Abstract

Muscle protein synthesis is increased after exercise, but evidence is now accruing that during muscular activity it is suppressed. In life, muscles are subjected to shortening forces due to contraction, but may also be subject to stretching forces during lengthening. It would be biologically inefficient if contraction and stretch have different effects on muscle protein turnover, but little is known about the metabolic effects of stretch. To investigate this, we assessed myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein synthesis (MPS, SPS, respectively) by incorporation of [1-13C]proline (using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry) and anabolic signalling (by phospho-immunoblotting and kinase assays) in cultured L6 skeletal muscle cells during 30 min of cyclic stretch and over 30 min intervals for up to 120 min afterwards. SPS was unaffected, whereas MPS was suppressed by 40 ± 0.03% during stretch, before returning to basal rates by 90–20 min afterwards. Paradoxically, stretch stimulated anabolic signalling with peak values after 2–30 min: e.g. focal adhesion kinase (FAK Tyr576/577; +28 ± 6%), protein kinase B activity (Akt; +113 ± 31%), p70S6K1 (ribosomal S6 kinase Thr389; 25 ± 5%), 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1 Thr37/46; 14 ± 3%), eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2 Thr56; −47 ± 4%), extracellular regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2 Tyr202/204; +65%± 9%), eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α Ser51; −20 ± 5%, P < 0.05) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E Ser209; +33 ± 10%, P < 0.05). After stretch, except for Akt activity, stimulatory phosphorylations were sustained: e.g. FAK (+26 ± 11%) for ≥30 min, eEF2 for ≥60 min (peak −45 ± 4%), 4EBP1 for ≥90 min (+33 ± 5%), and p70S6K1 remained elevated throughout (peak +64 ± 7%). Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation was unchanged throughout. We report for the first time that acute cyclic stretch specifically suppresses MPS, despite increases in activity/phosphorylation of elements thought to increase anabolism.

Muscle protein synthesis is modulated as a result of mechanical activity: during strenuous muscular activity protein synthesis is suppressed (Bylund-Fellenius et al. 1984; Miranda et al. 2008) but increases afterwards, resulting in a net increase of protein if sufficient amino acids are available (Rennie & Tipton, 2000). The underlying mechanisms resulting in these changes are poorly understood but are likely to include differential regulation of the initiation and elongation phases of protein translation (Kumar et al. 2009b).

What regulates the different responses during and after exercise is poorly understood. During muscular activity, increases in sarcoplasmic Ca2+ transients result in a rapid stimulation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase eEF2K activity, which induces phosphorylation and inhibition of eEF2 polypeptidyl-tRNA translocase activity (Rose et al. 2005). Also during contraction, in a slower process AMPK is activated (Rose et al. 2009) probably due to contraction-induced increases in the ratios [AMP]:[ATP] and [Cr]:[PCr], which results in suppressed signalling activity of mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1) (Bolster et al. 2002), and eventually initiation and elongation phases of protein translation; but this appears to be less important than the Ca2+ mediated inhibition (Rose et al. 2009). The result is a marked inhibition of protein synthesis. After exercise, the rebound of MPS is associated with upregulated anabolic signalling through the classic ‘anabolic’ signalling cascade (PKB/Akt–mTORC1) (Atherton et al. 2005; Kumar et al. 2009a). Underlying the anabolic rebound are normalized Ca2+ and phosphagen homeostasis, restored Akt–mTORC1 signalling, increases in nutrient availability and, possibly, autocrine and paracrine growth factors.

There is limited understanding of the critical molecular events underlying the integration of mechanical signals toward downstream muscle protein synthesis responses. It has been postulated that the proximal mechanisms underlying anabolic signalling may include mechanosensitive signalling complex(es) contained within costameres. For example, the activity of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a mechano-responsive kinase localized to focal adhesions (Durieux et al. 2007), is robustly increased by loading (i.e. stretching) in animal muscles (Fluck et al. 1999) and decreased by unloading in human muscle (de Boer et al. 2007; Glover et al. 2008). Furthermore, phosphotransferase activity of FAK induces Akt and tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) thereby stimulating mTORC1 signalling and promoting MPS (Martin & Hwa, 2008). Nevertheless, whether FAK regulates acute muscle protein synthesis responses to stretch remains to be investigated.

Besides the force-producing effects of muscular contraction, muscles in life are subjected to substantial forces induced by lengthening of muscles, either due to the action of antagonistic muscles but also the result of so called ‘eccentric contractions’ when muscles are supporting a weight as it is lowered or in running down hill. However, the effects of such actions on protein metabolism are poorly understood. Some of us previously demonstrated a more rapid rise in post-exercise MPS after lengthening than shortening contractions (Moore et al. 2005) suggesting that with exercise the responses in MPS are probably due to a combination of both contraction and stretch stimuli, the relative contributions of which cannot be easily ascertained with physiological exercise bouts. The only report of an attempt to induce a change in human muscle protein synthesis after stretch demonstrated no effect (Fowles et al. 2000), although this measure was made 10–22 h after stretch at which time any short-lived effects of stretch could not be determined. To fill this gap, we investigated the effects on muscle protein synthesis and anabolic signalling both during and immediately after stretch. Because it would make little sense functionally for any stretch-mediated anabolic responses to counter the inhibition of muscle protein synthesis due at least in part to Ca2+ influx during contraction, we hypothesized that muscle protein synthesis will be inhibited during stretch and increased afterwards, with cognate changes in FAK phosphorylation and anabolic signalling.

Methods

Cell culture and stretch conditions

L6 skeletal myoblasts were seeded and proliferated on type I collagen coated Bio-flex six-well Flexecell plates (Flexcell International Corp., Hillsborough, NC, USA) in Dulbeco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) incorporating 10% fetal bovine serum, amphoteracin B (1%), and penstreptomycin (1%) (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and induced to differentiate at ∼80% confluency of myoblasts into multinucleated branching myotubes by reducing serum concentrations to 2% for ∼7–9 days. Experiments were carried out 24 h after a change of medium to eliminate the effects of acute responses to sera; DMEM contains physiologically high amino acid concentrations (i.e. 800 μm leucine), which ensured substrate was not a limiting factor in synthetic responses. At least 1 h before experiments, six-well plates (including control, non-stretched cells) were placed on the Flexercell FX4000T (Flexcell International). The Flexercell Tension Plus is a vacuum operated system that provides a uniform radial and circumferential strain to cells cultured on a flexible membrane. All cells (n= 6 replicates per condition) were cyclically stretched under standard incubator conditions (37°C, 95% O2–5% O2) using a 15% 1 Hz sine wave for 30 min except for non-stretched controls and cells stretched for 2 and 15 min to assess anabolic signalling ‘during stretch’ (technical reasons forbade measures of protein synthesis over these short periods). Our overall sampling protocol was 2, 15 and 30 min (representative of events ‘during stretch’) and 60, 90, 120 and 150 min (representative of events after stretch). Protein synthesis was measured by addition of [1-13C]proline (Cambridge Isotopes, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 45 atoms % to raise its concentration to 1 mm). After each period, the medium was removed for measurement of free [13C]proline labelling, taken to represent the precursor labelling for protein synthesis, given that the large amount of labelled proline would have flooded all free pools. The cells were immediately washed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), scraped and harvested for measurement of [13C]proline incorporation into protein and for immunoblotting. Examination of cultured myotubes by light microscopy indicated that cell morphology did not change as a result of mechanical stimulation.

Myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein synthesis

Cells were homogenised by repeated pipetting using gel-loading tips in ice-cold extraction buffer containing 50 mm Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mmβ-glycerophosphate, 50 mm NaF, 0.5 mm activated sodium orthovanadate (all Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK) and a complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, West Sussex, UK). The homogenate was rotated on a Vibramax for 10 min at 4°C and then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min. A portion (∼200 μg protein) of supernatants (sarcoplasmic fractions) was removed for immunoblotting and kinase activity assays before the remaining sarcoplasmic fractions and myofibrillar pellets were solubilized in 0.3 n NaOH at 37°C for 20 min then precipitated using 1 m perchloric acid and the pellet washed twice with 70% ethanol. Proteins were hydrolysed in 0.05 m HCl/Dowex 50W-X8-200 at 110°C overnight, and the liberated amino acids purified then eluted in 2 m NH4OH. The amino acids were subsequently derivatized as their N-acetyl-n-propyl ester. The proline incorporation was analysed by capillary gas chromatography–combustion–mass spectrometry (Delta-plus XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK); separation was achieved on a 25 m × 0.25 mm × 1.0 μm film DB 1701 capillary column (Agilent Technologies, West Lothian, UK). Free proline labelling in the medium was determined after precipitation of protein with 100% ice-cold ethanol, evaporation of the supernatant and subsequent derivatisation as its tert-butyldimethylsilyl (by gas-chromatography–mass spectrometry (MD800, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using our standard techniques (Babraj et al. 2005); separation was achieved using a 25 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film EC-1 (Alltech Associate, Carnforth, UK). Protein synthesis was calculated as the fractional synthetic rate (FSR), i.e. [(Einc/Emedium) ×t−1]× 100, where Einc is the enrichment of protein bound proline, Emedium is the enrichment of free proline in the medium and t is the time; FSR is expressed per hour.

Immunoblotting and kinase assays

Phosphorylated protein concentrations were determined of eEF2 Thr56, mTOR Ser2448, p70S6K Thr389, 4EBP1 Thr37/46, AMPK Thr172, FAK Tyr576/577, ERK1/2 MAPK Tyr202/204, GSK3β Ser21/9, eIF4E Ser209, eIF2Bα Ser51 (New England Biolabs, UK), and α-actin (loading control; Sigma Aldrich, Poole, UK). To assess purity of the fractionation, we also measured relative concentrations of, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), histone H3 and cytochrome c (New England Biolabs) and myosin (Sigma Aldrich). A Bradford assay was used to quantify protein concentrations of 10 000 g supernatants. For kinase activity, Akt was immunoprecipitated from 100 μg proteins before incubation with 1 mm ATP and GSK3β Ser21/9 fusion protein substrate (New England Biolabs). Twenty micrograms of each protein sample (or 15 μl of kinase reactions) was loaded on to Criterion XT Bis-Tris 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK) for electrophoresis at 150 V for ∼75 min and electroblotted to 0.2 μm PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). After incubation for 1 h with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T; both Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK), membranes were rotated overnight with primary antibody against the aforementioned targets at a concentration of 1 : 2000 at 4°C. Membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (New England Biolabs, UK), before further washing with TBS-T and incubation for 5 min with ECL reagents (enhanced chemiluminescence kit, Immunstar; Bio-Rad). Blots were imaged and quantified by assessing peak density within the linear range of detection using the Chemidoc XRS system (Bio-Rad).

Statistics

Phosphorylation of signalling proteins was corrected for loading anomalies to α-actin. Statistically significant differences were assessed by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc testing (GraphPad Prism v5.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) to locate statistically significant differences at P < 0.05. Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

Results

Fractionation of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic proteins

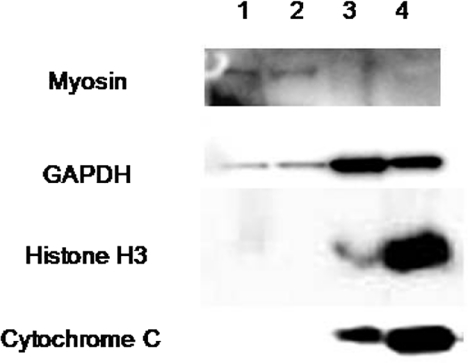

Our crude fractionation procedure was assessed by immunoblotting for myosin (myofibrilar), GAPDH (myoplasmic), histone H3 (nuclear) and cytochrome c (mitochondrial). The blots in Fig. 1 demonstrate that our myofibrillar fractions were myosin positive but mainly negative for markers of other compartments. Conversely, our sarcoplasmic fractions were negative for myosin but positive for markers of all other assayed compartments indicating that the presence of detergent coupled to the shear forces created by our repeated pipetting/lysis method of homogenisation resulted in the clean distinction of cytosolic and membrane proteins from the myofibrillar pellet. Thus our myofibrillar fraction was not substantially contaminated by other organelles.

Figure 1. Immunoblots representing qualitative compositions of crude moyofibrillar and sarcoplasmic fractions.

Lanes 1 and 2 are myofibrillar and lanes 3 and 4 sarcoplasmic fractions.

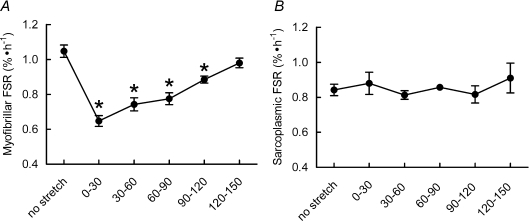

MPS, but not SPS, is regulated by acute cyclic stretch

To examine the potential role of acute cyclic stretch on muscle protein synthesis, we examined synthetic rates in myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic fractions during and after an acute bout of cyclic stretch. Cyclic stretch suppressed MPS by 40 ± 0.03% (P < 0.01) over 30 min (see Fig. 2A), and rates remained significantly suppressed until 120–150 min when they were not different from those of unstretched cells. In contrast, SPS rates were not affected by stretch at any time (see Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Effect of cyclic stretch on myofibrillar (A) and sarcoplasmic (B) FSR in L6 myotubes.

Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. (n= 6 replicates per condition). *Different from no stretch conditions, P < 0.05.

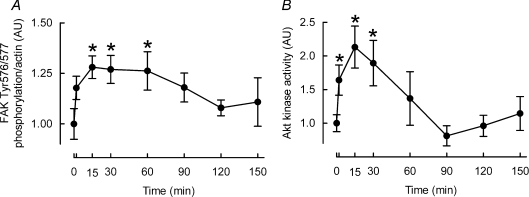

FAK phosphorylation correlates with Akt activity during stretch

Since FAK is considered to be mechano-sensitive, and a putative regulator of Akt signalling, we investigated if there was a correlation between FAK phosphorylation and Akt kinase activity. In support of this, both phosphorylation of FAK Tyr576/577 (peak ∼28%± 6%P < 0.05; see Fig. 3A), and kinase activity of Akt (peak 113 ± 31%P < 0.01; see Fig. 3B) were increased at 15 and 30 min.

Figure 3. Effects of cyclic stretch on FAK phosphorylation (A) and Akt kinase activity (B) in L6 myotubes.

Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) as means ±s.e.m. (n= 6 replicates per condition). *Different from time 0, P < 0.05.

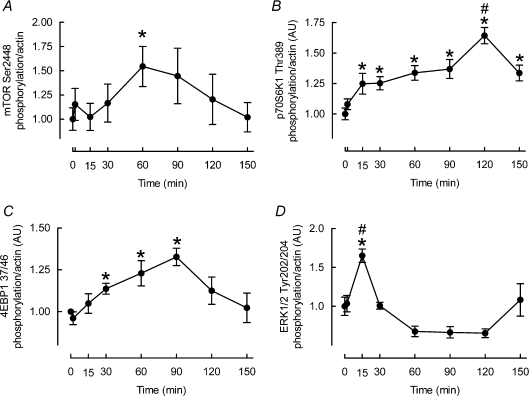

mTORC1 signalling and ERK1/2 phosphorylation are paradoxically increased during stretch

We next investigated whether mTORC1 signalling could explain a suppression of MPS. On the contrary, although mTOR Ser2448 phosphorylation was not significantly increased during stretch (see Fig. 4A), of the two key mTORC1 substrates, phosphorylation of p70S6K1 Thr389 was increased at 15 and 30 min (peak 25 ± 5%P < 0.05; see Fig. 4B) and phosphorylation of 4EBP1 Thr37/46 was stimulated by 30 min (14 ± 3%P < 0.05; see Fig. 4C). To investigate the possibility of MAPK-dependent suppression of protein synthesis we measured ERK1/2 Tyr202/204 phosphorylation, but conversely observed that it was increased by 15 min (65%± 9%P < 0.01; see Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Effects of cyclic stretch on mTOR (A), p70S6K1 (B), 4EBP1 (C) and ERK1/2 (D) phosphorylation in L6 myotubes.

Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) as means ±s.e.m. (n= 6 replicates per condition). *Different from time 0, P < 0.05; #different from all other times, P < 0.05.

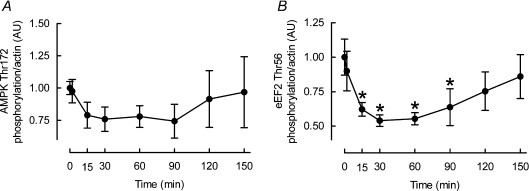

Inhibitory activation of AMPK and eEF2 do not explain suppression of MPS

Two mechanisms proposed to inhibit protein synthesis during muscular activity are AMPK activation as a consequence of increased ratios of [AMP]:[ATP] and [Cr]:[PCr] and eEF2K activation as a result of rises in Ca2+. In contrast to our hypothesis, AMPK was unchanged throughout (see Fig. 5A), whereas eEF2 Thr56 phosphorylation was depressed (indicating activation) at 15 and 30 min (peak −47 ± 4%, P < 0.05; see Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Effects of cyclic stretch on AMPK (A) and eEF2 (B) phosphorylation in L6 myotubes.

Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) as means ±s.e.m. (n= 6 replicates per condition). *Different from time 0, P < 0.05.

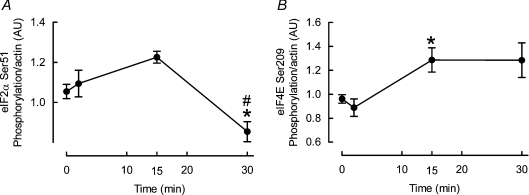

Inhibitory phosphorylations on eIF2α and eIF4E do not explain suppression of MPS

To search for other explanations we measured phosphorylation of eIF2α and eIF4E, which are often overlooked in studies of muscle protein synthesis regulation but regulate key steps in initiation. Nonetheless, again we found that phosphorylations of eIF2α at 30 min (−20 ± 5%, P < 0.05; see Fig. 6A) and eIF4E at 15 min (+33 ± 10%, P < 0.05; see Fig. 6B) favoured increases in protein synthesis.

Figure 6. Effects of cyclic stretch on eIF2α (A) and eIF4E (B) phosphorylation in L6 myotubes.

Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) as means ±s.e.m. (n= 6 replicates per condition). *Different from time 0, P < 0.05; #different from all other times, P < 0.05.

Anabolic signalling is sustained post-stretch

Phosphorylation of mTOR Ser2448 was increased by 60 min (+55 ± 20%, P < 0.05) and with Akt as the exception, all other anabolic signalling was sustained: FAK for 30 min (+26 ± 11%, P < 0.05), eEF2 for 60 min (peak −45 ± 4%, P < 0.05), 4EBP1 for 90 min (peak +33 ± 5%, P < 0.05), and p70S6K1 throughout (peak +64 ± 7%, P < 0.01), which was thus the sole signal that remained elevated at our last measurement point 120 min post-stretch. These signals may help to explain the post-stretch increase in MPS.

Discussion

Muscle stretch is a normal component of physiological exercise (i.e. stretch of antagonistic muscles, eccentric contractions) and it has now become apparent that during contractile activity and physiological exercise, muscle protein synthesis is rapidly and profoundly suppressed (Bylund-Fellenius et al. 1984; Miranda et al. 2008). We hypothesised on teleological grounds that an acute bout of cyclic stretch should induce responses reinforcing those of contraction, i.e. an inhibition of protein synthesis.

We report for the first time that acute cyclic stretch, like contraction in vitro, suppresses MPS by ∼40% (see Fig. 2A) before gradually returning to basal rates 120–150 min after stretch. There have been few other reports on the regulation of muscle protein synthesis during acute stretch. Hornberger et al. intermittently stretched rat EDL muscles in vitro 15% above resting length every 3 s and showed that mixed muscle protein synthesis was unchanged over 0–30 and 30–60 min (Hornberger et al. 2004).

The differences in those earlier results from those we report may be broadly explained by (i) the timing of measurement, (ii) the stretch protocol used, and (iii) the proteins the synthesis of which were measured. The only human study on the topic reported that active isometric contraction but not passive stretch stimulated protein synthesis (Fowles et al. 2000). However, these measures were made 10–22 h after exercise, which although justifiable for contractile activity where responses may be sustained for >24 h (Phillips et al. 1997), does not exclude the possibility that responses to stretch were missed, nor does it reflect what is occurring during stretch. Next, we employed a stretch pattern with a greater relative time under stretch (sinusoidal wave, 0–15–0% in 1 s, frequency 1 Hz) than that used by Hornberger and colleagues (square-wave, 0–15–0% 50 ms ramp, 100 ms hold, frequency 0.33 Hz). It seems probable that, as has been shown for contraction (Rose et al. 2009), the degree of suppression in MPS is proportional to the degree of stretch. Finally, these differences may relate to the insensitivity of discerning changes in specific muscle fractions when making measurements on whole muscle as did Hornberger; in our hands despite observing a 40% reduction in MPS, we found no change in SPS (Fig. 2B), a discordance that had not been previously reported with mechanical activity. We speculate that the specific suppression of MPS by stretch is due to aspects of mechanical stress on the sarcomere that cannot be discerned when coupled to contraction, when demand for ATP to drive contraction prevails over the metabolic expenditure required for global protein synthesis (i.e. MPS and SPS).

We initially investigated whether alterations in the phosphorylation of the putative mechanosensor, FAK and other anabolic signalling molecules were cognate with the MPS responses. During stretch we found, against our hypothesis, suppressed (i.e. activated) eIF2α and eEF2 phosphorylation and increases in FAK, p70S6K1, 4EBP1 (the latter two being indices of mTORC1 activity) and eIF4E phosphorylation as well as increased Akt kinase activity (see Figs 3, 4, 5 and 6). Indeed, many of these stimulatory changes are consistent with responses that have been previously reported after a similar acute (10 min) multiaxial stretch of C2C12 skeletal muscle cells using the Flexercell apparatus (Hornberger et al. 2005). However, since protein synthesis was not measured in those studies, our findings suggest cautious interpretation of static signalling measurements in the absence of dynamic measures of protein synthesis.

Our observations that FAK and Akt activity are stimulated at 15 and 30 min of stretch supports the notion that FAK phosphorylation is acutely mechanosensitive in skeletal muscle (as had been reported in cardiomyocytes; Seko et al. 1999) and that FAK may be upstream of Akt signalling (Martin & Hwa, 2008), although further studies will be required to assess if FAK activity is required for Akt signalling. Nevertheless, changes in neither appeared to be in a direction that should (on current knowledge) lead to the observed decrease in MPS. We chose to measure ERK1/2 phosphorylation partly because there are links to mTORC1-independent regulation of protein synthesis via stimulation of MAP kinase-interacting kinases (MNK)1 and MNK2 substrates that regulate eIF4E phosphorylation (Williamson et al. 2006). However, the fact that we observed significant upregulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by 30 min stretch suggests this is not the active mechanism of the decrease in MPS.

What then could be the mechanism for the suppression of MPS? We wondered whether AMPK activation was sensitive to stretch (presumably via previously unknown mechanisms, as stretch would not be expected to increase AMP or creatine concentrations as normal contraction would) and accordingly measured AMPK Thr172 and ACCβ Ser729 phosphorylation (data not shown). However, we found no effect on indices of AMPK activation (Fig. 5A), which is consonant with a recent report that the suppression of muscle protein synthesis by contraction was not prevented in muscles from AMPKα-2 kinase-dead mutant muscles (Rose et al. 2009). We propose that our data provide further evidence that AMPK activity is not required for suppression of MPS, and perhaps global protein synthesis during physiological muscular activity.

Another mechanism associated with the suppression of protein synthesis during muscular activity is increased Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent eukaryotic initiation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K) signalling as a consequence of Ca2+ transients generated from excitation–contraction (E-C) coupling processes (Rose et al. 2005; Miranda et al. 2008). Recent work by Rose and colleagues clarified this mechanism by demonstrating that the suppression of protein synthesis by contraction was partially dependent upon Ca2+-dependent activation of eEF2K (Rose et al. 2009). However, Ca2+ influx is not specific to contraction: stretch-induced 2-deoxyglucose uptake in C2C12 myotubes is prevented by the ryanodine receptor 1 (RyR1) inhibitor dantrolene and stretch of myotubes increases Ca2+ influx via mechanically sensitive plasma membrane ion channels suggesting that both sarcoplasmic reticulum and extracellular derived Ca2+ are increased with stretch (Nakamura et al. 2001; Iwata et al. 2007). Therefore we wondered if stretch-induced Ca2+ currents could induce eEF2K activity and thereby stimulate inhibitory phosphorylation of eEF2. On the contrary, phosphorylation of eEF2 Thr56 was depressed (i.e. activated) at 15 and 30 min of stretch (see Fig. 5B) indicating inhibition, rather than activation, of the dedicated eEF2 upstream kinase, eEF2K. Therefore, our findings do not, provisionally, support a role for a Ca2+-dependent mechanism of suppressed MPS with stretch; perhaps the nature of contractile Ca2+ signalling (i.e. amplitude, frequency) is more conducive to the stimulation of eEF2K than stretch induced Ca2+ responses. Nevertheless, such negative findings are perhaps not surprising since Rose and colleagues’ recent work demonstrated that Ca2+-dependent mechanisms only account for ∼30–40% of the suppression of muscle protein synthesis by contraction (Rose et al. 2009). Clearly, further studies are required to uncover upstream signal(s) responsible for the unaccounted fraction of suppressed MPS with contraction, and those holistically with stretch. Signals such as reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (Chambers et al. 2009), stretch activated channels (Spangenburg & McBride, 2006), or alternative Ca2+-dependent mechanisms (Iwata et al. 2007) may be involved, although how these would relate to mechanisms altering MPS must be purely speculative currently.

Although increases in anabolic signalling appear to alter in a way which should negate influences contributing to suppressed MPS, there are other reports of signalling dissociation to protein synthesis in mechanical settings; for example, 30 min of isometric contractions to rat EDL muscles in vitro suppressed protein synthesis by 75% despite showing no depression (rather trends for increases) in anabolic signalling (Miranda et al. 2008). What could be the reasons for the apparent discontinuity between anabolic signalling and MPS? If regulatory anabolic signalling proteins are physically immobilized to the actin cytoskeleton (Ingber et al. 1994; Plopper et al. 1995) then changes in mechanical activity may alter their de/activation through conformational changes. Thus, we speculate that anabolic signals induced by contraction are overridden by inhibitory signals related to metabolic and Ca2+ homeostasis to a degree depending upon the intensity of the stimulus. Conversely, with stretch, an absence of inhibitory signals supports stimulation of anabolic signalling, but MPS remains suppressed as there are other as yet unknown levels of regulation.

Despite there being no net increase in MPS after acute stretch (as has been previously reported in human muscle; Fowles et al. 2000), increases in anabolic signalling were cognate with the recovery of MPS to basal rates; with sustained phosphorylations after stretch of FAK for ∼30 min, eEF2 for ∼60 min, 4EBP1 for ∼90 min, p70S6K1 throughout as well as induction of mTOR phosphorylation at 60 min. The observation that mTOR Ser2448 phosphorylation occurred later than that of p70S6K1 and 4EBP1 at rapamycin-sensitive sites suggests that Ser2448 is not representative of mTORC1 kinase activity, at least in these settings. Of the signals we found to be activated during stretch, only Akt kinase activity had returned to basal rates by the first period post-stretch, suggesting that Akt activity is not required for the perpetuation of downstream anabolic signalling in the post-stretch period. In support of this, induction of p70S6K1 phosphorylation by multiaxial stretch is not affected by wortmannin or in muscles from Akt–/– mice (Hornberger et al. 2004, 2005) suggesting a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-indepdendent pathway for downstream signalling. Consonant with its possibly unique role in regulation of protein synthesis and as a predictor of hypertrophic responses to resistance exercise training (Baar & Esser, 1999), p70S6K1 was the sole remaining anabolic signalling event 2 h after stretch. Moreover, due to the sustained response of p70S6K1 we cannot exclude the possibility that prolonging our measurement period beyond 2 h after stretch would not have led to an eventual increase in MPS.

In summary, we have shown that like contraction, acute cyclic stretch inhibits MPS despite increasing anabolic signalling. We conclude that depressed MPS during muscular activity is likely to be regulated, to some extent, independently of metabolic and recognized Ca2+-dependent mechanisms by means warranting further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank BBSRC (BB/X510697/1 and BB/C516779/1), the EC EXEGENESIS programme, NIH NIAMS (AR054342) and the University of Nottingham. P.A. is an RCUK Fellow.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 4EBP1

4E binding protein 1

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- eIF

eukaryotic initiation factor

- ERK1/2

extracellular regulated protein kinase 1/2

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- MPS

myofibrillar protein synthesis

- SPS

sarcoplasmic protein synthesis

Author's contributions

P.J.A.: conception, design, analysis, interpretation, drafting, final approval; N.J.S.: design, analysis, interpretation, critical revision, final approval; A.S.: analysis, critical revision, final approval; D.R.: analysis, critical revision, final approval; K.H.: analysis, critical revision, final approval; K.S.: analysis, interpretation, critical revision, final approval; M.J.R.: raising funds, conception, design, interpretation, critical revision, final approval; P.T.L.: design, analysis, interpretation, critical revision, final approval.

References

- Atherton PJ, Babraj J, Smith K, Singh J, Rennie MJ, Wackerhage H. Selective activation of AMPK-PGC-1α or PKB-TSC2-mTOR signaling can explain specific adaptive responses to endurance or resistance training-like electrical muscle stimulation. FASEB J. 2005;19:786–788. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2179fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baar K, Esser K. Phosphorylation of p70(S6k) correlates with increased skeletal muscle mass following resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;276:C120–C127. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babraj JA, Cuthbertson DJ, Smith K, Langberg H, Miller B, Krogsgaard MR, Kjaer M, Rennie MJ. Collagen synthesis in human musculoskeletal tissues and skin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E864–E869. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00243.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolster DR, Crozier SJ, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle through down-regulated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23977–23980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund-Fellenius AC, Ojamaa KM, Flaim KE, Li JB, Wassner SJ, Jefferson LS. Protein synthesis versus energy state in contracting muscles of perfused rat hindlimb. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1984;246:E297–E305. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.246.4.E297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers MA, Moylan JS, Smith JD, Goodyear LJ, Reid MB. Stretch-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle is mediated by reactive oxygen species and p38 MAP-Kinase. J Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165639. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, Maganaris CN, Seynnes OR, Rennie MJ, Narici MV. Time course of muscular, neural and tendinous adaptations to 23 day unilateral lower-limb suspension in young men. J Physiol. 2007;583:1079–1091. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux AC, Desplanches D, Freyssenet D, Fluck M. Mechanotransduction in striated muscle via focal adhesion kinase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1312–1313. doi: 10.1042/BST0351312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluck M, Carson JA, Gordon SE, Ziemiecki A, Booth FW. Focal adhesion proteins FAK and paxillin increase in hypertrophied skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;277:C152–C162. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles JR, MacDougall JD, Tarnopolsky MA, Sale DG, Roy BD, Yarasheski KE. The effects of acute passive stretch on muscle protein synthesis in humans. Can J Appl Physiol. 2000;25:165–180. doi: 10.1139/h00-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover EI, Phillips SM, Oates BR, Tang JE, Tarnopolsky MA, Selby A, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Immobilization induces anabolic resistance in human myofibrillar protein synthesis with low and high dose amino acid infusion. J Physiol. 2008;586:6049–6061. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger TA, Armstrong DD, Koh TJ, Burkholder TJ, Esser KA. Intracellular signaling specificity in response to uniaxial vs. multiaxial stretch: implications for mechanotransduction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C185–C194. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger TA, Stuppard R, Conley KE, Fedele MJ, Fiorotto ML, Chin ER, Esser KA. Mechanical stimuli regulate rapamycin-sensitive signalling by a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-, protein kinase B- and growth factor-independent mechanism. Biochem J. 2004;380:795–804. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE, Dike L, Hansen L, Karp S, Liley H, Maniotis A, McNamee H, Mooney D, Plopper G, Sims J, et al. Cellular tensegrity: exploring how mechanical changes in the cytoskeleton regulate cell growth, migration, and tissue pattern during morphogenesis. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;150:173–224. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata M, Hayakawa K, Murakami T, Naruse K, Kawakami K, Inoue-Miyazu M, Yuge L, Suzuki S. Uniaxial cyclic stretch-stimulated glucose transport is mediated by a Ca-dependent mechanism in cultured skeletal muscle cells. Pathobiology. 2007;74:159–168. doi: 10.1159/000103375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Selby A, Rankin D, Patel R, Atherton P, Hildebrandt W, Williams J, Smith K, Seynnes O, Hiscock N, Rennie MJ. Age-related differences in the dose–response relationship of muscle protein synthesis to resistance exercise in young and old men. J Physiol. 2009a;587:211–217. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Atherton P, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Human muscle protein synthesis and breakdown during and after exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2009b;106:2026–2039. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91481.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KA, Hwa J. Shp shape: FAKs about hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;103:776–778. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda L, Horman S, De PI, Hue L, Jensen J, Rider MH. Effects of contraction and insulin on protein synthesis, AMP-activated protein kinase and phosphorylation state of translation factors in rat skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:1129–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Phillips SM, Babraj JA, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Myofibrillar and collagen protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle in young men after maximal shortening and lengthening contractions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E1153–E1159. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00387.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TY, Iwata Y, Sampaolesi M, Hanada H, Saito N, Artman M, Coetzee WA, Shigekawa M. Stretch activated cation channels in skeletal muscle myotubes from sarcoglycan-deficient hamsters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C690–C699. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SM, Tipton KD, Aarsland A, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR. Mixed muscle protein synthesis and breakdown after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1997;273:E99–E107. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plopper GE, McNamee HP, Dike LE, Bojanowski K, Ingber DE. Convergence of integrin and growth factor receptor signaling pathways within the focal adhesion complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1349–1365. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie MJ, Tipton KD. Protein and amino acid metabolism during and after exercise and the effects of nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:457–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Broholm C, Kiillerich K, Finn SG, Proud CG, Rider MH, Richter EA, Kiens B. Exercise rapidly increases eukaryotic elongation factor 2 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of men. J Physiol. 2005;569:223–228. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Alstead TJ, Jensen TE, Kobberø JB, Maarbjerg SJ, Jensen J, Richter EA. A Ca2+-CaM-eEF2K-eEF2 signalling cascade, but not AMPK, contributes to the suppression of skeletal muscle protein synthesis during contractions. J Physiol. 2009;587:1547–1563. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seko Y, Takahashi N, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Yazaki Y. Pulsatile stretch activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family members and focal adhesion kinase (p125(FAK)) in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:8–14. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenburg EE, McBride TA. Inhibition of stretch-activated channels during eccentric muscle contraction attenuates p70S6K activation. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:129–135. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00619.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DL, Kubica N, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Exercise-induced alterations in extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling to regulatory mechanisms of mRNA translation in mouse muscle. J Physiol. 2006;573:497–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]