Abstract

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is a debilitating condition reported after chronic steroid use. The purpose of this study was to describe the magnitude of risk in individuals who survived one or more years after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), and to investigate the role of immunosuppressive agents such as prednisone, tacrolimus (FK506), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and cyclosporine (CSA) in the development of AVN after HCT. Using a retrospective study design, we followed 1,346 eligible patients for the development of AVN. Cumulative incidence was calculated taking into consideration competing risk from death and relapse. Cox proportional regression techniques were used to identify associated risk factors. The median age at HCT was 34 years (range, 7 months–69 years), and median length of follow-up for those alive was 8.2 years. Seventy-five patients developed AVN of 160 joints. The cumulative incidence of AVN at 10 years was 2.9% after autologous HCT, 5.4% after allogeneic matched related donor HCT, and 15% after unrelated donor HCT (p<0.001 compared to autologous HCT recipients). For allogeneic transplant recipients, male sex (RR=2.1, 95% CI, 1.1–4.0), presence of chronic GvHD (RR=2.2) and exposure to CSA, FK506, prednisone and MMF rendered patients at increased risk, especially in patients with a history of exposure to three or more drugs (RR=9.2, 95%CI, 2.42–35.24). Future studies examining the pathogenetic mechanism underlying AVN should help develop targeted interventions to prevent this chronic debilitating condition.

INTRODUCTION

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the bone is a painful and debilitating condition that develops when the blood supply to the bone is disrupted, usually in areas with terminal circulation. The condition is believed to be the result of vascular compromise, the death of bone and cell tissue, or disruption of bone repair mechanisms.1–4 AVN has been reported after conventional therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), particularly after exposure to dexamethasone between the ages of 10 and 20 years.5–7

AVN has also been reported as a complication of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), causing significant morbidity and often requiring surgery. Previous studies have identified graft versus host disease (GvHD), older age, primary diagnosis of acute leukemia, TBI-based conditioning regimens, and steroid therapy as significant risk factors in patients undergoing allogeneic HCT.8–15 However, these studies have been limited by reliance on small cohorts of allogeneic HCT recipients.10, 14, 15 Although a few small studies have examined the possible role of cyclosporine (CSA) in the development of AVN after HCT,9, 16 the role of the more recently used immunosuppressive agents, such as tacrolimus (FK506) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has not been examined.

In the current study, we followed 1,346 consecutive patients who had undergone HCT at City of Hope National Medical Center (COH) and survived one or more years. Our aim was to describe the magnitude of risk of AVN after autologous or allogeneic HCT, and to examine the role of specific immunosuppressive agents in the development of AVN after allogeneic HCT.

METHODS

Subjects and data collection

A retrospective cohort study design was used. All consecutive patients who had undergone autologous or allogeneic HCT at COH between 1976 and 1997 for a hematological malignancy or severe aplastic anemia, had survived at least one year post-transplantation, and were free of AVN at the time of entry into the cohort were included in this study. A Long-term Follow-up (LTFU) data collection form was completed for all patients meeting eligibility criteria. The form captured information beginning one year post-transplantation through the date of last contact. Medical records maintained at COH were the primary source of data for completion of the LTFU form. If the date of last hospital/clinic visit recorded in the medical records was not recent, or if there were any unexpected gaps in the patients’ history within the time window of interest, a standard protocol was used to identify and contact physicians taking care of patients outside COH to obtain pertinent information. If the physician was not available or unable to provide recent information, the patient was called directly. This method of follow-up ensured that information regarding clinically symptomatic disease (AVN) was captured in an uninterrupted fashion, from one year post-HCT to the date of last contact with a healthcare provider. The Human Subjects Committee at COH approved the protocol. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Information collected on the LTFU form included demographics, disease status, medication, hospitalization, vaccination history, and post-HCT complications including new malignancies, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, renal compromise, neurological toxicity, AVN, gastrointestinal complications, cataracts and details regarding GvHD. Data from the LTFU form was merged with data from an institutional database on HCT containing information on conditioning for HCT and GvHD prophylaxis/treatment.

Our cohort consisted of all 1,346 consecutive patients who met the eligibility criteria. This cohort was followed through March 2005. From the LTFU database, cases of AVN diagnosed by a healthcare provider after the first year of HCT were identified. The medical records of all patients with AVN were reviewed and confirmation of the diagnosis was collected using diagnostic radiology (plain X-rays, MRI, bone scan and/or CT scan) or surgical report(s). Details regarding management of AVN were also collected.

Statistical Analysis

Cumulative incidence, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for development of AVN after HCT was calculated taking into consideration competing risk from death and recurrence of primary disease.17 The time at risk was computed from date of transplantation to the date of onset of first episode of AVN, the date of last contact, date of death, or date of recurrence of primary disease, whichever occurred first. Cumulative incidence (with 95% CIs), for surgical intervention for AVN was calculated taking into consideration competing risk from death.17 The time at risk was computed from the date of onset of AVN, to the date of surgery, date of last contact, or date of death, whichever occurred first. Cox proportional hazard regression method was used to estimate relative risks (RR) and their 95% CIs.18 Univariate analyses for all pertinent variables were first performed to estimate RR individually. Variables examined in the Cox regression model included year of transplantation (1976 to 1985 [referent group], 1986 to 1990, 1991 to 1997), age at transplantation (<35 years [referent group], ≥35 years), race (Caucasian [referent group], Hispanic, others), type of transplantation (autologous HCT [referent group], allogeneic related donor HCT, unrelated donor HCT), and primary diagnosis (referent group: AML, CML, AA, other malignancies; comparison group: ALL, NHL, HL, MM). The primary diagnoses were grouped to create a comparison group that would contain patients potentially at a higher risk for AVN because of exposure to steroids for management of their disease. Other variables examined included agents used for conditioning (total body irradiation [TBI], cyclophosphamide, melphalan, busulfan, etoposide, cytarabine, and carmustine), presence of or history of chronic GvHD (yes, no), and exposure to immunosuppressive agents used for GvHD prophylaxis and/or treatment. The major drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/ treatment for the study cohort included methotrexate, systemic prednisone, CSA, FK506, MMF. In order to examine the role of CSA, systemic prednisone, FK506 and MMF, we combined these agents into the following composite variables: no CSA; exposure to CSA alone (without exposure to prednisone, FK506 or MMF); exposure to CSA and prednisone; exposure to CSA, prednisone, and MMF; exposure to CSA, prednisone, and FK506, and finally, exposure to CSA, prednisone, FK506 and MMF. The majority of patients receiving no CSA received methotrexate alone for GvHD prophylaxis.

Stepwise regression was employed to select important variables from those that approached statistical significance in the univariate analysis. A p-value of less than 0.10 was used as the selection criterion. Multivariate Cox regression was then performed for the selected variables to obtain adjusted RRs and 95% CIs. Analyses were conducted for the entire cohort, and stratified by the type of HCT (autologous transplant recipients only, and allogeneic transplant recipients only). All tests of statistical significance were 2-sided; and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The clinical characteristics of the patient population are summarized in Table 1. Of the 1,346 patients in this cohort, 793 (59%) were males. Median age at transplantation was 34 years (range, 7 months to 69.1 years). As of March 2005, 883 patients (66%) were alive at last contact, and the median length of follow-up for these patients was 8.2 years (range, 1 to 25.3 years). The major indications for transplantation were AML (n=335), NHL (n=299), CML (n=230), HL (n=169), ALL (n=178), MM (n=61), AA (n=56) and other miscellaneous diagnoses (n=18). Six hundred and seventy-one (50%) patients received grafts from HLA-matched or partially matched family member donors; 81 (6%) received grafts from unrelated donors matched for HLA-phenotype, and 594 (44%) patients underwent autologous transplantation. The main agents used for conditioning included cyclophosphamide (73%), TBI (75%), etoposide (69%), carmustine (11%), busulfan (9%), melphalan (3%), and cytarabine (5%). Among allogeneic transplant recipients, chronic GvHD was diagnosed in 419 patients (56%). Multiple drugs were used for GvHD prophylaxis and/or treatment, including CSA (82%), methotrexate (66%), prednisone (74%), FK506 (8%), and MMF (4%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patient population

| Total (N=1346) |

Patients with AVN (N=75) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Year of transplant | ||||||

| 1976–1985 | 177 | (13) | 6 | (8) | ||

| 1986–1990 | 256 | (19) | 17 | (23) | ||

| 1991–1997 | 913 | (68) | 52 | (69) | ||

| Age at HCT (years) | ||||||

| < 35 | 726 | (54) | 46 | (61) | ||

| ≥ 35 | 620 | (46) | 29 | (39) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 793 | (59) | 57 | (76) | ||

| Female | 553 | (41) | 18 | (24) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 857 | (64) | 45 | (60) | ||

| African American | 33 | (3) | 3 | (4) | ||

| Hispanic White | 342 | (25) | 23 | (31) | ||

| Asian | 84 | (6) | 4 | (5) | ||

| Other | 30 | (2) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Primary diagnosis | ||||||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 335 | (25) | 23 | (31) | ||

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 299 | (22) | 11 | (15) | ||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 230 | (17) | 12 | (16) | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 178 | (13) | 10 | (13) | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 169 | (13) | 11 | (15) | ||

| Multiple myeloma | 61 | (5) | 5 | (6) | ||

| Aplastic anemia | 56 | (4) | 2 | (3) | ||

| Other | 18 | (1) | 1 | (1) | ||

| Chemotherapeutic agents used for conditioning | ||||||

| Cyclophosphamide | 988 | (73) | 53 | (71) | ||

| TBI | 1013 | (75) | 57 | (76) | ||

| Etoposide | 928 | (69) | 50 | (67) | ||

| Carmustine | 147 | (11) | 8 | (11) | ||

| Busulfan | 122 | (9) | 9 | (12) | ||

| Melphalan | 44 | (3) | 0 | |||

| Cytarabine (Ara-C) | 72 | (5) | 1 | (1) | ||

| Type of HCT | ||||||

| Autologous | 594 | (44) | 20 | (27) | ||

| Allogeneic | 752 | (56) | 55 | (73) | ||

| Related | 671 | (50) | 44 | (59) | ||

| Unrelated | 81 | (6) | 11 | (14) | ||

| Status at last contact | ||||||

| Alive | 883 | (66) | 57 | (76) | ||

| Dead | 463 | (34) | 18 | (24) | ||

| Drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/treatment (allogeneic HCT only) | ||||||

| Cyclosporin A (CSA) | 614 | (82) | 52 | (95) | ||

| Tacrolimus (FK506) | 57 | (8) | 16 | (29) | ||

| Methotrexate | 493 | (66) | 36 | (65) | ||

| Prednisone | 558 | (74) | 49 | (89) | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) | 31 | (4) | 9 | (16) | ||

| Chronic graft vs. host disease | 419 | (56) | 45 | (82) | ||

Seventy-five patients developed AVN one or more years post-HCT. Of these, 44 patients had received grafts from HLA-matched or partially matched family member donors; 11 from unrelated donors, and 20 had received autologous transplants. In total, 160 joints were affected including 106 hips, 26 knees, 19 shoulders, 2 ankles, 4 wrists, and 3 elbows. The median number of affected joints per patient was 2 (range 1–8). The median latency from date of transplantation to AVN development was 3.2 years, ranging from 1 year to 16.6 years.

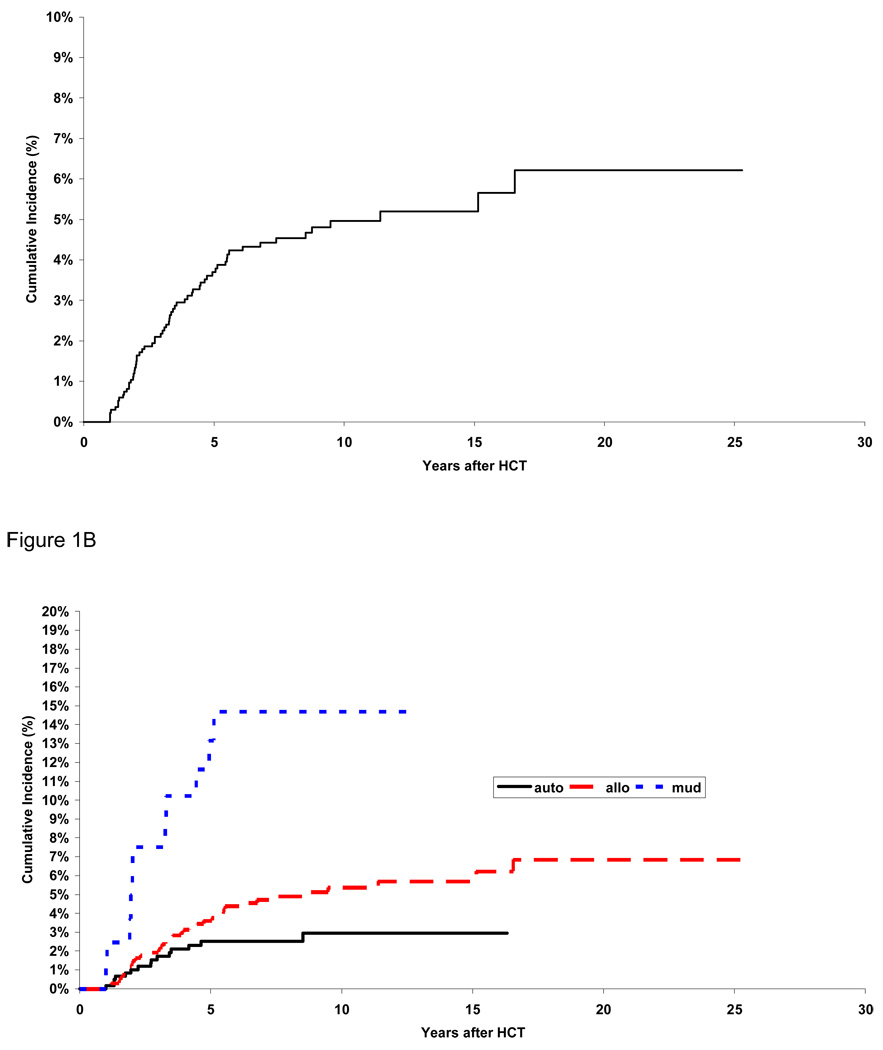

As shown in Figure 1A, the cumulative incidence of AVN was 3.7% (95% CI, 2.7% to 4.7%) at five years from HCT and 5.0% (95% CI, 3.7% to 6.2%) at 10 years. Figure 1B shows the cumulative incidence of AVN by type of transplantation. The cumulative incidence was lowest for autologous HCT recipients (2.5% at 5 years and 2.9% at 10 years), intermediate for matched related allogeneic HCT recipients (3.6% at 5 years and 5.4% at 10 years, p=0.05 compared to autologous HCT recipients), and highest for unrelated HCT recipients (13.2% at 5 years and 14.7% at 10 years, p<0.001 compared to autologous HCT recipients). Among allogeneic HCT recipients, the cumulative incidence was 2.8% for female and 5.8% for male at 5 years post-HCT (p=0.01). The corresponding figures for autologous HCT recipients, were 1.2% for female and 3.5% for males (p=0.06).

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of AVN: in the entire cohort (1A) and by type of hematopoietic cell transplant (1B)

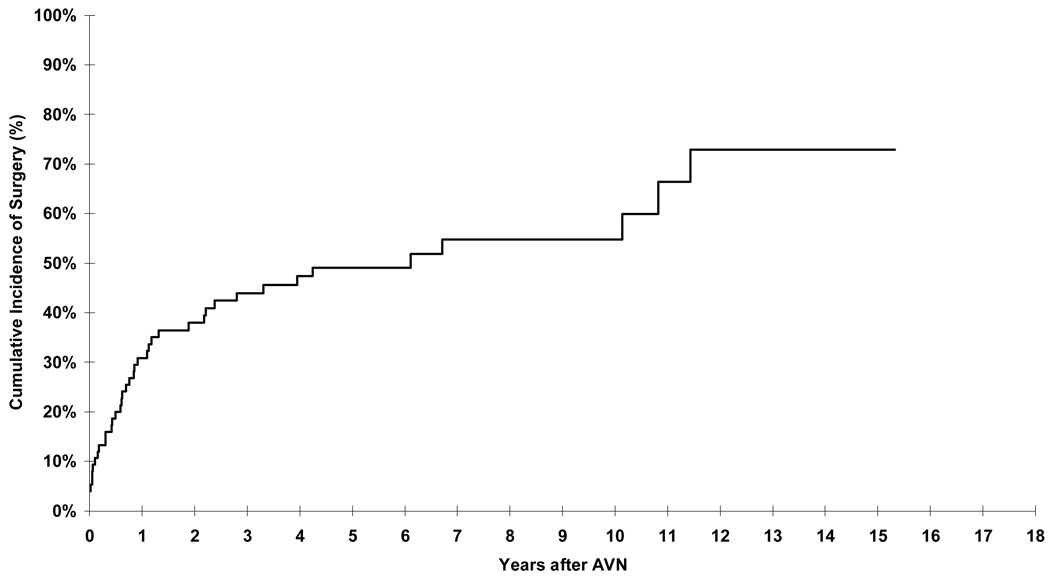

Of the 75 patients with AVN, 40 underwent surgery for management of AVN. The cumulative incidence of surgery was 30.9% (95% CI, 20.3% to 41.5%) at 1 year from AVN diagnosis (Figure 2). Arthroplasty was needed to replace 64 affected joints (40% of all affected joints); an additional nine joints (5.6%) required either drilling or placement of pins.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of surgical interventions in patients diagnosed with AVN.

Risk Factors for AVN – Entire Cohort

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate analyses for the association between AVN and demographic and clinical factors, and drugs used for prophylaxis and/or treatment of GvHD. For the entire cohort, univariate analyses identified HCT performed after 1985, male gender, and allogeneic transplantation as risk factors for development of AVN. Exposure to specific chemotherapeutic agents or TBI used for conditioning was not associated with an increased risk of AVN (data not shown). The final multivariate analysis (Table 3) revealed matched related (RR=2.4, 95% CI, 1.30–4.36, p<0.001) or unrelated (RR=5.8, 95% CI, 2.58–13.11, p<0.001) donor HCT, HCT performed after 1985, and male gender (RR=2.3, 95% CI, 1.33–3.85, p=0.002) to be independently associated with an increased risk of AVN after HCT.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical factors and the risk of delayed AVN: Univariate Analysis

| Total | Autologous HCT | Allogeneic HCT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number with /without AVN |

RR (95% CI) | Number with /without AVN |

RR (95% CI) | Number with /without AVN |

RR (95% CI) | |

| Year of transplant | ||||||

| 1976–1985 | 6/171 | 1.00 | – | 6/171 | 1.00 | |

| 1986–1990 | 17/239 | 2.65 (0.99–7.09) | 5/97 | 1.00 | 12/142 | 3.00 (1.07–8.40) |

| 1991–1997 | 52/861 | 2.73 (1.08–6.92) | 15/477 | 0.70 (0.25–1.93) | 37/384 | 4.00 (1.55–10.35) |

| Age at transplant (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 46/680 | 1.00 | 11/211 | 1.00 | 35/469 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 35 | 29/591 | 0.86 (0.54–1.37) | 9/363 | 0.52 (0.22–1.27) | 20/228 | 1.32 (0.76–2.29) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 18/535 | 1.00 | 5/251 | 1.00 | 13/284 | 1.00 |

| Male | 57/736 | 2.35 (1.39–4.00) | 15/323 | 2.32 (0.84–6.37) | 42/413 | 2.33 (1.25–4.35) |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 45/812 | 1.00 | 12/429 | 1.00 | 33/383 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic White | 23/319 | 1.19 (0.72–1.96) | 7/88 | 2.74 (1.08–6.97) | 16/231 | 0.77 (0.42–1.39) |

| African- American/Asian/Other |

7/140 | 0.90 (0.41–1.99) | 1/57 | 0.62 (0.08–4.76) | 6/83 | 0.87 (0.36–2.07) |

| Type of transplant | ||||||

| Autologous | 20/574 | 1.00 | ||||

| Related donor | 44/627 | 1.59 (0.93–2.71) | 44/627 | 1.00 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 11/70 | 4.30 (2.06–8.98) | 11/70 | 2.74 (1.40–5.33) | ||

| Primary diagnosis | ||||||

| AML/CML/AA/others | 38/601 | 1.00 | 2/109 | 1.00 | 36/492 | 1.00 |

| ALL/NHL/HL/MM | 37/670 | 1.02 (0.65–1.60) | 18/465 | 2.14 (0.50–9.23) | 19/205 | 1.37 (0.78–2.38) |

| Drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/ treatment (allogeneic HCT only) | ||||||

| No CSA | 3/128 | 1.00 | ||||

| CSA alone | 3/68 | 2.33 (0.47–11.67) | ||||

| CSA + PSE | 31/443 | 4.17 (1.24–14.05) | ||||

| CSA + PSE+MMF | 2/8 | 12.38 (2.02–75.94) | ||||

| CSA+PSE+FK506 | 9/25 | 18.42 (4.85–69.98) | ||||

| CSA+PSE+FK506+MMF | 7/14 | 19.77 (4.99–78.36) | ||||

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||||

| cGvHD (allogeneic HCT only) | ||||||

| No | 10/306 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 45/374 | 4.16 (2.09–8.28) | ||||

CSA denotes cyclosporine, MMF denotes mycophenolate mofetil, FK506 denotes tacrolimus, and GvHD denotes graft vs. host disease.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical factors and risk of AVN: Multivariate Analysis

| Overall RR (95% CI) |

Allogeneic RR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Type of transplant | ||

| Autologous | 1.00 | – |

| Related donor | 2.39 (1.30–4.36) | 1.00 |

| Unrelated donor | 5.82 (2.58–13.11) | 1.67 (0.82–3.43) |

| Year of transplant | ||

| 1976–1985 | 1.00 | – |

| 1986–1990 | 3.19 (1.20–8.53) | – |

| 1991–1997 | 3.22 (1.25–8.35) | – |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 2.26 (1.33–3.85) | 2.10 (1.12–3.95) |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||

| AML/CML/AA/others | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ALL/NHL/HL/MM | 1.55 (0.93–2.59) | 1.58 (0.90–2.77) |

| Drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/ treatment | ||

| No CSA | – | 1.00 |

| CSA alone | – | 2.26 (0.45–11.32) |

| CSA + prednisone | – | 2.62 (0.74–9.28) |

| CSA + prednisone + MMF | – | 5.17 (0.78–34.39) |

| CSA+prednisone+FK506 | – | 9.83 (2.34–41.23) |

| CSA+prednisone+FK506+MMF | – | 7.98 (1.76–36.18) |

| P for trend | – | <0.001 |

| Presence of chronic GvHD | ||

| No | – | 1.00 |

| Yes | – | 2.22 (1.02–4.82) |

AA denotes aplastic anemia, AML denotes acute myeloid leukemia, ALL denotes acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CML denotes chronic myeloid leukemia, HL denotes Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL denotes non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and MM denotes multiple myeloma.

CSA denotes cyclosporine, MMF denotes mycophenolate mofetil, FK506 denotes tacrolimus, and GvHD denotes graft vs. host disease.

Risk Factors for AVN – by type of transplantation

For autologous transplant recipients, no independent risk factors were identified. For allogeneic HCT survivors, in the univariate analysis, HCT performed after 1985, male gender, unrelated donor HCT, presence of chronic GvHD, and combinations of three or more drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/treatment, were associated with increased risk of AVN (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis for allogeneic HCT recipients, male gender, combinations of three or more drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis/treatment, and the presence of chronic GvHD were associated with increased risk of AVN (Table 3). Compared to women, men had a higher risk of AVN (RR=2.1, 95% CI, 1.12 to 3.95, p=0.01). Presence of chronic GvHD (RR=2.2, 95% CI, 1.02 to 4.82, p=0.05) and history of exposure to CSA, FK506, PSE and MMF independently rendered patients at increased risk of AVN, especially in patients exposed to three or more drugs (RR=9.2, 95% CI, 2.42 to 35.25, p=0.001). Since the number of patients exposed to MMF was relatively small, we analyzed the data after excluding these patients. Exposure to CSA, FK506 and PSE together rendered patients at increased risk of AVN (RR=8.9, 95% CI, 2.13 to 37.46, p=0.003), when compared with patients exposed to no CSA.

DISCUSSION

Of the 1,346 patients that underwent HCT and survived at least one year free of the outcome of interest, we found the cumulative incidence of AVN to be 3.7% at five years, and 5% at 10 years after transplantation. Unrelated donor HCT recipients were at increased risk of developing AVN compared to autologous HCT recipients. Among allogeneic HCT recipients, the risk of AVN was increased in male patients; those diagnosed with chronic GvHD, or those exposed to at least three or more of the following drugs: prednisone, CSA, FK506, and MMF.

AVN results from impairment of circulation to the affected bone. The femoral head is affected most frequently. Systemic steroids have long been attributed to predisposing a patient to AVN, 19–21 either by development of fat emboli in the microvasculature of the affected bone or by fatty infiltration of the marrow. Increased intraosseous pressure, intravascular coagulation, venous stasis, and hyperviscosity syndrome have also been ascribed to play a role in the development of AVN.1 The role of intravascular coagulation is supported by the fact that the Factor V Leiden gene, a risk factor for coagulation, is overrepresented in patients with AVN when compared with controls.22

There is limited information regarding the role of calcineurin inhibitors (CSA and FK506) and MMF in the development of AVN after HCT. Although the association between calcineurin inhibitors and AVN has been studied by others,9, 16, 23–25 some studies have implicated both CSA and FK506 as risk factors,25 while others only CSA.24, 26 However, research has shown that both CSA and FK506 are thrombogenic in patients with hematologic malignancies, an observation which supports the association between exposure to these agents and development of AVN.27–29 Furthermore, prior studies have also demonstrated an additive effect with exposure to CSA and FK506 for both the development of hyperlipidemia30 and thrombotic microangiopathy.31 This additive effect may be a basis for the observations of the current study that risk of AVN was increased in patients exposed to prednisone, CSA, FK506 and MMF, with the risk increasing with the number of agents used.

Chronic GvHD has been reported as a risk factor for the development of AVN. However, because of the strong correlation between the use of systemic prednisone and the presence of chronic GvHD, it is sometimes difficult to attribute the risk of AVN to chronic GvHD alone. There is emerging evidence that indicates that chronic GvHD may play an independent pathogenetic role in the development of AVN, due to the increased risk of microangiopathy.32, 33 As described above, immunosuppressive agents such as CSA and FK506 have also been reported to cause vascular damage,33, 34 thus setting the stage for an increased risk of AVN associated with both factors through the same mechanism. Our results support the hypothesis that chronic GvHD and immunosuppressive agents are independent risk factors for the development of AVN.

The results of previous studies have been inconsistent when describing the gender-related differences in risk of AVN. Some studies have reported an increased risk among males,11 while others have demonstrated an increased risk in females,10 and some have failed to demonstrate a gender preference.8, 15 Our study demonstrated an increased risk of AVN in males, primarily in allogeneic HCT recipients, which could potentially be explained by differential metabolism of calcineurin inhibitors by gender – an area that needs further exploration.

This study describes the low magnitude of risk of AVN after autologous HCT. The cumulative incidence of AVN in autologous HCT recipients approached 2.5% at 5 years. The large majority of events were diagnosed by five years from HCT. No clinical or demographic risk factors were identified.

The current study has some limitations that are discussed here. AVN patients were diagnosed after they developed clinical signs and symptoms, and not as a result of routine radiological screening. Our results therefore, may not be generalizable to those diagnosed through routine radiological screening. Furthermore, it would have been ideal to have the dose and duration of the immunosuppressive agents in order to understand more completely the individual contributions of the immunosuppressive agents in the development of AVN. However, it is logistically impossible to calculate the dose or duration of the individual immunosuppressive agents used for the long-term management of chronic GVHD in this population, and this study therefore, could not explore a detailed dose-response association. The observed increased risk among those transplanted after 1986 is probably a reflection of the changing transplantation practices, in particular increasing number of unrelated donor HCTs, and use of a wider variety of immunosuppressive agents for the management of chronic GvHD.

The strengths of this study include a comprehensive and complete assessment of a large population of HCT recipients, including autologous HCT recipients, and the ability to examine the role of immunosuppressive agents such as calcineurin inhibitors, MMF, and prednisone, independent of chronic GvHD in the development of AVN after allogeneic HCT. AVN is a debilitating condition, frequently requiring surgical interventions to ensure relief from pain, as evidenced by the fact that 30% of the patients underwent surgery by 1 year from diagnosis, and about 50% required surgery by 5 years. Future studies should examine the pathogenetic mechanism underlying AVN, thus setting the stage for targeted interventions to prevent this chronic debilitating condition.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH R01 CA078938 (S.B.), P01 CA30206 (S.J.F.), Lymphoma/Leukemia Society Scholar Award for Clinical Research 2191-02 (S.B.)

References

- 1.Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:94–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang CC, Greenspan A, Gershwin ME. Osteonecrosis: current perspectives on pathogenesis treatment. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23:47–69. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(05)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerachian MA, Harvey EJ, Cournoyer D, Chow TYK, Seguin C. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: vascular hypotheses. Endothelium. 2006;13:237–244. doi: 10.1080/10623320600904211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lafforgue P. Pathophysiology and natural history of avascular necrosis of bone. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger B, Beier R, Zimmermann M, Beck JD, Reiter A, Schrappe M. Osteonecrosis: a treatment related toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)--experiences from trial ALL-BFM 95. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:220–225. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattano LA, Jr, Sather HN, Trigg ME, Nachman JB. Osteonecrosis as a complication of treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: a report from the Children's Cancer. Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3262–3272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss AJ, Su JT, Dalton VM, Gelber RD, Sallan SE, Silverman LB. Bony morbidity in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:3066–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright H, Haake R, Weisdorf D. Avascular necrosis of bone: a common serious complication of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am. J. Med. 1990;89:733–738. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink JC, Leisenring WM, Sullivan KM, Sherrard DJ, Weiss NS. Avascular necrosis following bone marrow transplantation: a case-control study. Bone. 1998;22:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulte CM, Beelen DW. Avascular osteonecrosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: diagnosis and gender matter. Transplantation. 2004;78:1055–1063. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000138026.40907.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socie G, Selimi F, Sedel L, et al. Avascular necrosis of bone after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: clinical findings, incidence risk factors. Br. J. Haematol. 1994;86:624–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Socie G, Cahn JY, Carmelo J, et al. Avascular necrosis of bone after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: analysis of risk factors for 4388 patients by the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle (SFGM) Br. J. Haematol. 1997;97:865–870. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1262940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Socie G, Loiseau P, Tamouza R, et al. Both genetic and clinical factors predict the development of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:699–706. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tauchmanova L, De Rosa G, Serio B, et al. Avascular necrosis in long-term survivors after allogeneic or autologous stem cell transplantation: a single center experience and a review. Cancer. 2003;97:2453–2461. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torii Y, Hasegawa Y, Kubo T, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin. Orthop. 2001:124–132. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koc S, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, et al. Therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a randomized trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone versus prednisone alone. Blood. 2002;100:48–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators Stat. Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox D. Regression models and life tables. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. 1972;B:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruess RL. Cortisone-induced avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1977;59:308–317. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B3.893509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fryer JP, Granger DK, Leventhal JR, Gillingham K, Najarian JS, Matas AJ. Steroid-related complications in the cyclosporine era. Clin. Transplant. 1994;8:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang S, Chan TM, Lui SL, Li FK, Lo WK, Lai KN. Risk factors for avascular bone necrosis after renal transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2000;32:1873–1875. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zalavras CG, Vartholomatos G, Dokou E, Malizos KN. Genetic background of osteonecrosis: associated with thrombophilic mutations? Clin. Orthop. 2004:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goffin E, Devogelaer JP. Bone disorders after organ transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2005;37:2832–2833. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakai T, Sugano N, Kokado Y, Takahara S, Ohzono K, Yoshikawa H. Tacrolimus may be associated with lower osteonecrosis rates after renal transplantation. Clin. Orthop. 2003:163–170. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093908.26658.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern JM, Sullivan KM, Ott SM, et al. Bone density loss after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a prospective study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:257–264. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11400947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbott KC, Koff J, Bohen EM, et al. Maintenance immunosuppression use and the associated risk of avascular necrosis after kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2005;79:330–336. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000149894.95435.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gopal AK, Thorning DR, Back AL. Fatal outcome due to cyclosporine neurotoxicity with associated pathological findings. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:191–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jumani A, Hala K, Tahir S, et al. Causes of acute thrombotic microangiopathy in patients receiving kidney transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2004;2:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadir Y, Hoffman R, Brenner B. Drug-related thrombosis in hematologic malignancies. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2004;8:E4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathis AS, Dave N, Knipp GT, Friedman GS. Drug-related dyslipidemia after renal transplantation. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 2004;61:565–585. quiz 586–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortin MC, Raymond MA, Madore F, et al. Increased risk of thrombotic microangiopathy in patients receiving a cyclosporin-sirolimus combination. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:946–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holler E, Kolb HJ, Hiller E, et al. Microangiopathy in patients on cyclosporine prophylaxis who developed acute graft-versus-host disease after HLA-identical bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;73:2018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettitt AR, Clark RE. Thrombotic microangiopathy following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizzolato GP, Sztajzel R, Burkhardt K, Megret M, Borisch B. Cerebral vasculitis during FK 506 treatment in a liver transplant patient. Neurology. 1998;50:1154–1157. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]