Abstract

Context: Complex changes in GnRH secretion occur with aging in women, but little is known about the effect of aging on the pituitary per se.

Objective: The aim of the study was to determine whether pituitary responsiveness to GnRH is attenuated with aging.

Design and Setting: A GnRH antagonist and graded doses of GnRH were used to isolate pituitary responsiveness in Clinical Research Center studies at an academic medical center.

Subjects: Subjects were healthy postmenopausal women (PMW) aged 48–57 yr (n = 10) or 70–77 yr (n= 9).

Interventions: A suppressive dose of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist (150 μg/kg sc) was administered and was followed by GnRH doses of 25, 75, 250, or 750 ng/kg iv every 4 h.

Results: The LH response to GnRH was attenuated with aging (P = 0.05) with an interaction between age and dose (P = 0.01) such that the LH amplitude was less in older PMW at the higher doses (250 ng/kg, 50 ± 9 vs. 29 ± 4.9 IU/liter, for young and old PMW, respectively, P = 0.02; and 750 ng/kg, 97.7 ± 11 vs. 70.2 ± 9.3 IU/liter, P = 0.002), but not the lower doses of GnRH. The FSH response to GnRH was also attenuated with aging in PMW (P = 0.005).

Conclusions: In studies that isolated the pituitary from endogenous GnRH stimulation, aging attenuated the LH and FSH responses to exogenous GnRH in PMW. These studies indicate that the pituitary plays a role in the decline in gonadotropin levels with aging, further supporting the potential contribution of age-associated changes in both hypothalamic and pituitary function to reproductive senescence.

Studies using a hypothalamic clamp to isolate the pituitary from endogenous GnRH input in postmenopausal women demonstrate that the LH and FSH responses to GnRH are diminished with aging.

Aging is accompanied by changes in multiple neuroendocrine axes (1). There is a decrease in estrogen in women (menopause), testosterone in men (andropause), dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (adrenopause), and GH and IGF-I (somatopause) with aging as well as changes in glucose metabolism and vasopressin secretion. Recent studies have challenged traditional views on aging by suggesting that many of the observed endocrine changes reflect altered stimulation of target endocrine organs rather than aging of the target organs per se. There is substantial evidence in rodents, for example, that neuroendocrine changes that occur with aging contribute to reproductive senescence (2). Evidence has also accumulated in humans that dynamic changes in neuroendocrine function occur with aging in the reproductive system beyond those secondary to the loss of gonadal function, and thus, the model of reproductive aging in women and men is now shifting to one of age-specific alterations in multiple components of the reproductive axis (3).

Postmenopausal women (PMW) are ideal subjects in whom to study the effects of aging on the hypothalamic and pituitary components of the reproductive axis. The loss of ovarian feedback at the time of menopause creates an open loop system in which the effect of aging on the neuroendocrine components of the axis can be examined in the absence of the changing gonadal feedback milieu of the normal menstrual cycle or the perimenopause. After the marked rise in FSH and LH levels in response to the decline in ovarian feedback with menopause, there is a steady decline in LH and FSH levels with age (4,5). Previous studies in PMW have documented a decrease in the frequency of pulsatile GnRH secretion with aging (6,7,8), but an increase in the overall amount of GnRH secreted (9), implying an increase in the bolus of each GnRH pulse. These hypothalamic changes in the pattern of GnRH secretion would be expected to increase, rather than decrease, both FSH and LH based on the results of in vitro and in vivo studies (10,11,12) and therefore suggest that aging is also associated with a decrease in the pituitary response to GnRH.

Some, although not all, studies of isolated rat pituitary cells provide evidence for an effect of aging on basal gonadotropin secretion and/or responses to GnRH (13,14,15,16,17,18,19). Studies in PMW that have attempted to assess the effect of aging on the pituitary have also produced conflicting results (6,7,8,20,21,22,23). A significant drawback of previous studies in PMW is that they have failed to isolate the pituitary response from endogenous GnRH input. This is particularly important because the LH amplitude response to exogenous GnRH is critically dependent on the preceding interpulse interval (24), which is markedly altered with aging (6,8,21,23) and may have confounded previous studies.

To address the hypothesis that the pituitary response to GnRH is blunted with aging in women, we have developed a model that controls both the amount of GnRH stimulation of the gonadotrope and the preceding interpulse interval. To create this GnRH clamp, a dose of a competitive GnRH antagonist that has previously been shown to provide maximum receptor blockade in PMW (25) was administered to young and old PMW, followed by graded doses of GnRH administered at a fixed interval. The results of these studies provide compelling evidence that the pituitary response to GnRH is attenuated with aging in women.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Young (48–57 yr; n = 10) and old (70–77 yr; n = 9) PMW were studied. All subjects were healthy and had experienced their last menstrual period a minimum of 24 months previously. Thus, both the younger and older women were postmenopausal as defined by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop criteria (26). No subjects were on any medications known to interact with the neuroendocrine reproductive axis, and none were using over-the-counter menopause preparations or herbal supplements. Prolactin, TSH, complete blood count, renal function tests, and an electrocardiogram were normal in all subjects. Subjects took ferrous gluconate 324 mg/d for 2 months, beginning 1 month before the study.

The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee and the Food and Drug Administration, and signed informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation.

Experimental protocol

Subjects were admitted to the Clinical Research Center of the Massachusetts General Hospital for a 28-h period beginning at 0800 h (Fig. 1). Blood was sampled every 30 min through an antecubital iv catheter for 4 h to assess baseline secretion. Patients then received a 150 μg/kg sc injection of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist. Blood sampling continued every 30 min for 7 h to document the decline in gonadotropin levels after GnRH receptor blockade and then increased to every 10 min. Beginning 8 h after antagonist administration, GnRH doses of 25, 75, or 250 ng/kg were given iv every 4 h in random order, and 750 ng/kg was administered 4 h later. Estradiol (E2) was measured at baseline, and all blood samples were assayed for LH and FSH.

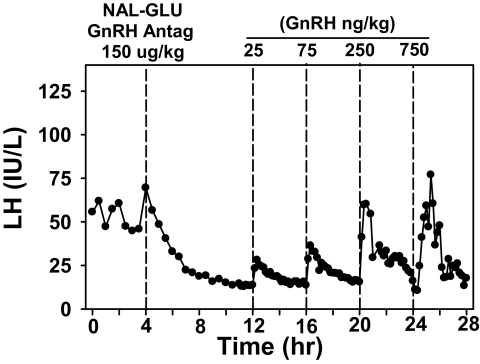

Figure 1.

Serum LH during the 28-h study in a representative subject. Beginning at 0800 h, blood was sampled every 30 min for 4 h to assess baseline secretion. The subject then received a sc injection of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist. Beginning 8 h after GnRH receptor blockade, GnRH doses of 25, 75, 250, and 750 ng/kg were administered iv at 4-h intervals. LH is expressed in IU/liter, as equivalents of the 2nd International Reference Preparation of human menopausal gonadotropins.

GnRH was obtained from Polypeptides (Torrance, CA) and formulated in the Research Pharmacy of Massachusetts General Hospital. The NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist was obtained from the Contraceptive Development Branch of the National Institutes of Health and formulated as previously described (27). The dose of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist and the time between antagonist and GnRH administration is based on previous studies in PMW that established the maximum suppressive dose of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist and LH elimination kinetics in PMW (25). Preliminary studies in which GnRH was administered over the range of 15 to 1500 ng/kg established that GnRH doses between 25 and 750 ng/kg would effectively compete with 150 μg/kg of the NAL-GLU GnRH antagonist and revealed the absence of a priming effect in this model.

Assays

Serum LH and FSH were measured using a two-site monoclonal nonisotopic system (Axsym; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), as previously described (28,29). LH and FSH were expressed in international units per liter, as equivalents of the Second International Reference Preparation 71/223 of human menopausal gonadotropins. The assay sensitivity for both LH and FSH is 1.6 IU/liter. The intraassay coefficients of variation (CV) for LH and FSH are less than 7% and less than 6%, respectively, with interassay CVs for both hormones of less than 7.4%. E2 was measured using a direct immunoassay (Architect i2000; Abbott Laboratories) which has a sensitivity of 5 pg/ml (18.4 pmol/liter) and a functional sensitivity of 15 pg/ml (55.1 pmol/liter) (30). The intraassay CV for E2 is 6.4%, and the interassay CV is 10.6%.

Data analysis

Baseline LH and FSH were calculated from the arithmetic mean of the 4-h pretreatment measurements. LH and FSH amplitudes were calculated as the difference between the nadir within ±10 min of GnRH administration and the subsequent peak for each dose. Amplitude was also expressed as a percentage of baseline. Data that were not normally distributed were log-transformed before analysis. Student’s t tests were used for comparison of baseline values between young and old PMW. ANOVA for repeated measures was used for determination of the effect of age on the LH and FSH responses to GnRH, with age expressed as a categorical variable. Similar analyses were performed using years after menopause or years after menopause or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as the categorical variables. Multiple linear regression was used to determine the effect of body mass index (BMI) and ambient E2 levels on the mean LH and FSH responses to GnRH. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The younger PMW were 52.9 ± 0.8 yr old, and the older PMW were 72.8 ± 0.8 yr old. Three older subjects had undergone bilateral oophorectomy in the past, whereas the majority experienced natural menopause. Ninety percent of the younger women and 44% of the older women had never taken hormone replacement. The younger women were on average 4.2 ± 1.0 yr after menopause and 3.6 ± 0.5 yr after menopause or HRT, whereas the older women were 27.34 ± 2.62 yr after menopause and 18.66 ± 4.84 yr after menopause or HRT. The mean weight and BMI of the participants was 75.2 ± 2.3 kg and 28.4 ± 0.8 kg/m2, respectively, and were not different between younger and older subjects. Menopausal status was confirmed in all subjects by low E2 [19.1 ± 2.6 pg/ml (69.7 ± 6.3 pmol/liter)] and elevated gonadotropins (LH, 71.6 ± 5.4 IU/liter; FSH, 119.8 ± 10.9 IU/liter). E2 levels were not significantly different between old and young PMW (18.3 ± 3.8 vs. 19.9 ± 3.6 pg/ml 67.2 ± 14 vs. 73.0 ± 13.2 pmol/liter for older and younger, respectively). LH and FSH were lower in older compared with younger PMW at baseline as seen previously, but the difference was statistically significant for FSH (101.6 ± 12.0 vs. 137.4 ± 15.0 IU/liter for older and younger women, respectively; P = 0.04) and not LH (71.0 ± 10.8 vs. 72.2 ± 5.0 IU/liter for older and younger, respectively, in the current study.

Effect of age on the LH response to GnRH

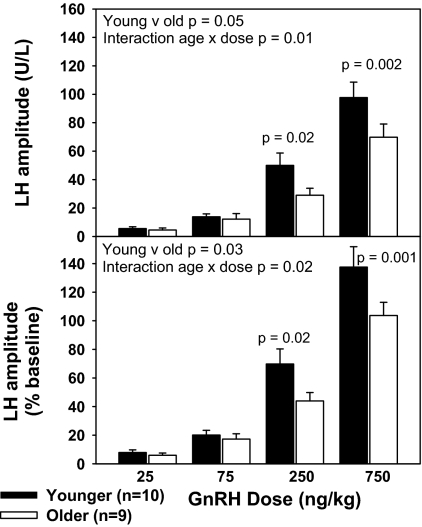

Increasing doses of GnRH were associated with a progressive increase in the amplitude of the LH response (P < 0.001), whether expressed as an absolute change or in relation to baseline (Fig. 2). LH levels in response to GnRH doses between 75 and 250 ng/kg spanned the physiologic range as determined by comparison with mean LH levels in PMW (6). The LH response to GnRH was attenuated with aging (P = 0.05), whether expressed as calendar age (older vs. younger) or years from menopause (≤15 yr vs. >15 yr). As expected by the lack of difference between the groups in BMI or baseline E2, this relationship was not altered by adjustment for either variable. There was a significant interaction between age and GnRH dose for LH amplitude (P = 0.01) such that younger subjects had a significantly greater LH amplitude than older subjects at GnRH doses of 250 ng/kg (P = 0.02) and 750 ng/kg (P = 0.002), but not at the lower two doses. When LH amplitude was expressed as a percentage change from baseline, there was also a decrease in responsiveness with aging (P = 0.03) and an interaction with dose (P = 0.02) such that responsiveness to GnRH was less in older women at doses of 250 ng/kg (P = 0.02) and 750 ng/kg (P = 0.001), whereas differences at the two lower doses were not statistically significant. The LH response to GnRH was not associated with time from estrogen exposure (years after menopause or HRT).

Figure 2.

Decrease in LH responsiveness to GnRH with aging in PMW. LH amplitude is expressed in absolute values (top) or as percentage change from baseline (bottom) in response to increasing doses of GnRH (25, 75, 250, and 750 ng/kg) in younger and older PMW after administration of a GnRH antagonist. LH is expressed in IU/liter, as equivalents of the 2nd International Reference Preparation of human menopausal gonadotropins.

Effect of age on FSH responses to GnRH

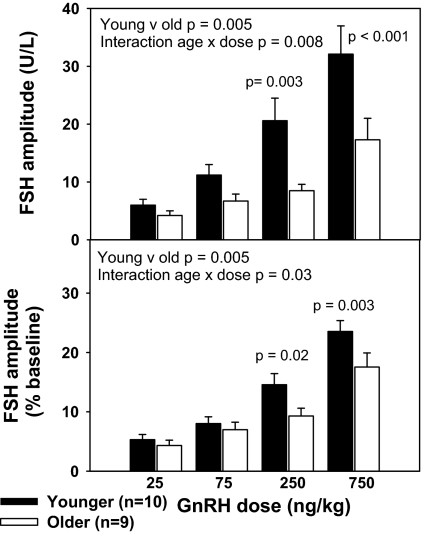

The FSH response to GnRH was also decreased in older compared with younger PMW. FSH amplitude, expressed absolutely and as a percentage change from baseline (Fig. 3), increased with increasing GnRH dose (P < 0.001) and was less in older compared with younger PMW (P = 0.005). This relationship persisted with adjustment for BMI and baseline E2 levels. The interaction between age and GnRH dose (P = 0.008) indicated a more prominent effect at the two higher doses (250 ng/kg, P = 0.003; and 750 ng/kg, P < 0.001). This interaction was maintained (P = 0.03) when FSH amplitude was expressed as a percentage change from baseline such that responsiveness to GnRH was less in older women at the two higher GnRH doses (250 ng/kg, P = 0.02; and 750 ng/kg, P = 0.003), but not the two lower doses. The effect of age on FSH responsiveness to GnRH was identical when age was expressed as years after menopause. However, FSH responsiveness to GnRH was not significantly related to years after estrogen exposure (years after menopause or HRT).

Figure 3.

Decrease in FSH responsiveness to GnRH with aging in PMW. FSH amplitude is expressed as absolute values (top) or as percentage change from baseline (bottom) in response to increasing doses of GnRH (25, 75, 250, and 750 ng/kg) in younger and older PMW after administration of a GnRH antagonist. FSH is expressed in IU/liter, as equivalents of the 2nd International Reference Preparation of human menopausal gonadotropins.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that there is a decrease in pituitary responsiveness to GnRH with aging in women using a novel model in which the pituitary is isolated from both endogenous GnRH input and gonadal feedback. These data provide compelling evidence that changes in the pituitary itself contribute to the decline in gonadotropin levels observed with aging in PMW. These findings are in agreement with the results of studies in isolated pituitary cells showing a decrease in LH and FSH release in gonadectomized rats with aging (13,14,15,16,18) or an inhibitory effect of age on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH in gonadectomized (14) and intact (13,14,17) animals. In the current study, we were unable to separate the effect of aging from that of years from menopause. However, we found no significant relationship between years from estrogen exposure (i.e. menopause or HRT) and pituitary responsiveness, suggesting that the effect of aging on pituitary responsiveness may be due to factors other than the loss of estrogen per se in PMW.

Previous studies in PMW have addressed the pituitary response to GnRH as a function of aging by measuring either the amplitude of pulsatile LH secretion or the pituitary response to exogenous GnRH. The decrease in LH pulse amplitude with aging that has been documented in some studies (6,8,21,23) has been interpreted as indicating that pituitary responsiveness is decreased with aging, but it has not been confirmed in all studies (7,20,22). This interpretation is confounded by the fact that LH pulse amplitude reflects the combination of hypothalamic input and pituitary responsiveness and therefore does not isolate the pituitary effect of aging. The effect of aging on the response to exogenous GnRH in PMW has been equally unclear with studies showing no change, a decrease, or an increase with age and/or years from menopause (7,8,22). This approach is confounded by the known effect of the preceding interpulse interval on the LH response to GnRH (24), which is particularly problematic in PMW due to the marked slowing of GnRH pulses with aging (6). Use of a competitive GnRH antagonist in the current study blocked the effect of endogenous GnRH, allowing us to control both the interpulse interval and the dose of GnRH administered. Importantly, the doses of GnRH used encompassed the physiological ranges of mean LH, LH pulse amplitude, and peak LH seen in PMW across a range of ages and years after menopause (6,9,31).

This study was based on previous findings from ourselves and others that showed a decrease in mean LH and FSH levels with aging (4,5). Precise control of GnRH frequency and dose has now revealed an inhibitory effect of aging on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH for both LH and FSH. It is of interest that the decrease in baseline gonadotropin levels in older compared with younger PMW was significant for FSH, but not LH, in the current study. Whereas baseline hormone levels will reflect a balance between pituitary responsiveness and the frequency and amplitude of hypothalamic GnRH stimulation, LH secretion is significantly more dependent on GnRH than is FSH (32). Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that baseline FSH levels more closely reflect the effect of aging on the pituitary itself in comparison to baseline LH whose regulation is more strongly influenced by the complex changes in GnRH secretion that have been documented with aging in women (6,9).

The gonadotrope response to GnRH depends not only on the amplitude and frequency of the GnRH signal, but also on the number of cells that express GnRH receptors (GnRHRs) and/or GnRHR density (33) as well as the intracellular signaling cascade (34). In women studied at autopsy, the proportion of gonadotropes compared with other pituitary cell types does not change as a function of aging (35), but there are no data on changes in GnRHR density with age. In the current studies, the one-time dose of GnRH antagonist blocked endogenous GnRH over several hours but may not have abolished the effect of prior exposure to endogenous GnRH on GnRHR. GnRH pulse frequency is known to decrease with age in PMW (6), and studies in cultured pituitary cells have shown that slower frequency GnRH pulses are associated with a decrease in GnRHR number (36). Our previous studies, however, also suggest that GnRH pulse amplitude increases with aging in PMW (3) which might be expected to negate a potential effect of decreased frequency on GnRHR number (33,37). In rodents, a decline in the number of GnRHR-containing cells, GnRHR number, or mRNA has been documented as a function of aging in intact (38,39), but not gonadectomized (40,41), animals, raising the possibility that these age-related changes in GnRHR in rodent models were related to changes in the steroid milieu rather than aging per se. In light of these studies, it seems unlikely that the attenuated pituitary response to GnRH with aging in PMW is mediated through a decline in GnRHR number. An intriguing alternative explanation is an age-related change in postreceptor signaling in the form of defective calcium mobilization, as has been observed in gonadotropes from both intact and gonadectomized old rats (14).

Although E2 levels have been shown to decrease with time after menopause (42), E2 levels were not different between younger and older PMW in the current study using a sensitive E2 assay and did not impact pituitary responsiveness. Moreover, whereas it is unclear whether or not E2 has a direct negative feedback effect on gonadotropin secretion at the pituitary (43), such an effect would be expected to result in an increase rather than a decrease in pituitary responsiveness to GnRH with aging. Testosterone levels also decrease with aging in women (44), but testosterone does not appear to have a direct inhibitory effect at the pituitary in women (45). Finally, although it has previously been shown that obesity has an inhibitory effect on gonadotropin secretion that appears to be mediated at the pituitary (46), BMI was not different between the younger and older PMW in the current study and did not impact pituitary responsiveness to GnRH.

In summary, these studies establish that decreased pituitary responsiveness to GnRH occurs with aging and likely contributes to the overall decline in gonadotropin secretion with aging in PMW. Our findings add to the current knowledge of reproductive senescence by suggesting that pituitary function is attenuated with aging. Although it is clear that the ovary plays a primary role in the loss of reproductive function in women, we can no longer ignore the potential contributions of the neuroendocrine components of the reproductive axis to the changing reproductive phenotype with aging. It remains to be determined whether the attenuated pituitary response to GnRH with aging in PMW reflects the influence of the changing pattern of GnRH stimulation over time or is due to contemporaneous aging of the pituitary itself.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. H. Lee and the Massachusetts General Hospital Biostatistics Center and Dr. Pat Sluss of the Massachussetts General Hospital Reproductive Endocrine Unit Assay Lab.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01 AG13241 and M01 RR1066. N.D.S. received fellowship support from the NIH (5T32 HD007396).

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov ID no. NCT 00386022.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online June 23, 2009

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CV, coefficients of variation; E2, estradiol; GnRHR, GnRH receptor; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; PMW, postmenopausal women.

References

- Lamberts SWJ 2008 Endocrinology and aging. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, eds. Williams’ textbook of endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, Kashon ML, Krajnak KM, Rosewell KL, Cai A, Scarbrough K, Harney JP, McShane T, Lloyd JM, Weiland NG 1997 Aging of the female reproductive system: a window into brain aging. Recent Prog Horm Res 52:279–303; discussion 303–305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE 2007 Neuroendocrine changes with reproductive aging in women. Semin Reprod Med 25:344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Collins WP, Forecast JD, Newton JR, Oram DH, Studd JW 1976 Hormonal profiles after the menopause. Br Med J 2:784–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE 2004 Neuroendocrine physiology of the early and late menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 33:637–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Lavoie HB, Marsh EE, Martin KA 2000 Decrease in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse frequency with aging in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1794–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambalk CB, de Boer L, Schoute E, Popp-Snyders C, Schoemaker J 1997 Post-menopausal and chronological age have divergent effects on pituitary and hypothalamic function in episodic gonadotrophin secretion. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 46:439–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmanith WG, Scherbaum WA, Lauritzen C 1991 Gonadotropin secretion during aging in postmenopausal women. Neuroendocrinology 54:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S, Sharpless JL, Rado K, Hall JE 2002 Evidence that GnRH decreases with gonadal steroid feedback but increases with age in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2290–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross KM, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ 1987 Differential control of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone secretion by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone pulse frequency in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Katt JA, Ortolano GA, el-Gewely MR, Duncan JA, Dee C, Marshall JC 1988 Influence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse amplitude, frequency, and treatment duration on the regulation of luteinizing hormone (LH) subunit messenger ribonucleic acids and LH secretion. Mol Endocrinol 2:338–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser UB, Sabbagh E, Katzenellenbogen RA, Conn PM, Chin WW 1995 A mechanism for the differential regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene expression by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:12280–12284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman MR, Mukherjee A, Tsitouras PD, Harman SM 1985 Decreased in vitro secretion of LH, FSH, and free α-subunits by pituitary cells from old male rats. Am J Physiol 249(2 Pt 1):E145–E151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuknyiska RS, Blackman MR, Roth GS 1987 Ionophore A23187 partially reverses LH secretory defect of pituitary cells from old rats. Am J Physiol 253(3 Pt 1):E233–E237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haji M, Roth GS, Blackman MR 1984 Excess in vitro prolactin secretion by pituitary cells from ovariectomized old rats. Am J Physiol 247(4 Pt 1):E483–E488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaler LW, Critchlow V 1984 Anterior pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion during continuous perifusion in aging male rats. Mech Ageing Dev 25(1–2):103–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegle GD, Meites J, Miller AE, Wood SM 1977 Effect of aging on hypothalamic LH-releasing and prolactin inhibiting activities and pituitary responsiveness to LHRH in the male laboratory rat. J Gerontol 32:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DA, Blackman MR, Kowatch MA, Danner DB, Roth GS 1990 Discordant effects of aging on prolactin and luteinizing hormone-β messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the female rat. Endocrinology 126:773–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LK, Tang FY 1981 LH responses to LHRH, DBcAMP, and 17 β-estradiol in cultures derived from aged rats. Am J Physiol 240:E510–E518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SE, Aksel S, Hazelton JM, Yeoman RR, Gilmore SM 1990 The effect of aging on hypothalamic function in oophorectomized women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162:446–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genazzani AD, Petraglia F, Sgarbi L, Montanini V, Hartmann B, Surico N, Biolcati A, Volpe A, Genazzani AR 1997 Difference of LH and FSH secretory characteristics and degree of concordance between postmenopausal and aging women. Maturitas 26:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmanith WG, Reichelt C, Scherbaum WA 1994 Neuroendocrinology of aging in humans: attenuated sensitivity to sex steroid feedback in elderly postmenopausal women. Neuroendocrinology 59:355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro N, Banwell T, Tortoriello D, Lieman H, Adel T, Skurnick J 1998 Effects of aging and gonadal failure on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 178:732–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea LS, Finkelstein JS, Schoenfeld DA, Butler JP, Crowley Jr WF 1989 Interpulse interval of GnRH stimulation independently modulates LH secretion. Am J Physiol 256(4 Pt 1):E510–E515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless JL, Supko JG, Martin KA, Hall JE 1999 Disappearance of endogenous luteinizing hormone is prolonged in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:688–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods N 2001 Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). Climacteric 4:267–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Taylor AE, Martin KA, Rivier J, Schoenfeld DA, Crowley Jr WF 1994 Decreased release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone during the preovulatory midcycle luteinizing hormone surge in normal women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:6894–6898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK, Pagan YL, Smith PC, Rado KB, Hall JE 2003 Control of follicle-stimulating hormone by estradiol and the inhibins: critical role of estradiol at the hypothalamus during the luteal-follicular transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1766–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK, McNicholl DJ, Taylor AE, Hall JE 1999 Female reproductive aging is marked by decreased secretion of dimeric inhibin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluss PM, Hayes FJ, Adams JM, Barnes W, Williams G, Frost S, Ramp J, Pacenti D, Lehotay DC, George S, Ramsay C, Doss RC, Crowley Jr WF 2008 Mass spectrometric and physiological validation of a sensitive, automated, direct immunoassay for serum estradiol using the Architect. Clin Chim Acta 388:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S, Lavoie HB, Bo-Abbas Y, Hall JE 2002 Negative feedback effects of gonadal steroids are preserved with aging in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2297–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Brodie TD, Badger TM, Rivier J, Vale W, Conn PM, Schoenfeld D, Crowley Jr WF 1988 Evidence of differential control of FSH and LH secretion by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the use of a GnRH antagonist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67:524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loumaye E, Catt KJ 1982 Homologous regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors in cultured pituitary cells. Science 215:983–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H, Hew CL, Urano A 2001 Signal transduction pathways and transcription factors involved in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated gonadotropin subunit gene expression. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 129:525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T, Kovacs KT, Scheithauer BW, Young Jr WF 1993 Aging and the human pituitary gland. Mayo Clin Proc 68:971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser UB, Conn PM, Chin WW 1997 Studies of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) action using GnRH receptor-expressing pituitary cell lines. Endocr Rev 18:46–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BR, Duval DL, Mulvaney JM, Roberson MS, Clay CM 1999 Homologous regulation of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene is partially mediated by protein kinase C activation of an activator protein-1 element. Mol Endocrinol 13:566–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian J, Cooper RL, Conn PM 1981 Regulation of the rat pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Mol Pharmacol 19:399–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai T, Roth GS 1999 Mechanisms of age-related changes in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid content in the anterior pituitary of male rats. Exp Gerontol 34:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belisle S, Bellabarba D, Lehoux JG 1990 Hypothalamic-pituitary axis during reproductive aging in mice. Mech Ageing Dev 52:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag WE, Forman LJ, Fiori JM, Hylka VW, Meites J 1984 Decreased ability of old male rats to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) is not due to alterations in pituitary LH-releasing hormone receptors. Endocrinology 114:1657–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers MR, Zheng H, McConnell D, Nan B, Harlow SD, Randolph Jr JF 2008 Estradiol rates of change in relation to the final menstrual period in a population-based cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3847–3852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ 2002 Multifarious effects of estrogen on the pituitary gonadotrope with special emphasis on studies in the ovine species. Arch Physiol Biochem 110:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR 2005 Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3847–3853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaif A 1986 Do androgens directly regulate gonadotropin secretion in the polycystic ovary syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 63:215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagán YL, Srouji SS, Jimenez Y, Emerson A, Gill S, Hall JE 2006 Inverse relationship between luteinizing hormone and body mass index in polycystic ovarian syndrome: investigation of hypothalamic and pituitary contributions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1309–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]