Abstract

We recruited 367 current daily smokers via the Internet and randomized them to rate the causes of an inability to stop smoking, inability to stop problem alcohol use, or inability to lose excess weight in a fictional scenario. Most smokers attributed inability to stop smoking to addiction (88%), habit (88%) and stress (62%). Surprisingly, equal numbers of smokers agreed and disagreed that inability to stop smoking was due to lack of willpower or motivation. Most disagreed that it was due to biological factors, denial, family/upbringing, genetics, mental disease, personality problem, psychological problems, or weakness of character. Many expected correlations among perceived causes were not found; e.g. endorsement of addiction was not inversely related to endorsement of willpower. Most smokers endorsed treatment. Higher ratings of addiction were related to endorsing treatment, and higher ratings of motivation were related to endorsing no need for treatment; however, these relationships were of small magnitude. Ratings of almost all the causes varied across the three problems; e.g. ratings of addiction were greater for smoking than for problem alcohol use. In summary, smokers appear to view the inability to stop smoking as multicausal; however, their views of causes are only weakly related to attitudes towards treatment. Given the several unexpected findings, qualitative research into smokers' conceptualizations about smokers' inability to stop smoking is indicated.

Keywords: alcohol, dependence, expectancy, obesity, smoking cessation, tobacco

1. Introduction

Continued use of a substance despite its causing problems has been attributed to addiction, habit, lack of willpower, etc. Which perceived causes are endorsed varies across drugs, places, subcultures and time periods (Peele, 1989). Such perceived causes may be important because they may influence treatment seeking; e.g., those who more readily endorse addiction as a cause of problems stopping smoking would be expected to more likely seek treatment.

The current study determined a) which perceived causes smokers report for an inability to stop smoking, b) whether these causes are logically related to each other, c) whether the causes predict treatment endorsement and d) whether perceived causes vary across disorders. Several prior studies have empirically examined how the lay public conceptualizes why people smoke and whether this differs from other drug disorders (Cunningham, Sobell, Freedman, & Sobell, 1994; Cunningham, Sobell, & Sobell, 1996; Eiser, Sutton, & Wober, 1977; Weinstein, Slovic, & Gibson, 2004; Fabricius, Nagoshi, & MacKinnon, 1997; Kozlowski et al., 1989; Cunningham, Sobell, & Chow, 1993; Hughes, 2005; Humphreys, Greenbaum, Noke, & Finney, 1996). Although these studies present intriguing results, none focuses specifically on smokers' perceptions of the causes of other smokers' inability to stop smoking. Other studies have focused on why smokers believe they themselves cannot stop smoking (Balmford & Borland, 2008). We focused instead on smokers' perceptions of a modal smoker because oftentimes persons believe they do not conform to the norms for a group they belong to (.e.g. smokers often state that they are at less risk of death from smoking as the modal smoker) (Weinstein et al., 2004).

2. Methods

We recruited smokers using the Zoomerang website (www.zoomerang.com) which has a database of 3 million US consumers who have agreed to complete online surveys in return for points redeemable for services and merchandise. We emailed an invitation to a random subsample of known current smokers that stated “Smokers wanted to complete a brief online survey (5-10 min) about your views of alcohol or cigarette use or obesity in return for Zoomerang points.” The website obtained informed consent and asked the two inclusion criteria of a) over age 24, and b) currently smoking daily. Zoomerang was not able to provide information on response rate nor on how many smokers were excluded. Participants were recruited over 3 days and we stopped recruitment after 367 smokers completed the survey because this would provide over 100 smokers for each of the three surveys and we believed this would provide sufficient accuracy for our first study in this area. After consent, we randomized participants to complete a survey about the causes of inability to stop smoking, a survey on inability to stop problematic alcohol use, or a survey on inability to lose weight when obese

Participants were mostly non-Hispanic Caucasians (89%) who were often married (52%) and usually worked full or part time (62%). Males and females were equally represented (51% males) and many participants (38%) had completed college. Their mean age was 48 (sd = 14). Participants smoked a mean of 19 (10) cigs/day, had a mean Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score of 4.4 (2.2) and 81% smoked within 30 minutes after awakening. Most (65%) had tried to quit smoking for good on several occasions. Despite being recruited from the internet, the sample appeared comparable to smokers in the most recent US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm) and US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH; www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh) population-based samples of current smokers on age, education, gender and cigs/day (Hughes, 2004). The sample also had a similar FTND score (Fagerstrom & Furgerg, 2008) and prevalence of past quit attempts to recent US national surveys (Giovino, 2002). The sample was under-represented in minorities (11% vs. 22% in the NHIS). About half (53%) of participants used alcohol monthly or less; 23% met criteria for current hazardous drinking (i.e. > 14 drinks/wk) and 22% reported binge drinking (consumed ≥ 5 drinks on occasion) monthly. (Murgraff, Parrott, & Bennett, 1999) Few (19%) had tried to stop alcohol for good on several occasions. One-third (33%) were overweight (BMI ≥ 25) and 31% obese (BMI ≥ 30). Almost half (44%) had tried to lose weight on several occasions. These alcohol and weight outcomes are consistent with prior surveys that smokers drink more and weigh less than never or ex-smokers (Fine, Philogene, Gramling, Coups, & Sinha, 2004). Among the above characteristics, the proportion of non-whites and FTND scores differed across the three survey groups; however, when these two variables were used as covariates, the results did not change; thus, we report only unadjusted results.

Although multi-item scales have been developed to measure perceived causes of the inability to change (Humphreys et al., 1996; Luke, Ribisl, Walton, & Davidson, 2002; Schaler, 1995; West & Power, 1995b), none covered all of the causes we wished to examine nor was adaptable to different problems, plus all were lengthy. Thus, we employed single terms that have been used in prior studies of conceptualizations of tobacco and alcohol use and dependence (Table 1). In an informal, qualitative pre-test in a convenience sample of 30 persons with high school but not college degrees, no one reported problems understanding our terms.

Table 1.

Percent Agreement and Mean Ratings for Perceived Causes of the Inability to Stop Smoking, Stop Problematic Alcohol Use or Lose Excessive Weight a

| Scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker (n = 122) |

Alcohol User (n = 122) |

Obese Person (n = 123) |

Differences b | |

| Continued use is due to | ||||

| Addiction | 88% (+1.5*) | 77% (+1.1) | 42% (+0.1) | S>A>O |

| Habit | 88% (+1.4*) | 69% (+0.8) | 54% (+0.4*) | S>A>O |

| Lack of willpower | 39% (-0.1) | 33% (-0.1) | 45% (+0.2) | |

| Disease | 10% (-1.0*) | 28% (-0.2) | 13% (-0.5*) | A>O>S |

| Personality problem | 10% (-0.9*) | 24% (-0.2) | 23% (-0.3*) | A=O>S |

| Weakness of character | 10% (-1.1*) | 16% (-0.5) | 22% (-0.4*) | O=A>S |

| Continued use is due to | ||||

| Stress | 62% (+0.6*) | 38% (+0.1) | 47% (+0.4*) | S>A=O |

| Lack of motivation to quit | 42% (-0.1*) | 47% (+0.1) | 50% (+0.4*) | O>S |

| Family/upbringing | 29% (-0.3*) | 36% (0.0) | 58% (+0.4*) | O>A>S |

| Biological factors | 21% (-0.4*) | 35% (0.0) | 51% (+0.4*) | O>A>S |

| Genetics | 20% (-0.6*) | 40% (0.0) | 59% (+0.5*) | O>A>S |

| Psychological problems | 15% (-0.7*) | 39% (+0.1) | 27% (-0.1*) | A=O>S |

| Denial | 13% (-0.7*) | 36% (+0.1) | 26% (-0.2*) | A>O>S |

| If tries to change, person should | ||||

| Use medication | 56% (+0.6*) | 35% (+0.1) | 30% (-0.1) | S>A=O |

| Use group therapy | 42% (+0.3*) | 60% (+0.6*) | 47% (+0.3*) | |

| Use individual counseling | 34% (+0.2*) | 72% (+0.8*) | 42% (+0.3*) | A>S=O |

| Change on own | 16% (-0.5*) | 19% (-0.6*) | 25% (-0.2*) | O>A |

Percents are endorsed “agree strongly” or “agree somewhat;” ratings are +2 = agree strongly, +1 = agree somewhat, 0 = neither agree nor disagree, -1 = disagree somewhat, -2 = disagree strongly; All SEM ≤ 0.2

A = alcohol use, O = obesity, S = smoking; All differences significant (p < .05, LSD post-hoc tests)

p < .05 for one-sample t-test vs 0.0

We chose alcohol problems and obesity as comparators because a) they have similar features (e.g. urges, impaired control) and are prevalent (Flegal, Caroll, Ogden, & Johnson, 2002; Grant et al., 2004; Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004) and b) how much each is an addiction vs. habit is widely debated (Peele, 1989; Riva et al., 2006; Frenk & Dar, 2000). The surveys described one of three scenarios designed to mimic a common scenario; i.e., a) “a current daily smoker who knows they have a smoking-related illness and has tried to quit on several occasions”), b) “a current heavy drinker with current social or health problems from alcohol use who has tried to stop on several occasions,” and c) “someone whose weight is ≥ 30% of their normal weight (i.e. obese) who has weight-related health problems and who has tried to lose weight on several occasions.” We used scenarios because we were interested, not in smokers' perception of their own smoking, but that of most other smokers. We asked smokers to rate inability to change for each scenario on a 5 point scale whether they agreed or disagreed that the inability to change was due to each of 13 causes; e.g. we asked “This person's continued smoking is probably due to an addiction.” We also asked whether smokers agreed or disagreed that the fictional person should use medications, group therapy, or individual counseling to change or should change on their own.

We focus in this paper on perceived causes of smoking because our sample consisted of smokers. Results for the alcohol and obesity scenarios are presented only in relationship to the smoking results. Although we asked participants about their perceptions not of themselves but of a fictional other person, readers should remember that smokers had more personal experience with attempts to quit smoking than to stop problematic drinking or lose excessive weight.

3. Results

3.1 Endorsements for the Inability to Stop Smoking

Smokers endorsed addiction, habit, and stress as causes of the inability to stop smoking (nb – we use “inability to stop” and “continued smoking” as synonyms) but disagreed that inability to stop was due to a mental disease, personality problem, weakness of character, lack of motivation, family/upbringing, biological factors, genetics, denial or psychological problems (Table 1). Similar proportions of smokers agreed and disagreed that lack of willpower and lack of motivation were reasons for continued use. In a multivariate regression of age, sex, race, education, cigs/day, degree of dependence (FTND), and prior quit attempt on endorsement of addiction or habit, smokers with higher dependence had greater endorsement of addiction (p = .01) and women were more likely to endorse habit (p = .02).

3.2. Correlations Among Perceived Causes

Multiple correlations among causes were found (Table 2). For brevity, we comment only on our a priori expected correlations based on the prior literature (Cunningham et al., 1994; Cunningham et al., 1996; Eiser et al., 1977; Weinstein et al., 2004; Fabricius et al., 1997; Kozlowski et al., 1989; Cunningham et al., 1993; Hughes, 2005; Humphreys et al., 1996). We expected ratings of addiction to be negatively correlated with ratings of habit but they were positively correlated. We expected addiction ratings to be positively correlated with biological or genetic causation ratings, but they were not. We expected addiction ratings to be negatively correlated with endorsement of lack of willpower and motivation but only the former occurred.

Table 2.

Statistically Significant Correlations (r > .18, p< .05) Among Endorsements of Causes of the Inability to Stop Smoking and With Endorsements of Treatments for Smoking Cessationa

| Add | Hab | Will | Dis | Pers | Char | Str | Mot | Fam | Biol | Gen | Psyc | Den | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction | |||||||||||||

| Habit | .55 | ||||||||||||

| Willpower | -.20 | ||||||||||||

| Disease | |||||||||||||

| Personality | -.26 | .37 | .47 | ||||||||||

| Character | .56 | .45 | .58 | ||||||||||

| Stress | |||||||||||||

| Motivation | .56 | .31 | .47 | .29 | |||||||||

| Family | .26 | .20 | .31 | .25 | .39 | .28 | |||||||

| Biology | .21 | .26 | .21 | .44 | |||||||||

| Genetics | .21 | .32 | .46 | .34 | .25 | .54 | .63 | ||||||

| Psych problems | .21 | .35 | .53 | .49 | .33 | .31 | .46 | .41 | .54 | ||||

| Denial | .31 | .30 | .53 | .54 | .27 | .39 | .50 | .44 | .45 | .55 | |||

| Meds | .28 | -.19 | .18 | .21 | |||||||||

| Group tx | .20 | ||||||||||||

| Individual tx | .20 | .19 | .19 | .24 | |||||||||

| On own | -.30 | -.21 | .25 | .22 | .20 | .27 | .24 |

See Table 1 for exact terms used

3.3 Treatment Endorsement

Smokers recommended all three treatments for smoking cessation and did not recommend quitting on one's own (Table 1). Those with higher addiction ratings were more likely to endorse medication and individual counseling, and less likely to endorse quitting on one's own (Table 2). Similar findings were found for those with higher endorsement of biological factors. Greater ratings of the importance of willpower, motivation, and weak character were associated with greater endorsement of quitting on one's own. However, all the above correlations were numerically small (< .30), accounting for < 10% of the variance in endorsement of treatment seeking. In addition, some expected outcomes were not found; e.g. endorsement of lack of willpower as important was not inversely correlated with endorsement of medication.

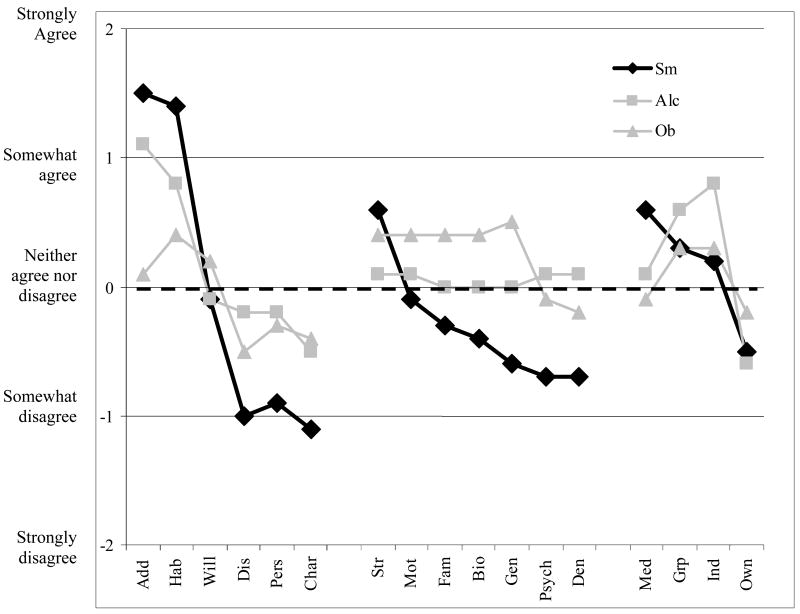

3.4 Comparisons Across Problems

The endorsement of most causes varied across the three scenarios (Figure 1 and last column, Table 3 for those p< .05). Addiction, habit and stress were more highly rated for inability to stop smoking than for inability to stop problem alcohol use or loss of excessive weight. Medication was more highly endorsed for quitting smoking than stopping alcohol use or losing weight. Several other causes were endorsed less for smoking than for alcohol or weight change. Smokers who had past or current alcohol problems or who were obese did not differ in how they rated the causes of inability to stop alcohol use or lose weight compared to smokers who had not had these problems.

Figure 1.

Ratings of causes of the inability to stop smoking or problem alcohol use or to lose weight. See Table 1 for definitions of all abbreviations. A score of zero means neither agree nor disagree, +1 = agree somewhat, +2 = agree strongly, -1 = disagree somewhat, -2 = disagree strongly.

4. Discussion

Smokers attributed continued smoking despite problems to addiction, habit and stress (Cunningham et al., 1994; Eiser et al., 1977; Balmford et al., 2008). This suggests smokers see inability to stop as due to multiple different causes. In the study most similar to ours, done over 25 yrs ago, 71% of the general public stated tobacco use was an addiction (cf our 88% in our more recent sample of smokers only) and 75% stated it was a “habit, not disease” (cf. our 88%) (Cunningham et al., 1994). Surprisingly, only a minority of smokers attributed the inability to quit to lack of willpower or motivation. In prior surveys, over 80% of smokers have said these were important (Balmford et al., 2008). One possible reason for our different results is that we surveyed smokers, not the general public. Also, we used a concrete scenario that emphasized prior inability to stop and use of tobacco despite problems. Finally, we intentionally did not ask about the smokers' own smoking because smokers often believe they do not conform to the norm for smokers.(Weinstein et al., 2004). Such differences in ratings for “actor/observer” scenarios are common (Malle, Knobe, & Nelson, 2007). Nevertheless, our unexpected finding requires replication.

Few smokers endorsed face-valid causes of the inability to quit smoking such as disease, personality problems, weakness of character, family/upbringing, biological factors, and genetics. Some of this may have been due to the terms we used (e.g. “mental disease” vs “disease”) or due to a lack of knowledge; e.g. most smokers are not aware of genetic factors (Wright, Weinman, & Marteau, 2003).

Habit and addiction endorsements were positively correlated. The one prior test of this relationship found a similar result (Cunningham et al., 1994). In contrast, prior scientists have argued that endorsement of “habit” and “addiction” are mutually exclusive (Perkins, 1999; Davis, 1992) and, thus, should be negatively correlated. Clearly, further research is needed to determine whether use of the term habit implies non-addiction to the lay public.

Although scientists often link addiction to biological factors (Leshner, 1997), smokers' endorsements of addiction were not related to endorsements of biological or genetic causes. Whether this is because smokers are unaware of the biological or genetic factors or whether they believe endorsement of addiction does not require endorsement of biological factors is unknown.

The central construct of scientific theories of addiction/dependence is that the disorder causes impaired control over drug use (Piper, McCarthy, & Baker, 2006). If this is the case, then the more one believes inability to stop is an addiction, the less they should believe inability to stop is due to willpower and, in fact, this is what we and others (Cunningham et al., 1994) have found. On the other hand, one would think the same relationship would occur between addiction and motivation but we did not find this. Clearly more research on how smokers perceive the relationships among addiction, willpower and motivation is needed.

Higher ratings of addiction were positively related to treatment seeking and higher ratings of willpower and motivation were related to endorsing quitting without treatment. This is consistent with findings for other behavioral problems. For example, when asked about substance-use and non-substance use psychological problems, those who conceptualize a problem as a bad habit/character flaw/personality problem/sin/moral failure rather than a medical/psychological disorder/disease/addiction are less likely to seek treatment (Cunningham et al., 1993; Moyers & Miller, 1993; West & Power, 1995a; Varney et al., 1995; cunningham, Blomqvist, & Cordingley, 2007; Cunningham et al., 1996). More specifically, those who believe biology causes a drug problem or mental illness have more favorable attitudes toward medication whereas those who believe environment causes mental illness have more favorable attitudes toward psychotherapy (Kuppi & Carpiano, 2006; Iselin & Addis, 2003; cunningham et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 1993). However, the relationship between ratings of causes and endorsement of treatments in the current study was small, suggesting other factors are more important in determining treatment seeking.

As stated earlier, interpretations of comparisons across problem behaviors must be cautious because almost all the participants had had personal problems stopping smoking, but few had personal problems stopping problematic alcohol use or losing excessive weight. Even though participants were asked to rate a fictional other person, their own experiences of lack thereof may have influenced these ratings. Future studies could survey persons who have a history of problems changing two or three behaviors to provide a within-subject comparison that should be a more fair comparison.

As noted above, we failed to find several expected relationships and several unexpected ones occurred. One possible explanation for this is that, although our small pilot suggested little confusion about our “causes”, there is significant heterogeneity in how smokers interpret the 1-3 word causes we used. If so, then psychometrically-developed multi-item scales (Schaler, 1995; Humphreys et al., 1996; Luke et al., 2002) may be necessary to find more valid results. Thus, qualitative studies to obtain a better understanding of smokers ideas, beliefs, attitudes and definitions of causes may be needed before further research is undertaken. In retrospect, we should have done such a study prior to undertaking the current study.

Another possible explanation for our unexpected results is that smokers really have not put much time into thinking about causes of the inability to stop smoking (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). If so, then their responses may be unreliable or reflect more what they believe is the norm rather than their own personal beliefs. Several lines of evidence suggest that often when participants are asked beliefs they are “telling more than they can know” and this clearly could be the case for our smokers (Nisbett et al., 1977).

The major assets of the study were its focus on one group of substance users (i.e. tobacco smokers), the inclusion of a large number of different perceived causes, the use of concrete scenarios, the comparison groups of alcohol users and obese persons, and the randomization of participants to different scenarios. One possible limitation of the current study is that it recruited via internet and the response rate is unknown; however, the sample did not appear to be younger, more affluent, or more educated. Minorities were under-represented in the current study and, it is clearly possible they endorse concepts differently. However, this method did not allow us to ascertain the response rate or sample bias. Another limitation is that we used only current smokers; thus, our results may not generalize to ex smokers or never smokers. We did not vary the order of questions across participants and used only a single word or phrase to convey causes. Finally, as stated above, our use of brief phrases to define causes may have been too vague. A preliminary qualitative study to produce better descriptors of causes may be necessary to obtain more valid results.

In terms of significance, although scientists may argue that certain concepts are antithetical (e.g. addiction vs habit), many, if not most, smokers appear to not see contradictions in simultaneously endorsing what appear to be very different causes: i.e., addiction, habit, willpower and motivation, as causes of the inability to stop smoking. Thus, one implication of our results is that scientists cannot assume that smokers have the same network of concepts or the same denotative or connotative meanings of terms that scientists do.

Perceived causes were linked to treatment seeking; however, this relationship was weak. Thus, it is currently unclear whether changing perceptions about causes will change treatment seeking; e.g. a campaign to better convince smokers that smoking is an addiction and not due to low willpower may not necessarily increase treatment seeking.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Balmford J, Borland R. What does it mean to want to quit? Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:21–27. doi: 10.1080/09595230701710829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults - United States 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;54:1121–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Chow VMC. What's in a label? The effects of substance types and labels on treatment considerations and stigma. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:693–699. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Freedman JL, Sobell MB. Beliefs about the causes of substance abuse: A comparison of three drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LS, Sobell MB. Are disease and other conceptions of alcohol abuse related to beliefs about outcome and recovery? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26:773–780. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J, Blomqvist J, Cordingley J. Beliefs about drinking problems: Results from a general population telephone survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RM. The language of nicotine addiction: purging the word “habit” from our lexicon. Tobacco Control. 1992;1:163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Eiser JR, Sutton SR, Wober M. Smokers, non-smokers and the attribution of addiction. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1977;16:329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1977.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius WV, Nagoshi CT, MacKinnon DP. Concepts of drugs: Differences in conceptual structure across groups with different levels of drug experience. Addiction. 1997;92:847–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K, Furgerg H. A comparison of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and smoking prevalence across countries. Addiction. 2008;103:841–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine L, Philogene G, Gramling R, Coups E, Sinha S. Prevalence of multiple chronic disease risk factors; 2001 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(Suppl):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Caroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999 - 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk H, Dar R. A Critique of Nicotine Addiction. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA. Epidemiology of tobacco use in the United States. Oncogene. 2002;21:7326–7340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Data to estimate similarity of tobacco research samples to intended populations. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:177–179. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Should criteria for drug dependence vary across drugs? Addiction. 2005;101:S134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Greenbaum MA, Noke JM, Finney JW. Reliability, validity, and normative data for a short version of the understanding of alcoholism scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Iselin MG, Addis ME. Effects of etiology on perceived helpfulness of treatments for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Wilkinson DA, Skinner W, Kent C, Franklin T, Pope M. Comparing tobacco cigarette dependence with other drug dependences. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261:898–901. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.6.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppi S, Carpiano RM. Public conceptions of serious mental illness and substance abuse, their causes and treatments: Findings from the 1996 General Social Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1766–1770. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner A. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science. 1997;278:45–47. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Ribisl KM, Walton MA, Davidson WS. Assessing the diversity of personal beliefs about addiction: Development of the Addiction Belief Inventory. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37:89–120. doi: 10.1081/ja-120001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle B, Knobe J, Nelson S. Actor-observer asymmetries in explanations of behavior: New answers to an old question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:491–514. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Miller WR. Therapists' conceptualizations of alcoholism: Measurement and Implications for treatment decisions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Murgraff V, Parrott A, Bennett P. Risky single-occasion drinking amongst young people--definition, correlates, policy, and intervention: A broad overview of research findings. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:3–14. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett R, Wilson T. Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review. 1977;84:231–259. [Google Scholar]

- Peele S. Diseasing of America: Addiction Treatment Out of Control. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K. Tobacco smoking is a ‘dependence’, not a ‘habit’. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 1999;1:127–128. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Baker TB. Assessing tobacco dependence: A guide to measure evaluation and selection. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8:339–351. doi: 10.1080/14622200600672765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva G, Bacchetta M, Cesa G, Conti S, Castelnuovo G, Mantovani F, et al. Is severe obesity a form of addiction?: Rationale, clinical approach, and controlled clinical trial. Cyberpsychology Behavior. 2006;9:457–479. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaler JA. The Addiction Belief Scale. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:117–134. doi: 10.3109/10826089509060737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varney SM, Rohsenow DJ, Dey AN, Myers MG, Zwick WR, Monti PM. Factors associated with help seeking and perceived dependence among cocaine users. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:81–91. doi: 10.3109/00952999509095231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N, Slovic P, Gibson G. Accuracy and optimism in smokers' beliefs about quitting. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:S375–S380. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Power D. Alcoholics' beliefs about responsibility for, and recovery from, their condition. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1995a;14:55–62. doi: 10.1080/09595239500185061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Power D. Alcoholics' beliefs about responsibility for, and recovery from, their condition. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1995b;14:55–62. doi: 10.1080/09595239500185061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The impact of learning of a genetic predisposition to nicotine dependence: An analogue study. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:227–230. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]