Abstract

Background:

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) was started in 2004. Presently, 58% of the 198 hospitals participating in ACS-NSQIP are academic or teaching hospitals. In 2008, ACS-NSQIP initiated a number of changes and made risk-adjusted data available for use by participating hospitals. This analysis explores the ACS-NSQIP database for utility in developing hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgery-specific outcomes (HPB-NSQIP).

Methods:

The ACS-NSQIP Participant Use File was queried for patient demographics and outcomes for 49 HPB operations from 1 January 2005 through 31 December 2007. The procedures included six hepatic, 16 pancreatic and 23 complex biliary operations. Four laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy operations were also studied. Risk-adjusted probabilities for morbidity and mortality were compared with observed rates for each operation.

Results:

During this 36-month period, data were accumulated on 9723 patients who underwent major HPB surgery, as well as on 44 189 who received cholecystectomies. The major HPB operations included 2847 hepatic (29%), 5074 pancreatic (52%) and 1802 complex biliary (19%) procedures. Patients undergoing hepatic resections were more likely to have metastatic disease (42%) and recent chemotherapy (7%), whereas those undergoing complex biliary procedures were more likely to have significant weight loss (20%), diabetes (13%) and ascites (5%). Morbidity was high for hepatic, pancreatic and complex biliary operations (20.1%, 32.4% and 21.2%, respectively), whereas mortality was low (2.3%, 2.7% and 2.7%, respectively). Compared with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the open operation was associated with higher rates of morbidity (19.2% vs. 6.0%) and mortality (2.5% vs. 0.3%). The ratios between observed and expected morbidity and mortality rates were <1.0 for hepatic, pancreatic and biliary operations.

Conclusions:

These data suggest that HPB operations performed at ACS-NSQIP hospitals have acceptable outcomes. However, the creation of an HPB-NSQIP has the potential to improve quality, provide risk-adjusted registries with HPB-specific data and facilitate multi-institutional clinical trials.

Keywords: cholecystectomy, hepatectomy, hepaticojejunostomy, pancreatectomy, quality

Introduction

The concept of a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) originated in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 In response to a law passed by the United States Congress, a National VA Surgical Risk Study (NVASRS) was planned in 1991. The NVASRS prospectively collected data on major operations at 44 VA hospitals and developed risk-adjusted models for 30-day morbidity and mortality for eight surgical specialties.2,3 Using this experience, the VA-NSQIP was established in1994 at all 132 VA medical centres. Over the next few years, VA-NSQIP was able to demonstrate a 45% reduction in morbidity, a 27% decrease in mortality and major cost savings.4

In 1999 surgeons at three university hospitals joined the VA programme as an alpha test of NSQIP in the private sector. Again, NSQIP was demonstrated to reduce morbidity, mortality and cost at university hospitals.5 This success led to the Patient Safety in Surgery (PSS) Study submitted by the American College of Surgeons and funded from 2001 to 2004.6 The PSS was conducted in 128 VA medical centres as well as in 14 university beta sites and covered major general and vascular surgery. Data were collected on over 145 000 general and 39 000 vascular operations. Thirty-day unadjusted mortality for men was significantly lower in the private sector (2.03% vs. 2.62%; P < 0.001).7

In 2004 the American College of Surgeons (ACS) initiated ACS-NSQIP. By December 2008, 198 hospitals were receiving ACS-NSQIP feedback on their surgical outcomes and reliable data on over 350 000 operations had been accumulated. However, 58% of the participating hospitals were larger academic or teaching centres and only a small percentage of smaller community hospitals were involved. In addition, the majority of the data represented a random sample of all general and vascular operations. Therefore, in an effort to improve ACS-NSQIP, a number of modifications were recommended.8 These recommendations include: (i) establishing multiple specialty-specific modules; (ii) 100% sampling of selected procedures; (iii) establishing a limited set of generic and more procedure-specific patient characteristics; (iv) setting a focus on procedure-specific outcomes; (v) the addition of processes of care measures; (vi) the reporting of procedure- and surgeon-specific outcomes, and (vii) the incorporation of hierarchical modelling techniques for lower-volume programmes. In 2008 ACS-NSQIP established a Participant Use File, which houses data on all patients in the programme from 2005 to 2007. The aim of this analysis was to explore the ACS-NSQIP database for utility in developing hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgery-specific outcomes (HPB-NSQIP).

Materials and methods

American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

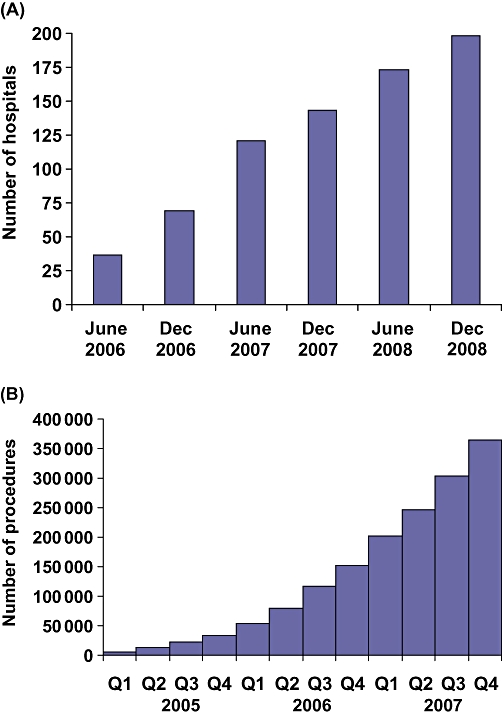

Over the first 4 years of its existence, the ACS-NSQIP has grown significantly. By December 2008, 198 hospitals were entering data and receiving risk-adjusted outcomes (Fig. 1A). The majority of these hospitals were large; 49% of them had more than 500 licensed beds and 33% had 300–499 beds. ACS-NSQIP employs a systematic sampling process which uses an 8-day cycle whereby the first 40 cases to fulfil inclusion and exclusion criteria at each participating hospital are randomly selected. The vast majority of major operations are acceptable for inclusion in ACS-NSQIP every 8 days. Exclusions include: (i) minor cases; (ii) cases with subjects aged under 16 years; (iii) more than five inguinal hernias or breast lumpectomies per 8-day cycle; (iv) trauma and transplant operations, and (v) American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class 6 cases. ACS-NSQIP presently includes general and vascular surgery or, for lower-volume hospitals, a multispecialty option (cardiac, gynaecological, neurological, orthopaedic, otolaryngological, plastic, thoracic and urological surgery). Outcomes are assessed at 30 days after the index operation and highly standardized and validated data definitions are employed.

Figure 1.

(A) Number of hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). (B) Number of procedures recorded in the ACS-NSQIP Participant Use File

Surgical clinical nurse reviewers (SCNRs) are trained and certified, and receive continuing education as well as ongoing support. For each patient or operation, 136 variables are collected. Preoperative data include six demographic, 44 clinical and 13 laboratory variables. Intraoperative data include 11 operative, 16 clinical and three complication variables. Postoperative 30-day outcomes include 20 complications as well as 12 laboratory and 10 discharge variables. Real-time benchmarking allows outcomes to be compared with those of other ACS-NSQIP hospitals using online reports. Semi-annual reports provide risk-adjusted comparisons of all ACS-NSQIP hospitals for multiple morbidity outcomes, as well as for mortality outcomes. In 2008 a Participant Use File (PUF) containing all cases entered during 2005–2007 became available (Fig. 1B). In 2007 data on more than 200 000 operations were entered into the PUF.

Participant Use File

To assure the high quality of the data, ACS-NSQIP conducts inter-rater reliability audits of the SCNRs, requires six web-based training modules, and provides an online decision support system. The overall disagreement rate for all 136 variables is only 2.5%. In addition to the case inclusion and exclusion criteria described above, hospital inclusion and exclusion criteria are imposed for the PUF. Only cases included in the morbidity and mortality observed/expected (O/E) ratio analyses are included in the PUF. A site may be excluded from the O/E calculation and the PUF if: (i) the 30-day follow-up rate is < 80%; (ii) the inter-rater reliability audit score is >5%, or (iii) fewer than 200 cases have been submitted in the calendar year. Nevertheless, the PUF has a number of deliberate limitations that aim to ensure patient privacy, as well as limitations imposed by resource constraints. These limitations pertain to: (i) the generic nature of most outcome measures; (ii) the exclusion of patients under 17 years of age and the lumping together of those aged over 90 years; (iii) the fact that follow-up is limited to 30 days; (iv) the removal of absolute dates; (v) the de-identification of participating sites; (vi) the absence of records of many preventative measures; (vii) the relatively small number of participating hospitals; (viii) incomplete sets of some preoperative laboratory data, and (ix) limited information on pathological diagnosis and cancer therapies.

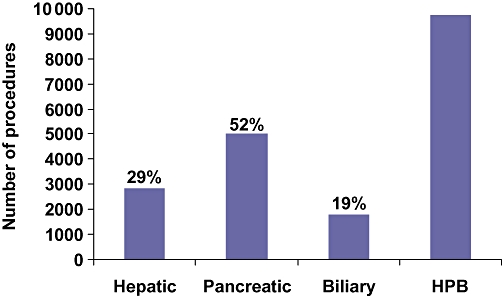

Morbidity and mortality indices

Morbidity and mortality rates are calculated by sorting PUF data according to the principal operative procedure, which is defined as the most complex of all the procedures performed by the operating team. For example, if a hepatectomy and a cholangiojejunostomy are performed for a perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, the procedure is included with major hepatectomies and not with complex biliary operations. Procedures are listed according to current procedure terminology (CPT) codes, which are employed nationally in the USA for billing purposes. Outcomes for 49 HPB operations carried out between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2007 were assessed. The procedures included six hepatic, 16 pancreatic and 23 complex biliary operations. Four laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy operations were also studied. Data were available on 9723 HPB operations and 44 189 cholecystectomies (Table 1). Of the HPB operations, 29% were hepatic, 52% were pancreatic and 19% were complex biliary procedures (Fig. 2). For each patient or procedure recorded in the PUF, 239 variables are listed, including the probability of morbidity and the probability of mortality. The probabilities of morbidity and mortality are based on a logistic regression analysis which uses the patient's preoperative characteristics as the independent or predictive variables. For example, patients with lower serum albumin, poorer functional states and more co-morbidities, who are undergoing larger operations, will have a higher expected morbidity and mortality than more functional patients undergoing smaller operations. These probability analyses are performed independently on data from each calendar year. The observed (O) morbidity or mortality was divided by the expected (E, probability) morbidity or mortality to obtain the morbidity and mortality observed/expected (O/E) indices.

Table 1.

American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) Participant Use File data for 2005–2007 for hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) and cholecystectomy cases

| Hepatic | Pancreatic | Biliary* | HPB | Cholecystectomy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures | 6 | 16 | 23 | 45 | 4 |

| Number | 2847 | 5074 | 1802 | 9723 | 44 189 |

Complex procedures

Figure 2.

Number and percentage of hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) procedures in the ACS-NSQIP Participant Use File

Results

Hepatic morbidity and mortality

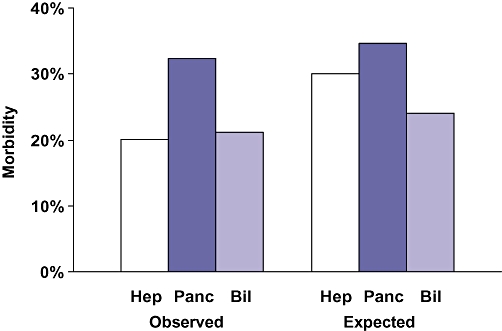

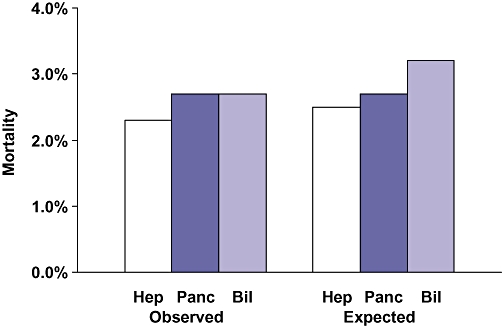

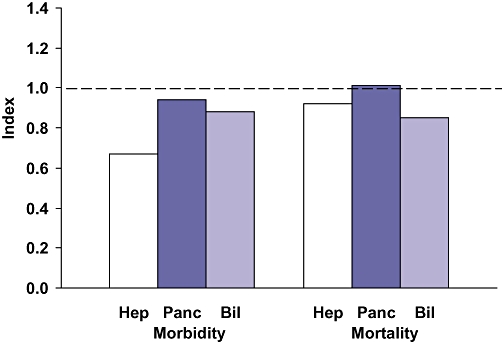

Data for six hepatic surgery procedures are presented in Table 2. Patients undergoing hepatectomy were more likely to have metastatic disease (42%) and recent chemotherapy (7%) than those undergoing pancreatectomy or complex biliary operations. Minor (partial lobe) hepatectomies accounted for 55% of the 2843 operations. Morbidity (35.7%) and mortality (5.2%) were highest for extensive hepatectomies (n= 230). Right hepatectomies were associated with higher morbidity (27.9% vs. 21.5%) and mortality (3.7% vs. 0.9%) than left hepatectomies. Laparoscopic hepatectomy was performed in 350 patients (13%) with low morbidity (4.6%) and mortality (0.8%). Interestingly, the expectedmorbidity for laparoscopic hepatectomy was less than 20% of that for open minor hepatectomies and less than 12% of the morbidity for major hepatectomies. Similarly, the expected mortality for laparoscopic hepatectomy was only a fraction of that for open hepatectomy, which suggests that patients who underwent laparoscopic procedures were much healthier. For all hepatic surgery, the observed morbidity (Fig. 3) and mortality (Fig. 4) were less than expected, yielding a morbidity index of 0.67 and a mortality index of 0.92.

Table 2.

Hepatic surgery morbidity, mortality and observed/expected indices

| CPT code | Principal procedure | n | Observed morbidity, % | Expected morbidity, % | Morbidity index | Observed mortality, % | Expected mortality, % | Mortality index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47120 | Hepatectomy, partial lobe | 1357 | 18.1 | 26.4 | 0.69 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.82 |

| 47122 | Hepatectomy, extensive | 230 | 35.7 | 49.8 | 0.72 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 1.41 |

| 47125 | Hepatectomy, left | 233 | 21.5 | 42.0 | 0.51 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 0.29 |

| 47130 | Hepatectomy, right | 512 | 27.9 | 46.2 | 0.60 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.09 |

| 47379 | Hepatectomy, laparoscopic | 350 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 0.81 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.38 |

| 47380 | Ablation, radiofrequency | 165 | 21.8 | 18.8 | 1.16 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.89 |

| Total | 2847 | 20.1 | 30.1 | 0.67 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.92 |

CPT code, current procedure terminology

Figure 3.

Observed and expected hepato-pancreato-biliary morbidity. Hep, hepatic procedure; Panc, pancreatic procedure; Bil, biliary procedure

Figure 4.

Observed and expected hepato-pancreato-biliary mortality. Hep, hepatic procedure; Panc, pancreatic procedure; Bil, biliary procedure

Pancreatic morbidity and mortality

Data for eight pancreatectomies and eight other pancreatic surgery procedures are presented in Table 3. Of 1391 distal pancreatectomies, 89% were performed without a pancreatojejunostomy or a subtotal resection. For distal pancreatectomy, morbidity (26.8%) and mortality (1.9%) were higher than expected (O/E indices of 1.58 and 1.36, respectively). Of the 2889 proximal pancreatectomies, 58% were performed with a gastrectomy (Whipple) and 42% with pylorus preservation (pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy [PPPD]). All but 117 of these operations (4%) were performed with a pancreatojejunostomy anastomosis. Morbidity and mortality indices were similar for Whipple and PPD procedures, but mortality was higher for the Whipple operations (3.6% vs. 3.0%). Of the 5074 pancreatic operations, 4373 (86%) were pancreatectomies, and all other operations were uncommon. The observed morbidity for pancreatectomy (32.4%) was higher than for the other pancreatic operations (22.5%). However, the morbidity index for pancreatectomy was lower (0.94 vs. 1.40). Both the observed and expected morbidity for pancreatic surgery were higher than for hepatic or complex biliary surgery (Fig. 3). The observed mortality for pancreatectomy (2.7%) was higher than for other pancreatic surgery (0.9%), as was the mortality index (1.01 vs. 0.57) (Table 3). The observed and expected mortality for pancreatectomy were slightly higher than for hepatectomy (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Pancreatic surgery morbidity, mortality and observed/expected indices

| CPT code | Principal procedure | n | Observed morbidity, % | Expected morbidity, % | Morbidity index | Observed mortality, % | Expected mortality, % | Mortality index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatectomy | ||||||||

| 48140 | Pancreatectomy, distal w/o PJ | 1241 | 26.8 | 17.0 | 1.58 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.36 |

| 48145 | Pancreatectomy, distal w PJ | 103 | 35.0 | 18.0 | 1.94 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.90 |

| 48146 | Pancreatectomy, distal subtotal | 47 | 31.9 | 25.2 | 1.27 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 1.79 |

| 48150 | Pancreatectomy, proximal Whipple w PJ | 1588 | 37.0 | 44.2 | 0.84 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 0.94 |

| 48152 | Pancreatectomy, proximal Whipple w/o PJ | 70 | 48.6 | 42.0 | 1.16 | 10.0 | 4.7 | 2.13 |

| 48153 | Pancreatectomy, proximal PPPD w PJ | 1184 | 30.8 | 42.2 | 0.73 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 0.72 |

| 48154 | Pancreatectomy, proximal PPPD w/o PJ | 47 | 36.2 | 40.9 | 0.89 | 8.5 | 5.3 | 1.60 |

| 48155 | Pancreatectomy, total | 93 | 37.6 | 25.0 | 1.50 | 5.4 | 3.4 | 1.59 |

| Total | 4373 | 32.4 | 34.6 | 0.94 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.01 | |

| Other pancreatic | ||||||||

| 48120 | Excision of lesion | 113 | 18.6 | 11.8 | 1.58 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.00 |

| 48148 | Excision of ampulla | 20 | 30.0 | 15.5 | 1.94 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.00 |

| 48180 | Pancreatojejunostomy, side-to-side* | 63 | 23.8 | 18.3 | 1.30 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 2.00 |

| 48510 | Pseudocyst, external drainage | 52 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 1.04 | 1.9 | 7.1 | 0.27 |

| 48520 | Pseudocyst, cystenterostomy | 131 | 26.7 | 21.4 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 0.68 |

| 48540 | Pseudocyst, Roux-Y | 96 | 16.7 | 16.3 | 1.02 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.00 |

| 48548 | Pancreatojejunostomy, side-to-side | 70 | 22.9 | 19.4 | 1.18 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.00 |

| 48999 | Unlisted | 156 | 20.5 | 7.5 | 2.70 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.86 |

| Total | 701 | 22.5 | 16.1 | 1.40 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.57 | |

Code deleted in 2007

CPT code, current procedure terminology; PJ, pancreatojejunostomy; PPPD, pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy

Complex biliary morbidity and mortality

Data for nine complex biliary procedures are presented in Table 4. These 1537 operations accounted for 85% of the complex biliary procedures. These patients were more likely to have significant weight loss (20%), diabetes (13%) and ascites (5%) than patients undergoing hepatectomy or pancreatectomy. Numbers of these nine operations varied from 422 to 33, whereas the other 14 complex biliary procedures accounted for 265 operations, a mean of 18.9 cases per procedure. Hepatico- or cholangiojejunostomy accounted for 766 of the complex biliary operations (43%). The observed morbidity was 32% for these operations, which was modestly less than expected. The mortality for these biliary-enteric anastomoses was 2.7%, which, again, was moderately less than expected. Only 435 open common duct explorations (CDEs) were carried out, most (n= 299) of which were performed without a drainage procedure. Interestingly, 273 laparoscopic CDEs were performed. Therefore, 37% of the CDEs were accomplished laparoscopically. The morbidity for open CDE was 22%, compared with only 3.3% for laparoscopic CDE. However, the expected morbidity for open CDE was 23%, compared with 9% for laparoscopic CDE, which again suggests that patients who underwent the operation laparoscopically were healthier. The overall morbidity and mortality indices for these 14 complex biliary operations (Table 4) were 0.88 and 0.85, respectively. The observed morbidity for complex biliary operations was similar to that for hepatectomy, but lower than that for pancreatectomy (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the observed mortality for the complex biliary operations (2.7%) was equal to that for pancreatectomy and exceeded that for hepatectomy (2.3%) (Fig. 4). Moreover, the expected mortality (3.2%) was highest for complex biliary surgery (Fig. 4). Thus, the morbidity O/E index was lowest for hepatectomy, whereas the mortality O/E index was lowest for complex biliary surgery (Fig. 5).

Table 4.

Complex biliary surgery morbidity, mortality and observed/expected indices

| CPT code | Principal procedure | n | Observed morbidity, % | Expected morbidity, % | Morbidity index | Observed mortality, % | Expected mortality, % | Mortality index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47420 | Choledochotomy, CDE, sphincteroplasty | 61 | 27.9 | 23.7 | 1.18 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 1.22 |

| 47460 | Transduodenal sphincteroplasty | 63 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 1.07 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.00 |

| 47564 | Lap chole w CDE | 273 | 3.3 | 9.1 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.36 |

| 47610 | Open chole w CDE | 299 | 22.1 | 22.9 | 0.97 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 1.14 |

| 47612 | Open chole w CDE w CD ent | 75 | 14.7 | 20.5 | 0.72 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.00 |

| 47760 | Hepaticojejunostomy | 125 | 20.0 | 27.2 | 0.74 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.59 |

| 47765 | Cholangiojejunostomy | 33 | 33.3 | 39.1 | 0.85 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 1.03 |

| 47780 | Roux-Y hepaticojejunostomy | 422 | 29.9 | 31.2 | 0.96 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 0.76 |

| 47785 | Roux-Y cholangiojejunostomy | 186 | 28.5 | 38.3 | 0.74 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.94 |

| Total | 1537* | 21.2 | 24.0 | 0.88 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 0.85 |

14 other procedure codes accounted for 265 operations (mean = 18.9 procedures per operation type)

CPT code, current procedure terminology; CDE, common duct exploration; Lap chole, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; CD ent, choledochoenteric anastomosis

Figure 5.

Hepato-pancreato-biliary morbidity and mortality observed/expected indices. Hep, hepatic procedure; Panc, pancreatic procedure; Bil, biliary procedure

Cholecystectomy morbidity and mortality

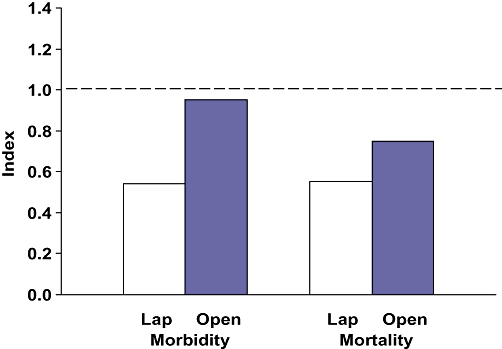

Data for four cholecystectomy procedures are presented in Table 5. The 44 189 cholecystectomies in the PUF database outnumbered the HPB operations by more than 4.5 to one. Of the 44 189 cholecystectomies, 40 188 (92%) were performed laparoscopically. An operative cholangiogram was accomplished in only 27% of the laparoscopic and 19% of the open cholecystectomies. The observed morbidity for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (6.0%) was much lower than for open cholecystectomy (19.2%). Similarly, the observed mortality for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (0.3%) was much lower than for open cholecystectomy (2.5%). However, the expected morbidity of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was approximately one-third of that for the open procedure. Similarly, the expected mortality of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was less than 20% of that for open cholecystectomy. Similar to the data for laparoscopic hepatectomy and laparoscopic CDE, these cholecystectomy outcomes suggest that patients who underwent this operation were healthier than those who required an open operation. Thus, the morbidity and mortality O/E indices for laparoscopic cholecystectomy are lower than those for open cholecystectomy, but all of these ratios are < 1.0 (Fig. 6).

Table 5.

Cholecystectomy morbidity, mortality and observed/expected indices

| CPT code | Principal procedure | n | Observed morbidity, % | Expected morbidity, % | Morbidity index | Observed mortality, % | Expected mortality, % | Mortality index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47562 | Laparoscopic chole | 29 245 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 0.56 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.60 |

| 47563 | Lap chole w cholangio | 10 943 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 0.50 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.43 |

| 47600 | Open cholecystectomy | 3 237 | 18.6 | 19.4 | 0.96 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 0.69 |

| 47605 | Open chole w cholangio | 764 | 16.5 | 18.3 | 0.90 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 0.87 |

| Total | 44 189 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 0.64 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.63 |

CPT code, current procedure terminology; chole, cholecystectomy; Lap, laparoscopic; cholangio, cholangiogram

Figure 6.

Cholecystectomy morbidity and mortality observed/expected indices. Lap, laparoscopic

Discussion

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program has grown rapidly since its inception in 2004. During 2005–2007, data on nearly 10 000 major HPB operations and more than 44 000 cholecystectomies were made available in the PUF. Among the major HPB operations, 29% were hepatic, 52% pancreatic and 19% complex biliary procedures. Morbidity was highest for pancreatectomy (32.4%) compared with complex biliary operations (21.2%) or hepatectomy (20.1%). Mortality was higher for pancreatectomy (2.7%) and complex biliary surgery (2.7%) than for hepatectomy (2.3%). Morbidity and mortality were much lower for laparoscopic hepatectomy, CDE and cholecystectomy than for comparable open operations. However, the expected morbidity and mortality in patients who underwent these operations laparoscopically were also much lower, indicating a healthier patient population. The O/E morbidity and mortality indices for both major HPB operations and cholecystectomy were all < 1.0. This analysis suggests that ACS-NSQIP hospitals are performing HPB surgery safely.

The success of ACS-NSQIP can be attributed to several core strengths.8 These attributes include: (i) data abstraction by trained nurses; (ii) rigorously defined variables; (iii) a comprehensive set of clinical and laboratory risk factors; (iv) well-validated risk adjustment models, and (v) external auditing of data for completeness and accuracy. As a result, participating hospitals receive very robust risk-adjusted estimates of their surgical morbidity and mortality. By contrast, hospital enrolment has been limited by several problems. These issues include: (i) high costs; (ii) the relatively ‘generic’ nature of most performance measures; (iii) the lack of procedure-specific outcomes; (iv) the paucity of processes of care measures, and (v) the absence of surgeon-specific data. In response to these concerns, a new leadership and organizational structure was created for ACS-NSQIP in 2007.8 The Measurement and Evaluation Committee was charged with developing a blueprint for a new and improved ACS-NSQIP. A key recommendation has been to develop a specialty-specific approach which evolves away from the random sampling of all procedures towards 100% sampling of selected procedures.

A new version of ACS-NSQIP being developed in 2009 will include five ‘core’ and seven ‘optional’ procedures (Table 6). Two of the five core procedures, cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis and pancreatectomy, are HPB operations. Similarly, two of the seven optional procedures, cholecystectomy (all) and hepatectomy, are HPB operations. These procedures were chosen because of their contributions to the overall number of major adverse events. Thus, only the relatively uncommon other HPB operations (Table 3) and complex biliary procedures (Table 4) will not be included in the next version of ACS-NSQIP. In addition, data on 12–15 patient- and procedure-specific variables, such as cirrhosis, preoperative biliary drainage, vascular resection, liver failure and pancreatic fistula, will be gathered with the next version of ACS-NSQIP. Therefore, extension to a full HPB-NSQIP as a specialty-specific module should be straightforward. Efforts are currently underway to reduce the number of ‘generic’ patient characteristics and risk factors as previous studies based on NSQIP data suggest that risk modules require fewer than 10 variables.2,3,8,9 A reduction of the number of core covariates to focus on those that will discriminate hospital- or surgeon-level variations in outcomes will reduce the burden and cost of data collection. The adoption of a minimum set of core covariates will also allow for the inclusion of important risk factors for specific procedures, as well as procedure-specific outcomes.

Table 6.

New American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program core and optional general surgery procedures

| Core procedures | Optional procedures |

|---|---|

| Cholecystectomy (acute cholecystitis) | Cholecystectomy (all) |

| Colectomy | Proctectomy (rectal cancer) |

| Gastric bypass | Oesophagectomy |

| Pancreatectomy | Hepatectomy |

| Ventral herniorrhaphy | Appendectomy |

| Small bowel obstruction surgery | |

| Thyroidectomy |

The types of data that might be included as an HPB-NSQIP option is developed are outlined in Table 7. A basic demographic variable might be the definition of an ‘HPB surgeon’. Key preoperative risk factors to be added in HPB-NSQIP would include: (i) hepatobiliary variables such as cirrhosis and biliary obstruction; (ii) diagnostic tests; (iii) local conditions, such as cholecystitis or pancreatitis; (iv) antecedent related procedures, such as endoscopic sphincterotomy; (v) related prior surgery, such as cholecystectomy, and (vi) neoadjuvant therapies. In addition to HPB-specific procedure codes, operative information might include: (i) data not currently provided by these codes, such as ischaemic preconditioning, vascular resection and the use of drains, and (ii) organ specifics such as fibrosis, steatosis and inflammation. Moreover, outcome information to be added in HPB-NSQIP would include additional: (i) procedure-specific morbidities; (ii) postoperative interventions; (iii) pathological data; (iv) adjuvant chemo-, radio- or immune therapy, and (v) for research purposes, patient survival. Finally, the new ACS-NSQIP and HPB-NSQIP would include process of care measures such as those presently required by the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP).

Table 7.

Potential Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (HPB-NSQIP) specific data

| Preoperative risk factors |

|---|

| Hepatobiliary – cirrhosis, biliary obstruction |

| Methods of diagnosis |

| Concurrent local conditions |

| Antecedent related procedures |

| Related prior surgery |

| Neoadjuvant therapy |

| Operative information |

| Procedure-specific |

| Hepatic – number of segments, Pringle, drains |

| Pancreatic – vascular resection, reconstruction, drains |

| Biliary – cholangiography, conversion, drains |

| Organ-specific |

| Hepatic – fibrosis, fat |

| Pancreatic – texture, duct |

| Biliary – cholecystitis, cholangitis |

| Outcome information |

| Procedure-specific |

| Hepatic – liver failure, biloma |

| Pancreatic – fistula, delayed gastric emptying |

| Biliary – bile duct injury, cholangitis |

| Postoperative interventions |

| Pathology (ICD-9-CM) |

| Malignant – type, location, resection status |

| Tumour–nodes–metastases (TNM) |

| Benign – type, size, location |

| Adjuvant therapy |

| Survival |

Several prior studies have reported single-institution outcomes of relatively large numbers of patients undergoing hepatectomy.10–13 Similarly, the NSQIP Patient Safety in Surgery (PSS) Study reported the outcomes of 237 liver resections at VA hospitals compared with 783 similar operations at university hospitals.14–16 Using similar definitions, the current analysis had slightly lower morbidity (20.1% vs. 22.6%) and mortality (2.3% vs. 2.6%) rates than those calculated for university hospital patients in the PSS Study. In addition, the number of patients in the current analysis (2847) exceeds those of the prior reports.10–16 The importance of volume in outcomes for pancreatectomy has been well documented.17–21 VA-NSQIP,21 large series from single institutions,22 and comparative VA and university data on pancreatectomy in the PSS Study23 have been reported. The current analysis involved 4373 patients compared with 1069 in the PSS Study, with similar overall morbidity (32.4% vs. 33.8%) and mortality (2.7% vs. 2.5%) to the 692 university patients. Analyses of hepatico- or cholangiojejunostomy have generally focused on benign24,25 or malignant26,27 biliary strictures. Thus, the current data on complex biliary surgery are relatively unique. In the PSS Study, data on laparoscopic cholecystectomy were available on 7238 men7 and 4460 women.28 However, the current analysis involves nearly four times as many patients and provides more robust outcome data.

In the new ACS-NSQIP and the future HPB-NSQIP, surgeon-specific performance data for both process and outcome measures would be more feasible. Although small sample size would be an issue, some data, such as those pertaining to compliance with antibiotic guidelines, could be aggregated across multiple HPB procedures. These types of data would be applicable to the American Board of Surgery Maintenance of Certification programme and would also meet surgeon-credentialing criteria for the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The adoption of hierarchical modelling techniques rather than logistic regression would provide better data for low-volume programmes and would more reliably identify hospital outliers.8 Thus, the creation of an HPB-NSQIP as a further modification of ACS-NSQIP has the potential to improve quality, provide risk-adjusted registries with HPB-specific data and facilitate multi-institutional clinical trials.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson WG, Barbour G, Lowry P, Irvin G. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson WG, Hur K, Gibbs JO, Barbour G. Risk adjustment of the postoperative mortality rate for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:315–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley J, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Hur K, Gibbs JO, Barbour G. Risk adjustment of the postoperative morbidity rate for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:328–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson WG, Hur K, Hur K, Demakis J, Aust JB. The Department of Veterans Affairs' NSQIP. The first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled programme for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. Ann Surg. 1998;228:491–507. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink AS, Campbell DA, Mentzer RM, Jr, Henderson WG, Daley J, Bannister J. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-VA hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Ann Surg. 2002;236:344–354. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J, Jonasson O, Jones RS, Campbell DA., Jr The Patient Safety in Surgery Study: background, study design, and patient populations. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1089–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Mosca C, Fink AS, Hutler MM, Neumayer LA. Comparison of risk-adjusted 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals and selected university medical centres: general surgical operations in men. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkmeyer JD, Shahian DM, Dimick JB, Finlayson SR, Flum DR, Lo CY, et al. Blueprint for a new American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schifftner TL, Grunwald GK, Henderson WG, Main D, Churi SF. Relationship of processes and structures of care in general surgery to postoperative outcomes: a hierarchical analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, Massault P, Souvanet A, Farges A. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:38–46. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1801 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000029003.66466.B3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, et al. Improving perioperative outcome expands the role of hepatectomy in management of benign and malignant hepatobiliary diseases: analysis of 1222 consecutive patients from a prospective database. Ann Surg. 2004;240:698–708. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141195.66155.0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimick JB, Wainess RM, Cowan JA, Upchurch GR, Jr, Knol JA, Colletti LM. National trends in the use and outcomes of hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancaster RT, Tanabe KK, Schifftner TL, Washaw AL, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, et al. Liver resection in Veterans Affairs and selected university medical centres: results of the Patient Safety Surgery Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1242–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virani S, Michaelson JS, Hutter MM, Lancaster RT, Warshaw AL, Henderson WG, et al. Morbidity and mortality after liver resection: results of the Patient Safety in Surgery Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gedaly R, McHugh PP, Johnston TD, Jeon H, Ranjan D, Davenpor DL, et al. Obesity, diabetes and smoking are important determinants of resource utilization in liver resection: a multicentre analysis of 1029 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;243:414–419. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a032d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg. 1995;221:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Gordon TA, Bass EB, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, et al. Importance of hospital volume in the overall management of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;228:429–438. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birkmayer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billingsley KG, Hur R, Henderson WG, Daley J, Khuri SF, Bell RH, Jr., et al. Outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary cancer: an analysis from the Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:484–491. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreatico-duodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10–15. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Jackson HH, Neumayer L, Schifftner TL, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, et al. Pancreatic resection in Veterans Affairs and selected university medical centres: results of the Patient Safety in Surgery Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1252–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Talamini MA, et al. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786–795. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161029.27410.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlik TM, Olbrecht VA, Pitt HA, Gleisner AL, Choti MA, Schulick RD, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: the role of extrahepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Hruban RH, Abrams R, Yeo CJ, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: a spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumours. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–475. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, Erickson BA, Ritch PS, Quebbeman EJ, et al. Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies. Surgery. 2002;132:555–564. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink AS, Hutter MM, Campbell DC, Jr, Henderson WG, Mosca C, Khuri SF. Comparison of risk-adjusted 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals and selected university medical centres: general surgical operations in women. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1127–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]