Treatment of risk factors in patients who have had coronary artery bypass surgery improves their prognosis.1,2 A national survey performed in Britain in 1994 showed that risk factor management was suboptimal in most patients who had had bypass surgery.3 This survey was carried out before the publication of landmark trials showing the benefit of reducing cholesterol concentration.4,5 To determine if secondary prevention has changed as the evidence has improved, we audited the management of patients who had had bypass surgery in Lothian over the past decade.

Subjects, methods, and results

We identified a random sample of 100 patients a year from 1988 to 1997 from the database of cardiothoracic surgery in our regional centre. We sent postal questionnaires to their general practitioners about current aspirin treatment, smoking status, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration and treatment and compared responses with local audit standards. We received completed questionnaires from 94 practices about 761 (76%) patients, of whom 563 were alive. Aspirin was prescribed to 451 (80%) patients, and 65 (12%) continued to smoke. Seventy patients (12%) had systolic pressure greater than 160 mm Hg and 43 (8%) had diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. These risk factors did not vary by year of operation.

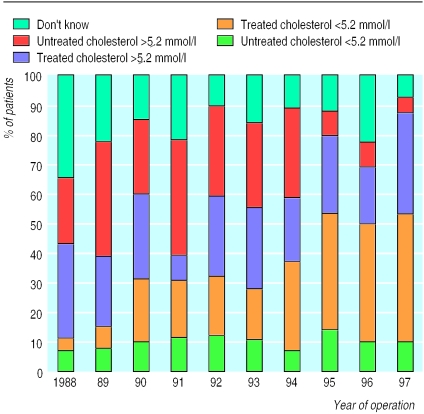

The proportion of patients with cholesterol measured and below the audit standard (<5.2 mmol/l) rose from 12% (5/42) for those operated on in 1988 to 50% (37/72) for those operated on in 1997. The proportion of patients with correctly managed cholesterol significantly increased for those operated on after publication of the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study in 1994 (figure, P<0.0001).4 Two hundred and seventy patients (48%) attended practices that had audited their management of secondary prevention, but the proportion of patients managed appropriately was virtually identical in audited and non-audited practices (37% (99/270) v 34% (99/291), P=0.956).

Comment

Our audit has shown that the standard of secondary preventative care was good for well established risk factors3 but less good for management of cholesterol. Although there has been considerable improvement over the past decade, 48% of patients were still not managed optimally in 1997. Patients who had bypass surgery before the 1994 study4 were less likely to receive cholesterol lowering treatment, probably because they had been discharged from specialist review and were less likely to consult their general practitioner.

The proportion of patients with suboptimally managed cholesterol was similar in practices that had and had not audited their secondary prevention. Many of the audited practices had participated in an audit organised by the local primary care audit team shortly before our survey, and improvement in care may have not yet been evident. However, audits usually identify patients by a diagnosis of myocardial infarction or the prescription of drugs for angina and may not identify coronary bypass patients. Use of hospital databases could improve identification of patients who would benefit from treatment. Our survey did not include data on patient compliance, which may also be an important factor.

In 1999, Lothian Health initiated a further project using a computer based audit package to identify patients and ensure that they are assessed within general practice. This project is funded to enable the practice teams to devote sufficient time to the process. To date 74 practices out of 125 within Lothian have enrolled to participate. Our results suggest that this project has the potential to improve secondary prevention in many patients with coronary heart disease, but it will need to be assessed by future audit.

Figure.

Measurement and treatment of raised cholesterol concentration among patients by year of coronary artery bypass surgery

Footnotes

Funding: The project was supported by grants from Pfizer and Parke-Davis and the Royal Infirmary audit department.

Competing interests: Merck Sharp and Dohme sponsored a visit by PB to the American College of Cardiology annual meeting. He has also carried out sponsored research for Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, all of whom make statins. RJI has also received sponsorship to attend a meeting in the United States from Merck Sharpe and Dohme.

References

- 1.Campeau L, Knatterud G, Domanski M, Hunninghake D, White C, Geller N, et al. The effect of aggressive lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and low-dose anticoagulation on obstructive changes in saphenous-vein coronary-artery bypass grafts. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:153–162. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavender JB, Rogers WJ, Fisher LD, Gersh BJ, Coggin CJ, Myers WO. Effects of smoking on survival and morbidity in patients randomized to medical or surgical therapy in the coronary artery surgery study (CASS): 10-year follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowker TJ, Clayton TC, Ingham J, McLennan NR, Hobson HL, Pyke SDM, et al. A British Cardiac Society survey of the potential for the secondary prevention of coronary disease: ASPIRE (action on secondary prevention through intervention to reduce events) principal results. Heart. 1996;75:334–342. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]