Abstract

The effectiveness of a behavioral skills training (BST) package to teach the implementation of the first three phases of the picture exchange communication system (PECS) was evaluated with 3 adults who had no history teaching any functional communication system. A multiple baseline design across participants was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the training package, which consisted of a video, written and verbal instructions, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback. Results showed significant improvements relative to baseline in a short amount of training time and that skills generalized to a learner with a severe developmental disability. Skills were maintained at 1 month follow-up for 1 participant.

Keywords: behavioral skills training, picture exchange communication system

Behavioral skills training (BST) packages have been used to teach several behaviorally oriented skills and have been met with considerable success. For example, Iwata et al. (2000) implemented a BST system to teach undergraduate students to conduct functional analyses with confederate participants; Lavie and Sturmey (2002) taught teaching assistants to conduct paired-choice stimulus preference assessments; and Sarokoff and Sturmey (2004) taught special education teachers to conduct discrete trials (i.e., matching-to-sample tasks with two- and three-dimensional objects). Even though these studies demonstrated the effectiveness of BST packages to teach the implementation of several important skills, none of these studies assessed skill maintenance, and Iwata et al. did not test for skill generalization to actual clients. The purpose of the present investigation was to extend previous findings on the efficacy of BST by evaluating the effectiveness of a BST protocol in teaching the implementation of the first three phases of the picture exchange communication system (PECS; Frost & Bondy, 2002). Despite the growing popularity of this system, there are currently no empirical demonstrations of an effective training protocol to teach its implementation. The current study aimed to develop an innovative training package for individuals to learn the implementation of these skills in an effective and efficient manner that could also be evaluated empirically and replicated systematically. Participants were only taught skills consistent with the first three phases of PECS because prior research suggests that mastery of the first three phases is a worthwhile and realistic goal for many individuals with severe disabilities (e.g., Bondy & Frost, 1994; Chambers & Rehfeldt, 2003; Liddle, 2001; Rosales & Rehfeldt, 2007; Schwartz, Garfinkle, & Bauer, 1998).

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Two undergraduate students (Alexis and Priscilla) and 1 graduate student (Janet) in rehabilitation, who had no prior training in the implementation of any functional communication system, served as participants. Baseline, training, and testing sessions were conducted in a university clinic. Training sessions were conducted two or three times per week and lasted 45 to 90 min. Baseline and test sessions lasted 15 to 20 min. Generalization and maintenance probes were conducted in a quiet classroom in a local habilitation agency.

Confederate

An advanced undergraduate student skilled in PECS implementation served as the confederate learner during all baseline, training, and posttraining sessions. The experimenter provided the confederate with a list of responses likely to be emitted by a learner with a severe developmental disability during Phases 1 through 3 of PECS training (Table 1). These responses were rehearsed in several sessions prior to the study. The experimenter instructed the confederate to perform each of the described responses for each respective phase at least once per session.

Table 1.

Menu of Confederate Responses

| Phase | Responses |

| 1 | Pick up card and reach out to trainer |

| Hold hand out or try to reach for item without picking up card first | |

| Pick up card, but don't reach out to trainer | |

| Stare at picture on the table, but don't attempt to grab it | |

| Pick up card and reach out to trainer ONLY after she provides gestural prompt | |

| Pick up card and reach out to trainer ONLY after she provides physical prompt | |

| Pick up card and throw it to the trainer | |

| 2 | Pick up card, walk over to trainer and reach out with card in hand |

| Pick up card, but don't move towards trainer | |

| Walk directly to trainer without picking up card first | |

| Hold hand out or try to reach for item without picking up card first | |

| Stare at picture on the table, but don't attempt to grab it | |

| Pick up card and walk towards trainer ONLY after she provides gestural prompt | |

| Pick up card and walk towards trainer ONLY after she provides physical prompt | |

| Pick up card and throw it to trainer | |

| 3 | Select preferred item card and reach out to trainer to exchange picture |

| Select distracter card and reach out to trainer to exchange picture | |

| Select preferred item card and throw it to trainer | |

| Select distracter item card and throw it to trainer | |

| Select preferred item card ONLY after trainer goes through four-step correction procedure | |

| Select distracter item card again AFTER trainer goes through four-step correction procedure | |

| Stare at both pictures, but don't attempt to select either one | |

| Select distracter card and reach out to trainer to exchange picture, then immediately reach for preferred item picture after trainer provides access to distracter item |

Response Measurement and Experimental Design

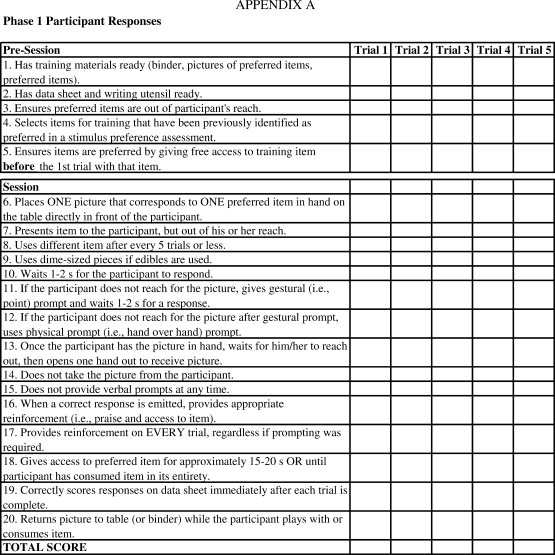

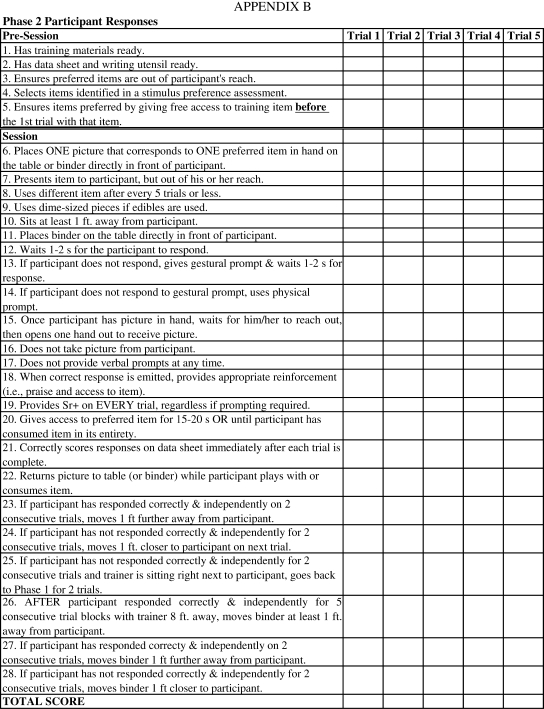

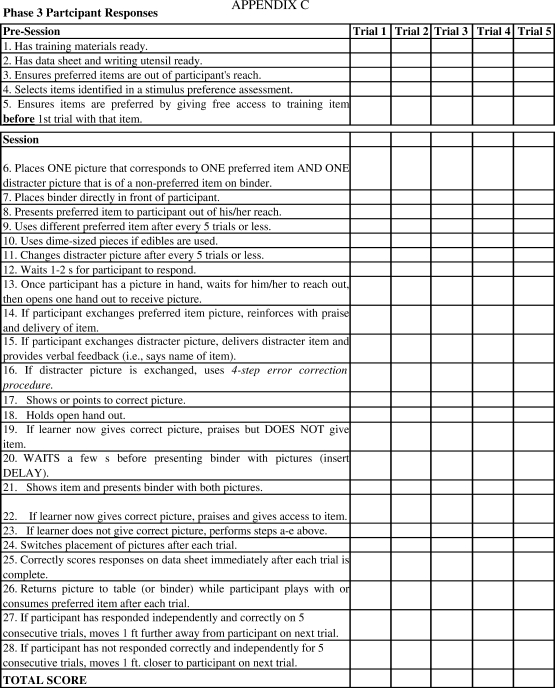

A multiple baseline design across participants was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the BST package. The primary dependent variable was the percentage of correctly performed responses on a checklist developed by the authors (presented in Appendixes A, B, and C) based on the PECS training manual (Frost & Bondy, 2002). This percentage was calculated by summing the total number of correctly preformed steps and dividing this number by the total possible responses in each five-trial block session. A correct response was defined as the participant exhibiting a behavior exactly as described on the checklist or not exhibiting a behavior if the step involved omission of a response (e.g., not providing verbal prompts). Steps on the checklist did not have to be performed in their exact order, with the exception of those steps that required the completion of a previous step in order to be executed (e.g., waiting 1 or 2 s for the confederate to respond before providing any prompts). If the participant implemented the step with any deviations from the description or exhibited a prohibited behavior, the observers scored the step as incorrect. A trial was defined as the completion of all possible steps of the procedure (see Appendixes A, B, and C) within a phase. Steps that were not applicable to a specific trial were marked N/A and omitted from the total possible responses (e.g., providing physical prompts may not have been necessary if a learner responded after a gestural prompt). Total training time for each phase was calculated for each participant. In addition, a multiple-choice quiz created for this study, based on information from the PECS training manual, was administered before and after training.

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement was examined on 33%, 37%, and 36% of all baseline, training, and test sessions for Janet, Alexis, and Priscilla, respectively, and was calculated by adding the number of agreements (the observers agreed that the participant performed the step correctly), dividing by the number of agreements plus disagreements (one observer scored correct and one observer scored incorrect performance of the step), and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean agreement was 95% (range, 88% to 98%) for Janet, 95% (range, 88% to 100%) for Alexis, and 91% (range, 77% to 100%) for Priscilla. Treatment integrity was also examined by having a second observer score correct and incorrect implementation of responses by the experimenter from checklists created for the purpose of this study (available from the third author). Treatment integrity was examined on 37% of all sessions, and mean integrity was 99.9% (range, 97% to 100%).

Procedure

Baseline and posttraining test sessions

Prior to baseline and training sessions, participants were given copies of the first 152 pages of the PECS manual. Prior to the first baseline session, participants were allowed 10 min to review these written materials before completing the 11-item written quiz. This quiz was administered once more to participants following completion of training and prior to posttraining test sessions. After administration of the quiz, participants were provided with all of the necessary materials for Phases 1 through 3 of PECS. Participants were instructed to conduct one five-trial block of each phase with the confederate learner. No feedback was delivered. Posttraining sessions were identical to baseline test sessions, with the exception that participants were instructed to conduct three five-trial blocks of each phase with the confederate learner. Posttraining sessions were conducted after the participant had completed training and met criterion in all three phases of PECS.

BST

Prior to the initial training session only, participants viewed the complete 26-min video created by the authors of the PECS manual (Frost & Bondy, 1998). Participants also viewed a 15-min video segment of a real training session of Phase 3 of PECS that involved a proficient graduate student and an adult with a severe developmental disability. Prior to training in each phase, participants were provided with the appropriate checklist, which the trainer verbally described step by step. Participants were allowed to keep copies of each checklist, but were not specifically instructed to review them at any time. After verbally describing each checklist item, the trainer and confederate learner modeled each step in one five-trial block. The trainer conducted as many trial blocks as necessary to model all possible checklist steps and responses at least once. Participants were then instructed to conduct one five-trial training block with the confederate learner, which was followed by corrective or approving feedback provided by the experimenter. Modeling, rehearsal, and feedback components of the BST package were repeated until participants performed correctly on 80% of all steps over two consecutive trial blocks. If no corrective feedback was necessary on any trial block, the experimenter provided positive feedback but did not repeat the modeling component of the BST package. Participants were given the opportunity to rehearse all of the responses on each checklist at least once before moving on to the next phase of training. Because many of the responses were not applicable until the learner responded correctly after multiple consecutive trials (i.e., move the binder away during Phase 2), multiple trial blocks were sometimes necessary to score participants on all of the relevant responses for each phase.

Generalization probes

Generalization probes were identical to baseline and posttraining test probes, with the exception that an adult with a severe developmental disability who had limited functional communication skills served as the learner. Sessions were conducted at that individual's habilitation facility.

Maintenance probes

Maintenance probes were identical to posttest and generalization probes, with the exception that a second adult with a severe developmental disability and limited functional communication skills served as the learner. Maintenance probes were also conducted in the clinic setting with the confederate learner and were conducted only with Janet because both Alexis and Priscilla had begun implementation of PECS for practicum experience and were receiving on-site instruction.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

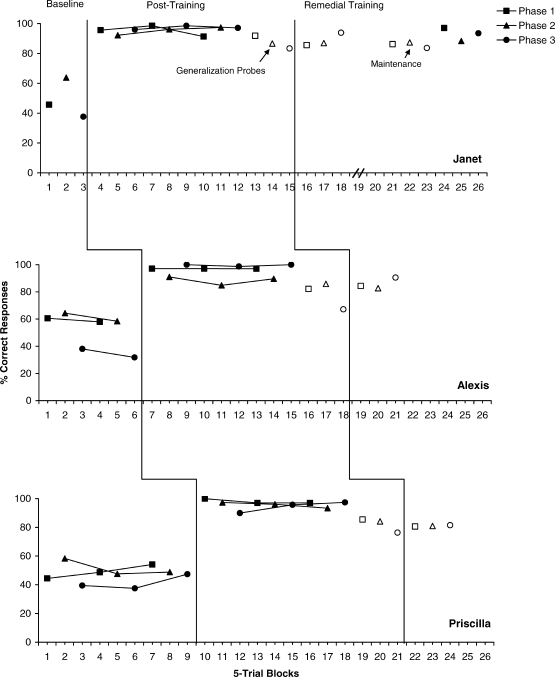

Figure 1 shows the percentage of correct responses for each phase of PECS during baseline, posttraining, generalization, and maintenance test probes conducted in five-trial blocks. It also illustrates that none of the participants demonstrated criterion performance during baseline for any of the three training phases. However, all participants did meet criterion on posttraining probes, showing significant improvements relative to baseline. Mastery criterion was demonstrated by all participants in all phases after two five-trial blocks. However, multiple trials were conducted during training for all phases and all participants (except Janet during Phase 1) to provide them with additional opportunities to perfect the checklist responses or to allow them to practice all responses at least once. Results of an error analysis suggested that one step consistently missed across participants and phases was for the trainer to open one hand to receive the picture from the learner. In addition, during Phase 2, all participants consistently missed the steps instructing them to move further away from or closer to the learner contingent on the learner's responses. Participants may have benefited from additional training on these steps.

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct responses in five-trial blocks on checklists for Phases 1 through 3 during baseline, posttraining, and generalization probes.

Total training times were 131 min for Janet, 199 min for Alexis, and 208 min for Priscilla. All participants demonstrated the generalization of skills consistent with Phases 1 through 3 of PECS during test probes conducted with a novel learner in a novel setting, although initial scores (Figure 1) were not as high as scores on the final posttraining test trials. As a result, remedial training was conducted after the first set of generalization probes and consisted of each participant returning to the university clinic with the trainer and confederate learner to review each checklist. Participants were provided with another five-trial model by the experimenter and were given the opportunity to rehearse each phase in one to three five-trial blocks per phase. This resulted in generalization test scores at or above mastery criterion for all participants in all phases. Janet was shown to maintain skills 1 month posttraining when both the confederate and an individual with severe developmental disabilities served as the learners.

Quiz scores showed improvement from pre- to posttraining administration for Janet and Priscilla, but not for Alexis. These results suggest the potential ineffectiveness of written materials when used as a primary component of staff training.

This study extends previous research by providing evidence for the generalization of skills to a learner with a severe developmental disability and indicates that maintenance of those skills is possible. In addition, an innovative training package was designed to be systematically replicated by other professionals faced with the task of training individuals who have limited experience working with people who have severe disabilities. This training package will help trainers to implement PECS in an effective and efficient manner.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Specialized Training and Adult Rehabilitation (START) in Murphysboro, Illinois, for support of this project. We also thank Chris Ninness and four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bondy A.S, Frost L.A. The picture exchange communication system. Focus on Autistic Behavior. 1994;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers M, Rehfeldt R.A. Assessing the acquisition and generalization of two mand forms with adults with severe developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2003;24:265–280. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(03)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost L, Bondy A. The picture exchange communication system training manual. Newark, DE: Pyramid Educational Products; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frost L, Bondy A. (Producers) An introduction to PECS: Picture exchange communication system [Motion picture] 1998. (Available from Pyramid Educational Consultants, Inc., 226 W. Park Place, Suite 1, Newark, DE 19711)

- Iwata B.A, Wallace M.D, Khang S.W, Lindberg J.S, Roscoe E.M, Conners J, et al. Skill acquisition in the implementation of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:181–194. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie T, Sturmey P. Training staff to conduct a paired-stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:209–211. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle K. Implementing the picture exchange communication system (PECS) International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2001;36:391–395. doi: 10.3109/13682820109177917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Rehfeldt R.A. Contriving transitive conditioned establishing operations to establish derived manding skills in adults with severe developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:105–121. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.117-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarokoff R.A, Sturmey P. The effects of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:535–538. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz I.S, Garfinkle A.N, Bauer J. The picture exchange communication system: Communicative outcomes for young children with disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1998;18:144–159. [Google Scholar]