It’s difficult to imagine a more politically charged Canadian clinical trial than the joint industry-government study (www.cmaj.ca/earlyreleases/4aug09_enzyme.shtml) that has given patients with Fabry disease in this country access to costly enzyme replacement therapy for the past 2.5 years.

The players in this drama — patient advocacy groups, industry, the federal and provincial governments, and researchers — differ on the purpose and usefulness of the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative study, a 10-year clinical investigation that was launched with only a three-year funding agreement in place.

The study has not been fully enrolled, yet the funding agreement ends Sept. 30, leaving the 133 patients who receive treatment through the study uncertain about who will pay for their approximately $300 000 a year per person enzyme replacement therapy.

“Patients have become pawns; they are really tossed around like ping pong balls,” says Durhane Wong-Rieger, president of the Canadian Organization for Rare Diseases.

What is not disputed is that the study was created largely in response to “the need for patient access to treatment,” as the study’s independent scientific oversight committee states in its first annual report.

The phase 4 (post market approval) trial has several purposes: it includes a head-to-head comparison of the two approved therapies, acts as a registry of Fabry patients in Canada (not all of whom qualify for treatment under current guidelines) and, according to its first annual report, “could serve as a model for funding of other expensive drugs for rare diseases in Canada.”

It also has some unusual features: no formal sponsor has been identified, the confidential three-year funding agreement for the study has been withheld even from the principal investigators, and funding was only secured for the first three years.

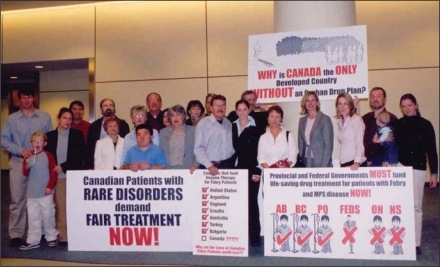

Canadian patients with rare disorders, and their advocates, held a vigil at the October 2005 meeting of federal, provinical and territorial health ministers, calling for a national orphan disease drug plan.

Fabry disease is a rare hereditary genetic condition that is estimated affect 1 in 40 000 men and twice as many women, although life-threatening complications, such as renal impairment and stroke, are much more rare among women.

The future of the study is in doubt because Health Canada, which has contributed more than $30 million to date — representing about 1/3 of the cost of the three-year funding agreement, tagged at $100 million in a May, 2006 presentation — has stated that it will not renew its funding after Sept. 30.

That leaves the provinces to negotiate with therapy manufacturers GenzymeCanada Inc. and Shire Human Genetics Inc. to determine if and how they can extend the study.

The therapy’s cost, as well as questions about its clinical benefits and the relative merits of the two versions of the therapy, help explain the study’s origins.

Wong-Rieger contends that the study is “a research answer to a political problem.”

But to Health Canada, its purpose is to “learn more about the effects of these two drugs and, more generally, to better understand the research challenges associated with drugs that treat small populations,” spokesperson Gary Holub states in an email.

Still, few could argue that a political problem preceded the study’s creation. Unlike countries such as the United States, Australia and Japan, Canada lacks a national policy to address orphan diseases — the often genetically based diseases like Fabry that affect a small proportion of the population and for which treatment is typically very expensive.

The issue of expensive drugs for rare diseases was one of the five priority elements under the National Pharmaceutical Strategy, which was developed as a result of the 2004 federal-provincial Health Accord. But the strategy has been dormant for a couple of years and the current federal government has frequently asserted that health care — and payment for pharmaceuticals — falls under provincial jurisdiction.

A brief history of events surrounding the controversy:

January 2004: Health Canada approves agalsidase beta (Genzyme) and agalsidase alfaGenzyme (Replagal) for marketing.

November 2004 and May 2005: The Common Drug Review, a national body that reviews of the clinical and cost effectiveness of drugs, recommends against the provincial funding for, respectively, Replagal and Genzyme, under public drug plans because of the high costs and because “clinically meaningful outcomes have not been proven.” But the national body may not be the appropriate one to review expensive drugs for rare diseases since they “are not going to be conventionally cost effective,” explains Dr. Andreas Laupacis, former head of the Common Drug Review’s Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committe.

March 2005: Many patients, who had been receiving enzyme replacement therapy through manufacturer-sponsored clinical trial participation and compassionate access programs, were cut off from treatment.

October 2005: Patient groups stage a two-day vigil Oct. 22–23 at the Toronto meeting of federal, provincial and territorial health ministers to protest the absence of a national orphan disease policy.

November 2005: Clinician researchers are invited to a Montreal meeting — convened by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ) and attended by officials from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and Health Canada — and are asked to develop a trial protocol.

December 2005: A protocol for a three-year study is submitted to the Canadian Institutes for Health Research by the Canadian Fabry Enzyme Replacement Consortium. The document, which was revised in March 2006, states: “As a result of some continuing uncertainty concerning the effectiveness of ERT [enzyme replacement therapy], along with the extraordinarily high cost of the treatment, approval of reimbursement for ERT for Fabry disease in Canada has been made conditional on the establishment of a formal research protocol to better document its true clinical impact in Canadian patients.” The CIHR did not fund the study and the final protocol for the Canadian Fabry Disease Initiative Study varies slightly from the earlier version.

May 13, 2006: The Canadian Fabry enzyme replacement therapy post market study is announced at a Halifax meeting. A presentation states that the decision to fund the study was made because of the negative recommendation from the Common Drug Review, the high cost of the therapy and “variable access to treatment based on provincial situation.” The “variable access” comment reflects the fact that Nova Scotia, a relatively small province, is home to the largest proportion of Canadians with Fabry disease.

January 2007: formal enrolment of patients in the trial begins.

Dr. Michael West, principal investigator for the 10-year trial, says he agreed to participate primarily to gain access to therapy for his patients. “It is not like we started this study. We have shown up to do it.”

The CIHR, which administers the federal contribution to the study, convened an independent scientific oversight committee to scrutinize the trial results. But when the oversight committee recommended that the CIHR become the study sponsor, the CIHR declined on the basis that it is not a funder and “does not exercise any control over the study.”

The trial is like “the ugly stepchild that no one wants” to sponsor, comments Wong-Rieger. Her organization and the Canadian Fabry Association, both of which receive funding from Genzyme and Shire Human Genetics, want provinces to pick up the tab for the enzyme replacement therapy rather than have the trial continue.