Abstract

We integrated publicly available fiscal and budgetary data to assess historical and prospective trends in public health system funding at the federal, state, and local levels in relation to the recommended objectives outlined in the Institute of Medicine's definitive 2002 report. Although historical growth rates for public health expenditures at all levels were competitive with other major funding objects (requested or funded budget items), outlays for health care services and medical research dwarfed public health spending in absolute amounts. Competition for scarce discretionary resources, competing policy priorities, and protracted fiscal pressures will make it difficult for public health systems to achieve the recommended objectives.

Public health is often described by policymakers as an important national priority.1 From an aging population to the growing threat of pandemic influenza and other emerging infectious diseases to the burgeoning health crises of obesity and other chronic illnesses, the most persistent and costly challenges to American health and well-being fall increasingly on the public health system and on public health professionals at all levels.2

Since the seminal Future of Public Health was first published in 1988, the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) have returned repeatedly to discussion of the fragility of the public health system.3 In its 2002 reexamination of the challenges facing public health, the IOM's definitive The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century emphasized the critical role that public health agencies play in promoting health and mitigating disease burden in a heterogeneous and aging population.4 For an expanding and diverse range of social and public health challenges, the first responder is increasingly the emergency room physician, the community-based nurse, or the epidemiologist at the local public health department.5

Although it is likely that components of the public health system have strengthened over time, the IOM and other analysts emphasize the urgent need to confront significant gaps that threaten the public's health and security. According to the IOM, “the public health system that was in disarray in 1988 remains in disarray today.”6 Additional resources have become available since the IOM completed its report in 2002, principally related to biohazard and pandemic flu preparedness, but as the US Government Accountability Office and others have concluded in subsequent analyses, “much remains to be accomplished.”7

Recent assessments of the functionality and performance of the public health system identified serious deficiencies and suggested that progress has not been uniform.8 Improvements in disease surveillance, laboratory capacity, communication, and public health workforce have strengthened federal, state, and local public health agencies and improved all-hazard preparedness, but observers have identified serious challenges and areas of continuing and unresolved concern.9 The public health workforce is aging rapidly; projected retirement rates among public health professionals as high as 45% over the next 5 years and high vacancy and turnover rates will strain state and local public health systems for years to come.10 Gaps also remain in essential public health functions at the state and local level. Regional interstate planning, planning for mass vaccination and the distribution of medical supplies, and development of adequate surge capacity are incomplete or insufficient. The Government Accountability Office concluded in 2004 that “no State is fully prepared to respond to a major public health threat,” an assessment that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reiterated in 2008.11

In its recommendations to policymakers, the IOM emphasized the need to strengthen funding and support for public health agencies at all levels.12 Of its 34 recommendations, 12 dealt explicitly with increased funding for public health system infrastructure and workforce components, and roughly another third could require additional funding support, at least indirectly, to achieve their objectives.13 Hundreds of medical, nursing, public health, and patient advocacy organizations have reinforced the IOM's conclusion that further resource investments are needed to strengthen public health infrastructure and improve preparedness.14

Broad consensus among public health stakeholders supports the argument that further investments are needed to ensure a functional, resilient public health system at all levels. It is therefore worth considering carefully the extent to which legislative and administrative policymakers whose decisions shape the federal budget and influence the legislative process for appropriations have actually increased (or plan to increase) resource commitments to public health funding objects (requested or funded budget items). Public budgeting is ultimately an attempt by policymakers to coordinate and balance individual policy preferences and public goods against the limited availability of scarce public resources. How has public health fared in resource competition with other funding objects? What are the expectations for public health funding growth in the foreseeable future?

METHODS

We analyzed historical and prospective data on public health expenditures, public health–related expenditures, and comparable benchmark expenditures from several public sources. Tables 1, 2, and 3 show our data and their sources.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Historical Trends in Funding for Public Health and Other Relevant Expenditure Categories

| Percentage of Gross Domestic Producta |

Percentage of Real per Capita Expenditureabc |

Percentage of All Health Spendingde |

||||||||||||||||

| Spending Category | 30-Year Growth Rate, 1979–2008 | 20-Year Growth Rate, 1989–2008 | 10-Year Growth Rate, 1999–2008 | Pre-9/11, 1992–2001 Growth Rate | Pre-9/11, 1997–2001 Growth Rate | Post-9/11, 2002–2008 Growth Rate | 30-Year Growth Rate, 1979–2008 | 20-Year Growth Rate, 1989–2008 | 10-Year Growth Rate, 1999–2008 | Pre-9/11, 1992–2001 Growth Rate | Pre-9/11, 1997–2001 Growth Rate | Post-9/11, 2002–2008 Growth Rate | 30-Year Growth Rate, 1979–2008 | 20-Year Growth Rate, 1989–2008 | 10-Year Growth Rate, 1999–2008 | Pre-9/11, 1992–2001 Growth Rate | Pre-9/11, 1997–2001 Growth Rate | Post-9/11, 2002–2008 Growth Rate |

| Public health fundingf | ||||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary FDAf (OT) | −0.70 | 0.19 | −0.66 | −1.33 | −0.00 | −1.70 | 1.11 | 1.89 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 2.34 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Discretionary HRSAf (OT) | −1.52 | 2.68 | 0.91 | 3.26 | 2.01 | −3.11 | 0.27 | 4.42 | 2.52 | 5.61 | 4.41 | −1.34 | ||||||

| Discretionary IHSf (OT) | 0.37 | 1.27 | 0.45 | −0.25 | −2.04 | −0.92 | 2.19 | 2.99 | 2.05 | 2.01 | 0.26 | 0.88 | ||||||

| Discretionary CDCf (OT) | 5.56 | 5.95 | 6.23 | 6.13 | 4.38 | 4.59 | 7.47 | 7.75 | 7.92 | 8.55 | 6.83 | 6.49 | ||||||

| Discretionary NIHf (OT) | 1.95 | 2.34 | 3.21 | 2.75 | 5.81 | 0.38 | 3.80 | 4.07 | 4.85 | 5.08 | 8.30 | 2.20 | ||||||

| Discretionary SAMSAf (OT) | −1.64 | 0.28 | −0.64 | −5.64 | 8.61 | −3.17 | 0.14 | 1.98 | 0.94 | −3.50 | 11.15 | −1.41 | ||||||

| Discretionary health, federalf (OT) | 0.83 | 2.43 | 2.89 | 1.52 | 4.12 | 0.08 | 2.66 | 4.17 | 4.53 | 3.82 | 6.56 | 1.90 | ||||||

| Discretionary DHHSf (OT) | 0.82 | 1.76 | 2.38 | 1.37 | 3.94 | −0.47 | 2.64 | 3.48 | 4.01 | 3.67 | 6.38 | 1.34 | ||||||

| Discretionary function 550, totalf (OT) | 0.83 | 2.43 | 2.89 | 1.52 | 4.12 | 0.08 | 2.66 | 4.17 | 4.53 | 3.82 | 6.56 | 1.90 | ||||||

| Discretionary Function 551, health care servicesf (OT) | 0.84 | 4.15 | 3.32 | 2.68 | 3.38 | 0.36 | 2.67 | 5.91 | 4.97 | 5.01 | 5.80 | 2.18 | ||||||

| Public health, federalde | 2.33 | 4.43 | 6.27 | 1.97 | 3.79 | 1.64 | 4.19 | 6.19 | 7.86 | 4.18 | 5.96 | 3.47 | 0.01 | 2.48 | 3.93 | 1.07 | 2.03 | 0.00 |

| Public health, state and localde | 2.89 | 1.53 | −0.22 | 2.11 | 2.35 | −1.58 | 4.76 | 3.23 | 1.27 | 4.32 | 4.49 | 0.18 | 0.56 | −0.37 | −2.41 | 1.20 | 0.62 | −0.03 |

| Public health, combinedde | 2.78 | 1.94 | 0.68 | 2.09 | 2.52 | −1.05 | 4.65 | 3.65 | 2.19 | 4.30 | 4.66 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.03 | −1.53 | 1.19 | 0.78 | −0.02 |

| State/local grants, disease control (preventive health)g (OT) | 5.29 | 7.41 | −0.43 | 16.02 | 30.22 | −1.96 | 7.20 | 9.23 | 1.15 | 18.66 | 33.28 | −0.18 | ||||||

| Research/development, health, non-NIHg (OT) | −2.86 | −2.43 | −3.30 | −4.67 | 14.34 | −7.93 | −1.10 | −0.78 | −1.77 | −2.50 | 17.02 | −6.26 | ||||||

| Relevant benchmark expendituresf | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total defense discretionarya (OT) | −0.33 | −1.48 | 3.85 | −5.05 | −2.15 | 3.94 | 1.48 | 0.19 | 5.50 | −2.89 | 0.15 | 5.83 | ||||||

| Total nondefense discretionarya (OT) | −0.94 | 0.47 | 1.58 | −0.91 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.85 | 2.18 | 3.20 | 1.34 | 2.70 | 1.94 | ||||||

| National health expendituresde (all source) | 2.32 | 1.91 | 2.25 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 1.43 | 4.17 | 3.62 | 3.78 | 3.08 | 3.85 | 3.25 | ||||||

| Total federal health expendituresde | 3.00 | 3.06 | 3.28 | 1.55 | 1.05 | 2.46 | 4.87 | 4.79 | 4.83 | 3.75 | 3.17 | 4.30 | 0.67 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 0.65 | −0.66 | 0.01 |

| Total federal Medicare expendituresde | 3.43 | 2.98 | 3.79 | 1.45 | −0.91 | 4.03 | 5.31 | 4.71 | 5.35 | 3.65 | 1.16 | 5.90 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.51 | 0.55 | −2.59 | 0.03 |

| Total federal medicaid expendituresde | 3.69 | 4.26 | 2.17 | 2.24 | 3.39 | 0.13 | 5.57 | 6.01 | 3.71 | 4.46 | 5.55 | 1.93 | 1.34 | 2.30 | −0.07 | 1.34 | 1.64 | −0.01 |

| Total state and local health expendituresde | 2.01 | 1.80 | 1.81 | 1.25 | 2.61 | 0.62 | 3.86 | 3.51 | 3.34 | 3.45 | 4.76 | 2.43 | −0.30 | −0.10 | −0.43 | 0.36 | 0.87 | −0.01 |

| Total state and local Medicaid expendituresde | 3.77 | 4.37 | 3.31 | 4.15 | 4.67 | 2.06 | 5.65 | 6.12 | 4.86 | 6.40 | 6.86 | 3.89 | 1.42 | 2.41 | 1.04 | 3.23 | 2.89 | 0.01 |

| Total state and local health expenditures, net of Medicaidde | 0.77 | −0.02 | 0.39 | −0.75 | 0.95 | −0.79 | 2.60 | 1.66 | 1.90 | 1.40 | 3.06 | 0.99 | −1.51 | −1.89 | −1.81 | −1.63 | −0.76 | −0.02 |

| Total private health expendituresde | 2.02 | 1.32 | 1.75 | 0.45 | 1.90 | 1.01 | 3.87 | 3.02 | 3.27 | 2.62 | 4.03 | 2.82 | −0.29 | −0.58 | −0.49 | −0.44 | 0.18 | −0.00 |

| Total function 550, healthg (OT) | 3.12 | 4.31 | 2.89 | 1.99 | 3.15 | 0.89 | 4.99 | 6.08 | 4.53 | 4.31 | 5.57 | 2.73 | ||||||

| Total function 551, health care servicesg (OT) | 3.57 | 4.80 | 2.92 | 2.16 | 2.97 | 1.03 | 5.45 | 6.58 | 4.56 | 4.49 | 5.39 | 2.86 | ||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, nondefenseg (OT) | −0.05 | 1.99 | 1.23 | 1.18 | 2.57 | −0.61 | 1.76 | 3.72 | 2.84 | 3.48 | 4.98 | 1.19 | ||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, healthg (OT) | 3.48 | 4.43 | 2.41 | 2.14 | 3.45 | 0.20 | 5.35 | 6.20 | 4.05 | 4.46 | 5.88 | 2.03 | ||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, health, net of Medicaid/SCHIPg (OT) | −0.74 | 2.68 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 10.02 | −1.79 | 1.06 | 4.42 | 2.47 | 2.99 | 12.61 | −0.01 | ||||||

| Total federal research and development, nondefenseg (OT) | −1.26 | 0.20 | 0.62 | −1.92 | −1.36 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 1.90 | 2.23 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 2.26 | ||||||

| Total federal research and development, healthg (OT) | 1.60 | 2.04 | 3.00 | 1.75 | 6.61 | 0.08 | 3.44 | 3.77 | 4.65 | 4.06 | 9.12 | 1.90 | ||||||

Note. 9/11 = September 11, 2001; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; OT = outlay funding category; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IHS =Indian Health Service ; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH = National Institutes of Health; SAMSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; DHHS = Department of Health and Human Services; SCHIP = State Children's Health Insurance Program. Funding annualized with compound annual growth rate and displayed as a percentage. Zero values are below the rounding threshold but are non-zero.

Congressional Budget Office, Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2009 and related tables.15

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2008.16

Adjusted with the implicit price deflator for gross domestic product (FY2000 = $100.00). Price index source: Congressional Budget Office, 2008.17

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Accounts.18

Not reported in Budget Authority/Outlay/Program Level categories.

Public Budget Database, Office of Management and Budget, February 2008.19

Fiscal Year 2009 President's Budget, February 2008.20

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Prospective Trends in Funding for Public Health and Other Relevant Expenditure Categories

| President's Request/National Health Expenditure Estimates |

Congressional Budget Office Baseline |

|||||||||||||||||

| Percentage of Gross Domestic Producta |

Percentage of Real Per Capita Expenditureabc |

Percentage of All Health Spendingde |

Percentage of Gross Domestic Producta |

Percentage of Real Per Capita Expenditureabc |

Percentage of All Health Spendingde |

|||||||||||||

| 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | 1-Year Growth Rate, 2008–2009 | 5-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2013 | Out-Year Growth Rate, 2009–2017 | |

| Public health funding | ||||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary FDAf (OT) | 19.50 | 20.76 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary HRSAf (OT) | −3.25 | −2.22 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary IHSf (OT) | −4.61 | −3.60 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary CDCf (OT) | −10.44 | −9.49 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary NIHf (OT) | −1.52 | −0.48 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary SAMSAf (OT) | −7.05 | −6.07 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary health, federalg (OT) | −2.00 | −0.97 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary DHHSf (OT) | −6.01 | −5.02 | ||||||||||||||||

| Discretionary function 550, totala (OT) | −2.56 | −6.27 | −1.53 | −4.08 | −0.91 | −3.76 | 0.13 | −1.51 | ||||||||||

| Discretionary function 551, health care servicesa (OT) | −3.24 | −6.31 | −2.22 | −4.12 | −1.03 | −4.55 | 0.02 | −2.32 | ||||||||||

| Public health, federalde | 6.87 | 5.26 | 5.17 | 8.43 | 7.70 | 7.21 | 4.25 | 3.80 | 3.30 | |||||||||

| Public health, state and localde | 1.86 | 1.00 | 1.48 | 3.35 | 3.34 | 3.45 | −0.64 | −0.41 | −0.31 | |||||||||

| Public health, combinedde | 2.76 | 1.84 | 2.25 | 4.27 | 4.20 | 4.23 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.44 | |||||||||

| State/local grants, disease control (preventive health)g (OT) | −3.60 | −2.58 | ||||||||||||||||

| Research/development, health, non-NIHg (OT) | 0.56 | 1.63 | ||||||||||||||||

| Relevant benchmark expenditures | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total defense discretionarya (OT) | 2.80 | −7.85 | 3.89 | −5.69 | −7.33 | −4.81 | −6.35 | −2.59 | ||||||||||

| Total nondefense discretionarya (OT) | −2.00 | −6.26 | −0.97 | −4.07 | −1.97 | −3.46 | −0.93 | −1.21 | ||||||||||

| National health expendituresde (all-source) | 2.52 | 1.41 | 1.80 | 4.01 | 3.76 | 3.78 | ||||||||||||

| Total federal health expendituresde | 2.91 | 2.01 | 2.57 | 4.42 | 4.38 | 4.56 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.75 | |||||||||

| Total federal Medicare expendituresde | 3.21 | 2.04 | 2.63 | 4.72 | 4.41 | 4.62 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.81 | |||||||||

| Total federal Medicaid expendituresde | 3.12 | 2.48 | 3.02 | 4.63 | 4.86 | 5.02 | 0.59 | 1.06 | 1.19 | |||||||||

| Total state and local health expendituresde | 2.08 | 1.40 | 1.92 | 3.57 | 3.75 | 3.90 | −0.42 | −0.01 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| Total state and local Medicaid expendituresde | 3.21 | 2.63 | 3.16 | 4.72 | 5.01 | 5.16 | 0.68 | 1.20 | 1.33 | |||||||||

| Total state and local health expenditures, net of Medicaidde | 0.86 | −0.03 | 0.40 | 2.33 | 2.29 | 2.35 | −1.62 | −1.42 | −1.38 | |||||||||

| Total private health expendituresde | 2.37 | 1.03 | 1.27 | 3.86 | 3.37 | 3.24 | −0.15 | −0.38 | −0.52 | |||||||||

| Total function 550, healtha (OT) | 1.45 | 0.59 | 2.52 | 2.94 | 2.55 | 1.13 | 3.63 | 3.49 | ||||||||||

| Total function 551, health care servicesa (OT) | 1.76 | 1.32 | 2.83 | 3.69 | 2.97 | 1.64 | 4.06 | 4.02 | ||||||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, nondefenseg (OT) | −1.62 | −2.67 | −0.58 | −0.40 | ||||||||||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, healthg (OT) | 1.60 | 1.73 | 2.67 | 4.11 | ||||||||||||||

| Total federal grants to states/local communities, health, net of Medicaid/SCHIPg (OT) | −9.93 | −8.40 | −8.98 | −6.25 | ||||||||||||||

| Total federal research and development, nondefenseg (OT) | −1.20 | −0.15 | ||||||||||||||||

| Total federal research and development, healthg (OT) | −1.13 | −0.08 | ||||||||||||||||

Note. FDA = Food and Drug Administration; OT = outlay funding category; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IHS = Indian Health Service; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH = National Institutes of Health; SAMSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; DHHS = Department of Health and Human Services; SCHIP = State Children's Health Insurance Program. Funding annualized with compound annual growth rate and displayed as a percentage. “Out-year” refers to beyond the prospective, or currently requested, fiscal year expenditures.

Congressional Budget Office, Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2009 and related tables.15

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2008.16

Adjusted with the implicit price deflator for gross domestic product (FY2000 = 100.00) Price index source: Congressional Budget Office (2008).17

Office of the Actuary, National Health Expenditure Accounts.18

Not reported in Budget Authority, Outlay, or Program Level categories.

Public Budget Database, Office of Management and Budget, February 2008.19

Fiscal Year 2009 president's budget (February 2008).20

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Growth Rates in Department of Health and Human Services Programs and Core Funding Levels

| Percentage of Gross Domestic Producta |

Percentage of Real per Capita Expenditureabc |

|||||||

| FY2008–2009, Req Growth Rate | FY1998–2008, Growth Rate | FY1998–2009, Req Growth Rate | FY2001–2002, Growth Rate | FY2008–2009, Req Growth Rate | FY1998–2008, Growth Rate | FY1998–2009, Req Growth Rate | FY2001–2002, Growth Rate | |

| Total expendituresd | ||||||||

| FDA | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 14.2 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 14.3 |

| HRSA | −17.5 | 1.3 | −0.6 | −0.2 | −16.6 | 3.0 | 1.1 | −0.1 |

| CDC | −7.9 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 49.5 | −6.9 | 10.2 | 8.5 | 49.8 |

| NIH | −3.6 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 11.2 | −2.6 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 11.4 |

| Core fundingdefg | ||||||||

| FDA | 0.05 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| HRSA | −17.5 | 1.3 | −0.6 | −2.3 | −16.6 | 3.0 | 1.1 | −2.2 |

| CDC | −8.0 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 2.1 | −7.0 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 2.2 |

| NIH | −3.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 10.1 | −2.6 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 10.3 |

Note. FY = fiscal year; Req = requested; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH = National Institutes of Health. Funding annualized with the compound annual growth rate. Growth comparisons are based on program-level agency funding data, a more inclusive (and as a result, more conservative) budget presentation. Table includes President's FY09 Budget Request. Core funding excludes biopreparedness funding for illustrative pro forma purposes—some observers have questioned whether biopreparedness funding directly or fully contributes to basic or essential public health activities.

Congressional Budget Office, Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2009 and related tables.15

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2008.16

Adjusted with the implicit price deflator for gross domestic product (FY2000 = $100.0). Price index source: Congressional Budget Office (2008).17

US Department of Health and Human Services, Budget in Brief, 1999 to 2008.21

Public Budget Database, Office of Management and Budget, February 2008.19

Bioterrorism: Federal Research and Preparedness Activities, Government Accountability Office, GAO-01-915 (September 2001).22

Franco and Deitch, “Billions for biodefense.”23

Except where indicated, our analyses incorporated or referred to so-called baseline budget data, drawn from the current Congressional Budget Office (CBO) discretionary baseline (as of this writing, the CBO had most recently updated its baseline in March 2008).24 Most of the relevant nonentitlement health-related programs were itemized under budget function 550 (health) and in particular, budget subfunction 551, which collected expenditure data for the CDC and other federal public health funding objects. Except where indicated, we did not attempt to adjust for various legislative and fiscal priorities that Congress may consider adopting (expiring tax cuts, out-year [beyond the prospective, or currently requested, fiscal year] war costs, proposed entitlement and tax policy reforms, and so on).

Other data relevant to public health and other health issues were drawn from the National Health Expenditure (NHE) Accounts data set compiled by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services,25 Office of Management and Budget supplemental budget information,26 and supplemental tables included in the president's fiscal year 2009 budget submission and subsequent amendments.27

This article was completed in April 2008, after Congress had reached a final resolution on fiscal year 2008 appropriations legislation. Except where indicated, our analysis incorporated funding data that included both fiscal year 2008 enacted and fiscal year 2009 requested supplemental appropriations funding to provide a clearer comparison of actual and requested discretionary funding levels.

Except where indicated, federal, state, and local funding levels are presented in outlay reporting categories, depending on data availability. Every effort was made to incorporate comparable fiscal and budgetary data over identical accounting intervals, although in certain instances we reported expenditure trend analysis or growth rates according to either federal or state fiscal or calendar year reporting conventions, as available. The divergence in public reporting standards diminished the precision of single-year or small-interval comparisons across dissimilar expenditure data sets, although funding growth magnitude, rate, and trajectory over multiple years were, for our purposes, broadly comparable.

We present alternative indicators—percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), real per capita expenditure (fiscal year or calendar year 2000 = 100.0), and percentage of all US health expenditures—for the benefit of readers who may find different analytic metrics more useful for comparative or reporting purposes. Relative changes in annualized expenditures were calculated on an annually compounded basis using the compound annual growth rate formula (calculating the nth root of total growth, where n is the number of years) and are presented in the accompanying tables.

RESULTS

Federal Public Health Spending

Historical trends.

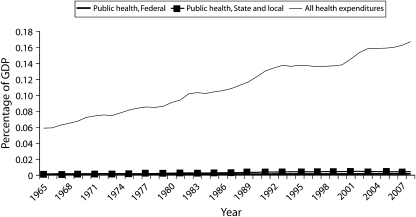

Although longer-term annualized growth in NHE estimates of broad public health funding at the federal level is competitive with other major funding objects and relevant benchmarks on both nominal and adjusted bases, total funding for health care services and medical research dwarfs federal public health funding in absolute amounts (Table 1 and Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of public health expenditures to all US health expenditures: 1965–2008.

Note. GDP = gross domestic product.

Source. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2008.

Viewed as a percentage of GDP and real per capita expenditures, federal public health spending declined, beginning in the early 1970s through 1986, before climbing relatively steadily throughout the 1990s. In 2002, additional appropriations were allocated in the wake of the attacks of September 11, 2001, and bioterrorism-related concerns that significantly increased the rate of growth for this category. Over 30 years (1979–2008), federal public health spending underperformed a number of other US health sector expenditure categories overall; as a percentage of all US health expenditures, federal public health spending was lower in 2008 than it was in 1966.

When we estimated disaggregated, or core, federal public health spending by omitting recent preparedness and pandemic influenza–related expenditures, federal public health spending at the agency level for the CDC and certain other Public Health Service agencies moderated significantly as annualized expenditure growth slowed consistently across public health agency budgets (Table 3).

Outlook.

In fiscal year 2009, discretionary function 550 expenditures included in the president's budget request were −2.6%/−1.5% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) below fiscal year 2008 expenditure estimates. Growth over fiscal years 2009 to 2013 for this category was anticipated by the administration to be −6.3%/−4.1% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure).29 The president requested that fiscal year 2009 discretionary CDC outlays decline −10.4%/−9.5% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) from the previous year's levels (Table 2).

More broadly, the president requested that federal nondefense discretionary expenditures decline at an annualized −2.0%/−1.0% rate (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) in fiscal years 2008 to 2009 and −6.3%/−4.1% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) in fiscal years 2009 to 2013. Out-year costs associated with fighting wars and with terrorism-preparedness initiatives were not included in this projection and are likely to further reduce total federal funding available for nondefense discretionary purposes.30 By contrast, NHE estimates projected consistent growth in public health expenditures at all levels of government in fiscal years 2008 to 2009 and in fiscal years 2009 to 2017, despite the president's request for reduced nondefense discretionary spending for next-year (the immediately prospective fiscal year) and out-year intervals. NHE's future public health spending projections are estimated endogenously and extrapolate a post–September 11 rate of growth that may be difficult to sustain over time.31

Congressional action on the fiscal year 2009 appropriations legislation was not complete at this writing, although administration representatives from the Office of Management and Budget expressed the president's intention to veto any legislation that exceeded his requested fiscal year 2009 discretionary total of $991.6 billion.32 The continuing debate over war-related issues, the competition among domestic priorities outside the health sector, and the impending election of a new administration—potentially with new priorities—make predictions about public health–related funding at the federal level uncertain.

Federal Public Health Research and Development Spending

Historical trends.

Federal spending on health-related research and development apart from the National Institutes of Health, a category that includes public health and is reported in subfunction 552, has oscillated over time with little consistent long-term growth. Measured as a percentage of GDP, this type of spending peaked in 1980 (0.03%) and as real per capita spending in 1992 ($7.81). Annualized funding growth in the 10-year trailing interval was negative (−3.3%/−1.8% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]). Funding for this type increased less than for its closest benchmark (total federal research and development, health) over the 10-, 20-, and 30-year trailing intervals measured as either percentage of GDP or real per capita spending.

Outlook.

Out-year projections for this funding object beyond fiscal year 2009 were not available. Although total nondefense research and development expenditures were requested at a rate of −1.2%/−0.2% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) over fiscal years 2008 to 2009, and total health-related federal research and development spending was requested at −1.1%/−0.1% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) over the same period, research and development expenditures in the health category (separate from expenditures for the National Institutes of Health) were requested to increase by 0.6%/1.6% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure). Flat fiscal year 2008 to 2009 spending levels would further compound the effects of deep reductions in this category in fiscal years 2007 to 2008 (−19.6%/−18.6% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]).

Federal Grants to State and Local Governments for Disease Prevention

Historical trends.

Federal spending to support state and local disease prevention activities—including public health education, workforce training, and maintaining data, surveillance, and laboratory systems—grew moderately and relatively consistently until 1999, when funding for this object jumped 130.9%/138.3% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) over the previous year's outlay.

Spending growth for state and local disease prevention grants was substantially greater than for benchmark objects over the 20- and 30-year trailing average growth rate measured as either percentage of GDP or real per capita expenditure, but was lower over the 10-year interval. Annualized growth in the 10-year trailing interval was weak (−0.4%/1.2% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]) and considerably less robust than in the 5-year interval before September 11 (30.2%/33.3% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]).

Outlook.

Out-year projections for this funding object beyond fiscal year 2009 were not available. Federal expenditures in fiscal year 2009 for grants to state and local governments for disease control (preventive health) were requested at −3.6%/−2.6% (percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure) over fiscal year 2008 levels, following substantial reductions in fiscal years 2006 to 2007 (−26.1%/−24.8% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]) and fiscal years 2007 to 2008 (−4.0%/−2.8% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]). The fiscal year 2008 request for this category was consistent with the requested levels for comparable benchmarks.

However, the benchmark federal expenditures for grants to state and local governments for health, adjusted to exclude anticipated Medicaid and State Children's Health Insurance Program funding, would decline over fiscal years 2008 to 2009 (−9.9%/−9.0% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]) and fiscal years 2009 to 2013 (−8.4%/−6.3% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]) intervals, which could adversely affect disease prevention funding at the state and local levels (where reductions in categorical funding under one object may offset funding growth in others).

State and Local Public Health Funding

Historical trends.

NHE data since 1965 indicated that public health outlays at the state and local level grew relatively consistently on both nominal and adjusted bases, with strong growth in fiscal year 2002 after September 11 followed by a period of slower growth relative to fiscal year 2002 levels over the fiscal years 2003 to 2004—probably a recession-linked phenomenon—before recovering somewhat in the following years.

The category was competitive with certain benchmarks (e.g., longer-term federal nondefense discretionary spending growth) but was generally less well funded over the 10-year trailing interval. Spending in this category grew more slowly than did federal public health spending over the trailing 10- and 20-year intervals. State and local public health expenditures grew more rapidly over the trailing 30-year interval because of generally higher growth rates throughout fiscal years 1979 to 1986.

As with federal public health spending, the difference in magnitude in aggregate public health spending at the state and local levels relative to other categories of health-related spending was significant. In fiscal year 2008, real per capita state and local public health spending was only $149.33 Total federal health spending per capita was $2181; total state and local health spending was $818 per capita.

Viewed as a percentage of total all-source US health spending over the past 3 decades, state and local public health spending grew relatively consistently until the late 1990s, peaking in fiscal year 1999 and declining 19.7% through fiscal year 2008.

Outlook.

Unlike the president's relatively straightforward consolidated budget request for federal expenditures, next-year and out-year estimates of state and local public health spending were more difficult to assess. The NHE projected that public health expenditures at the state and local level would grow at a significantly slower rate than federal public health funding levels over fiscal years 2008 to 2009 (1.9%/3.4% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]), fiscal years 2009 to 2013 (1.0%/3.3% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]), and fiscal years 2009 to 2017 (1.5%/3.5% [percentage of GDP/real per capita expenditure]). Note that the NHE's endogenous projections may not have fully captured potential changes in federal, state, and local public health funding trends.

The National Governors Association and National Association of State Budget Officers estimated that nominal state general fund spending in state fiscal year 2007 grew by 9.3% over levels in previous years, rebounding after a series of tough budget cycles to a higher rate than the 30-year average of 6.4%.34 However, the fiscal and revenue outlook for state and local budgets has grown considerably darker as the national economy has soured.

Analysts for the National Governors Association and National Association of State Budget Officers reported in December 2007 that “while revenue growth was generally strong in [state] fiscal 2007, [state] fiscal 2008 enacted budgets reflect more modest growth, and some states have already reported budget shortfalls.”35 The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities' state fiscal monitoring project estimated in March 2008 that combined state fiscal year 2009 deficits totaled at least $48 billion in 29 states and the District of Columbia, with another 3 states facing budget gaps in state fiscal year 2010, and the number “of states facing budget gaps is likely to grow as state revenue forecasts are updated during the legislative session.”36 Other observers have broadly confirmed the negative outlook for state and local budgets for at least the year ahead.37

Fiscal and revenue constraints will likely continue to limit state-level discretionary resources available for discretionary objects such as public health.38 Public health spending has tended to fall below state policymakers' highest budgetary priorities, suggesting that discretionary expenditures for public health may lag behind entitlement-driven health care spending.39 In its most recent state budget update, the National Conference of State Legislatures determined that state revenue growth is slowing; real adjusted state tax revenue was estimated to have fallen by 4.3% in the fourth quarter relative to prior-year levels.40

DISCUSSION

Public health professionals, working with state and local health departments, laboratories, and other public health organizations, play a vital and increasingly central role in protecting our health. Yet the CDC and other public health observers have repeatedly identified deficiencies in public health infrastructure, workforce, and planning that compromise all-hazard readiness—systemic problems that remain unresolved today.41

Observers have laid much of the blame for the current, suboptimal state of public health infrastructure, systems, and workforce on the lasting effects of historic underfunding.42 Although we made no effort to determine the accuracy of that assertion, we concluded that public health funding objects have received significantly less funding in absolute amounts at all levels of government than have relevant discretionary benchmark funding objects.

In the 10-year interval before September 11, 2001, federal public health expenditures averaged a modest 0.05% of GDP (1.1% of federal expenditures for health care; 0.4% of total US expenditures for health care). When we examined changes in spending since September 11 (fiscal years 2002–2008), we found that mean annual federal public health expenditures increased by $5.7 billion, or 140.8%, but still averaged only 0.08% of GDP (1.5% of federal expenditures for health care; 0.5% of total US expenditures for health care).

State and local budgets for public health grew substantially less than did comparable federal expenditures after September 11. Comparison of adjusted expenditures over the periods preceding and following September 11 indicates that average real per capita state and local public health spending grew by only about one fourth as much as federal public health spending, and annualized growth rates at the state and local level actually declined (from 4.3% before September 11 to 0.2% after; this compares with federal growth rates of 4.2% and 3.5%, respectively).

Federal public health spending grew competitively with key benchmarks, but the differences in absolute amounts were substantial: federal public health expenditures over the trailing 10-year interval averaged only 0.5% of all-source US health care spending, or $26 mean real per capita expenditure, versus $5579 mean real per capita expenditure for all-source US health care spending. State and local public health expenditures averaged only 2.6% of mean all-source US health care spending, or $142 real per capita expenditure, over the trailing 10-year interval.

Although growth rates as a percentage of GDP for federal public health expenditures strengthened in the immediate wake of September 11—a welcome development—annualized growth in discretionary outlays at the CDC ultimately declined (6.1% to 4.6% [percentage of GDP], comparing pre– and post–September 11 trailing intervals), as did federal grants to state and local governments for disease prevention–related activities (16.0% to −2.0% [percentage of GDP]). State and local public health funding growth also slowed appreciably (2.1% to −1.6% [percentage of GDP]).

Growth in federal public health expenditures declined significantly when we isolated biodefense and preparedness funding and compared annualized growth rates in the remaining core funding (Table 3). This finding engages the larger question of the extent to which new funding associated with post–September 11 biopreparedness expenditures concurrently strengthen federal and state and local public health systems, infrastructure, and response capacity—so called dual-use or all-hazard preparedness—beyond the targeted objectives that relate solely to bioterrorism threat reduction.43 Observers who examined this question closely have identified areas of meaningful progress in public health systems, infrastructure, and response capacity associated with the new funding, but they also found that critical challenges remained.44 As we gain more information about post–September 11 public health expenditures over time, this phenomenon will require careful monitoring and additional analysis.

Public Health Funding Outlook

The outlook for public health systems at all levels of government is challenging. Credible and potentially synergistic threats, ranging from the emerging risk of infectious disease and bioterror to burgeoning rates of lifestyle-mediated chronic illnesses, appear to be increasing, but the resources needed to combat these hazards are in relatively short supply. Among the 15 highest-priority risk-based federal emergency planning scenarios—potential disasters or terrorist-strike events that the Department of Homeland Security disseminated to state and local governments—all but 1 were incidents that would inevitably involve federal and other public health agencies, officials, laboratories, and hospitals as either primary first respondents or essential members of coordinated team respondents.45

Yet the funding needed to support federal, state, and local preparedness for these high-priority threats may not be available in the near term. Given the limitations on data and projections available, we could only assess the outlook for the coming decade, although these issues may persist much longer. Prospective budgetary challenges include structural deficits that could persist through fiscal year 2018. The CBO's baseline budget projections assume no change in current law and forecast a cumulative fiscal year 2009 to 2018 budget surplus totaling $270 billion over the 10-year interval.46 Over the same interval however, the president's fiscal year 2009 budget request was projected to result in net cumulative deficits of $717 billion through fiscal year 2018.47 These projected imbalances, coupled with the president's commitments to reduce the tax burden without substantially affecting entitlement growth, would put significant pressure on nondefense discretionary outlays.48 The CBO observed that discretionary funding under the president's budget could be expected to decline significantly, dropping by 10% in inflation-adjusted terms by 2013.49

Despite the enactment of substantial supplemental appropriations that increased aggregate discretionary expenditure totals in fiscal year 2008,50 these funds were essentially unavailable for domestic public health funding objects. Instead, after excluding funds associated with ongoing military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and with hurricane relief, the president's fiscal year 2009 nondefense budget request reflected an overall decline of 0.5% from fiscal year 2008 levels.51

Waging war and funding war recovery in the Persian Gulf region could affect baseline nondefense discretionary spending and deficits for several years, diverting resources away from public health funding objects.52 The CBO's slower and potentially more realistic phase-down estimate projected an even larger cumulative outlay through fiscal year 2018.53

Limited Discretionary Funds, Competing Priorities

Nondefense discretionary spending is likely to be constrained. Although the CBO is projecting long-term growth in mandatory outlays, baseline nondefense discretionary spending—where Public Health Service agencies such as the CDC draw their funding—is projected to decline as a percentage of total outlays (from 17.7% to 13.1%) and also as a percentage of GDP (from 3.7% to 2.5%) by fiscal year 2018. Supplemental appropriations for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and other defense activities totaled $171 billion in fiscal year 2007; $105 billion and $70 billion in additional supplemental funding was requested by the president for fiscal years 2008 and 2009 (in addition to the $88 billion in war-related expenditures already appropriated in fiscal year 2008).54

Other policy priorities will compete for scarce revenue. The CBO's baseline estimates assume that popular tax cuts will be allowed to expire as scheduled, principally in 2010, an outcome that some observers do not expect.55 By contrast, the president's fiscal year 2009 budget proposed $2.2 trillion in additional net tax expenditures through fiscal year 2018,56 including permanent extension of expiring dividend and capital gains reductions, repeal of federal estate and gift taxes, and extension of certain other expiring tax provisions.57 Congress has identified other priority tax expenditures, including substantial reform of the Alternative Minimum Tax; the CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation have estimated reform of the alternative minimum tax would incur approximately $913 billion in net reductions in federal revenue through fiscal year 2018.58

Other policy priorities may also affect federal budgets, constraining discretionary funding available for public health. Congress has appropriated $691 billion in discretionary budget authority since September 2001 associated with the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and the global war on terrorism.59 The CBO's estimate did not include additional future-year funding associated with hurricane recovery efforts in the US Gulf Coast region, despite widespread reports that additional expenditures will be needed.60

Budget analysts have also noted with concern the long-term budgetary risks associated with entitlement-related expenditure growth, especially rising health care costs in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In the CBO's assessment, “[T]he United States continues to face severe long-term budgetary challenges… . If current laws and policies remained in place, federal spending on [Medicare and Medicaid] alone would rise from 4.6% of GDP in 2007 to about 12% by 2050 and 19% by 2082. That percentage represents about the same share of the economy that the entire federal budget does today.”61 The health care director of the Government Accountability Office, A. Bruce Steinwald, described the entitlement trajectory in stark terms: “[T]he federal budget is on a path that is fiscally unsustainable… . Mandatory spending … threatens to crowd out discretionary spending for a vast array of domestic programs.”62

Funding Growth Limited at State and Local Level

States also face significant fiscal challenges. Analysts caution that states and local communities face considerable fiscal pressures both in the coming fiscal year and in the longer term and may not be able to easily replace declining federal funding for core public health activities.63 With state tax revenues weakening in the face of a softening economy, states are less confident that revenue projections will meet or exceed forecasts.64 Key economic and revenue indicators are cooling or mixed, increasing the risk that tax revenues may fall short of forecasters' projections, and states are facing what analysts for the National Governors Association and the National Association of State Budget Officers describe as growing “demands for increased funding of programs [like] Medicaid … and looming long-term issues such as funding pensions, demographic shifts, and maintenance and repair of infrastructure”—priorities that may take precedence over other discretionary functions and exacerbate deficiencies in public health infrastructure and preparedness.65

Public health and other purely discretionary expenditures may appear to be nonessential to state and local lawmakers facing competing fiscal and budgetary pressures, including Medicaid cost growth (estimated at 7.3% in state fiscal year 2007), states' share of costs associated with the new Medicare prescription drug benefit, recent administrative constraints associated with the State Children's Health Insurance Program and uncertainty about its reauthorization, and demographic changes that include growth in elderly and uninsured populations.66

Finally, structural characteristics unique to state budgets, including the requirement to balance state budgets annually and the rising share of expenditures devoted to health care services, education, and other politically well-defended programs, could diminish the total resources available for public health.67

Uncertain Prospects For Public Health

Despite relatively robust projections for NHE federal public health expenditure growth, the outlook for public health funding at all levels of government is uncertain.68 At the agency level, the CDC in particular faces significant challenges in its efforts to achieve its core objectives, including strengthening public health infrastructure, developing the public health workforce, and increasing investments in health system preparedness. CDC director Julie Gerberding estimated in 2008 that $15 billion in annual CDC funding is needed to ensure that the agency can execute its responsibilities effectively (confirming an earlier 5-year projection of the funding level needed to meet key agency objectives).69 The necessary growth rate under the most conservative estimate consistent with the director's projection (5-year growth, fiscal year 2008 base) to reach $15 billion implies an annualized growth rate of 13.0%.

Federal funding for public health activities at the state and local levels is similarly constrained. Although the NHE projects weakly positive growth for state and local public health spending, those estimates are lower than expected federal growth rates and may not fully reflect the significant challenges facing state and local governments. It seems likely that public health–related activities will continue to occupy a relatively low status among the competing priorities for state and local governments facing entitlement and demographic pressures, recessionary revenues, countercyclical spending projections and structural budgetary challenges into the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Many policymakers agree that an efficient and highly functional public health system is an important national priority for the 21st century.70 Public health systems that manage various, often competing responsibilities effectively will exert a positive influence on a wide range of public health priorities, both acute and chronic. Yet most observers also agree that the public health system, although more important than ever, is severely stressed at every level and needs further attention.

The critical and pervasive challenges to American public health, identified by the IOM and others, are unlikely to be resolved quickly or fully until significant new resources are dedicated to strengthening public health infrastructure, capacity, and workforce development. A broad, diverse coalition of medical, public health, and patient advocacy organizations has worked collaboratively in recent years to strengthen the public health system and to significantly increase public funding for the federal Public Health Service (and indirectly, funding for state and local grantees), a collective effort that is continuing into the fiscal year 2009 budget and appropriations cycle.71

Despite the commitment of these groups and the urgent challenges facing our public health system, competing discretionary funding priorities in a recessionary budget year will make this goal extremely difficult to achieve. Public health advocates should expect that the future of public health, much like its past, will be marked by constrained federal, state, and local funding levels and a persistent lack of commitment to the public's health.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge CARE and the American Academy of Pediatrics for the support they provided in allowing us to prepare and submit this article for publication.

Human Participant Protection

No human participants were involved in the research reported in this article.

Endnotes

- 1. See, for example, National Governors Association (NGA), Policy Position: HHS-04. Public Health Services Policy (Washington, DC: NGA, 2006); George W. Bush, “Avian and Pandemic Influenza” (November 1, 2005, transmittal letter designating administration proposals for $7.1 billion in funding for influenza preparedness-related purposes), http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/amendments/supplemental_11_01_05.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008)

- 2. Amanda Navarro et al, “Charting the Future of Community Health Promotion: Recommendations from the National Expert Panel on Community Health Promotion,” Preventing Chronic Disease 4, no. 3 (2007): 1–7; House Committee on Government Reform, A Review of This Year's Flu Season: Does Our Public Health System Need a Shot in the Arm?, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., February 12, 2004 (serial no. 108–143), 109–112, testimony of Karen Miller on behalf of the National Association of Counties. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Institute of Medicine (IOM), The Future of Public Health (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1988); IOM, Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1992); IOM, Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003); IOM, Research Priorities in Emergency Preparedness and Response for Public Health Systems (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2008)

- 4. IOM, The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2002) [PubMed]

- 5.Maria G. Sistrom, Patty J. Hale, “Outbreak Investigations: Community Participation and Role of Community and Public Health Nurses,” Public Health Nursing 23 (2006): 256–63; Julie Gerberding, James Hughes, and Jeffrey Koplan, “Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response: Clinicians and Public Health Agencies as Essential Partners,” Journal of the American Medical Association of America (JAMA) 287 (2002): 898–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IOM, Future of Public Health, 100. See also Tommy Thompson, “For Mass-Casualty Preparedness, Congress Should Fund ‘ER One,’” The Hill, December 6, 2006. Asked to assess the challenges associated with disaster preparedness, the former Health and Human Services secretary stated, “More than five years after Sept. 11, 2001, no state is adequately prepared for a potential mass-casualty disaster caused by a terrorist attack, pandemic or natural disaster.”

- 7. House Committee on Government Reform, A Review of This Year's Flu Season: Does Our Public Health System Need a Shot in the Arm?, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., February 12, 2004 (serial no. 108–143), 63–73, testimony of Janet Heinrich, on behalf of the Government Accountability Office (GAO); House Committee on Government Reform, The Next Flu Pandemic: Evaluating U.S. Readiness, 109th Congress, 1st sess., June 30, 2005 (serial no. 109–49), 107–125, testimony of Marcia Crosse on behalf of the GAO, 2005; G. Caleb Alexander, G. Luke Larkin, and Matthew K. Wynia, “Physicians’ Preparedness for Bioterrorism and Other Public Health Priorities,” Academic Emergency Medicine 13, no. 11 (2006): 1238–41, Epub 2006 Apr 13; NGA Center for Best Practices, Pandemic Preparedness in the States: An Interim Assessment from Five Regional Workshops (Washington, DC: NGA, 2008), 1–2; Trust for America's Health (TAH), Our Vision for a Healthier America (Washington, DC: TAH, 2008) (public statement signed by 121 health and community organizations: “[T]oday, serious gaps exist in the nation's ability to safeguard health, putting our families, communities, states and nation at risk”), http://healthyamericans.org/policy/files/VisionHealthierAmerica.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008)

- 8. National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), Federal Funding for Public Health Emergency Preparedness: Implications and Ongoing Issues for Local Health Departments (Washington, DC: NACCHO, 2007); IOM, Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006), 201; Jeanne Lambrew and Donna Shalala, “Federal Health Policy Response to Hurricane Katrina, What it Was and What it Could Have Been,” JAMA 296 (2006): 1394–97; Sara Rosenbaum, “US Health Policy in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,” JAMA 295 (2006): 437–39; P. Gregg Greenough and Thomas D. Kirsch, “Hurricane Katrina: Public Health Response—Assessing Needs,” NEJM 353 (2005): 1544–46; Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Challenges for the People of New Orleans: The Kaiser Post-Katrina Baseline Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2007); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Key Findings From Public Health Preparedness: Mobilizing State by State (Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2008), 5.

- 9. See, for example, Michael Osterholm, “Preparing for the Next Pandemic,” New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) 352 (2005): 1839–42; Sarah A. Lister and Holly Stockdale, Pandemic Influenza: An Analysis of State Preparedness and Response Plans (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2007) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), State Public Health Employee Worker Shortage Report: A Civil Service Recruitment and Retention Crisis (Washington, DC: ASTHO, 2004), 2–3.

- 11. Heinrich, 2004 testimony, 63; CDC, Public Health Preparedness: Mobilizing State by State (Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2008), 27; NGA Center for Best Practices, Pandemic Preparedness in the States: An Interim Assessment from Five Regional Workshops (Washington, DC: NGA, 2008), 1–2; NACCHO, Federal Funding; Terri Rebmann et al., “Hospital Infectious Disease Emergency Preparedness: A Survey of Infection Control Professionals,” American Journal of Infection Control 35, no. 1 (2007): 25–32. See also Bradford H. Gray and Kathy Hebert, After Katrina: Hospitals in Hurricane Katrina: Challenges Facing Custodial Institutions in a Disaster (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2006): 14–19; American College of Emergency Physicians, The National Report Card on the State of Emergency Medicine (Washington, DC: American College of Emergency Physicians, 2006), 1–2; Office of the Inspector General, Memorandum Report—Laboratory Preparedness for Pandemic Influenza (Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 2007), 1–2.

- 12. IOM, Future of Public Health, 144.

- 13. Ibid., 4–17.

- 14. American Medical Association (AMA), Resolution H-440.892, Bolstering Public Health Preparedness, Proceedings of the AMA House of Delegates, 2001 Interim Meeting, 389 (Chicago, IL: AMA); AMA, Resolution H-440.954, Revitalization of Local Public Health Units for the Nation, Proceedings of the AMA House of Delegates, 2007 Annual Meeting, 399 (Chicago, IL: AMA); AMA, H-440.982, Centers for Disease Control Funding, Proceedings of the AMA House of Delegates, 2005 Annual Meeting, 346 (Chicago, IL: AMA); AMA, D-440.997, Support for Public Health, Proceedings of the AMA House of Delegates, 2003 Annual Meeting, 257 (Chicago, IL: AMA); Coalition for Health Funding, “It's Time to Make Public Health Funding a National Priority” (Washington, DC: Coalition for Health Funding, 2008) (letter to members of Congress signed by more than 400 health organizations urging increased funding for function 550 programming in fiscal year 2009), http://www.aamc.org/advocacy/healthfunding/correspondence/021908.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008)

- 15. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2009, Budget Projections: supplemental data tables (Washington, DC: CBO, 2008): 4 [also incorporates unpublished data provided by CBO to us]

- 16. Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2008)

- 17. CBO, Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals, 2008 (unpublished table)

- 18. CDC, National Health Expenditure Accounts: Definitions, Sources, and Methods 2006 (Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2008)

- 19. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Public Budget Database, February 2008, http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2009/db.html (accessed July 25, 2008)

- 20. OMB, Fiscal Year 2009 President's Budget (Washington, DC: OMB, 2008), supplementary tables (table 27-1, historical tables 3.2, 8.7, 9.8, 12.2, 12.3)

- 21. DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 1999), pp 18–44, 94–99; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2000), pp 21–50, 117–120; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2001), pp 15–50, 100; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2002), pp 15–47, 99–105; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2003), pp 10–38, 93–94; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2004), pp 12–40, 105–106; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2005), pp 12–42, 113; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2006), pp 16–40, 99–101; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2007), pp 15–39, 102–109; DHHS, Budget in Brief (Washington, DC: DHHS, 2008), pp 14–40, 105–111.

- 22. GAO, Bioterrorism: Federal Research and Preparedness Activities (Washington, DC: GAO, September 2001), GAO-01-915.

- 23. Crystal Franco and Shana Deitch, “Billions for Biodefense: Federal Agency Biodefense Funding, FY2007–FY2008,” Biosecurity and Bioterrorism 5 (2007): 117–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24. Except where indicated, for prospective analysis we relied on unofficial baseline projections adjusted by the CBO to remove out-year supplemental funding otherwise required to be repeated in the official CBO baseline.

- 25. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Health Expenditure Data, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData (accessed April 6, 2008)

- 26. We obtained out-year projections (fiscal years 2010–2013) for the president's budget from unpublished CBO data tables associated with the March 2008 CBO reestimate of the president's fiscal year 2009 budget request.

- 27. See OMB, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2009, http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2009, and OMB, Supplementals, Amendments and Releases, http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/amendments.htm (accessed April 6, 2008). Note that much of our analysis focuses on budget function 550 (health) and budget subfunctions 551, 552, and 554. This budget function captures discretionary and mandatory federal expenditures for health care services (SF 551), health-related research and training programs (SF 552), and consumer and occupational health and safety programming (SF 554). CBO, Budget Options (Washington, DC: CBO, 2007), 145.

- 28. CMS, National Health Expenditure Accounts, 2008.

- 29.CBO, Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals, 3.; For years after 2009, the President's budget is presented in less detail. For discretionary spending, the request for 2010 through 2013 is provided only in aggregate terms (which CBO used to calculate funding totals for defense and nondefense spending), and the budget does not contain year-by-year estimates of spending and revenues after 2013. It does, however, specify the total effect of proposed changes in laws affecting taxes and mandatory spending for the 10-year period through 2018. To determine the impact of the President's proposals, CBO, with assistance from JCT [the Joint Committee on Taxation], developed its own estimates for policies affecting revenues and mandatory spending. It estimated discretionary outlays for the 2014–2018 period by projecting the amount of discretionary budget authority that the President recommended for 2013 and adjusting that amount for inflation.

- 30. Note that $291 billion in supplemental and emergency discretionary funding for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and other activities related to the war on terrorism was appropriated in fiscal years 2006 and 2007 ($120 billion in 2006 and $171 billion in 2007). The president further requested supplemental and emergency funding totaling $193 billion in fiscal year 2008 (of which $88 billion had been appropriated as of this writing) and requested another $70 billion in fiscal year 2009. CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2008 to 2018 (Washington, DC: CBO, 2008), Box 1–1; CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, 17.

- 31. See Office of the Actuary, Projections of National Health Expenditures: Methodologies and Model Specification (Washington, DC: CMS, 2008), 14; Office of the Actuary, National Health Expenditure Accounts, 14–15.

- 32. “Nussle Threatens Vetoes Before Dem Budgets Unveiled,” Congress DailyPM, March 3, 2008.

- 33. National Health Expenditure (NHE) per capita estimates are roughly consistent with 2005 survey-derived state and local spending estimates in Leslie M. Beitsch et al., “Public Health at Center Stage: New Roles, Old Props,” Health Affairs 25 (2006): 917–22.

- 34. NGA and National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), The Fiscal Survey of the States: December 2007 (Washington, DC: NGA and NASBO, 2007), viii.

- 35. Ibid.

- 36.Elizabeth C. McNichol, Iris J. Lav, 29 States Face Total Budget Shortfall of at Least $48 Billion in 2009(Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2008), 3 [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL), State Budget Update: April 2008 (Washington, DC: NCSL, 2008); NCSL, Changes in State Tax Collections, 2000 to 2007, Quarterly (Washington, DC: NCSL, 2008); Jennifer Steinhauer, “As the Economy Falters, So Do State Budgets,” New York Times, sec. A, March 17, 2008; Stan Dorn et al., Medicaid, SCHIP and Economic Downturn: Policy Challenges and Policy Responses (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2008)

- 38. NCSL, State Budget Update, 2008.

- 39. NCSL, State Budget Update: March 2007 (Washington, DC: NCSL, 2007), Tables 5 and 6, 18–23 (identifying probable use of unexpected resources in fiscal years 2007 and 2008); NGA Center for Best Practices, The Governors Speak—2008: An Interim Report on the State-of-the-State Addresses of 25 Governors (Washington, DC: NGA, 2008), 9–10. Within health care, governors significantly focused on coverage for the uninsured, health issues associated with children, and health care costs. Forty percent (10 of 25 governors) “highlighted wellness, prevention, and early intervention programs focused on promoting healthy lifestyles and detecting diseases and conditions early.” GAO, State and Local Governments: Growing Fiscal Challenges Will Emerge During the Next 10 Years (Washington, DC: GAO, 2008), 5–6.

- 40. NCSL, State Budget Update, 2008, 1; Lucy Dadayan and Robert B. Ward, “State Tax Revenue Weakens Still Further, While Costs Rise Sharply,” State Revenue Report 72 (March 2008): 1.

- 41. Julie Gerberding, CDC, Professional Judgment [Budget] for Fiscal Year 2008, submitted to the US House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health, and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies, April 2007; TAH, Ready or Not? Protecting the Public's Health from Diseases, Disasters and Bioterrorism (Washington, DC: TAH, 2007); GAO, Influenza Pandemic: Further Efforts Are Needed to Ensure Clearer Federal Leadership Roles and an Effective National Strategy (Washington, DC: GAO, 2007); GAO, Influenza Pandemic: Opportunities Exist to Address Critical Infrastructure Protection Challenges That Require Federal and Private Sector Coordination (Washington, DC: GAO, 2007); GAO, Letter Report to The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson et al., Subject: Public Health and Hospital Emergency Preparedness Programs: Evolution of Performance Measurement Systems to Measure Progress, March 23, 2007; NACCHO, Federal Funding.

- 42. IOM, Future of Public Health, 143.

- 43. Thomas May and Ross Silverman, “Bioterrorism Defense Priorities,” Science 301 (2003): 17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. TAH, Ready or Not?; Aaron Katz, Andrea B. Staiti, and Kelly L. McKenzie, “Preparing for the Unknown, Responding to the Known: Communities and Public Health Preparedness,” Health Affairs 24 (2006): 946–57; Julie Gerberding, Professional Judgment; CDC, Key Findings, 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45. Eric Lipton. “US Lists Possible Terror Attacks and Likely Toll,” New York Times, sec. A, March 16, 2005.

- 46. CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, Table 1-1.

- 47. Ibid.

- 48. Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “Bush Presents Budget That Would Increase Deficit,” New York Times, sec. A, February 5, 2008.

- 49. CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, 17.

- 50. See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008, Public Law 110–161, 110th Cong., 1st sess. (December 26, 2007)

- 51. CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, 16.

- 52. House Budget Committee, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: What Will Be the Long-Term Effect on the Federal Budget, 110th Cong., 1st sess., August 2, 2007 (serial no. 110–18), 12–21, testimony of Stanley J. Czerwinski on behalf of the GAO; House Budget Committee, The Growing Budgetary Costs of the Iraq War, 110th Cong., 1st sess., October 24, 2007 (serial no. 110–22), 9–22, testimony of Peter Orszag on behalf of the CBO.

- 53. CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, Table 1-5. Table estimates were updated subsequent to publication by the CBO. Note that a more rapid force drawdown would incur a net savings in discretionary outlays relative to current baseline estimates (first scenario)

- 54. Ibid., Box 1-1; CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, 16.

- 55. See, for example, Anna Bernasek, “Economic View: ‘Temporary’ Tax Cuts Have a Way of Becoming Permanent,” sec. B, New York Times, May 14, 2006.

- 56. Net total includes both Joint Committee on Taxation estimates of reduced revenues through fiscal year 2018 attributable to newly proposed changes to the tax code and increased mandatory outlays for refundable tax credits. CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, 9.

- 57. Joint Committee on Taxation, Description of Revenue Provisions Contained in the President's Fiscal Year 2009 Budget Proposal (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2008); CBO, President's Budgetary Proposals, Table 1–3.

- 58. CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, Table 1-5.

- 59. Ibid., Box 1-1.

- 60. Paul A. Singer, “Hurricane Season: Port in a Storm,” National Journal 38, no. 21 (May 27, 2006): 1422–26; Czerwinski, testimony.

- 61. CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, xi, 18.

- 62. GAO, Health Care Spending: Public Payers Face Burden of Entitlement Program Growth, While All Payers Face Rising Prices and Increasing Use of Services (Washington, DC: GAO, 2007)

- 63. Donna Stone et al. on behalf of the National Conference of State Legislatures, letter to the Honorable Harry Reid et al., January 18, 2008 (“[S]tates are facing budget challenges due to the slowing national economy … more [states] are expected to face serious budget gaps as they progress further into their fiscal years”); GAO, State and Local Governments.

- 64. NGA, Economic Stimulus: a State Perspective (Washington, DC: NGA, 2008), 1–2. (“Although the nation is at the beginning of a downturn, 17 states already face shortfalls totaling $14 billion in 2008 and 15 states project shortfalls of $30 billion for 2009. History suggests both the number of states facing shortfalls and the severity will grow even after the downturn ends.”)

- 65. NGA and NASBO, Fiscal Survey of the States, viii; NCSL, State Budget Update, 2008; GAO, State and Local Governments; GAO, State and Local Government Retiree Benefits: Current Funded Status of Pension and Health Benefits (Washington, DC: GAO, 2008)

- 66. NGA and NASBO, Fiscal Survey of the States, 5; NGA, Policy Position EC-13: The Medicare Drug Benefit (Washington, DC: NGA, 2007), 13.2; Senate Finance Committee, Covering Uninsured Children: the Impact of the August 17 CHIP Directive, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., April 9, 2008; Alan R. Weil, testimony on behalf of the National Academy for State Health Policy; Vernon K. Smith, Barbara Coulter Edwards, and Jennifer Tolbert, Current Issues in Medicaid: A Mid-FY2008 Update Based on a Discussion with Medicaid Directors (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2008)

- 67. NCSL, State Budget Actions FY2006 and FY2007 (Washington, DC: NCSL, 2007); GAO, State and Local Governments, 1–6.

- 68. “Nussle Threatens Vetoes,” Congress DailyPM.

- 69. Campaign for Public Health, “CDC Director Again Calls for $15 Billion Agency Budget,” Update (Winter 2008), http://www.fundcdc.org/documents/CPHUpdateFinal1Q08.pdf (accessed July 25, 2008); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Professional Judgment Budget for Fiscal Year 2006, submitted to the US House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies, March 2006, 8.

- 70. See, for example, Bill Frist, “Public Health and National Security: The Critical Role of Increased Federal Support,” Health Affairs 21 (2002): 117–30; Joseph R. Biden, “America Is Not Ready to Respond to a National Health Emergency,” The Hill, May 10, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71. Trust for America's Health, Our Vision for a Healthier America (Washington, DC: TAH, 2008), public statement signed by 121 health and community organizations, http://healthyamericans.org/policy/files/VisionHealthierAmerica.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008); Coalition for Health Funding, It's Time to Make Public Health Funding a National Priority (Washington, DC: CHF, 2008), letter to members of Congress signed by more than 400 health organizations urging increased funding for function 550 programming in fiscal year 2009, http://www.aamc.org/advocacy/healthfunding/correspondence/021908.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008); Campaign for Public Health, letter to the Honorable David Obey et al. (sent to congressional appropriators from more than 400 health organizations urging increased funding for the CDC) (Washington, DC: CPH, 2007), http://www.fundcdc.org/documents/PDFofFY08signonletterAppropsCommitteemembersFINAL_000.pdf (accessed April 6, 2008)