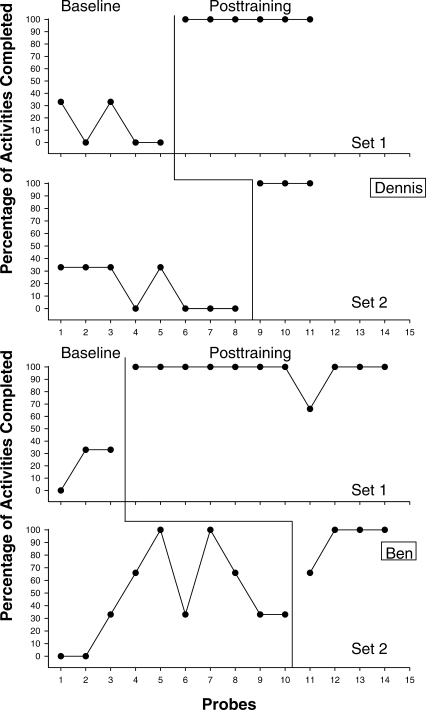

Figure 1 depicts participants' baseline and posttraining performances during textual activity probes. Dennis' baseline percentage of activities completed on both sets was low, and Ben's baseline percentage of activities completed was variable, with increases in accuracy in baseline for the Set 2 items as he mastered the Set 1 items (i.e., three of the six activities were eliminated). These results suggest a lack of specific textual control over participants' behavior prior to MTS training. Ben mastered the conditional discrimination tasks in 261 trials for Set 1 and 153 trials for Set 2, and Dennis mastered the conditional discrimination tasks in 81 trials for Set 1 and 99 trials for Set 2. During the posttraining activity probes, both participants responded accurately across the stimulus sets, with a few errors by Ben. These results suggest that the conditional discrimination procedure was effective in transferring control from the pictures to printed words. In other words, neither child could consistently follow a text-based activity schedule during baseline but both could do so after MTS training on related skills.

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct responses during baseline and posttraining textual activity probes (i.e., correspondence between order of printed activity and engagement in activity).

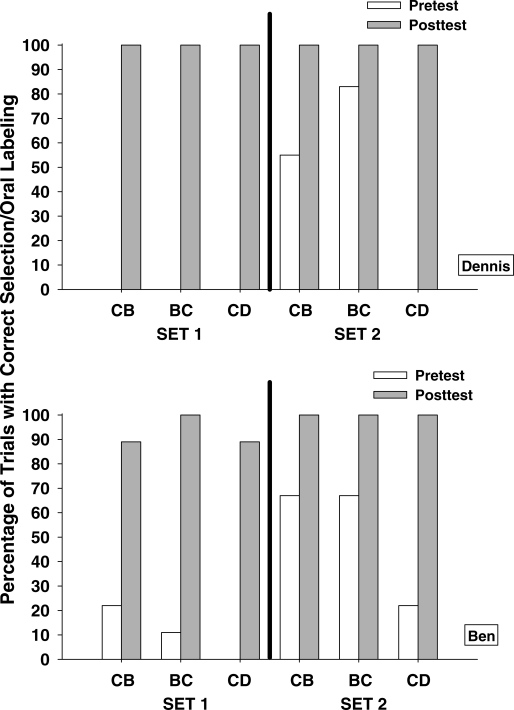

During emergent relations pretests (Figure 2), both participants scored below chance levels for all relations on Set 1 and Set 2. Higher accuracy scores occurred for the BC and CB relations for Set 2 for both participants, but these relatively high pretest scores were still below the success criterion and were not associated with effective use of the textual activity schedules. Emergent relations posttest performances showed that both participants matched words to pictures and pictures to words with at least 89% accuracy. Participants also read all printed words without direct training (CD).

Figure 2.

Percentage of correct responses during emergent relations tests for Stimulus Sets 1 and 2. Emergent relations consisted of CB (selecting the picture in the presence of the printed word), BC (selecting the printed word in the presence of the picture), and CD (reading the printed word).

In summary, after learning to match dictated words to pictures (AB) and dictated words to printed words (AC), children with autism responded to printed words in the same way that they responded to pictures. In addition, participants matched printed words to pictures (CB) and pictures to printed words (BC) and read the printed words aloud (CD) without direct training. The fact that participants were able to match pictures to printed words suggests that they were responding to the printed words with comprehension (Sidman, 1994).

Future research should further evaluate the effectiveness of the conditional discrimination procedure and compare it to within-stimulus fading in order to determine which of these strategies is more efficient and effective when transferring the control from pictures to printed words in activity schedules, as well as whether stimulus fading would yield any form of emergent responding.

Acknowledgments

Caio Miguel is now at California State University, Sacramento. Heather Finn is now at Cabrillo Unified School District, Half Moon Bay, California. We thank Rebecca McDonald and the staff in the Intensive Instruction Program at NECC for their onsite support, as well as Danielle LaFrance for her comments on a previous version of this manuscript. Special thanks go to Linda LeBlanc for her invaluable editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- DeLeon I.G, Iwata B.A. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J.S, Casey S, Goh H, Merlino J. Treatment of escape-maintained aberrant behavior with escape extinction and predictable routines. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:705–714. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDuff G.S, Krantz P.J, McClannahan L.E. Teaching children with autism to use photographic activity schedules: Maintenance and generalization of complex response chains. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:89–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClannahan L.E, Krantz P.J. Activity schedules for children with autism: Teaching independent behavior. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McClannahan L.E, MacDuff G.S, Krantz P.J. Behavior analysis and intervention for adults with autism. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:9–27. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeldt R.A, Root S.L. Establishing derived requesting skills in adults with severe developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:101–105. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.106-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Rehfeldt R.A. Contriving transitive conditioned establishing operations to establish derived manding skills in adults with severe developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:105–121. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.117-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Equivalence relations: A research story. Boston: Authors Cooperative; 1994. [Google Scholar]