Abstract

Early life trauma alters later life emotions, including fear. To better understand mediating mechanisms, we subjected pups to either predictable or unpredictable trauma, in the form of paired or unpaired odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning which, during a sensitive period, produces an odor preference and no learning respectively. Fear conditioning and its neural correlates were then assessed after the sensitive period at postnatal day (PN)13 or in adulthood, ages when amygdala-dependent fear occurs. Our results revealed that paired odor-shock conditioning starting during the sensitive period (PN8–12) blocked fear conditioning in older infants (PN13) and pups continued to express olfactory bulb-dependent odor preference learning. This PN13 fear learning inhibition was also associated with suppression of shock-induced corticosterone, although the age appropriate amygdala-dependent fear learning was reinstated with systemic corticosterone (3 mg/kg) during conditioning. On the other hand, sensitive period odor-shock conditioning did not prevent adult fear conditioning, although freezing, amygdala and hippocampal 2-DG uptake and corticosterone levels were attenuated compared to adult conditioning without infant conditioning. Normal levels of freezing, amygdala and hippocampal 2-DG uptake were induced with systemic corticosterone (5 mg/kg) during adult conditioning. These results suggest that the contingency of early life trauma mediates at least some effects of early life stress through learning and suppression of corticosterone levels. However, developmental differences between infants and adults are expressed with PN13 infants' learning consistent with the original learned preference, while adult conditioning overrides the original learned preference with attenuated amygdala-dependent fear learning.

Keywords: odor, infant, learning, sensitive period, attachment, amygdala, hippocampus, fear conditioning

Introduction

Early life maltreatment and stress influence the normal development of neural systems – more particularly the amygdala and the hippocampus – and are associated with both infant and adult mental health vulnerability (Glaser, 2000; Grossman et al., 2003; Teicher et al., 2003; Hammock and Levitt, 2006; Gunnar and Quevedo, 2007). Indeed, early life trauma alters the fear system causing aberrant fear responses associated with psychiatric disorders, including increased fear expression in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) but decreased fear expression in psychopathy (Kiehl et al., 2001; Sheline et al., 2001; Drevets, 2003; Bremner et al., 2005). Furthermore, the stress system, a critical mediator of early life stress on later life compromised mental heath, is also altered (Glaser, 2000; Grossman et al., 2003; Teicher et al., 2003; Gunnar and Quevedo, 2007). This association between early life trauma/stress, limbic system development and disrupted behavioral outcome has been modeled in animals, which suggests a causal relationship (Dent et al., 2001; Sanchez et al., 2001; Plotsky et al., 2005; Akers et al., 2006; Champagne et al., 2008; Cirulli et al., 2009).

How early trauma alters the amygdala or hippocampus programming during development is not completely understood. Therefore, we explored mechanisms involved in this process using odor-0.5 mA shock learning as a model of early life maltreatment and explored how it affects rat infants and adult fear learning and associated neural circuitry. During the infant rat sensitive period (until postnatal day 10, PN10), odor-0.5 mA shock produces an odor preference similar to an odor paired with stimuli such as milk, warmth or tactile stimulation (Haroutunian and Campbell, 1979; Brake, 1981; Pedersen et al., 1982; Sullivan et al., 1986a,b, 1990; Camp and Rudy, 1988) using a learning circuit that incorporates the olfactory bulb and anterior piriform of the olfactory cortex (Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004; Roth and Sullivan, 2005; Moriceau et al., 2006). However, infant odor preference learning with painful stimuli such as shock also requires amygdala suppression (Sullivan et al., 2000; Roth and Sullivan, 2005; Moriceau and Sullivan, 2006; Moriceau et al., 2006), which is normally activated by pain and is required for the odor-shock fear conditioning seen in adults and older pups (LeDoux, 2000; Schettino and Otto, 2001; Fanselow and Gale, 2003; Maren, 2003; Sevelinges et al., 2004, 2007; Rattiner et al., 2005; Debiec and LeDoux, 2006; Sigurdsson et al., 2007). Indeed, the amygdala's failure to be recruited during odor-shock conditioning in pups may ensure that infants maintain a preference for the neonatally learned maternal odor despite potentially harsh treatment from their mother. This paradoxical infant odor-shock induced odor preference has consequences in adulthood, as this learning attenuates adult fear conditioning and is associated with changes in amygdala processing as revealed by decreased paired-pulse inhibition in adulthood (Sevelinges et al., 2007, 2008). Altricial infant animals from other species, such as chicks, rodents, nonhuman primates and humans, have shown a similar predisposition to approach the caregiver despite maltreatment (Hess, 1962; Stanley, 1962; Bowlby, 1965, 1969; Harlow and Harlow, 1965; Hinde and Spencer-Booth, 1967; Salzen, 1970; Hinde, 1991; Helfer et al., 1997; Maestripieri et al., 1999; Sanchez et al., 2001; Roth and Sullivan, 2005; Suomi, 2006). Indeed, even within the format of learning, infant dogs and chicks learn to approach the caregiver (Stanley, 1962; Salzen, 1970; Sullivan et al., 1990; Roth and Sullivan, 2005).

Our previous work has highlighted the critical role of low corticosterone (CORT) during odor-shock conditioning for pup odor preference learning and suppression of amygdala plasticity. Specifically, manipulation of CORT levels can act as a switch to determine whether infants learn an aversion or a preference from odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning (Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004; Moriceau et al., 2006). For example, increasing CORT (systemic, intra-amygdala) during odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning is sufficient to elicit amygdala-dependent fear learning in the sensitive period, while lowering CORT in older animals switches fear learning to preference learning (Moriceau and Sullivan, 2006; Moriceau et al., 2006). This is in sharp contrast to CORT effects in adults where CORT modulates fear conditioning and inhibitory conditioning, but does not switch learning from aversion to preference (Corodimas et al., 1994; Pugh et al., 1997; Roozendaal, 2002; Hui et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2004).

Here, we use an infant rat odor-0.5 mA shock fear conditioning procedure as a model of early life maltreatment and explore potential consequences on infant and adult fear learning and associated neural circuitry.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1: Experience with sensitive period odor-shock conditioning maintains the odor preference and blocks fear learning

Subjects

The subjects were 60 male and female Long Evans rat pups born in the University's vivarium. No more than one male and one female were used per litter for a given experimental treatment. Dams were housed in rectangular polypropylene cages with abundant wood chips in a temperature (23°C) and light (08:00–20:00 hours) controlled room. Ad libitum food and water were always available. Births were checked daily with litters culled to 12 pups, 6 males and 6 females at PN1. Pups were kept from the mother for approximately 1 h for conditioning. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed NIH guidelines.

Odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning

Pups were conditioned for 2 (PN8–9), 3 (PN8–10), 4 (PN8–11) or 5 (PN8–12) consecutive days always beginning at PN8. Each conditioning session lasted 45 min, with pups receiving 11 presentations of a 30-s citral odor (conditioned stimulus, CS) and a 1-s 0.5 mA tail shock (unconditioned stimulus, US; LaFayette), with an intertrial interval of 4 min. The odor was delivered by a flow dilution olfactometer (2 L/min flow rate) at concentration of 1:10 odor vapor. Pups were assigned to one of the two following conditioning groups: Paired odor-0.5 mA shock pups received a shock overlapping with the last second of the 30 s odor presentation and Odor Only pups received only the odor presentations. Pups were returned to the nest immediately following conditioning.

Behavioral testing for odor preference or aversion: Two-odor choice test

Approximately 24 h after the last conditioning session (PN10, 11, 12 or 13), learning was assessed with a two-odor choice test comparing pups’ responses to the CS odor vs. familiar clean wood shavings (same type used in the nest for bedding). Between the three testing trials, pups were placed in a holding cage for 5 s while the floor was wiped clean with water and dried. Individual pups were tested only once (e.g., at a single age). A video tracking system (Columbus Instruments) was used to monitor pups’ behavior. Testing was done blind to the conditioning groups.

The testing apparatus was an opaque Plexiglas box with a wire mesh floor as previously described (Sullivan et al., 1989). The CS odor was placed under one half of the box and the familiar wood odor placed under the other half. Pups were given 3 one-min trials, which began by placing a pup in a neutral zone between the two odors. A response was considered a choice when a pup's entire body moved beyond the neutral zone.

Experiment 2: Neurobehavioral effects of early life experience with odor-shock conditioning and corticosterone (CORT) manipulation

Subjects

This experiment used 123 male and female Long-Evans rat pups with housing similar to that used in experiment 1.

Odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning

The odor-shock conditioning procedure used here was similar to that used in experiment 1, with the following differences: (1) a different odor was used: peppermint (same delivery procedure as described in the first experiment), (2) for the CS, pups were given a 0.5-mA foot shock rather than a 0.5-mA tail shock, (3) an additional learning control group was added (Unpaired odor-shock presentations where pups received the shock 2 min after each odor presentation) and (4) the ages of conditioning were limited to PN8–11. From PN8–11, pups received four consecutive days of conditioning (Paired, Unpaired, Odor Only and Naïve; Figure 1). At PN12, the Paired group received Paired conditioning without (Infant Paired/PN12 Paired) or with CORT injection (Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT; 3.0 mg/kg, ip), the Naïve group received Paired conditioning (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired), the Unpaired group received Unpaired conditioning (Infant Unpaired/PN12 Unpaired), and the Odor Only group received Odor Only conditioning (Infant Odor Only/PN12 Odor Only).

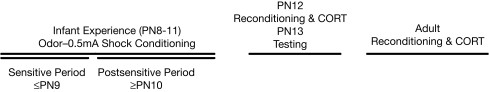

Figure 1.

Infant rat pups experienced 4 consecutive days of odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning initiated during the sensitive period at PN8 but continued during the postsensitive period (≥PN10). Animals were reconditioned at PN12 or in adulthood, with or without a systemic injection of CORT. Immediately after conditioning, brains were removed for 14C 2-DG assessment or animals returned to the home cage for behavioral testing the next day.

Systemic CORT injections

Some pups received a control (saline) or a CORT injection (Corticosterone HBC complex, Sigma; 3.0 mg/kg dissolved in saline, ip) 30 min prior to the last day of conditioning at PN12, which allowed CORT to be present during the conditioning. Doses were chosen following dose-response established previously and pilot data (Takahashi, 1994; Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004, 2006; Moriceau et al., 2006).

CORT radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Blood CORT levels were measured at PN8 and PN12, immediately following conditioning. Duplicate plasma samples were analyzed for CORT using the Rat corticosterone Coat-a-Count Kit (Radioassay Systems Labs, In., Carson, CA). The sensitivity of the assay was 5 ng/ml. The intraassay coefficient of variation was 1–9%. Heart blood samples were taken from pups immediately after the conditioning session, centrifuged at 14,000 cpm for 6 min, the plasma aliquoted and stored at −70°C for later analysis.

Behavioral testing for odor preference or aversion: Y-maze test

Learning was assessed with a Y-maze on PN13. The Y-maze consisted of a start box (8.5 cm width, 10 cm length, 8 cm height) and two arms (8.5 × 24 × 8 cm) separated by two doors. This test required pups to choose between two arms of a Plexiglas Y-maze, one containing the CS odor and the other containing the familiar wood odor (20 ml of clean shaving in a petri dish). To initiate a trial, a pup was placed in the start box for 5 s, the doors to each arm were opened and the pup was given 60 s to choose an arm. A response was considered a choice when a pup's entire body moved beyond the entrance to the alley. Pups received five trials and were removed to a holding chamber for 5 s between trials while the Y-maze floor was wiped clean. No CORT was injected for testing. Testing was done blind to the conditioning groups.

Conditioning and 14C 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) autoradiography

Pups were assessed for activation of brain areas previously shown to be involved in infant odor preference learning (olfactory bulb) and older pup/adult fear conditioning (amygdala basolateral complex and hippocampus) during odor-shock conditioning.

Pups were injected with 14C 2-DG (20 μCi/100 g) 5 min prior to training for assessment during the last conditioning session (PN12). The brain was removed immediately following conditioning and quickly frozen in 2-methylbutane at −45°C. The frozen brain was then stored in −70°C freezer and equilibrated to −20°C in a cryostat prior to preparation of 20 μm coronal sections that were warmed at 60°C for 5–10 min. A set of 14C labeled methyl methacrylate standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals), previously calibrated to 14C uptake in 20 μm brain sections, was exposed with each sheet of film and developed using standard techniques (Sullivan et al., 1989). The autoradiographs were analyzed using a computer-based digital image processor and NIH Image Software that allows pseudocolor imaging and quantitative optical densitometry. The olfactory bulb is readily identifiable for 2-DG uptake assessment. Odors produce an odor-specific pattern of 2-DG uptake within the glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb, which is enhanced with neonatal odor conditioning (Lancet et al., 1982; Coopersmith and Leon, 1986; Sullivan and Leon, 1986). However, the amygdala and the hippocampus required counterstaining sections with cresyl violet and construction of a template of that brain area for use on the autoradiographs to identify specific nuclei and subareas. To control the potential differences in section thickness and autoradiograph exposure, 2-DG uptake was measured relative to 2-DG uptake in the corpus callosum (amygdala, hippocampus) or the olfactory bulb's periventricular core, areas that did not vary with conditioning group (Sullivan and Leon, 1986; Sullivan et al., 2000).

Since pups used for autoradiography were not tested, we used a behavioral rating scale (Johanson and Hall, 1979) to document acquisition curves in response to the CS odor compared to activity immediately preceding odor onset, which allowed monitoring of pups’ acquisition of learned responses: 0 – not active; 1 – movement of 1 body part (i.e., head rearing); 2 – movement of 2 body parts; 3 – movement of 3 body parts; 4 – movement of 4 body parts; 5 – movement of 5 body parts (i.e., locomotion).

Experiment 3: Neurobehavioral effects of early life experience on adult odor-shock conditioning and CORT manipulation

Subjects

This experiment used 80 male Long Evans rats from 3- to 4-month old.

Adult odor-shock conditioning

Rats were conditioned in infancy as described above (Figure 1) and again conditioned in adulthood. The adult conditioning used a protocol similar to infant conditioning, although the shock was slightly higher (0.8 mA, 1 s foot shock delivered through a grid floor). The adult rat was placed in the conditioning chamber 10 min before beginning the conditioning session, and a 30-s citral CS was delivered with the shock occurring during the last second of the odor with a 4 min ITI (same delivery procedure as described in experiment 1). The odor was also delivered by a flow dilution olfactometer at the same concentration used in infancy (1:10 peppermint vapor to air; 1 L/min flow rate). Conditioning took place in a standard conditioning chamber attached to a shock generator (LaFayette) within a ventilated attenuating chamber under red light and peppermint used as context. Rats were handled three times for 5 min in the week preceding conditioning. In general, animals were placed in the same conditioning group for infant and adult conditioning: (1) Infant Paired/Adult Paired, (2) Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT (5.0 mg/kg, ip only during adult conditioning), (3) Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, (4) Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired and (5) Infant Odor Only/Adult Odor Only.

The infant/adult conditioning groups were chosen based on previous work where all configurations of infant/adult conditioning were used (Sevelinges et al., 2007). We found that infant odor conditioning attenuated adult fear conditioning and amygdala 2-DG uptake if the same CS odor was used in infancy and adulthood, or the infant odor was present as context during adult conditioning with a novel odor CS.

Systemic CORT injections

The Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT group rats received a CORT injection (5.0 mg/kg, ip) immediately before adult conditioning, which allowed CORT to be present during conditioning (Sandi et al., 1995; Roozendaal et al., 2006).

Cue testing in adulthood

CS conditioned fear was assessed 24 h after the adult odor-shock conditioning in a novel test chamber to prevent context fear conditioning influences. The cue-testing chamber was a Plexiglas aquarium (25.4 × 50.8 × 30.5 cm). Rats were placed in the testing chamber and given 10 min to recover from experimenter handling before testing began. The 30-s citral odor was then introduced three times with an ITI of 4 min. Freezing behavior, characterized by a crouching posture and an absence of any visible movement, except that due to breathing, was assessed for 30 s before and 30 s during each odor presentation. Testing was done blind to the conditioning groups.

Behavioral testing for odor preference or aversion: Y-maze test

Retention of infant learning was also assessed with a Y-maze test in adulthood (these rats were not used for adult conditioning experiments). The Y-maze consisted of a start box (13 cm width, 18 cm length, 18 cm height) and two arms (13 × 65 × 18 cm) separated by two doors. This test required rats to choose between two arms of a Plexiglas Y-maze, one containing the CS odor and the other containing the familiar wood odor (20 ml of clean shaving in a petri dish). To initiate a trial, the adult rat was placed in the start box for 5 s, the doors to each arm were opened and the animal was given 60 s to choose an arm. Rats received three trials and were removed to a holding chamber for 5 s between trials while the Y-maze floor was wiped clean. Testing was done blind to the conditioning groups.

Conditioning for 14C 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) autoradiography

Adult rats were injected with 14C 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 40 μCi ip/rat) 5 min prior to the 45-min adult odor-shock conditioning. Immediately following conditioning, adult rats were decapitated and their brains quickly removed, frozen in 2-methylbutane (−45°C) and stored in a −70°C freezer. The analysis was similar to that used in Experiment 2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were analyzed by ANOVA followed by posthoc Fisher tests. Posthoc tests indicated that the experimental groups were different from each of the control groups at the 0.05 level or below. Significance between groups is noted by asterisks in the figures.

Results

Experiment 1: Experience with sensitive period odor-shock maintains the odor preference and blocks fear learning in pups

This experiment assessed whether extended, daily conditioning initiated during the sensitive period (PN9 is the last day of odor-shock preference learning) could switch the preference learning to odor aversion learning if the conditioning was continued in postsensitive period pups (PN10 and older). That is, would the continued conditioning in older pups over-write the original learned preference with a learned aversion?

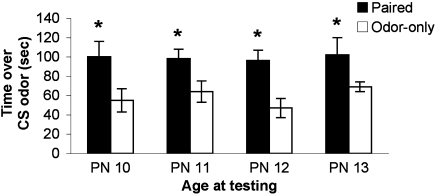

Beginning at PN8, pups were odor-0.5 mA shock conditioned for 2 (PN8–9), 3 (PN8–10), 4 (PN8–11), or 5 (PN8–12) days and tested the day following the last conditioning session (PN10, 11, 12 or 13; pups were eliminated from the experiment after testing). As illustrated in Figure 2, pups retain and express a learned odor preference despite considerable conditioning during a developmental stage when pups could learn an aversion (see Experiment 2 and Figure 3; ANOVA main effect of group, F(1,52) = 17.74, p < 0.001; posthoc Fisher tests revealed a significant difference between Paired and Odor Only pups at the p < 0.01 level at all ages). Thus, once the association between odor and shock is made early in development, subsequent associations in infancy reinforce the original learned behavior – i.e. conditioned approach response – rather than over-writing with an age appropriate memory.

Figure 2.

Pups were odor-0.5 mA shock conditioned for 2 (PN8–9), 3 (PN8–10), 4 (PN8–11) or 5 (PN8–12) consecutive days and tested during the postsensitive period on either PN10, PN11, PN12 or PN13, which are ages when amygdala-dependent fear conditioning can occur (n = 7–8/group). The result is expressed as cumulative data from the three testing trials. All experimental Paired odor-shock pups continued to exhibit a relative preference to the conditioned odor despite continued odor-shock conditioning following the termination of the sensitive period. Each pup was tested only once. Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

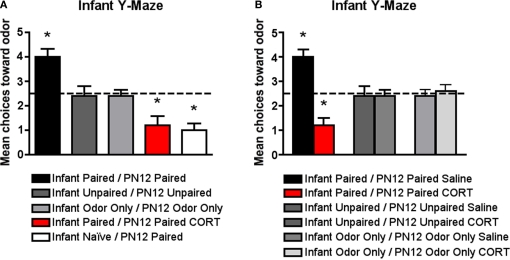

Figure 3.

Pups were conditioned daily from PN8 to PN12 (replicates PN13 test data in Figure 2) or conditioned only on PN12 (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired), which previous results have shown are capable of amygdala-dependent fear and aversion learning (Sullivan et al., 2000). All pups were tested on PN13 in a Y-maze to assess odor preference/aversion learning. (A) Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired odor-0.5 mA pups demonstrated an aversion, while Infant Paired/PN12 Paired odor-0.5 mA pups showed a preference for the conditioned odor compared to controls (n = 5/group). However, systemically injecting Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups with 3 mg/kg CORT during the last day of odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning (PN12) permitted odor aversion learning. These behavioral groups are littermates of the 2-DG pups presented in Figure 5. (B) Additional control injection groups are presented here. Systemically injecting Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups with saline during the last day of odor-0.5 mA shock conditioning (PN12) still permitted odor preference learning while injecting Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups with 3 mg/kg CORT permitted odor aversion learning compare to control groups (n = 6/group). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

Experiment 2: Neurobehavioral effects of early life experience with odor-shock conditioning and CORT manipulation in pups

We hypothesized that prolonged odor-shock conditioning suppressed shock-induced CORT release in amygdala-dependent fear conditioning in pups. This was done by assessing: (1) whether early life experience with odor-shock attenuates shock-induced CORT release (blood RIA) and (2) whether we could systematically inject CORT to override CORT suppression and permit amygdala-dependent fear conditioning. This design is illustrated in Figure 1. CORT injected during conditioning is no longer present during testing (Goodman and Gilman, 1985).

Behavioral analysis

The data illustrated in Figure 3A replicates the 5 days of odor-shock conditioning shown in Figure 2 but has additional control groups and illustrates that Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired pups (receiving Paired odor-shock conditioning for the first time at PN12) learn an odor aversion as indicated by the Y-maze test at PN13, while the Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups learn an odor preference (Sullivan et al., 2000; Moriceau et al., 2006). Furthermore, as seen in Figures 3A,B, Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups, which received a CORT injection for the last conditioning session (PN12), permitted odor aversion learning as indicated by the Y-maze test at PN13 while the Infant Paired/PN12 Paired saline still learned an odor preference. Furthermore, control injection with saline did not affect learning, while CORT injection only affected the learning of paired groups. Figure 3A ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect of conditioning groups [F(5,28) = 18.599, p < 0.0001] and Figure 3B ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect of group drugs [F(1,24) = 11.655, p < 0.0001] and a significant interaction between conditioning groups and drugs [F(2,24) = 14.552, p < 0.0001]; posthoc Fisher tests indicated that Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups were statistically different from both the Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups at the p < 0.05 level. Additionally, Infant Paired/PN12 Paired, Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT groups were each statistically different from the non-associative control groups at the p < 0.05 level. Furthermore, posthoc Fisher tests indicated that Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired Saline pups were statistically different from the non-associative control groups and from each other at the p < 0.05 level.

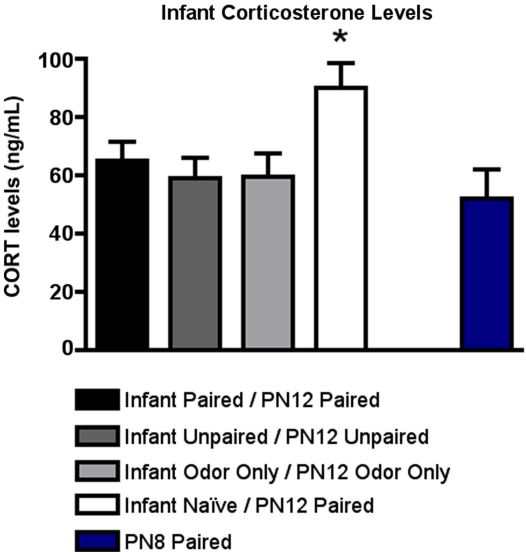

As illustrated in Figure 4, CORT levels immediately following PN12 conditioning showed that Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired pups mounted a robust CORT response to shock that was absent in the Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups. For comparison, we also included sensitive period pups (PN8 Paired) because it is an age when shock does not produce a CORT increase (Levine, 2001). ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect of conditioning groups [F(4,20) = 3.141, p < 0.05]; posthoc Fisher tests showed that Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired pups at PN12 had significantly more plasma shock-induced CORT than each of the other groups at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 4.

RIA measurement from pups immediately following odor-shock conditioning indicates that CORT levels increased only in Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired pups receiving odor-shock conditioning for the first time during the postsensitive period (PN12) (n = 5–7/group). All other groups, including the Infant Odor Only/PN12 Odor Only group that did not receive shocks, show levels of CORT similar to PN8 Paired pups (still in the Stress Hyporesponsive Period; SHRP). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

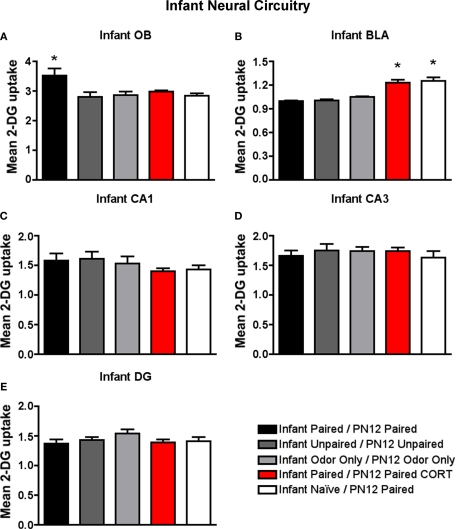

Neural analysis

As illustrated in Figure 5, Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups maintained elevated 2-DG uptake in the infant attachment learning circuit (olfactory bulb) but prevented an increase in 2-DG uptake in the fear circuit (amygdala basolateral complex). On the other hand, Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups prevented 2-DG uptake in the attachment circuit and instead showed elevated 2-DG uptake in the fear circuit (amygdala basolateral complex).

Figure 5.

14C 2-DG autoradiography was used to assess brain areas previously shown to be important for either early life attachment/preference learning (olfactory bulb) or avoidance/fear learning (amygdala). These data compliment behavioral data in Figure 3. Pups were trained daily from PN8–12 or conditioned only on PN12 (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired) (n = 5–7/group). 2-DG autoradiography during the last odor-shock conditioning session on PN12 showed that (A) Infant Paired/PN12 Paired odor-shock pups exhibit activation in the odor-specific loci of the olfactory bulb (OB) compared to Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired pups that we conditioned only on PN12, (B) Pups receiving odor-shock conditioning for the first time (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired) or after five sessions but given a PN12 CORT injections (Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT) showed increase 2-DG uptake of the amygdala's basolateral complex (BLA), and no statistical differences in 2-DG uptake were found for hippocampal subareas: CA1 (C), CA3 (D) and DG (E). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

Specifically, as shown in Figure 5A, Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups have an increased 2-DG uptake in the odor-specific loci of the olfactory bulb [ANOVA, F(4,24) = 3.754, p < 0.05] compared to Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups. The periventricular core of the olfactory bulb did not show any difference between conditions. Posthoc Fisher tests indicated that the Infant Paired/PN12 Paired group differed significantly from each of the other groups at the p < 0.05 level.

As shown in Figure 5B, Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT pups show a significant increase in 2-DG uptake in the amygdala basolateral complex [ANOVA, F(4,26) = 31.814, p < 0.0001] compared to Infant Paired/PN12 Paired and control pups. Posthoc Fisher tests indicated that the Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired and Infant Paired/PN12 Paired CORT groups significantly differed from each of the other conditioning groups at the p < 0.05 level.

No statistical differences in 2-DG uptake were detected in any hippocampus subareas (CA1, CA3 and DG).

Experiment 3: Neurobehavioral effects of early life experience on odor-shock conditioning in adults

We hypothesized that prolonged infant odor-shock conditioning suppressed shock-induced CORT release in amygdala-dependent fear conditioning in adult. Our previous work had shown that early life experience with odor-shock attenuates adult conditioning (Sevelinges et al., 2007, 2008). Here we assessed whether (1) early life experience with odor-shock attenuates shock-induced CORT release (blood RIA) in adults and (2) whether we could systematically inject CORT to override CORT suppression and permit amygdala-dependent fear conditioning in adults. This design is illustrated in Figure 1. CORT injected during conditioning is no longer present during testing (Goodman and Gilman, 1985).

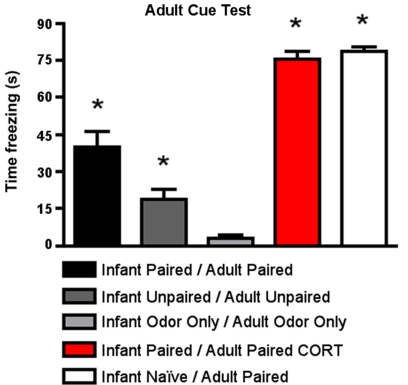

Behavioral analysis

As shown in Figure 6, for cue testing, Infant Paired/Adult Paired animals demonstrated low levels of freezing, although a CORT injection during adult conditioning (Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT) increased freezing during the cue test to levels exhibited by adults conditioned for the first time (Infant Naïve/Adult Paired). ANOVA analysis revealed a main effect of condition [F(4,23) = 77.658, p < 0.0001]; posthoc Fisher tests revealed that the Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT, which were not statistically different from one another, both differed significantly from all the control groups and Infant Paired/Adult Paired at the p < 0.05 level. The Infant Paired/Adult Paired group was significantly different from all other groups at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 6.

Adult rats were reconditioned after the infant conditioning, generally using the same conditioning group in infancy and adulthood. All rats were tested the next day to measure freezing following exposure to the citral CS used in adult conditioning. Infant Paired/Adult Paired demonstrated lower levels of freezing than Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Paired/Adult Paired receiving a CORT injection (n = 4–5/group). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

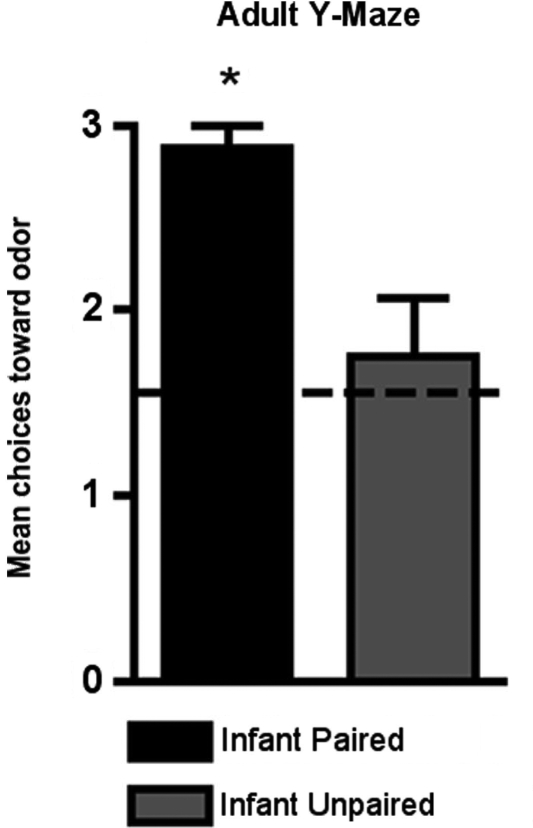

As shown in Figure 7, adult rats retained the odor preference from infant odor-shock conditioning as indicated by the Y-Maze test. Specifically, adult rats with infant odor-shock conditioning were significantly different from animals with infant unpaired odor-shock conditioning [t(1,14) = 11.118, p < 0.005].

Figure 7.

Adult rats were tested in a Y-maze following infant odor-shock conditioning to assess whether the odor preference was retained into adulthood. The Infant Paired/Adult Naïve rats demonstrated a preference compared to the Infant Unpaired/Adult Naïve control group (n = 7–8/group). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

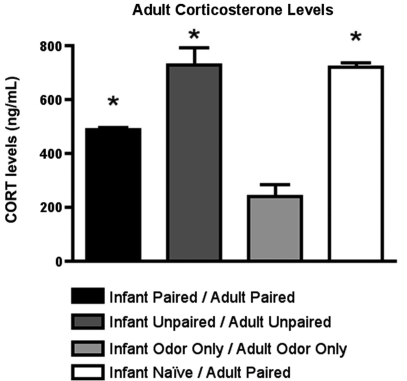

Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 8, CORT levels immediately following adult conditioning showed that odor-shock conditioning for the first time (Infant Naïve/Adult Paired) produced a robust shock-induced CORT release. A similar level of CORT was mounted by animals that had received both infant and adult unpaired shock (Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired), while the Infant Paired/Adult Paired group showed attenuated shock-induced CORT release. ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect of conditioning groups [F(3,11) = 38.745, p < 0.001]; posthoc Fisher tests showed that Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired rats had significantly more plasma CORT than all other groups at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 8.

RIA measurement from adult rats immediately following odor-shock conditioning indicates that CORT levels increased in Infant Naïve/Adult Paired groups (n = 4–5/group) and control. The Infant Odor Only/Adult Odor Only group that did not receive shocks, show low levels of CORT. Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

Neural analysis of the attachment circuit

As shown in Figure 9A, only animals that experienced both infant and adult paired odor-shock (Infant Paired/Adult Paired) exhibited increased 2-DG uptake in the odor-specific loci of the olfactory bulb [ANOVA, F(4,13) = 7.897, p < 0.005]. Posthoc Fisher tests indicated that the Infant Paired/Adult Paired group significantly differed from each of the other conditioning groups at the p < 0.05 level. That is, adult experience with paired odor-shock did not alter the infant learning-induced changes within the olfactory bulb. Thus, Infant Paired/Adult Paired, which exhibited freezing during testing, albeit attenuated, showed activation of the attachment circuit and not the fear circuit. This replicates our previous work (Sevelinges et al., 2007, 2008).

Figure 9.

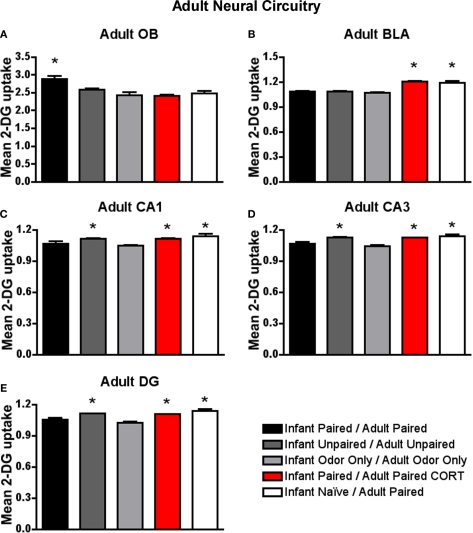

Adult rats were reconditioned after the infant conditioning, generally using the same conditioning group in infancy and adulthood. 14C 2-DG autoradiography during the adult odor-shock conditioning session showed that (A) Infant Paired/Adult Paired animals exhibit activation in the odor-specific loci of the olfactory bulb (OB) compared to Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT injection and Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, (B) Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT injection both show increased 2-DG uptake in the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA), and Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT injection and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired groups show increase 2-DG uptake in the CA1 (C), CA3 (D) and DG (E). Asterisk represents a significant difference from each of the other groups (p < 0.05).

Neural analysis of the fear circuit

As shown in Figure 9B, Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT, (CORT during adult conditioning only) showed a significant increase in 2-DG uptake of the basolateral complex of the amygdala [ANOVA, F(4,14) = 36.042, p < 0.0001] compared to Infant Paired/Adult Paired group and control pups. Posthoc Fisher tests indicate that the Infant Naïve/Adult Paired and Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT groups significantly differed from each of the other conditioning groups at the p < 0.05 level. Thus, the injection of CORT for the Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT group brought freezing to normal levels, as well as switched the olfactory bulb enhanced 2-DG to enhanced amygdala 2-DG.

Our hippocampus analysis indicates that Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired expressed increased 2-DG uptake in hippocampus subareas CA1 (Figure 9C), CA3 (Figure 9D) and DG (Figure 9E). Indeed, Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired showed a significant 2-DG uptake increase in the CA1 [ANOVA, F(4,13) = 5.534, p < 0.01], CA3 [ANOVA, F(4,13) = 7.669, p < 0.01] and DG [ANOVA, F(4,13) = 16.0602, p < 0.0001]. Posthoc Fisher tests indicated that the Infant Naïve/Adult Paired, Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired groups significantly differed from each of the other conditioning groups at the p < 0.05 level. Thus, Infant Paired/Adult Paired, which exhibited freezing during testing, albeit attenuated, showed atypical activation of the attachment circuit (olfactory bulb) but not the amygdala and hippocampus of the fear circuit. Furthermore, the injection of CORT for the Infant Paired/Adult Paired CORT group was able to bring freezing to normal levels, as well as switch the atypical olfactory bulb enhanced 2-DG to the typical enhanced amygdala and hippocampal 2-DG.

Discussion

These data suggest that early life Paired odor-shock conditioning modifies learning and the associated neural circuit and these changes are mediated through CORT suppression. Specifically, prolonged odor-shock conditioning initiated during the sensitive period (Infant Paired/PN12 Paired) continues to activate the odor preference learning circuit in PN13 pups, attenuates the shock-induced CORT increase and blocks amygdala-dependent fear learning, which normally occurs at this age (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired; Figures 3–5). Conversely, this infant Paired odor-shock conditioning did not prevent adult fear conditioning, although fear learning, amygdala and hippocampal 2-DG uptake and CORT levels were attenuated (Infant Paired/Adult Paired) compared to adult conditioning without infant experience (Infant Naïve/Adult Paired; Figures 6, 8 and 9). This is consistent with our previous work, which showed that when conditioned for the first time, postsensitive period pups (≥PN10) appear similar to adults, with both groups showing robust amygdala-dependent fear conditioning (LeDoux, 2000; Sullivan et al., 2000; Fanselow and Gale, 2003; Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004, 2006; Roth and Sullivan, 2005; Moriceau et al., 2006; Sevelinges et al., 2007; Sigurdsson et al., 2007; Raineki et al., 2009b).

The Infant Unpaired/PN12 Unpaired group did not show learning in infancy. However, the Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired showed some increases in freezing, hippocampal 2-DG uptake and shock-induced CORT release, although levels of amygdala 2-DG uptake were similar to those seen in other controls. While the Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired showed an increase in freezing, suggesting increased emotionality, our previous work suggests otherwise. Specifically, in Sevelinges et al. (2007), Infant Naïve/Adult Unpaired and Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired show similar increase in cue freezing, suggesting that the infant unpaired treatment did not influence the adult outcome. Furthermore, the increase in shock-induced CORT release and hippocampus 2-DG uptake in Infant Unpaired/Adult Unpaired group could reflect the expected context fear learning seen in unpaired animals; however, specific testing of context learning would be required (Phillips and LeDoux, 1994; Anagnostaras et al., 1999; Fanselow, 2000; Brasser and Spear, 2004). It should be noted that other measures of emotionality have found enhanced emotionality from unpredictable infant shock as indicated by the open field test (Levine et al., 1956; Bell and Debenberg, 1962; Henderson, 1965; Weiss, 1970), the light-dark emergence test (Tyler et al., 2007) and enhanced hippocampal activity (Alfarez et al., 2008; Mandyam et al., 2008).

Our data confirm previous research showing that, once acquired during the sensitive period, a learned odor approach response continues to be expressed as an approach, even in older pups (Sullivan et al., 2000). However, we extend this previous research to show that this occurs despite extensive continued odor-shock conditioning in postsensitive period pups old enough to learn the amygdala-dependent fear conditioning. These data suggest that once the infant attachment learning is acquired, the original memory is strengthened using the neonatal attachment learning circuit rather than “rewriting” the memory using the newly available amygdala fear circuit. Furthermore, these data complement previous data showing that infant odor learning produces a robust odor memory that is retained into adulthood to enhance sexual behavior (odor-stroking; Fillion and Blass, 1986 or odor-0.5 mA shock; Raineki et al., in prep). Our current work extends these data to show that the infant odor's value can be changed with additional odor-shock conditioning in adulthood, although both the learned fear and the involvement of the amygdala (Sevelinges et al., 2007) and hippocampus are attenuated compared to Naïve animals odor-shock conditioned for the first time. Therefore, the ability of odor-shock fear conditioning to activate the attachment learning circuit appears to be limited to early life, at least under the present experimental conditions.

Adult fear conditioning

Here we showed that animals with combined infant and adult paired odor-shock conditioning (Infant Paired/Adult Paired) exhibited attenuated amygdala-dependent fear conditioning that could be brought to normal levels with a systemic CORT injection during adult conditioning (Figures 6 and 9). This attenuation of fear is specific to the infant odor, which was present as context during the adult fear conditioning and replicates our previous work (Sevelinges et al., 2007, 2008, 2009). The present data extend these results and indicate that the attenuated shock-induced CORT release seen in infancy is maintained into adulthood and suggest that the attenuated CORT is critical for the attenuated adult fear (Figure 8). This relationship between CORT and learning found in the present study converges with previous work on adult learning and CORT (De Quervain et al., 2009; Rodrigues et al., 2009). However, since CORT has been shown to influence both acquisition, consolidation and reconsolidation of learned fear, our results could be due to modification of any or all of these processes.

Our results, showing increased adult hippocampal 2-DG uptake during adult conditioning (Infant Naïve/Adult Paired; Figure 9), confirm several studies demonstrating that the hippocampus is a fundamental structure supporting fear conditioning and contextual learning (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978; Fanselow, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Otto et al., 2000; Otto and Giardino, 2001; Rudy et al., 2002; Sanders et al., 2003). However, with combined infant and adult odor-shock conditioning (Infant Paired/Adult Paired), hippocampal 2-DG uptake was attenuated during adult fear conditioning. These data indicate that the hippocampus is processing information differently following paired infant odor-shock experience. Early life experiences have previously been shown to produce enduring effects on hippocampus neural function and plasticity and produce deficits in behavioral tasks generally considered to require an intact hippocampus (Caldji et al., 1998; Gutman and Nemeroff, 2002; Brunson et al., 2003; Fenoglio et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006; Kosten et al., 2006, 2007; Bagot et al., 2009).

Infant fear conditioning

We found that Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups maintain the attachment circuit inducing preference learning, and not the age typical amygdala-dependent fear learning (Infant Naïve/PN12 Paired) with continued odor-shock conditioning (Figures 3 and 5). These results complement previous results showing that sensitive period (≤PN9) infant rats learn an odor preference from odor-pain conditioning (Camp and Rudy, 1988; Sullivan et al., 2000; Roth and Sullivan, 2005; Moriceau et al., 2006) but by PN10, this conditioning supports amygdala-dependent fear learning (Sullivan et al., 2000; Moriceau et al., 2006). Our previous work showed that a shock-induced CORT increase is critical for pups' amygdala-dependent fear learning (Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004; Moriceau et al., 2006), which suggested that the blunted shock-induced CORT release of the Infant Paired/PN12 Paired might be responsible for the age atypical retention of the sensitive period attachment learning (Figure 4). For this reason, we overrode Infant Paired/PN12 Paired pups’ blunted shock-induced CORT release with a systemic CORT injection (3 mg/kg), which permitted the amygdala-dependent fear conditioning.

While the mechanism for the strong role of CORT in the infant amygdala plasticity has not been clarified, recent results from our lab suggests that CORT increases GABAergic function, which becomes more adult-like at the same age the amygdala-dependent fear conditioning emerges and can be prematurely induced with CORT (Thompson et al., 2008). The role of CORT modulation of GABA function in adult amygdala has previously been demonstrated (Duvarci and Pare, 2007; Lehner et al., 2008; Skorzewska et al., 2008). Furthermore, CORT increase triggers the release of endogenous CRH in central nucleus of the amygdala in both infant and adult rats, while early life stress only alters CRH in infancy (Plotsky and Meaney, 1993; Makino et al., 1994; Hatalski et al., 1998; Avishai-Eliner et al., 2001; Fenoglio et al., 2004; Korosi and Baram, 2008; Pitts et al., 2009). These data begin to describe unique neural functioning following early stress in infancy that results in unique learning constraints and capabilities that modify the infant and adult's response.

Infant odor-shock conditioning was not associated with activation of the hippocampus (CA1, CA3 and DG), even when CORT was injected (Figure 5). This is likely due to the late development of the hippocampus (Bayer and Altman, 1974; Bayer, 1980a,b,c; Ribak et al., 1985). Additionally, the hippocampus does not appear to be functional in fear conditioning until closer to weaning (Rudy, 1993, 1994; Brasser and Spear, 1998; Esmoris-Arranz et al., 2008; Raineki et al., 2009a), when the context or place of conditioning begins to be learned (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978; Fanselow, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Otto et al., 2000; Otto and Giardino, 2001; Debiec et al., 2002; Rudy et al., 2002; Sanders et al., 2003; Wiltgen et al., 2006).

Early life stress is generally characterized by a CORT increase in both infancy and adulthood. Indeed, maternal separation (depriving pup of the mother for prolonged time) leads to an elevation in baseline CORT, which is potentiated by presentation of a stressor in infancy and adulthood (Suchecki and Tufik, 1997; Dent et al., 2000; Rees et al., 2006). However, our early life stress paradigm using prolonged odor-shock conditioning is in sharp contrast with these studies because we showed a CORT decrease. Surprisingly, these results are similar to those of early life handling. Infant-handled rats show reduced fear as expressed by the increased exploratory activity and a decrease in both stress-induced CORT release and contextual fear learning (Bhatnagar and Meaney, 1995; Avishai-Eliner et al., 2001; Beane et al., 2002). While results have been interpreted as beneficial, other measures of handling, such as decreased reproduction and fearfulness to novel and aversive environments, suggest this may need to be reinterpretated (Nunez et al., 1996; Gomes et al., 1999, 2005; Meerlo et al., 1999; Padoin et al., 2001; Raineki et al., 2008).

Conclusion

Together, these results suggest that the effect of early life experiences differ during development and are specific to the age of assessment. In infancy, prolonged odor-shock conditioning, starting during the sensitive period, led to an age-atypical odor preference during the postsensitive period, instead of the age appropriate odor aversion. Continued conditioning was unable to switch the preference learning to aversion learning. Alternatively, the effects of the same prolonged infant odor-shock conditioning when assessed in adults indicates that additional fear conditioning was able to switch the preference learning to aversion learning, although at attenuated levels compared to naïve adult fear conditioning. However, consistency between infant and adults was found in the mediation of infant effects through learning and CORT suppression.

Importantly, here we show that an olfactory stimulus associated with infant trauma through classical conditioning gains control over fear learning and its underlying neural circuit. This suggests enduring effects of infant trauma are under CS control and are therefore more amenable to clinical intervention.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christopher K Cain for thoughtful suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript. The work was supported by NIH DC003906 and DC009910, NSF IOB0544406, Leon Levy Foundation, Hope for Depression Foundation to RMS and CAPES (Brazil) to CR.

References

- Akers K. G., Nakazawa M., Romeo R. D., Connor J. A., McEwen B. S., Tang A. C. (2006). Early life modulators and predictors of adult synaptic plasticity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 547–554 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarez D. N., Karst H., Velzing E. H., Joels M., Krugers H. J. (2008). Opposite effects of glucocorticoid receptor activation on hippocampal CA1 dendritic complexity in chronically stressed and handled animals. Hippocampus 18, 20–28 10.1002/hipo.20360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras S. G., Maren S., Fanselow M. S. (1999). Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: within-subjects examination. J. Neurosci. 19, 1106–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avishai-Eliner S., Eghbal-Ahmadi M., Tabachnik E., Brunson K. L., Baram T. Z. (2001). Down-regulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) precedes early-life experience-induced changes in hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA. Endocrinology 142, 89–97 10.1210/en.142.1.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagot R. C., van Hasselt F. N., Champagne D. L., Meaney M. J., Krugers H. J., Joels M. (2009). Maternal care determines rapid effects of stress mediators on synaptic plasticity in adult rat hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bayer S. A. (1980a). Development of the hippocampal region in the rat. I. Neurogenesis examined with 3H-thymidine autoradiography. J. Comp. Neurol. 190, 87–114 10.1002/cne.901900107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S. A. (1980b). Development of the hippocampal region in the rat. II. Morphogenesis during embryonic and early postnatal life. J. Comp. Neurol. 190, 115–134 10.1002/cne.901900108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S. A. (1980c). Quantitative 3H-thymidine radiographic analyses of neurogenesis in the rat amygdala. J. Comp. Neurol. 194, 845–875 10.1002/cne.901940409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S. A., Altman J. (1974). Hippocampal development in the rat: cytogenesis and morphogenesis examined with autoradiography and low-level X-irradiation. J. Comp. Neurol. 158, 55–79 10.1002/cne.901580105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beane M. L., Cole M. A., Spencer R. L., Rudy J. W. (2002). Neonatal handling enhances contextual fear conditioning and alters corticosterone stress responses in young rats. Horm. Behav. 41, 33–40 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. W., Debenberg V. H. (1962). The interrelationships of shcok and critical periods in infancy as they affect adult learning and activity. Anim. Behav. 11, 21–27 10.1016/0003-3472(63)90003-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S., Meaney M. J. (1995). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in chronic intermittently cold-stressed neonatally handled and non handled rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 7, 97–108 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1965). Attachment. New York, Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and Loss. New York, Basic Books; 4991343 [Google Scholar]

- Brake S. C. (1981). Suckling infant rats learn a preference for a novel olfactory stimulus paired with milk delivery. Science 211, 506–508 10.1126/science.7192882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasser S. M., Spear N. E. (1998). A sensory-enhanced context facilitates learning and multiple measures of unconditioned stimulus processing in the preweanling rat. Behav. Neurosci. 112, 126–140 10.1037/0735-7044.112.1.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasser S. M., Spear N. E. (2004). Contextual conditioning in infants, but not older animals, is facilitated by CS conditioning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 81, 46–59 10.1016/S1074-7427(03)00068-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J. D., Vermetten E., Schmahl C., Vaccarino V., Vythilingam M., Afzal N., Grillon C., Charney D. S. (2005). Positron emission tomographic imaging of neural correlates of a fear acquisition and extinction paradigm in women with childhood sexual-abuse-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 35, 791–806 10.1017/S0033291704003290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson K. L., Chen Y., Avishai-Eliner S., Baram T. Z. (2003). Stress and the developing hippocampus: a double-edged sword? Mol. Neurobiol. 27, 121–136 10.1385/MN:27:2:121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldji C., Tannenbaum B., Sharma S., Francis D., Plotsky P. M., Meaney M. J. (1998). Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5335–5340 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp L. L., Rudy J. W. (1988). Changes in the categorization of appetitive and aversive events during postnatal development of the rat. Dev. Psychobiol. 21, 25–42 10.1002/dev.420210103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne D. L., Bagot R. C., van Hasselt F., Ramakers G., Meaney M. J., de Kloet E. R., Joels M., Krugers H. (2008). Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. J. Neurosci. 28, 6037–6045 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0526-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F., Francia N., Berry A., Aloe L., Alleva E., Suomi S. J. (2009). Early life stress as a risk factor for mental health: role of neurotrophins from rodents to non-human primates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 573–585 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith R., Leon M. (1986). Enhanced neural response by adult rats to odors experienced early in life. Brain Res. 371, 400–403 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90384-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corodimas K. P., LeDoux J. E., Gold P. W., Schulkin J. (1994). Corticosterone potentiation of conditioned fear in rats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 746, 392–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Quervain D. J., Aerni A., Schelling G., Roozendaal B. (2009). Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory in health and disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 30, 358–370 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J., LeDoux J. E. (2006). Noradrenergic signaling in the amygdala contributes to the reconsolidation of fear memory: treatment implications for PTSD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1071, 521–524 10.1196/annals.1364.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J., LeDoux J. E., Nader K. (2002). Cellular and systems reconsolidation in the hippocampus. Neuron 36, 527–538 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01001-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent G. W., Smith M. A., Levine S. (2000). Rapid induction of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene transcription in the paraventricular nucleus of the developing rat. Endocrinology 141, 1593–1598 10.1210/en.141.5.1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent G. W., Smith M. A., Levine S. (2001). Stress-induced alterations in locus coeruleus gene expression during ontogeny. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 127, 23–30 10.1016/S0165-3806(01)00108-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W. C. (2003). Neuroimaging abnormalities in the amygdala in mood disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 985, 420–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S., Pare D. (2007). Glucocorticoids enhance the excitability of principal basolateral amygdala neurons. J. Neurosci. 27, 4482–4491 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0680-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmoris-Arranz F. J., Mendez C., Spear N. E. (2008). Contextual fear conditioning differs for infant, adolescent, and adult rats. Behav. Processes. 78, 340–350 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow M. S. (2000). Contextual fear, gestalt memories, and the hippocampus. Behav. Brain Res. 110, 73–81 10.1016/S0166-4328(99)00186-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow M. S., Gale G. D. (2003). The amygdala, fear, and memory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 985, 125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoglio K. A., Brunson K. L., Avishai-Eliner S., Chen Y., Baram T. Z. (2004). Region-specific onset of handling-induced changes in corticotropin-releasing factor and glucocorticoid receptor expression. Endocrinology 145, 2702–2706 10.1210/en.2004-0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoglio K. A., Brunson K. L., Baram T. Z. (2006). Hippocampal neuroplasticity induced by early-life stress: functional and molecular aspects. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 27, 180–192 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion T. J., Blass E. M. (1986). Infantile experience with suckling odors determines adult sexual behavior in male rats. Science 231, 729–731 10.1126/science.3945807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect and the brain – a review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 41, 97–116 10.1017/S0021963099004990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C. M., Frantz P. J., Sanvitto G. L., Anselmo-Franci J. A., Lucion A. B. (1999). Neonatal handling induces anovulatory estrous cycles in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 32, 1239–1242 10.1590/S0100-879X1999001000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C. M., Raineki C., Ramos de Paula P., Severino G. S., Helena C. V., Anselmo-Franci J. A., Franci C. R., Sanvitto G. L., Lucion A. B. (2005). Neonatal handling and reproductive function in female rats. J. Endocrinol. 184, 435–445 10.1677/joe.1.05907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L. S., Gilman A. G. (1985). The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York, NY, Macmillan Publishing Company [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A. W., Churchill J. D., McKinney B. C., Kodish I. M., Otte S. L., Greenough W. T. (2003). Experience effects on brain development: possible contributions to psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 44, 33–63 10.1111/1469-7610.t01-1-00102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M., Quevedo K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 58, 145–173 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman D. A., Nemeroff C. B. (2002). Neurobiology of early life stress: rodent studies. Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 7, 89–95 10.1053/scnp.2002.31781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock E. A. D., Levitt P. (2006). The discipline of neurobehavioral development: the emerging interface of processes that build circuits and skills. Hum. Dev. 49, 294–309 10.1159/000095581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow H. F., Harlow M. K. (1965). The affectional systems. In Behavior of Nonhuman Primates, Schrier A., Harlow H. F., Stollnitz F., eds (New York, Academic Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Haroutunian V., Campbell B. A. (1979). Emergence of interoceptive and exteroceptive control of behavior in rats. Science 205, 927–929 10.1126/science.472715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatalski C. G., Guirguis C., Baram T. Z. (1998). Corticotropin releasing factor mRNA expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and the central nucleus of the amygdala is modulated by repeated acute stress in the immature rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 10, 663–669 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00246.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer M. E., Kempe R. S., Krugman R. D. (1997). The Battered Child. Chicago, University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Henderson N. D. (1965). Acquisition and retention of conditioned fear during different stages in the development of mice. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 59, 439–442 10.1037/h0022039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess E. H. (1962). Ethology: an approach to the complete analysis of behavior. In New Directions in Psychology, Brown R., Galanter E., Hess E. H., Mendler G., eds (New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hinde R. A. (1991). John Bowlby. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 32, 215–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde R. A., Spencer-Booth Y. (1967). The behaviour of socially living rhesus monkeys in their first two and a half years. Anim. Behav. 15, 169–196 10.1016/S0003-3472(67)80029-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui G. K., Figueroa I. R., Poytress B. S., Roozendaal B., McGaugh J. L., Weinberger N. M. (2004). Memory enhancement of classical fear conditioning by post-training injections of corticosterone in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 81, 67–74 10.1016/j.nlm.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson I. B., Hall W. G. (1979). Appetitive learning in 1-day-old rat pups. Science 205, 419–421 10.1126/science.451612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl K. A., Smith A. M., Hare R. D., Mendrek A., Forster B. B., Brink J., Liddle P. F. (2001). Limbic abnormalities in affective processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biol. Psychiatry 50, 677–684 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01222-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. J., Song E. Y., Kosten T. A. (2006). Stress effects in the hippocampus: synaptic plasticity and memory. Stress 9, 1–11 10.1080/10253890600678004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korosi A., Baram T. Z. (2008). The central corticotropin releasing factor system during development and adulthood. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 583, 204–214 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten T. A., Karanian D. A., Yeh J., Haile C. N., Kim J. J., Kehoe P., Bahr B. A. (2007). Memory impairments and hippocampal modifications in adult rats with neonatal isolation stress experience. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 88, 167–176 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten T. A., Lee H. J., Kim J. J. (2006). Early life stress impairs fear conditioning in adult male and female rats. Brain Res. 1087, 142–150 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet D., Greer C. A., Kauer J. S., Shepherd G. M. (1982). Mapping of odor-related neuronal activity in the olfactory bulb by high-resolution 2-deoxyglucose autoradiography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 670–674 10.1073/pnas.79.2.670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 155–184 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner M., Taracha E., Skorzewska A., Turzynska D., Sobolewska A., Maciejak P., Szyndler J., Hamed A., Bidzinski A., Wislowska-Stanek A., Plaznik A. (2008). Expression of c-Fos and CRF in the brains of rats differing in the strength of a fear response. Behav. Brain Res. 188, 154–167 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. (2001). Primary social relationships influence the development of the hypothalamic – pituitary – adrenal axis in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 73, 255–260 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00496-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S., Chevalier J. A., Korchin S. J. (1956). The effects of early shock and handling on later avoidance learning. J. Pers. 24, 475–493 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1956.tb01283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D., Tomaszycki M., Carroll K. A. (1999). Consistency and change in the behavior of rhesus macaque abusive mothers with successive infants. Dev. Psychobiol. 34, 29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Gold P. W., Schulkin J. (1994). Corticosterone effects on corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA in the central nucleus of the amygdala and the parvocellular region of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res. 640, 105–112 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91862-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandyam C. D., Crawford E. F., Eisch A. J., Rivier C. L., Richardson H. N. (2008). Stress experienced in utero reduces sexual dichotomies in neurogenesis, microenvironment, and cell death in the adult rat hippocampus. Dev. Neurobiol. 68, 575–589 10.1002/dneu.20600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. (2003). The amygdala, synaptic plasticity, and fear memory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 985, 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerlo P., Horvath K. M., Nagy G. M., Bohus B., Koolhaas J. M. (1999). The influence of postnatal handling on adult neuroendocrine and behavioural stress reactivity. J. Neuroendocrinol. 11, 925–933 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriceau S., Sullivan R. M. (2004). Corticosterone influences on Mammalian neonatal sensitive-period learning. Behav. Neurosci. 118, 274–281 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriceau S., Sullivan R. M. (2006). Maternal presence serves as a switch between learning fear and attraction in infancy. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1004–1006 10.1038/nn1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriceau S., Wilson D. A., Levine S., Sullivan R. M. (2006). Dual circuitry for odor-shock conditioning during infancy: corticosterone switches between fear and attraction via amygdala. J. Neurosci. 26, 6737–6748 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0499-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. F., Ferre P., Escorihuela R. M., Tobena A., Fernandez-Teruel A. (1996). Effects of postnatal handling of rats on emotional, HPA-axis, and prolactin reactivity to novelty and conflict. Physiol. Behav. 60, 1355–1359 10.1016/S0031-9384(96)00225-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J., Nadel L. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. New York, Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Otto T., Cousens G., Herzog C. (2000). Behavioral and neuropsychological foundations of olfactory fear conditioning. Behav. Brain Res. 110, 119–128 10.1016/S0166-4328(99)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto T., Giardino N. D. (2001). Pavlovian conditioning of emotional responses to olfactory and contextual stimuli: a potential model for the development and expression of chemical intolerance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 933, 291–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoin M. J., Cadore L. P., Gomes C. M., Barros H. M., Lucion A. B. (2001). Long-lasting effects of neonatal stimulation on the behavior of rats. Behav. Neurosci. 115, 1332–1340 10.1037/0735-7044.115.6.1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. E., Williams C. L., Blass E. M. (1982). Activation and odor conditioning of suckling behavior in 3-day-old albino rats. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 8, 329–341 10.1037/0097-7403.8.4.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R. G., LeDoux J. E. (1994). Lesions of the dorsal hippocampal formation interfere with background but not foreground contextual fear conditioning. Learn. Mem. 1, 34–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts M. W., Todorovic C., Blank T., Takahashi L. K. (2009). The central nucleus of the amygdala and corticotropin-releasing factor: insights into contextual fear memory. J. Neurosci. 29, 7379–7388 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0740-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky P. M., Meaney M. J. (1993). Early, postnatal experience alters hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA, median eminence CRF content and stress-induced release in adult rats. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 18, 195–200 10.1016/0169-328X(93)90189-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky P. M., Thrivikraman K. V., Nemeroff C. B., Caldji C., Sharma S., Meaney M. J. (2005). Long-term consequences of neonatal rearing on central corticotropin-releasing factor systems in adult male rat offspring. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 2192–2204 10.1038/sj.npp.1300769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh C. R., Tremblay D., Fleshner M., Rudy J. W. (1997). A selective role for corticosterone in contextual-fear conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 111, 503–511 10.1037/0735-7044.111.3.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C., Holman P., Bugg M., Beasley A., Sullivan R. M. (2009a). Maternal modulation of the functional emergence of the hippocampus in context fear learning in infant rats. Abstract for Association for Chemosensory Sciences [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raineki C., Shionoya K., Sander K., Sullivan R. M. (2009b). Ontogeny of odor-LiCl vs. odor-shock learning: similar behaviors but divergent amygdala functional emergence. Learn. Mem. 16, 114–121 10.1101/lm.977909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C., Szawka R. E., Gomes C. M., Lucion M. K., Barp J., Bello-Klein A., Franci C. R., Anselmo-Franci J. A., Sanvitto G. L., Lucion A. B. (2008). Effects of neonatal handling on central noradrenergic and nitric oxidergic systems and reproductive parameters in female rats. Neuroendocrinology 87, 151–159 10.1159/000112230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattiner L. M., Davis M., Ressler K. J. (2005). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in amygdala-dependent learning. Neuroscientist 11, 323–333 10.1177/1073858404272255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S. L., Steiner M., Fleming A. S. (2006). Early deprivation, but not maternal separation, attenuates rise in corticosterone levels after exposure to a novel environment in both juvenile and adult female rats. Behav. Brain Res. 175, 383–391 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribak C. E., Seress L., Amaral D. G. (1985). The development, ultrastructure and synaptic connections of the mossy cells of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurocytol. 14, 835–857 10.1007/BF01170832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues S. M., Ledoux J. E., Sapolsky R. M. (2009). The influence of stress hormones on fear circuitry. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 289–313 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B. (2002). Stress and memory: opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 78, 578–595 10.1006/nlme.2002.4080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B., Hui G. K., Hui I. R., Berlau D. J., McGaugh J. L., Weinberger N. M. (2006). Basolateral amygdala noradrenergic activity mediates corticosterone-induced enhancement of auditory fear conditioning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 86, 249–255 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T. L., Sullivan R. M. (2005). Memory of early maltreatment: neonatal behavioral and neural correlates of maternal maltreatment within the context of classical conditioning. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 823–831 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy J. W. (1993). Contextual conditioning and auditory cue conditioning dissociate during development. Behav. Neurosci. 107, 887–891 10.1037/0735-7044.107.5.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy J. W. (1994). Ontogeny of context-specific latent inhibition of conditioned fear: implications for configural associations theory and hippocampal formation development. Dev. Psychobiol. 27, 367–379 10.1002/dev.420270605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy J. W., Barrientos R. M., O'Reilly R. C. (2002). Hippocampal formation supports conditioning to memory of a context. Behav. Neurosci. 116, 530–538 10.1037/0735-7044.116.4.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzen E. A. (1970). Imprinting and environmental learning. In Development and Evolution of Behavior, Aronson L. R., Tobach E., Lehrman D. S., Rosensbaltt J., eds (San Francisco, W H Freeman; ). [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M. M., Ladd C. O., Plotsky P. M. (2001). Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models. Dev. Psychopathol. 13, 419–449 10.1017/S0954579401003029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M. J., Wiltgen B. J., Fanselow M. S. (2003). The place of the hippocampus in fear conditioning. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 463, 217–223 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01283-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandi C., Venero C., Guaza C. (1995). Decreased spontaneous motor activity and startle response in nitric oxide synthase inhibitor-treated rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 277, 89–97 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00068-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettino L. F., Otto T. (2001). Patterns of Fos expression in the amygdala and ventral perirhinal cortex induced by training in an olfactory fear conditioning paradigm. Behav. Neurosci. 115, 1257–1272 10.1037/0735-7044.115.6.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y., Gervais R., Messaoudi B., Granjon L., Mouly A. M. (2004). Olfactory fear conditioning induces field potential potentiation in rat olfactory cortex and amygdala. Learn. Mem. 11, 761–769 10.1101/lm.83604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y., Moriceau S., Holman P., Miner C., Muzny K., Gervais R., Mouly A. M., Sullivan R. M. (2007). Enduring effects of infant memories: infant odor-shock conditioning attenuates amygdala activity and adult fear conditioning. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 1070–1079 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y., Mouly A. M., Levy F., Ferreira G. (2009). Long-term effects of infant learning on adult conditioned odor aversion are determined by the last preweaning experience. Dev. Psychobiol. 51, 389–398 10.1002/dev.20378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y., Sullivan R. M., Messaoudi B., Mouly A. M. (2008). Neonatal odor-shock conditioning alters the neural network involved in odor fear learning at adulthood. Learn. Mem. 15, 649–656 10.1101/lm.998508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline Y. I., Barch D. M., Donnelly J. M., Ollinger J. M., Snyder A. Z., Mintun M. A. (2001). Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol. Psychiatry 50, 651–658 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01263-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson T., Doyere V., Cain C. K., LeDoux J. E. (2007). Long-term potentiation in the amygdala: a cellular mechanism of fear learning and memory. Neuropharmacology 52, 215–227 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorzewska A., Bidzinski A., Hamed A., Lehner M., Turzynska D., Sobolewska A., Maciejak P., Szyndler J., Wislowska-Stanek A., Plaznik A. (2008). The influence of CRF and alpha-helical CRF(9-41) on rat fear responses, c-Fos and CRF expression, and concentration of amino acids in brain structures. Horm. Behav. 54, 602–612 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley W. E. (1962). Differential human handling as reinforcing events and as treatments influencing later social behavior in basenji puppies. Psychol. Rep. 10, 775–788 [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki D., Tufik S. (1997). Long-term effects of maternal deprivation on the corticosterone response to stress in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 273, R1332–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Brake S. C., Hofer M. A., Williams C. L. (1986a). Huddling and independent feeding of neonatal rats can be facilitated by a conditioned change in behavioral state. Dev. Psychobiol. 19, 625–635 10.1002/dev.420190613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Hofer M. A., Brake S. C. (1986b). Olfactory-guided orientation in neonatal rats is enhanced by a conditioned change in behavioral state. Dev. Psychobiol. 19, 615–623 10.1002/dev.420190612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Landers M., Yeaman B., Wilson D. A. (2000). Good memories of bad events in infancy. Nature 407, 38–39 10.1038/35024156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Leon M. (1986). Early olfactory learning induces an enhanced olfactory bulb response in young rats. Brain Res. 392, 278–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Wilson D. A., Leon M. (1989). Norepinephrine and learning-induced plasticity in infant rat olfactory system. J. Neurosci. 9, 3998–4006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Wilson D. A., Wong R., Correa A., Leon M. (1990). Modified behavioral and olfactory bulb responses to maternal odors in preweanling rats. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 53, 243–247 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90013-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi S. J. (2006). Risk, resilience, and gene × environment interactions in rhesus monkeys. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1094, 52–62 10.1196/annals.1376.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi L. K. (1994). Organizing action of corticosterone on the development of behavioral inhibition in the preweanling rat. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 81, 121–127 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher M. H., Andersen S. L., Polcari A., Anderson C. M., Navalta C. P., Kim D. M. (2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 27, 33–44 10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. L., Erickson K., Schulkin J., Rosen J. B. (2004). Corticosterone facilitates retention of contextually conditioned fear and increases CRH mRNA expression in the amygdala. Behav. Brain Res. 149, 209–215 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00216-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]