Abstract

Objective:

The goal of the present study was to examine prospectively two interrelated processes simultaneously: (1) the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies and (2) the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use.

Method:

Participants were from an ongoing longitudinal study of children of alcoholics. Path analyses were used to test paternal transmission (n = 325 fathers and their offspring) and maternal transmission (n = 415 mothers and their offspring).

Results:

Results indicated that boys' alcohol expectancies were influenced by their fathers' alcoholism diagnosis rather than by their fathers' beliefs about the effects of alcohol. There was no evidence of the transmission of beliefs for girls from mothers or fathers, or for boys from mothers. Furthermore, among boys only, alcohol expectancies partially mediated the effect of paternal alcoholism on drinking during young adulthood.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that fathers' alcohol-use behavior is more influential in boys' alcohol expectancy development than are fathers' expectancies and that alcohol expectancies during emerging adulthood may be one mechanism underlying the intergenerational transmission of drinking among males.

Alcohol expectancies, or beliefs that individuals have concerning the positive and negative effects of alcohol, have been repeatedly associated both concurrently and prospectively with drinking among adolescents and adults (Brown et al., 1985; Jones et al., 2001; Mann et al., 1987; Sher et al., 1996), as well as with high-risk or problem drinking (Mann et al., 1987; Smith and Goldman, 1994). The development of alcohol expectancies is complex and the result of both genetic and environmental factors, as well as a function of an individual's own history of alcohol-use behavior (Agrawal et al., 2007; Slutske et al., 2002; Vernon et al., 1996).

According to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), children learn in part by imitating and modeling their parents' behaviors. For example, Brown and colleagues (1999) found that exposure to an alcohol-abusing family member, over and above a family history of alcoholism, predicted stronger positive alcohol expectancies. Thus, beliefs about alcohol effects may be formed, at least partially, as a result of exposure to information from parent models, as well as peer, media, and neighborhood influences (Chung et al., 2008; Dunn and Yniguez, 1999).

During adolescence and young adulthood, the development of alcohol expectancies becomes more complex as individuals continue to be exposed to alcohol-using models but also begin drinking and thus experience alcohol effects firsthand. The pharmacological vulnerability model (Schuckit, 1980; Sher, 1991) suggests that individuals experience differing effects from drinking alcohol that put them at differentiated risk for the development of alcohol-use disorders. For example, male children of alcoholics (COAs) have been shown to experience low levels of subjective intoxication after moderate alcohol consumption, compared with their non-COA peers (Schuckit, 1980). This low subjective response to alcohol predicts alcohol dependence (Schuckit and Smith, 1996). COAs may also experience greater stress-response dampening benefits from alcohol than do non-COAs (Finn et al., 1990). Importantly, these individual differences appear to be genetically mediated (Schuckit et al., 2001).

If COAs experience alcohol effects differently than do non-COAs and if they are exposed to parent models of alcohol effects, then both of these influences may shape their alcohol expectancies. Indeed, research suggests that COAs hold stronger beliefs about alcohol outcomes than do non-COAs (e.g., Brown et al., 1987; Sher et al., 1991). Moreover, positive alcohol expectancies have been implicated as a mechanism by which alcoholism is transmitted across generations. In particular, this mechanism has been supported among a sample of college students (Sher et al., 1996) but not younger adolescents (Colder et al., 1997). More research is needed to understand the role of expectancies in the transmission of alcoholism across generations.

Although previous research has clearly demonstrated that parents' drinking behavior influences children's alcohol expectancies, the impact of parents' own alcohol expectancies on children's alcohol expectancy development has yet to be adequately examined. The intergenerational transmission of beliefs may expand our understanding of the way in which parents transmit alcohol risk to children. Moreover, because parents' expectancies are potentially malleable (Lau-Barraco and Dunn, 2008), they could be important targets for preventive intervention programs. Therefore, an examination of the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies has potential importance for both theory and preventive intervention.

Research on the intergenerational transmission of other beliefs, values, and attitudes has provided evidence of continuity between parents and children (e.g., O'Bryan et al., 2004; Pinquart and Silbereisen, 2004). Moreover, within substance-use research, there is also some indication of the parent–child correlation in substance-related beliefs (Johnson et al., 1990; Shen et al., 2001). Johnson and colleagues (1990) found significant correlations between parent and child that varied by the gender of both parent and child, from r = .71 (between mothers and sons) to r = .37 (between mothers and daughters). Shen and colleagues (2001) also found evidence of the transmission of beliefs across generations; however, similarity varied by familial alcoholism risk. Finally, in a study of implicit and explicit attitudes toward smoking, above and beyond parents' actual smoking behavior, mothers' implicit attitudes about smoking were significantly related to their children's implicit attitudes, indicating that even when parents' overt behaviors are taken into account, parental attitudes remained influential (Sherman et al., 2009).

Although these studies provide an important foundation for our understanding of parent–child continuity in beliefs about substances, more questions remain. In particular, these two interrelated processes (the transmission of alcohol expectancies and alcohol use) have yet to be examined in the same study. Therefore, the primary aim of the current study was to test simultaneously two interrelated processes: (1) the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies and (2) the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use. An exploration of these processes together allows for a test of the influence of parental expectancies and parental alcoholism on offspring expectancies, as well as an examination of alcohol expectancies as one possible mechanism by which alcoholism risk is transmitted across generations. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies prospectively and to examine this process in association with the process of alcohol-use transmission.

Method

Participants

Participants were from a longitudinal study of the intergenerational transmission of alcohol disorders (Chassin et al., 1991). A complete description of sample recruitment and representativeness is reported elsewhere (Chassin et al., 1992). To date, fives waves of data have been collected from three generations of individuals. Data on 454 adolescents (meanage [SD] = 13.2 [1.44]; range: 10.5–15.5) and their parents were collected at Wave 1; 246 had at least one biological alcoholic parent who was also a custodial parent (COAs), and 208 were demographically matched adolescents with no biological or custodial alcoholic parents (controls). There were three annual assessments (Waves 1–3) of the adolescents and their parents and two long-term follow-ups 5 years apart (Waves 4 and 5). Therefore, adolescents and their parents were interviewed five times (Waves 1–5) between ages 11 and 30 years. The current study used data from Waves 1, 3, 4, and 5. Sample retention has averaged more than 90% since the advent of the study.

To maximize sample size, models were tested separately for maternal and paternal transmission of alcohol expectancies. This allowed for the inclusion of single parent families and families in which only one parent was interviewed. We included only biological parents because information was available on their lifetime alcohol diagnosis. Because the larger sample from which these data were drawn over-sampled for two biological parent families, this criterion did not drastically reduce the sample. At Wave 1, 95.0% of interviewed mothers and 94.4% of interviewed fathers were the biological parents of the interviewed children.

Participants were included in the paternal transmission model if the father who was interviewed at Wave 3 (the wave in which parental alcohol expectancies were measured) was the biological father (n = 325 of the total 350 fathers interviewed at Wave 3). Participants were included in the maternal model if the interviewed mother at Wave 3 was the biological mother (n = 415 of the total 433 mothers interviewed at Wave 3).

The mean age of adolescents at Wave 3 was 14.66 (1.47) years, 20.37 (1.36) years at Wave 4, and 25.68 (1.64) years at Wave 5. Given these ages, we refer to Wave 4 as “emerging adulthood” and Wave 5 as “young adulthood.” Approximately half (47.1%) of the participants were female and had at least one alcoholic parent (52.7%). The majority of fathers and mothers were white (77.4% and 80.7%, respectively) and had some post-high school education but less than a college degree. The mean age of mothers at Wave 3 was 41.00 (5.40) years, and the mean age of fathers was 40.02 (5.87) years. Approximately half (50.5%) of the fathers included in the paternal transmission model and 12.0% of the mothers included in the maternal transmission model met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980), criteria for lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence at Wave 1.

Differences between adolescents included in the paternal transmission model (n = 325) and those excluded (n = 129) were tested on all variables of interest (t tests). Included adolescents were less likely to have an alcoholic mother (t = 6.19, 452 df, p < .001) but not less likely to have an alcoholic father. Included adolescents were also less likely to have a highly educated father (t = 2.36, 347 df, p < .05). There were no differences between those included and excluded in gender, drinking at any of the three waves, alcohol expectancies at Waves 3 and 4, fathers' alcoholism, or fathers' expectancies.

Differences between adolescents included (n = 415) and excluded (n = 39) from the maternal model were also examined. Included adolescents drank less at Wave 4 (t = 2.31, 405 df, p < .05) and were less likely to have a white mother (t = −3.37, 36.93 df, p < .05) and an alcoholic father (t = 4.32, 48.30 df, p < .001). However, there were no differences between included and excluded adolescents in gender, drinking at Waves 3 and 5, alcohol expectancies at Waves 3 and 4, mothers' alcoholism, parents' educational attainment, or expectancies. Nevertheless, the differences that were found suggest caution in generalization.

Procedure

In this institutional review board–approved protocol, data were collected with computer-assisted interviews either at families' homes or at the university. To minimize contamination, family members were interviewed individually on the same occasion, by different interviewers when possible. When a family moved out of state, an interviewer from a nearby university administered a shortened version, and the diagnostic interview was done by telephone. If no nearby interviewer was available, the entire interview was done by telephone. Interviewers were unaware of the family's group membership. To encourage honest responding, we reinforced confidentiality with a Department of Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality. To maximize privacy, participants could enter their responses on the keyboard rather than verbally.

Measures

Parental alcohol-use disorder.

Parents' lifetime alcoholism diagnosis was defined as lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence using DSM-III criteria and was obtained at Wave 1 from a computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III (Robins et al., 1981). For noninterviewed parents, alcoholism diagnoses were based on Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (Endicott et al., 1975), using information from their spouse's report. Parental alcoholism was considered a dichotomous variable (0 = nonalcoholic, 1 = alcoholic).

Alcohol expectancies.

Participants and their parents self-reported their positive alcohol expectancies using items from Mann and colleagues' (1987) adaptation of the Alcohol Expectancies Questionnaire (Christiansen et al., 1982). Parents reported on their alcohol expectancies at Wave 3, and participants reported on their alcohol expectancies at Waves 3 and 4. The response scale for all items ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

There were 10 positive expectancy items, including expectancies for personal power (e.g., “Drinking alcohol makes me feel more powerful than others”), tension reduction (e.g., “Drinking alcohol helps me when I'm tense and nervous”), and social enhancement (e.g., “Drinking alcohol makes parties more fun”). Higher scores indicated stronger beliefs about the benefits of drinking. Cronbach's alphas ranged from .90 to .94 across reporters and waves.

Alcohol consumption.

Participants self-reported their past-year quantity and frequency of drinking beer/wine/wine coolers at Waves 3, 4, and 5, and quantity was multiplied by frequency. Because modeling techniques are sensitive to nonnormality, a log transformation was used to reduce skewness and kurtosis and then multiplied by 10 to facilitate interpretation. Forty-five percent of adolescents had at least one drink in the past year at Wave 3. This increased to 79.7% at emerging adulthood and 81.4% at young adulthood.

Results

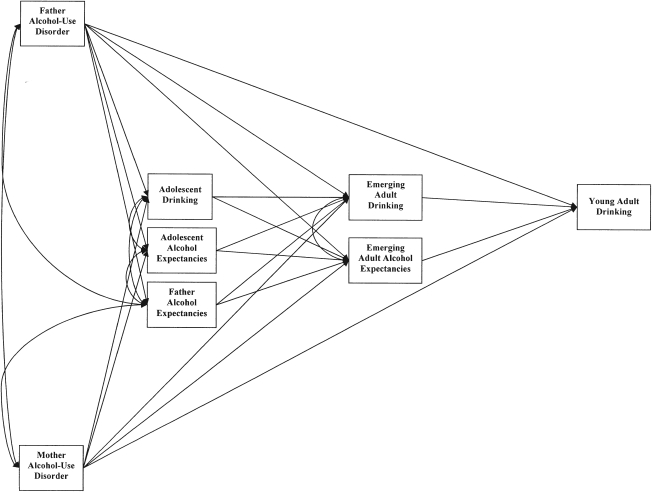

The two models were tested with longitudinal path analysis using MPlus version 4.21 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2006) and full-information maximum likelihood for missing data. All continuous study variables were within the acceptable range of skew and kurtosis. The hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1. Parents' educational attainment, ethnicity, and offspring age were tested as potential covariates but were not found to be predictive of the outcome variable. Therefore, they were trimmed from the models. Moreover, the interaction of parents' expectancies and parents' alcoholism diagnosis did not predict offspring alcohol expectancies in either the father or mother model and was therefore also trimmed from the final models. Finally, the interaction of parents' alcoholism diagnosis and adolescents' expectancies did not predict drinking and was therefore also trimmed from the final models.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of the intergenerational transmission of positive alcohol expectancies: Father–son model

Zero-order correlations are presented in Table 1. Results indicated that parents' alcohol expectancies were not significantly related to offspring alcohol expectancies contemporaneously or prospectively. However, for boys, fathers' alcoholism was related to expectancies during emerging adulthood (r father model = .33; r mother model = .30) but not during adolescence. For girls, fathers' alcoholism was unrelated to expectancies at either time point. Mothers' alcoholism was unrelated to offspring expectancies during adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among study variables for each model

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

| Father model (n = 325) | ||||||||

| 1. Father alcoholism | — | .06 | .15 | .28* | .23* | .33* | .02 | −.06 |

| 2. Mother alcoholism | −.01 | — | −.06 | .06 | .26* | −.14 | −.04 | −.08 |

| 3. Adolescent drinking | .25* | .02 | — | .42* | .23* | .10 | .24* | .03 |

| 4. EA drinking | .25* | .10 | .48* | — | .50* | −.01 | −.08 | .14 |

| 5. YA drinking | .23* | .12 | .26* | .55* | — | .13 | −.01 | .02 |

| 6. Father expectancies | .18* | .15* | −.01 | .14 | .17* | — | .07 | −.02 |

| 7. Adolescent expectancies | .03 | .11 | .26* | .14 | −.01 | −.01 | — | .29* |

| 8. EA expectancies | .33* | .01 | .14 | .26* | .31* | .14 | .22* | — |

| Mother model (n = 415) | ||||||||

| 1. Father alcoholism | — | .08 | .17* | .25* | .22* | .08 | −.02 | −.05 |

| 2. Mother alcoholism | −.05 | — | .10 | .09 | .17* | .13 | .01 | .02 |

| 3. Adolescent drinking | .27* | .12 | — | .37* | .29* | .03 | .32* | .05 |

| 4. EA drinking | .19* | −.03 | .40* | — | .45* | −.01 | .01 | .18* |

| 5. YA drinking | .24* | −.02 | .21* | .57* | — | −.04 | .10 | .04 |

| 6. Mother expectancies | −.02 | .14* | .04 | .04 | .06 | — | −.01 | .09 |

| 7. Adolescent expectancies | .12 | .02 | .24* | .11 | .01 | −.06 | — | .33* |

| 8. EA expectancies | .30* | .08 | .15* | .16* | .21* | .02 | .20* | — |

Notes: Correlations for male offspring are presented on the bottom half of the diagonal, and correlations for the female offspring are presented on the top half of the diagonal. EA = emerging adult; YA = young adult.

p < .05.

Paternal intergenerational transmission

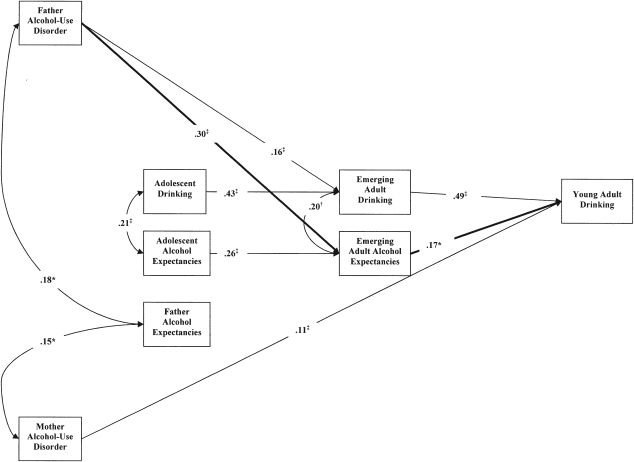

We first tested an overall model for the intergenerational transmission of positive beliefs from father to child, which was not a good fit to the data (χ2 = 46.43, 29 df, p = .02, comparative fix index [CFI] = .94, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .06, standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = .06). However, there was evidence of moderation by offspring gender such that allowing paths to vary by gender provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 32.33, 22 df, p = .07, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05), significantly better than the overall model (Δχ2 difference = 14.10, 7 df, p < .05). All standardized path coefficients are presented in Table 2. Results did not support the transmission of alcohol expectancies from fathers to boys or girls. Rather, during emerging adulthood, boys' beliefs about alcohol were predicted from fathers' alcoholism (β = .30, p < .001), such that having an alcoholic father predicted stronger positive alcohol expectancies. This path was nonsignificant for girls. Moreover, strong positive expectancies during emerging adulthood predicted greater young adult drinking among boys only (β = .17, p < .05). Consistent with previous literature, fathers' alcoholism significantly predicted emerging adult drinking for both genders (boys: β = .17, p < .001; girls: β = .21, p < .001). Fathers' expectancies, however, were unrelated to offspring emerging adult drinking. Moreover, fathers' alcoholism was unrelated to adolescent drinking and expectancies, as well as young adult drinking. As expected, there was significant stability in expectancies from adolescence to emerging adulthood (boys: β = .26, p < .001; girls: β = .22, p < .001) and significant stability in drinking from adolescence to emerging adulthood (boys: β = .44, p < .001; girls: β = .45, p < .001) and from emerging adulthood to young adulthood (boys: β = .49, p < .001; girls: P = .45, p < .001). Finally, the effects of mothers' alcoholism were nonsignificant, except for the prediction of young adult drinking (boys: β = .11, p < .001; girls: β = .18, p < .001). Significant paths for boys are presented in Figure 2. Results for the girls are not presented in the figure because of the lack of significant paths.

Table 2.

Standardized path coefficient (β) estimates for father model

| From: | Path to: | Girls estimate | Boys estimate |

| Father AUD | Adolescent drinking | .01 | .01 |

| Adolescent expectancies | −.02 | −.02 | |

| EA drinking | .21‡ | .17‡ | |

| EA expectancies | −.07 | .30‡ | |

| YA drinking | .08 | .07 | |

| Mother AUD | Adolescent drinking | −.03 | −.02 |

| Adolescent expectancies | .04 | .10 | |

| EA drinking | .10 | .06 | |

| EA expectancies | −.07 | −.04 | |

| YA drinking | .18‡ | .11‡ | |

| Father expectancies | EA drinking | −.10 | .10 |

| EA expectancies | −.03 | .09 | |

| Adolescent drinking | EA drinking | .45‡ | .44‡ |

| EA expectancies | −.01 | −.01 | |

| Adolescent expectancies | EA drinking | −.21† | .04 |

| EA expectancies | .22‡ | .26‡ | |

| EA drinking | YA drinking | .45‡ | .49‡ |

| EA expectancies | YA drinking | −.02 | .17* |

Notes: AUD = alcohol-use disorder; EA = emerging adult; YA = young adult.

p < .05;

p < 01;

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Intergenerational transmission of positive alcohol expectancies: Father–son model. Only significant paths are shown. Results are presented for boys only. The mediation path of interest is bolded. Standardized path coefficients are shown.

*p < .05; † p < 01; ‡ p < .001.

To test whether offspring alcohol expectancies mediated the relation between father alcoholism and subsequent drinking, 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence limits were used (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Emerging adult alcohol expectancies significantly mediated the effect of fathers' alcoholism diagnosis on later drinking for boys (upper confidence limit [UCL] = .114; lower confidence limit [LCL] = .010) but not girls (UCL = .025, LCL = −.008). Additionally, emerging adult drinking significantly mediated the relation between fathers' alcoholism diagnosis and young adult drinking for both boys (UCL = .145, LCL = .035) and girls (UCL = .145, LCL = .035). None of these mediated effects were seen during adolescence. Specifically, adolescent expectancies did not mediate the relation between fathers' alcoholism diagnosis and emerging adult drinking for boys (UCL = .008, LCL = −.028) or girls (UCL = .045, LCL = −.022). Adolescent drinking also did not mediate this relation (boys: UCL = .010, LCL = −.003; girls: UCL = .010, LCL = −.003). None of the other mediation chains were significant for either gender.

Maternal intergenerational transmission

We next tested the maternal transmission model, and it fit the data well (χ2 = 7.43, 6 df, p = .28, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .02). There was no evidence of moderation by offspring gender (χ2 = 45.62, 24 df, p = .005, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .05), because the original model was a significantly better fit to the data than the gender-moderated model (Δχ2 difference = 38.19, 18 df, p < .01). Results did not support intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies from mother to child. Specifically, neither maternal alcohol expectancies nor maternal alcoholism diagnosis predicted adolescent or emerging adult alcohol expectancies. The only significant paths in the maternal model were stability paths (offspring alcohol expectancies stability [β = .22, p < .001] and alcohol-use stability over time [adolescent to emerging adulthood: β = .40, p < .001; emerging adulthood to young adulthood: β = .50, p < .001]) and effects of paternal alcoholism on offspring drinking at all three waves (βadolescent = .21, p < .001; βemerging adulthood = .14, p < .01; βyoung adulthood = .11, p < .02). Furthermore, there was no evidence for emerging adult expectancies as a mediator in the link between maternal alcoholism and young adult drinking (UCL = .017, LCL = −.010), nor was there evidence for emerging adult drinking as a mediator in this link (UCL = .046, LCL = −.126). Adolescent drinking mediated the relation between maternal alcoholism and emerging adulthood drinking (UCL = .136, LCL = .001); however, adolescent expectancies did not (UCL = .008, LCL = −.010). None of the other meditational chains were significant. These results are not pictured in a figure because of the lack of significant effects.

Because drinking experience could moderate these effects, in a separate model we tested whether the effect of either mothers' or fathers' alcoholism diagnosis on adolescents' expectancies and later drinking varied by whether adolescents' had initiated drinking. We found no evidence of moderation by initiation into drinking.

Discussion

The present study examined the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies and alcohol use longitudinally using a high-risk sample. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test the transmission of beliefs about drinking across generations prospectively and to simultaneously examine the two potentially interrelated processes of alcohol-use and expectancy transmission.

Results did not support the intergenerational transmission of positive alcohol expectancies. Although there is some evidence from previous studies suggesting correlations between parent and child beliefs about substances (Johnson et al., 1990; Shen et al., 2001; Sherman et al., 2009), our results did not support either contemporaneous or prospective transmission. This finding held true regardless of the child's initiation into drinking. Moreover, contrary to Shen and colleagues (2001), the effect of parental expectancies on offspring expectancies did not depend on parental alcoholism. Differences in measurement may explain the seemingly inconsistent findings. Specifically, the current study used a measure of positive alcohol expectancies derived from the Alcohol Expectancies Questionnaire (Christiansen et al., 1982), which included expectancy domains such as personal power, tension reduction, and social enhancement, whereas other studies have measured “subjective responses to alcohol,” which included both positive and negative expectancies (Johnson et al., 1990) or individual subscales from the Alcohol Expectancies Questionnaire (Shen et al., 2001).

Although the present study did not support the intergenerational transmission of expectancies, results demonstrated the importance of parental alcoholism and gender in alcohol expectancy development. Specifically, for boys, positive alcohol expectancies were shaped by their fathers' alcoholism diagnosis and not by their fathers' own beliefs about drinking, such that sons of alcoholic fathers held stronger positive alcohol expectancies during emerging adulthood. Thus, boys were more strongly influenced by their fathers' behavior than by their fathers' beliefs. The influence of a family history of alcoholism on alcohol expectancies has been documented previously (i.e., Brown et al., 1987). The present study replicated and extended this research by indicating that the effect may be male specific.

Paternal alcoholism effects on sons' alcohol expectancies may reflect either social learning processes or individual differences in alcohol effects, or both. Fathers' behavioral demonstration of alcohol effects may be more salient to the development of boys' alcohol expectancies, because they are easier for boys to observe than are fathers' alcohol expectancies. Additionally, fathers' alcoholism may be more influential in shaping boys' alcohol expectancies than fathers' own alcohol expectancies, because paternal alcoholism risk may be at least partially mediated by individual differences in alcohol effects. For example, sons of male alcoholics (SOMAs) show lower cardiovascular reactions to stress after consuming alcohol than do non-SOMAs. Also, SOMAs experience more physiologically pleasurable effects from drinking than do non-SOMAs (Pihl et al., 1990). If sons of alcoholic fathers experience greater pharmacological benefits from drinking, then these experiences likely shape their alcohol expectancies. Although these data are consistent with our male-specific results, other studies have documented alcohol effects differences between COAs and non-COAs that were not specific to boys (Levenson et al., 1987).

The current study also examined the intergenerational transmission of expectancies in conjunction with the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use. Consistent with Sher and colleagues (1996), our results supported positive alcohol expectancies as a mechanism by which parental alcoholism influences drinking in young adulthood, albeit, in our data, only between fathers and sons. Moreover, this mediated effect was found (consistent with Sher et al., 1996) during emerging adulthood but not during adolescence.

Why might this mediated process be detected in emerging adulthood but not earlier in development? It is possible that this is a developmentally specific phenomenon related to developmental shifts in drinking and alcohol expectancies. Emerging adulthood is a developmental period at greatest risk for heavy drinking and the onset of alcohol-use disorder (Brown et al., 2008) and, as such, may represent a period of sufficient exposure to alcohol effects to reflect familial risk and then influence expectancies. Although a dichotomous variable of abstinence of experience did not significantly moderate the relations between parental alcoholism and alcohol expectancies in our analyses, it may be that, as individuals experience repeated effects of alcohol likely to occur in emerging adulthood, the effects of paternal alcoholism become more salient. More work is needed to clarify the potential role of development and drinking experience in this process.

Interestingly, neither parents' expectancies nor alcoholism diagnoses were predictive of emerging adult expectancies among girls. Moreover, mothers' alcoholism diagnosis did not have the same effect on boys' alcohol expectancies as did fathers' alcoholism diagnosis. Our male-specific findings may reflect a correlated process of intergenerational transmission of behavioral undercontrol or externalizing behaviors, which have been associated both with differential effects of alcohol (Brunelle et al., 2004) and drinking (Iacono et al., 2008). Iacono and colleagues (2008) suggest that this process exists for both men and women but is more detectable in men because of their higher average levels of this undercontrolled/externalizing style and drinking (Iacono et al., 2008). Moreover, because males show more early-onset drinking than do females (Brown et al., 2008), externalizing pathways may not be observed in women until later stages of development. Additionally, the lack of effects from mothers may be the result of statistical power, because only 12% of mothers were alcoholic. Future research, which uses a larger sample of alcoholic mothers, is necessary for a more complete understanding of the role of gender in alcohol expectancy development.

Although this study addressed important gaps in the literature on the development of alcohol expectancies, it is important to recognize its limitations. First, we are unable to disentangle genetic and environmental influences or their interaction. Second, we cannot determine the precise extent of differing exposure to a drinking parent at different ages. Finally, the low base rate of maternal alcoholism may have made it difficult to detect maternal alcoholism effects. More work is needed to understand maternal alcoholism effects, as well as alcohol expectancy development in girls.

In summary, the current study was the first to prospectively test the intergenerational transmission of alcohol expectancies and alcohol use simultaneously. There was no support for the direct transmission of parental alcohol expectancies to offspring emerging adult expectancies. Instead among boys, fathers' alcoholism influenced the development of emerging adult beliefs about alcohol effects, such that having an alcoholic father predicted stronger beliefs about the benefits of drinking. These results suggest that paternal alcohol behavior is more influential in the development of boys' alcohol expectancies than are paternal alcohol expectancies. Furthermore, positive alcohol expectancies during emerging adulthood were identified as a mechanism by which paternal alcoholism transmits risk for later alcohol use to male offspring.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant AA016213.

References

- Agrawal A, Dick DM, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Cooper ML, Sher KJ, Heath AC. Drinking expectancies and motives: A genetic study of young adult women. Addiction. 2007;103:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Creamer VA, Stetson BA. Adolescent alcohol expectancies in relation to personal and parental drinking patterns. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1987;96:117–121. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Goldman MS, Christiansen BA. Do alcohol expectancies mediate drinking patterns of adults? J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1985;53:512–519. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KC, Lowman C, Murphy S. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement):S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tate SR, Vik PW, Haas AL, Aarons GA. Modeling of alcohol use mediates the effect of family history of alcoholism on adolescent alcohol expectancies. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:20–27. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle C, Assaad J-M, Barrett SP, Ávila C, Conrod PJ, Tremblay RE, Pihl RO. Heightened heart rate response to alcohol intoxication is associated with a reward-seeking personality profile. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:394–401. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117859.23567.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Barrera M, Jr, Bech K, Kossak-Fuller J. Recruiting a community sample of adolescent children of alcoholics: A comparison of three subject sources. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1992;53:316–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991;100:449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen BA, Goldman MS, Inn A. Development of alcohol-related expectancies in adolescents: Separating pharmacological from social-learning influences. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1982;50:336–344. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Hipwell A, Loeber R, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Ethnic differences in positive alcohol expectancies during childhood: The Pittsburgh Girls Study. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2008;32:966–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L, Stice EM, Curran PJ. Alcohol expectancies as potential mediators of parent alcoholism effects on the development of adolescent heavy drinking. J. Res. Adolesc. 1997;74:349–374. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Yniguez RM. Experimental demonstration of the influence of alcohol advertising on the activation of alcohol expectancies in memory among fourth- and fifth-grade children. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:473–483. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Andreasen NC, Spitzer RL. Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York Psychiatric Institute; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Zeitouni NC, Pihl RO. Effects of alcohol on psychophysiological hyperreactivity to nonaversive and aversive stimuli in men at high risk for alcoholism. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1990;99:79–85. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Nagoshi CT, Danko GP, Honbo KAM, Chau LL. Familial transmission of alcohol use norms and expectancies and reported alcohol use. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1990;14:216–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Dunn ME. Evaluation of a single-session expectancy challenge intervention to reduce alcohol use among college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008;22:168–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Oyama ON, Meek PS. Greater reinforcement from alcohol for those at risk: Parental risk, personality risk, and gender. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1987;96:242–253. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann ML, Chassin L, Sher KJ. Alcohol expectancies and the risk for alcoholism. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1987;55:411–417. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus, Version 4.1. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- O'Bryan M, Fishbein HD, Ritchey PN. Intergenerational transmission of prejudice, sex role stereotyping, and intolerance. Adolescence. 2004;39:407–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Peterson J, Finn PR. Inherited predisposition to alcoholism: Characteristics of sons of male alcoholics. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1990;99:291–301. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Silberseisen RK. Transmission of values from adolescents to their parents: The role of value content and authoritative parenting. Adolescence. 2004;39:83–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Self-rating of alcohol intoxication by young men with and without family histories of alcoholism. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1980;41:242–249. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, Flury L, Smith TL, Reich T, Bierut L, Goate A, Foroud T. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1996;53:202–210. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen SA, Locke-Wellman J, Hill SY. Adolescent alcohol expectancies in offspring from families at high risk for developing alcoholism. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001;62:763–772. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of Alcoholics: A Critical Appraisal of Theory and Research. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: A latent variable cross-lagged panel study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1996;105:561–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SJ, Chassin L, Presson C, Seo D-C, Macy JT. The intergenerational transmission of implicit and explicit attitudes toward smoking: Predicting adolescent smoking initiation. J. Exp. Social Psychol. 2009;45:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Cronk NJ, Sher KJ, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. Genes, environment, and individual differences in alcohol expectancies among female adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002;16:308–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Goldman MS. Alcohol expectancy theory and the identification of high-risk adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1994;4:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon PA, Lee D, Harris JA, Lang KL. Genetic and environmental contributions to individual differences in alcohol expectancies. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1996;21:183–187. [Google Scholar]