Abstract

The small G-protein KRAS is crucial for mediating gonadotropin-induced events associated with ovulation. However, constitutive expression of KrasG12D in granulosa cells disrupted normal follicle development leading to the persistence of abnormal follicle-like structures containing non-mitotic cells. To determine what factors mediate this potent effect of KrasG12D, gene profiling analyses were done. We also analyzed KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre and KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mutant mouse models that express Cre prior to or after the initiation of granulosa cell differentiation, respectively. KrasG12D induced cell cycle arrest in granulosa cells of the KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice but not in the KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice, documenting the cell context specific effect of KrasG12D. Expression of KrasG12D silenced the Kras gene, reduced cell cycle activator genes and impaired expression of granulosa cell and oocyte specific genes. Conversely, levels of PTEN and phosphorylated p38MAPK increased markedly in the mutant granulosa cells. Because disrupting Pten in granulosa cells leads to increased proliferation and survival, Pten was disrupted in the KrasG12D mutant mice. The Pten/Kras mutant mice were infertile but lacked granulosa cell tumors. By contrast, the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice developed aggressive ovarian surface epithelial (OSE) cell tumors that did not occur in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre or Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mouse strains. These data document unequivocally that Amhr2-Cre is expressed in and mediates allelic recombination of oncogenic genes in OSE cells. That KrasG12D/Pten mutant granulosa cells do not transform but rather undergo cell cycle arrest indicates that they resist the oncogenic insults of Kras/Pten by robust self-protecting mechanisms that silence the Kras gene and elevate PTEN and phospho-p38MAPK.

Keywords: ovary, granulosa cell, Kras, Pten, oncogenes, ovarian cancer, follicle development

Introduction

Ovarian cancer represents a major threat to women's health because our knowledge of the underlying causes of this complex and heterogeneous disease remains ill defined. Ovarian carcinomas of the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) are the most aggressive and prevalent, accounting for ∼90% of all human epithelial ovarian cancers and have been classified based on histological criteria as serous, endometrioid, clear cell and mucinous. By contrast, only 5% of human ovarian cancers are derived from granulosa cells (1-3). This seems unexpected because granulosa cells are the most abundant proliferative cell type in the ovary. It is not known if the low incidence of granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) is due to the strong resistance of granulosa cells to oncogenic stimuli, the rare occurrence of oncogenic mutations in this population of ovarian cells or to the natural fate of granulosa cells that are removed from the proliferative stage either by apoptosis or the natural progression to terminally differentiated non-dividing luteal cells.

The proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells in developing follicles are regulated by the pituitary gonadotropins follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) and their G-protein coupled receptors as well as by ovarian derived growth regulatory factors (4, 5). Recent studies document that in addition to the canonical cAMP/protein kinase A pathway, FSH and LH activate several other signaling cascades, such as the RAF1/MEK/MAPK3/1 (also known as ERK1/2) pathway and the PI3K/AKT pathway (6-9) via activation of the small G-protein RAS and the tyrosine kinase SRC, respectively (7). Conditional expression of an oncogenic KrasG12D mutation in granulosa cells impacts both the ERK1/2 and PI3K pathways and leads to defects in follicle development and ovulation (10). Surprisingly, whereas KrasG12D mutations induce tumors in lung (11), mammary gland (12) and uterus (Wang J and DeMayo F, unpublished results), it does not stimulate the oncogenic transformation of granulosa cells. Rather, the KrasG12D expressing granulosa cells undergo cell cycle arrest, are non-mitotic based on the absence of either BrdU labeling or phospho-histone H3 immuno-staining, are non-apoptotic based on the lack of TUNEL positive cells or cells exhibiting cleaved caspase 3 immuno-staining and fail to differentiate 10. The abnormal follicle-like structures are devoid of oocytes and persist in the mutant ovaries for prolonged periods of time (10).

The PI3K pathway is well recognized as essential for cell survival and proliferation; its hyper-activation is associated with oncogenesis in multiple tissue and cell types (13, 14). The phosphatidylinositol phosphate phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase tensin homolog) negatively regulates the activity of PI3K pathway and therefore functions as a potent tumor repressor. Although mutations of the Pten locus can lead to tumor formation in many but not all tissues (15, 16), the disruption of the Pten gene causes embryonic lethality in mice, indicating that it is also essential for normal development (17). Selective depletion of Pten in mouse granulosa cells leads to hyper-activation of the PI3K pathway, increased follicle growth and ovulation, and the prolonged life-span of corpora lutea (18) but rarely induces GCTs (19).

In this study, we sought to determine the cell specific and combinatorial effects of expressing KrasG12D and mutant Pten in mouse ovarian cells. Using six different mouse models we document that the KrasG12D mutation in granulosa cells induces cell cycle arrest in a developmental stage-dependent manner and that mice with double mutations of Pten/Kras selectively in granulosa cells were infertile but showed no GCTs. By contrast, in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2Cre mice where double mutations are expressed in granuloss cells and the OSE (OSE) cells, massive ovarian serous papillary adenocarcinomas develop at an early age. These results indicate that granulosa cells are highly resistant to these oncogenic factors that transform OSE cells and therefore possess robust self-protecting mechanisms that arrest cell cycle progression.

Materials and Methods

Animals

LSL-KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre, Ptenfl/fl;LSL-KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre, Ptenfl/fl;LSL-KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre and Ptenfl/fl;LSL-KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice were derived from previously described Amhr2-Cre, Cyp19-Cre, Pgr-Cre, Ptenfl/fl and LSL-K-rasG12D parental strains, and genotyping was done by PCR as described (10, 20-23). Histological images and the efficient recombination of the mutant alleles was documented for each genotype (Suppl. Fig. 2G). Animals were housed under a 16-h light/8-h dark schedule in the Center for Comparative Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and provided food and water ad libitum. Animals were treated in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

Immature 21 day-old female mice were injected intraperitoneally (ip) with 4IU of eCG (equine chorionic gonadotropin; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) to stimulate follicular growth followed 48h later with 5IU hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin, American Pharmaceutical Partners, Schaumburg, IL) to stimulate ovulation and luteinization. Ovulated oocytes were collected from oviducts 16h after hCG injection. Development of ovarian tumors was checked in mice at the age of 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Ovaries were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and embedded in paraffin and processed by routine procdures (10). Immunohistochemistry was done as previously described 10 using antibodies against cytokeratin 8 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), PTEN (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or PCNA (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted.

Immunofluorescence

Ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA, embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek USA Inc.) and stored at -70°C before the preparation of 7μM sections and immunostaining (10). Antibodies for WT1, KRAS, Cyclin A and E2F1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA. All the other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. The MUC16 antibody was gifted from Dr. Robert Bast, Jr.

BrdU incorporation assay

BrdU and a monoclonal antibody against BrdU (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) were used as previously described (10).

Hormone assays

Radioimmunoassays for FSH and estradiol were performed by the Ligand Assay and Analysis Core, SCCPIR (University of Virginia), as previously described (24).

Microarray analyses

Total ovarian RNA was isolated from 3-month-old KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice and immature 26 day old control mice using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD). At 3 months of age, 100% of the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre ovaries contain an abundance of abnormal follicles but not corpora lutea whereas the immature mouse ovaries contain predominantly normal follicles. Thus, this was deemed the most appropriate comparison for detecting granulosa cell genes. To avoid ovarian related differences in gene expression that could arise by comparing single ovaries, RNA samples from 3 animals per genotype were pooled before microarray probe synthesis. Wild type and KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre riboprobes were then hybridized to Mouse 430.2 microarray chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). All steps of RNA quality control, probe synthesis, hybridization, washing, array scanning, and statistical analyses were done by the Microarray Core Facility of the Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX) as previously described (25).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

For real-time RT-PCR analyses additional total ovarian RNA was also isolated from ovaries of control (26 day and 3 month old) mice, KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre (3month old) mice and Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre (3 month old) mice. Reverse transcription was done using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR system with Platinum Taq kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The real-time PCR was performed using the Rotor-Gene 3000 thermocycler (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia). The PCR reaction included 5 μl of SYBR Green JumpStart Taq Mix (Sigma), 4.0μl first strand cDNA product described above (1:100 dilution), and 0.5μM of forward and reverse primers. Relative levels of gene expression were calculated using Rotor-Gene 6.0 software and normalized to beta-actin.

Western Blot Analysis

Tissues and cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche)(10). Western blots were performed utilizing 30μg of lysate protein, incubated with antibodies specific for: FOXO1, FOXO3, PTEN, AKT, cyclin D2 and phospho-mTOR, -GSK3β, -PDK1, -ERK1/2, -AKT, (all from Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), cyclin A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), E2F1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Statistical analyses

The data for real-time RT-PCR assays, breeding experiments, hormone levels and super-ovulation tests are represented as means ± SD. Data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism Programs (ANOVA or t test; GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA) to determine significance. Values were considered significantly different if P≤0.05 or P≤0.01.

Results

KrasG12D induction of cell cycle arrest in ovarian granulosa cells is stage-dependent

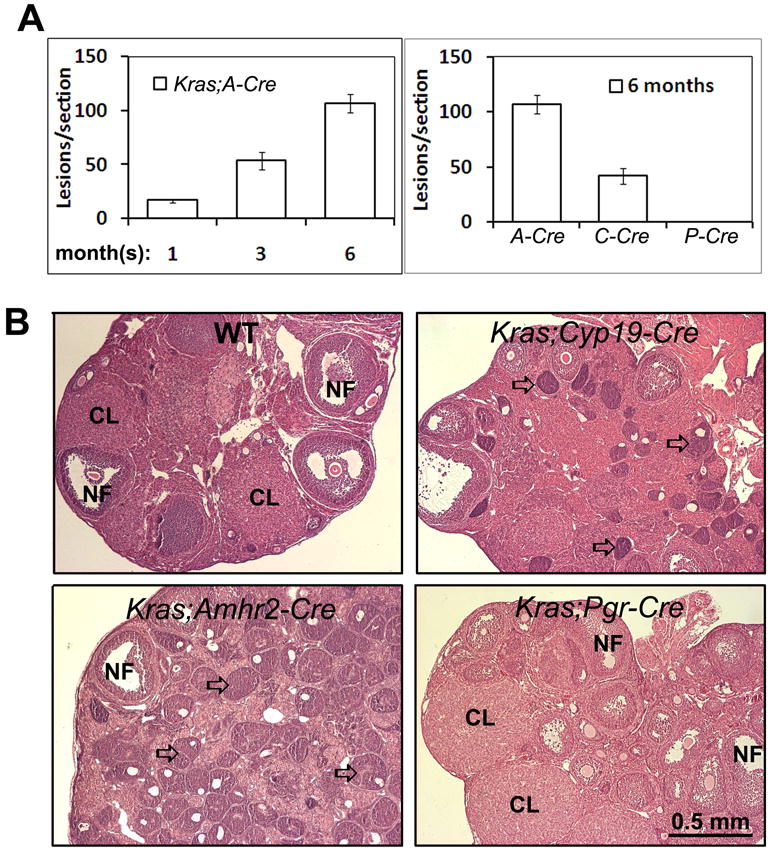

The KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mutant mice contain abnormal follicle-like structures consisting of non-mitotic and non-apoptotic granulosa cells that persist for prolonged periods of time (10). As shown herein, the ovaries of KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice progressively increase in size as the mice age and this is associated with the accumulation of the small follicle-derived ovarian lesions (Fig. 1A, for each time point or genotype, ovaries from at least 4 animals were sectioned, and ovarian lesions were counted in 6 sections of each ovary). To determine if the formation of these abnormal follicle-like structures was dependent on the stage of granulosa cell differentiation, we generated three KrasG12D mutant mouse models using mouse strains (Amhr2-Cre, Cyp19-Cre and Pgr-Cre) in which Cre is driven by promoters expressed at different stages of follicular development in vivo. In the Amhr2-Cre and Cyp19-Cre females, Cre-mediated allelic recombination occurs primarily in proliferating granulosa cells of primary follicles and early antral follicles, respectively. Because the expression of the endogenous progesterone receptor (Pgr) gene is induced only in granulosa cells of preovulatory follicles exposed to the LH surge, Cre-mediated allelic recombination in the Pgr-Cre mice is restricted to terminally differentiating granulosa cells undergoing luteinization (Fig. 1B) (23, 26). When the ovaries of the three mutant mouse models were compared at 6 months of age, the ovaries of KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre females contained 2-fold more abnormal follicle-like structures than those of the KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (Fig. 1A). Strikingly, ovaries of the KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre females contained no abnormal follicle-like structures and were normal (Fig. 1B), indicating that the KrasG12D mutation initiates inappropriate cell cycle arrest only at an early stage of follicle development when granulosa cells are proliferating.

Figure 1. KrasG12D selectively impacts granulosa cell function in mice expressing Cre driven by the Amhr2 (A-Cre) and Cyp19 (C-Cre) but not Pgr (P-Cre) promoters.

Ovaries of KrasG12D;A-Cre mice accumulate more small abnormal follicle-like lesions (arrows) from 1-6 months of age than did the KrasG12D;C-Cre mice (A &B). No abnormal follicles were observed in ovaries of the KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice. NF: Normal follicles; CL: corpora luteum.

KrasG12D alters cell cycle and differentiation related gene expression profiles in granulosa cells

Gene expression profiling (Suppl. Table 1) and real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 3B) using total RNA from ovaries of KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice documented that genes regulating cell cycle progression (27), especially cyclins and members of the E2F transcription factor family, were down-regulated whereas the genes, Pten and Zbtb16 (also known as Plzf) that have been reported to repress cell cycle progression (28), were up-regulated (Suppl. Table 1, Fig. 3B). Genes that control granulosa cell differentiation [FSH receptor (Fshr), activin/inhibin (Inhba/Inhbb/Inha) and aromatase (Cyp19)] and genes encoding key transcription factors Fos, Foxo1 and Nr5a2 were down-regulated in the KrasG12D mutant cells (Suppl. Table 1). By contrast, expression levels of the LH receptor (Lhcgr) and the cholesterol side chain cleavage cytochrome P450 enzyme (Cyp11a1) increased and are likely associated with the hypertrophy of interstitial cells in the Kras mutant ovaries.

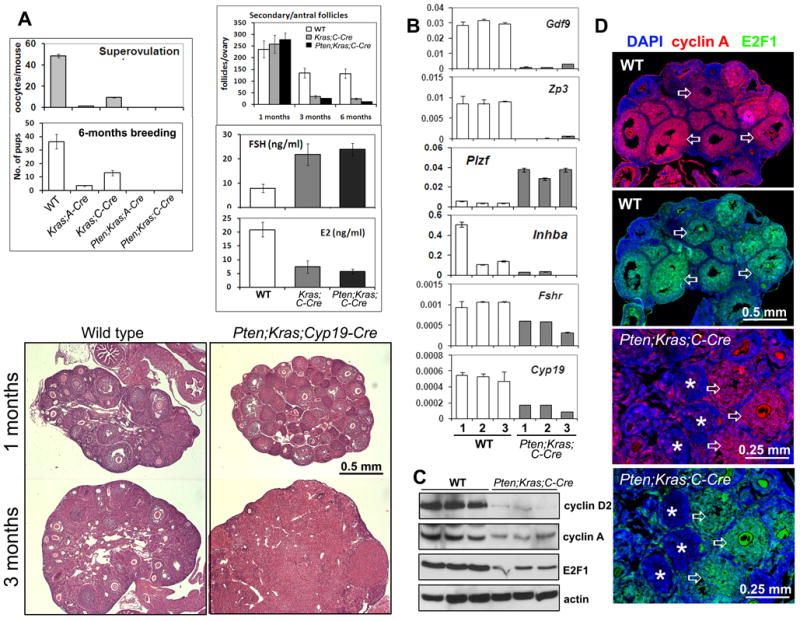

Figure 3. Pten/Kras double mutant mice exhibit signs of premature ovarian failure (POF).

Fertility of females in the various mouse strains was evaluated by super-ovulation and breeding assays (A). Kras and Pten/Kras double mutant mice have reduced numbers of ovarian follicles, high serum FSH and low serum estradiol, symptoms of POF (A). H&E staining of ovarian sections confirmed the altered ovarian phenotype of Pten/Kras mutant mice at 1 and 3 months of age (A). Genes crucial for oocyte function and follicle development were down-regulated in Pten/Kras double mutant ovaries compared to wild-type at 3 months of age (B). Cell cycle regulators were decreased in Pten/Kras double mutant ovaries (C). Cyclin A (red) and E2F1 (green) are highly expressed in granulosa cells present in growing follicles (arrows) in wildtype (WT) and Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice, but not in cells present in abnormal follicles (asterisks) of 1 month old Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (D).

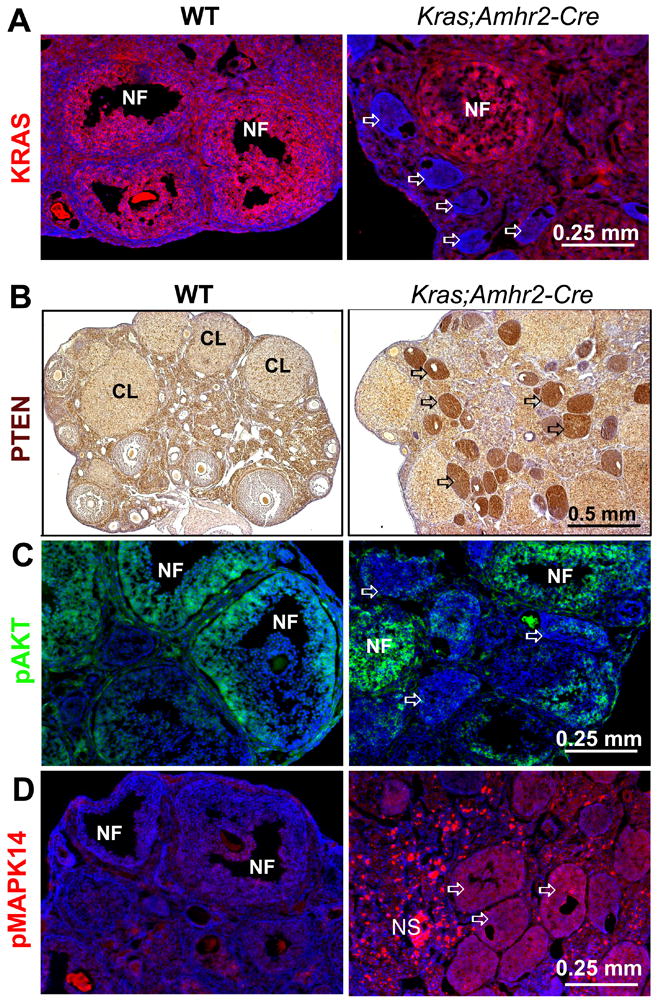

KrasG12D mediated cell cycle arrest in ovarian granulosa cells is associated with elevated PTEN and phosphorylated p38MAPK and reduced expression of KRAS

KRAS is highly expressed in granulosa cells of normal growing follicles (Fig. 2A WT), but was undetectable in the non-mitotic granulosa cells within the abnormal follicles (Fig. 2A: Kras;Amhr2-Cre). Moreover, the response of granulosa cells to KRASG12D is dependent on the level of the mutant the KRAS expressed in these cells (Suppl. Fig. 1A-C) supporting the evidence that p15INK4B, p16INK4A and TRP53 are unlikely to mediate the effects of KRASG12D in granulosa cells of the Kras;Amhr2-Cre mice in vivo.

Figure 2. KrasG12D down-regulates KRAS and up-regulates PTEN in the follicle-like lesions.

Granulosa cells of normal growing follicles express KRAS whereas KRAS was negligible in cells within the abnormal follicles (A, arrows). NF: normal follicles. PTEN levels were low in granulosa cells of normal follicles but were elevated in the mutant granulosa cells (B, arrows) and this was associated with reduced levels of phospho-AKT (wild type versus KrasG12D;A-Cre: (C) but high levels of pMAPK (phospho-p38MAPK) (D).

Because the microarray results indicated that Pten mRNA levels increased in the Kras mutant ovaries, the cell specific expression of PTEN protein was analyzed and shown to be low in granulosa cells of the growing follicles present in ovaries of control mice compared to interstitial cells and corpora lutea (Fig. 2B, WT) (18). In marked contrast, PTEN was dramatically elevated in cells within the follicle lesions present in ovaries of the Kras mutant mice (Fig. 2B, Kras;Amhr2-Cre; Supp. Fig. 4). Elevated PTEN in the mutant granulosa cells was associated with negligible immuno-staining for phospho-AKT compared to granulosa cells in normal growing follicles (Fig. 2C). In contrast to the suppression of the KRAS-ERK1/2 and AKT pathways in the KrasG12D mutant granulosa cells, elevated levels of phospho-p38MAPK (pMAPK14) were observed in these cells (Fig. 2C). Although phospho-p38MAPK is commonly associated with oncogenic-induced cell cycle arrest and senescence in fibroblasts and epithelial cells (29, 30), the KrasG12D mutant granulosa cells did not express (SA)-beta-galactosidase (31) or the secretory factor, IL6 (32)(data not shown). Thus, the complete silencing of the Kras gene (Fig. 2A) and down-regulation of the cell cycle regulatory molecules (Suppl. Table 1) combined with up-regulation of PTEN and phospho-p38MAPK appear to characterize the phenotype in the cycle arrested granulosa cells.

Double mutations of Pten and Kras in granulosa cells do not lead to tumors but do disrupt ovarian function and fertility leading to premature ovarian failure

Because disrupting Pten alone in ovarian granulosa cells in the Ptenfl/fl;Cyp19-Cre mice increases fertility and leads to the extended survival and life-span of granulosa/luteal cells (18) and only rarely leads to GCTs in the Ptenfl/fl;Amhr2-Cre mice (19), we next sought to determine if disrupting Pten in the Kras mutant genotypes would lead to tumor formation. Contrary to our hypothesis, double mutations of Pten and Kras in granulosa cells of the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre and KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice failed to cause the development of GCTs but altered follicular growth, prevented ovulation and rendered the mice infertile (Fig. 3A), a phenotype more severe than that of the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre and KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre females (10). These results indicate that the Kras mutation plays a dominant role in granulosa cells and that the conditional knockout of Pten strengthened the effect of KrasG12D.

Histopathological examination of ovarian morphology indicated that the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre double mutant mice showed signs of premature ovarian failure. Ovaries from females older than 3 months had reduced numbers of developing follicles (Fig. 3A), high levels of serum FSH and low levels of serum estradiol (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, granulosa cell marker genes and oocyte-specific genes were dramatically decreased in Kras mutant ovaries (Suppl. Table 1, Fig. 3B).

Western blot and immunofluorescent analyses show that cyclin D2, cyclin A, and E2F1 are highly expressed in granulosa cells of wild type mice but are markedly reduced in ovaries of 3 month old Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (Fig. 3C-D and data not shown). Immuno-staining of cyclin A and E2F1 was negligible in granulosa cells present in the abnormal follicle-like structures compared to the normal-looking follicles in the 1-month-old Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre ovaries (Fig. 3D).

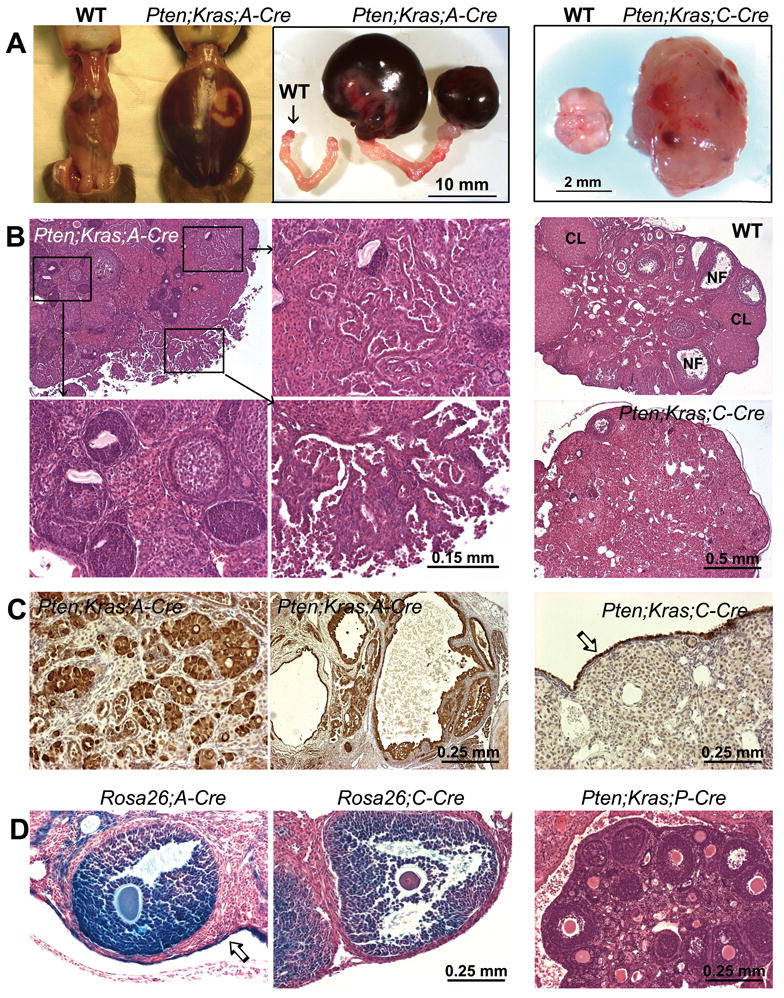

Double mutations of Pten and Kras in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice but not the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice cause OSE cancer

Although GCTs did not develop in response to double mutations in KrasG12D and Pten, the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) was affected selectively when recombination of both genes was driven by Amhr2-Cre. The Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice developed aggressive OSE tumors as early as 1 month of age (Fig. 4A/B: Pten;Kras;A-Cre) whereas the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre females did not. (Fig. 4A/B: Pten;Kras;C-Cre; Suppl. Fig. 2). The ovarian tumors present in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice have been classified as low grade serous papillary cystadenocarcinomas by histological criteria (Fig. 4; Suppl. Fig. 2&3) and by immuno-staining of ovarian sections with the epithelial cell marker cytokeratin 8 (CK8) (Fig. 4C), the OSE cell marker MUC 16 and the serous adenocarcinoma cell marker WT-1 (Suppl. Fig. 3A-C). The development of OSE cell tumors in the Amhr2-Cre mouse strain but not the Cyp19-Cre strain is caused by the expression of Amhr2-Cre recombinase in OSE cells, as demonstrated by LacZ staining of OSE cells in the Rosa26;Amhr2-Cre but not in the Rosa26;Cyp19-Cre reporter mouse strains (Fig. 4D). These results extend those of Connolly et al who generated OSE tumors using the Amhr2 promoter to direct expression of the SV40 TAg (33) and Szotek et al who reported that cell lines derived from mouse ovarian epithelial cell tumors express AMHR2 (34). Furthermore, when the double mutations were made in the Pgr-Cre mouse strain, ovaries of the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre females showed relatively normal histology and were devoid of both the follicle-derived ovarian lesions and OSE cell tumors (Fig. 4D: Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre; right panel) despite the fact that they develop massive uterine tumors and die within 6 weeks after birth (Wang J and DeMayo F, unpublished data).

Figure 4. OSE (OSE) cell cancers develop in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice but NOT in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice or Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice.

Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre female mice develop massive low grade serous, papillary cystadenocarcinomas by 3 months of age (A - C). Multifocally the cystadenocarcinoma invades the ovarian parenchyma (Panel B, upper right) and surround the abnormal follicle-like structures (Panel B; lower left). Ovaries of the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice are larger ovaries than wild type mice due to the hyperplasia of interstitial tissue, but do not develop ovarian tumors (Panels A-C; right). The epithelial cell origin of tumors was confirmed by immuno-staining of cytokeratin 8 (CK8) in wild-type and Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (Panel C; right) and in tumor structures invading the ovary (Panel C; left) as well as in tumor-derived cysts (Panel C; middle). LacZ- staining in Rosa26 reporter mouse strains showing localization to granulosa cells in Cyp19-Cre mice (D; middle panel) and to OSE cells in Amhr2-Cre mice (D; left panel). Ovaries from a 5 week old Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice have no abnormal follicle-like lesions and no OSE tumors (D; right panel), despite the development of massive uterine tumors (data not shown).

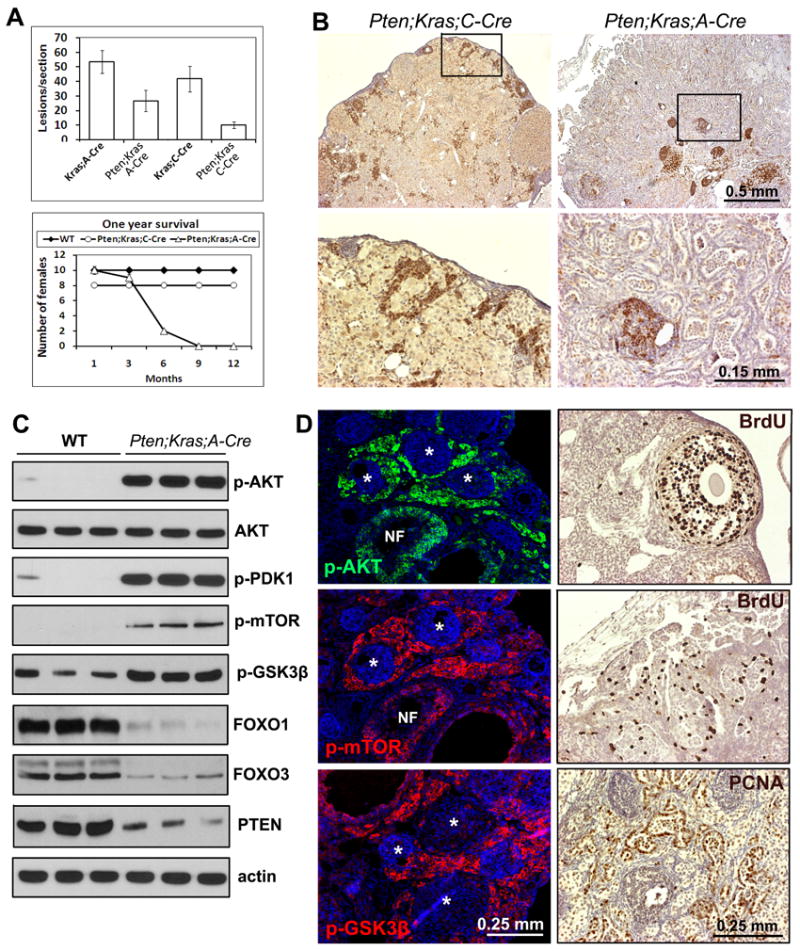

Due to the expansive growth of OSE cell tumors in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre females, they die between 3-6 months of age (Fig. 5A). In contrast, mice with single mutations of Pten (Ptenfl/fl;Amhr2-Cre) were viable (18) and rarely developed GCTs (19) whereas the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre and Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre females were viable without signs of ovarian tumor development (Fig. 5A), although some OSE cell hyperplasia was observed in the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre females at 10 months or older (data not shown). The abnormal follicle-derived ovarian lesions induced by KrasG12D were observed in the Pten/Kras double mutant ovaries but the number decreased dramatically (Fig. 5B), suggesting PTEN activity is required to maintain these structures.

Figure 5. The PI3K pathway is hyper-activated in Pten/Kras-induced OSEtumors.

Conditional depletion of Pten in granulosa cells reduced the numbers of ovarian lesions in ovaries of both Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice and Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (A). Most Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice died of ovarian cancers between 3-6 months of age (A). PTEN was expressed in the ovarian stroma of Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice (B) but was absent in OSE tumor cells of Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice (B). Western blot analyses (C) and immunofluorescent staining (D; left panels) of PI3K pathway components in OSE cells. BrdU is incorporated into proliferating granulosa cells in normal (WT) ovaries (D; upper right panel) and the OSE tumor cells in Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice (D; middle right panel). The OSE tumor cells also stained for PCNA (D; lower right panel).

PI3K pathway is hyper-activated in Pten/KrasG12D-induced OSE tumors

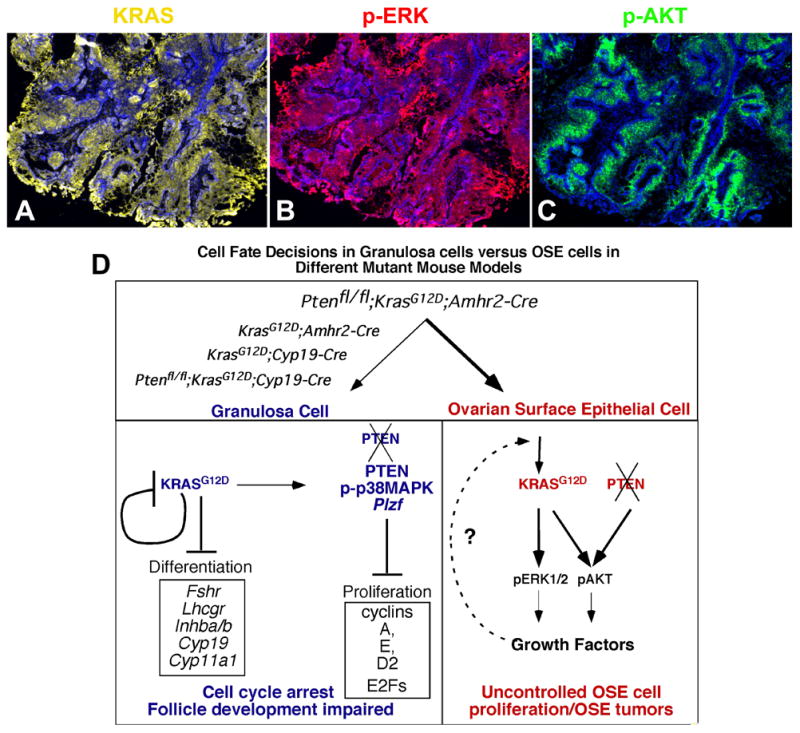

PTEN was expressed in the stromal cells and remnants of abnormal follicle-like structures present in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre ovaries (Fig. 5B). By contrast, the OSE tumor cells present in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre ovaries were completely devoid of PTEN (Fig. 5B) compared to the control OSE cells (Suppl. Fig. 4) and showed elevated activity of the PI3K pathway components compared with wild type controls (Fig. 5C) presumably due to the increased AKT activity (Fig. 5D). Immunofluorescent staining of ovaries from 1 month old Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice showed that AKT and its target kinases mTOR and GSK3β are highly phosphorylated in the invading OSE tumor cells, but not in the non-mitotic granulosa cells (Fig. 5D). The OSE tumor cells showed active proliferation, based on the incorporation of BrdU (Fig. 5D) and immuno-staining of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Fig. 5D). Strikingly, while expression of KRAS was silenced in granulosa cells of the KrasG12D-induced abnormal follicles (Fig 2A), KRAS was high in OSE tumor cells and were associated with high levels of phospho-ERK1/2 and phospho-AKT but not phospho-p38MAPK (Fig. 6A-C; Suppl. Fig. 3D). The inability of OSE cells to inactivate RAS-related signaling events under oncogenic insults may explain why these cells but not granulosa cells are susceptible to tumorigenic stimuli.

Figure 6. KRAS-related signaling pathways are actively involved in the development of OSEcancers.

KRAS is highly expressed by OSE tumor cells of Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice (A) and this is associated with elevated levels of phospho- ERK1/2 (B) and phospho-AKT (C). The cell and stage specific effects of Kras/Pten mutations on OSE cells and granulosa cells were summarized schematically (D).

Discussion

We document for the first time that the effects of expressing KRASG12D in ovarian granulosa cells in vivo are dependent on the stage of granulosa cell differentiation. In proliferating granulosa cells present in small growing follicles of the KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice and KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice, the expression of KRASG12D led to cell cycle arrest and the absence of genes associated with a differentiated granulosa cell phenotype. As a consequence these mice become infertile. However, in the KrasG12D;Pgr-Cre mice where the expression of KRASG12D only occurs in differentiating granulosa of preovulatory follicles after the LH/hCG surge, we observed no overt effects on ovarian function and the mice remained fertile. The consequences of depleting Pten in cells expressing KRASG12D were also cell type specific. Whereas Kras/Pten mutant granulosa cells did not exhibit signs of increased proliferation or transformation, OSE cells challenged with the same genetic alterations exhibited serous papillary cystadenocarcinomas within one month of age. These results document unequivocally that the impact of mutant KRASG12D and Pten depletion are cell type specific within the ovary and that granulosa cells, like some other mitotic cells (31, 35), possess mechanisms to combat oncogenesis by entering cell cycle arrest (Fig. 6D).

Specifically, our results document in six mutant mouse in vivo models that KRASG12D potently impacts the proliferative capacity of granulosa cells. If recombination occurs in granulosa cells of small growing follicles, these cells become non-mitotic 10 and express extremely low levels of genes and proteins related to cell cycle progression, especially factors regulating entry into S-phase of the cell cycle (27, 36) including cyclin A, cyclin D2, and E2F1. Whereas cyclin A and cyclin D2 regulate specific cell cycle dependent kinases, E2F1 regulates the transcription of cyclin A and other transcriptional co-regulators that mediate entry into the S phase (27). Because activin can impact granulosa cell proliferation (37, 38) and has been linked to ovarian stromal tumors (39), it may be important that levels of Inhba and Inhbb are negligible in the KrasG12D mutant cells. That the small abnormal follicle-like structures persist and accumulate in the ovaries of the mutant mice is associated with, and may be dependent on the lack of apoptosis as well as cell cycle arrest (10).

The mechanisms regulating cell cycle arrest in the granulosa cells may to be mediated, in part, by the silencing of the Kras gene, thus impairing the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT. Although KrasG12D is expressed at the time of recombination (10), the complete absence of KRAS protein in the mutant granulosa cells suggests that KrasG12D silences the Kras gene. To our knowledge, the silencing of the Kras gene by oncogenic KRASG12D has not been reported previously, may represent an E2F1 mediated regulatory mechanism (35) and appears to be independent of factors implicated in regulating cell cycle arrest and senescence in other cell types (31, 40, 41) (Suppl. Fig. 1 and 2). That silencing the Kras gene is critical for preventing granulosa cell tumor formation is supported by the observations that the Ptenfl/fl;Ctnnb1exon3fl/-; Amhr2-Cre mice expressing constitutively active beta-catenin (CTNNB1) in the Pten null background develop metastatic GCTs with 100% penetrance at an early age (19). Thus, the response of granulosa cells to oncogenic factors depends on which combinations of oncogenic stimuli are expressed in these cells.

Additional mechanisms controlling cell cycle arrest in the Kras mutant granulosa cells appear to be associated with and perhaps mediated by elevated levels of the tumor suppressor PTEN, phospho-p38MAPK mediated events and/or the repressor of transcription Zbtb16 (Plzf), all of which are increased in the KrasG12D mutant cells. Because PLZF is a potent regulator of germ cell stem cell survival (28, 42) and has been linked to cell senescence (43), it may participate in the extended life span and lack of differentiation of these somatic granulosa cells. That phospho-p38MAPK is elevated markedly in the non-mitotic granulosa cells may be important, because phospho-p38MAPK is associated with senescent fibroblasts and epithelial cells (29, 30). Of note, the highly proliferative OSE tumor cells did not exhibit detectable levels of phospho-38MAPK. The mutant granulosa cells within the abnormal follicle-like structures also express markedly elevated levels of PTEN and negligible levels of phospho-AKT indicating that the PI3K pathway is severely inhibited. Although we hypothesized that disrupting Pten in the KrasG12D mutant strains might prevent cell cycle arrest and lead to granulosa cell tumor formation, the loss of Pten in the KrasG12D expressing cells did not prevent the formation of the abnormal follicle-like structures. However, the number of abnormal follicle-like structures was reduced and in some ovaries of the double Kras/Pten mutant mice regions of the ovary contained luteinized-like structures. Because this ovarian phenotype is more reminiscent of that observed in the Pten conditional knockout ovaries 18, it is possible that if the disruption of Pten occurs simultaneously with the onset of KrasG12D expression, the granulosa cells may luteinize. This is likely because KrasG12D expression did not impact ovarian cell function if expressed in luteinizing granulosa cells of the Pten fl/fl;KrasG12D;PGR-Cre mice. This agrees with previous reports indicating that KrasG12D can cause cell cycle arrest and senescence only in mitotic cells (44) and that the RAS-ERK1/2 pathway is critical for cell cycle arrest during luteinization (45). Remarkably, no GCTs formed in ovaries of the Ptenfl/fl,KrasG12D;Cyp19-Cre mice even at 10 months of age (data not shown) and were rare in the Pten fl/fl;Amhr2-Cre mice (19).

In marked contrast to the granulosa cells, the OSE cells present in the Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mouse ovaries transformed rapidly and developed into serous papillary cystadenocarcinomas between 1-3 months of age. That the tumors are derived from OSE cells was confirmed several criteria: LacZ staining of OSE cells only in Amhr2-Cre mice and the presence of the epithelial marker cytokeratin 8, an OSE cell marker that has been detected recently in the apical cell membrane of mouse serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary and human ovarian carcinoma, MUC16 (46, 47) and a specific marker of human ovarian serous papillary adenocarcinomas, WT-1. The Kras/Pten mutant OSE cells expressed elevated levels PI3K pathway components and phospho-ERK1/2, all of which were localized selectively to the invading OSE cells and were not present in the abnormal follicle-like structures. Conversely, the abnormal follicle-like structures contained high levels of phospho-p38MAPKwhereas the mutant OSE did not. Thus, these results combined with those of Connolly et al (33) and Szotek et al (48) clearly document that the Amhr2 gene is expressed in normal OSE cells. Although its role in normal, non-transformed cells remains to be clarified, AMH has been shown to block the proliferation of mouse and human ovarian cancer cell lines (48). Thus, the spontaneous and cell specific development of OSE cell tumors in the ovaries of the Ptenfl/fl,KrasG12D;Amhr2Cre mice described herein provides the first demonstration that Amhr2-Cre is expressed in murine OSE cells and can drive oncogenic transformation by generating cell specific mutants. Our results confirm and extend the studies of others who have generated OSE cell tumors by injecting adenoviral-Cre vectors into the ovarian bursa of Ptenfl/fl;KrasG12D mice (49) and Apcfl/fl;Ptenfl/fl mice (50). Furthermore, our results document that the OSE cells in the Ptenfl/fl,KrasG12D;Amhr2-Cre mice develop tumors whereas the granulosa cells do not.

In summary, these studies document that expression of KrasG12D and disruption of the Pten gene in granulosa cells results in a phenotype distinct from that occurring in OSE cells present in the same ovary (Fig. 6D). Whereas expression of KRASG12D leads to cell cycle arrest in granulosa cells where the Kras gene is silenced, it promotes proliferation in OSE cells where KRAS remains elevated. When Pten is disrupted in the KrasG12D strain, it enhances OSE cell proliferation and tumor formation, at least in part, by the sustained phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K pathway components and perhaps suppression of p38MAPK activation. Conversely, disrupting Pten in the Kras mutant granulosa cells does not reverse cell cycle arrest or induce tumorigenesis of these cells (Fig. 6D). By understanding how KRASG12D can exert completely opposite effects in these two cell populations within the same tissue may provide a key for controlling cancer development and progression. One key may be the total silencing of the Kras gene itself.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jan Gossen, Tyler Jacks, Richard Behringer and Hong Wu for providing the Cyp19-Cre mice, LSL-KrasG12D mice, Amhr2-Cre mice, and Ptenfl/fl mice, respectively. We also thank Dr. Richard Behringer and Dr. Robert Bast, Jr for the MUC16 antibody, Dr. Michael Mancini and members of the Microscopy Core (NIH-HD-07495) for their time and assistance and Yuet Lo for her many contributions. This work is supported by NIH grants NIH-HD16229, NIH-HD07495 (SCCPIR; Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research), Project II (JSR) and NIH Postdoctoral Training Grant NIH-HD07165 (HYF).

Supported in part by NIH-HD-16272 and a Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research (SCCPRIR), Project II (JSR), a Postdoctoral Fellowship HD-07165 (HYF), 1 U01 CA105352 (FD), NIH/NCI CA-077530 (JPL)

References

- 1.Kurman RJ, Shih Ie M. Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and molecular biology and their clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:151–60. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318161e4f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanderhyden BC, Shaw TJ, Ethier JF. Animal models of ovarian cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Donahoe PK, Szotek P, et al. Recombinant human Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits long-term growth of MIS type II receptor-directed transgenic mouse ovarian cancers in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1593–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards JS, Fitzpatrick SL, Clemens JW, Morris JK, Alliston T, Sirois J. Ovarian cell differentiation: a cascade of multiple hormones, cellular signals, and regulated genes. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1995;50:223–54. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matzuk MM. Revelations of ovarian follicle biology from gene knockout mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;163:61–6. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Robayna IJ, Falender AE, Ochsner S, Firestone GL, Richards JS. Follicle-Stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) and serum and glucocorticoid-lnduced kinase (Sgk): evidence for A kinase-independent signaling by FSH in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1283–300. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wayne CM, Fan HY, Cheng X, Richards JS. FSH-induces multiple signaling cascades: evidence that activation of SRC, RAS and the EGF receptor are critical for granulosa cell differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1940–57. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andric N, Ascoli M. A delayed gonadotropin-dependent and growth factor-mediated activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 cascade negatively regulates aromatase expression in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3308–20. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alam H, Maizels ET, Park Y, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is necessary for induction of select protein markers of follicular differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19431–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401235200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan HY, Shimada M, Liu Z, et al. Selective expression of KrasG12D in granulosa cells of the mouse ovary causes defects in follicle development and ovulation. Development. 2008;135:2127–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.020560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–6. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkisian CJ, Keister BA, Stairs DB, Boxer RB, Moody SE, Chodosh LA. Dose-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in vivo and its evasion during mammary tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:493–505. doi: 10.1038/ncb1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez F, Sellers WR. The PTEN tumor suppressor protein: an antagonist of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:M21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Ramjaun AR, Haiko P, et al. Binding of Ras to Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase p110alpha Is Required for Ras- Driven Tumorigenesis in Mice. Cell. 2007;129:957–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sansal I, Sellers WR. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2954–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulis ML, Parsons R. PTEN: from pathology to biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:478–83. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet. 1998;19:348–55. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan HY, Liu Z, Cahill N, Richards JS. Targeted disruption of Pten in ovarian granulosa cells enhances ovulation and extends the life span of luteal cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2128–40. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lague MN, Paquet M, Fan HY, et al. Synergistic effects of Pten loss and WNT/CTNNB1 signaling pathway activation in ovarian granulosa cell tumor development and progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:2062–72. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamin SP, Arango NA, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Behringer RR. Requirement of Bmpr1a for Mullerian duct regression during male sexual development. Nat Genet. 2002;32:408–10. doi: 10.1038/ng1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuveson DA, Shaw AT, Willis NA, et al. Endogenous oncogenic K-ras(G12D) stimulates proliferation and widespread neoplastic and developmental defects. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:375–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesche R, Groszer M, Gao J, et al. Cre/loxP-mediated inactivation of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene. Genesis. 2002;32:148–9. doi: 10.1002/gene.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, et al. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis. 2005;41:58–66. doi: 10.1002/gene.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fallest PC, Trader GL, Darrow JM, Shupnik MA. Regulation of rat luteinizing hormone beta gene expression in transgenic mice by steroids and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. Biol Reprod. 1995;53:103–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Shimada M, et al. Gene Expression Profiles of Cumulus Cell Oocyte Complexes during Ovulation Reveal Cumulus Cells Express Neuronal and Immune-Related Genes: Does this Expand Their Role in the Ovulation Process? Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1300–21. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Sato M, Li Q, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is a target of progesterone regulation in the preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1770–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01556-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyagi S, Chabes AL, Wysocka J, Herr W. E2F activation of S phase promoters via association with HCF-1 and the MLL family of histone H3K4 methyltransferases. Mol Cell. 2007;27:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buaas FW, Kirsh AL, Sharma M, et al. Plzf is required in adult male germ cells for stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2004;36:647–52. doi: 10.1038/ng1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwasa H, Han J, Ishikawa F. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 defines the common senescence-signaling pathway. Genes to Cells. 2003;8:131–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hui L, Bakiri L, Mairhorfer A, et al. p38a suppresses normal and cancer cell proliferation by antagonizing the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Nat Genet. 2007;39:741–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courtois-Cox S, Genther Williams SM, Reczek EE, et al. A negative feedback signaling network underlies oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:459–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and p53 tumor suppressor. PloS Biology. 2008;6:2853–68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connolly DC, Bao R, Nikitin AY, et al. Female mice chimeric for expression of the simian virus 40 TAg under control of the MISIIR promoter develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szotek PP, Chang HL, Brennand K, et al. Normal ovarian surface epithelial label-retaining cells exhibit stem/progenitor cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12469–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805012105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazin C, Wajapeyee N, Gobeil S, Virbasius CM, Green MR. An elaborate pathway required for Ras-mediated epigenetic silencing. Nature. 2007;449:1073–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson AC. Setting the stage for S phase. Mol Cell. 2007;27:176–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodruff TK. Role of inhibins and activins in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2002;107:293–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3587-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pangas SA, Woodruff TK. Activin signal transduction pathways. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:309–14. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A. Alpha-inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature. 1992;360:313–9. doi: 10.1038/360313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serrano M, Blasco MA. Putting the stress on senescence. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:748–53. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, et al. Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:653–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McConnell MJ, Chevallier N, Berkofsky-Fessler W, et al. Growth suppression by acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated protein PLZF is mediated by repression of c-myc expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9375–88. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9375-9388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campisi J. Suppressing cancer: the importance of being senescent. Science. 2005;309:886–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1116801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan HY, Liu Z, Shimada M, et al. ERK1/2 in ovarian granulosa cells are essential for female fertility. Science. 2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1171396. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xing D, Orsulic S. A mouse model for the molecular characterization of brca1-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8949–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Cheon DJ, Lu Z, et al. MUC16 expression during embryogenesis, in adult tissues, and ovarian cancer in the mouse. Differentiation. 2008;76:1081–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, et al. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11154–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinulescu DM, Ince TA, Quade BJ, Shafer SA, Crowley D, Jacks T. Role of K-ras and Pten in the development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Nat Med. 2005;11:63–70. doi: 10.1038/nm1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu R, Hendrix-Lucas N, Kuick R, et al. Mouse model of human ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma based on somatic defects in the Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Pten signaling pathways. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:321–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.