Abstract

Many college entrants’ parents do not have college degrees. These entrants are at high risk for attrition, suggesting it is critical to understand mechanisms of attrition relative to parental education. Moderators and mediators of the effect of parental education on attrition were investigated in 3,290 students over 4 years. Low parental education was a risk for attrition; importantly, college GPAs both moderated and mediated this effect, and ACT scores, scholarships, loans, and full-time work mediated this effect. Drug use, psychological distress, and few reported academic challenges predicted attrition, independent of parental education. These findings might inform interventions to decrease attrition.

College attrition has been characterized as a national concern for many years because it creates major impediments to upward social mobility and economic success (Brown, 1960; Horn, Berger & Carroll, 2004). For example, the yearly income of college graduates far exceeds that of individuals with some college ($45,221 as opposed to $31,936; U.S. Census Bureau, 2006a), a disparity that affects many given that 19.5% of the population of individuals in the United States who are 25 years and older attempted college but did not obtain a degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006b). Because enrollment in degree-granting institutions is predicted to increase from the 17.3 million who enrolled in 2004 to 19.9 million enrolling in 2015 (Hussar & Bailey, 2006), these increased numbers of future enrollees are likely to be at risk for attrition if current educational attainment statistics hold over time. Thus, it is of utmost importance to understand the phenomenon of attrition such that informed efforts can be made to decrease the rate of its occurrence.

General theories of attrition are typically longitudinal, assuming a causal timeline, and integrate a number of student background characteristics and collegiate experiences as factors that predict attrition (Astin, 1993; Braxton, Hirschy, & McClendon, 2004; French & Oakes, 2004; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1980; Tinto, 1993). Student background or college entry factors occur first on the timeline and are referred to as time-fixed, most typically measured at one point in time. Factors that describe the college experience are apt to change over the course of a college career and are referred to as time-varying, most optimally assessed over multiple measurement occasions. Also of note, this timeline arrangement of factors implies processes of mediation and moderation. That is, student characteristics (time-fixed factors) give way to the college experience (time-varying factors), and therefore, the college experience factors may, in fact, be intervening factors that explain the association between particular student characteristics and attrition (mediation) or affect the strength of the association between a particular student characteristic and attrition (moderation). Ultimately then, it becomes quite clear that general theoretical models of attrition are meant to evoke specific questions, such as: What particular types of student characteristics are most predictive of attrition? What particular types of subsequent college experiences do these student characteristics predict that would then later predict attrition?

Figure 1 adapts a largely cited general model of attrition (Tinto, 1993) to a very specific set of individuals, namely students whose parents do not have college degrees (i.e., first-generation students). The level of a student’s parents’ education is a student characteristic of particular interest, as it can either provide a unique advantage, or a unique disadvantage, to a student’s own academic attainment. That is, parents who have college degrees may have familiarized their children at early ages with college life and expectations, creating an advantage for their college-bound children. Parents who do not have college degrees might be comparatively unfamiliar with (or even disdainful of) college life and expectations, creating a disadvantage for their children who aspire to attain a college education (Bui, 2002; Chen, 2005; Nuñez, Cuccaro-Alamin, & Carroll, 1998; Warburton, Bugarin, Nuñez, & Carroll, 2001). Indeed, nationally representative educational statistics show that, among students whose parents had bachelor’s degrees or higher, 10.0% withdrew from college over the first year of enrollment at 4-year institutions, but among students whose parents had high school diplomas or lower, 23.4% withdrew (Horn & Carroll, 1998). Moreover, it is estimated that approximately one third of college entrants’ parents do not have college degrees (Nuñez et al.), meaning that there are a large number of students who are particularly at risk for attrition simply on the basis of the level of their parents’ educations.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model of Attrition in First-Generation Students

Adapted From Tinto (1993)

In addition to the relevance of parents’ level of education (and subsequently, parents’ support for educational attainment) to attrition (McCarron & Inkelas, 2006), there are a number of factors apparent just prior to and during college that are associated with both lower levels of parental education and, also, attrition from college. Therefore, these factors can easily fit within a model of student departure that is tailored to first-generation students (please see the factors shown in bold in Figure 1). For example, upon entry to college, first-generation students generally report feeling less academically prepared for college and, in fact, have lower college entrance exam scores and lower aspirations for degree attainment in comparison to their peers; these three factors are strongly associated with attrition from college (Bui, 2002; Horn & Nuñez, 2000; Terenzini, Springer, Yaeger, Pascarella, & Nora, 1996). Also, first-generation students often report that they lack funds to pay for their education (Bui). Notably, self-reported lack of funds is a well established correlate of attrition (Tinto, 1993). Perhaps to counter a lack of funds, first-generation students often hold jobs while in college (Pascarella, Pierson, Wolniak, & Terenzini, 2004). In many cases, part-time jobs can be beneficial by enhancing students’ abilities and interests and potentially directing students toward post-college job opportunities (Tinto). However, first-generation students are likely to have full-time jobs, which have been found to correlate strongly with attrition (Billson & Terry, 1982) purportedly because it is quite difficult to manage both the demands of a full-time job as well as college work. Indeed, in comparison to their peers, first-generation college students tend to have lower college grade-point averages (GPAs), a strong correlate of attrition (Pantages & Creedon, 1978; Warburton et al., 2001).

At the same time, in college students forge social relationships with other students. Heavy alcohol use is recognized as an ambient part of many social events on college campuses and has been related to attrition (Martinez, Sher & Wood, 2008); such a case may also hold for drug use (Mohler-Kuo, Lee, & Wechsler, 2003). Substance use may be particularly relevant as far as risks to first-generation college students, because social events and atmospheres at college (including those that endorse substance use) are extremely novel for them (Bui, 2002). Of note, however, the association between low parental education, substance use, and subsequent attrition has not yet been well studied (but see Wood, Sher, Erickson, & Debord, 1997). Given that first-generation students must quickly adapt to what for them may be novel social climates and academic demands, it is not surprising that first-generation college students report having more academic and social challenges than their peers, where reports of having such challenges have been shown to presage attrition (Bui, French & Oakes, 2004; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1980). Being in such a challenging atmosphere may also increase general psychological distress in first-generation students, which can be common in college youth and is associated with attrition from college (Brackney & Karabenick, 1995). Though Figure 1 leaves room for a host of other potential factors, low academic preparation, low college aspirations, lack of funds, full-time job status, substance involvement, low college GPA, self-reported challenges in college, and psychological distress have been specifically hypothesized (and for the most part, empirically shown) to be associated with both low parental education and attrition. Thus, these factors appear to be the most relevant for understanding the relation between low parental education and subsequent attrition behavior.

In summary therefore, we know that low parental education predicts attrition. However, we know that many other factors occur over time that relate both to low parental education and to attrition. Furthermore, such factors might explain why and how low parental education is such a deleterious risk factor, a rationale for study that is evident in both early and recent work on first-generation students and academic performance (Pratt & Skaggs, 1989; Strayhorn, 2006). That is, these factors of attrition might moderate or mediate the effect of low parental education on attrition. Moderation means that the effect of low parental education on attrition varies as a function of a “third” or intervening variable. Thus, factors that moderate the effect of parental education on college attrition have the potential to identify subgroups of first-generation students who are most at risk for attrition. For example, academic preparation might be considered as a “third” or moderating variable, whereby first-generation students who are not academically prepared might be at risk for attrition, whereas first-generation students who are well prepared might not be at risk.

It is also important to investigate whether these factors of attrition mediate the effect of low parental education on attrition. Mediation means that the effect of low parental education on attrition is explained by a “third” or intervening variable that occurs subsequent in time to the risk factor of low parental education. That is, low parental education predicts a number of college-entry and experience factors; of note, these factors also predict attrition and, if they are found to mediate the effect of low parental education on attrition, they explain why first-generation students are at risk for attrition. Thus, these factors are foci for intervention because, if they are modified, they would hopefully decrease the occurrence of attrition in first-generation students. For example, low college GPA might be considered a “third” or mediating variable that explains the association between low parental education and attrition. In this case, low college GPA would be a more potent predictor of attrition than low parental education. Therefore, interventions to improve first-generation students’ GPAs would likely decrease their rates of attrition.

Thus, determining moderation and mediation effects aids in understanding the construct of parental education beyond its current status as a simple index of student advantage or disadvantage for two reasons. First, it can allow the public (e.g., researchers, administrators, clinicians, students and parents) a more complex understanding of the potential factors involved in the relation between parental education and attrition, many of which might occur while a student is in college and when arrangements can be made to aid students. Second, therefore, identification of mediators and moderators can inform future interventions for decreasing attrition rates.

However, even the most exhaustive longitudinal studies of parental education and attrition have not yet examined moderating and mediating effects (Ishitani, 2003, 2006). This is partly because it has been most relevant thus far to find appropriate statistical methods to model attrition, a highly nonlinear phenomenon (DesJardins, Ahlburg, & McCall, 2002; Ishitani, 2003, 2006). This is also partly because of a “lack of available time-varying items in the study data” (Ishitani, 2006, p. 865) to capture college experience-related factors that predict attrition.

Because attrition is a complex phenomenon, it is highly likely that the effect of low parental education on attrition is both moderated and mediated by a host of other factors. Thus, we estimated whether and how a number of factors that have been shown to be correlated with parental education and have also been shown to predict attrition (i.e., low academic preparation, low college aspirations, lack of funds, full-time job status, substance involvement, low college GPA, self-reported challenges in college and psychological distress, as shown in Figure 1) may in fact be mediating and moderating factors of the overall relation between parent education and attrition over 4 years at a large Midwestern public university.

METHOD

A sample of 3,720 first-time college students (88% of the 2002 entering class, where the initial sampling target included all entering first-time college students for that school year) was surveyed the summer prior to entry to a large Midwestern public and research extensive university (Wave 0), following approval from the university Institutional Review Board. Participants were then assessed using an online survey at each successive semester for eight semesters (Waves 1–8) over 4 years.

Participants

At Wave 0, 28.7% of the sample had parents who did not have college degrees, 53.6% were female, and the sample averaged 17.96 (SD = 0.37) years of age. The racial composition was as follows: 90.3% were White/non-Hispanic, 4.8% were Black/non-Hispanic, 2.8% were Asian, 1.6% were Hispanic, and 0.5% were Native American/American Indian. Of this sample, 90.0% participated in two or more assessment waves. Retention biases were minimal and reported in other work (Sher & Rutledge, 2007); of note, steady participants were comparatively more likely to be female (OR = 2.33) and have higher combined college entrance exam scores and high school class ranks (OR = 1.27). Participants were excluded from analyses if they reported transferring to a different university (n = 424). An additional 6 participants were not included in the analyses, never having fully matriculated at the university. Thus, a total of 3,290 participants were ascertained for the present analyses.

Measures

Parental Education

This variable was dichotomous and provided by the university registrar. The registrar requires each college applicant to answer the following question: “Prior to your 18th birthday, did either of your parents have a college degree?” (0 = Yes, 1 = No). Ancillary analyses, available from the first author, demonstrate that findings based on this registrar’s measure of parental education were very similar to findings based from a stricter measure of parental education, ascertainable from n = 1,855 of the sample, namely, whether or not both parents had no more education than a high school diploma.

Attrition (Nonenrollment)

This was the dependent measure, provided by the university registrar. As such, there was no missing information with regard to this variable. Non-enrollment was dichotomously assessed at each semester (0 = Enrolled, 1 = Nonenrolled).

Time

Students’ enrollment status was assessed each semester over 4 years for a total of eight measurement occasions. Time was used as a covariate in all analyses, and its parameterization in the analyses will be described in detail in the data analysis section.

Factors of Attrition: College Entry Characteristics

The following time-fixed factors were assessed either prior to college entry, or at the first semester of college: academic preparation, college aspirations and lack of funds.

ACT composite scores and high school rank percentile scores, both provided by the university registrar, were used to assess academic preparation, as they are widely accepted indices of this construct (Stumpf & Stanley, 2002).

At the summer before entry to college (Wave 0), participants endorsed various reasons for attending college (1 = Not at all important, 2 = Somewhat important, 3 = Important, 4 = Very important). Four different college aspirations were identified from composites of these items. The college–party aspiration asked the importance of: attending college to have fun, fraternities/sororities, and parties (α = .65). The college–edification aspiration asked the importance of: attending college to learn, to broaden perspectives, to attain feelings of accomplishment, and to develop interpersonal skills (α = .74). The college–career aspiration asked the importance of attending college to get a more satisfying job and to increase earning potential (α = .68). The college–date/mate aspiration asked the importance of: attending college to meet a boyfriend/girlfriend and to find a spouse (α = .81). Although the party and date–mate aspirations are not directly related to general academic aspirations, they fit well into conceptualizations of the college experience and academic and social integration, which are relevant to first-generation students and attrition (Pratt & Skaggs, 1989); they have, therefore, been included for exploratory value.

Lack of funds for college was assessed at the first semester. Students were asked if they were paying for college by using each of the following sources of financial support: scholarships, grants, loans, parents, off-campus job, on-campus job, savings/stocks/bonds, and military benefits (0 = Yes, 1 = No). Separately, each item indicates a student’s use of a particular method to pay for college; there is no consideration of whether a student is using several methods to pay for college, nor is there an indication of a general lack or presence of funds. However, these items were included together as covariates in analyses. Thus, the effect of each form of funding on attrition was estimated while controlling for all other sources of funds. Therefore, the scale for the effect of each item is rendered: 0 = Presence of a specific type of fund while controlling for other sources of funds, 1 = Lack of a specific type of fund while controlling for other sources of funds. Of note, because first-generation students are often in need of funds, they are also more likely to apply for and have scholarships and loans; however, this does not indicate that first-generation students have no lack of funds (Nuñez et al., 1998). Rather, it indicates the importance of considering a number of different sources of funding simultaneously.

Factors of Attrition: College Experience

The following time-varying factors were assessed over the course of the college experience: job status, college semester GPAs, heavy alcohol use, drug use, academic challenges, social challenges and psychological distress.

Each semester, students were asked their job status—whether they had any job, or were working part-time or full-time. These responses were coded into a set of categorical variables in order to assess the potential beneficial effects of working at all or working part-time (Tinto, 1993) as well as to assess the hypothesized negative effects of working full-time. Thus, the first variable dichotomously assessed whether a student had a job (0 = No job, 1 = Has a job). The second factor was dummy-coded to assess the effect of part-time (0 = No job, 1 = Part-time) and full-time (0 = No job, 1 = Full-time) work against having no job. Of note, at the first semester, participants reported that they did not have a job, had either an on- or off-campus job, or had both an on- and off-campus job, rather than reporting that they either had no job, worked part-time or worked full-time, as they reported at each subsequent semester. However, prior to becoming a set of categorical variables, the first semester ordinal variables were found to be internally consistent with those at the other time-points (α = .83).

Each semester, college semester GPAs were provided by the university registrar and were on a 4.0 scale.

Each semester, heavy alcohol use was assessed as a composite of three 9-point ordinal scales asking the number of occasions per week in the past month that students drank five or more drinks in a sitting, felt high, and got drunk on alcohol (α = .92 to .93 across all time-points; 0 = Did not in the past 30 days, 1 = Once in the past 30 days, 2 = 2–3 times in the past 30 days, 3 = Once or twice a week, 4 = 3–4 times a week, 5 = 5–6 times a week, 6 = Nearly every day, 7 = Every day, 8 = Twice a day or more; Sher & Rutledge, 2007).

Each semester, drug use was assessed as a composite of seven 8-point ordinal scales assessing the number of occasions in the past 3 months that students took the following classes of drugs: stimulants and amphetamines, psychedelics, barbiturates, opiates, and cannabis (α = .69 to .78 across all time-points; 0 = Never used, 1 = Used but not in the past three months, 2 = One time in the past three months, 3 = 2–5 times, 4 = 6–10 times, 5 = 11–20 times, 6 = 21–40 times, 7 = more than 40 times). Participants were instructed not to include any drugs that had been prescribed to them by a physician.

Each semester, academic challenges were assessed by a measure asking students the degree to which “academics” had been a challenge so far while attending college. Similarly, social challenges were assessed by a measure asking students the degree to which “developing and maintaining friendships” had been a challenge so far while attending college (0 = Not at all, 1 = A little bit, 2 = Moderately, 3 = Quite a bit, 4 = Extremely).

Each semester, psychological distress was assessed using raw scores of the Global Severity Index from the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2000), an 18-item self-report assessment of psychological symptoms (α = .90). Participants can endorse the degree to which a number of symptoms (e.g., loneliness, hopelessness, panic, nausea, restlessness, nervousness) has affected them in the past week on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all, 1 = A little bit, 2 = Moderately, 3 = Quite a bit, 4 = Extremely). Of note, only 17 of the 18 items were included, as the item assessing suicidal intention was deleted and replaced with a filler item.

Demographic Variables

Sex and race were selected as control variables in the analyses as there is evidence that sex and race are correlated with parental education, such that low parental education is associated with being female and of an underrepresented racial background (Nuñez et al., 1998). Sex was dichotomous (0 = Female, 1 = Male). The overwhelming majority of students (90.3%) were White/non-Hispanic, which is representative of the university; thus, for the purposes of these analyses, race was simply dichotomized into a Caucasian (White/non-Hispanic) group and a non-Caucasian or racially underrepresented group (0 = White/Non-Hispanic; 1 = Underrepresented).

Data Analysis

Discrete time event–history analysis was used to address study hypotheses. Event–history techniques model the probability or hazard of a given event over time and are similar to logistic regression, though these techniques are specifically for analyses of longitudinal data (Allison, 1984; Yamaguchi, 1991). The dataset was configured into a person–semester record of events in which data were recorded for each person at each semester. The event that students could experience, in this case attrition from college, was recorded when and if it occurred, and all event data thereafter were not included (note that only three individuals left prior to completing the first semester). Of note, no event data was recorded for individuals reporting having graduated prior to completing 4 years of study (n = 109) at the time point that they reported graduating and thereafter. Thus, first-time nonenrollment at college was modeled as the dependent variable. Analyses of another variation of nonenrollment (i.e., permanent nonenrollment, defined as nonenrollment with no subsequent return over the 4 years) using these data produced findings similar to those presented here and are available from the first author.

Time was measured using four different parameters to account for the nonlinear effects found in attrition research, specifically, that risk for attrition increases over the first year, with the highest nonenrollment rates observable just after the first year, at the sophomore fall semester, and then attrition decreases thereafter (DesJardins et al., 2002; Ishitani, 2003, 2006). Thus, the sophomore fall semester will hereafter be referred to as the time of “greatest observable nonenrollment” (GONE). The first time parameter was a linear variable in which the zero point was centered at the time of GONE. Thus, the coding of the eight semesters for this parameter ranged from −2 to 5. The second time parameter was a dummy variable comparing attrition at the first year against all other years (1 = First year semesters, 0 = All other semesters). The third parameter was a dummy variable comparing fall semester attrition with spring semester attrition (0 = Fall semesters, 1 = Spring semesters). The fourth parameter was an interaction between the two dummy variables to again account for the time of GONE, which occurs at the fall semester, just after the first year.

The hypothesis that factors of attrition moderate the effect of parental education on attrition from college was addressed through tests of statistical interaction. Specifically, we estimated two-way interactions between parental education and the individual factors of attrition in models predicting nonenrollment. Each factor of attrition was individually modeled with parental education because preliminary analyses revealed collinearity between factors of attrition, complicating interpretation of complex multivariate models.

The hypothesis that the factors of attrition mediate the effect of parental education on attrition from college was addressed using a well established statistical method (Baron & Kenny, 1986), which can be applied to the conceptual model in Figure 1. First, the effect of parental education on each of the individual factors of attrition was estimated (referred to as “a” paths; as noted above, each factor of attrition was individually modeled, rather than modeled in a multivariate framework). For each of the time-varying factors, mixed linear regression models were used to account for within-person correlation of items across time. Second, the effect of each of the individual factors on attrition was estimated (referred to as “b” paths). A requirement of mediation was that the corresponding “a” and “b” paths be statistically significant. Also, and more importantly, mediation requires that the predictive effect of low parental education on attrition be attenuated with the inclusion of the “third,” or intervening, factor of interest (i.e., the individual factors of attrition) into the predictive model. Mediated effects were estimated by taking the product of the effects of the “a” and “b” paths, and they were tested using a Sobel-like (Sobel, 1982) formula for logistic regression procedures (this method is reported in MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993, and MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, first-generation students differed from their peers on a number of factors. Specifically, they had lower ACT scores, yet modestly higher high school class rank scores, which may be confounded somewhat with high school academic intensity level and high school class size (Ishitani, 2006). They reported fewer aspirations to “party” in college than did other students, and they reported higher aspirations to attend college to increase career opportunities. They also reported lower aspirations to find a mate in college.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Information and Group Differences

| First-Generation Students (n = 921) |

Non-First-Generation Students (n = 2,369) |

Group Differences (n = 1,928– 3,289) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | Odds Ratio |

|

Entry Characteristics | |||||

| ACT Composite Score | 25.11 | 3.40 | 26.00 | 3.40 | 0.93** |

| high School Rank | 78.99 | 17.07 | 76.66 | 19.01 | 1.01** |

| Party Aspiration | 2.53 | 0.70 | 2.66 | 0.70 | 0.78** |

| Edification | 3.32 | 0.53 | 3.31 | 0.53 | 1.00 |

| Career Aspiration | 3.68 | 0.47 | 3.64 | 0.53 | 1.19* |

| Date/Mate Aspiration | 1.57 | 0.73 | 1.77 | 0.80 | 0.72** |

| Lack of Funds From (%) | |||||

| Scholarships | 27.02 | 34.12 | 0.81* | ||

| Grants | 59.12 | 80.38 | 0.52** | ||

| Loans | 38.33 | 61.27 | 0.51** | ||

| Parents’ Contribution | 28.71 | 18.66 | 1.54** | ||

| Off-Campus Job | 83.88 | 87.13 | 0.87 | ||

| On-Campus Job | 80.06 | 88.93 | 0.80 | ||

| Savings | 77.09 | 70.99 | 1.36** | ||

| Military | 98.59 | 99.27 | 0.54 | ||

|

College Experience | |||||

| Job Status (%) | |||||

| Work at All | 32.96–80.93 | 22.32–70.77 | 1.71**–1.93** | ||

| Part-Time Work | 29.84–71.67 | 20.69–65.74 | 1.66**–1.89** | ||

| Full-Time Work | 1.45–13.23 | 0.71–9.29 | 2.20**–2.78** | ||

| College GPA | 2.89–3.49 | 0.73–4.55 | 3.01–3.43 | 0.66–3.14 | 0.77**–1.00 |

| Heavy drinking | 1.30–1.46 | 1.23–1.32 | 1.41–1.59 | 1.26–1.31 | 0.90*–0.97 |

| Drug Use | 0.22–0.25 | 0.51–0.61 | 0.23–0.27 | 0.46–0.59 | 0.92–1.05 |

| Academic Challenges | 1.67–2.28 | 1.02–1.26 | 1.69–2.24 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.95–1.06 |

| Friendship Challenges | 0.79–1.05 | 0.98–1.12 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.96–0.59 | 0.87**–1.09 |

| BSI 18 Global Severity Index | 0.40–0.54 | 0.51–0.60 | 0.44–0.52 | 0.53–0.58 | 0.85–1.12 |

Note. Sex and race controlled in sex difference analyses. Means based on sex and race are available from first author.

p < .05.

p < .01.

After controlling for the other sources of funding, first-generation students were found to be less likely to report having a lack of funding from scholarships, grants, and loans; that is, first-generation college students were more likely to report using these sources of funding to pay for college. Conversely, they were more likely to report a lack of funding with regard to parental contributions and savings. We were able to assess other college experience variables at each semester of college. For example, first-generation students were more likely than were their peers to work in college and to work part-time jobs at all times during college, and they were even more likely to have full-time jobs. Also, they tended to have lower college GPAs in comparison to their peers. First-generation students tended to drink less heavily than did their counterparts in college, perhaps as they were also more likely to be in underrepresented racial groups (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.69), and heavy drinking rates are often found to be somewhat lower in underrepresented racial groups of college students (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002). Interestingly, first-generation students also tended to report having fewer friendship problems then did their peers.

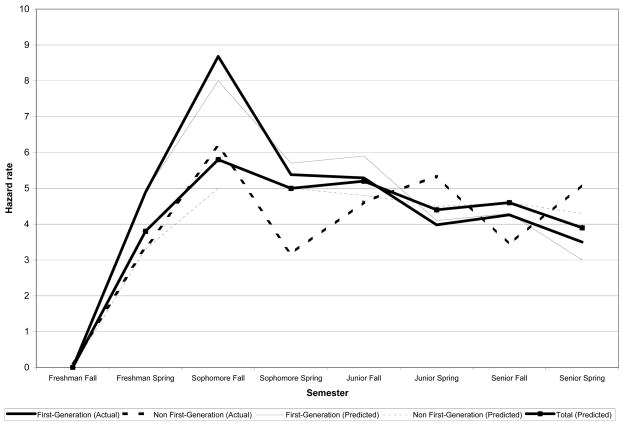

With regard to attrition, first-generation students were more at risk than their peers (β = .20, SE = .07, p < .01), though nonenrollment was rather high for all students; the prevalence of nonenrollment at each semester ranged from 4.9% to 25.8% for first-generation students and 0.1% to 19.2% for their counterparts. Overall, as shown by cumulative prevalence rates in Figure 2, 30.6% of first-generation students and 27.1% of their peers had left college at least once in 4 years, clearly prolonging their time to graduation, if not permanently leaving college. As shown by hazard rates in Figure 3 (where hazard rates are defined as the probability of nonenrollment at a given semester among participants who did not already leave college at the previous semesters), most students were at risk for leaving at the time of GONE, similar to findings elsewhere (Ishitani, 2003, 2006).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative Prevalence Rates of First Nonenrollment

FIGURE 3.

Hazard Rates of First Nonenrollment

Moderation Effects

Despite the hypothesis that many factors of attrition would moderate the effect of low parental education on attrition, only one moderation effect (statistical interaction) was found. Specifically, GPA interacted with parental education to predict nonenrollment, such that the simple effect of having low GPAs was larger (i.e., more deleterious) for first-generation students than for their peers (β = −1.42, SE = .07, p < .01 vs. β = −1.23, SE = .05, p < .01).

Mediation Effects

Although there was only one moderation effect, Table 2 shows that ACT composite scores (partially), scholarships, loans, job status and college GPAs individually acted as potential mediators of the relation between low parental education and attrition in single mediator models. That is, these factors were related to parental education as well as attrition. Additionally, they attenuated the effect of low parental education, either partially or to nonsignificance, and their mediator effects were also statistically significant. Therefore, in general, these factors can be hypothesized to represent mechanisms of attrition that underlie the low parental education/attrition relation.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Mediator Effects on First NonEnrollment (Un-Standardized Parameter Estimates)

| Step 1: Parental Education Predicting Mediators (a Paths)a |

Step 2: Mediators Predicting First-Semester Not-Enrolled (b Paths)b |

Resulting Effect of Parental Education on First-Semester Not-Enrolled |

Mediator Effects |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediators | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | Z |

|

Entry Characteristics | |||||||||

| ACT Composite Score | −0.83** | .13 | −0.06** | .01 | 0.16* | .07 | 0.05 | .01 | 4.40** |

| High School Rank | 2.07** | .71 | −0.02** | .01 | 0.28** | .08 | −0.05 | .02 | −2.84* |

| Party Aspiration | −0.12** | .03 | −0.01 | .05 | 0.20** | .07 | 0.01 | .01 | 0.23 |

| Edification | −0.01 | .02 | 0.02 | .06 | 0.20** | .07 | −0.01 | .01 | −0.04 |

| Career Aspiration | 0.04* | .02 | −0.16** | .06 | 0.20** | .07 | −0.01 | .01 | −1.67 |

| Date/Mate Aspiration | −0.18** | .03 | −0.09* | .04 | 0.18* | .07 | 0.02 | .01 | 1.95 |

| Lack of Funds From | |||||||||

| Scholarships | −0.31** | .01 | 0.62** | .09 | 0.13 | .10 | −0.20 | .07 | −2.90** |

| Grants | −1.03** | .10 | −0.12 | .11 | 0.12 | .11 | 1.08 | ||

| Loans | −0.93** | .09 | −0.20* | .09 | 0.19 | .09 | 2.15** | ||

| Parents’ Contribution | 0.55** | .10 | 0.11 | .10 | 0.06 | .06 | 1.11 | ||

| Off-Campus Job | −0.28* | .03 | 0.10 | .13 | −0.03 | .04 | −0.75 | ||

| On-Campus Job | −0.68** | .12 | 0.03 | .13 | −0.02 | .09 | −0.19 | ||

| Savings | 0.30** | .10 | 0.03 | .10 | 0.01 | .03 | 0.32 | ||

| Military | −0.66 | .43 | −0.89** | .34 | 0.58 | .44 | 1.33 | ||

|

College Experience | |||||||||

| Job Status: | |||||||||

| Work at All | 0.81** | .09 | −0.71** | .16 | −0.12 | .20 | −0.57 | .02 | −3.89** |

| Part-Time Work | 0.54** | .08 | −1.36** | .20 | −0.19 | .19 | −0.73 | .02 | −4.88** |

| Full-Time Work | 0.82** | .14 | 1.44** | .21 | 1.18 | .07 | 4.46** | ||

| College GPA | −0.10** | .02 | −1.30** | .04 | 0.03 | .08 | 0.13 | .03 | 4.55** |

| Heavy drinking | −0.12* | .05 | 0.04 | .06 | −0.20 | .19 | −0.01 | .01 | −0.60 |

| Drug Use | −0.01 | .02 | 0.23* | .11 | −0.20 | .19 | −0.01 | .01 | −0.21 |

| Academic Challenges | 0.03 | .03 | −0.60** | .08 | −0.22 | .19 | −0.02 | .02 | −1.00 |

| Friendship Challenges | −0.02 | .03 | 0.09 | .07 | −0.21 | .19 | −0.01 | .01 | −0.62 |

| BSI 18 Global Severity Index | −0.01 | .02 | 0.40** | .12 | −0.26 | .20 | −0.01 | .01 | −0.05 |

Note. Sex and race controlled in all analyses. Time parameters are covariates in all steps. PRoC MIXEd (continuous variables)/GLIMMIX (dichotomous variables) effects are given for a-paths of time-varying variables.

n = 2,371–3,289); n(person-semesters) = 16,009–23,711.

n(person-semesters) = 15,730–23,018.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The meaning of some of these mediated effects requires more detailed explanation, particularly with regard to lack of funds and job status. Regarding lack of funds, first-generation students were more, rather than less, likely than their peers to have scholarships. But lacking, rather than having, a scholarship denoted risk for attrition (while controlling for the other types of sources of funding for college). Because the first-generation students in this case more often had (rather than lacked) scholarships, the algebraic sign of the mediated effect is negative, which is statistically permissible in mediation (MacKinnon, Krull & Lockwood, 2000). What is most important to note is that lacking (rather than having) scholarships predicted attrition and, accounting for sources of funding in the predictive model, attenuated the effect of low parental education on attrition to nonsignificance. Thus, the valid conclusion is that the lack of a scholarship is a comparatively more potent predictor of attrition than low parental education.

With regard to loans, first-generation students had more loans than their peers, and having more loans predicted attrition; therefore having (rather than lacking) a loan is the predictive mechanism of attrition, over low parental education. With regard to job status, it was found that first-generation students work more in general and in both part-time and full-time jobs. Working in general and working part-time were protective factors, rather than risk factors of attrition. In contrast, full-time work clearly predicted attrition. Despite this distinction, collegiate work status appears to be a potential mediator of the effect of low parental education on attrition on all counts. Lastly, it should be noted that although psychological distress, and also reportedly having few (as opposed to more) academic challenges, did not meet full criteria for being mediators (as they did not specially relate to parental education), they predicted attrition and attenuated the effect of low parental education on attrition to nonsignificance.

DISCUSSION

Our findings are consistent with other studies that have indicated that first-generation students are at risk with regard to completing college (Ishitani, 2003, 2006; Warburton et al., 2001). Yet, almost one third of current college entrants are first-generation students, both in our findings and in nationally representative samples (Nuñez et al., 1998). Thus, it is critical to know what processes underlie this risk in order to identify key targets for interventions to decrease attrition rates.

Our findings showed some modest differences between first-generation students and their peers. Though some of the differences may indicate vulnerabilities for this group (e.g., they had lower college entrance exam scores and lower GPAs in college), many of these differences are remediable through interventions (Braxton et al., 2004). Also, first-generation students were not more likely than their peers to demonstrate psychological distress and drug and alcohol involvement, meaning that this group is not at risk in all realms relevant to low academic success.

The fact that only one of the hypothesized factors moderated parental education status indicates that the hypothesized factors of attrition were not uniquely deleterious for first-generation students alone. Furthermore, the fact that relevant factors of attrition mediated the negative and highly unalterable effect of low parental education indicates that effective modification of these factors through intervention studies could possibly decrease attrition rates for these at-risk students. For example, although low parental education predicts attrition, low parental education also predicts full-time work in college, which precedes the occurrence of attrition on the timeline. Our findings indicate that full-time work mediates or explains the association between low parental education and attrition. Thus, if an intervention were to occur that would decrease first-generation students’ propensity for full-time work, we would potentially also decrease first-generation students’ propensity for attrition.

Thus, with regard to interventions for first-generation students, the present study indicates that directed efforts towards improving financial, academic, and job-related concerns should continue to be highly encouraged. Examples of potentially helpful interventions that address such a purpose for this risk group are summer bridge programs (i.e., preparatory workshops and classes given in the summer), intensive financial and academic advising services for students, and academic learning communities that promote students’ development of adaptive academic skills (Thayer, 2000). It is prudent to focus mainly on improving financial and academic concerns given how conceptually challenging it may be to target this risk group. The challenge arises because the identity of a student whose parents do not have a college education (i.e., a student who is inherently not fully integrated into the college atmosphere), if overly regarded, may stigmatize a student within the college setting (Orbe, 2004). Stigmatization can impair academic performance through “stereotype threat,” by which individuals perform more poorly than they would have otherwise on a given task when potentially negative stereotypes relevant to their demographic characteristics are made salient (Steele, 1997). Thus, when disseminating the aforementioned academic interventions, campuses might avoid stigmatization by ensuring that terms such as “first-generation students,” “blue-collar scholars” and “FGEN students” are used with positive connotation (especially where use of the term would have the potential to instill sense of community, collaboration, and also achievement and pride at being the first in one’s family to go to college) and are not just used as identifiers of risk or disparity. Academic interventions should stress the idea that they help students build on existing skills (e.g., the skills that gained new matriculates entry into college), never giving students the impression that they have fewer inherent skills than other students or that they have any less inherent ability of earning a college degree than their peers. Related to this idea, one should avoid exhibiting great surprise or disdain towards students who do not appear to know college procedures (like those involved in completing college financial forms, registering for classes, or submitting assignments). Showing surprise or disdain might inadvertently suggest to a first-generation student that he or she is quite academically and financially different from his or her peers and, given the negative reaction, possibly not as deserving of a college education. Thus, administrators, financial officers, and faculty members should provide as much procedural information as possible to students, doing so in a neutral manner.

It is important to note that attrition is a problem for students in general; 27.1% of the students in the study whose parents had college degrees were nonenrolled at least once over 4 years. A number of variables that failed to mediate the relation between low parental education and attrition, such as fewer aspirations to enhance one’s career, fewer (rather than more) reported academic challenges, drug use in college, and psychological distress, nevertheless generally predicted withdrawal from college. Thus, these factors should not be ignored with regard to intervention for the general student body (Braxton et al., 2004; Tinto, 1993).

Limitations

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, many other possible factors of attrition might be assessed (e.g., selectivity of the institution, family pressures and responsibilities, and medical issues). Second, the measurement of some of the variables could be improved in future studies (i.e., the financial variables were crudely assessed at one time point from student reports). Also, the aspirational measures were not available at every time point, and they had mildly low levels of internal consistency, though it should be noted that these variables are viewed as being based upon causal rather than effect indicators, rendering internal consistency a less important psychometric index for these composite variables. Still, it would be useful to refine the aspiration variables in future studies. Third, these mediators are potential mediators only; they represent theoretically consistent findings, but true mediators can be determined only from experimental studies, which modify factors (mediators) to determine changes in outcomes. Fourth, because the study ended after 4 years (due to funding constraints) and the median time to degree is now more than 4 years (Horne, 2006), we were not able to measure attrition that occurs beyond the fourth or senior year.

Additionally, it should be noted that this is a single-campus study. Given the specific aspects of the study institution, a large, 4-year public and research extensive Midwestern university that is fairly homogeneous in regard to student races and ages, caution should be taken in attempting to generalize findings across all campuses. In particular, this study found relatively small (though significant) differences in attrition rates based on students’ parents’ education in comparison to what was found in other studies (Ishitani, 2003, 2006; Warburton et al., 2001), perhaps partly as a result of some of the aforementioned unique characteristics of this university. Additionally, the high salience of financial, job-related, and academic factors as mediators for this sample may be different at more elite private colleges, which may present both different opportunities and challenges to students. Similarly, the role of other factors as mediators might differ slightly across campuses, given different campus recruitment demographics (e.g., religious, performing arts, historically Black, or women’s colleges) and established campus programs and regulations. Multicampus studies would allow researchers to examine how the types of individual characteristics identified here interact with institutional characteristics to predict attrition rates.

Future Directions

Despite the immensity of the problem of college attrition, there is a dearth of studies that prospectively account for a large number of both student background and college experience variables with regard to the level of students’ parents’ education. Future research might examine departure combined with reentry into college. Future interdisciplinary research pursuits involving psychological and educational correlates of the college experience and attrition are suggested. Furthermore, randomized, controlled field trials that evaluate the efficacy of modifying factors of attrition, both individually and in combination with each other, on nonenrollment are needed to inform policy on how best to reduce attrition in general and for those most at risk. Such an undertaking is extremely costly and time consuming, but the potential benefits of improving retention are great for students, institutions of higher learning, and the nation at large.

Contributor Information

Julia A. Martinez, Doctoral student in the Department of Psychology, University of Missouri–Columbia

Kenneth J. Sher, Curators’ Professor of Psychology, University of Missouri–Columbia

Jennifer L. Krull, Associate Professor of Quantitative Psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles

Phillip K. Wood, Professor of Quantitative Psychology, University of Missouri–Columbia

References

- Allison PD. Event history analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Astin AW. What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social-psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billson JM, Terry MB. In search of the silken purse: factors in attrition among first-generation students. College and University. 1982;58(1):57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brackney BE, Karabenick SA. Psychopathology and academic performance: The role of motivation and learning strategies. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(4):456–465. [Google Scholar]

- Braxton JM, Hirschy AS, McClendon SA. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report. 3. Vol. 30. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004. Understanding and reducing college student departure. [Google Scholar]

- Brown NC, editor. Higher education: Incentives and obstacles. Washington, DC: American Council on Education; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bui KT. First-generation college students at a four-year university: Background characteristics, reasons for pursuing higher education, and first-year experiences. College Student Journal. 2002;36(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. First generation students in postsecondary education: A look at their college transcripts (NCES 2005–171) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The brief symptom inventory-18 (BSI-18): Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins SL, Ahlburg DA, McCall BP. A temporal investigation of factors related to timely degree completion. Journal of Higher Education. 2002;73(5):555–581. [Google Scholar]

- French BF, Oakes W. Reliability and validity evidence for the institutional integration scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004;64(1):88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Horn L, Berger R, Carroll CD. College persistence on the rise? Changes in 5-year degree completion and postsecondary persistence rates between 1994 and 2000 (NCES 2005–156) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Horn LJ, Carroll CD. Stopouts or stayouts? Undergraduates who leave college in their first year (NCES 1999–087) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Horn LJ, Nuñez AM. Mapping the road to college: First-generation students’ math track, planning strategies, and context of support (NCES 2000–153) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Horne WW, editor. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 1 Vol. 53. 2006. Almanac Issue [Special Issue] [Google Scholar]

- Hussar WJ, Bailey TM. Projections of education statistics to 2015 (NCES 2006–084) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani TT. A longitudinal approach to assessing attrition behavior among first-generation students: Time-varying effects of pre-college characteristics. Research in Higher Education. 2003;44(4):433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani TT. Studying attrition and degree completion behavior among first-generation college students in the United States. Journal of Higher Education. 2006;77(5):861–885. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JA, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is heavy drinking really associated with attrition from college?: The alcohol-attrition paradox. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:450–456. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron GP, Inkelas KK. The gap between educational aspirations and attainment for first-generation college students and the role of parental involvement. Journal of College Student Development. 2006;47:534–549. [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M, Lee JE, Wechsler H. Trends in marijuana and other illicit drug use among college students: Results from 4 Harvard School of Public Health college alcohol study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52(1):17–24. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez AM, Cuccaro-Alamin S, Carroll CD. First-generation students: undergraduates whose parents never enrolled in postsecondary education (NCES 98–082) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbe MP. Negotiating multiple identities within multiple frames: An analysis of first-generation college students. Communication Education. 2004;53(2):131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pantages TJ, Creedon CF. Studies of college attrition: 1950–1975. Review of Educational Research. 1978;48(1):49–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella ET, Terenzini PT. Predicting freshman persistence and voluntary dropout decisions from a theoretical model. Journal of Higher Education. 1980;51(1):60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella ET, Pierson CT, Wolniak GC, Terenzini PT. First-generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. Journal of Higher Education. 2004;75(3):249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt PA, Skaggs CT. First generation college students: Are they at greater risk for attrition than their peers? Research in Rural Education. 1989;6:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist. 1997;52(6):613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn TL. Factors influencing the academic achievement of first-generation college students. NASPA Journal. 2006;43:82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf H, Stanley JC. Group data on high school grade point averages and scores on academic aptitude tests as predictors of institutional graduation rates. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2002;62(6):1042–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Terenzini PT, Springer L, Yaeger PM, Pascarella ET, Nora A. First-generation college students: characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Research in Higher education. 1996;37(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer PB. Retention of students from first generation and low income backgrounds. Opportunity Outlook. 2000 May;:2–8. ERIC ED446633. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto V. Leaving college: rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2006 American Community Survey: Median Earnings in the Past 12 months. 2006a Retrieved September 22, 2007, from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-mt_name=ACS_2006_EST_G2000_B20004.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2006 American Community Survey: Educational Attainment. 2006b Retrieved September 22, 2007, from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S1501&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_.

- Warburton EC, Bugarin R, Nuñez AM, Carroll CD. Bridging the gap: Academic preparation and postsecondary success of first-generation college students (NCES 2001–153) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK Sher KJ, Erickson DJ, Debord KA. Predicting academic problems in college from freshman alcohol involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(2):200–210. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K. Event history analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]