Abstract

The effects of parental attitudes, practices, and television mediation on adolescent sexual behaviors were investigated in a study of adolescent sexuality and media (N=887). Confirmatory factor analyses supported an eight-factor parenting model with television mediation factors as constructs distinct from general parenting practices. Logistic regressions indicated that adolescents reporting greater parental disapproval and limits on viewing at Wave 1 were less likely to initiate oral sex between Waves 1 and 2. Adolescents who reported more sexual communication with parents were more likely to initiate oral sex. Results for vaginal intercourse were similar to those for oral sex. Co-viewing was a significant negative predictor of initiation of sexual behavior. Parental attitudes and television mediation can delay potentially risky adolescent sexual behaviors.

Keywords: Adolescent sexual/contraceptive behavior, media, parenting

Although national statistics indicate that the percentage of adolescents who report having engaged in sexual intercourse has decreased from 54% to 46% over the last decade (CDC, 2006), recent research suggests that youth may be supplanting one form of risky behavior with other potentially risky sexual behaviors such as oral sex (Mosher, Chandra, & Jones, 2005). For example, over half of adolescents aged 15 -19 (55% of males and 54% of females) report having ever had oral sex, with a significantly greater proportion of older youth reporting having engaged in oral sex (71%) relative to younger teens (43%). These data give cause for concern as research shows that oral sex places individuals at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as human papillomavirus (HPV) and gonorrhea and may also be a greater factor in HIV transmission than previously thought (Edwards & Carne, 1998; Hawkins, 2001; Robinson & Evans, 1999). Given the prevalence and potential risks associated with both oral sex and vaginal intercourse such as unwanted pregnancy and STIs, it is important to understand the psychosocial factors that are predictive of involvement in these sexual behaviors in order to design effective prevention programs.

Several decades of parent-child research have identified an extensive set of familial factors and parenting processes that influence adolescent risky behaviors and development both directly and indirectly (see Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Miller, 2002). These variables include genetic influences, structural features, parenting practices/family management, parenting style and emotional relationships. Studies have routinely found relationships between these parenting factors and adolescent sexual behaviors such as intercourse initiation and contraceptive use (see Kotchick, Shaffer, Forehand, & Miller, 2001; Meshke, Bartholomae, & Zentall., 2002; Huebner & Howell, 2003). Additionally, over 25 studies on parenting and adolescent sexuality/sexual behavior have been presented or published using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a large scale national data set with in-depth information on child-parent relationships Few studies, however, have explored the role of parental mediation of adolescent television viewing and its effect on sexual behavior. This is surprising given recent findings suggesting that sexual content on television has increased significantly over the past two decades (Brown, 2000) and adolescents' access and exposure to televised media is substantial. On average, children and adolescents watch about 21 hours per week (Roberts, 2000) [Additionally, recent evidence points to a relationship between exposure to sexual content on television and early sexual initiation among adolescents (Collins et al., 2004).

The current study builds upon previous research by examining whether parental mediation of adolescent television viewing (co-viewing, discussion of television content, limitation of viewing) comprises constructs distinct from other, more general, parenting practices such as parental monitoring and parental communication. In addition, the study examines whether and to what degree general parenting constructs and those constructs specifically related to adolescent television viewing are associated with initiation of both oral sex and vaginal intercourse in early and middle adolescence.

General Parenting Practices

Parenting practices comprise a constellation of dynamically interrelated factors including but not limited to parental supervision, affect, communication, and involvement. As suggested by Dishion and colleagues (e.g., Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Dishion, Li, Spracklen, Brown & Haas, 1998) parental influence on adolescent behavior is multifaceted and cannot be understood by isolating and focusing on a single construct, but rather by examining a broad set of factors that impact behavior. For example, parental attitudes towards sexuality cannot be effectively transmitted to adolescents without high quality parent-child communication (Weinstein & Thorton, 1987). A simultaneous examination of a comprehensive set of parenting practices and behaviors on adolescent sexual behaviors may lead to a more in-depth understanding of the factors associated with sexual initiation, which then may be applied to health promotion and pregnancy/STD prevention programs. The current study focuses on parenting practices that have previously been components of or can easily be incorporated into parenting education programs.

Perceived parental attitudes towards premarital sex and actual parental attitudes towards sexuality are strong predictors of adolescent sexual behavior. For example, several studies have found that mother's disapproval of risky sexual behavior is inversely associated with the initiation of adolescent vaginal intercourse and frequency of sexual intercourse (Davis & Friel, 2001; Jaccard, Dittus, & Gordon, 1996). Similarly, longitudinal analyses found that adolescents with higher perceived maternal disapproval of their sexual behavior were less likely than adolescents with lower levels of perceived disapproval to have vaginal intercourse during the following year (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; McNeely, Shew, Beuhring, Sieving, Miller, & Blum, 2002).

Overall quality of parental communication may also function as a protective factor. Adolescents who reported more positive communications with their parents were more likely to delay the initiation of vaginal intercourse than those who reported more negative communication with their parents (Karofsky, Seng, & Kosorok, 2000). Effective communication styles and positive parental relationships also are associated with fewer pregnancies (Barnett, Papini, & Gbur, 1991; Markham et al., 2003).

Parental communication about sex has also emerged as an important factor in the field of adolescent sexual behavior with implications for prevention programming (Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998). Findings from one longitudinal study suggested that higher levels of mother-daughter sexual risk communication were associated with a lower frequency of vaginal intercourse and more consistent contraceptive use. Mother-daughter sexual risk communication was also marginally associated with number of sexual partners (Hutchinson, Jemmot, Jemmot, Braverman, & Fong, 2003). Another study found that more comprehensive discussions about sexuality with one's mother were inversely associated with the initiation of vaginal intercourse (DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999). The research in this area, however, is equivocal (Fisher, 1993; Miller & Moore, 1990). One study using data from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health examined the effect on family structure and family context on adolescent sexual behaviors. The results showed that mothers who have more conversations with their teens about sex have children who report an earlier sexual debut, even after controlling for other parenting behaviors and adolescent socio-demographic characteristics (Davis & Friel, 2001). Several studies have noted that inconsistent findings in this area may be a result of a complex relationship between parent-child communication about sex, relationship quality, perceived parental support, and frequency of communication (e.g., Rodgers 1999) and/or variability in instrument content and sample characteristics (Fisher 1993; Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998).

Parental monitoring and supervision refers to parents' knowledge of where, how, and with whom their children spend time. Studies have found that parental monitoring is inversely associated with adolescent initiation of vaginal intercourse and total number of partners, and positively associated with contraceptive use (Small & Luster, 1994; Rodgers, 1999). For example, one study found that middle and high school students who perceived high levels of parental monitoring were more likely to have used a condom at last vaginal intercourse and to report having had only one sexual partner in their lifetime compared with adolescents who perceived low levels of parental monitoring (Huebner & Howell, 2003). A similar study found a strong inverse association between total hours of parental supervision and sexual activity (Cohen, Farley, Taylor, Martin, & Shuster, 2002). High school students who were unsupervised less than 5 hours a week (high supervision) were less likely to have had sexual intercourse and had fewer lifetime sexual partners than students who were unsupervised more than 5 hours a week. Interestingly, it appears that parental monitoring in childhood has long-term effects. Longmore, Manning, and Giordano (2001) reported that parental monitoring in late childhood delayed the initiation of sexual behavior in adolescence, even after controlling for other parenting strategies and background demographic variables.

Parental Television Mediation

Television mediation, as defined in Nathason's (2001a) review of the literature on the construct, comprises “…interactions with children about television. The interaction can take place before, during, or after viewing.” While television mediation can encompass several different behaviors, three specific constructs have been the focus of television mediation research: restrictive mediation, which refers to parental rules or limits on the amount and/or types of television content that can be viewed; co-viewing, which refers to parent-child joint viewing without discussion of content; and active mediation, which corresponds to discussion of television content (Nathanson, 2001a). It has been argued that these constructs are distinct from other parenting behaviors such as parental monitoring, discipline, and communication because they deal specifically with interactions around television whereas other parenting behaviors correspond to more general forms of interactions (Nathanson, 2001a).

Parental television mediation may directly or indirectly influence adolescent behaviors by increasing communication about sensitive subjects (e.g., drug and alcohol use, sexuality), transmitting parental attitudes, and facilitating media content assessment. A number of studies have documented demographic correlates (e.g., gender, employment status, marital status, parental education and children's age) of parental mediation behavior (e.g., Warren, Gerke, & Kelley, 2002). Additionally, several studies have found relationships among parental television mediation and their children's learning abilities, attitudes, and behavior (see Nathanson, 2001a). Early experimental work assessing the effect of different forms of active mediation on child aggression following the viewing of a movie with some violence showed that children who were in the negative-parent response active mediation condition (e.g., “That's awful”) were less aggressive than children of parents who engaged in positive active mediation (e.g., “He sure is a tough guy”) or children who did not receive any comments from parents (Hicks, 1968). Co-viewing has been also associated with aggression (Nathanson, 1999), as well as stereotyped gender role attitudes (Rothschild & Morgan, 1987). Austin and Chen (2003) found that college students who recalled more positive active mediation of media content (e.g., parents agreed with television messages, repeated things heard on television, and indicated that they liked advertised products) during adolescence had more positive attitudes towards beer advertisements, more positive alcohol-related social expectancies, and less skepticism towards advertising in general. These findings suggest that parental television mediation strategies can have both short and long term effects on children's attitudes and behavior.

In general, however, parental television mediation studies have focused primarily on parents and young children, with adolescents receiving little attention. Additionally, few studies have directly focused on behavioral outcomes, with the exception of aggression. One exception is work by Peterson et al (1991) who, using data from the National Surveys of Childern from 1976-1977 and 1981, examined whether parental co-viewing and discussion of television moderated the relationship between television viewing and vaginal intercourse among adolescents. In this study, associations between parental mediation and adolescent sexual behavior were non-significant. Given the limited attention devoted to these associations in adolescent samples, additional research is needed to explore whether and to what extent parental television mediation variables are associated with adolescent sexual behaviors, including oral sex.

The current study builds upon previous research by examining first whether parental television mediation constructs are distinct from other parenting constructs. Additionally, this study examines whether and to what extent general parenting factors (quality of overall parent-child communication, parental monitoring/supervision), parental factors specific to sex (parental communication about sex, parental sex attitudes), and parental behaviors relating to television (parental discussion of television content, co-viewing, and parental limitation of television viewing), prospectively predict the initiation of oral sex and/or vaginal intercourse in early and middle adolescence over a one year period.

Based on extant research, we hypothesize that the parental television monitoring behaviors (active, restrictive, and co-viewing) are constructs that are empirically distinguishable from other general parenting variables. Second, we hypothesize that adolescents who report conservative parental attitudes about sex, higher levels of parental supervision and communication about sex, and a more positive quality of parental communication will be less likely to initiate vaginal intercourse and oral sex over a one year period. In addition, we propose that adolescents who report that their parents place limitations on their television viewing, discuss television content, and engage in co-viewing, will also be less likely to have initiated vaginal intercourse and oral sex.

Method

Procedures

Data reported in this paper are from the first two waves of a three-wave longitudinal study targeting youth between the ages of 12 and 16 at the first survey administration. A list assisted sample of households from the greater San Francisco Bay Area (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma counties) and Los Angeles County in California was used to recruit study participants. Data collection took place over two three-month periods from September 2002 through November 2002 (wave 1) and September 2003 through November 2003 (wave 2) using Computer Assisted Self Interviews (CASIs) administered in the home. The CASI methodology has certain advantages over other survey techniques. It allows more sophisticated branching procedures making the interview process more efficient and increasing data quality. The branching capabilities also allow younger or sexually inexperienced respondents to skip over questions that are inappropriate for their age level and experience. Because the respondent interacts directly with a computer, without mediation through an interviewer, greater confidentiality can also be assured, potentially improving the validity of self-reports of sensitive behaviors (Turner, Ku, Rogers, Lindberg, Pleck, & Sonenstein, 1998; Romer, et al., 1997). Recent research suggests that adolescent respondents are much more likely to report risky behavior when they are interviewed with either web or computer based CASI measurement technology than with a paper and pencil questionnaire, particularly for more sensitive or socially undesirable attitudes and behaviors (Newman, Des Jarlais, Turner, Gribble, Cooley, & Paone, 2002; Turner et al., 1998). Data from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS, 2005) reported similar prevalence rates of sexual intercourse (25.7% of 15-17 year olds) as those we found for our most recent wave of data (26.9% of 15-17 year olds), suggesting that our data are consistent with those of other recent state studies.

Potential participants and their parents were first contacted through a mailed letter and fact sheet that described the study and invited them to take part. A follow-up telephone call was then used to schedule interviews. Up to 10 telephone contact attempts were made before a number was retired from the sample. If a household included more than one eligible individual, the youth with the most recent birthday was selected. At each in-home session, a trained interviewer explained the purpose of the survey to youth participants, showed them how to proceed through the computer program, and then left them in a private location to complete it. Additionally, parents were given a survey to complete in order to remove them from the situation. Both wave 1 and wave 2 CASIs averaged 25 to 35 minutes to complete. Active parental consent was obtained for all respondents and adolescents were given a $30 incentive to participate in each survey wave. On the basis of age, gender, and ZIP Code, sample weights were calculated using recent census data and then applied to the sample to adjust for ethnic distributions in Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Areas.

Participants

Altogether, 1,105 youth respondents completed the wave 1 survey. The adolescent survey completion rate at wave 2 was 93% (N = 1,012). In order to examine predictors of adolescent sexual initiation of oral sex and vaginal intercourse, adolescents who indicated they had engaged in either oral sex, vaginal intercourse, or both at wave 1 were deleted from the study. That is, only adolescents who were completely sexually inexperienced at Wave 1 were included in the study resulting in a final sample size of 887 respondents. The sample was nearly evenly divided between females (48%, n = 426) and males (52%, n = 461), and consisted of 106 Latinos (12%), 43 African Americans (5%), 84 Asians (including Native American and Pacific Islander, 9%), 590 European Americans (67%), 30 individuals of multiple ethnicity (3%), and 34 individuals of unknown ethnicity (4%). Based on data from Wave 2, a majority of the sample (81%, n=718) had biological parents who were living together. In addition, over 80% (n = 710) of the sample reported a total household income above $50,000.

Calculation of response rates for list-assisted surveys is complicated because eligibility cannot be determined for households in the sample that were not contacted despite extensive follow-up attempts. Therefore the CASRO method for estimating response rates was used (CASRO, 1982). Specifically, non-contacted telephone numbers were distributed between eligibles and ineligibles in the same proportions as for the numbers that were contacted. The denominator term for calculating response rate thus contains both the number of known eligible households and the estimated number of eligible households among the non-contacted numbers. Using this method, the estimated response rate was 75%. This approach is conservative because, in fact, it is likely that a greater proportion of the non-contacted numbers are ineligible (e.g., not working numbers). The cooperation rate (N completed interviews/N known eligible numbers) was considerably higher (88%) than the estimated response rate.

Measures

Background Variables, Wave 1

Respondents were asked to provide their age and gender. Respondents ranged in age from 12 to 16 years of age (M = 14.02, SD = 1.41) at wave 1. Gender was dummy coded (0=female; 1= male). Respondents were also asked to identify what racial or ethnic group(s) best described them. A dummy variable for being white was created (0 =Non-White; 1 = White). Parents who completed the Parent Self-Administered Questionnaire were asked to estimate their gross household income in 1999 before taxes. Response options ranged from less than “$15,000” (1) to over “$150,000” (9).

Parenting Items, Wave 1

Parental monitoring/supervision

Parental monitoring/supervision was a single scale consisting of three items: (a) How often do your parents or other guardians know where you are most afternoons, (b) How often do your parents or other guardians know what you do with your free time, and (c) How often do your parents or other guardians know where you are when you go out at night. Each item was scored on a four-point scale from “never know” (1) to “always know” (4) and therefore higher scores represented higher levels of parental monitoring (α = .72, M = 3.42, SD = .56).

Quality of parent-child communication

Two separate scales were used to assess quality of overall parent-child communication, one for each parent. The items in these scales were: a) My mother or female guardian (father or male guardian) and I can talk about almost anything, b) I find it easy to discuss problems with my mother or female guardian (father or male guardian), and c) When I ask questions, I get honest answers from my mother or female guardian (father or male guardian). Each item was scored on a four-point scale ranging from “never or rarely” (1) to “always” (4) with higher score representing higher quality of parent-child communication (α = .78, M = 2.97, SD= .73 for reports about mothers and α =.52, M = 2.65, SD= .83 for reports about fathers).

Parent-child communication about sex

The parental communication about sex scale was formed by the sum total of seven items. Each item was answered “yes” (1) or “no” (0), thus higher scores represent more comprehensive communication between parents and child about sexuality and sexual activities. The following items were used: In the past year have your parents or other guardians (a) Talked with you about the facts of life (sex), (b) Told you how they would feel about you having sex at your age, (c) Discussed how to say “no” when you don't want to have sex, (d) Told you not to have sex until you are married, (e) Told you that it would be best for you to have sexual experience before settling down or getting married, (f) Said that if you are going to have sex, you and your partner should use a condom, and (g) Talked with you about how to avoid getting HIV/AIDS (M = 3.58, SD = 1.95).

Parental disapproval of sex

A parental disapproval of adolescent sexuality scale was formed using three items: (a) How upset do you think your parents or other guardians would be if they found out that you made out, (b) How upset do you think your parents or other guardians would be if they found out that you had oral sex, and (c) How upset do you think your parents or other guardians would be if they found out that you had sexual intercourse. Respondents used a four-point scale from “very upset” (1) to “not at all upset” (4) to rate parents' reactions to their engaging in sexual activities. Items were recoded such that higher scores represent greater perceived parental disapproval of sex (α = .74, M = 1.61, SD = .58).

Parental mediation of television viewing, Wave 1

Respondents' perceptions of parental mediation of television viewing were assessed using eight items. Preliminary analysis indicated that these items formed three separate scales: (a) parental discussion of television content, (b) parental co-viewing, and (c) parental limitation of television viewing. Response options for each of these scales were set on a four-point scale ranging from “never” (1) to “often” (4) such that higher scores represented higher levels of parental mediation.

Discussion of television content

The parental discussion of television content scale comprised the following items: In general, how often do your parents or other guardians (a) talk with you to help you understand what you have watched on TV, (b) help you understand that some things on television are not really true, (c) tell you to watch a certain program on TV to learn more about sexuality, drugs, or other important issues, and (d) talk with you about sex that is shown or talked about on TV (α = .64, M = 1.73, SD = .57).

Co-viewing

Parental co-viewing was measured using a single item. Respondents were asked “In general, how often do your parents or other guardians watch TV with you? (M = 2.54, SD = .76) ”

Limitation of television viewing

Three items formed the parental limitation of television viewing scale: In general, how often do your parents or other guardians (a) check to see what you're watching on TV, (b) limit the amount of time you are allowed to spend watching TV, and (c) tell you that you may not watch certain programs on television (α = .67, M = 2.14, SD = .70).

Sexual behaviors, Wave 2

Oral sex and vaginal intercourse were measured with a dichotomous (yes/no) item. The CASI allowed the items to be gender specific. That is, boys were asked about their behavior with females and girls were asked about their behavior with males. For example, female participants were asked (a) “Have you ever had oral sex with a boy (when a boy puts his mouth or tongue on your genitals or you put your mouth or tongue on a boy's genitals)?”, and (b) “Have you ever had sexual intercourse with a boy? By sexual intercourse we mean when a boy puts his penis into a girl's vagina.” Parallel items focusing on oral and vaginal sex with females were asked of male respondents. Note that these items were asked at both Waves 1 and 2. However, responses at Wave 1 were used to select adolescents who had not yet participated in either vaginal intercourse or oral sex in order to be able to measure initiation of sexual behaviors.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

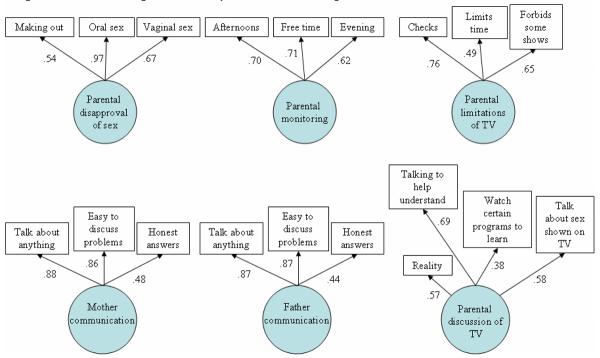

Maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) implemented with EQS 6.1 were used to verify the convergent and discriminant validity of the parenting scales and the structure underlying the scales. All 21 continuously-scaled parenting items were entered into the CFA and eight factors were specified (parental monitoring, quality of mother-child and father-child communication, parental communication about sex, parental disapproval of sex, parental discussion of TV content, parental co-viewing, and parental limitation of TV viewing). Each of the eight factors was represented by multiple items except for parental co-viewing of television and parental communication about sex, which were both single-item indicators of their corresponding constructs. Because some of the items were non-normally distributed, robust estimates of the parameter standard errors and fit statistics were obtained. All items were allowed to load only on their designated factor. In order to identify the model the loading for one item on each factor was fixed at 1.0. The factors were allowed to freely covary.

The initial specified model fit the data relatively well, Satorra-Bentler χ2 (162) = 478.75, p < .001, NFI = .91, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .045 (95% CI = .040 - .049). The LaGrange multiplier tests, however, suggested a strong correlation between the uniquenesses for two of the items from the quality of parental communication factors (When I ask questions, I get honest answers from my (a) mother or female guardian and (b) father or male guardian), χ2 (1) = 115.55, p < .001. Adding this correlation significantly improved the fit of the model: Satorra-Bentler χ2 (161) = 363.27, p < .001, NFI = .93, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .036 (95% CI = .031 - .041). No other theoretically or methodologically meaningful parameters were identified by the LaGrange tests as improving fit. All items loaded significantly on their respective factors and, for the most part, the standardized factor loading exceeded .50 (Figure 1). The exceptions were for the items, “tell you to watch a certain program on TV to learn more about sexuality, drugs, or other important issues” which loaded .37 on its factor, and, “get honest answers from my mother or female guardian (father or male guardian)” which loaded .48 and .44 respectively. Correlations among the six specified factors as well as the individual indicators of co-viewing and parental communication about sex were then computed. The correlations were generally modest suggesting that the specified factors reflected distinct constructs (see Table 1). One exception, however, was the relatively high correlation between the factors for discussion of television content and limitation of television viewing (r = .63), suggesting that these two factors could reflect facets of a single construct. In order to test this hypothesis, a model was specified combining these two factors (i.e., fixing their correlation to 1.0). A chi-square difference test indicated that the fit of the resulting seven-factor model fit was significantly worse than the eight-factor model, Δχ2 (7, N= 881) = 201.05, p <.0001, suggesting that discussion of television content and limitation of television viewing are distinct factors. Based on these analyses, scales were formed from relevant items by calculating the mean scores of the items corresponding to each of the multi-item factors.

Figure 1.

Standardized loadings for Confirmatory Factor Model of Parenting Behaviors

Table 1.

Correlations among Parenting Factors

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Parental disapproval of sex | - | |||||||

| 2. | Parental Monitoring | .170* | - | ||||||

| 3. | Parent-Child Communication (M) | .006 | .376* | - | |||||

| 4. | Parent-Child Communication (F) | .082* | .185* | .306* | - | ||||

| 5. | Co-viewing | .020 | .164* | .228* | .185* | - | |||

| 6. | Discussion of television content | .072 | .227* | .354* | .262* | .422* | - | ||

| 7. | Limitation of television viewing | .274* | .310* | .187* | .187* | .40* | .630* | - | |

| 8. | Parental communication about sex | .000 | .122* | .275* | .133* | .154* | .454* | .241* | - |

p < .05

Prior to conducting a series of logistic regressions to assess relations between parenting variables and oral sex and vaginal sex initiation, analyses of missing values (n = 802, 9%) found that a majority of missing values (n = 37) were a result of adolescents indicating that “no such person exits” in response to items about father communication. The only other item with a high non-response rate (n = 23) was for a parental communication about sex item, “Have your parents ever said if you are going to have sex you should use a condom.” A count of missing values without these two items yielded a sample size with no missing of data of 850 (96% complete). Attrition analyses revealed that adolescents with missing data did not differ from those with non-missing data in terms of age, gender, or ethnicity. However, adolescents with missing data were less likely to have had vaginal sex at wave 2 than those without missing data. Two datasets were then created, one with no missing data and one with missing data replaced using EM estimation. Logistic regressions analyses were then conducted with both datasets; however, no significant differences emerged between the two datasets. Given the lack of differences between the results from the two datasets, we report results using the more inclusive dataset with missing values replaced with EM estimation.

Preliminary analyses

Differences in parenting style at wave 1 between adolescents who reported having initiated oral sex and/or vaginal intercourse between waves 1 and 2 and those who had not were examined by testing mean group differences using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 analyses for categorical variables. Adolescents who reported having engaged in oral sex (15%) were older, perceived less parental monitoring, lower quality of mother-child communication, less parental disapproval of sex, and had parents who were less likely to mediate their television viewing (discuss TV content, co-view, and place limits on TV viewing) than adolescents who had not engaged in oral sex (Table 3). However, those engaging in oral sex reported more comprehensive communication with their parents about sex than those who had not engaged in oral sex. The results for engaging in vaginal intercourse (9%) were identical to those for oral sex, except that adolescents who reported initiating vaginal intercourse over the past year had lower incomes and reported a poorer quality of father-child communication than those who had not yet initiated vaginal intercourse.

Table 3.

Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis for Parenting Variables Predicting Initiation of Oral Sex in Adolescents (N = 887), Controlling for Background Variables

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | OR | B | SE B | OR |

| Age | 0.50** | 0.07 | 1.65 | 0.34** | 0.08 | 1.40 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.36* | 0.19 | 1.43 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 1.26 |

| Ethnicity (White) | 0.05 | 0.22 | 1.05 | -0.05 | 0.23 | 0.96 |

| Family Income | -0.02 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.00 |

| Parental monitoring | -0.32* | 0.18 | 0.72 | |||

| Quality of mother-child communication | -0.32** | 0.15 | 0.73 | |||

| Quality of father-child communication | -0.06 | 0.14 | 0.94 | |||

| Parent communication about sex | 0.18** | 0.06 | 1.20 | |||

| Parental disapproval of sex | -0.56** | 0.17 | 0.56 | |||

| Parental discussion of TV content | -0.17 | 0.23 | 0.84 | |||

| Parental co-viewing | -0.19 | 0.15 | 0.83 | |||

| Parental limitation of TV viewing | -0.55** | 0.19 | 0.58 | |||

| - 2 log likelihood | 693.91 | 639.08 | ||||

| df | 4 | 12 | ||||

| Nagelkerke's R2 | .11 | .21 | ||||

Note: Parental Monitoring/supervision scored from 1 for never know to 4 for always know, quality of parental communication scored from 1 for never or rarely to 4 for always, parental disapproval of sex scored from 1 for not at all upset to 4 for very upset, parental mediation of television items were scored from 1 for never to 4 for often. Parental communication about sex was an index with higher scores representing more comprehensive communication about sex.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Longitudinal analyses

Separate hierarchical logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine if any of the wave 1 parenting constructs predicted initiation of oral sex and vaginal intercourse at wave 2. Model 1 included age, gender, and ethnicity (white vs. non-white). Model 2 added all eight parental factors. χ2 difference tests were used to assess improvement in fit for successive models.

Oral sex

Results from the logistic regression indicate that older adolescents were more likely than younger adolescents to initiate oral sex at wave 2 (see Table 3). Ethnicity and family income did not significantly predict initiation of oral sex behavior at wave 2. However, the general parenting factors quality of mother-child communication, communication about sex, and parental disapproval of sex were significant predictors of oral sex initiation. Additionally, the parental television mediation variable parental limitation of television viewing was predictive of oral sex initiation. Youth who reported greater quality of mother-child communication, greater parental disapproval of sex, greater parental discussion of television content, and more limits on their television viewing were less likely to initiate oral sex than others. However, adolescents whose parents engaged them in more comprehensive discussions about sex were more likely to initiate oral sex between waves. Parental monitoring was moderately associated with sexual initiation. The demographic and parenting factors examined explained 21% of the variance.

Vaginal intercourse

Table 4 shows the results from the logistic regression analyses predicting vaginal intercourse initiation from parenting constructs at wave 1. The results from these analyses were substantively similar to those for oral sex with a few exceptions. Quality of mother-child communication and parental monitoring were not significantly related to initiation of vaginal intercourse. Conversely, parental co-viewing was a significant negative predictor of intercourse initiation. In addition, family income was negatively associated with sexual initiation.

Table 4.

Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis for Parenting Variables Predicting Initiation of Vaginal Intercourse in Adolescents (N= 887), Controlling for Background Variables

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | OR | B | SE B | OR |

| Age | 0.55*** | 0.10 | 1.74 | 0.41*** | 0.11 | 1.51 |

| Gender (Male) | -0.03 | 0.24 | 0.97 | -0.03 | 0.27 | 0.97 |

| Ethnicity (White) | 0.18 | 0.28 | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 1.10 |

| Family Income | -0.15** | 0.07 | 0.86 | -0.12* | 0.07 | 0.89 |

| Parental monitoring | -0.27 | 0.22 | 0.76 | |||

| Quality of mother-child communication | -0.19 | 0.19 | 0.83 | |||

| Quality of father-child communication | -0.25 | 0.18 | 0.78 | |||

| Parent communication about sex | 0.22*** | 0.08 | 1.24 | |||

| Parental disapproval of sex | -0.48** | 0.21 | 0.61 | |||

| Parental discussion of TV content | -0.20 | 0.30 | 0.82 | |||

| Parental co-viewing | -0.52*** | 0.20 | 0.60 | |||

| Parental limitation of TV viewing | -0.60** | 0.25 | 0.55 | |||

| - 2 log likelihood | 484.50 | 436.55 | ||||

| df | 4 | 12 | ||||

| Nagelkerke's R2 | .11 | .22 | ||||

Note: Parental Monitoring/supervision scored from 1 for never know to 4 for always know, quality of parental communication scored from 1 for never or rarely to 4 for always, parental disapproval of sex scored from 1 for not at all upset to 4 for very upset, parental mediation of television items were scored from 1 for never to 4 for often. Parental communication about sex was an index with higher scores representing more comprehensive communication about sex.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Again, adolescents whose parents were believed to be more disapproving about sex, co-viewed television shows, and limited their television viewing were less likely to initiate vaginal intercourse than others. Consistent with the results for oral sex, youth who reported that their parents had engaged them in more comprehensive discussions about sexuality were more likely to have engaged in vaginal intercourse for the first time between Waves 1 and 2. Together, demographic and parenting factors examined explained 23% of the variance in the outcome.

Exploratory analyses

An additional set of analyses were conducted to determine if gender or socioeconomic status moderated the relationships between parenting constructs and sexual initiation of either oral sex or vaginal intercourse by using sets of relevant interaction terms (e.g., parental monitoring x gender, parental monitoring x SES) as predictors in parallel pairs of logistic regression models (one model including gender interaction terms only, one model including SES interaction terms only) for each outcome variable.. No interaction term was significantly related to initiation of sexual behavior, and inclusion of these sets of interaction terms did not significantly improve the fit of the models. Comparisons of coefficients from models estimated on male-only and female-only sub-samples revealed no significant gender differences.

As discussed above, parental communication may interact with other parenting behaviors such that a preventive effect of communication will occur only when other parenting behaviors are present. Analyses were conducted to explore interactive effects between parental communication about sex and other parenting factors. We estimated two logistic regression models in which seven interaction terms (e.g., parental monitoring x parental communication about sex, parental disapproval of sex x parental communication about sex) were used to predict initiation of vaginal intercourse and oral sex. The results suggest that a complex interaction between parental communication about sex and co-viewing (OR = .77, p < .01) in predicting initiation of vaginal intercourse. Specifically, adolescents who had low levels of parental communication about sex and low levels of co-viewing and adolescents who had high levels of parental communication about sex and high levels of co-viewing were less likely to have initiated vaginal intercourse than others. No other interaction terms were significant.

Discussion

Results from the confirmatory factor analysis suggest that parental television mediation constructs are empirically distinct from general parenting constructs and are significant predictors of adolescent sexual behaviors. These are important findings, as they suggest another area that prevention programs can target to affect adolescent sexual behavior. In longitudinal analyses predicting initiation of oral sex and vaginal intercourse, similar patterns of results were obtained across the two behaviors for background variables and the set of parenting variables considered. Consistent with previous research, age was positively associated with the initiation of sexual behavior while perceived parental disapproval of sex was inversely related to adolescents' sexual behavior. Contrary to expectations, parental communication about sex was positively associated with initiation of both oral and vaginal sex. One possible explanation for this finding is that parents who anticipated that their children would soon become sexually active (or youth who are thinking about becoming sexually active) were more likely to engage in discussions about sexual issues.

A concrete understanding of parent-child communication about sex, however, is complicated by differences in perceived and actual communication. Newcomer and Udry (1985) reported that parents and children disagreed about the occurrence of sex-related communication, as mothers were more likely to report having taught their children “things about sex” than children were to report being taught about sex. In addition, adolescents who indicate that they talked with their parents about “how to say no when you don't want to have sex” could be referring to two very different experiences. For example, parents may tell their child, “you cannot have sex until you are married so if it comes up just say no.” On the other hand, parents may talk to their child about a number of refusal skills that their child could employ in various situations. Without directly assessing what transpired, it is difficult to accurately determine how parental communication affects adolescent sexual behavior, which may account for these contradictory findings (see Lefkowitz, 2002).

Exploratory analyses focusing on parental communication found an interactive effect of parental communication about sex and co-viewing. Specifically, adolescents who had low levels of parental communication about sex and low levels of co-viewing and adolescents had high levels of parental communication about sex and high levels of co-viewing were less likely to have initiated vaginal intercourse than others. These findings suggest that parents who watch television with their children may be taking advantage of unique “teaching moments.” That is, they may have the opportunity to discuss sexual behavior and consequences of sexual behaviors using scenarios raised by television content. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study which found that adolescents who watched a Friends episode about condom failure and talked about it with an adult were more likely to report learning about condoms from the episode and indicate that condoms were more effective than they previously believed than other viewers (Collins, Elliot, Berry, Kanouse, & Hunter, 2003). Together these findings indicate that prevention programs consider incorporating the use of popular teen television programs into their curriculum as a method of having parents talk to their children about sex.

Parental television mediation strategies were also predictive of changes in adolescents' sexual behavior. Specifically, parental limitation of television viewing was negatively associated with both sexual behaviors. Parental co-viewing was inversely related to vaginal intercourse initiation only. While not all parental mediation variables were predictive of sexual behaviors, the odds ratios were in the expected direction. These findings are consistent with those of other media researchers who have found that active mediation (discussing television with youth) and restrictive mediation (establishing rules about how much, when, and which types of television content can be viewed) have been associated with a variety of positive outcomes among youth such as increased comprehension of television (Collins, Sobol, & Westby, 1981; Desmond, Singer, Singer, Calam, & Colimore, 1985), skepticism toward televised news (Austin, 1993), and less generalized as well as television-induced aggression (Nathanson, 1999). Findings on co-viewing (watching television together without discussion), however, have been mixed. However, it is unclear why parental television mediation variables have differential effects on specific types of adolescent sexual behaviors.

In addition to increasing youths' critical viewing skills and making them less vulnerable to negative television effects, media researchers have speculated that parental mediation strategies may help communicate important parental attitudes to children about the value of television, how it should be used, and how much attention it merits (Nathanson, 1999). For example, it has been suggested that parents who have discussions with their children about television, discount or contradict negative messages that appear on television, and establish limits on television viewing, may be sending messages to children that the discussed or prohibited content is not important, is not useful to social learning, and is not worthy of their attention. Evidence suggests that co-viewing in the absence of active mediation sends children the opposite messages about television. In her research on elementary school children and their parents, Nathanson (2001b) found that children make inferences about parental attitudes as a function of mediation strategies employed, so that co-viewing with restrictive mediation was interpreted by children as a sign that parents did not like violent content. In contrast, co-viewing without mediation was perceived by children as an endorsement of the co-viewed violent material. Along with the findings on parental disapproval, these findings on parental mediation strategies provide additional evidence of the importance of parental attitudes in influencing adolescent sexuality.

Despite the commonly held belief that parental influence wanes substantially as youth reach adolescence, the findings from the current study suggest several ways in which parents continue to play an important role in their child's behavior well into adolescence. Given that the assessed variables accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in the outcomes, these findings suggest that parents have considerable influence on their adolescents' sexual behavior. As the outcome of interest was sexual behavior, it is not surprising that parental behaviors and attitudes directly associated with sex were the strongest parenting predictors. In addition, parents' strategies for intervening in their youths' television viewing and their overall monitoring of youths' behavior were significantly related to youth sexuality. These findings are consistent with a national survey of 15 to 17 year olds regarding their decision making about sex and relationships. This study showed that 80% of youth reported that they were influenced some or a lot by “what parents have told them” and 79% reported being influenced some or a lot by “what parents might think” (Kaiser Family Foundation and Seventeen Magazine, 2000). More than nine of 10 of these teens agreed that among the benefits of waiting to have sex is enjoying the respect of parents. Thus, although teens may often give the appearance of tuning out parents and following their peers, parents should be encouraged to make their attitudes, expectations, and feelings about youth sexual behavior known.

A recent review of adolescent sexuality programs that incorporate a parental component reported that a total of 19 programs were available nationwide, with great variability existing among these programs with regards to target audience, time commitment, and delivery methods. (Meshke et al., 2002). While many of these programs have addressed general parenting and sexuality-specific parenting practices, parental mediation of television viewing has not been a focus of these programs. Given that youth watch an average of 21 hours of television per week (Roberts, 2000), and the high level of sexual content on television (Brown et al., 2000), parental mediation of television viewing would seem to be an intervention target that could significantly influence adolescent sexual behavior. For example, joint parent-child viewing of sexual content on television could serve as an impetus for family discussions about sex and provide opportunities for parents to express their attitudes and values regarding youth sexuality. In practice, materials on television mediation could provide parents with information about how they can be proactive in countering the effects of televised depictions of sex on youth. Strategies such as limiting television viewing and engaging youth in discussions about televised sexual content could serve both to undermine sex-promoting messages from television and to convey messages that are consistent with parental attitudes.

The current study has several limitations related to generalizability of the findings. First, a majority of the sample identified as white. Although minorities were included in the study, the numbers for each non-white ethnic group were relatively small and were collapsed into one group and therefore the ability to make ethnic comparisons was limited. Previous research suggests that ethnicity is an important factor in determining media consumption, interpretation, and use. For example, African Americans have been found to spend more time watching television, be more likely to choose fictional programming with African American characters, and perceive fictional characters to be more realistic than their Caucasian peers do (Dates, 1980; Greenberg, 1993; Gruber & Thau, 2003; Steele, 2002). Similarly, African Americans report watching more videos (Steele, 2002) and R-rated movies with less parental involvement or mediation than do whites. Though we were unable to assess if general parenting and parental television mediation behaviors were differentially predictive of adolescent sexual initiation behaviors across different ethnic groups, we were able to determine whether mean parenting scores differed by ethnicity. Few significant differences emerged, but the results did show that Hispanic youth reported significantly greater parental communication about sex than Whites and Asians. Asian youth reported more conservative parental attitudes about sex than Whites, and Hispanics reported greater discussion of television content than whites. Future studies in this area should strive to oversample minority youth to facilitate cross-ethnic comparisons. We controlled for family income, but in general the income level among the sample was relatively high compared to the national average. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to some populations. Another potential limitation of the current study is its focus on heterosexual adolescent sexual behavior. Future studies should assess whether and to what extent parenting behaviors differentially impact homosexual adolescent sexual behaviors. Also, we did not take into account the role of other potentially important parenting factors such as family composition. While family composition has the potential to influence adolescent sexual behavior, it was our intent in the current paper to focus on parenting behaviors that can easily be and often are targeted for change by prevention programs.

Other limitations have to do with measurement of study variables. First, the parent questionnaire did not parallel the youth survey, and thus we were only able to collect youth self-report data on perceived parenting behaviors, which may be biased. Data triangulation (e.g., reports on behavior from several sources: parents and youth) should be used in future research to overcome inherent biases resulting from single report data collection. Also, for some parenting factors, corresponding survey items did not specify whether the perceived attitude or behavior was mother- or father- focused. As such, we were unable to disentangle separate effects for each parent. Finally, some of the predictor variables showed modest levels of internal consistency. Low reliability could partially explain non-significant relations between these predictors (e.g., quality of father communication, discussion of television content) and the outcomes. Despite these limitations, we suggest that these findings make an important contribution to the literature as they highlight the importance of general parenting and sex-specific parenting practices as well as parental mediation of television practices on adolescent sexual behaviors.

Over a decade of research has documented the relationship between parenting factors and adolescent sexual behaviors. However, this is one of the first studies to examine parental mediation of television and its effects on adolescent sexual behaviors. The current study also suggests potentially important directions for future research on the relationship between parental mediation of media and adolescent sexual behaviors. Given ethnic differences in media consumption, parenting practices, and parental attitudes towards sexual behavior, future studies should consider how the association between parental mediation of television and video content might differ across ethnic groups. Also, nearly all participants (95%) in the current study reported having Internet access in the home and nearly half had access to the Internet in their bedrooms. With the high prevalence of sexual content on the Internet, it becomes increasingly important to understand how parents can effectively mediate the content of this medium and how this may influence adolescent sexual behaviors.

Table 2.

Mean Differences (SD) in Parenting Predictors Between Initiators and Non-initiators for Oral Sex and Vaginal Intercourse (N = 887)

| Oral Sex | Vaginal Intercourse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No (85%) | Yes (15%) | No (91%) | Yes (9%) |

| Age | 14.75*** (1.40) | 15.71 (1.44) | 14.80*** (1.44) | 15.85 (1.23) |

| Female, % | 49.6% | 41.4% | 48.2% | 50.0% |

| Male, % | 50.4% | 58.6% | 51.8% | 50.0% |

| Ethnicity (White), % | 65.8% | 69.9% | 66.1% | 69.2% |

| Ethnicity (Non-white), % | 34.2% | 30.1% | 33.9% | 30.8% |

| Family Income | 6.74 (1.78) | 6.75 (1.93) | 6.78** (1.78) | 6.35 (2.02) |

| Parental monitoring | 3.45*** (0.55) | 3.21 (0.60) | 3.44*** (0.55) | 3.21 (0.65) |

| Quality of mother-child communication | 3.00*** (0.72) | 2.78 (0.75) | 2.99*** (0.73) | 2.78 (0.76) |

| Quality of father-child communication | 2.66 (0.83) | 2.57 (0.80) | 2.67*** (0.83) | 2.43 (0.83) |

| Parent communication about sex | 3.53* (1.98) | 3.83 (1.79) | 3.54*** (1.96) | 3.99 (1.82) |

| Parental disapproval of sex | 3.45*** (0.56) | 3.07 (0.64) | 3.42*** (0.57) | 3.08 (0.64) |

| Parental discussion of TV content | 1.76*** (0.56) | 1.57 (0.57) | 1.75*** (0.57) | 1.53 (0.53) |

| Parental co-viewing | 2.57*** (0.74) | 2.38 .80 | 2.57*** (0.75) | 2.22 (0.73) |

| Parental limitation of TV viewing | 2.20*** (0.70) | 1.79 .63 | 2.18*** (0.70) | 1.71 (0.62) |

Note: Parental Monitoring/supervision scored from 1 for never know to 4 for always know, quality of parental communication scored from 1 for never or rarely to 4 for always, parental disapproval of sex scored from 1 for not at all upset to 4 for very upset, parental mediation of television items were scored from 1 for never to 4 for often. Parental communication about sex was an index with higher scores representing more comprehensive communication about sex. Parenting items are based on data collected at Wave 1.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant Number HD038906 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of NICHD or NIH.

References

- Austin EW. Exploring the effects of active parental mediation of television content. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1993;37:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Chen YJ. The relationship of parental reinforcement of media messages to college students' alcohol-related behaviors. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8(2):157–69. doi: 10.1080/10810730305688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JK, Papini DR, Gbur E. Familial correlates of sexually active pregnant and non-pregnant adolescents. Adolescence. 1991;26(102):458–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD. Adolescents' sexual media diets. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(2):35–40. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey . Data and findings. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2005 from http://www.chis.ucla.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- CDC National Risk Youth Behavior Survey 1991-2005: Trends in the Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors. 2006 Retrieved July 7, 2006, from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/2005_YRBS_Sexual_Behaviors.pdf.

- Council of American Survey Research Organizations On the definition of response rates: a special report of the CASRO task force on completion rates. 1982 Retrieved August 1, 2003, from http://www.casro.org/resprates.cfm.

- Cohen DA, Farley TA, Taylor SN, Martin DH, Shuster MA. When and where do youths have sex? The potential role of adult supervision. Pediatrics. 2002;111(6):1–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e280–e289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sobol BL, Westby S. Effects of adult commentary on children's comprehension and inferences about a televised aggressive portrayal. Child Development. 1981;52:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliot MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Hunter SB. Entertainment television as a healthy sex educator: The impact of condom-efficacy information in an episode of Friends. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1115–1121. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dates J. Race, racial attitudes, and adolescent perceptions of Black television characters. Journal of Broadcasting. 1980;24(4):549–560. [Google Scholar]

- Davis EC, Friel LV. Adolescent sexuality: Disentangling the effects of family structure and family context. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:669–681. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond RJ, Singer JL, Singer DG, Calam R, Colimore K. Family mediation patterns and television viewing: Young children's use and grasp of the medium. Human Communication Research. 1985;11:461–480. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Li F, Spracklen K, Brown G, Haas E. Measurement of Parenting Practices in Research on Adolescent Problem Behavior: A Multimethod and Multitrait Analysis. In: Ashery RS, Robertson EB, Kumpfer KL, editors. Prevention Through Family Interventions. NIDA Research Monograph 177, U.S Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. pp. 260–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental Monitoring and the Prevention of Problem Behavior: A Conceptual and Empirical Reformulation. In: Ashery RS, Robertson EB, Kumpfer KL, editors. Prevention Through Family Interventions. NIDA Research Monograph 177, U.S Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. pp. 229–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents' perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:268–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Carne C. Oral sex and the transmission of viral STIs. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 1998;74:6–10. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TD. An extension of the findings of Moore, Peterson, and Furstenberg (1986) regarding family sexual communication and adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;51(3):637–639. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg BS. Race differences in television and movie behaviors. In: Greenberg BS, Brown JD, Buerkel-Rothfuss NL, editors. Media, Sex and the Adolescent. Hampton Press; Cresskill, NJ: 1993. pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber EL, Thau H. Sexually-related content on television and adolescents of color: Media theory, physiological development, and psychological impact. Journal of Negro Education. 2003;72:438–456. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D. Oral sex and HIV transmission. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2001;77:307–308. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.5.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks DJ. Effects of co-observer's sanctions and adult presence on imitative aggression. Child Development. 1968;39:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Cooney TM. Patterns of parent-teen sexual communication: Implications for interventions. Family Relations. 1998;47(2):185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmot JB, Jemmot LS, Braverman P, Fong G. The role of mother-daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon VV. Maternal correlates of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28:159–165. 185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Seventeen Magazine Decision making: A series of national surveys of teens about sex. 2000 September; Retrieved February 15, 2005, from http://www.kff.org/youthhivstds/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageI D=13538/

- Karofsky PS, Seng L, Kosorok MR. Relationship between adolescent-parental communication and initiation of first intercourse by adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;28:41–45. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R, Miller KS. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(4):493–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES. Beyond the yes-no question: measuring parent-adolescent communication about sex. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2002;97:43–56. doi: 10.1002/cd.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC. Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens' dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Vol. 4. Wiley; New York: 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Escobar-Chaves SL, Parcel GS, Harrist R, Addy RC. Family connectedness and sexual risk-taking among urban youth attending alternative high schools. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35(4):174–179. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.174.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely C, Shew ML, Beuhring T, Sieving R, Miller BC, Blum RW. Mothers' Influence on the Timing of First Sex Among 14- and 15-Year-Olds. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(3):256–265. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshke LL, Bartholomae S, Zentall SR. Adolescent sexuality and parent-adolescent processes: Promoting healthy teen choices. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:264–279. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC. Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):22–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Moore KA. Adolescent sexual behavior, pregnancy, and parenting: Research through the 1980s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1025–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 362. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2005. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: Men and women 15-44 years of age, United States, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Identifying and explaining the relationship between parental mediation and children' aggression. Communication Research. 1999;26(2):124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Mediation of children's television viewing: Working toward conceptual clarity and common understanding. Communciation Yearbook. 2001a;25:115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Parent and child perspectives on the presence and meaning of parental television mediation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2001b;45(2):201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer SF, Udry JR. Parent-child communication and adolescent sexual behavior. Family Planning Perspectives. 1985;17(4):169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JC, Des Jarlais DC, Turner CF, Gribble J, Cooley P, Paone D. The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(2):294–297. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Moore KA, Furstenberg FF. Television viewing and early initiation of sexual intercourse: Is there a link? Journal of Homosexuality. 1991;21(12):93–118. doi: 10.1300/J082v21n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout VJ. Generation M: Media in the lives of 8 to 18 year olds. Kaiser Foundation; Palo Alto, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EK, Evans BG. Oral sex and HIV transmissions. AIDS. 1999;13:737–738. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904160-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers KB. Parenting processes related to sexual risk-taking behaviors of adolescent males and females. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Hornick R, Stanton B, Black M, Li X, Ricardo I, Feigelman S. “Talking” computers: A reliable & private method to conduct interviews on sensitive topics with children. Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild N, Morgan M. Cohesion and control: Adolescents' relationships with parents as mediators of television. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1987;7:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent sexual activity: An ecological, risk factor approach. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Steele JR. Teens and movies: Something to do, plenty to learn. In: Brown JD, Steele JR, Walsh-Childers K, editors. Sexual Teens, Sexual Media: Investigating Media's Influence on Adolescent Sexuality. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren R, Gerke P, Kelly MA. Is there enough time on the clock? Parental involvement and mediation of children's television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2002;46(1):87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Thorton A. Mother-child relations and adolescent sexual attitudes and behavior. Demography. 1989;26(4):563–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]