Abstract

This prospective, intergenerational study considered multiple influences on 102 fathers’ constructive parenting of 181 children. Fathers in the second generation (G2) were recruited as boys on the basis of neighborhood risk for delinquency and assessed through early adulthood. The fathers’ parents (G1) and the G2 mothers of G3 also participated. A multiagent, multimethod approach was used to measure G1 and G2 constructive parenting (monitoring, discipline, warmth, and involvement), G2 positive adolescent adjustment, and problem behavior in all 3 generations, including G3 difficult temperament and externalizing problems in early and middle childhood, respectively. Path modeling supported direct transmission of G1 constructive parenting of G2 in late childhood to G2 constructive parenting of G3 in middle childhood. Of note, G1 parenting indirectly influenced G2 parenting through G2 positive adjustment but not through G2 adolescent antisocial behavior. G1 parenting influenced G2 parenting in both early and middle childhood of G3. G2 parenting influenced G3 problem behavior but not vice versa. Intergenerational continuities in parenting persisted, even when additional influences were considered. Transmission pathways are not limited to life-course adversity. Rather, constructive parenting is maintained, in part, by engendering positive adjustment in offspring.

Keywords: antisocial behavior, parenting, temperament, positive adjustment, three generations

There is now converging evidence from well-designed prospective, intergenerational studies to support what many scientists, practitioners, and the lay public have suspected: The patterns of parenting and discipline that parents use with their children can be at least partially predicted from those their own parents used (e.g., Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005; Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scaramella, 2003). These assumptions have been based on the belief that children learn parenting practices from their parents (e.g., Patterson, 1998; Simons, Beaman, Conger, & Chao, 1992). What has been a surprise, however, has been the relatively modest strength of intergenerational associations (e.g., Capaldi, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2008; Capaldi, Pears, Patterson, & Owen, 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004). Therefore, additional approaches are being used to further understand the etiology of parenting practices, how they are transmitted from the first to the second generation (G1 and G2), and the effects on children in the second and third generations (G2 and G3).

The current study capitalizes on over two decades of fully prospective data and extends prior work on the intergenerational transmission of parenting and risk behaviors in two key respects. First, unique to this investigation, is the test of whether transmission of constructive parenting practices occurs via a positive adjustment pathway (through G2 adjustment in adolescence); this mechanism is contrasted against the well-supported antisocial behavior pathway (via G2 antisocial behavior in adolescence) by which negative parenting is transmitted. Second, we questioned whether G2 men’s parenting remains open to past and future influences across two developmental periods in G3 childhood. Specifically, we considered whether G1 parenting influences G2 parenting in both early and middle childhood for G3, as well as whether G3 temperament influences G2 constructive parenting over and above intergenerational pathways.

Constructive Parenting

As conceptualized in the current study, constructive parenting includes multiple aspects of parenting that contribute to positive child and adolescent adjustment. First, age-appropriate and consistent discipline buffers children and adolescents against the effects of a variety of stressful and negative events (Marshal & Chassin, 2000; Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein, & Sandler, 2000). Second, parental warmth and involvement may protect children from the development of externalizing behaviors by supporting the early development of self-regulation (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). Parental warmth also may limit growth in externalizing and internalizing behaviors among adolescents experiencing psychosocial difficulties (Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999). Third, effective parental monitoring has been linked consistently to positive adolescent development (e.g., Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Meece, 1999). Likewise, poor monitoring is a powerful predictor of problem behavior outcomes, including antisocial behavior (e.g., Ary, Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1999; Metzler, Noell, Biglan, Ary, & Smolkowski, 1994).

These features of constructive parenting change in salience over the course of development but remain associated. For example, parental monitoring becomes increasingly important in middle and late childhood and is critical to adjustment in adolescence (Crouter & Head, 2002; Snyder & Patterson, 1987). Yet, effective monitoring has early antecedents, including tracking, supervision, and communication within the context of a warm relationship (e.g., Crouter & Head; Patrick, Snyder, Schrepferman, & Snyder, 2005), and continues to depend upon the parent-child relationship in adolescence (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Thus, it is appropriate to jointly consider these related features of constructive parenting beginning in childhood.

The current focus on constructive parenting contrasts with prior work based on this and other cross-generational samples that primarily have considered continuities in negative parenting behaviors (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2003; Caspi & Elder, 1988; Conger et al., 2003; Hops, Davis, Leve, & Sheeber, 2003; Whitbeck et al., 1992). The limited number of intergenerational studies that have considered positive and productive aspects of parenting finds that supportive, consistent parenting in one generation is associated with the use of effective discipline practices in the next (Belsky et al., 2005; Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998; Chen & Kaplan, 2001; Simons et al., 1992; Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, Lizotte, Krohn, & Smith, 2003). The current study builds upon this evidence by examining a multiagent, multimethod measure of constructive parenting that is conceptually similar across generations and taps different informants at G1 and G2.

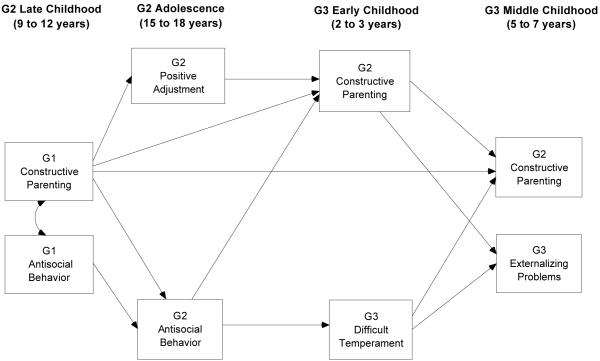

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical model guiding the current study. This model is based upon the dynamic developmental systems (DDS) approach (Capaldi, Kim, & Owen, 2008; Capaldi, Kim, & Pears, 2009; Capaldi, Shortt, & Kim, 2005), which emphasizes the interplay among biologic systems (e.g., genetic influences), individual characteristics (e.g., temperament), contextual factors (e.g., neighborhood and family resources), socialization experiences (e.g., coercive family processes), and social influence from both peers and romantic partners in explaining risk behaviors. The model for the current study highlights the connection between socialization in the family of origin and an individual’s own parenting practices. This is seen in the path from G1 constructive parenting practices in G2 boys’ late childhood to G2 fathers’ constructive practices of G3 children during middle childhood. This path follows from multiple studies of intergenerational continuity in harsh, hostile, inconsistent, and physical discipline (e.g., Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008; Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Scaramella & Conger, 2003); parental rejection (Whitbeck et al., 1992); poor supervision (Smith & Farrington, 2004); and, to a more limited extent, in positive aspects of parenting (e.g., Belsky et al., 2005; Chassin et al., 1998; Chen & Kaplan, 2001; Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting.

Mechanisms of Intergenerational Transmission: The Antisocial Behavior Pathway

The hypothesized indirect effects of G1 constructive parenting on G2 constructive parenting through G2 negative adjustment in adolescence are depicted in the lower third of Figure 1. This path is consistent with the emphasis of the DDS model on interplay between dyadic processes (e.g., parenting) and individuals’ cumulative developmental risks (e.g., G2 fathers’ adolescent delinquency). These indirect effects have been supported in multiple (though not all; see Conger et al., 2003) intergenerational studies of negative parenting (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003) and one of positive parenting (Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al., 2003). This antisocial behavior pathway suggests that intergenerational linkages in parenting are partially explained by the transmission of maladaptive behaviors and relational styles that generalize to parenting, rather than of parenting per se. Competing explanations for this pathway also must be noted. The heritability of factors relating to risk for difficult temperament and delinquency (Simonoff, 2001) also may underlie poor parenting behaviors, and difficult child temperament and problem behavior may elicit poor parenting behaviors (Ge et al., 1996). Therefore, manifestations of problem behaviors in all three generations are considered as potential influences on study outcomes.

Mechanisms of Intergenerational Transmission: Is There a Positive Adjustment Pathway?

To date, the DDS framework has been applied to explain the roles of problem behavior and negative personality characteristics in the intergenerational transmission of detrimental parenting practices (Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008). The current study advances this theory by evaluating youth positive adjustment (academic skills, positive peer relations, and self-esteem) as a mechanism through which constructive parenting is perpetuated across generations. Belsky (1984) and Heinicke (2002) highlight the importance of parents’ prebirth psychological resources, maturity, and capacity for sustained relationships, given that effective parenting demands impulse control, strong perspective taking, and feelings of security. In addition, positive adjustment among disadvantaged adolescents may hold promise for increasing economic and educational opportunities. With such opportunities, young parents might be exposed to additional sources of parenting support and information and might be less encumbered by contextual stressors (e.g., poverty) that negatively impact parenting (Hill, Stein, Keenan, & Wakschlag, 2006; Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al., 2003). Thus, in parallel to the indirect path via G2 antisocial behavior, a G2 positive adjustment pathway is depicted in the upper one third of Figure 1. This pathway represents cumulative developmental assets that may partially account for the intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting. It is important to note that we simultaneously model antisocial behavior and positive adjustment pathways. This approach stringently tests whether the latter offers a meaningful explanatory mechanism of parenting transmission or is simply an artifact of powerful continuities in problem behaviors and negative parenting across generations.

Constructive Parenting Across Childhood

An important advance represented in Figure 1 is that parenting constructs are examined within more comparable developmental periods relative to prior studies; that is, parenting of G2 is measured in late childhood and parenting of G3 in middle childhood. It has been repeatedly argued that intergenerational studies of parenting and antisocial behavior must strive for assessment of similar behaviors at similar developmental stages (Rutter, 1998; Thornberry, Hops, Conger, & Capaldi, 2003). Our prior work has yet to reach this ideal, because of the ages of the G3 children, although we have shown that intergenerational continuities in parenting are relatively robust to differences in the developmental stages at which they occur (Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008). Still, the current study builds upon this work by examining intergenerational features of parenting that are more comparable across generations in terms of measurement and developmental timing. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1, the current model clarifies whether transmission of parenting is completed in the earliest years of G2 fatherhood or whether G1 parenting impacts the unfolding of G2 parenting at multiple developmental stages in G3 children’s lives. Because the rewards, challenges, and demands of parenting may change considerably from early to middle childhood (see review by Demick, 2002), we hypothesize that G2 fathers’ parenting will remain open to influences, both current and past. Specifically, G1 parenting will predict G2 parenting in early childhood for G3 and relative change in G2 parenting from early to middle childhood.

Intergenerational Continuities in Problem Behavior

Intergenerational continuities in problem behaviors are depicted by the series of arrows across the bottom of Figure 1. Reviews of past literature (Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986), as well as multiple prospective intergenerational studies, consistently support these associations. Parents’ antisocial traits and criminal behaviors predict the problem behaviors of their offspring in different manifestations across multiple developmental periods, including difficult temperament and externalizing behavior problems in early childhood, conduct problems in middle to late childhood, and delinquency across early to late adolescence (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2003; Jaffee, Belsky, Harrington, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2006; Smith & Farrington, 2004). Direct effects of problem behaviors from G1 to G2 and from G2 to G3 may represent social modeling, inherited vulnerabilities, and continuities in detrimental environments that are unmediated by predictors examined in the current study.

Child Effects on Constructive Parenting

G3 child temperament represents a final hypothesized influence on G2 constructive parenting that is examined in the current study. Prior intergenerational studies have considered children’s difficult behavior as a control variable (e.g., Belsky et al., 2005; Capaldi et al., 2003) or as a moderator of intergenerational transmission (Scaramella & Conger, 2003), but not as a predictor of parenting. Theory and research support that coercive transactions between parents and children can begin in early childhood and exacerbate both child problem behavior and poor parenting (Scaramella & Leve, 2004) and that children’s behavior can influence the use of physical, harsh, and inconsistent discipline. Parents of young children with less challenging temperaments also are expected to have ongoing pleasurable and efficacious experiences with their children that, in turn, set the stage for less child oppositionality and aggression in middle childhood.

The current study offers a powerful test of child behavior effects on constructive parenting by considering G2 parent and G3 child behaviors across two developmental periods,. This perspective contrasts with a unidirectional conceptualization of parenting influences on child behavior. Embedding this transactional model within the broader model also strengthens conclusions that can be drawn about intergenerational influences on parenting, given that apparent associations between G1 and G2 parenting could be explained by early characteristics of G3 children. Thus, examining child effects on parenting within a prospective, intergenerational model is a critical next step in this field. Furthermore, although the current study focuses on the transmission of parenting, the model is equally positioned to test G2 fathers’ early parenting influences on G3 outcomes in middle childhood. Doing so within a rich intergenerational design is a significant contribution in its own right. Indeed, few studies that have focused on such questions control for potent familial vulnerabilities that could drive poor parenting and problem behavior across generations.

Hypotheses

On the basis of the model presented in Figure 1, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1

G1 constructive parenting of G2 boys in late childhood will be positively associated with G2 fathers’ constructive parenting of G3 children in early and middle childhood.

Hypothesis 2

Intergenerational continuity in constructive parenting is mediated by both G2 positive adjustment and antisocial behavior in adolescence.

Hypothesis 3

G2 constructive parenting and G3 behaviors show stability from early to middle childhood but show reciprocal influences. Specifically, G2 constructive parenting during G3 early childhood is negatively associated with G3 externalizing problems in middle childhood, and G3 difficult temperament in early childhood is negatively related to G2 constructive parenting in middle childhood.

Method

Participants

Second generation (G2) boys and their parents (G1) were originally recruited to the Oregon Youth Study (OYS), a study of individual, family, and community risk factors for delinquency. G2 boys were recruited in entire fourth-grade classrooms from six schools located in areas with higher-than-average delinquency rates. Schools were located in a medium-sized metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest. Seventy-four percent of invited G2 boys and their families were recruited (n = 206). Families were representative of the geographic area; 90% of boys were White, and most families were lower class (Hollingshead, 1975). At the first assessment (Wave 1 [W1] of OYS; G2 age 9-10 years), G1 mothers were a mean age of 33 years (SD = 4; range = 24 to 50) and fathers, 37 years (SD = 7; range = 27 to 57). Further details of recruitment and sample characteristics are reported in Capaldi and Patterson (1989). G2 boys were followed annually from ages 9 through 33 years, with annual participation rates of 94% or higher.

Offspring (G3) of G2 men, as well as mothers of G3, were recruited to the Three Generational Study (3GS). All children and cohabitating stepchildren of G2 men were originally eligible to participate in the 3GS. However, because of budgetary constraints, participation was later limited to the first 2 children born to the G2 men per biological mother. Assessments of G3 occur at age 21 months (Time 1 of 3GS [T1]), and ages 3 (Time 2 [T2]), 5 (Time 3 [T3]), and 7 (Time 4 [T4]) years. Because G3 children continue to be recruited to the 3GS as they are born, G3 sample sizes differ by assessment year. Thus, only G2 fathers with constructive parenting estimated at T3 or T4 were included in the current models, along with their G3 children who had T3 or T4 outcome data. As of November 2007, 181 G3 children (85 boys) of 102 G2 fathers met these criteria; 158 were biological offspring of G2 men, 21 were stepchildren, and 2 were adopted children. Fifty-one G2 males had a single participating child, 28 had 2 children, 18 had 3, and 5 had 4. At Time 1 (T1) of 3GS, the average age of G2 fathers was 25.1 years (SD = 2.5, range 20.0 to 29.8).

Procedures

G1 and G2 samples

G1 parents and G2 boys were assessed annually; methods included structured parent and child interviews, standardized and internally developed questionnaires, parent-child and peer interaction tasks, phone interviews with parents and boys, and home observations. Interviewers, observers, and coders of interaction tasks completed ratings of participants’ behaviors. School adjustment and achievement was assessed using teacher questionnaires and official records.

G3 sample

3GS assessments included mother and father interviews, standardized and internally developed questionnaires, and ratings of structured mother-child and father-child interaction tasks. G2 mothers reported on G2 fathers’ constructive parenting. Notably, the final assessment year used to calculate G2 antisocial behavior and positive adjustment in adolescence (Wave 9 [W9] of OYS) preceded the first assessment year used to assess fathers’ constructive parenting (T1 of 3GS).

Measures

Because of space limitations and the number of measures forming the observed constructs, information on general content, sample items, and scale statistics are summarized in Appendix A and B. Further details are available from the authors upon request. Unpublished instruments developed at Oregon Social Learning Center (OSLC, 1982-2007); complete referencing details can be found at http://www.oslc.org/unpublished_oslc_instruments.pdf. Prior work with this sample has supported the validity of the constructs considered here (Capaldi et al., 2003; Capaldi & Patterson, 1989; Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008), and the construct development process itself systematically establishes the convergent validity of component scales. Thus, the psychometric properties of each construct indicator are not discussed further.

Construct development

Data from multiple measures and agents across multiple assessment years were used to first create specific constructs of interest (e.g., monitoring) and then global constructs used in modeling (e.g., constructive parenting). Items and scales were considered for inclusion in constructs on the basis of precedence in the literature, face validity, and comparability across ages and generations. Two criteria specified by Patterson and Bank (1986) guided construct development: First, items included in a scale had to show acceptable internal consistency (i.e., an alpha of .60 or higher and an item-total correlation of .20); second, scales had to converge with other indicators designed to assess the same construct (i.e., the factor loading for a one-factor solution had to be .30 or higher). Occasions are specified when scales were created from face-valid indicators, despite failure to reach these statistical criteria. Scales were formed for each instrument with relevant items. Constructs were based on the mean of standardized component scales. Global constructs used in modeling were based on the mean of standardized constructs.

Appendix A describes G1 parenting and G2 adolescent behavior constructs; Appendix B summarizes G2 parenting and G3 characteristics. These tables are organized on the basis of how items, scales, and constructs were combined. An extended example is illustrative (see Appendix B): G2 positive adjustment was calculated as the mean of the three standardized positive adjustment constructs developed at Wave 5 (W5), Wave 7 (W7), and W9 (ages 14, 16, and 18 years, respectively). W5 positive adjustment was the mean of the three standardized constructs: academic skills, peer relations, and self-esteem. The W5 academic skills construct was the mean of three standardized component scales: parent-reported academic skill (the mean of standardized mother- and father-report scales), teacher-reported academic skill, and official school-testing records.

G1 constructive parenting of G2 boys in late childhood

G1 constructive parenting was assessed at W1 (ages 9-10 years), Wave 2 (W2; ages 10-11 years), and Wave 3 (W3; ages 11-12 years) of OYS. The final construct consisted of four component constructs, variations of which have been described in Capaldi and Patterson (1989) and used in prior OYS publications (e.g. Kim, Capaldi, & Stoolmiller, 2003; Wiesner & Capaldi, 2003): monitoring, parent involvement, positive parent-child relationship, and confident/efficacious discipline (see Appendix A). Each was measured by computing the mean of standardized constructs formed within assessment waves.

G1 monitoring was based on parent and child in-person and telephone interviews and ratings completed by interviewers (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G1 parent involvement was comprised of child and parent in-person and telephone interviews, interviewer rating, child and parent questionnaire reports on the Family Activities Checklist regarding activities with the child in the past week, and staff ratings following home observation (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G1 positive parent-child relationship was based on child and parent interview scales, home observer ratings, and parent interviewer ratings, child reports on the Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), and Social Control Questionnaires (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G1 confident/efficacious discipline constructs were formed from the Poor Implementation (measuring calmness, consistency, and follow through) and Low Confidence (measuring perceived effectiveness of disciplinary efforts) subscales derived from mother and father interviews (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G1 antisocial behavior during G2 boys’ late childhood

The G1 antisocial behavior construct has been described elsewhere (e.g., Capaldi & Patterson, 1989; Kim et al., 2003); it was based on assessments completed at OYS inW1 (G2 ages 9-10 years), W2 (ages 10-11 years), and W3 (ages 11-12 years) and was computed as the mean of standardized mother and father constructs. These, in turn, were based on the mean of the following three parent-specific indicators; the mean of self-report Hypomania/Psychopathic Deviate subscales from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, 1951) and Life Events Survey (Holmes & Rahe, 1967), the mean of total official arrests and motor vehicle license suspensions through W1, and (despite low internal consistency) the mean of face-valid ratings by assessment staff (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G2 positive adjustment in adolescence

Positive adjustment for G2 during adolescence was formed as the mean of constructs from OYS in W5 (ages 13-14 years), W7 (ages 15-16 years), and W9 (ages 17-18 years), each of which was formed as the mean of academic skills, peer relations, and self-esteem (W5 and W7 only) constructs at each assessment year.

G2 academic skills were measured at W5, W7, and W9 as the means of relevant scales on the parent Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991b) and official school records (standardized test percentiles and grade point average), an approach used in other OYS publications (e.g., Stoolmiller, Kim, & Capaldi, 2005; Wiesner & Capaldi, 2003).

G2 positive peer relations were measured at OYS W5, W7, and W9; indicators were parent reports on the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983), Peers Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007), and Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007, adapted from Walker & McConnell, 1988); teacher reports on the Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991b) and Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire; coder ratings on a laboratory interaction tasks with a peer (OSLC, 1982-2007); and child report on the Peer Attachment Questionnaire (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), Social Control Questionnaire, Describing Friends (OSLC, 1982-2007), Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007), and Inventory of Peer Activities (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G2 self-esteem was computed as the mean of W5 and W7 scales. At W5, the mean of three standardized subscales of the self-report Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter, 1982) was computed: Global Self-Worth, Scholastic Competence and Social Acceptance Scales. At W7, the mean of six standardized subscales of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988) was used: Global Self-Worth, Scholastic Competency, Social Acceptance, Job Competence, Romantic Appeal, and Close Friendship Scales.

G2 antisocial behavior in adolescence

The antisocial behavior construct has been described in numerous OYS publications (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2003; Capaldi & Patterson, 1989); it was based on the mean of antisocial and delinquency constructs created at OYS in W5 (ages 13-14 years), W7 (ages 15-16 years), and W9 (ages 17-18 years). These constructs, in turn, were based on parent interviews (OSLC, 1982-2007) and reports on the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and Peer Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007); teacher reports on the Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991b) and Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007); child self-report on the Elliott Delinquency Scale (Elliott, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, & Canter, 1983), child interview, and Activity Preferences Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007); interviewer ratings (OSLC, 1982-2007); and official arrest records.

G2 constructive parenting of G3 in early childhood

As summarized in Appendix B, G2 fathers’ early constructive parenting of G3 children was calculated as the mean of parenting constructs computed at T1 (age 21 months) and T2 (age 3 years) of 3GS. These constructs were first formed separately on the basis of both parents’ reports of fathers’ confident and efficacious discipline and father-reported warmth and pleasure in parenting, which were significantly associated within assessment year. Measures of fathers’ parenting included the same confident and efficacious discipline items completed by G1 parents but were supplemented by mothers’ reports of fathers’ behaviors to create a multiagent measure. Monitoring items were developmentally inappropriate and thus were not administered. Pleasure and participation in developmentally specific activities (e.g., bathing and feeding), as well as positive verbal and physical responses to child behaviors, were used in place of the involvement and relationship scales administered to G1.

G2 confident/efficacious discipline has been described previously (e.g., Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008) and was based on G2 fathers’ and mothers’ reports of G2 fathers’ constructive parenting. These indicators were based on two Parenting Questionnaire subscales (OSLC, 1982-2007): Poor Implementation and Low Confidence. Fathers’ self-reported constructive parenting was formed as the mean of three indicators. The first was self-reported efficacious discipline (identical to the mother-report subscale).

G2 warmth and pleasure in parenting constructs formed the second and third self-report indicators of fathers’ constructive parenting; specifically, the Pleasure in Parenting Scale (Fagot, 1995) and the Parent Daily Report (Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) of physically or verbally positive responses to child behaviors that occurred in the previous 24 hr.

G3 difficult temperament in early childhood

Difficult G3 child temperament was formed as the mean of parent reports at 3GS T1 (age 21 months) and T2 (age 3 years). At T1, the Anger and Activity Level subscales of the parent-reported Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (Goldsmith, 1996) were used. At T2, the Activity Level, Anger, Impulsivity, Low Inhibitory Control, and Discomfort subscales from the more developmentally appropriate Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001) were used.

G2 constructive parenting of G3 in middle childhood

G2 constructive parenting in middle childhood was formed as the mean of 3GS T3 (age 5 years) and T4 (age 7 years) indicators. The T3 indicators were positive father-child relationship and confident and efficacious discipline. The T4 construct was based on efficacious discipline, monitoring, involvement with child, and positive father-child relationship indicators.

Confident and efficacious discipline items were identical to those used to assessed G2 parenting in early childhood and included all those used to assess G1 parenting in late childhood. Monitoring items were included at T4 as this domain of parenting became more developmentally salient. Parent involvement and relationship questions differed from those used in early childhood, according to developmental changes in caregiving and shared activity. Although similar aspects of parent involvement and parent-child relationship were assessed for G2 fathers during G3 middle childhood and G1 parents in G2 late childhood, the latter assessments included more child and staff reports because of study design, convergence of candidate items, and older children’s capacities to participate in measurement.

G2 confident and efficacious discipline was based on fathers’ and mothers’ reports of fathers’ Poor Discipline Implementation and Low Confidence in Discipline subscales of the Parenting Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007) that was described above.

G2 monitoring was measured at T4 only and was the mean of a 4-item scale from the parent interview (OSLC, 1982-2007) and a staff rating following the parent interview (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G2 paternal involvement was formed at T4 only and was the mean of a parent interviewer rating (OSLC, 1982-2007) and a self-report indicator consisting of three subscales: a count of shared activities from the Family Activities Checklist (OSLC, 1982-2007); parent interview items; and an indicator based on items from the Monitor and Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007) that tapped custody arrangements, time spent in discussions with child, and time spent with child.

G2 positive father-child relationship was based on items and scales from the Monitor and Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007), the Child Rearing Practices Report (Block, 1965), and the Child Relationship with Parents Questionnaire (OSLC, 1982-2007).

G3 externalizing behavior problems in middle childhood

Parents rated G3 children’s externalizing behavior problems using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991a). Means of standardized scores at 3GS T3 (age 5 years) and T4 (age 7 years) were computed separately for mothers and fathers; mean parent reports were used for the final construct.

Data Analyses

Observed variable path analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2007). The complex sample analysis option -- which assumes independence only among cluster units, not individual cases -- was used to adjust standard errors for nonindependence of (in many cases) multiple G3 children per G2 father (Williams, 2000). G1 and G2 antisocial behavior, G2 adjustment, G2 constructive parenting of G3 in early childhood, and G3 externalizing behavior variables were transformed in order to more closely approximate a normal distribution. All constructs were standardized (thus, all Ms = 0, SD = 1).

Missing Data

Complete data on all eight constructs were available for 85% of cases; 5% were missing data on one variable, 9% on two variables, and 1% on three variables. All cases had data for G1 constructs and G2 adjustment, and only four cases were missing G2 antisocial behavior. The lowest covariance coverage (85%) was between G2 antisocial in adolescence and G2 parenting of G3 in early childhood. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used, as it has been shown to provide unbiased estimates when data are missing at random (Arbuckle, 1996).

Results

Correlations among the eight study variables are presented in Table 1. Significant intergenerational continuities were evident in the associations G1 constructive parenting of G2 during late childhood had with G2 parenting of G3 both in early and middle childhood. Other key associations are identified in the context of the path model depicted in Figure 1 that was used to test study hypotheses; specifically, we predicted that the constructive parenting G2 fathers experienced during late childhood would predict their own constructive parenting of G3 during early childhood and in middle childhood, beyond continuity in parenting practices from early childhood. We further hypothesized that G2 positive adjustment and antisocial behavior during adolescence would partially mediate intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting from G1 to G2 in G3 children’s early childhood, and that G3 difficult temperament during early childhood would negatively and uniquely impact G2 constructive parenting of G3 during middle childhood. Covariances between variables measured concurrently (e.g., G2 constructive parenting and G3 difficult parenting) also were allowed.

Table 1. Correlations among Model Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 Late Childhood | 1. G1 constructive parenting | -- | |||||||

| 2. G1 antisocial | -.15* | -- | |||||||

| G2 Adolescence | 3. G2 positive adjustment | .51*** | -.14 | -- | |||||

| 4. G2 antisocial | -.33*** | .47*** | -.44*** | -- | |||||

| G3 Early Childhood | 5. G2 constructive parenting | .33*** | -.11 | .36*** | -.20* | -- | |||

| 6. G3 difficult temperament | -.26** | .10 | -.24** | .23** | -.57*** | -- | |||

| G3 Middle Childhood | 7. G2 constructive parenting | .35*** | -.08 | .30*** | -.10 | .48*** | -.31*** | -- | |

| 8. G3 externalizing | -.16* | .17* | -.22** | .15 | -.36*** | .41*** | -.42*** | -- | |

| N | 181 | 181 | 181 | 177 | 157 | 163 | 181 | 181 | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

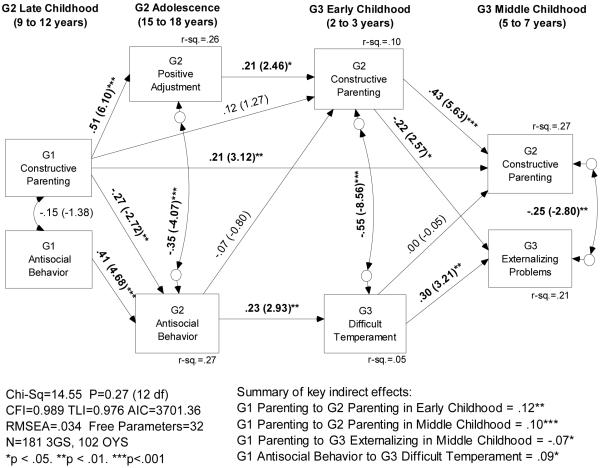

Model fit statistics and coefficients for direct, indirect, and covariance paths are summarized in Figure 2. As suggested by the correlation in Table 1, G1 constructive parenting of G2 during late childhood was associated with G2 constructive parenting of G3 in early childhood (total effects β = .24, p < .01); of note, however, was that the association was largely indirect. The only specific path that was significant was indirect through G2 positive adolescent adjustment (indirect β = .10, p < .05). G1 constructive parenting also predicted G2 constructive parenting of G3 during middle childhood (total β = .31, p < .001); effects were via a direct path (β = .21, p < .01) and individually nonsignificant indirect paths (total indirect β = .10, p < .01). There was no evidence that G2 antisocial behavior in adolescence mediated the intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting measured in G3 early or middle childhood (indirect β = .02 and .01, respectively, p = ns).

Figure 2.

Final path model of intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting.

X2 (12, N = 181) = 14.55, p = .27: CFI = .989, TLI = .976: Akaike information criterion = 3,701.36: root-mean-square error of approximation = .034: free parameters = 32. N = 181 children of 102 fathers. Summary of key indirect effects: G1 Parenting to G2 Parenting in Early Childhood = .12**; G1 Parenting to G2 Parenting in Middle Childhood = .10**; G1 Parenting to G3 Externalizing in Middle Childhood = -.07*; G1 Antisocial Behavior to G3 Difficult Temperament = .09*. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Not surprisingly, G2 constructive parenting and G3 problem behavior (difficult temperament and externalizing problems) each showed significant stability from early to middle childhood. G2 constructive parenting and G3 problem behaviors also were negatively associated within developmental period. As hypothesized, G2 constructive parenting of G3 in early childhood predicted fewer externalizing behavior problems in middle childhood. There was no evidence, however, that G3 difficult temperament in early childhood influenced G2 constructive parenting in middle childhood.

Problem behavior showed intergenerational continuity from G1 to G2 and from G2 to G3. Furthermore, G1 antisocial behavior was associated with G3 difficult temperament in early childhood via G2 boys’ antisocial behavior in adolescence (indirect β = .09, p < .05). Although modest, G1 constructive parenting also had detectable indirect effects on G3 behavior outcomes. Specifically, G1 constructive parenting was associated with G3 externalizing problems (total indirect β = -.07, p < .05). In all, predictors explained 27% of the variance in G2 constructive parenting in middle childhood and 21% in G3 externalizing behavior problems.1

Discussion

Multiple influences on fathers’ constructive parenting practices were considered on the basis of the DDS model (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2005). As such, significant influences were hypothesized from men’s (a) childhood experiences within the parent-child system of their families of origin; (b) adolescent antisocial behavior and positive adjustment, reflecting the cumulative developmental risks and assets they would bring to the task of parenting, as well as heritable behavioral traits; and (c) parenting experiences within the parent-child system of their families of procreation.

Evidence for Intergenerational Continuity in Constructive Parenting

Unique to the current study were hypotheses regarding the intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting, a robust composite of parenting behaviors that each has been linked to healthy child development and fewer problem behavior outcomes; namely, parental monitoring, involvement, effective discipline, and relational warmth (e.g., Ary et al., 1999; Pettit et al., 1999). As hypothesized, G1 parents’ constructive parenting of G2 boys in late childhood predicted G2 fathers’ constructive parenting of G3 children in early and middle childhood. In this respect, findings were consistent with those based on this and other samples regarding intergenerational continuities in detrimental (e.g., Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008; Conger et al., 2003) and productive (e.g., Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al., 2003) parenting practices.

Also consistent with the study hypotheses was the finding that G1 parenting predicted relative changes in G2 constructive parenting from early to middle childhood for G3. This result may suggest that childrearing experiences in the family of origin exert new effects on parenting as children enter later developmental periods. That is, as the developmental tasks of G3 require additional parenting skills and relational capacities, G2 fathers may draw anew upon learning that occurred in childhood. Such an interpretation is consistent with parental stage theories (see Demick, 2002), which posit that adults develop in the parental role in parallel with their children’s development. Direct intergenerational effects of constructive parenting could also reflect instrumental (e.g., help with childcare and finances) and emotional support and advice that G1 parents provide G2 men and their partners during early parenting years (see Zarit & Eggebeen, 2002).

Intergenerational Continuity in Parenting: Positive Adolescent Adjustment Pathway

As hypothesized, G1 constructive parenting predicted G2 fathers’ constructive parenting, in part, through associations with G2 boys’ positive adjustment in adolescence. These mediational findings are based on the most rigorous test of this hypothesis to date and represent a unique contribution of the current study. One other study by Chen and Kaplan (2001) reported that the transmission of constructive parenting from G1 to G2 was partially explained by intervening G2 adult social participation and interpersonal relations constructs (i.e., educational attainment, organizational participation, and feelings about family and peer relationships). Although theoretically important, the Chen and Kaplan study relied on a single informant to rate independent, dependent, and intervening variables and examined different parenting constructs across generations. The current findings suggest that, indeed, productive aspects of parenting, such as parental monitoring, involvement, consistent discipline, and warm parent-child relations, impact similar constructive parenting behaviors in the subsequent generation by supporting youth achievement, self-esteem, and positive peer relations. Thus, the current study replicates Chen and Kaplan’s model by examining dimensions of positive adjustment in adolescence that may initiate the mediating process these authors observed in adulthood. Findings suggest a conclusion that mirrors the life-course adversity perspective regarding the way intergenerational linkages in poor parenting are explained by problem behaviors and contexts. That is, an important part of what is transmitted to children through supportive and consistent environments may not be parenting behaviors per se, but a host of cognitive and interpersonal assets that are applied to functioning in diverse adult roles, including parenthood. That these effects were independent of the antisocial behavior pathway was especially impressive and theoretically meaningful.

Intergenerational Continuity in Parenting: Adolescent Antisocial Behavior Pathway

Contrary to expectation, G2 antisocial behavior in adolescence was not independently associated with constructive parenting and thus did not mediate the transmission of constructive parenting across generations. This pattern of findings contrasts with those from a prior study based on the current sample (Capaldi et al., 2003), indicating that harsh parenting shows intergenerational continuity, due in part to the transmission of problem behavior. Because of the relatively modest sample size, we can not rule out low statistical power as an explanation for this difference, given the complexity of model examined. In addition, differences in the parenting constructs examined in the current study may account for the contrasting pattern of findings.

Consistent with the study hypotheses, G1 constructive parenting practices were associated both with higher levels of positive adjustment and lower levels of antisocial behavior in G2 adolescents. Each effect has been supported in prior studies, but few have considered these youth outcomes simultaneously. Positive adjustment and antisocial behavior were related but were nonoverlapping constructs in adolescence. Findings that parenting efforts in late childhood influence positive developmental outcomes, and not just the absence of deviant outcomes, offer powerful support for the potential value of prevention efforts. Furthermore, although modest, there was evidence that G1 constructive parenting practices contributed indirectly to fewer externalizing behavior problems among G3 children. This result hints at the possibility that changing parenting practices in one generation can have a cascade of positive effects across subsequent generations.

Intergenerational Continuities, But No Support for Child Effects on Parenting

As in prior studies (e.g., Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986), there was support for modest intergenerational continuities in problem behaviors. Specifically, G1 antisocial behavior was positively related to G2 antisocial behavior in adolescence, which predicted difficult temperament characteristics in G3 children; furthermore, there was a significant indirect path from the G1 problem behavior to G3 temperament.

The inclusion of G3 behavior patterns in the study model strengthens general conclusions that can be drawn regarding intergenerational processes. Namely, G2 parenting behaviors and G3 difficult temperament were moderately associated in early childhood. Therefore, it would have been reasonable to question whether associations between G1 parenting and G2 parenting in middle childhood might reflect familial vulnerabilities manifest in G3 temperament that, in turn, negatively impacted G2 fathers’ subsequent constructive parenting. However, inclusion of G3 temperament in the path model did not weaken evidence of intergenerational transmission of parenting. Surprisingly, although G2 parenting and G3 difficult behaviors were negatively associated in early and middle childhood, there was no support for effects of early G3 child behavior on relative changes in G2 parenting.

In contrast, G2 constructive parenting in early childhood was associated with fewer externalizing behavior problems in middle childhood of G3, even after accounting for developmental continuity from G3 difficult temperament. Familial background variables (e.g., G1 and G2 problem behavior) were comprehensively measured and temporally distinct from the portion of the model testing parent-child reciprocal effects. Therefore, these findings represent an advance over typical prospective studies of social and developmental risk in childhood. We suspect that parent-child coercive processes do occur (e.g., Scaramella & Leve, 2004) but that other designs (e.g., multiple assessments within early childhood) may be better able to detect them.

Estimates of Intergenerational Continuities Remain Modest

Consistent with previous studies, G1 parenting explained a relatively limited amount of variance in G2 parenting (10% - 12%). This leads to consideration of what other factors influence young fathers’ parenting practices. We have hypothesized that mothers of G3 children are a key source of such influence, and therefore they partially explain intergenerational discontinuity in fathers’ parenting practices (Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008). This hypothesis is generated by the emphasis of the DDS model on social influence within key dyads and on specific influences (e.g., parenting to parenting). A test of this hypothesis regarding influences on the OYS men’s poor and harsh discipline practices indicated that mother’s problem behavior (substance use and antisocial behavior) and negative discipline practices accounted for additional variance--controlling for poor discipline experienced in the men’s family of origin, as well as for the men’s own problem behavior, ages at which they became fathers, and family socioeconomic status (SES). Thus, romantic partners appear to be key sources of influence on men’s parenting that should be considered in future investigations.

A Focus on Fathers

A strength of the current study was the focus on parenting practices of fathers, who are often neglected in developmental research (Phares, Fields, Kamboukos, & Lopez, 2005). Intergenerational associations have been reported for fathers in this and another sample (Capaldi et al., 2003; Capaldi, Pears, et al. 2008; Chen & Kaplan, 2001). However, at least two other intergenerational studies have found significant direct effects only on G2 mothers’ parenting (Belsky et al., 2005; Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al., 2003). Both studies relied heavily or exclusively on maternal reports at G1 and focused on warm and positive aspects of parenting, as opposed to the poor and harsh parenting that has been modeled with the OYS sample. In addition, Belsky and colleagues considered a New Zealand birth cohort sample. Thus, it was important to test whether discrepant study findings were because of differences in sample risk characteristics, G1 informant, and focus on positive versus negative parenting behaviors. Indeed, we found support for the transmission of constructive parenting practices from G1 mothers and fathers to at-risk G2 fathers. Furthermore, although Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, et al. (2003) proposed that intergenerational continuities in parenting occur directly for women but occur because of delinquency in men, our findings did not support this pattern for OYS fathers; rather, we found direct transmission of constructive parenting and no significant additive or mediating effect from adolescent antisocial behavior.

Limitations

There were some limitations to the current study. First, the sample size did not permit latent variable modeling; thus, path estimates, including the overall estimate of intergenerational continuity in parenting, may have been underestimated. Second, although multiple influences on fathers’ constructive parenting were considered, it remains possible that other factors could mediate remaining intergenerational associations that were interpreted here as direct effects. Of note, in a prior study, neither G2 mothers’ adult problem behavior, G2 mothers’ poor or harsh discipline, G2 family socioeconomic status, nor G2 fathers’ age at the birth of their first offspring mediated intergenerational effects (Capaldi, Pears, et al., 2008). Third, the developmental periods at which parenting of G2 and G3 participants was measured were more comparable than in prior studies based on this sample but were not identical. Fourth, because OYS men who became fathers early had higher levels of adolescent risk characteristics (Fagot, Pears, Capaldi, Crosby, & Leve, 1998; Pears, Pierce, Kim, Capaldi, & Owen, 2005), fathers of G3 children who were old enough to be eligible for participation in the current study were likely to show higher levels of risk than nonfathers and fathers who formed families more recently. Fifth, the study did not test the extent to which traits showing evidence of heritability (e.g., impulsivity, agreeableness; Kruesi et al., 1990) that are likely to influence all of the behaviors represented in the model contributed to apparent continuities.

General Conclusions

Findings from the current prospective, intergenerational study of fathers’ constructive parenting practices are consistent with a DDS model. In particular, inter- and intragenerational continuities in individual characteristics and socialization experiences are identifiable and reflect interactions within systems in the family of origin and the family of procreation. Of theoretical importance, the DDS model has thus far been applied only to the study risk processes. The current findings suggest the model may be used to understand constructive and protective interactions, intergenerational continuities in adaptive processes, and the cumulative developmental assets that individuals bring to the tasks of parenting and other adult roles. Findings have important implications for preventive interventions and suggest that targeting specific parenting behaviors may influence positive adolescent outcomes as well as decrease problem behavior. Furthermore, results provide evidence that the effects of prevention may be wider in scope than is typically imagined, because changes in parenting may lead to enhanced functioning in adult children and even grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by Grant DA 051485 from the Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS). Additional support was provided by Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), U.S. PHS and Grant HD 46364 from the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development Branch, NICHD and Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, NIDA, NIH, U.S. PHS.

The authors would like to thank Shivan Tucci, Lisa Bruckner, and Jane Wilson for project coordination; Sally Schwader for editorial assistance; and the children, parents, and teachers who volunteered to participate in this research study.

Appendix

Appendix A.

G1 Parenting and Behavior and G2 Adolescent Behavior Constructs and Measures Used in the Current Study

| Construct/Measure | Agent | Items | α / r | Sample Item |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Constructive Parenting in G2 Late Childhood | Multi | 4 | .78 | |

| G1 Monitoring | Multi | 2 | .57 | |

| G1 monitoring, W1 | Multi | 3 | .50 | |

| Monitoring, parent interview | I | 3 | .70 | How carefully does the mother monitor the child? |

| Monitoring, child interview | TC | 6 | .55 | How often do you check in after school? |

| Time spent with son, parent phone interview | P | 1 | -- | In the past 24 hours, how many hours did you spend with your son? |

| G1 Monitoring, W3 | Multi | 5 | .61 | |

| Monitoring, mother interview | M | 5 | .60 | How often do you discuss plans for the coming day with TC? |

| Monitoring, child Interview | TC | 5 | .64 | How often do you tell parents when you’ll be back? |

| Time Spent with Son, parent phone interview | P | 2 | .11a | How many hours did you spend with the child yesterday? |

| Time Spent with Son, child phone interview | TC | 2 | .58 | Did parents talk to you about plans for the day? |

| Monitoring, parent interview | I | 3 | .60 | Child seems well supervised by parents. |

| G1 Parent Involvement | Multi | 2 | .51 | |

| G1 Parent Involvement, W1 | Multi | 2 | .27 | |

| Parent Involvement, child self-report | TC | 2 | .43 | |

| Parent Involvement, child interview | TC | 2 | .31 | About how many hours a week do you spend with your mom doing something special that you enjoy? |

| Family Activities Checklist | TC | 2 | .80 | |

| Sum of Activities, with mother (father) | TC | 28 | .84 (.83) | Please circle whether or not you did the following activities in the past week: Give her/him a hug or kiss? |

| Parent involvement, parent reports | P | 4 | .58 | |

| Family Activities Checklist | P | 2 | .56 | |

| Sum of Activities, with TC | M (F) | 28 | .70 (.69) | Go for a walk together |

| Activities, parent phone interview | P | 1 | -- | Have you or your spouse taken your son to some activity in the past 3 days? |

| Activities, parent interview | P | 2 | .23 | How many days a week do you sit and talk with your son? |

| Parent Involvement, parent interview | I | 2 | .67 | Parent seemed to enjoy parenting. |

| G1 Parent Involvement, W3 | Multi | 6 | .64 | |

| Parent Involvement, parent interviews | P | 2 | .20 | |

| Mother (father) interview | M (F) | 4 | .61 (.64) | How much time weekly do you spend talking with TC? |

| Family Activities Checklist | P | 2 | .31 | |

| Sum of activities, with TC | M (F) | 28 | .72 (.76) | |

| Parent Involvement, home observation | O | 2 | .56 | Mom/Dad explained or discussed (with child) political, moral, religious, or philosophical issue or other global topic? |

| Parent Involvement, child interview | TC | 2 | .57 | |

| Mother (father) involvement | TC | 3 | .67 (.75) | In the last year, how often have you done activities such as sports, hobbies, or games with your mother? |

| Parent Involvement, child phone interview | TC | 1 | -- | In the last 24 hours, were there any activities that you and one of your parents did together? |

| Family Activities Checklist | TC | 2 | .73 | |

| Sum of Activities, with mother (father) | TC | 28 | .86 (.85) | |

| G1 Parent-Child relationship | Multi | 2 | .63 | |

| Parent Child Relationship, W1 | Multi | 4 | .51 | |

| Parent-Child Relationship, parent interviews | P | 2 | .53 | |

| Mother (father) interview | M (F) | 4 | .74 (.63) | Has son been pleasant to raise? |

| Parent-Child Closeness, home observation | O | 2 | .62 | |

| Mother (Father)-Child Closeness | O | 2 | .66 (.79) | Mother and child shared friendly relations. |

| Parent-Child Relationship, child interview | TC | 2 | .66 | How well do you get along with your mom? |

| Parent-Child Relationship, parent interview | I | 2 | .58 | (Mom) seemed generally accepting of son. |

| G1 Parent-Child Relationship, W3 | Multi | 3 | .72 | |

| Mother-Child Relationship | Multi | 3 | .71 | |

| Mother interview | M | 6 | .76 | Has son been pleasant to raise? |

| Home observation | O | 9 | .88 | Mom was physically affectionate with child. |

| Mother interview | I | 2 | .76 | Mom was generally accepting of child. |

| Father-Child Relationship | Multi | 3 | .71 | |

| Father interview | F | 6 | .76 | How well do you get along with your son? |

| Child interview | TC | 1 | -- | Generally speaking, how well do you get along with father? |

| Father interview | I | 2 | .65 | Dad seemed to enjoy parenting. |

| Parent-Child Relationship, child reports | TC | 2 | .54 | |

| Parent and Peer Attachment Questionnaire | TC | 12 | .78 | My parents respect my feelings. |

| Social Control Questionnaire | TC | 7 | .86 | How do you describe your parents (scale of fair to unfair)? |

| G1 Confident/Efficacious Discipline | P | 2 | .65 | |

| G1 Poor Discipline (R), W1 | P | 2 | .26 | |

| Poor Discipline, mother (father) interview | M (F) | 2 | .47 (.42) | |

| Poor Implementation | M (F) | 4 | .56 (.59) | How often do you follow through with threatened punishment? |

| Low Confidence | M (F) | 3 | .64 (.55) | Does your son get away with things? |

| G1 Poor Discipline (R), W2 | P | 2 | .48 | Do you generally have problems managing your son? |

| G1 Poor Discipline, mother (father) interview | M (F) | 2 | .44 (.47) | |

| Poor Implementation | M (F) | 6 | .71 (.70) | How often are you angry when you punish your son? |

| Low Confidence | M (F) | 3 | .78 (.67) | How satisfied are you with your son’s behavior? |

| G1 Antisocial Behavior in G2 Late Childhood | Multi | 2 | .56 | |

| G1 Mother (father) Antisocial Behavior | Multi | 3 | .55 (.57) | |

| Self-Report | M (F) | 2 | .16 (.14a) | |

| MMPI, items, W2 | M (F) | 15 | .62 (.69) | At times it has been impossible for me to keep from stealing or shoplifting. |

| Life Events Survey, W3 | M (F) | 3 | .87 (.94) | Number of times (you were) arrested in the last year. |

| Official Records, W1 | Records | 2 | .26 (.43) | |

| Total motor vehicle license suspensions to date | Records | * | -- | 0 to 3+ license suspensions |

| Total arrests to date | Records | * | -- | Total arrest count |

| Staff Ratings of Mother(Father) Behavior | Multi | 2 | .36 (.31) | |

| Ratings, W1 | Multi | 3 | .36 (.40) | |

| Family Interaction Task | C | 1 | -- | Mother encouraged antisocial behavior. |

| Home observation | O | 6 | .73 (.84) | Percent of time father spent misbehaving. |

| Parent interview | I | 1 | -- | Mother’s general social attitude. |

| Ratings, W3 | Multi | 3 | .22 (.26) | |

| Family Interaction Task | C | 1 | -- | Mother encouraged antisocial behavior. |

| Home observation | O | 4 | .74 (.71) | Father clearly indicated anger/irritability. |

| Parent interview | I | 1 | -- | Mother’s general social attitude |

| G2 Positive Adjustment in Adolescence | Multi | 3 | .84 | |

| G2 Positive Adjustment, W5 | Multi | 3 | .72 | |

| G2 Academic Skills | Multi | 3 | .86 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .65 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 4 | .85 (.87) | TC’s reading or English performance |

| Teacher Report Form | T | 4 | .94 | TC’s spelling performance |

| Standardized school testing | Records | 4 | .91 | Reading percentile |

| G2 Positive Peer Relations | Multi | 3 | .61 | |

| Parent report | P | 3 | .79 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | M, F | 6 | .79 | Number of times a week child does things with friends. |

| Peers Questionnaire | M, F | 4 | .78 | How many friends has your son made in the past year? |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | P | 2 | .56 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 6 | .86 (.86) | Other kids seek to involve your child in activities. |

| Peer Task | C | 1 | -- | TC relates well to other children. |

| Teacher report | T | 2 | .56 | |

| Teacher Report Form | T | 3 | .85 | TC doesn’t get along with other pupils. |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | T | 6 | .93 | TC plays, talks with peers for a long time. |

| G2 Self-esteem (Perceived Competence Scale) | TC | 3 | .67 | |

| Three subscales (e.g., Scholastic Competence) | TC | 6 | .77-.82 | Some kids often forget what they learn BUT other kids remember things easily. (TC answers either pole is “sort of” or “really true of me”) |

| G2 Positive Adjustment, W7 | Multi | 3 | .60 | |

| G2 Academic Skills | Multi | 4 | .84 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .74 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 4 | .85 (.92) | TC’s spelling performance |

| Teacher Report Form | T | 4 | .92 | TC’s language arts performance |

| Standardized school testing | Records | 4 | .94 | Language percentile |

| Grade-point average | Records | 1 | -- | Total year grade-point average |

| G2 Peer Relations | Multi | 4 | .59 | |

| Parent reports | P | 3 | .84 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | M | 4 | .64 | How many close friends does child have? |

| Peers Questionnaire | M | 4 | .63 | Son has best friend he sees often. |

| Peer Involvement and Social Skills Questionnaire | P | 2 | .38 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 6 | .89 (.88) | TC makes friends easily with other kids. |

| Peer Task | C | 1 | -- | TC relates well to other children. |

| Child reports | TC | 4 | .52 | |

| Peer Attachment Questionnaire | TC | 9 | .87 | My friends are good friends. |

| Social Control Questionnaire | TC | 2 | .34 | |

| School and Neighborhood Peers Subscales | TC | 7 | .91-.93 | School peers are friendly. |

| Inventory of Peer Activities | TC | 24 | .87 | With friends in general, how often go to the movies? |

| Describing Friends Questionnaire | TC | 1 | -- | How many very good friends do you have? |

| Teacher Report Form | T | 3 | .87 | Child doesn’t get along with other pupils (R). |

| G2 Self-esteem (Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents) | TC | 6 | .81 | |

| Subscales (e.g., Global Self-Worth) | TC | 5 | .48 to .82 | Some teenagers like the kind of person they are BUT other teenagers often wish they were someone else. (TC answers either pole is “sort of” or “really true of me”) |

| G2 Positive Adjustment, W9 | Multi | 2 | .34 | |

| G2 Academic Skills | Multi | 3 | .85 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .78 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 4 | .87 (.90) | TC’s spelling performance |

| Teacher Report Form | T | 4 | .97 | TC’s language arts performance |

| Grade-point average | Records | 1 | -- | Total year grade-point average |

| G2 Peer Relations | Multi | 4 | .66 | |

| Peer Questionnaire | P | 2 | .54 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 4 | .58 (.56) | How many very good friends does your son have? |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | P | 2 | .55 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 6 | .88 (.89) | Child interacts with a number of different peers. |

| Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .43 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 4 | .61 (.59) | Doesn’t get along with other children. |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | T | 5 | .88 | What proportion of this student’s male peers like and accept him? |

| G2 Antisocial Behavior in Adolescence | Multi | 3 | .86 | |

| G2 Antisocial Behavior, W5 | Multi | 2 | .72 | |

| Antisocial | Multi | 3 | .67 | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .72 | |

| Overt Antisocial Scale | P | 2 | .73 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 7 | .81 (.78) | Child argues a lot. |

| Covert Antisocial Scale | P | 2 | .73 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 8 | .77 (.85) | Child destroys their own things. |

| Teacher Report | T | 3 | .92 | |

| Overt Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 11 | .95 | Bullies, mean to other kids |

| Covert Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 8 | .91 | Behaves irresponsibly |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | T | 1 | -- | How often does he exert a negative influence on his friends? |

| Child Interview | Mult | 3 | .71 | |

| Overt Antisocial, child phone interview | TC | 8 | .87 | In the past 24 hrs, did you disobey your parents? |

| Covert Antisocial, child phone interview | TC | 3 | .61 | In the last 3 days, did you tell a lie? |

| Child interview | I | 1 | -- | How likely TC will have future police trouble? |

| Delinquency | Multi | 4 | .70 | |

| Total arrests to date | Records | 1 | -- | Total arrests (coded 0, 1 or 2+) |

| Elliott Delinquency Scale | P | 2 | .37 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 39 | .94 (.90) | How many times in the past year has your son been disorderly in a public place? |

| Parent Questionnaire | P | 2 | .22 | |

| Mother, father report | M, F | 1 | -- | Has your son ever been picked up by the police for any reason? |

| Elliott Delinquency Scale | TC | 42 | .83 | How many times in the past year have you taken a car for a ride without permission? |

| G2 Antisocial Behavior, W7 | Multi | 2 | .73 | |

| Antisocial | Multi | 3 | .74 | |

| Parent Reports | P | 3 | .74 | |

| Overt Antisocial, Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .65 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 7 | .82 (.74) | Child physically attacks people. |

| Covert Antisocial, Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .73 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 8 | .84 (.87) | Doesn’t feel guilty after misbehaving. |

| Peer Questionnaire | P | 2 | .24 | . |

| Mother, Father Report | M, F | 1 | -- | How often conflicts with others at home? |

| Teacher Reports | T | 3 | .87 | |

| Overt Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 11 | .93 | Disrupts class discipline |

| Covert Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 8 | .86 | Disobedient at school |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | T | 1 | -- | How often does he exert a negative influence on his friends? |

| Child interview | I | 1 | -- | How likely TC will have future police trouble. |

| Delinquency | Multi | 3 | .70 | |

| Parent interview | P | 2 | .70 | |

| Mother, father | M, F | 1 | -- | Has TC done something for which he was or should have been arrested? (number of offenses) |

| Elliott Delinquency Scale | TC | 42 | .87 | How many time in the last year have you been involved in gang fights? |

| Total arrests to date | Records | 1 | -- | Total arrests (coded 0, 1, or 2+) |

| G2 Antisocial Behavior, W9 | Multi | 2 | .62 | |

| Antisocial | Multi | 4 | .55 | |

| Parent Reports | P | 3 | .79 | |

| Overt Antisocial, Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .65 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 7 | .79 (.73) | Child physically attacks people. |

| Covert Antisocial, Child Behavior Checklist | P | 2 | .72 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 8 | .82 (.85) | Doesn’t feel guilty after misbehaving. |

| Peer Questionnaire | P | 2 | .42 | |

| Mother (father) report | M (F) | 1 | -- | How often conflicts with others at home? |

| Teacher Reports | T | 3 | .85 | |

| Overt Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 11 | .88 | Disrupts class discipline |

| Covert Antisocial, Teacher Report Form | T | 8 | .75 | Disobedient at school |

| Peers and Social Skills Questionnaire | T | 1 | -- | How often does he exert a negative influence on his friends? |

| Child interview | I | 1 | -- | How likely TC will have future police trouble. |

| Activity Preferences Questionnaire | TC | 1 | -- | I enjoy being in a physical fight. |

| Delinquency | Multi | 3 | .61 | |

| Parent interview | M, F | 2 | .54 | Has TC done something for which he was or should have been arrested? (number of offenses) |

| Elliott Delinquency Scale | TC | 42 | .87 | How many time in the last year have you been involved in gang fights? |

| Total arrests to date | Records | 1 | -- | Total arrests (coded 0, 1, or 2+) |

Note. TC = G2 Target Child, M = mother, F = father, P = parent(s), I = interviewer, Multi = multiple reporting agents, R = reverse scored, α / r = internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha or Kuder-Richardson-20) for scales with >2 items; correlation for scales with 2 items.

All correlations significant (p < .05) with the exception of those marked.

Appendix B.

G2 Parenting and G3 Behavior Constructs and Measures Used in the Current Study

| Construct/Measure | Agent | Items | α / r | Sample Item |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 Constructive Parenting in Early Childhood | Multi | 2 | .56 | |

| G2 Constructive Parenting, T1 | Multi | 2 | .22 | |

| G2 Fathers’ Self-Reported Parenting | F | 3 | .51 | |

| Confident/Efficacious Discipline, Parenting Questionnaire | F | 2 | .51 | |

| Poor Implementation (R) | F | 7 | .63 | How often does your punishment depend on your mood? |

| Low Confidence (R) | F | 5 | .62 | When disciplining, how often does child ignore punishment? |

| Pleasure in Parenting Scale | F | 10 | .83 | How much do you enjoy soothing the child when they are disturbed? |

| Parent Daily Report (% positive responses) | F | 23 | -- | If child played in the last 24 hours, what did you do? |

| G2 Mothers’ Reports, Parenting Questionnaire | M | 2 | .54 | |

| Fathers’ Poor Implementation (R) | M | 7 | .60 | How often is he angry when he punishes TC? |

| Fathers’ Low Confidence (R) | M | 5 | .55 | Does he feel he has troubles managing TC generally? |

| G2 Constructive Parenting, T2 | Multi | 2 | .26 | |

| G2 Fathers’ Self-Reported Parenting | F | 3 | .62 | |

| Confident/Efficacious Discipline, Parenting Questionnaire | F | 2 | .59 | |

| Poor Implementation (R) | F | 7 | .62 | How often do you let your child get away with things that you feel should have been punished? |

| Low Confidence (R) | F | 5 | .72 | How often are you satisfied with your child’s behavior? |

| Pleasure in Parenting Scale | F | 10 | .80 | How much do you enjoy mealtimes with the child? |

| Parent Daily Report (% positive responses) | F | 23 | -- | If your child showed good manners in the last 24 hours, what did you do? |

| G2 Mothers’ Reports, Parenting Questionnaire | M | 2 | .54 | |

| Fathers’ Poor Implementation (R) | M | 7 | .69 | How often does he let TC out of a punishment when he really sets his mind to it? |

| Fathers’ Low Confidence (R) | M | 5 | .68 | How much of the time does he feel confident he can change or correct TC’s misbehavior? |

| G3 Difficult Temperament in Early Childhood | Multi | 2 | .47 | |

| G3 Difficult Temperament, T1 | M, F | 2 | .50 | |

| Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire | M (F) | 2 | .49 (.47) | |

| Activity Level | M (F) | 20 | .70 (.79) | How often did child run through the house? |

| Anger | M (F) | 28 | .90 (.89) | When you did not allow your child to do something for her/himself, how often did your child push you away? |

| G3 Difficult Temperament, T2 | M, F | 2 | .35 | |

| Children’s Behavior Questionnaire | M (F) | 5 | .67 (.62) | |

| Subscales, mother report | M | 13 | .66-.77 | Child can wait before entering into new activities if s/he is asked to (R). |

| Subscales, father report | F | 13 | .70-.75 | Child has temper tantrums when s/he doesn’t get what s/he wants. |

| G2 Constructive Parenting in Middle Childhood | Multi | 2 | .38 | |

| Constructive Parenting, T3 | F | 2 | .58 | |

| Father-Child Positive Relationship | F | 2 | .64 | |

| Child Rearing Practices Report | F | 3 | .69 | |

| Enjoyment of Child | F | 3 | .56 | It is interesting be with TC for long periods. |

| Negative Affect Toward Child (R) | F | 3 | .54 | I often feel angry toward TC. |

| Expression of Affect | F | 6 | .60 | TC and I have warm, interesting times together |

| Monitoring and Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire | F | 5 | .67 | I get along well with TC. |

| Father’s Confident/Efficacious Discipline, Parenting Questionnaire | F | 2 | .35 | |

| Poor Implementation (R) | F | 7 | .59 | How often get angry when punishing TC? |

| Low Confidence (R) | F | 5 | .63 | How often do you have to discipline TC repeatedly? |

| Constructive Parenting, T4 | Multi | 4 | .57 | |

| Fathers’ Confident/Efficacious Discipline, Parenting Questionnaire | Multi | 2 | .44 | |

| Self-Reported Parenting | F | 2 | .51 | |

| Poor Implementation (R) | F | 7 | .52 | How often do you think that the kind of punishment you give your child depends on your mood? |

| Low Confidence (R) | F | 5 | .70 | How often do you have to discipline TC repeatedly for the same thing? |

| G2 Mothers’ Reports, Parenting Questionnaire | M | 2 | .62 | |

| Fathers’ Poor Implementation (R) | M | 7 | .72 | How often do you think that he finds it hard to be patient with your child? |

| Fathers’ Low Confidence (R) | M | 5 | .77 | How often does he have to discipline TC repeatedly for the same thing? |

| Fathers’ Monitoring | Multi | 2 | .39 | |

| Monitoring, father interview | F | 4 | .77 | How often do you limit or control how much TV or movies s/he watches? |

| Monitoring, father interview | I | 1 | -- | Dad seemed to monitor TC carefully. |

| Fathers’ Involvement | Multi | 2 | .56 | |

| Self-Report | F | 3 | .64 | |

| Family Activities Questionnaire | F | 28 | .79 | In the past week, did you give child a hug or a kiss? |

| Monitoring and Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire | F | 3 | .84 | |

| Time with Child | F | 1 | -- | On average, how many days a week do you spend with your child? |

| Discussions with Child | F | 4 | .91 | How many days/week when you are taking care of your child do you talk to your child about what is happening with his/her friends? |

| Visitation Status | F | 1 | -- | How often do you see your child? (‘Live with him/her full time’ to ‘Never’) |

| Involvement, father interview | F | 4 | .59 | About how many hours on an average weekday do you talk with TC? |

| Involvement, father interview | I | 1 | -- | Dad seemed very involved in parenting? |

| Father-Child Positive Relationship | Multi | 2 | .23 | |

| Child Relationship with Parents Questionnaire | TC | 5 | .75 | Do you get along well with your dad? |

| Monitoring and Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire | F | 5 | .76 | I enjoy spending time with my child. |

| G3 Externalizing Problems in Middle Childhood | Multi | 2 | .26 | |

| Mother (Father) Report, Child Behavior Checklist | M (F) | 2 | .72 (.58) | |

| Externalizing Scale, T3 | M (F) | 2 | .60 (.61) | |

| Delinquency | M (F) | 13 | .76 (.65) | Swearing or obscene language |

| Aggression | M (F) | 20 | .90 (.86) | Destroys their own things |

| Externalizing Scale, T4 | M (F) | 2 | .68 (.66) | |

| Delinquency | M (F) | 13 | .66 (.57) | Steals at home |

| Aggression | M (F) | 20 | .89 (.88) | Physically attacks people |

Note. TC = G3 Target Child, M = mother, F = father (G2 Target), I = interviewer, Multi = multiple reporting agents, R = reverse scored, α / r = internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha or Kuder-Richardson-20) for scales with >2 items; correlation for scales with 2 items. All correlations significant.

Footnotes