Usually the determination of social ties follows a standardized procedure asking individuals who they consider a friend, approach for professional help, or communicate with on a regular basis. However, social ties are rather elusive to quantify, especially for a large sample of subjects over prolonged periods of time. As a direct consequence, investigated groups of subjects are usually small. Furthermore, data collection is restricted to mostly one time point, therefore collapsing all social activity into a static network of ties. Most social network studies heavily rely on such self-reports from study participants, data that obviously strongly suffer from cognitive biases, errors of perception, and ambiguities. Although important work has been published based on self-reported data, the ability to capture behavioral patterns is rather limited (1). However, the availability of digital communication datasets mitigates these initial problems. Because social networks are not static structures, the time resolution of such datasets allows an insight into the evolution and dynamics of social structures, prompting social theories about contacts, community, and consumption to be reexamined (2–8). For example, an analysis of e-mail logs from a major educational institution showed patterns of social ties as a function of existing social structure, shared activities, and personal attributes (6). The analysis of a large mobile phone call network revisited the quantification of previously rather elusive quantities such as weak and strong ties (9). Furthermore, such e-mail networks also allow the identification of a backbone that contributes to the fast dissemination of information (10). Even though such analysis furthered our understanding of webs of social ties profoundly, important questions remain unanswered. Observers have debated whether digital communications offer new methods of creating intimacy or are inflated measures of social connectedness that skim the surface of real attachments. Despite these important issues, little is known about whether electronic data indeed are a valid proxy for the real social connections they purportedly measure. Previous work has not scientifically addressed the level of agreement between actual social ties and electronic communication means. Specifically, social ties of individuals are multidimensional, maintaining a large portfolio of different types of (in)formal, professional, or romantic ties. For example, the utilization of e-mail logs alone captures only one channel of communication, thereby ignoring contacts that are maintained by different communication means (5). For example, individuals that share office space hardly will mutually exchange e-mails but will resort to communication in person. Furthermore, webs of social ties need to be considered from the perspective of a larger framework of collective social dynamics. In other words, the mutual interactions of individuals have consequences on the behavior of others (1).

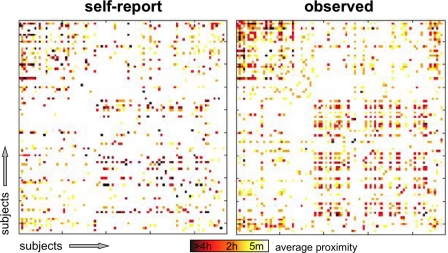

In this issue of PNAS, Nathan Eagle, Alex Pentland, and David Lazer (11) add a new dimension to the ongoing discussion of determining real friendship ties and networks. Although previous large-scale analyses used electronic footprint data as the sole source of behavioral information, Eagle, Pentland, and Lazer added a spatial component by equipping 94 students and faculty of a major research and educational institution with cell phones and tracking devices. Following the subjects over 9 months, rich information such as call logs, usage of the device, phone status, and accurate geographic proximity of subjects with an accuracy of a few meters was collected. An important question was the degree to which such electronically obtained data overlapped with self-reports. Previous research indicates that subjects tend to relate more to long-term than short-term social structures (12). Specifically, all subjects were asked about their typical proximity to the other individuals in the study, self-reports that were compared with the electronically obtained geographical proximity data. In general, the comparison of reported and observed proximity showed quite large differences (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, subjects that consider each other as friends were much more accurate in assessing their daily proximity than pairs of individuals who do not consider each other as friends. In particular, recent perception of proximity had a much more profound impact on self-reports, allowing Eagle, Pentland, and Lazer to conclude that the self-reported assessment of proximity not only has a recency bias but also a salience component.

Fig. 1.

Comparing the length of proximity, Eagle, Pentland, and Lazer (11) found significant differences in the self-reported assessment and the actually measured proximity between all pairs of subjects.

Spatial and temporal social context served as indicators of a friendship tie as well, considering that hours spent in geographic proximity away from the work environment are a strong indicator of a friendship tie. Applying a factor analysis showed that two separate factors play a decisive role in the spatial and temporal variability of the subjects. So-called “in-role” and “extra-role” factors, defined as behaviors typically associated with professional and more private/personal behavior, respectively, allowed a reliable prediction of (non)friendship ties. In conclusion, proximity data strongly reflect social and cultural norms, as has been reported in patterns of human mobility (13, 14).

Being the nemesis of predicting social ties, analyses of electronic datasets typically produce a lot of false-positives when compared with self-reported ties that, however, come with numerous problems of their own. Although spatial and temporal proximity data strongly indicate the presence of friendship ties, the perception of subjects appears to lag behind the underlying behavioral patterns. To compare the validity of these two measures of friendship relationships, self-reports and proximity data were used separately to predict social integration in work groups. Both models allowed Eagle, Pentland, and Lazer (11) to find that job satisfaction at the workplace is largely a matter of having friends in close proximity, whereas the lack of satisfaction is reflected by the propensity to call friends while at work. In conclusion, both sources of social information performed reasonably well, while electronically obtained data gained advantage in providing the better fits.

Proximity data strongly reflect social and cultural norms.

Eagle, Pentland, and Lazer (11) impressively demonstrate the utilization of modern telecommunication and tracking devices to contribute to social network research. They clearly show how disparate sources of information such as geographical proximity and call logs can be combined to assess the existence or absence of a social tie. Such data allowed the quantification of the discrepancy between the individual perception of a social relationship and the actual underlying behavior of individuals. Although this observation has been reported previously, their major contribution is the quantification of this observation by applying modern technologies. The approach demonstrates that the skillful integration and analysis of disparate data sources allows a better assessment of social ties than using one channel of communication alone, a concept that is currently applied on a large scale. As a consequence, the quantification of social ties will increasingly turn into a matter of collecting and skillfully integrating auxiliary information that can augment the assessment of a tie. Although the utilization of modern communication devices allows the time-resolved data collection from large groups of people, legal and privacy issues, however, might emerge because such information is mainly proprietary (15). On a different level, the combination of currently existing paradigms and novel automatic methodologies can provide novel insights into the collective behavior, cognitive constructs, social dynamics, and evolution of organizations and large communities. The identification and determination of such factors will contribute to a fundamental understanding of the forces that shape our communities, organizations, and society, ultimately allowing us to design successful and efficient work teams and collaborations.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 15274.

References

- 1.Watts DJ. A twenty-first century science. Nature. 2007;445:489. doi: 10.1038/445489a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baym NK, Zhang YB, Lin MC. Social interactions across media. New Media Society. 2004;6:299–318. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malmgren RD, Stouffer DB, Motter AE, Amaral LA. A Poissonian explanation for heavy tails in e-mail communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18153–18158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800332105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guimera R, Uzzi B, Spiro J, Amaral LA. Team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science. 2005;308:697–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1106340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menchik DA, Tian X. Putting social context into text: The semiotics of e-mail interaction. Am J Sociol. 2008;114:332–370. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kossinets G, Watts DJ. Empirical analysis of an evolving social network. Science. 2006;311:88–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1116869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palla G, Barabasi A-L, Vicsek T. Quantifying social group evolution. Nature. 2007;446:664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature05670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salganik MJ, Dodds PS, Watts DJ. Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science. 2006;311:854–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1121066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onnela JP, et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610245104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kossinets G, Kleinberg J, Watts DJ. The structure of information pathways in a social communication network. In: Li Y, Liu B, Sarawagi S, editors. KDD 2008. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2008. pp. 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eagle N, Pentland A, Lazer D. Inferring friendship network structure using mobile phone data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15274–15278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900282106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman L, Romney A, Freeman S. Cognitive structure and informant accuracy. Am Anthropol. 1987;89:310–325. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez MC, Hidalgo CA, Barabasi A-L. Understanding individual human mobility patterns. Nature. 2008;453:779–782. doi: 10.1038/nature06958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brockmann D, Hufnagel L, Geisel T. The scaling laws of human travel. Nature. 2006;439:462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature04292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazer D, et al. Computational social science. Science. 2009;323:721–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1167742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]