Abstract

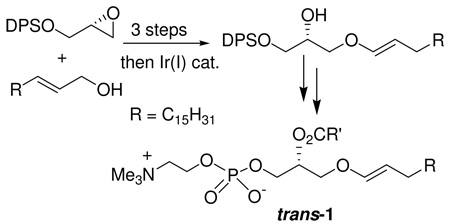

To assess the antioxidant behavior of trans-1, we first synthesized trans-allyl ether 4 by opening an (S)-glycidol derivative with an (E)-alk-2-en-ol, and then produced the unnatural E-enol ether 1 by a stereoselective iridium(I)-catalyzed olefin isomerization. Natural cis-1 was preferentially degraded by HOCl and was more protective than trans-1 against lipid peroxidation induced by a free-radical initiator, demonstrating that the geometry of the 1’-alkenyloxy bond participates in the antioxidant defensive role of 1.

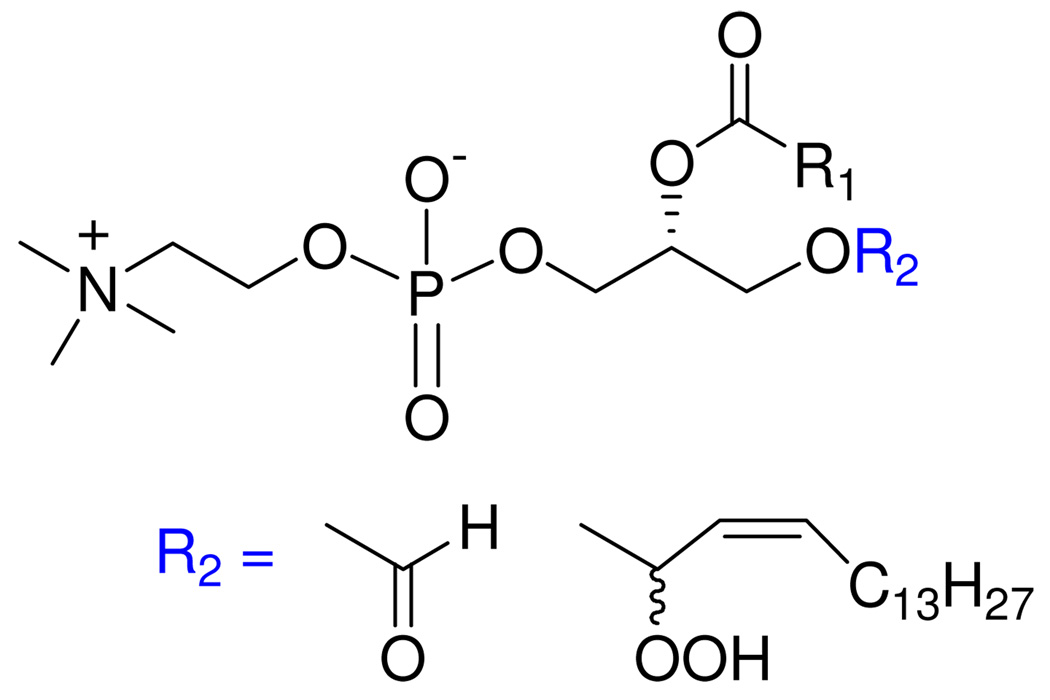

Plasmalogens are a subclass of glycerophospholipids that bear an 1-O-alk-1’-(Z)-enyl chain at the sn-1 position of glycerol (typically a 16-carbon chain), an sn-2 fatty acyl chain (typically unsaturated or polyunsaturated), and a polar head group at the sn-3 position (predominantly a mixture of phosphoethanolamine and phosphocholine).1 Plasmalogens comprise about 20% of the total phospholipids in humans; they are especially abundant in human cardiac, skeletal muscle, and nervous tissues, which contain high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids.2 Since plasmalogen-deficient cells were more susceptible to free radical mediated oxidative damage than cells with normal plasmalogen levels,3 and because enol ethers are known to be susceptible to oxidation,4 it has been proposed that the Z-enol ether functionality, which is unique to plasmalogens, may serve as a trap for reactive oxygen species. The vinyl ether linkage is located in close proximity to the lipid-water interface, and may thus protect the polyunsaturated chains of phospholipids in membranes and lipoproteins from oxidation.5 The putative intermediates formed by [2+2] and [2+4] cycloaddition of singlet oxygen to this linkage are dioxetane and ene intermediates, respectively, which subsequently undergo degradation to generate a complex mixture of fatty aldehydes (such as pentadecanal), 1-formyl-2-acyl-sn-glycerophospholipids, and 1-(O-1’-hydroperoxy)-2-acyl-sn-glycero-3-phospholipids (Fig. 2).6 Decomposition of the allylic hydroperoxides produces plasmalogen epoxides via a radical process, and 1-formyl- and 1-lyso-phospholipids by hydrolytic processes.6d,7

Figure 2.

Structures of 1-formyl- and 1-(O-1’-hydroperoxy)plasmalogen derivatives formed on reaction of cis-1 with reactive oxygen species.

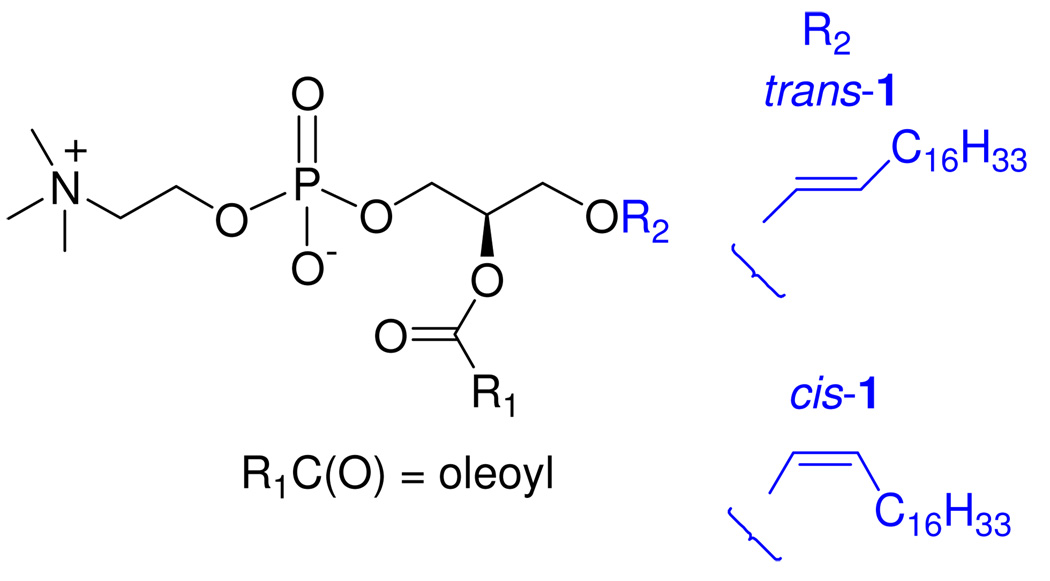

Plasmalogens are more susceptible to oxidation than phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin, the other major membrane phospholipids;8 however, sphingomyelin has also been found to inhibit PC peroxidation, albeit less efficiently than plasmalogen, but its long-chain base contains a trans double bond near the membrane-water interface.9a To elucidate the role of the naturally occurring (Z)-O-vinyl linkage of plasmalogen in protecting polyunsaturated lipids from oxidative degradation, we describe herein the first chemical synthesis of an unnatural analogue of plasmalogen with an (E)-O-vinyl linkage at the sn-1 position (trans-1, Figure 1)10 and a comparison of the antioxidant effects of cis- and trans-1 in two model systems.

Figure 1.

Structures of naturally occurring cis-1 and the unnatural trans-1 analogue.

The first model system we investigated was the reaction of cis- and trans-1 with hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a highly reactive oxidant and chlorinating agent that is produced endogenously when physiological concentrations of chloride ion are oxidized by the myeloperoxidase-catalyzed decomposition of hydrogen peroxide.11 HOCl reacts with many biological molecules,12 including the double bonds of lipids, to generate chlorinated products.13 Recently, Davies and co-workers showed that the kinetics of vinyl ether oxidation is several orders of magnitude greater than that of aliphatic alkenes.14 The products of plasmalogen oxidation by HOCl are 2-chloro fatty aldehydes and 1-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC).15 Phospholipid chlorohydrins in the sn-2 chain of unsaturated LPC molecular species are also formed as secondary reaction products by electrophilic attack of HOCl on alkenyl double bonds.16 These chlorinated lipid species accumulate in activated neutrophils, monocytes, ischemic myocardium, and human atherosclerotic lesions, and have potential roles in many inflammatory disorders.17

Peroxidation of phospholipids containing a polyunsaturated fatty acyl chain such as linolenic acid has been studied frequently by using free-radical initiators, such as the water-soluble thermolabile free-radical generator 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH).18 As a model system to compare the antioxidant capability of cis- and trans-1, we studied the influence of 1 on the rate and extent of peroxidation of 1-palmitoyl-2-linolenoyl-phosphatidylcholine (16:0-18:2-PC) in liposomes exposed to AAPH. The reaction kinetics were monitored by measuring the formation of conjugated diene lipid hydroperoxides, as monitored spectrophotometrically by the absorbance at 234 nm.9 A234 is diminished when AAPH-induced free-radical chain initiation in a polyunsaturated acyl chain is suppressed.

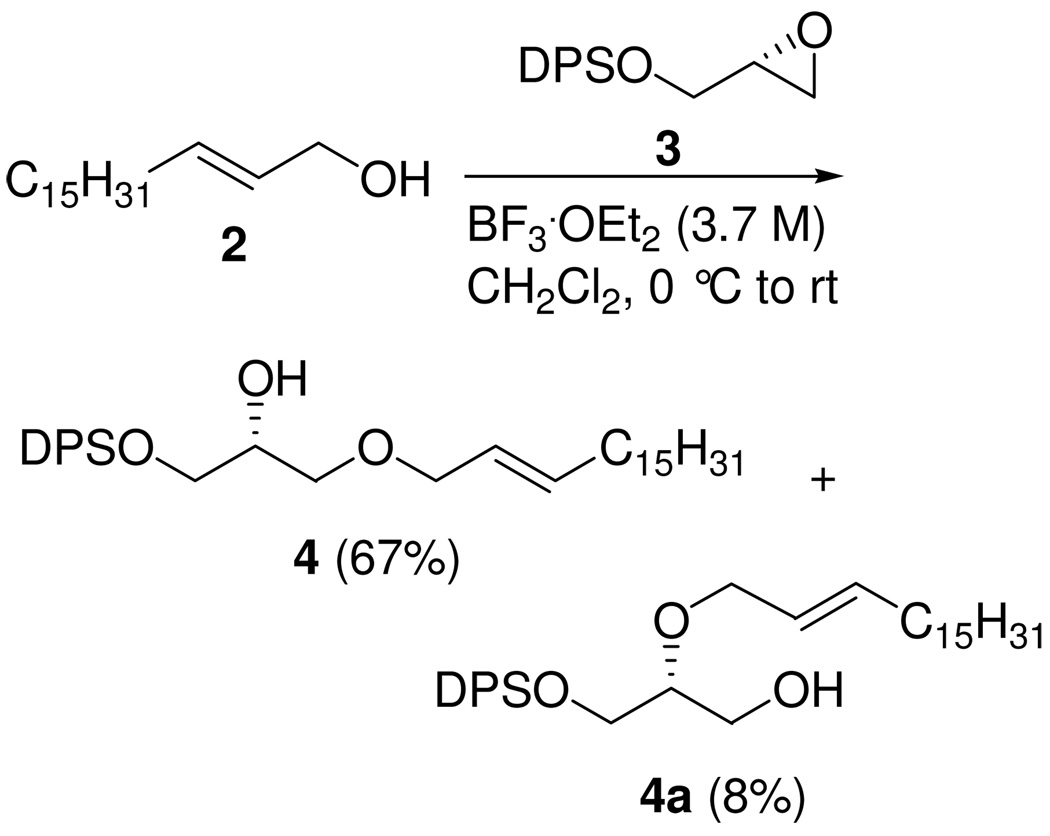

Previous reports of the preparation of 1-O-alkenyl ether derivatives of glycerol were based on elimination reactions of α-halo cyclic glycerol acetals, which gave low yields and poor stereoselectivity.19 To construct the glycerol backbone with an O-1’-alkenyl chain at the sn-1 position, we used (S)-glycidol and 1-hexadecanol as the starting materials for the synthesis of trans-1 (see Supporting Information). As shown in Scheme 1, the DPS ether of (S)-glycidol (3) was employed in a regioselective BF3•OEt2-mediated ring-opening reaction20 of (E)-octadec-2-en-1-ol (2), prepared by DIBALH reduction of ethyl (E)-octadecanoate. The expected attack at C-3 provided an 8:1 (separable) mixture of allyl ether 4 and the undesired regioisomer 4a.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of Allyl Ether 4

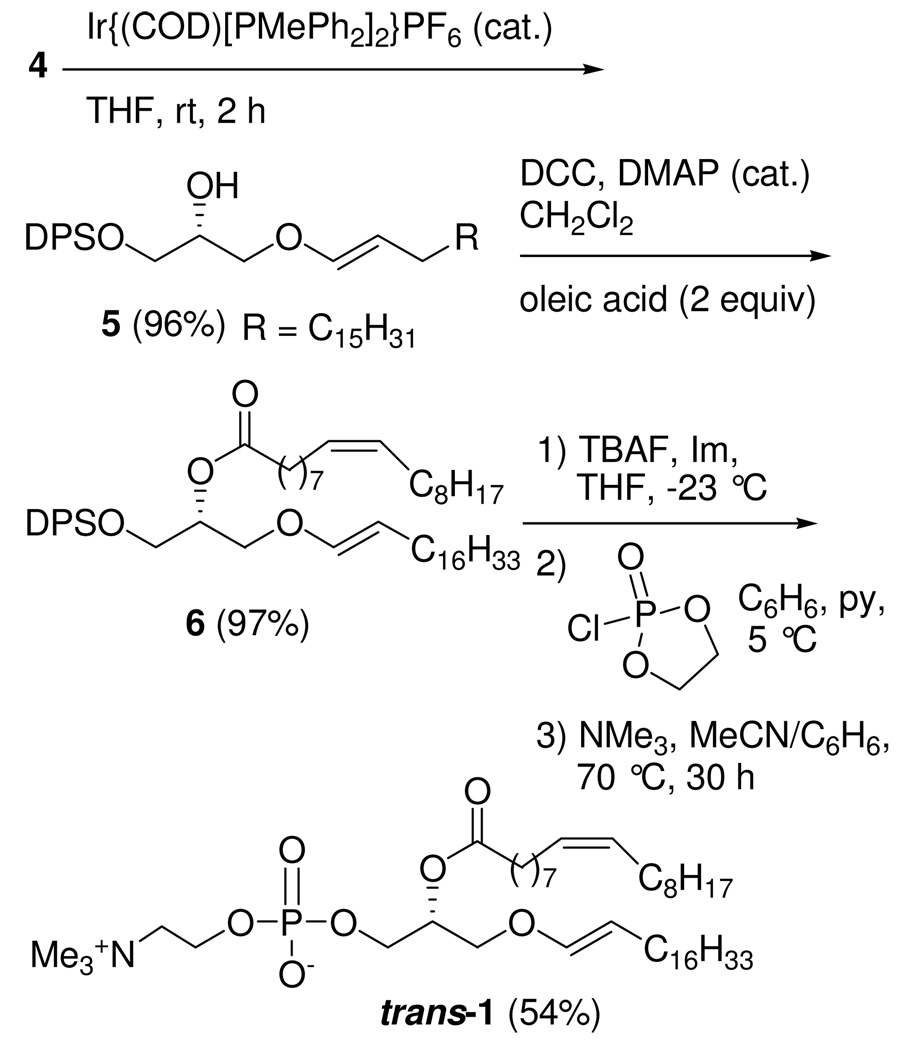

Next, isomerization of the double bond was investigated using transition metal complexes as catalysts.21 An initial attempt using RhCl3•3H2O22 as a catalyst resulted in no reaction. Fortunately, we found that use of (1,5-cyclooctadiene)bis(methyldiphenylphosphine)iridium(I) hexafluorophosphate (Ir(COD)[PMePh2]2PF6),23 after activation with hydrogen for 5 min, resulted in the stereoselective isomerization of allylic ether 4 to enol ether 5 in 2 h at rt, and with the desired E double bond as the only product (Scheme 2). The coupling constant (JH1’–H2’ = 12.6 Hz at δ 6.24 ppm) in the 1H-NMR spectrum of 5 is indicative of the desired E isomer, which was obtained in 96% yield.24 sec-Alcohol 5 was then esterified with oleic acid, using DCC in the presence of DMAP, affording ester 6. The final steps in the synthesis of trans-1 require conditions that do not cleave the acid-labile and oxidizable vinyl ether moiety or the alkaline-labile acyl ester bond. After the silyl ether in 6 was removed using TBAF (6 equiv) and imidazole (2.5 equiv) in THF at −23 °C, the phosphocholine head group was installed at the sn-3 position in 54% overall yield without accompanying acyl migration by opening of a cyclic phospholane intermediate in a pressure tube with anhydrous trimethylamine (200 equiv, condensed at −10 °C) in MeCN/C6H6 (3:1) in the presence of pyridine.25

Scheme 2.

Ir(I)-mediated Olefin Isomerization and Final Conversion to trans-1

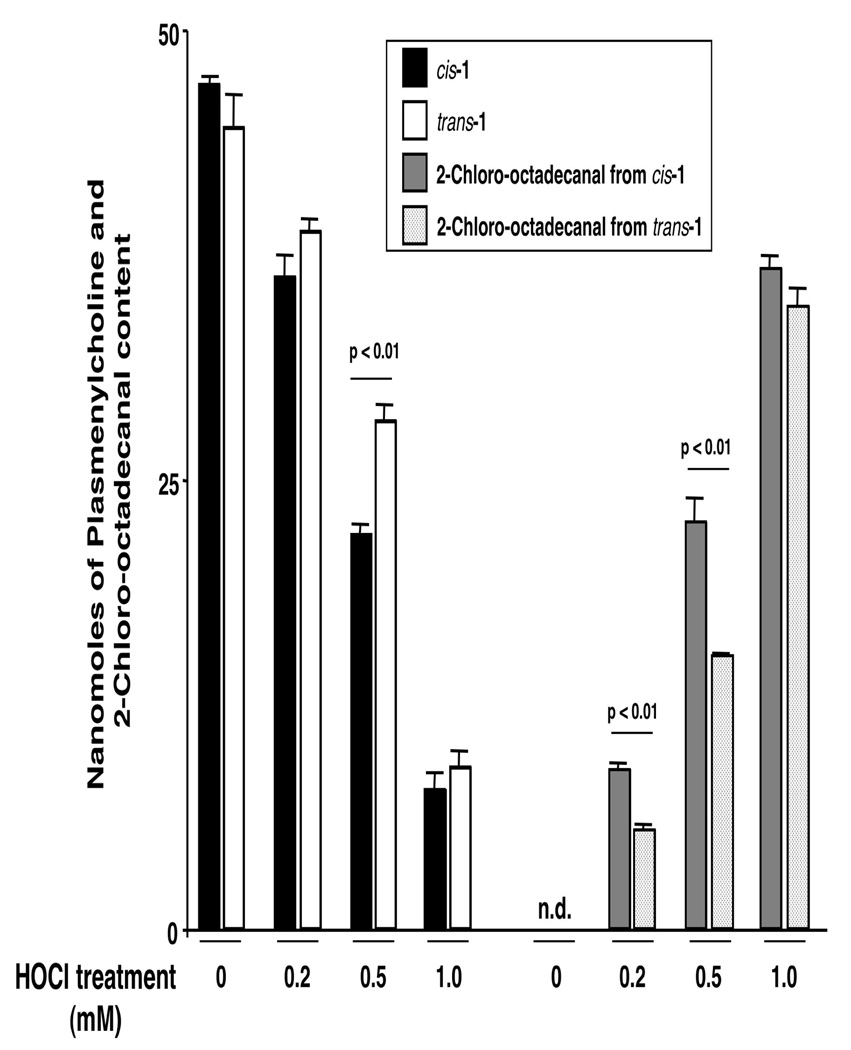

We analyzed the HOCl oxidation reaction of cis-and trans-1 using increasing concentrations of HOCl. At equimolar concentrations of HOCl and 1, the extent of plasmalogen oxidation was minimal with both species (data not shown). Figure 3 shows the loss of both cis- and trans-1 as the HOCl concentration was increased. At both a 2- and 5-fold molar ratio of [HOCl]/[1], the cis-vinyl ether linkage was oxidized faster than the trans linkage. This selectivity was not observed at a higher HOCl concentration (1.0 mM).

Figure 3.

Disparate cis- and trans-1 oxidation by HOCl.

The bars show the amounts of enol ether remaining (left panel) and the amount of 2-chloro-aldehyde produced (right panel) (both in nmoles) after treatment with various HOCl concentrations (in mM) for 5 min at 37 °C. Data are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. See S.I. for experimental details.

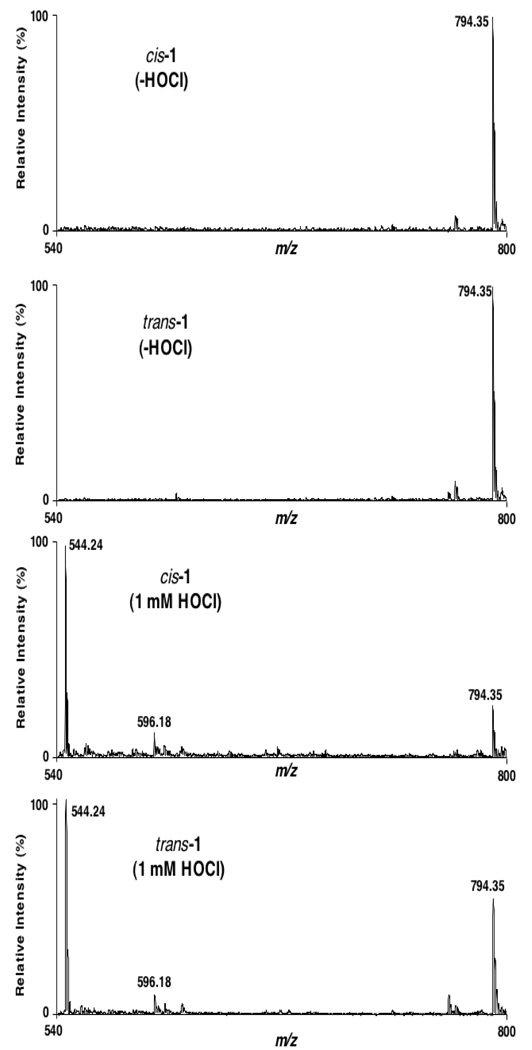

ESI-MS analyses of the reaction mixture with 1 mM HOCl demonstrated that the other product of HOCl oxidation is LPC containing an oleic acid moiety (m/z 544.24) (Figure 4). The chlorohydrin of this material, formed by reaction with HOCl,15 is a by-product with m/z 596.18. In these spectra, m/z 794.35 is the unreacted cis- or trans-1. These spectra were acquired in the presence of dilute NaOH, which facilitates the production of the observed sodiated adduct ions.

Figure 4.

ESI-MS of the HOCl oxidation products.

cis- or trans-1 (50 nmol) was incubated in 500 µL of 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (pH 7.0) in the presence or absence of 1 mM chloride-free NaOCl for 5 min at 37 °C. After the reactions were terminated by addition of MeOH, products were extracted into CHCl3. Reaction products and precursor cis-or trans-1 were resuspended in 500 µL of MeOH/CHCl3 (4:1) containing 1 µM NaOH and analyzed by ESI-MS in the direct infusion mode at a flow rate of 3 µL/min. Samples were analyzed in the positive ion mode with detection of their sodiated adducts.

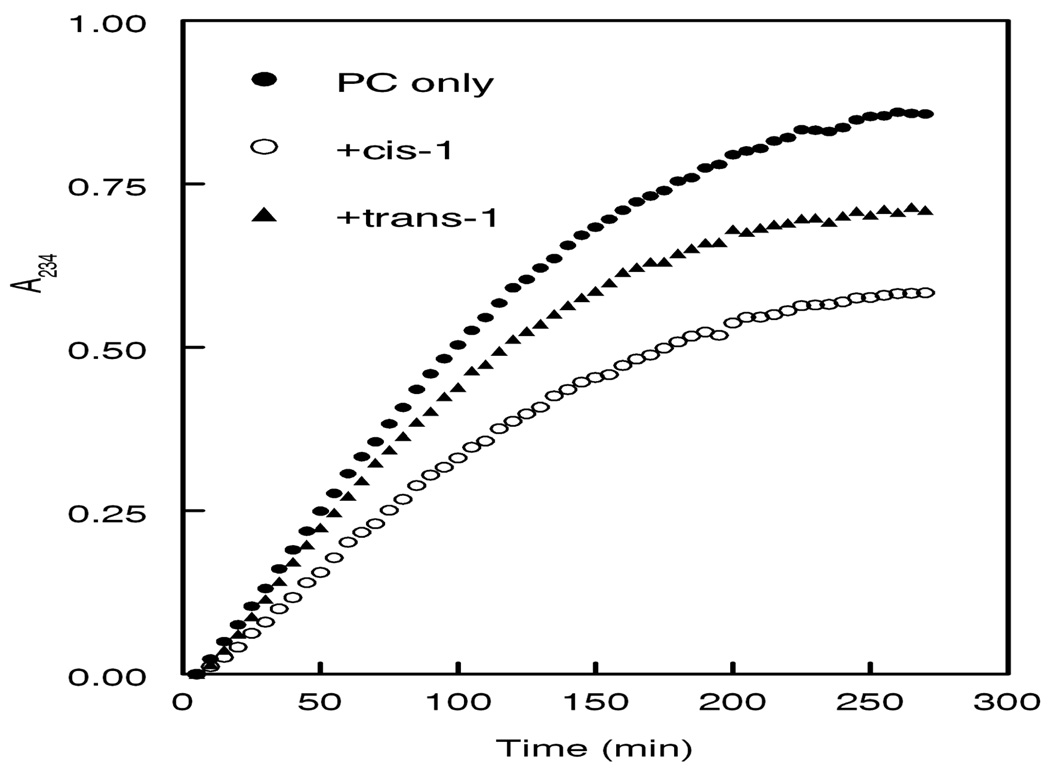

Plasmalogens are known to protect membrane phospholipids against radical-induced damage.1a Therefore, we next evaluated the ability of cis- and trans-1 to protect 16:0-18:2-PC from radical-mediated peroxidation in liposomes. The liposomes, which were prepared with 80 mol% 16:0-18:2-PC and 20 mol% cis- or trans-1, were subjected to oxidation by 3.3 mM AAPH. The oxidation of 16:0-18:2-PC26 was monitored by the increase in absorbance at 234 nm, a measure of conjugated diene hydroperoxide formation in the sn-2 fatty acyl group of PC.27 Figure 5 shows that cis-1 inhibited the rate of AAPH-mediated oxidation of 16:0-18:2-PC by 33% whereas trans-1 inhibited the rate by only 12%, based on the slopes of the reaction curves in the linear range (0–100 min). Similar data were obtained when 1 mM AAPH was used to induce oxidation (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of cis- and trans-1 on the oxidation of 16:0-18:2 PC induced by AAPH.

We also determined the effect of cis- and trans-1 on 16:0-18:2-PC oxidation in liposomes in the presence of 50 µM Cu2+ as the oxidizing agent, which facilitates free-radical chain propagation.28 We found that trans-1 was completely ineffective in protecting 16:0-18:2-PC oxidation whereas cis-1 inhibited PC oxidation by 45% (results not shown).

In summary, the first chemical synthesis of trans-1, an unnatural analog of plasmalogen bearing a trans O-vinyl linkage at the sn-1 position, has been achieved. A key step in the synthesis involves E stereoselective enol ether formation of 5 via an iridium(I)-mediated olefin isomerization of O-allyl ether 4. The kinetic data (Figure 3 and Figure 5) indicate that the geometry of the alkenyl ether linkage of plasmalogen plays a significant role in plasmalogen’s antioxidant properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants HL083187 (RB), HL088072 and HL074214 (DAF), and HL 68585 and DK 078165 (PVS).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and NMR spectra for the reported compounds. This material is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Footnotes

- 1.(a) Nagan N, Zoeller RA. Prog. Lipid Res. 2001;40:199–229. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brites P, Waterham HR, Wanders RJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1636:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horrocks LA, Sharma M. In: Phospholipids. Hawthorne JN, Ansell GB, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1982. pp. 51–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Morand OH, Zoeller RA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:11597–11606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoefler G, Paschke E, Hoefler S, Moser AB, Moser HW. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;88:1873–1879. doi: 10.1172/JCI115509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For examples of 1,2-dioxetane formation from the reaction of enol ethers with singlet oxygen, seeGollnick K, Knutzen-Mies K. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4017–4027.

- 5.(a) Engelmann B, Bräutigam C, Thiery J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;204:1235–1242. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jurgens G, Fell A, Ledinski G, Chen Q, Paltauf F. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1995;77:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(95)02451-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zommara M, Tachibana N, Mitsui K, Nakatani N, Sakono M, Ikeda I, Imaizumi K. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1995;18:599–602. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00155-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Reiss D, Beyer K, Engelmann B. Biochem. J. 1997;323:807–814. doi: 10.1042/bj3230807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hahnel D, Beyer K, Engelmann B. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999;27:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Maeba R, Ueta N. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:164–171. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200340-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zoeller RA, Lake AC, Nagan N, Gaposchkin DP, Legner MA, Lieberthal W. Biochem. J. 1999;338:769–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zoeller RA, Morand OH, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:11590–11596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stadelmann-Ingrand S, Favreliere S, Fauconneau B, Mauco G, Tallineau C. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2001;31:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Thompson DH, Inerowicz HD, Grive J, Sarna T. Photochem. Photobiol. 2003;78:323–330. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)078<0323:scoppp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loidl-Stahlhofen A, Hannemann K, Felde R, Spiteller G. Biochem. J. 1995;309:807–812. doi: 10.1042/bj3090807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofer G, Lichtenberg D, Kostner GM, Hermetter A. Clin. Biochem. 1996;29:445–450. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Subbaiah PV, Sircar D, Lankalapalli RS, Bittman R. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009;481:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Recknagel RO, Glende EA., Jr . In: Methods in Enzymology. Packer L, editor. Vol. 105. San Diego: Academic; 1984. pp. 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A semisynthetic route to racemic trans-1 via a lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of an 1-(alkenyloxy)-2,3-diacylglycerol was reportedSlotboom AJ, De Haas GH, van Deenen LLM. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1967;1:192–208.

- 11.(a) Klebanoff SJ. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2005;77:598–625. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Senthilmohan R, Kettle AJ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006;445:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:3271–3290. doi: 10.2174/092986706778773095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert CJ, Crowley JR, Hsu FF, Thukkani AK, Ford DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23733–23741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skaff O, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8237–8245. doi: 10.1021/bi800786q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messner MC, Albert CJ, Hsu FF, Ford DA. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2006;144:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2006.06.003.Primary amines react with HOCl to give chloramines; therefore, we synthesized plasmalogen with a phosphocholine head group instead of a phosphoethanolamine head group to target the O-vinyl ether linkage in the reaction with HOCl and avoid having a competing reactive site.

- 16.(a) Thukkani AK, Albert CJ, Wildsmith KR, Messner MC, Martinson BD, Hsu FF, Ford DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36365–36372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thukkani AK, Hsu FF, Crowley JR, Wysolmerski RB, Albert CJ, Ford DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3842–3849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Thukkani AK, Martinson BD, Albert CJ, Vogler GA, Ford DA. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H2955–H2964. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00834.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thukkani AK, McHowat J, Hsu FF, Brennan ML, Hazen SL, Ford DA. Circulation. 2003;108:3128–3133. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104564.01539.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Spickett CM. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niki E. In: Methods in Enzymology. Packer L, Glazer AN, editors. Vol. 186. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piantadosi CF, Hirsch AF, Yarbro CL, Anderson CE. J. Org. Chem. 1963;28:2425–2428.Craig JC, Hamon DPG. J. Org. Chem. 1965;30:4168–4175. doi: 10.1021/jo01023a044.Otera J, Niibo Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1986;59:3977–3978.Pfaendler HR, Müller FX. Synthesis. 1992:350–352.

- 20.Guivisdalsky PN, Bittman R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:3077–3079.Guivisdalsky PN, Bittman R. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4637–4642.

- 21.(a) Krompiec S, Kuźnik N, Urbala M, Rzepa J. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006;248:198–209. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuźnik N, Krompiec S. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007;251:222–233. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grieco PA, Nishizawa M, Marinovic N, Ehmann WJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:7102–7104. doi: 10.1021/ja00422a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Oltvoort JJ, Van Boeckel CAA, De Koning JH, Van Boom JH. Synthesis. 1981:305–308. [Google Scholar]; (b) Westcott SA. e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Z isomer of compound 5 was prepared by Lindlar reduction of an O-alkynyl ether; for the high-field doublet of the cis-O-vinyl proton, JH1’–H2’ = 6.20 Hz at δ 5.94 ppm.25

- 25.Qin DH, Byun HS, Bittman R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:662–668. [Google Scholar]

- 26.To correct for changes in A234 arising from AAPH-induced plasmalogen oxidation, liposomes were prepared with only cis- or trans-1 at the same concentrations present in the 16:0-18:2-PC + plasmalogen liposomes.

- 27.Esterbauer H, Striegl G, Puhl H, Rotheneder M. Free Radical Res. Commun. 1989;6:67–75. doi: 10.3109/10715768909073429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkitt MJ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;394:117–135. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.