SUMMARY

Legionella pneumophila is an intracellular pathogen of freshwater amoeba and of alveolar macrophages in human hosts. After phagocytosis, L. pneumophila establishes a unique intracellular vacuolar niche that avoids entry into the lysosomal network. Critical for L. pneumophila intracellular growth is the Dot/Icm type IVB translocation system. While over eighty substrates of the Dot/Icm apparatus have been identified, individual substrates are often genetically redundant, complicating their analysis. Deletion of critical Dot/Icm translocation system components causes a variety of defects during intracellular growth. Many of these effects on the host cell likely result from the actions of one or more Dot/Icm translocated substrates. Loss of single substrates never generates the profound effects observed in strains lacking translocation system components.

INTRODUCTION

Legionella pneumophila is a Gram-negative facultative intravacuolar bacterial pathogen [1]. The primary natural reservoir of L. pneumophila is likely freshwater amoeba, where the bacteria replicate intracellularly in a specialized vacuole that avoids interaction with the lysosomal network, at least during the early stages of replication. In human hosts, the inhalation of either aerosolized bacteria or amoebae harboring L. pneumophila leads to infection of alveolar macrophages, which can result in an atypical pneumonia with high mortality, especially in immunocompromised patients. L. pneumophila exhibits a broad host range, and the replication of the bacteria in alveolar macrophages is remarkably similar to its replication in its natural amoebal hosts. Whether in amoeba or macrophages, a large cohort of bacterial effectors delivered to the host cytosol by the Dot/Icm type IVB translocation apparatus modulates host processes [2,3]. The translocation machinery comprises a set of 26 proteins whose individual functions remain largely unknown [4].

Over eighty effectors have been identified through a variety of genetic, biochemical, and cell biological approaches, yet the function of the majority of these substrates remains undefined [5]. One factor complicating the analysis of these substrates is that individually the vast majority of them are genetically dispensable for growth of bacteria within cultured eukaryotic cells, indicating a high degree of genetic redundancy.

IDENTIFICATION OF DOT/ICM TRANSLOCATED SUBSTRATES

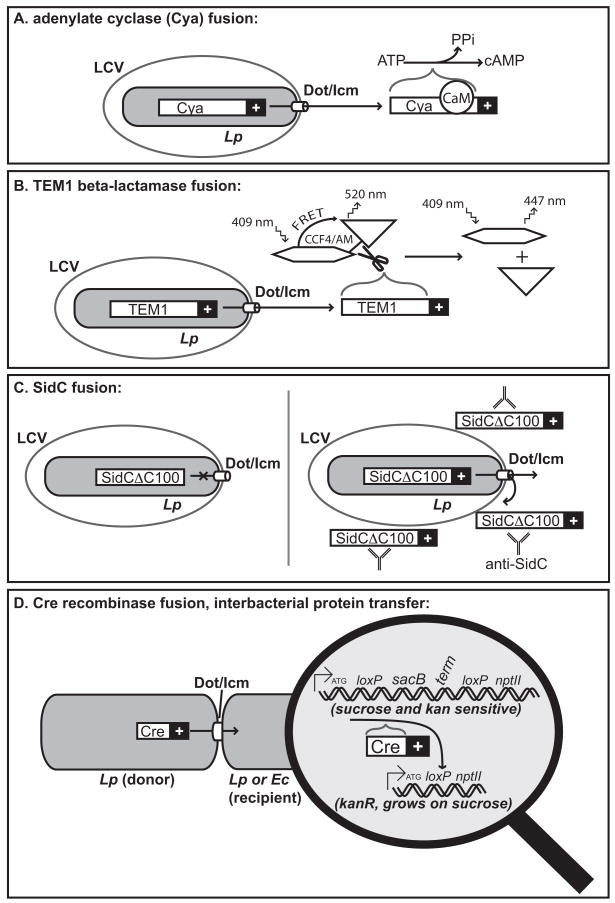

Over the last several years, putative substrates have been identified through directed translocation assays [6,7], heterologous expression systems [8,9], and/or homology to known eukaryotic motifs [10–13]. Notably, the translocated substrates of the Dot/Icm system do not generally form pathogenicity islands, nor do they co-cluster in the genome with genes encoding the translocation machinery [10,14]. A number of functional assays for translocation by the Dot/Icm system have been developed and adapted from other systems (Figure 1) [7,11,15,16]. The signal sequences responsible for Dot/Icm translocation are largely unknown, but a growing body of evidence suggests that they largely reside at the C-terminus of translocated substrates [6,7,15]. With this in mind, fusions of candidate substrates to reporter sequences are typically made with the candidate sequence placed C-terminus to the particular reporter domain. Direct observation of translocation by immunofluorescence or subcellular fractionation has also been observed in cases where antibodies have been generated to specific candidate substrates [7,13]. In cases where the interpretation of these results may be complicated by low levels of endogenous expression, over-expression of a substrate may be necessary [17].

Figure 1. Measuring Dot/Icm-dependent translocation.

(A) The fusion of a positive translocation signal (“+”) to the C-terminus of adenylate cyclase (Cya) results in translocation of the fusion protein into the host cytosol. Cya activity depends on the host protein calmodulin (CaM), thus the level of cAMP in infected cells is directly proportional to translocation efficiency. As is the case for (B–D) as well, translocation is not observed in Dot/Icm deficient strains or with the reporter sequence alone. (B) In the TEM1 beta-lactamase fusion assay, a reporter substrate (CCF4/AM) is loaded into host cells. Translocation of beta-lactamase fusions results in a loss of FRET due to cleavage between the FRET donor and FRET acceptor of the substrate molecule. (C) An N-terminal fragment of the known Dot/Icm substrate, SidC, is unable to translocate on its own. Translocation can be restored by the fusion of other translocated substrates (or their C-termini) to SidCΔC100. SidC remains associated with the LCV after translocation, facilitating direct immunofluorescent detection of translocation using antibodies generated to SidC. (D) The Dot/Icm translocation machinery supports interbacterial transfer of protein substrates. A donor Legionella strain contains Cre recombinase fused to a candidate translocation signal. A recipient Legionella (or E. coli) strain contains a loxP-flanked reporter site, such that Cre-mediated recombination results in the loss of a counter-selectable marker (sacB) and the generation of a functional loxP-neomycin phosphotransferase (nptII) translational fusion, thereby conferring kanamycin resistance.

These hunts indicate that the genome of L. pneumophila encodes a strikingly large number of Dot/Icm substrates that are translocated into the host during infection. Well over 80 substrates have been identified so far, and many of the candidates identified in these screens are now being systematically studied in order to define their role during replication within host cells.

DOT/ICM TRANSLOCATION COLLECTIVELY HAS BROAD EFFECTS ON THE HOST CELL

While the vast majority of individual translocated substrates are genetically dispensable for the intracellular replication of L. pneumophila, critical components of the translocation apparatus are themselves required for both intracellular growth and disease within animals. These translocation-dependent phenotypes include avoiding association with markers of the endosome-lysosome fusion shortly after uptake into host cells, the recruitment of components of the early secretory system to the Legionella containing vacuole (LCV), as well as modulation of host signal transduction cascades (Table 1). Many of these Dot/Icm-dependent effects on the host cell during Legionella infection likely result from the actions of one or more translocated bacterial effectors. Known effectors can be assigned to many of these Dot/Icm dependent phenotypes (Table 2), but the proteins necessary to promote many more characterized phenotypes remain to be identified.

Table 1.

Alterations in host cells in response to Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm System

| Dot/Icm-dependent process | Reference(s) |

|---|---|

| Vacuolar remodeling | |

| Endosome-lysosome fusion avoidance | [46] |

| ER recruitment | [24] |

| Mitochondrial recruitment | [47] |

| Polyubiquitin recruitment | [27,48] |

| Host cell death induction | |

| Dose-dependent cytotoxicity | [21,34] |

| Red blood cell lysis | [34,37] |

| Type I interferon response | [49] |

| Caspase activation | [50–52] |

| Inhibition of protein synthesis | [38,39] |

| Host cell death inhibition | |

| NF-kappa-B activation | [40,41] |

| Bcl2 inhibition | [42] |

| Other | |

| Upregulation of phagocytosis | [53] |

| Bacterial conjugation | [2,3,7] |

| Inhibition of DALIS formation | [48] |

Table 2.

Properties of Dot/Icm translocated substrates.

| Name | Activity and/or Function | Host interactions | Strains* | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuolar remodeling: | ||||

| LegA8/AnkX/AnkN | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [12,20,23] |

| LegC2/YlfB | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [9,11,12] |

| LegC7/YlfA | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [9,11,12] |

| LepB | Rab1 GAP (also non-lytic release from protozoa) | Rab1 | Ph, Pa, L, C | [31,37] |

| LidA | Rab1 GEF; Rab1 tethering | GDI-free Rab1 | Ph, Pa, L, C | [21,29] |

| RalF | Arf1 GEF; Arf1 recruitment to the LCV | Arf1 | Ph, Pa, L, C | [13] |

| SetA | glucosyltransferase; vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [32] |

| SidC | ER-recruitment | PI(4)P | Ph, Pa, L, C | [28,36] |

| SidJ | ER-recruitment | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [33] |

| SidM/DrrA | Rab1 GEF/GDF; Rab1 recruitment to the LCV | Rab1 | Ph, L | [22,29–31] |

| VipA | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [8] |

| VipD | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa | [8] |

| VipE | vesicle trafficking | unknown | Ph, Pa, L | [8] |

| Stimulation of host cell death: | ||||

| LegU2/LubX | U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase; modulation of cell cycle? | Clk1 | Ph, Pa | [6] |

| Lgt1 | glucosyltransferase; inhibition of host protein synthesis | eEF1A | Ph, Pa, L, C | [38,39] |

| LegC8/Lgt2 | glucosyltransferase; inhibition of host protein synthesis | eEF1A | Ph, C | [12,39] |

| LegC5/Lgt3 | glucosyltransferase; inhibition of hosprotein synthesis | eEF1A | Ph, Pa, L, C | [12,39] |

| Host cell survival: | ||||

| SdhA | anti-apoptosis | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [17] |

| SidF | anti-apoptosis | Bcl2 | Ph, Pa, L, C | [42] |

| Other: | ||||

| LepA | non-lytic release from protozoa | unknown | Ph, Pa, L, C | [37] |

L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila str. Philadelphia 1 (Ph), L. pneumophila str. Paris (Pa), L. pneumophila str. Lens (L), and L. pneumophila str. Corby (C).

LYSOSOMAL AVOIDANCE

Shortly after uptake into the host cell, a Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) is established that is the site of intracellular replication. While phagosomes containing avirulent bacteria fuse with acidified LAMP1-positive lysosomal compartments, strains with a functional Dot/Icm complex generally avoid endosome-lysosome fusion shortly after uptake. (During late stages of infection, the extent of this avoidance may vary depending on cell type [18,19]). It has been proposed that a subset of effectors may function to directly block lysosomal fusion [20], however, lysosomal avoidance may also be an indirect result of the modulation of other host trafficking events. Strains carrying mutations in the translocated substrate, LidA, reside in LCVs that are more likely to co-localize with lysosomal markers such as LAMP1 [21]. While this phenotype might suggest a direct role for LidA in interfering with lysosomal avoidance, careful molecular characterization of the protein suggests that this may be an indirect result of subtle changes in Rab1 trafficking to the LCV [22]. A recently described ankyrin repeat containing protein, LegA8/AnkX/AnkN [12,20,23] may prevent lysosome fusion with the LCV by disrupting microtubule-dependent vesicle transport [20], although its effects on lysosomal fusion may also be indirect.

HOST PROTEIN RECRUITMENT

A number of components of host secretory traffic are recruited to the LCV in a Dot/Icm-dependent manner. As soon as 15 minutes after uptake, ER-derived host vesicles accumulate around the LCV. These are accompanied by host factors that modulate ER to Golgi traffic: calnexin, phosphatidylinositol(4) phosphate (PI(4)P), Sec22b, and the small GTPases Arf1 and Rab1 [13,24–28]. As infection progresses, ribosomes and mitochondria are also recruited to the LCV and recruited vesicles fuse to complete the establishment of a replicative vacuole with striking similarities to rough ER.

In order to modulate ER to Golgi trafficking in a normal eukaryotic cell, the small GTPases Arf1 and Rab1 are regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote the exchange of GDP for the activating nucleotide GTP. The discovery of the first Dot/Icm translocated effector, RalF, was based on a search for L. pneumophila genes with homology to eukaryotic Arf GEFs [13]. RalF has homology to the eukaryotic Sec7 Arf-GEF, supports nucleotide exchange in vitro, and is necessary for the recruitment of Arf1 to the LCV during infection.

Another L. pneumophila translocated effector, SidM/DrrA, has been identified as a GEF for Rab1 [29,30]. L. pneumophila strains deleted for SidM/DrrA do not display an intracellular growth defect, but fail to recruit Rab1 to the LCV. In addition to exhibiting GEF activity towards Rab1 in vitro, SidM is also involved in earlier stages of Rab1 activation, by first catalyzing the liberation of Rab1 from a protein that blocks nucleotide exchange, GDP-dissociation inhibitor (GDI) [22,31]. Not only is SidM one of the first GDI-displacement factors to be described in any system, the combination of GEF and GDF activity in the same enzyme is an unexpected result that may provide general insight into host GTPase activation and vesicle trafficking. Adding to the intricacy of Rab1 recruitment by L. pneumophila, the translocated effector LidA is thought to tether GDI-free Rab1 to the LCV membrane and can allow recruitment of Rab1 to vacuoles harboring sidM− mutants in host cells expressing a mutant form of Rab1 that does not bind GDI [22].

Other translocated substrates that may manipulate host membrane trafficking pathways have been identified using inducible protein expression systems in yeast. L. pneumophila proteins that interact with host cell components, when ectopically expressed in S. cerevisiae, can cause the misregulation of host proteins and often cause yeast growth defects. Initial screens analyzed the phenotypes of S. cerevisiae strains expressing L. pneumophila proteins from shotgun gene banks. These screens identified a number of translocated substrates whose expression causes growth and/or secretory defects, including VipA, VipD, VipE, LegC2/YlfB, LegC3, and LegC7/YlfA [8,9,11]. Notably, the previously identified effectors LidA, RalF, and SidM also cause similar phenotypes when heterologously expressed in yeast [32].

A recent directed screen of putative L. pneumophila effectors identified a number of additional candidate substrates whose heterologous expression in yeast lead to growth and/or secretory defects [32]. One of these translocated substrates with a probable role in modulating host protein trafficking is SetA, a glucosyltransferase with an unidentified eukaryotic substrate. Interestingly, SetA may be polyubiquitinated in the host cytosol, though the effects of this posttranslational modification on SetA activity are not yet understood. With a large group of candidate substrates identified through translocation assays, this study likely represents the first of many that will use directed libraries Legionella proteins to examine putative effector function in various systems.

Another translocated substrate with a potential role in modulating host vesicle trafficking is SidJ [33]. Shortly after uptake, the kinetics of ER marker recruitment are reduced in sidJ− strains, suggesting that SidJ may be involved in the early stages of vesicle recruitment to the LCV. It is clear, however, that there are several other bacterial proteins involved in vesicle recruitment that have yet to be identified. In addition, other Dot/Icm-dependent recruitment events, such as the accumulation of polyubiquitinated substrates surrounding the LCV, have not yet been explained by the action of specific effectors.

HOST CELL DEATH AND SURVIVAL

In addition to manipulation of vesicle traffic, a number of other Dot/Icm-dependent alterations in host cell physiology have been observed. High multiplicities of infection (MOI) with wild-type L. pneumophila lead to dose-dependent cytotoxic effects in primary bone marrow macrophages, yet translocation-deficient strains are largely not cytotoxic [21,34–36]. Similarly, L. pneumophila is able to lyse red blood cells in a Dot/Icm-dependent manner, a phenotype that has been used as a readout for proper assembly of the translocation system[34,37]. These cytotoxic effects may be the result of the pore-forming ability of the type IVB translocation machinery, however, there is evidence to suggest a positive relationship between the active translocation of substrates and host cytotoxicity [37]. The intriguing possibility remains that individual effectors may contribute to the activation of host cell death pathways.

Translocated substrates that likely contribute to host cell cytotoxicity during infection include Lgt1, LegC8/Lgt2, and LegC5/Lgt3, glucosyltransferases of the highly abundant eukaryotic elongation factor eEF1A [38,39]. Glucosylation of eEF1A during infection inhibits host protein synthesis. The effects of Lgt1 translocation appear to be cytotoxic to cells and one hypothesis is that this cytotoxicity helps support the ability of bacteria to lyse out of the host cell at the end of their intracellular replicative phase. Alternatively, inhibiting host protein synthesis likely leads to a multitude of pleiotropic effects and this cytotoxicity may be a tolerated side effect of some other pro-bacterial consequence of this inhibition.

In contrast to the cytotoxicity observed during high MOI infection, low-dose infection by L. pneumophila induces anti-apoptotic host pathways in a Dot/Icm-dependent fashion. For instance, the host anti-apoptotic NF-kappa-B (NFκB) pathway is highly induced upon L. pneumophila infection in a Dot/Icm dependent manner [40,41]. One explanation for this is to presume the existence of one or more translocated effectors that function to attenuate host cell death by activating NFκB.

At least two L. pneumophila translocated substrates are proposed to have anti-death activities during infection. The translocated substrate, SdhA, interferes with caspase-dependent death during infection through an unknown mechanism [17]. Similarly, SidF may also serve to reduce apoptotic signaling, by inhibiting the pro-apoptotic Bcl2 family members BNIP and Bcl-Rambo [42]. Neither SidF nor SdhA activate NFκB signaling in host cells, suggesting that additional effectors serve to protect the host from cell death.

DOT/ICM-DEPENDENT ASSOCIATION WITH THE HOST UBIQUITINATION SYSTEM

Another translocated substrate, identified through its homology to a known eukaryotic motif and in directed screens for Dot/Icm translocated proteins, is LegU2/LubX [6,12]. LegU2 contains two U-box domains, a eukaryotic motif normally associated with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. LegU2 functions to ubiquitinate the host cell cycle protein Clk1, but the resulting effects on virulence are unknown. Strains lacking LegU2 do not display an intracellular growth defect, suggesting that other translocated substrates may target Clk1 for degradation in support of L. pneumophila replication. Counter-intuitively, chemical inhibition of Clk1 activity interferes with the ability of wild-type Legionella to replicate intracellularly, suggesting a more nuanced role for bacterial LegU2 and host Clk1 during infection. Like the effects of Lgt1 on eEF1A, the consequences of LegU2-mediated ubiquitination of Clk1 may modulate a multitude of host processes.

At least two substrates containing eukaryotic F-box domains typically associated with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity have been identified in L. pneumophila [12], raising the intriguing possibility that these L. pneumophila proteins may also hijack the host ubiquitin system in support of intracellular replication. Like other putative substrates currently being examined, the identification of their host substrates promises to place the function of these putative substrates into one of the broad categories above.

CONCLUSIONS

As of the writing of this review, over eighty translocated substrates have been identified, however the number of unidentified Dot/Icm substrates may be much higher. With so many putative translocated substrates in the L. pneumophila genome, much work remains to confirm the translocation potential of individual bacterial substrates and to examine their role in virulence. The revisiting of Dot/Icm-dependent phenotypes can help inform ongoing characterization of these Dot/Icm substrates. While outside the scope of this review, L. pneumophila also produces both a type II and a type IVA secretion system, both of which likely contribute to virulence under specific conditions [43,44].

With respect to Dot/Icm translocation as a whole, many broader questions remain. For instance, the extent to which the intracellular environment and host components regulate the scope and efficiency of Dot/Icm translocation is unknown. Also, while much focus has been given to the early stages of Dot/Icm dependent remodeling of the intracellular environment, relatively little is known about the prevalence and function of translocation at later points in the intracellular replication cycle. Some of the substrates that have been identified as having impact on the host cell immediately after uptake of the bacteria, such as SdhA, also may have important roles to play late in infection when the cumulative effect of other factors would otherwise lead to the death of host cells. Systems to study the dynamics of substrate function are emerging, but additional ways to inhibit translocation at specific points during infection are required.

The Dot/Icm translocation machinery is also emerging as a model system for the study of type IV translocation in less genetically tractable organisms. For instance, recombinant strains of L. pneumophila expressing Cya fusions of ankyrin repeat-containing proteins from the obligate intracellular pathogen Coxiella burnettii translocate some of these proteins in a Dot/Icm dependent manner [20]. A recently identified substrate of the Brucella type IVA secretion system, VceC, is also ectopically translocated by the L. pneumophila in a Dot/Icm dependent manner [45]. One interpretation of these results is that the translocation signal of substrates is conserved between different type IV systems, however the possibility remains that the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm system is relatively promiscuous with regards to substrate identity. Future work on this remarkable microorganism and its complex set of translocated substrates should continue to uncover central processes involved in supporting growth of bacteria within membrane-bound compartments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Matthew Heidtman and Tamara O’Connor, along with other members of the Isberg laboratory, for helpful discussions and review of the manuscript. AWE is supported by an NRSA postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health and RRI is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Horwitz MA, Silverstein SC. Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) multiples intracellularly in human monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:441–450. doi: 10.1172/JCI109874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal G, Shuman HA. Characterization of a new region required for macrophage killing by Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5057–5066. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5057-5066.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Wong SK, Isberg RR. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •4.Vincent CD, Friedman JR, Jeong KC, Buford EC, Miller JL, Vogel JP. Identification of the core transmembrane complex of the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1278–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05446.x. This paper uses a robust set of biochemical and genetic data to show that five proteins form the core complex of the Dot/Icm type IV translocation machinery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isberg RR, O’Connor TJ, Heidtman M. The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubori T, Hyakutake A, Nagai H. Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1307–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo ZQ, Isberg RR. Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:841–846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304916101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shohdy N, Efe JA, Emr SD, Shuman HA. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4866–4871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501315102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campodonico EM, Chesnel L, Roy CR. A yeast genetic system for the identification and characterization of substrate proteins transferred into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:918–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazalet C, Rusniok C, Bruggemann H, Zidane N, Magnier A, Ma L, Tichit M, Jarraud S, Bouchier C, Vandenesch F, et al. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity . Nat Genet. 2004;36:1165–1173. doi: 10.1038/ng1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •11.de Felipe KS, Glover RT, Charpentier X, Anderson OR, Reyes M, Pericone CD, Shuman HA. Legionella eukaryotic-like type IV substrates interfere with organelle trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000117. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000117. This reference continues to dissect the function of a large number of previously identified Legionella proteins with eukaryotic-like motifs. Many of these are shown to be translocated to the host cytosol by the Dot/Icm system, and were further characterized to determine which cause vesicle trafficking defects when heterologously expressed in yeast. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Felipe KS, Pampou S, Jovanovic OS, Pericone CD, Ye SF, Kalachikov S, Shuman HA. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7716–7726. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2002;295:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien M, Morozova I, Shi S, Sheng H, Chen J, Gomez SM, Asamani G, Hill K, Nuara J, Feder M, et al. The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen. Legionella pneumophila Science. 2004;305:1966–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.1099776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagai H, Cambronne ED, Kagan JC, Amor JC, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A C-terminal translocation signal required for Dot/Icm-dependent delivery of the Legionella RalF protein to host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:826–831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406239101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanRheenen SM, Dumenil G, Isberg RR. IcmF and DotU are required for optimal effector translocation and trafficking of the Legionella pneumophila vacuole. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5972–5982. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5972-5982.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laguna RK, Creasey EA, Li Z, Valtz N, Isberg RR. A Legionella pneumophila-translocated substrate that is required for growth within macrophages and protection from host cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18745–18750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609012103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson MS. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1261–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wieland H, Goetz F, Neumeister B. Phagosomal acidification is not a prerequisite for intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila in human monocytes. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1610–1614. doi: 10.1086/382894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan X, Luhrmann A, Satoh A, Laskowski-Arce MA, Roy CR. Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors. Science. 2008;320:1651–1654. doi: 10.1126/science.1158160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conover GM, Derre I, Vogel JP, Isberg RR. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: a translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:305–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••22.Machner MP, Isberg RR. A bifunctional bacterial protein links GDI displacement to Rab1 activation. Science. 2007;318:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1149121. Together with reference 31, this paper uses biochemical and cell biological approaches to demonstrate that the Dot/Icm translocated effector, SidM/DrrA, acts as both a GEF and a GDF, driving the activation of Rab1 through this bifunctional activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habyarimana F, Al-Khodor S, Kalia A, Graham JE, Price CT, Garcia MT, Kwaik YA. Role for the Ankyrin eukaryotic-like genes of Legionella pneumophila in parasitism of protozoan hosts and human macrophages. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1460–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagan JC, Roy CR. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:945–954. doi: 10.1038/ncb883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagan JC, Stein MP, Pypaert M, Roy CR. Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1201–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagan JC, Murata T, Roy CR. Analysis of Rab1 recruitment to vacuoles containing Legionella pneumophila. Methods Enzymol. 2005;403:71–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)03007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorer MS, Kirton D, Bader JS, Isberg RR. RNA interference analysis of Legionella in Drosophila cells: exploitation of early secretory apparatus dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machner MP, Isberg RR. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev Cell. 2006;11:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murata T, Delprato A, Ingmundson A, Toomre DK, Lambright DG, Roy CR. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:971–977. doi: 10.1038/ncb1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••31.Ingmundson A, Delprato A, Lambright DG, Roy CR. Legionella pneumophila proteins that regulate Rab1 membrane cycling. Nature. 2007;450:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature06336. See reference 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •32.Heidtman M, Chen EJ, Moy MY, Isberg RR. Large-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates that modulate host cell vesicle trafficking pathways. Cell Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01249.x. This paper utilizes a directed yeast expression screen to identify a large group of confirmed or candidate Dot/Icm substrates that cause yeast growth defects and/or manipulate eukaryotic vesicle trafficking. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Luo ZQ. The Legionella pneumophila effector SidJ is required for efficient recruitment of endoplasmic reticulum proteins to the bacterial phagosome. Infect Immun. 2007;75:592–603. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01278-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirby JE, Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Isberg RR. Evidence for pore-forming ability by Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:323–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuckman DM, Hung JB, Roy CR. Pore-forming activity is not sufficient for Legionella pneumophila phagosome trafficking and intracellular growth. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:990–1001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molmeret M, Alli OA, Zink S, Flieger A, Cianciotto NP, Kwaik YA. icmT is essential for pore formation-mediated egress of Legionella pneumophila from mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:69–78. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.69-78.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Reyes M, Clarke M, Shuman HA. Host cell-dependent secretion and translocation of the LepA and LepB effectors of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1660–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belyi Y, Niggeweg R, Opitz B, Vogelsgesang M, Hippenstiel S, Wilm M, Aktories K. Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase inhibits host elongation factor 1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16953–16958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601562103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belyi Y, Tabakova I, Stahl M, Aktories K. Lgt: a family of cytotoxic glucosyltransferases produced by Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3026–3035. doi: 10.1128/JB.01798-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Losick VP, Isberg RR. NF-kappaB translocation prevents host cell death after low-dose challenge by Legionella pneumophila. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2177–2189. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abu-Zant A, Jones S, Asare R, Suttles J, Price C, Graham J, Kwaik YA. Anti-apoptotic signalling by the Dot/Icm secretion system of L. pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:246–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •42.Banga S, Gao P, Shen X, Fiscus V, Zong WX, Chen L, Luo ZQ. Legionella pneumophila inhibits macrophage apoptosis by targeting pro-death members of the Bcl2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5121–5126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611030104. This paper demonstrates that the Dot/Icm translocated substrate, SidF, is an important inhibitor of pro-apoptotic stimuli in host cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandyopadhyay P, Liu S, Gabbai CB, Venitelli Z, Steinman HM. Environmental mimics and the Lvh type IVA secretion system contribute to virulence-related phenotypes of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2007;75:723–735. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00956-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soderberg MA, Dao J, Starkenburg SR, Cianciotto NP. Importance of type II secretion for survival of Legionella pneumophila in tap water and in amoebae at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5583–5588. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00067-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •45.de Jong MF, Sun YH, den Hartigh AB, van Dijl JM, Tsolis RM. Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06487.x. Together with reference 20, this paper demonstrates that the Legionella Dot/Icm translocation system can support the translocation of heterologously expressed substrates from other type IV secretion systems. This approach may be extremely useful in the study of less genetically tractable systems. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy CR, Berger KH, Isberg RR. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abu Kwaik Y. The phagosome containing Legionella pneumophila within the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis is surrounded by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2022–2028. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2022-2028.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivanov SS, Roy CR. Modulation of ubiquitin dynamics and suppression of DALIS formation by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Cell Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coers J, Vance RE, Fontana MF, Dietrich WF. Restriction of Legionella pneumophila growth in macrophages requires the concerted action of cytokine and Naip5/Ipaf signalling pathways. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2344–2357. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zamboni DS, Kobayashi KS, Kohlsdorf T, Ogura Y, Long EM, Vance RE, Kuida K, Mariathasan S, Dixit VM, Flavell RA, et al. The Birc1e cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor contributes to the detection and control of Legionella pneumophila infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:318–325. doi: 10.1038/ni1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren T, Zamboni DS, Roy CR, Dietrich WF, Vance RE. Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zink SD, Pedersen L, Cianciotto NP, Abu-Kwaik Y. The Dot/Icm type IV secretion system of Legionella pneumophila is essential for the induction of apoptosis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1657–1663. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1657-1663.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hilbi H, Segal G, Shuman HA. Icm/dot-dependent upregulation of phagocytosis by Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:603–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]