Abstract

The present study examined the extent to which mothers were able to train their children, 2 boys with autism, to exchange novel pictures to request items using the picture exchange communication system (PECS). Generalization probes assessing each child's ability to mand for untrained items were conducted throughout conditions. Using a multiple baseline design, results demonstrated that both children improvised by using alternative symbols when the corresponding symbol was unavailable across all symbol categories (colors, shapes, and functions) and that parents can teach their children to use novel pictorial response forms.

Keywords: autism, improvisation, parent training, picture exchange communication system

Augmentative and alternative communication systems such as the picture exchange communication system (PECS) provide an effective means of enabling children with autism or severely limited communication skills to exercise control over their environment by requesting preferred items (Bondy & Frost, 1994). PECS involves teaching individuals to use picture cards to request items or activities. To make picture communication systems more efficient, individuals can be taught to use improvisation. That is, when a specific PECS card representing a preferred item is unavailable, the individual can mand for an item with a picture card that describes the item (e.g., by color, shape, or function). When individuals learn to improvise their requests by using descriptive features of preferred items, they can potentially mand for a much greater number of preferred items with fewer picture cards. Marckel, Neef, and Ferreri (2006) investigated the effects of PECS improvisation training by teaching 2 children with autism to mand for items or activities using picture cards that showed the color, shape, or function of the desired item. Results demonstrated that both children were able to consistently request items using descriptor cards and to generalize the use of the descriptor cards to untrained preferred items. The present study is a systematic replication of Marckel et al. in which the same training procedures were implemented by parents rather than experimenters.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Two children with autism spectrum disorders and their mothers participated in this study. Myles (6 years old) received self-contained special education services and attended a regular first-grade classroom for about 25% of the school day. He had used PECS consistently for 1 year prior to the study. Cliff (5 years old) attended preschool 2 days per week where he received special education services. Cliff started using PECS 4 months before the study began. Both children had been trained to independently mand for preferred items using PECS and met the following criteria for inclusion in this study: (a) an individual education plan recommendation for an augmentative or alternative communication system; (b) a prerequisite repertoire of matching colors, shapes, and functions; and (c) parents' regular use of the PECS system with their children. Both mothers (30 and 45 years old) were Caucasian middle-class high-school graduates.

All sessions were conducted in a quiet area in the participants' homes. Approximately 85% of the sessions were videotaped; data were recorded live during the remaining sessions.

Materials

Preferred foods, drinks, and toys served as the stimuli for the communication exchanges during training and generalization probes. Preferred items for each child were identified through a parent questionnaire and direct observation. Laminated pictures of the preferred items (e.g., graham cracker) and descriptor cards of their characteristics (e.g., brown, square, eat) served as the communication stimuli. Distracter pictures consisted of characteristics that did not match the preferred item (e.g., blue, round, drink). These stimuli were the same form as PECS icons (i.e., Boardmaker drawings, line drawings, clip art).

Preexperimental Assessments

Skill assessment

The experimenter (the first author) used direct observation to assess proficiency with color, shape, and function matching. She showed each child various objects that were red, blue, and yellow and asked him to match the different colors. This assessment procedure was also used for shapes and functions. Both Myles and Cliff were able to match colors, shapes, and functions without prompting to 100% accuracy.

Preference assessment

A list of potentially preferred items was generated for each stimulus category by interviewing the parents. These items were then further assessed with a multiple-stimulus (without replacement) procedure (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996). High- and medium-preference items were used for subsequent training and generalization probes. Items the child chose during the assessment, but did not eat, drink, or play with, were identified as neutral items.

Measurement

Dependent variables

Observers scored child responses in each trial as a correct improvisation, an error, or a nonresponse. A correct improvisation was scored each time a child manded (pointed to or handed) with one or more correct descriptor cards (e.g., brown, square, or eat) for a preferred item (e.g., graham cracker). An error was scored if the child manded with a card that did not correspond to the preferred item (e.g., picture of a square for a round cookie) or for the neutral item (e.g., silver card for paper clip). An error was also scored if the he attempted to mand inappropriately (e.g., moving the adult's hand to the item, grunting and pointing to the item). A nonresponse was scored when the child did not attempt to mand for an item (i.e., did not point to or hand any of the picture cards to his mother, did not attend to any of the items, walked away, or exhibited disruptive behavior).

Procedural integrity of parent implementation

For each condition (baseline, follow-up, and generalization), the experimenter developed a procedural checklist to assess the extent to which mothers accurately implemented the procedures. Observers viewed videotaped sessions and used the procedural checklists to assess procedural integrity of implementation. For each step in each trial, observers scored correct or incorrect implementation of the procedure. Each trial's procedural integrity score was calculated by dividing the number of correctly implemented steps by the total number of steps for the trial. The trial scores were averaged to produce a session score, and then session scores were averaged to summarize procedural integrity of implementation.

Experimental Design

A multiple baseline design across symbol categories (colors, shapes, and functions) was used to examine the effects of parent-implemented training on improvisation of mands, generalization to untrained items, and parent performance. The parent conducted training and follow-up trials on colors until the child achieved mastery during the follow-up probes. The follow-up trials on colors were then followed by training and follow-up probes on shapes and then functions.

Procedure

Parent training

The experimenter taught the mothers how to implement baseline and training procedures using written instructions, explanation, modeling, practice, and feedback. Data collection began after the mother was able to perform the procedures to 90% accuracy on three consecutive trials. If implementation fell below 80% accuracy during the experiment, she were retrained.

Baseline

The mother placed one of the preferred items (e.g., juice pack) in front of the child and the corresponding picture directly below the item. She provided descriptive feedback and praise (e.g., “Good, you asked for the juice pack.”) and brief access to the item (a small bite or sip of food or drink, 30-s access to toys) if the boy pointed to or handed the picture to her (i.e., manded).

An improvisation probe trial was conducted immediately after. The mother moved the pictures out of sight and placed six descriptor symbols (three were characteristics of the preferred item and three were not) in front of the child. If he manded using one or more descriptor cards, she provided brief access to the preferred item. If he made no attempt to mand for the item within 10 s, she moved the preferred item closer to the pictures. If he emitted no response, the trial ended and another trial began. The trial also ended if he attempted to mand with a distracter picture (e.g., circle for juice pack) or reached for the object.

Improvisation training

The mother placed a preferred item (e.g., graham cracker) and a neutral item (e.g., paper clip) in front of the child, along with the corresponding descriptor cards (e.g., brown, silver). If he reached for the preferred item (e.g., graham cracker) instead of manding for the item by pointing to or handing a descriptor card, she guided his hand to the corresponding descriptor card (e.g., brown) and provided brief access to the preferred item (e.g., gave the child a piece of the graham cracker). If he manded for the preferred item using the correct card, she provided brief access to the item and immediate verbal feedback (e.g., “Good, you asked for the graham cracker using the color brown.”).

If the child pointed to or handed the descriptor card of the neutral item, the mother handed the item to the child. If he did not play with the item (or eat or drink the item if it was food or beverage), the item was still considered neutral. The mother then guided the child's hand to the correct picture card (of the preferred item) while stating the color, shape, or function (e.g., “This is brown.”). She then reset the materials and started the trial again. If the child made two consecutive errors, she physically guided his hand to exchange the correct descriptor card on the third trial. The duration of each session ranged from 10 to 30 min. The mother conducted one to three sessions each day, with a minimum of 15 min between sessions. The duration and number of sessions were based on whether or not the child continued to be attentive and cooperative. If he walked away or began displaying noncompliance or disruptive behavior, the training session ended. Following each training session, the mother conducted a follow-up probe to assess the effectiveness of improvisation training.

Follow-up probes

The mother placed the descriptor and distracter cards from all categories in front of the child, along with a preferred item. During the probes that followed training sessions for each category (color, shapes, functions), if the child manded using the symbol for the category that had been trained (e.g., color symbol for color) or a combination of previously trained symbols once the mother had trained more than one symbol (e.g., color and shape for shape, color, shape, and function for function), the mother provided him with brief access to the item. If he manded using an incorrect symbol or emitted no response, she did not provide access to the item and ended the trial. If he used the same symbol to mand for the preferred item more than three times following training for shape and function (i.e., he used the shape symbol to mand for the shape more than three times), she removed the card to promote the use of other potential descriptors. When the child achieved 85% accuracy for three consecutive follow-up probe sessions in one mand category (e.g., colors), improvisation training began in the next category (e.g., shapes). The mother used the same preferred stimuli (five to seven and 10 to 15 items for Myles and Cliff, respectively).

Generalization probes

The experimenter conducted generalization probes in each symbol category throughout the baseline and improvisation conditions. The generalization probes were identical to the follow-up probes with one exception: The stimuli for the generalization probes consisted of untrained preferred items and their corresponding descriptor and distracter cards.

Social validity

Social validity was assessed using an experimenter-designed questionnaire. Parents and significant others were also asked to record any improvisations of mands for untrained items or in untrained settings.

Interobserver Agreement for Children's Responses

A second observer independently scored at least 25% of sessions for each child. An agreement was scored if both observers recorded the same response (e.g., correct improvisation, error, or nonresponse) emitted by the child for a given trial. Agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by agreements plus disagreements and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean agreement was 87% and 93% for Myles and Cliff, respectively.

Interobserver Agreement of Mothers' Implementation

To obtain interobserver agreement data on the extent to which mothers implemented each experimental procedure correctly, two observers assessed at least 25% of the sessions. They independently viewed the videotapes and used procedural integrity checklists to determine whether the mothers correctly followed the procedures in each condition and across symbol categories. The checklists were then examined to determine the number of agreements and disagreements. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by agreements plus disagreements and converting this ratio into a percentage. Mean agreement was 91% (range, 80% to 100%) for Myles' mother and 95% (range, 87% to 100%) for Cliff's mother.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

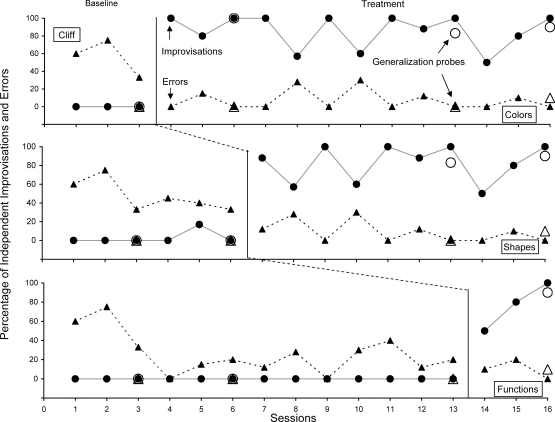

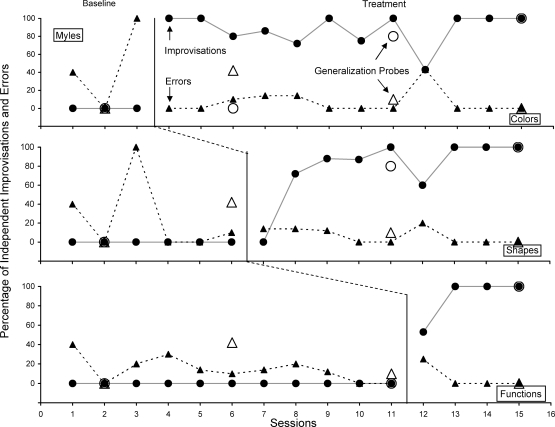

Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the follow-up probes for Cliff and Myles. During baseline, with the exception of Cliff's fifth session for shapes, both children emitted no correct improvisations. Across all baseline sessions, mean percentages of errors and nonresponses were 36% and 63%, respectively, for Cliff and 23% and 67%, respectively, for Myles. When mothers implemented the training condition, there was an immediate and substantial increase in correct improvisations during follow-up probes across categories for both children (Cliff, M = 83%; Myles, M = 84%). Neither boy emitted improvised mands to novel stimuli during baseline, but with the exception of Session 6 for Myles, both boys showed generalization to untrained stimuli during training (range, 80% to 100%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Cliff's correct improvisations (circles) and errors (triangles) during baseline and improvisation training conditions across colors (top), shapes (middle), and functions (bottom). Responses to generalization stimuli are depicted by the open data points.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Myles' correct improvisations (circles) and errors (triangles) during baseline and improvisation training conditions across colors (top), shapes (middle), and functions (bottom). Responses to generalization stimuli are depicted by the open data points.

High percentages of treatment integrity likely contributed to the intervention's effectiveness (M = 97% [range, 88% to 100%] with 100% accuracy on nine of the 15 sessions for Myles' mother and 98% [range, 85% to 100%] with 100% accuracy on 12 of the 16 sessions for Cliff's mother). The results of the social validity questionnaire indicated that the mothers found the procedures easy to implement, were happy with the results, and would continue to use improvisation training. They also reported the use of correct improvisations outside the experimental sessions.

The results of the present study show a clear functional relation between parent-implemented training and improvisation of mands by children with autism. This supports the findings of Marckel et al. (2006), who demonstrated that children with autism can learn to improvise across symbol categories to mand for untrained preferred items. The present study also demonstrates that parents can effectively implement improvisation training.

To assess generalization prior to improvisation training, the experimenter conducted probe trials of untrained items during baseline. A limitation of this procedure was that, if the child used the correct descriptor card, he would have been provided access to the preferred item. This would have constituted a differential reinforcement procedure. For this reason, the generalization probes used during baseline may actually be considered a training procedure. However, it should be noted that neither child emitted any correct improvisations during the baseline generalization probes.

Another limitation of the study was that, due to technical difficulties or evidence of overt reactivity by the child, only about 85% of the sessions were videotaped. On the remaining sessions, live data were recorded. Because we were unable to record 15% of the sessions, we could not assess any of those sessions for interobserver agreement measures of children's responses or mothers' implementation. Another limitation was that there was not enough time to implement a maintenance phase. Future research would be enhanced by including data on maintenance of improvisation after the conclusion of training. This would provide important support for the long-term outcomes of parent-implemented interventions. Future research may also examine the extent to which teaching improvisation of mands affects emergent vocalizations and the function of those vocalizations. Systematic replication of the current procedures to other populations with language delays is also warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents and children who participated in this research. We also thank the West Virginia Autism Training Center for their support during the study.

Delia Ben Chaabane is now with the Mercer County Schools and Concord University.

REFERENCES

- Bondy A.S, Frost L.A. The picture exchange communication system. Focus on Autistic Behavior. 1994;9((3)):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon I.G, Iwata B.A. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marckel J.M, Neef N.A, Ferreri S.J. A preliminary analysis of teaching improvisation with the picture communication system to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:109–115. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.131-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]