Abstract

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a failure to achieve the growth potential of a fetus that is promised by the genetic constitution and environmental influences endogenous to the pregnancy. Optimal placental development and the ability of the placenta to compensate for stimulus-induced injury are central in promotion of normal fetal growth. In this review, we will overview placental development with a focus on how villous structure relates to function. We will also describe the differentiation and turnover of villous trophoblast while highlighting selected features of microscopic placental injury. Histopathological studies of the placenta in IUGR indicate that abnormalities of the maternal spiral arterioles, dysregulated villous vasculogenesis, and abundant fibrin deposition are characteristic of the injuries associated with this condition. We identify selected insults, including oxidative stress and complement activation, and key pathways that regulate apoptosis in villous trophoblast, including increased p53 activity, altered translation of AKT and mTOR proteins, and the stress response of the endoplasmic reticulum. We surmise that trophoblast dysregulation at a subcellular level and loss of functional mass of villous trophoblast via cell death pathways are key contributors to the suboptimal placental performance that yields IUGR. We predict that a better understanding of placental dysfunction in IUGR will lead to targeted therapeutic options for this important clinical condition.

What is intrauterine growth restriction?

Fetal growth depends on the interactions of genetic and epigenetic determinants functioning against an environment of maternal, fetal, and placental influences (Gardosi et al. 1992). Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a failure to achieve the growth potential promised by these factors. IUGR manifests as a variable syndrome of suboptimal growth and body disproportions rather than a well-defined etiologic entity. Causes for IUGR are diverse and include aneuploidies, non-aneuploid syndromes, infections, metabolic factors and placental disorders.

IUGR places the fetus and neonate at risk of death or disability in the perinatal period (Baschat et al. 2000; Bernstein et al. 2000) and predisposes the child to a lifelong increased risk for hypertension, cardiovascular disorders and renal disease, among others (Murphy et al. 2006). The magnitude of the risk varies depending on the a priori risk of the population studied and the definition applied for the diagnosis of IUGR. A common definition is an estimated fetal weight less than the 10th % for gestational age, although a fetal weight < 3rd % is a better predictor of perinatal mortality (McIntire et al. 1999). Sub-optimal growth in abdominal circumference, increased fetal head to abdominal circumference ratio, and oligohydramnios, individually or in combination, reflect placental dysfunction and portend fetal compromise (Miller et al. 2008). Doppler ultrasound refines the predictive value for poor outcomes at a given growth percentile (Rigano et al. 2001). Diminished fetal arterial and venous Doppler flows in key vascular beds predict worsening fetal acid base status (Rizzo et al. 1996; Baschat et al. 2004) and such findings frequently lead to delivery of a markedly premature baby to avoid in utero demise.

Placental dysfunction is the subject of this review. We will overview placental development with a focus on how villous structure relates to function in the second half of pregnancy. We will describe the differentiation and turnover of villous trophoblast while highlighting the histopathology of placental injury. We conclude with clinically important mechanisms for villous injury that contribute to placental dysfunction, with particular attention to loss of functional mass of villous trophoblast via cell death pathways.

How does the placenta normally develop?

The trophectoderm of the blastocyst is the epithelium responsible for evolution of the human placenta (Huppertz, 2008). Differentiation of trophectoderm forms multiple trophoblast cell lineages, each with different biological activities. The endovascular trophoblast phenotype invades the maternal spiral arterioles during the first trimester and replaces the smooth muscle normally present in these arteries with a non-contractile matrix. The physiological result of this normal but seemingly destructive event is a high flow, low resistance vascular conduit available to perfuse the intervillous space. Because maternal blood flow through these vessels is limited by the plugs of endovascular trophoblast in early gestation, human placental development during the first ten weeks of gestation occurs in a low oxygen environment with a PO2 measured at < 15 mmHg (Jauniaux et al. 2003). This low oxygen state transitions beyond 10 weeks’ gestation so that the developing villous tree of the chorioallantoic placenta becomes bathed with oxygenated maternal blood from the modified spiral arterioles, raising the PO2 to about 60 mmHg. Absence of endovascular trophoblast invasion of myometrial segments of the spiral arterioles, characteristic of IUGR, avails a high resistance vasculature with a persistent smooth muscle histology in the maternal spiral arterioles. This lack of transformation predisposes to hypoperfusion, hypoxia, re-perfusion injury, oxidative stress and, ultimately, to signs of villous tree maldevelopment in the second half of the pregnancy, all factors associated with IUGR.

How does the villous structure affect placental function?

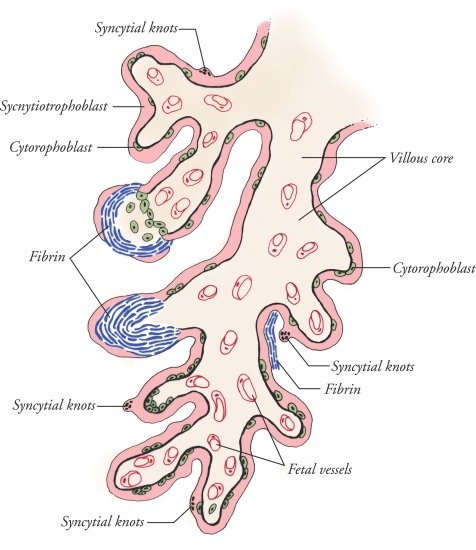

The human placenta is haemochorial in structure, with maternal blood directly bathing the trophectoderm derived trophoblast phenotype that is on the surface of the tree-like villi comprising the chorioallantoic placenta (Huppertz, 2008). The terminally differentiated syncytiotrophoblast lines the maternal blood containing intervillous space, normally as an uninterrupted cytoplasmic mass that covers the surface of all villous trees and that contains multiple nuclei non-uniformly distributed within the syncytium without lateral plasma membranes (Fig. 1). This unique syncytium is formed from fusion of subjacent, mitotically active mononucleated cytotrophoblasts that differentiate and undergo membrane–membrane fusion, adding to the overlying syncytiotrophoblast. The anatomical integrity of the syncytiotrophoblast is critical, as a variety of transporters, receptors and enzymes are strategically positioned on the maternal blood facing microvillous plasma membrane, the basal plasma membrane facing the villous core, or both to regulate maternal–fetal exchange (Jones et al. 2007). The endothelial nature of the surfacing syncytiotrophoblast also allows directional secretion of hormones, growth factors and cytokines into maternal blood to influence substrate supply and fetal growth. In addition, the syncytiotrophoblast secretes nitric oxide synthase (Sladek et al. 1997) and functions as the first line of defence against pathogens. The villous trophoblast bi-layer shares a basement membrane that delimits a villous core, which contains a fetal vessel arcade coursing through a connective tissue matrix (Huppertz, 2008). Whereas placental function is critical at all stages of pregnancy, nutrient transport demands on chorioallantoic villi in general, and villous trophoblasts in particular, are highest as the fetus triples in weight during the third trimester of gestation. This said, apoptosis of villous trophoblasts increases as pregnancy progresses (Smith et al. 1997b), and insults that yield villous injury may not be accompanied by a compensatory increase in cytotrophoblast proliferation and differentiation (Crocker et al. 2004; Heazell et al. 2008). Imbalances of injury and repair and maldevelopment of the villous tree are characteristic of the placenta in IUGR. This predisposes to depletion of syncytiotrophoblast with a consequent limitation on regulated transport and secretory functions (Redline, 2008).

Figure 1. Cartoon of a human term villus that demonstrates fibrin containing fibrinoid (blue) deposits that occur on the surface of villi in all placentas, but with increased frequency in placentas from pregnancies complicated by IUGR.

These sites of injury, and repair, appear at discontinuities of the syncytiotrophoblast, and the fibrin matrix serves as a scaffold for trophoblast to re-epithelialize the villous surface. As illustrated, plane of section yields a variable epithelial covering in any given specimen. Syncytial knots are clusters of apoptotic syncytial nuclei that bulge from the surface into the intervillous space. The subjacent cytotrophoblast population provides a source for new syncytium during normal epithelial turnover and at sites of syncytial re-epithelialization of fibrin on the surface of villi.

How do cell death pathways contribute to the turnover of villous trophoblasts?

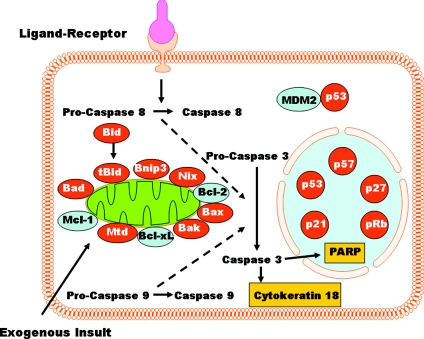

The molecular pathways to death (Fig. 2) for syncytiotrophoblasts are only partially understood, as the morphological manifestations of apoptosis in human placental villi were only recently verified (Nelson, 1996; Smith et al. 1997b). Interestingly, apoptosis is proposed as a normal part of villous trophoblast turnover and syncytiotrophoblast formation from cytotrophoblast. Indeed, the cytotrophoblast that differentiates for fusion with the syncytium exhibits multiple markers expressed by cells undergoing apoptosis (Kaufmann et al. 1987; Huppertz et al. 1998, 2006; Benirschke et al. 2006). For example, surface phosphatidylserine and activation of caspase 8 associate with cytotrophoblasts as they fuse to form more syncytiotrophoblast although the expression of phosphatidylserine may occur through apoptosis-independent pathways (Das et al. 2004). Moreover, cleavage of internucleosomal sites on DNA coincides with cytotrophoblasts destined for fusion (Huppertz & Kingdom, 2004). Condensed chromatin in the nucleus is one of the characteristic features of syncytiotrophoblast, and a variable proportion of these nuclei aggregate into clusters called syncytial knots, which exhibit the pathognomonic morphology of apoptosis as they protrude into the intervillous space (Kerr et al. 1972; Mayhew et al. 1999) (Fig. 1). Collectively, these findings have been interpreted to indicate that apoptosis and differentiation occur as a continuum during the turnover of the villous trophoblast bi-layer (Huppertz & Kingdom, 2004).

Figure 2. Overview of apoptosis.

Ligand-receptor and exogenous pathways converge downstream to activate caspases that dismantle cell organelles in both the cytoplasm (e.g. cytokeratin 18 filaments) and nucleus (e.g. poly-ADP-ribose polymerase, PARP). Signalling molecules known to be dysregulated in IUGR are discussed in the text.

Does dysregulated apoptosis yield placental dysfunction in IUGR?

Villous cytotrophoblasts from placentas of pregnancies with IUGR exhibit enhanced sensitivity to undergo cell death in response to both hypoxia and cytokines when compared to isolates from control pregnancies with average for gestational age fetuses (Ishihara et al. 2002; Athapathu et al. 2003; Crocker et al. 2003). Apoptosis is regulated at many levels. Cultured trophoblasts exposed to hypoxia show a marked up-regulation of p53 activity (Levy et al. 2000; Heazell et al. 2008), enhanced expression of the pro-apoptotic Mtd-1 (Soleymanlou et al. 2005, 2007), and decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, all of which promote apoptosis (Levy et al. 2000; Soleymanlou et al. 2005) (Fig. 2). In contrast to hypoxia alone (Levy et al. 2000), hypoxia/re-oxygenation yields even more marked apoptosis (Hung et al. 2002) regulated by other proteins such as the increased expression of the pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak (Hung et al. 2008). Mtd expression, increased in severe early-onset pre-eclampsia, is localized to syncytial knots (Soleymanlou et al. 2005) and thereby suggests a role in the regulation of these villous features. Whether or not Mtd is also overexpressed in IUGR without preeclampsia remains to be determined. In contrast, p53 expression is known to be up regulated in villi from IUGR compared to controls, and the increase is predominantly in the villous trophoblast histologically (Levy et al. 2002; Endo et al. 2005) Collectively, the in vitro and in vivo data support a key role for p53 in the regulation of apoptosis in trophoblasts from IUGR.

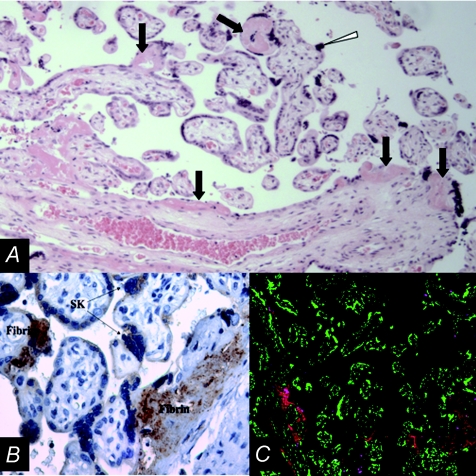

As true syncytial knots reflect a characteristic feature of syncytiotrophoblast apoptosis, one sign of an overall increase in apoptosis in placentas from pregnancies with IUGR is the prominence of syncytial knots compared to the normal villous histology of control pregnancies (Levy et al. 2002). Higher than normal levels of apoptosis in villi from IUGR is also reflected by expression of cleavage products of caspase (Smith et al. 1997a; Leung et al. 2001; Ishihara et al. 2002; Levy et al. 2002). For example, cleavage of cytokeratin 18 intermediate filaments is a prominent feature in villi from IUGR (Austgulen et al. 2004). Interestingly, cytokeratin 18 cleavage products and nuclei with totally condensed chromatin, serving as markers of apoptosis on the villous surface, are especially apparent where there is a breach in the integrity of the syncytiotrophoblast. The apparent discontinuity in the syncytium is marked by fibrin containing fibrinoid deposits (Figs 1 and 3). This fibrin deposition is noted on the trophoblastic basement membrane ultrastructurally, and the lesion thereby identifies microscopic sites of epithelial injury to villi, not visually apparent fibrin lesions that are frequently described in placentas of pathological pregnancies (Nelson et al. 1990; Nelson, 1996). Importantly, other areas of fibrin type fibrinoid reflect ongoing repair of these breaches of epithelial integrity. This repair component is apparent by immunohistochemistry as re-epithelialization by cytokeratin positive trophoblast and by ultrastructure, as unique syncytiotrophoblasts that exhibit a lateral plasma membrane extending as a tongue of syncytium over the villous surface using the fibrin matrix as a scaffold (Nelson et al. 1990). Excess injury of the villous trophoblast layer as described here would reduce the functional mass of syncytiotrophoblast in IUGR and limit the capacity of villi to mediate nutrient transport. Moreover, the microscopic injury has functional effects on placental permeability, as α-fetoprotein and small molecular weight compounds are able to pass between the maternal and fetal circulations without mediation of the syncytiotrophoblast cytoplasm (Brownbill et al. 1995, 2000). In response to, or independent of, epithelial injury, an alteration in the normal balance of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis during the villous trophoblast life cycle would also limit the functional mass of trophoblast surfacing villi. Consistent with this premise, cytotrophoblasts from placentas of IUGR do not exhibit a compensatory increase in proliferation, despite the apparent enhanced apoptotic turnover of the trophoblast layer (Crocker et al. 2003; Heazell & Crocker, 2008).

Figure 3.

A, haematoxylin and eosin staining of a cross section of villi from a placenta of a pregnancy with IUGR. Black arrows point to some of the fibrin containing fibrinoid deposits on the surface of villi where there is often a visible discontinuity in the syncytiotrophoblast layer. The white arrowhead identifies a syncytial knot bulging into the intervillous space, the latter previously containing maternal blood prior to fixation. The white arrow indicates a cluster of syncytiotrophoblast nuclei with condensed chromatin. B, cross-section of villi, at higher magnification than in A, with the fibrin containing fibrinoid deposits on the surface of villi showing peroxidase (brown staining) immunolocalization of the C5b-9 membrane attack complex of the complement cascade. C, low magnification cross-section of villi from a placenta of an IUGR pregnancy immunofluorescently stained for nuclei (green) and fibrin-containing fibrinoid deposits (red). Red fluorescence is apparent on multiple villi, marking sites of villous surface injury.

What insults contribute to the histopathology of placental injury in IUGR?

A diverse number of stimuli and mediators are likely to contribute to the observed injury to the chorioallantoic villi but oxidative stress is high on the list as an injurious agent (Hung et al. 2002). One source for oxidative stress is ischaemia/re-perfusion of the placenta by the inadequately developed spiral arterioles. The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during oxidative stress is linked with tissue injury in many diseases (Ryter et al. 2007), and trophoblast damage is induced more by hypoxia/reoxygenation than hypoxia alone (Schachter & Foulds, 1999; Hung & Burton, 2006). A recent landmark paper shows that the placentas of pregnancies with IUGR exhibit overt signs of oxidative stress, with reduced protein translation and particular reductions in key signalling proteins including those in the AKT and mTOR pathways (Yung et al. 2008). Moreover, the syncytiotrophoblast shows signs of ER stress by activating the unfolded protein response, which leads to an ER signal for enhanced apoptosis. The identified dysregulation of protein translation, signalling pathways and trophoblast turnover provide important insights into some of the mechanisms by which oxidative stress induces the dysfunction that occurs in placentas of pregnancies with IUGR (Burton et al. 2009).

Hypoxia, ischaemia/reperfusion, or both may contribute to placental injury through mechanisms other than ROS generation, as variable blood flow to organs also activates the complement cascade (Levy et al. 2000; Hung et al. 2002; Heazell et al. 2008). Dysregulated complement activation in non-pregnant patients mediates immunological injury in heart, lung and kidney, and recent data indicate that the complement cascade also plays an important role in normal and abnormal human pregnancy (Xu et al. 2000). For example, the hypoperfused kidney of women with pre-eclampsia exhibits deposition of complement split products in glomeruli and the anticardiolipin antibody syndrome that manifests in pregnancy is likely to result from activation of the complement cascade to injure the feto-placental unit (Girardi et al. 2003).

We (Rampersad et al. 2008) recently found that the C5b-9 membrane attack complex (MAC) co-localizes to the above described fibrin containing fibrinoid deposits that mark sites of injury and associate with apoptosis (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the number of fibrin deposits that co-localize with MAC is markedly higher in IUGR compared to controls (Fig. 3C). Important to the biology of villous trophoblast, MAC binds to cultured trophoblasts and modulates both apoptosis and differentiation in the process (Rampersad et al. 2008). Clarifying the role of complement activation in pregnancies complicated by IUGR, and in placental dysfunction generally, may lead to new approaches to treatment for IUGR, as therapeutic options to modulate complement receptors and complement activity are on the horizon.

Conclusions

Optimal placental development and the compensatory responses of the placenta to exogenous insults are central in promotion of a normal pregnancy. Histopathological studies of the placenta in IUGR indicate that abnormalities of the maternal spiral arterioles, dysregulated villous vasculogenesis, and abundant fibrin deposition are characteristic in IUGR (Redline, 2008). Whether these changes derive from hypoxia, ischaemia/reperfusion, complement activation, or another source, the trophoblast layer of villi reflects excess epithelial injury and ER stress that yield dysregulation at a subcellular level. The increasing gradations of placental dysfunction that evolve in a pregnancy, as the diagnosis of IUGR evolves as a consequence, ultimately results in limited nutrient transfer and reduced blood flow to the fetus (Baschat, 2004). Knowing that delivery of a suboptimally grown and often preterm baby, with a guarded short term and long term prognosis, is the end result of IUGR, investigators should be stimulated to aggressively identify the mechanisms of this disorder so that targeted therapeutic options can be developed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH HD 29190.

References

- Athapathu H, Jayawardana MA, et al. A study of the incidence of apoptosis in the human placental cells in the last weeks of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:515–517. doi: 10.1080/0144361031000153756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austgulen R, Isaksen CV, et al. Pre-eclampsia: associated with increased syncytial apoptosis when the infant is small-for-gestational-age. J Reprod Immunol. 2004;61:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschat AA. Fetal responses to placental insufficiency: an update. BJOG. 2004;111:1031–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschat AA, Gembruch U, et al. Relationship between arterial and venous Doppler and perinatal outcome in fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:407–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschat AA, Guclu S, et al. Venous Doppler in the prediction of acid-base status of growth-restricted fetuses with elevated placental blood flow resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P, Baergen R. Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IM, Horbar JD, et al. Morbidity and mortality among very-low-birth-weight neonates with intrauterine growth restriction. The Vermont Oxford Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:198–206. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownbill P, Edwards D, et al. Mechanisms of alphafetoprotein transfer in the perfused human placental cotyledon from uncomplicated pregnancy. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2220–2226. doi: 10.1172/JCI118277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownbill P, Mahendran D, et al. Denudations as paracellular routes for alphafetoprotein and creatinine across the human syncytiotrophoblast. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R677–683. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G, Yung HW, Cindrova-Davies T, Charnock-Jones DS. Placental endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of unexplained intrauterine growth restriction and early onset preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;23(Suppl A):S43–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker IP, Cooper S, et al. Differences in apoptotic susceptibility of cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in normal pregnancy to those complicated with preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:637–643. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63857-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker IP, Tansinda DM, et al. Altered cell kinetics in cultured placental villous explants in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. J Pathol. 2004;204:11–18. doi: 10.1002/path.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Xu B, et al. Phosphatidylserine efflux and intercellular fusion in a BeWo model of human villous cytotrophoblast. Placenta. 2004;25:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H, Okamoto A, et al. Frequent apoptosis in placental villi from pregnancies complicated with intrauterine growth restriction and without maternal symptoms. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardosi J, Chang A, et al. Customised antenatal growth charts. Lancet. 1992;339:283–287. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi G, Berman J, et al. Complement C5a receptors and neutrophils mediate fetal injury in the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1644–1654. doi: 10.1172/JCI18817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heazell AE, Crocker IP. Live and let die – regulation of villous trophoblast apoptosis in normal and abnormal pregnancies. Placenta. 2008;29:772–783. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heazell AE, Lacey HA, et al. Effects of oxygen on cell turnover and expression of regulators of apoptosis in human placental trophoblast. Placenta. 2008;29:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TH, Burton GJ. Hypoxia and reoxygenation: a possible mechanism for placental oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45:189–200. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TH, Chen SF, et al. Bax, Bak and mitochondrial oxidants are involved in hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in human placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:565–583. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TH, Skepper JN, et al. Hypoxia-reoxygenation: a potent inducer of apoptotic changes in the human placenta and possible etiological factor in preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2002;90:1274–1281. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024411.22110.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B. The anatomy of the normal placenta. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1296–1302. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.055277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B, Frank HG, et al. Villous cytotrophoblast regulation of the syncytial apoptotic cascade in the human placenta. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;110:495–508. doi: 10.1007/s004180050311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B, Kadyrov M, et al. Apoptosis and its role in the trophoblast. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B, Kingdom JC. Apoptosis in the trophoblast–role of apoptosis in placental morphogenesis. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Matsuo H, et al. Increased apoptosis in the syncytiotrophoblast in human term placentas complicated by either preeclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:158–166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, et al. The human first trimester gestational sac limits rather than facilitates oxygen transfer to the foetus – a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl A):S86–93. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HN, Powell TL, et al. Regulation of placental nutrient transport – a review. Placenta. 2007;28:763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Luckhardt M, et al. Cross-sectional features and three-dimensional structure of human placental villi. Placenta. 1987;8:235–247. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(87)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, et al. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DN, Smith SC, et al. Increased placental apoptosis in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1249–1250. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.112906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Smith SD, et al. Apoptosis in human cultured trophoblasts is enhanced by hypoxia and diminished by epidermal growth factor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C982–988. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.5.C982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Smith SD, et al. Trophoblast apoptosis from pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction is associated with enhanced p53 expression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1056–1061. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew TM, Leach L, et al. Proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis in villous trophoblast at 13–41 weeks of gestation (including observations on annulate lamellae and nuclear pore complexes) Placenta. 1999;20:407–422. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire DD, Bloom SL, et al. Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1234–1238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Turan S, et al. Fetal growth restriction. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:274–280. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy VE, Smith R, et al. Endocrine regulation of human fetal growth: the role of the mother, placenta, and fetus. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:141–169. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DM. Apoptotic changes occur in syncytiotrophoblast of human placental villi where fibrin type fibrinoid is deposited at discontinuities in the villous trophoblast. Placenta. 1996;17:387–391. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DM, Crouch EC, et al. Trophoblast interaction with fibrin matrix. Epithelialization of perivillous fibrin deposits as a mechanism for villous repair in the human placenta. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:855–865. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampersad R, Barton A, et al. The C5b-9 membrane attack complex of complement activation localizes to villous trophoblast injury in vivo and modulates human trophoblast function in vitro. Placenta. 2008;29:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline RW. Placental pathology: a systematic approach with clinical correlations. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigano S, Bozzo M, et al. Early and persistent reduction in umbilical vein blood flow in the growth-restricted fetus: a longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:834–838. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo G, Capponi A, et al. Doppler indices from inferior vena cava and ductus venosus in predicting pH and oxygen tension in umbilical blood at cordocentesis in growth-retarded fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:401–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1996.07060401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Kim HP, et al. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:49–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter M, Foulds S. Free Radicals and the Xanthine Oxidase Pathway. London: Blackwell Science; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sladek SM, Magness RR, et al. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;272:R441–463. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SC, Baker PN, et al. Increased placental apoptosis in intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997a;177:1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SC, Baker PN, et al. Placental apoptosis in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997b;177:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleymanlou N, Jurisicova A, et al. Hypoxic switch in mitochondrial myeloid cell leukemia factor-1/Mtd apoptotic rheostat contributes to human trophoblast cell death in preeclampsia. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:496–506. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleymanlou N, Wu Y, et al. A novel Mtd splice isoform is responsible for trophoblast cell death in pre-eclampsia. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:441–452. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Mao D, et al. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000;287:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung HW, Calabrese S, et al. Evidence of placental translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the etiology of human intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:451–462. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]