Abstract

To identify cytoskeletal proteins that change conformation or assembly within stressed cells, in situ labeling of sterically shielded cysteines with fluorophores was analyzed by fluorescence imaging, quantitative mass spectrometry, and sequential two-dye labeling. Within red blood cells, shotgun labeling showed that shielded cysteines in the two isoforms of the cytoskeletal protein spectrin were increasingly labeled as a function of shear stress and time, indicative of forced unfolding of specific domains. Within mesenchymal stem cells—as a prototypical adherent cell—nonmuscle myosin IIA and vimentin are just two of the cytoskeletal proteins identified that show differential labeling in tensed versus drug-relaxed cells. Cysteine labeling of proteins within live cells can thus be used to fluorescently map out sites of molecular-scale deformation, and the results also suggest means to colocalize signaling events such as phosphorylation with forced unfolding.

Force-induced changes in protein conformation have long been postulated to contribute to the deformability of cells (1, 2). Likewise, in cell adhesion, forces of pico-Newton magnitude that result from cells pulling on matrix (3) are believed to induce conformational changes that initiate essential anchorage signals (4-8). Single-molecule measurements indeed show that domain unfolding occurs in reversible extension of purified cytoskeletal, motor, and matrix adhesion proteins (9-12), and simulations of the molecular dynamics of protein extension have helped to clarify mechanisms (13-15). Direct cell-level evidence is lacking or even contrary to forced unfolding (16), although cytoskeletal association of a large and rare conformation-sensitive antibody has suggested extension of a proline-rich region in one protein within spread, fixed cells (17). The more broadly directed “shotgun” approach here is applied to live cells under physiological stresses and exploits small thiol-reactive probes that permanently label force-sensitive domains.

Cysteine (Cys) is a moderately hydrophobic amino acid that is frequently shielded by tertiary or quaternary protein structure. Labeling of cysteine's SH moiety has been exploited in solution denaturation studies on a few small purified proteins (18, 19), as well as in an anemia-causing proline mutation in the red blood cell (RBC) protein spectrin (20). In addition, forced unfolding of single proteins with core-sequestered disulfides demonstrates reduction of the S-S within seconds by reactive thiols in the medium (21, 22). We show here, in intact cells, that force-induced changes in protein structure can also expose—for relatively rapid reaction—specific buried Cys (Fig. 1) in a number of key cytoskeletal proteins. Sequential n-dye-labeling with different color fluorophores (n = 2 here) proves to be a facile approach to amplifying signals from shielded sites relative to prelabeled surface sites (23). We illustrate the range of this in situ “Cys shotgun” approach, first, with the relatively simple human RBC, which allows for the most direct demonstration of forced unfolding in fluid-stressed cells, then, with human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) under cell-generated tension.

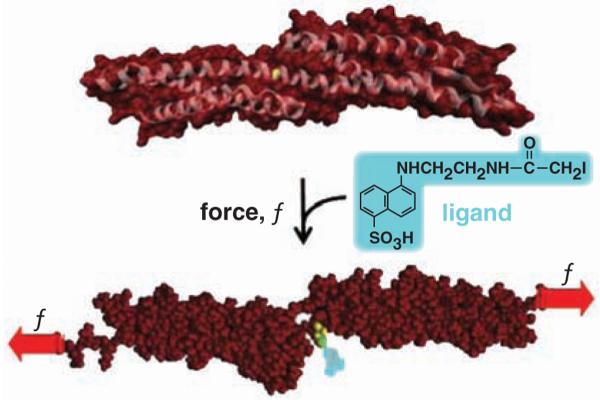

Fig. 1.

Force-induced changes in protein structure within cells are hypothesized to expose novel binding sites for ligands. This example of a molecular dynamics simulation shows that Cys1167 in β-spectrin exposes 0 Å2 surface area (of 224 Å2) until forced extension [e.g., (15)] exposes the -SH for reaction with a thiol-reactive fluorescent dye.

Red blood cells deform under the incessant stresses of blood flow, and the spectrin membrane cytoskeleton has proven central to cell deformability (24). Spectrin's α and β chains interact to cross-link F-actin in this cell, and in single-molecule studies, spectrin's tandem array of helical bundle domains (Fig. 1) are found to unfold at low forces [~picoNewton (25-27)] that could be generated by just a few myosin motor molecules. There are 20 Cys in α-spectrin and 15 Cys in β-spectrin, and some of these appear buried in crystal structures (Fig. 1) and homology models. To assess exposure of Cys in unfolding of spectrin and all of the other RBC membrane proteins, cells were reversibly lysed to make hemoglobin-depleted pink “ghosts” that were resealed with entrapment of the Cys-reactive fluorophore IAEDANS. Dye-loaded cells were then either held static in suspension at various temperatures or else sheared over a physiological range of stresses with a standard fluid shearing device. After 5 min or more, cells were relysed, excess dye was quenched, and cells were imaged to assess membrane labeling (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

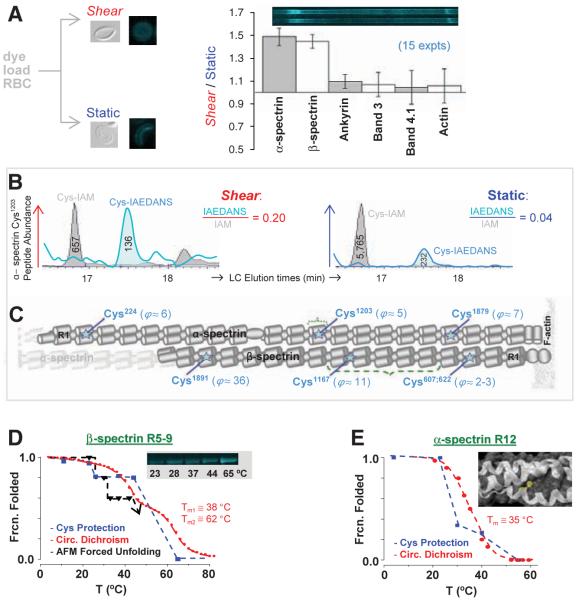

In-cell labeling of RBCs under stressed versus static conditions demonstrates force-enhanced labeling of spectrin sites with Cys identification by quantitative MS. (A) Inset images show shear-distorted or round RBC ghosts fixed by glutaraldehyde, as well as fluorescence microscopy of membranes after IAEDANS reaction under either shear (stress σ = 0.93 Pa) or static conditions (60 min, 37°C). SDS 1D-PAGE separations of ghost lysates demonstrate shear-enhanced labeling of α-and β-spectrin, but no significant differences for other membrane proteins (±SD). (B) Extracted ion chromatograms for α12's Cys1203-containing peptide from shear and static samples. Ratios of peak areas for IAEDANS- and IAM-labeled peptides provide measures of relative dye labeling. (C) Positions along α- and β-spectrin with shear/static-labeling differentials, ϕ ≥ 2 (seetable S1). (D) Recombinant β-R5-9 construct labeled in solution by IAEDANS with increasing temperature reveals a step-wise increase in labeling extent; this is inverted and normalized to report fraction folded. The increase at T > 23°C coincides with unfolding of repeat β9, as determined by both circular dichroism (CD) and forced unfolding with an AFM. The numbered Tm are the two melting temperatures from CD. (E) Homology model of α-R12 with Cys1203 highlighted in yellow. Fraction of α12 folded versus temperature based on cysteine labeling results (blue) and CD measurements (red) (28).

Solubilized cells were denatured, and all Cys that were not dye-labeled were alkylated with iodoacetamide (IAM). Separation of membrane proteins by one-dimensional (1D) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by densitometry, showed 50% more IAEDANS fluorescence in the bands of α- and β-spectrin from the shear samples (Fig. 2A: 15 runs at 37°C); sequential two-dye labeling magnifies this difference to >500%, as described below. Labeling under shear is only enhanced for spectrin: Labeling of the other major membrane proteins (ankyrin, protein 4.1, actin, etc.) was not affected by fluid shear, which suggests, together with additional results below, that mixing is not limiting.

Liquid chromatography-coupled tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) was used to identify and quantify IAEDANS-modified Cys sites in spectrin bands after excision and trypsinization. Within α- and β-spectrin, respectively, 13 and 14 IAEDANS-Cys were detected (table S1). Because surface-exposed Cys are predominantly IAEDANS labeled and buried Cys are largely inaccessible until subsequent denaturation and IAM labeling, site-specific ratios of (IAEDANS/IAM) in ion chromatogram elution profiles (e.g., Fig. 2B) quantify Cys exposure. A majority of ratios are the same for shear and static samples, but at least six Cys sites are distinct with results for the ratio of dye-labeling rates over time ϕ(t) = [(IAEDANS/IAM)shear/(IAEDANS/IAM)static] that are typically in the range of ϕ ≈ 5 to 10 at 60 min, but as high as 36 (Fig. 2C). Cleavage patterns of β-spectrin treated with NTCB (2-nitro-5-thiocyanobenzoic acid), which cleaves peptide bonds at unlabeled Cys (fig. S1A), are distinct for shear and static samples, consistent with qualitative differences in Cys exposure.

The structure of shear-sensitive β-R8-9 (28) shows the shear-labeled Cysβ1167 is 100% buried or shielded within a tertiary fold—at least until force induces localized unfolding (Fig. 1). A recombinant multidomain construct β-R5-9 was, therefore, Cys-labeled at different temperatures for a fixed time and then analyzed by both fluorescence imaging and MS. Construct labeling is significant only at temperature T ≥ 25°C (Fig. 2D), with evidence from MS of Cysβ1167 labeling at 25°C. This apparent transition corresponds to the transition midpoint temperature (Tm) of β-R9 (29) and correlates with both the thermally induced loss of helicity and the loss of mechanical stability of R9 as determined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) forced extension. At higher temperatures, additional repeats are labeled as helicity is lost.

The shear-sensitive Cysα1203 was also studied in solution with a recombinant α-R12 domain for which modeling predicts partial shielding (Fig. 2E). At a given temperature, the ratio of dye-labeling rates Φ(T) for urea-denaturing conditions versus native conditions relates to the steric protection of a partially exposed cysteine (19) (fig. S2). The recombinant's Φ(37°C) ≈ 4 approximates the LC-MS/MS result for shear versus static cells' Φ(37°C) = 5 (Fig. 2C). Normalization and rescaling to the folded state maximum Φmax = Φ(4°C) gives the fraction folded, and this decreases with T in parallel again with the helicity loss upon heating (Fig. 2E and fig. S2).

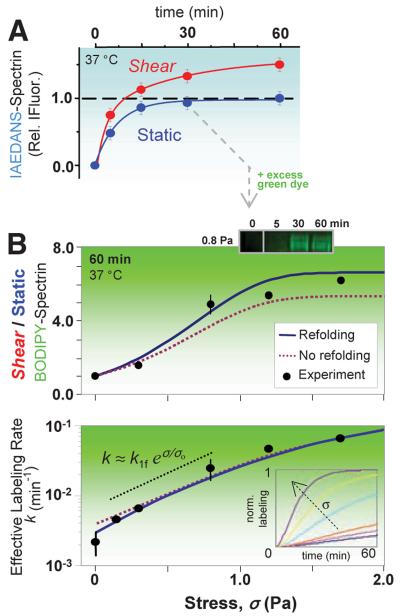

Within RBCs, the labeling kinetics for IAEDANS provides a basis for dramatically increasing the shear/static-labeling ratio. Surface-exposed Cys in spectrin label to saturation within 30 to 60 min with a first-order rate constant (0.13 min-1) (Fig. 3A), whereas in the shear sample, the ~50% enhanced labeling is slower (0.04 min-1), consistent with a second population of shear-exposed Cys sites. In sequential two-dye labeling, static-accessible sites are labeled to near saturation with IAEDANS (blue), and then shear is applied with labeling by a second (green) Cys-reactive fluorophore (Fig. 3B). N-(4,4-Difluoro-1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-2-yl) iodoacetamide (BODIPY-IA) labeling of spectrin within RBCs increases with both time and stress, yielding results for the shear/static ratio of ~5 to 6.5 after 60 min at the highest shears of σ = 0.8 to 1.7 Pa. Site-specific MS gave <ϕ> ≈ 10 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

Stress-dependent kinetics and sequential two-dye labeling for amplification. (A) Sheared (σ = 0.93 Pa) versus static RBCs show distinct labeling kinetics for spectrin. IAEDANS labeling (at 2.5 mM) of the static-labeled, surface-exposed spectrin sites fit a first-order rate of 0.13 min-1; the shear-exposed sites (66% more from fit) label more slowly at 0.04 min-1. (B) Sequential labeling entails labeling of the surface Cys (blue) for 30 min, after which BODIPY-IA (green) is added at >10-fold excess (6 mM). Half of the cells are then exposed to shear with timed aliquots again quenched by IAM and analyzed by densitometry of the green fluorescent spectrin. BODIPY-spectrin at 60 min increases with σ (top) as does the effective rate of labeling (bottom). Error bars (±SD) indicate three or more measurements (six for σ = 0). The data are fit by the exact solution of the fLL reaction for P(t), either with or without refolding (SOM text). The intermediate regime of stress (dotted black line) is dominated by unfolding and increases exponentially with stress, exhibiting a characteristic stress of σo ≈ 0.5 Pa and giving k1f ≈ 0.004 min-1. (Inset) The effect of force on computed kinetics using the fit parameters.

The effective labeling rate k for the secondary BODIPY-IA-labeling reaction is 30 times as fast in maximally sheared cells as in static cells (Fig. 3B) and fits to a force (f)-dependent Linderstrom-Lang (fLL) scheme in which shear stress, proportional to f, shifts the conformational equilibrium.

Similar to forced unfolding in the cited single-molecule studies, the folded state N shifts toward unfolded state U with a force bias on the forward and reverse reactions, and the activated transition state I* along the reaction coordinate x is at the respective distances Δx (>0, N→ I*) and Δx′ (<0, U→ I*). Here, the U state's exposed Cys can be labeled by dye at concentration c and rate k2 to yield measured product P (table S1 and fig. S1B). The analytical solution to the fLL scheme (SOM text) fits well to the spectrin in-cell experiments here when we use parameter values similar to those obtained from single-molecule studies on spectrin, such as k1f ≈ 0.002 min-1 (25). The fits are also consistent with expectations that (i) the refolding rate is only important in the static sample and at low stress, (ii) labeling is limiting at very high stress, and (iii) labeling in the intermediate stress regime is sufficiently rapid that the rate of exposure of sequestered Cys is exponential with respect to stress.

Consistent with past speculations that spectrin unfolding occurs to some extent within RBCs (1, 30), about 40% of spectrin's domains studied as isolated domains unfold with Tm ≤ 37°C (29). Within static cells, IAEDANS labeling of spectrin Cys occurs slowly at low temperature as expected (fig. S3A), and, although site-selective labeling rates will be needed for an accurate assessment of in-cell melting of spectrin, 60 min of labeling yields an apparent melting curve (fig. S3B) in close agreement with the summed melting profile calculated from individual recombinant spectrin domains (29). Moreover, at all temperatures up to thermal disruption of cells (~45°C), shear enhances labeling of spectrin but not actin (fig. S3).

Mechanically induced changes in protein structure within other cells are likely to be of importance not only to cell deformability but also to various mechano-signaling processes. MSCs, for example, are contractile (31) and strain the underlying matrix in differentiation (32). Traction force measurements on soft matrices show that MSCs, like many tissue cells (4), generate stresses (~kPa) that are ~1000 times fluid shear stresses imposed on RBCs. Inhibition of nonmuscle myosin II (NMM II) with the drug blebbistatin (33) relaxes and softens MSCs (31) and also blocks differentiation. For molecular insight into structural changes, as well as a proteomic characterization of MSCs, the Cys shotgun method was applied to these adherent stem cells with and without blebbistatin (Fig. 4A).

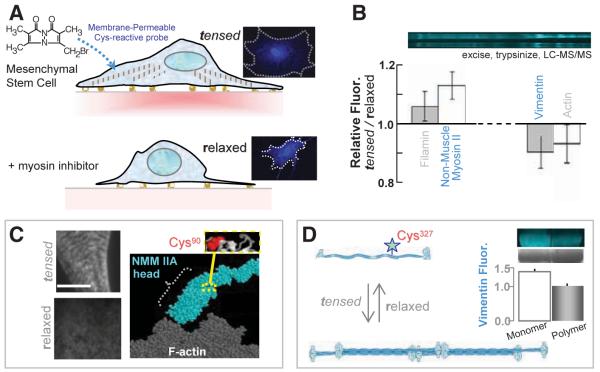

Fig. 4.

In-cell labeling of human stem cells either tensed or relaxed. (A) The membrane-permeable Cys-reactive fluorophore, mBBr, was added to 1-week cultures of MSCs with active myosins and tensed cytoskeletons and also to MSCs treated with myosin-inhibiting blebbistatin for 1 day to relax the cells. Imaging shows homogeneous labeling with 0.5 mM mBBr for 40 min. (B) SDS-PAGE and densitometry of samples (±SD, three experiments) that were either blebbistatin treated (relaxed) or untreated (tensed) show several protein bands in which the fluorescence intensities are different (normalized to protein load). Lysates were quenched with β-mercaptoethanol (50 mM) before analysis. (C) Immunofluorescence imaging of NMM IIA in tensed cells (top) and relaxed cells (bottom) indicates a spatial redistribution of myosin with drug. Scale, 5 μm. MS analyses of excised myosin bands detected labeling of Cys90, which appears buried within the fold of NMM IIA homology models. (D) Vimentin labeling in monomeric, and polymeric forms display different degrees of fluorescence (error bar from two experiments), which indicates that polymerization sterically blocks Cys327 for labeling.

The membrane-permeable, Cys-reactive fluorophore monobromobimane (mBBr) shows labeling of the cytoskeleton, nucleus, and other structures after fixation and washing—without perturbing cell area (fig. S4A). This suggests that labeling does not greatly disturb MSCs (23). Cell lysates for the tensed cells and blebbistatin-relaxed cells were Cys-quenched, and, once again, 1D SDS-PAGE was followed by densitometry and then LC-MS/MS analyses of all prominently labeled bands (>40 kD) (Fig. 4B). The cytoskeletal proteome of MSCs (table S2) appears typical of nucleated cells in consisting of actin, myosin, the actin-binding proteins filamin and nonerythroid spectrin, as well as tubulin and the mesenchymal intermediate filament protein vimentin. Site-specific differences in Cys labeling with blebbistatin are seen in several proteins, and two prove illustrative.

Nonmuscle myosin IIA shows greater mBBr-labeling in the tensed state of MSCs for which immunofluorescence imaging shows cytoskeletal striation (Fig. 4C); in contrast, blebbistatin disorganizes NMM II, consistent with blocking it in a low-affinity state for actin (34). MS analysis identifies Cys90 as a differentially labeled site, and homology models of NMM II show this site is buried between the head and rod domains. Transient allosteric changes that occur in stress generation during NMMII's normal ATP hydrolysis likely expose Cys90, whereas blebbistatin eliminates force-generation and keeps this site buried.

Differential labeling in MSCs is also found at the single Cys site of vimentin (Fig. 4D): Cys327 is in the central coil that mediates coiled-coil polymerization (35). Quaternary structure changes in solution have been exploited previously to understand hemoglobin tetramerization [e.g., (36)], as well as actin-binding interfaces [e.g., (37)], and here blebbistatin-induced depolymerization of vimentin with Cys exposure in the MSCs appears consistent with blebbistatin-induced softening of the cells (32). Purified vimentin confirms enhanced labeling as monomer (~50% more) versus polymer (Fig. 4D), and Western blot analysis plus immunofluorescence imaging of MSCs grown on various matrices show that chronic blebbistatin treatment consistently down-regulates vimentin (fig. S4, B and C). Short treatments with blebbistatin (~1 hour instead of 1 day) also show that mBBr-vimentin measured in cell lysates increases significantly even though Western blots and immunofluorescence indicate no differences in overall expression. In-cell labeling thus identifies structural changes within tensed cell but not relaxing cells.

Nucleated cells typified by MSCs have a complex intracellular force map when inferred from cell tractions in the surrounding matrix (4, 32, 38), and even simple cells such as RBCs sustain stresses at the molecular level in unknown ways (1, 29). The overall Cys-shotgun methodology here not only provides evidence of force-induced changes that propagate in both tertiary and quaternary structures within cells but also, through LC-MS/MS, provides useful proteomic information, as well as new opportunities for fluorescence imaging. In addition, whereas fluorescence resonance energy-transfer imaging of labeled proteins within cells [e.g., (39)] might allow imaging of force-induced conformational changes in real time, the time-integrated analyses here are complementary and also readily extended to engineered sites in wild-type and mutant proteins for in-cell assessments of perturbations. This idea seems very likely to extend to coincidence detection of Cys labeling with posttranslational events such as phosphorylation so as to precisely colocalize conformational changes with signaling events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Ortiz for the Molecular Dynamics image, X. An for purified protein, A. Engler for culture and help with MSCs, and A. Kashina for helpful comments on the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge support from NIH grants (D.E.D., D.W.S.), NIH Training Grants (C.P.J., C.C.), as well as NSF and Muscular Dystrophy Association grants (D.E.D.).

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/317/5838/663/DC1

References and Notes

- 1.Evans EA, Skalak R. Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Biomembranes. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1980. p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson HP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:10114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balaban NQ, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:466. doi: 10.1038/35074532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Kaverina I, Small JV, Wang YL. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:881. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alenghat FJ, Ingber DE. Sci. STKE. 2002;2002(119):PE6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans EA, Calderwood DA. Science. 2007;316:1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1137592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:265. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bershadsky A, Kozlov M, Geiger B. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:472. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. Science. 1997;276:1109. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberhauser AF, Marszalek PE, Erickson HP, Fernandez JM. Nature. 1998;393:181. doi: 10.1038/30270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwaiger I, Sattler C, Hostetter DR, Rief M. Nat. Mater. 2002;1:232. doi: 10.1038/nmat776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee G, et al. Nature. 2006;440:246. doi: 10.1038/nature04437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotomayor M, Schulten K. Science. 2007;316:1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1137591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams PM, et al. Nature. 2003;422:446. doi: 10.1038/nature01517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz V, Nielsen SO, Klein ML, Discher DE. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;349:638. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu-Lail NI, Ohashi T, Clark RL, Erickson HP, Zauscher S. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:175. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawada Y, et al. Cell. 2006;127:1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha JH, Loh SN. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:730. doi: 10.1038/1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverman JA, Harbury PB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson CP, et al. Blood. 2007;109:3538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carl P, Kwok CH, Manderson G, Speicher DW, Discher DE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031409698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiita AP, Ainavarapu SR, Huang HH, Fernandez JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:7222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 24.Mohandas N, Evans EA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1994;23:787. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.004035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rief M, Pascual J, Saraste M, Gaub HE. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;286:553. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law R, et al. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3286. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74747-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randles LG, Rounsevell RW, Clarke J. Biophys. J. 2007;92:571. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusunoki H, MacDonald RI, Mondragon A. Structure. 2004;12:645. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An X, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JC, Discher DE. Biophys. J. 2001;81:3178. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75954-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:483. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Cell. 2006;126:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straight AF, et al. Science. 2003;299:1743. doi: 10.1126/science.1081412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramamurthy B, Yengo CM, Straight AF, Mitchison TJ, Sweeney HL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14832. doi: 10.1021/bi0490284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrmann H, Aebi U. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiancone E, Currell DL, Vecchini P, Antonini E, Wyman J. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:4105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun S, Footer M, Matsudaira P. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:421. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang N, et al. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C606. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00269.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraynov VS, et al. Science. 2000;290:333. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.