Abstract

Background:

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by the sudden onset of coagulopathy and encephalopathy. The outcome is unpredictable and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. We reviewed our experience to identify the aetiology and study the outcome of acute liver failure.

Methods:

A total of 1237 patients who presented with acute liver failure between January 1992 and May 2008 were included in this retrospective study. Liver transplantation was undertaken based on the King's College Hospital criteria. Data were obtained from the units prospectively collected database. The following parameters were analysed: patient demographics, aetiology, operative intervention, overall outcome, 30-day mortality and regrafts.

Results:

There were 558 men and 679 women with a mean age of 37 years (range: 8–78 years). The most common aetiology was drug-induced liver failure (68.1%), of which 90% was as a result of a paracetamol overdose. Other causes include seronegative hepatitis (15%), hepatitis B (2.6%), hepatitis A (1.1%), acute Budd–Chiari syndrome (1.5%), acute Wilson's disease (0.6%), subacute necrosis(3.2%) and miscellaneous (7.8%). Three hundred and twenty-seven patients (26.4%) were listed for liver transplantation, of which 263 patients successfully had the procedure (80.4%). The current overall survival after transplantation was 70% with a median follow-up of 57 months. After transplantation for ALF, the 1-year, 5-year and 10-year survival were 76.7%, 66% and 47.6%, respectively. The 30-day mortality was 13.7%. Out of the 974 patients who were not transplanted, 693 patients are currently alive. Among the 281 patients who died without transplantation, 260 died within 30 days of admission (26.7%). Regrafting was performed in 31 patients (11.8%), the most common indication being hepatic artery thrombosis (11 patients).

Conclusion:

Paracetamol overdose was the most common cause of acute liver failure. Liver transplantation, when performed for acute liver failure, has good long-term survival.

Keywords: acute liver failure, transplantation

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by the sudden onset of coagulopathy and encephalopathy in an otherwise healthy person with no underlying liver disease. The aetiology of ALF varies significantly worldwide. Paracetamol overdose is the predominant cause of ALF in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US).1,2 Viral aetiology is the most common cause in the developing countries.3

ALF is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The outcome is highly unpredictable. The chance of recovery depends on the underlying aetiology, age of the patient, duration of time over which the disease develops, the extent of liver damage and early institution of supportive care.3 Outcome without liver transplantation is better overall in patients with pregnancy-related syndromes, paracetamol overdose and hepatitis A, and poorer in older patients and in very young children.4

In recent years, liver transplantation has emerged as a viable treatment option in patients with ALF. It is mainly employed as a salvage therapy for individuals who are unable to recover from ALF.

Although several studies are available in the literature regarding the outcome of liver transplantation in ALF in the UK, only limited data are available until date on the outcome of ALF itself.5–8 Being one of the largest transplant centres in the UK, we reviewed our experience to identify the aetiology and study the outcome of patients with ALF.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective descriptive study performed over a period of 16 years, from January 1992 to May 2008. All patients who were referred and admitted at the University Hospital of Birmingham (UHB), with the diagnosis of ALF during the study period were included. ALF was defined according to the criteria of O'Grady et al., as the onset of hepatic encephalopathy occurring within 12 weeks of onset of jaundice.9 After admission to the liver intensive care unit, the patients were managed with aggressive supportive therapy and closely monitored under the joint care of liver surgeons, hepatologists and intensivists. All patients with drug-induced liver failure received N-acetyl cysteine whereas patients with others causes of ALF did not. The criteria for listing for liver transplantation were standardized and were based on the previously described King's College Hospital criteria.10

Data were obtained from the prospectively maintained liver database at the UHB. The parameters analysed were patient demographics, aetiology of ALF, operative intervention, overall outcome after transplantation, short-term outcome in non-transplanted patients, post-transplant complications, re-grafts and mortality.

Aetiological diagnosis was based on the detailed clinical information and laboratory data. Viral aetiology was confirmed based on the screening for serological markers of Hepatitis A, B, C and E viral infections, including IgM antibodies against HAV and HBV and for auto-antibodies. These include antinuclear antibodies, antiliver-kidney microsome antibodies and anti-smooth muscle antibodies. Drugs were implicated as aetiological agent based on the detailed medical history at admission. Diagnosis of Wilson's disease was based on the serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels, the presence of the Kayser–Fleisher ring and family history. Diagnosis of Budd–Chiari syndrome was confirmed on abdominal imaging. Seronegative hepatitis is a presumed non-A,B,C,E hepatitis with a hepatitic picture. Extensive medical history was obtained from these patients to exclude intake of any dietary or herbal supplements or medications that could cause ALF. However, they did not have routine blood tests as a standard protocol, to investigate for commonly implicated dietary supplements (muscle building or weight loss medications or supplements that include extracts of green tea). Subacute necrosis refers to the time course of hepatitis, the jaundice to encephalopathy time being greater than 8 weeks and less than 3 months.

Results are expressed as median and ranges. Data analysis was done with SPSS for Windows® software (version 13; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The overall survival was evaluated by Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

During the study period, a total of 1237 patients were admitted with the clinical diagnosis of ALF. There were 558 men and 679 women. The median age at presentation was 37 years (range: 8–78 years).

Aetiology of ALF

Drug-induced liver failure was the predominant causative factor, accounting for 68.1% of patients admitted with ALF. The most common drug implicated was paracetamol (90%). The other drugs responsible for ALF are listed in Table 1. Twenty-four patients, listed as ‘unknown drugs’, had a combination of multiple drugs with alcohol as the only aetiological agent for ALF.

Table 1.

List of drugs implicated in acute liver failure (ALF)

| Drugs | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 759 |

| Isoniazid | 18 |

| Ecstasy | 8 |

| Chinese herbal medicine | 5 |

| Halothane | 2 |

| Cocaine/alcohol | 3 |

| Voltarol | 2 |

| Augmentin | 2 |

| Carbamazepine | 2 |

| Rifampicin | 1 |

| Omeprazole | 1 |

| Clarithromycin | 1 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 1 |

| Flucloxacillin | 1 |

| Fluoxetine | 1 |

| Dothiepen | 1 |

| Trimethoprim | 1 |

| Azathioprine | 1 |

| Phenytoin | 1 |

| Glivec | 1 |

| Sulphasalazine | 2 |

| Amiadarone | 1 |

| Chloroquine | 1 |

| Norethisterone | 1 |

| Orlestat | 1 |

| Antabuse | 1 |

| Unknown | 24 |

Fulminant seronegative hepatitis was deemed responsible in 15% of ALF. Hepatitis A and B viral infections accounted for 1.1% and 2.6%, respectively. The presumptive diagnoses of subacute necrosis, acute Budd–Chiari syndrome and acute Wilson's disease were found to be responsible for ALF in 3.2%, 1.5% and 0.6%, respectively. Miscellaneous causes included pregnancy-associated ALF, acute fatty liver, Epstein-Barr and hepatitis E viral infections. This group accounted for ALF in 7.8% of patients.

Listing and transplantation

Three hundred and twenty-seven patients were listed for emergency liver transplantation, of which 263 patients successfully received a liver graft (80.4% of listed patients and 21.3% of all patients with ALF). The number of patients listed for emergency orthotopic liver transplantation varied widely between different aetiological agents. Patients with acute Wilson's disease or fulminant seronegative hepatitis are likely to be listed for transplantation, whereas hepatitis A viral infection and drug-induced liver failure are less likely to be listed (Table 2). Transplantation was performed in only 10.4% of the drug-induced group, 14.3% of the hepatitis A viral infection group, 16.7% of the acute Budd–Chiari group, 18.8% of the hepatitis B viral infection group, as compared with 100% of acute Wilson's group, 68.8% of the fulminant seronegative hepatitis group and 61.5% of the subacute necrosis group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of patients listed and transplanted for acute liver failure (ALF) in different aetiological subgroups

| Aetiology | ALF (n) | Listed –n (%) | Transplantedn (% of listed) | Transplantedn (% of ALF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug induced | 843 | 118 (14) | 88 (74.6) | 88 (10.4) |

| Seronegative hepatitis | 186 | 149 (80.1) | 128 (85.9) | 128 (68.8) |

| Hepatitis B | 32 | 10 (31.3) | 6 (60) | 6 (18.8) |

| Hepatitis A | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 2 (100) | 2 (14.3) |

| Acute Budd–Chiari | 18 | 5 (27.8) | 3 (60) | 3 (16.7) |

| Acute Wilson's disease | 8 | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Subacute necrosis | 39 | 25 (64.1) | 24 (96) | 24 (61.5) |

| Miscellaneous | 97 | 10 (10.3) | 4 (40) | 4 (4.1) |

| Total | 1237 | 327 (26.4) | 263 (80.4) | 263 (21.3) |

When the number of patients transplanted was analysed against those listed, it was found that 85.9% of the listed seronegative hepatitis patients were transplanted as opposed to nearly three-fourth (74.6%) of the listed drug-induced ALF patients (Table 2). These two aetiologies were compared, both being the bigger subgroups. The difference was found to be statistically significant (P= 0.019).

Outcome of transplanted patients

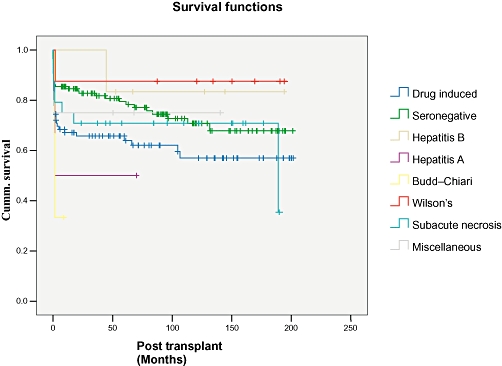

One hundred and eighty-four patients out of the 263, who received liver graft, are still alive. The overall survival was 70% with a median survival of 57 months (range: 0–197 months). After transplantation for ALF, the 1-year, 5-year and 10-year survival rates were 76.7%, 66% and 47.6%, respectively (Table 3). When survival was analysed individually for different aetiological subgroups, it was found that acute Wilson's disease and hepatitis B viral infection had favourable 1-, 5- and 10-year survival rates and acute Budd–Chiari syndrome had the lowest survival rates (Table 3). Figure 1 compares the cumulative survival after transplantation in different aetiological groups. When survival was compared between drug-induced liver failure and seronegative hepatitis, both being bigger subgroups, it was found that seronegative hepatitis had significantly better 1- and 5-year survival rates (P= 0.002 and P= 0.051 respectively).

Table 3.

One-, 5- and 10-year survival of transplanted patients according to aetiological subgroups

| Aetiology | Transplanted (n) | 1-year survival (%) | 5-year survival (%) | 10-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug induced | 88 | 65.9 | 57.4 | 42.1 |

| Seronegative hepatitis | 128 | 84.3 | 72.2 | 47.5 |

| Hepatitis B | 6 | 100 | 80 | 75 |

| Hepatitis A | 2 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Acute Budd–Chiari | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute Wilson's disease | 8 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 85.7 |

| Subacute necrosis | 24 | 75 | 63.2 | 53.3 |

| Miscellaneous | 4 | 75 | 66.7 | 50 |

| Total | 263 | 76.7 | 66 | 47.6 |

Figure 1.

Cumulative survival curves comparing different aetiological groups

Post-transplant complications included infection (herpes viral infection – 44 patients, CMV infection – 28 patients, shingles – 3 patients and aspergillosis – 5 patients), biliary complications (bile leak – 10 patients, biliary stricture – 24 patients), malignancy (Basal cell cancer – 6 patients, lymphoma – 6 patients), graft complications (primary non-function – 4 patients, chronic rejection – 13 patients, hepatic artery thrombosis – 13 patients) and inferior venacaval (IVC) pathology (IVC thrombosis – 1 patient, IVC stenosis – 1 patient).

After transplantation, 79 patients died, of whom 36 died within 30 days of surgery (30-day mortality: 13.7%). Drug-induced liver failure had the highest 30-day mortality of 21.6%. The 43 patients who died after 30 days of transplantation, had a median survival of 10 months (range: 1–189 months). The causes of death in this group of patients were systemic sepsis (bacterial – 14 patients, fungal – 7 patients, viral – 3 patients), graft-related complications (chronic rejection – 5 patients, primary non-function – 1 patient, hepatic artery thrombosis – 1 patient, lymphoproliferative disorder – 2 patients, recurrent disease – 2 patients and metastatic tumour – 2 patients) and others (suicide – 2 patients and renal failure, myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident – 1 patient each). Out of the two patients who committed suicide, one died of a paracetamol overdose within 2 months of transplantation and the other died of a non-medicated method 5 years after transplantation.

Re-transplantation was performed in 31 patients (11.8%). The median interval between first transplant and re-graft was 5 months (range: 1 day to 182 months). The indications for re-transplantation were hepatic artery thrombosis (11 patients), chronic rejection (10 patients), primary non-function (4 patients), haemorrhagic necrosis (2 patients), acute rejection (1 patient), recurrent disease (1 patient) and secondary biliary cirrhosis (2 patients). Three of the 11 hepatic artery thrombosis occurred within 2 weeks of primary transplantation and hence they are likely to be technical failures. Another three patients had the thrombosis between 2 weeks and 3 months, and the remaining patients had it after 3 months of transplantation. The aetiology of hepatic artery thrombosis was not clear in these patients.

Outcome of not transplanted patients

A total of 974 patients did not have transplantation. This includes the 64 patients who were listed for transplantation but did not undergo surgery. Among the 64 patients, 49 patients (76.6% and 15% of those listed) died before an organ became available and 15 patients (23.4% and 4.6% of those listed) survived. The aetiology of ALF in the survived patients was drug-induced liver failure (8 patients), fulminant seronegative hepatitis (5 patients) and hepatitis B viral infection (2 patients).

At present, 693 patients are alive. Among the 281 patients who died, 260 patients (26.7%) died within 30 days of admission. When 30-day mortality for patients without transplantation was analysed against different aetiological factors, it was found that drug-induced liver failure had the best outcome with a 30-day mortality of 19.6%, followed by subacute necrosis (40%) and hepatitis A viral infection (41.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thirty-day mortality of non-transplanted patients according to aetiological subgroups

| Aetiology | Non-transplanted | 30-day mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Drug induced | 755 | 148 (19.6) |

| Seronegative hepatitis | 58 | 32 (55.2) |

| Hepatitis B | 26 | 13 (50) |

| Hepatitis A | 12 | 5 (41.7) |

| Acute Budd–Chiari | 15 | 8 (53.4) |

| Acute Wilson's disease | 0 | – |

| Subacute necrosis | 15 | 6 (40) |

| Miscellaneous | 93 | 48 (51.6) |

| Total | 974 | 260 (26.7) |

Discussion

This study is a large single centre experience of the outcome of ALF with and without liver transplantation. The study has reconfirmed that paracetamol overdose (61.2%) is the predominant cause of ALF in the UK. There was a steady increase in the number of patients with drug-induced liver injury from 1992 to 1996 (63 patients and 119 patients respectively). Thereafter there was a decline. This could be attributed partly to a change in central funding and partly to legislation on pack size. The frequency of paracetamol-related liver injury in the UK is much higher than that reported from the US (39%).4 In the US, the majority of paracetamol overdoses are believed to be accidental, whereas in the UK the reason for overdose is usually a suicide attempt.4 The likely reason is that paracetamol is the most widely used non-prescription analgesic in the UK. Paracetamol when consumed within recommended doses is unlikely to cause liver injury but in an overdose it is a common cause of severe liver injury because of its dose-related hepatotoxicity and the presence of associated factors such as alcohol use and starvation.11–13 However, one study showed that alcohol consumption protected against severe drug-induced liver injury.4 The same study confirmed that the presence of diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for the development of severe drug-induced liver injury.

The present study has shown that ALF as a result of Wilson's disease (100%) or seronegative hepatitis (68.8%) had a high transplantation rate as compared with drug-induced aetiology (10.4%). This finding was reflected in the study by Ostapowicz et al.4 This is because of the availability of an antidote (N-acetyl cysteine) for paracetamol-related liver injury and the ability of the liver to recover from paracetamol injury. Patients with paracetamol-induced ALF deteriorate rapidly resulting in multiple organ failure (MOF). Paradoxically if these patients do not fulfill the criteria for liver transplantation, the outcome is much better than for those with other causes.4,7,14 This again proved to be the case in our study, where 78.3% of patients with drug-induced ALF survived without transplantation. This could reflect the fact that the majority of our drug-induced ALF was because of paracetamol overdose, who have better outcome than the non-paracetamol drug-induced ALF. However, it was found by Bernal et al. that once they were listed for transplantation, they were at a greater risk of deterioration, although post-transplantation survival was not compromised.8 In our study, this could explain the fact that significantly fewer drug-induced ALF patients were transplanted (74.6%), as opposed to listed seronegative hepatitis patients (85.9%), because drug-induced ALF patients probably died before an organ became available. After viral-induced ALF, we found that survival without transplantation was over 50%. The study by Dhiman et al. analysed outcome of ALF as a result of viral hepatitis and reported a survival of 32.3% without transplantation.3 They concluded that the prognostic factors determining outcome in ALF-complicating viral hepatitis were age >50 years, presence of raised intracranial pressure at admission, prothrombin time of >100 s at admission and the onset of encephalopathy 7 days after onset of jaundice.3

In the current series, only 21.3% of patients with ALF received a liver graft. This was comparable to the results reported in earlier studies.4 This supports the fact that early aggressive supportive care is the key factor in the management of ALF. Nevertheless, it might reflect the fact that the majority of the patients with drug-induced liver failure were not severely poisoned. In our study, the overall survival after transplantation (70%) was higher than reported previously (41–67%).4,15–17 After transplantation, the favourable aetiological factors in terms of outcome were acute Wilson's disease, hepatitis B viral infection, seronegative hepatitis and drug-induced liver failure. The better survival rates could be attributed to the large number of patients with drug induced ALF, who were found to have better survival after transplantation based on previous reports.4 However, in the present study, seronegative hepatitis patients had significantly better 1-and 5-year survival after transplantation than the drug-induced ALF patients. This probably could be explained by the fact that drug-induced ALF is mostly as a result of suicidal intent and these patients having ongoing psychological issues. This could have an impact on the compliance of post-operative immunosuppression and hence on the complications and survival.

After transplantation, the mortality rate in the current series is 30% with a median survival of 57 months. In comparison with previous reports, the majority of the deaths were related to sepsis and MOF.18–20 Bernal et al. analysed the factors predicting mortality after transplantation and identified age >45 years, vasopressor requirement and use of high-risk grafts as independent risk factors.8 Wigg et al. studied the outcome after transplantation in 110 patients with seronegative acute liver failure. They found high donor body mass index, recipient age >50 years and non-caucasian recipient ethnicity as significant factors predicting early death.20

In conclusion, drug-induced liver failure still remains the most common cause of ALF in the UK. Aggressive early supportive care is associated with good survival in patients not listed for transplantation. Similarly in listed patients, liver transplantation when performed has good long-term survival.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr D.Mutimer, consultant hepatologist, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, UK for critical reading of the paper.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Bernal B. Changing patterns of causation and the use of transplantation in the United Kingdom. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:227–237. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM. Acute liver failure in the United States. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:217–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhiman RK, Seth AK, Jain S, Chawla YK, Dilawari JB. Prognostic evaluation of early indicators in fulminant hepatic failure by multivariate analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1311–1316. doi: 10.1023/a:1018876328561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SHB, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centres in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernal W, Wendon J. Liver transplantation in adults with acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2004;40:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal W, Wendon J, Rela M, Heaton N, Williams R. Use and outcome of liver transplantation in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1998;27:1050–1055. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devlin J, Wendon J, Heaton N, Tan KC, William R. Pre-transplantation clinical status and outcome of emergency transplantation for acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1995;21:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernal W, Cross TJ, Auzinger G, Sizer E, Heneghan MA, Bowles M, et al. Outcome after wait-listing for emergency liver transplantation in acute liver failure: a single centre experience. J Hepatol. 2009;50:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Grady JG, Schalm SW, Williams R. Acute liver failure: redefining the syndromes. Lancet. 1993;342:273–275. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91818-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiodt FV, Lee WM, Bondesen S, Ott P, Christensen E. Influence of acute and chronic alcohol intake on the clinical course and outcome in acetaminophen overdose. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:707–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K, Poulsen HE. Acute versus chronic alcohol consumption in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2002;35:876–882. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitcomb DC, Block GD. Association of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity with fasting and ethanol use. JAMA. 1994;272:1845–1850. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520230055038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandsaeter B, Hockerstedt K, Friman S, Ericzon BG, Kirkegaard P, Isoniemi H, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure: outcome after listing for highly urgent liver transplantation – 12 years experience in the nordic countries. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1055–1062. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koskinas J, Deutsch M, Kountouras D, Kostopanagiotou G, Arkadopoulos N, Smyrniotis V, et al. Aetiology and outcome of acute hepatic failure in Greece: experience of two academic hospital centres. Liver Int. 2008:821–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shakil AO, Kramer D, Mazariegos GV, Fung JJ, Rakela J. Acute liver failure: clinical features, outcome analysis, and applicability of prognostic criteria. Liver Transpl. 2006;6:163–169. doi: 10.1002/lt.500060218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiodt FV, Atillasoy E, Shakil AO, Schiff ER, Caldwell C, Kowdley KV, et al. Etiology and outcome for 295 patients with acute liver failure in the United States. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:29–34. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farmer DG, Anselmo DM, Ghobrial RM, Yersiz H, McDiarmid SV, Cao C, et al. Liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure: experience with more than 200 patients over a 17-year period. Ann Surg. 2003;237:666–675. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064365.54197.9E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barshes NR, Lee TC, Balkrishnan R, Karpen SJ, Carter BA, Goss JA. Risk stratification of adult patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Transplantation. 2006;81:195–201. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188149.90975.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wigg AJ, Gunson BK, Mutimer DJ. Outcomes following liver transplantation for seronegative acute liver failure: experience during a 12-year period with more than 100 patients. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:27–34. doi: 10.1002/lt.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]