Abstract

Cryosectioned tissues from snap-frozen samples offer the advantage of preserving proteins at the cellular and subcellular levels and maintaining overall cell integrity in the tissue of interest without the use of chemical fixatives. To prevent specific or nonspecific degradation of proteins by autolytic and/or proteolytic processes, it is common practice to immediately store frozen tissue sections obtained from a cryostat under cryogenic conditions, for example −80°C. Our laboratory recently challenged this widely held belief by extracting proteins from brain tissue samples that were archived for 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months at various storage conditions (frozen, ambient, or desiccated) without the use of chemical fixatives. Our results from immunofluorescent stains, immunoperoxidase stains, silver stains, and Western blot analyses demonstrated that snap-frozen, heat-dried tissue sections stored and desiccated at ambient laboratory conditions are comparable to frozen samples stored up to 6 months.

Keywords: protein snap-frozen heat-dried, desiccated, protein extraction, molecular biology, immunohistochemistry

The study design and analysis of ex vivo tissue samples determines the method by which the specimen is processed and preserved. Tissues used for morphologic or immunohistochemical analyses are frequently fixed with a common chemical fixative, such as formalin, and are embedded in paraffin. While formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens are well preserved and conveniently stored at ambient room temperatures, the cross-linking and sulfide bond formation caused by the fixative make them less compatible with current molecular techniques.1–3 Hence, epitope retrieval methodologies are used to recover the antigens; but recovery in some instances can be less than optimal.1,4,5 An alternative to the use of fixatives is the century-old method of freezing the tissue at subzero temperatures. Freezing the tissue provides a snapshot of the cells as they would appear at the time the sample was removed from the organism, while avoiding degradation of intracellular molecules via autolysis or similar mechanism.6–8 The vox populi among pathologists and histologists is to store snap-frozen tissue samples, which have been sectioned and desiccated, at −80°C. Typically, sectioned tissues are placed onto microscope slides (subbed or with electrostatic charge), dehydrated to remove moisture, and immediately stored at cryogenic temperatures.

The widely accepted belief that snap-freezing any tissue adequately preserves protein integrity at cellular and subcellular levels has served as the gold standard for molecular analysis.1–3,9 Ever since Altmann7 described cellular degradation in the form of proteolysis, the conventional method of cryogenic storage of frozen tissues has been used, and few deviations from this practice have been reported. However, the question remains whether sectioned tissue samples need to be maintained at freezing temperatures to preserve protein integrity. Challenging conventional practice, our laboratory asked whether proteins can be extracted from tissues, specifically brain sections, that were previously snap-frozen and stored at various conditions for a month or longer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Acquisition

Brain tissue was harvested from rats (n = 5) immediately after intravenous euthanasia (1.0 mL Euthasol I.C., Delmarva Laboratories Inc, Greenland, NH). Tissues were snap-frozen at −55°C in methylbutane cooled with dry ice. The tissue samples were submerged in the cryogenic solution for 14 seconds, removed, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) solution (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Brains were sectioned (Microm HM550 microtome/cryostat, Microm International, Walldorf, Germany) at 20 μm (used for protein extraction) and 10 μm (used for tissue staining) at −18°C. Three consecutive sections were placed onto electrostatic-charged microscope slides (Superfrost, VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA), and the slides were either dried on a microscope slide warmer (Lablyne, Melrose Park, IL) at 50°C for 45 minutes (noted as “With Heat,” or “w/h”) or merely air dried at room temperature for 15 minutes (noted as “Without Heat,” or “wo/h”). Samples were tested after being stored at the following conditions: frozen (−80°C), ambient (20°C and 45% relative humidity), and desiccated (20°C and <10% relative humidity) for 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months. The assay matrix is summarized in Table 1, where all tests were performed in triplicate.

TABLE 1.

Assay Matrix Studying the Effect of Different Storage Conditions on Brain Tissue Samples Over 6 months

| Sample | Storage Condition | Metrics | Tissue Stains (H&E, IP, and IF) | Silver Stain | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Without heat | |||||

| 1 Day | Frozen |

|

|

|

|

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 1 Week | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 1 Month | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 6 Months | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| With heat | |||||

| 1 Day | Frozen |

|

|

|

|

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 1 Week | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 1 Month | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

| 6 Months | Frozen | ||||

| Ambient | |||||

| Desiccated | |||||

H&E indicates hematoxylin and eosin; IF, immunofluorescence; IP, immunoperoxidase.

Tissue Preparation

Samples of tissue sections (20 μm) were excised under a dissecting microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a disposable 1.0 mL syringe and 27G 1/2″ needle (Becton Dickinson Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Specifically, the area of tissue to be removed (ie, striatum) was outlined with the needle, then a minute quantity of protein extraction buffer (PEB, T-PER, Pierce Biotechnology Inc, Rockford, IL) was pipetted (Finnpipette, ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) in 2.0 μL increments on the outlined section until the buffer immersed approximately half of the inscribed area. To both minimize tissue loss and ease transfer into a microcentrifuge tube (USA Scientific Inc, Ocala, FL), the tissue was removed from the slide using the 27G needle and combined with PEB. The tissue/PEB was carefully transferred to a 1.5 mL tube. Approximately, 150 μL of PEB without protease inhibitors was added to the semi-dried sample, and the tube was placed on ice. Immediately after sample preparation, the protein was extracted.

Protein Extraction

To minimize sample loss, the same 27G needle used to excise the tissue was used to aspirate the mixture 10 times, while cautiously avoiding introduction of excess air in the mixing process. This series was repeated using a 30G needle (Becton Dickinson Co) with the same syringe. The sample was agitated (Maxi Mix, Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA) for 60 seconds, and then centrifuged (Eppendorf model 5415C, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 minutes at 10,000 × G at room temperature (20°C). The supernatant was transferred into a clean microfuge tube, and the pellet was stored at −20°C. Supernatant total protein concentration was quantified with a microplate reader (Benchmark Plus, Bio-Rad Inc, Hercules, CA), via the Bradford method (minimal protein detection size of 4.5 kd), and normalized by area removed.

Silver Stain

Protein samples (total loading mass = 10.0 μg) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad Inc) at constant voltage (120 V) for approximately 45 minutes. The gel was silver stained as previously described,10 dried overnight using a commercial gel drying kit (Owl Inc, Portsmouth, NH), and imaged with a conventional flatbed scanner at 600 dpi on the following day.

Western Blot

Protein samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% Tris-HCl gel at constant voltage (120 V) for approximately 45 minutes. Proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Inc) overnight at 40 volts and 4°C. A 5% nonfat milk (NFM) blocking solution (Bio-Rad Inc) containing Tris-buffered saline with 0.01% Tween-20 (TBS-T) was applied to the membranes for 60 minutes at room temperature. The membranes were subsequently washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in TBS-T. The membranes were then examined for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity with a mouse anti-rat monoclonal antibody (Chemicon Inc, Temecula, CA) in a 5% NFM/TBS blocking solution (1:1000) overnight at 4°C with mild agitation (Orbit Shaker, Barnstead International). To normalize sample loading, the ubiquitous enzyme, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Chemicon Inc) blot was performed. Briefly, the membranes were incubated in mouse anti-rat GAPDH and 5% NFM/TBS-T at a 1:300 dilution overnight at 4°C with mild agitation. Expression of both TH and GAPDH was detected with 1:10,000 and 1:5000 dilution horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories Inc, Burlingame, CA) and chemiluminescent solution (Super Signal West Pico, Pierce Biotechnology Inc, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain

OCT-embedded, fresh, and archived brain sections were fixed in acetone and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as previously described.11

Immunoperoxidase Stains

OCT-embedded, fresh, and archived brain sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, and washed twice for 5 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with Tween-20 (PBS-T) washing solution. To block endogenous peroxidases, samples were incubated in 0.1% H2O2 in 1 × PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. After blocking for 60 minutes with serum blocking solution (10% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in 1 × PBS), the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with TH diluted at 1:500 in 1 × PBS. Samples were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in 1 × PBS, and incubated with a secondary antibody, Biotinylated Anti-Mouse (Vector Laboratories Inc, 1:100) for 30 minutes at room temperature. While the secondary antibody incubated, the avidin-biotinylated-peroxidase complex solution was prepared and stored at 4°C for 30 minutes before use. The secondary antibody was washed off with 1 × PBS 3 times for 5 minutes each, and subsequently incubated with avidin-biotinylated-peroxidase complex solution for an additional 30 minutes at room temperature. After a wash with 1 × PBS, a solution of 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole was applied to the samples for a maximum of 6 minutes, or until red reaction product developed. The reaction was terminated by a 1 × PBS wash. Finally, samples were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with aquamount and cover-slipped.

Immunofluorescent Stains

Brain tissue samples were either dual-labeled (fluorescent) with TH and MAP5B or labeled individually for GFAP with a 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain to evaluate epitope recognition. OCT-embedded brain sections (fresh and archived) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, and washed twice in PBS-T washing solution for 5 minutes. After blocking for 60 minutes with serum blocking solution (10% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in 1 × PBS), the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with TH diluted at 1:500 in 1 × PBS. Next, the sections were treated with horse anti-mouse Rhodamine red (Vector Laboratories Inc) secondary antibody (diluted 1:40 in PBS) for 60 minutes. After 3 PBS-T rinses, the tissues were blocked for 120 minutes with serum blocking solution (10% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in 1 × PBS), and incubated overnight at 4°C with MAP5B (a stable structural protein found in neurons) diluted at 1:500 in 1 × PBS. Next, they were treated with horse anti-mouse FITC (Vector Laboratories Inc) secondary antibody (diluted 1:40 in PBS) for 60 minutes. Samples tested for GFAP (stable structural protein found in glial, non-neuronal cells) activity were treated similarly, where samples were fixed, rinsed, and blocked as noted above and then incubated overnight at 4°C diluted at 1:500 in 1 × PBS. GFAP samples were treated with horse anti-mouse FITC (Vector Laboratories Inc) secondary antibody (diluted 1:40 in PBS) for 60 minutes. The signal was detected with DAPI fluorescent mounting media (Vector Shield, Vector Laboratories Inc). Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM-510 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using a plan-neofluar 40 × oil immersion lens, NA 1.3. Slides were scanned under the same conditions for magnification, laser intensity, brightness, gain, and pinhole size. Images were processed using the LSM 510 software version 3.2 SP2.

RESULTS

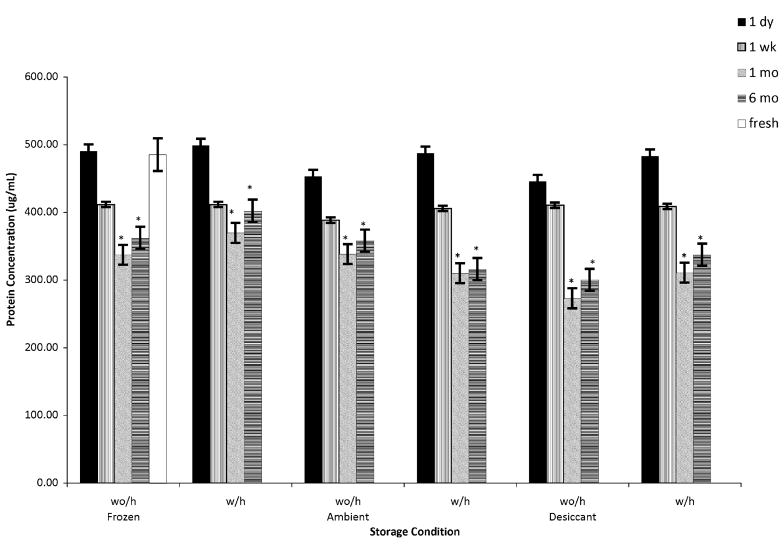

Protein extraction is possible from brain tissue sections after 6 months without cryogenic storage or chemical fixatives. Tissue sections stored with or without desiccant at ambient temperatures provide protein concentrations comparable to fresh samples after 6 months (Fig. 1), though ambient and desiccated samples provided statistically and significantly less protein per given volume as calculated against a normalized region removed. This reduction in protein concentration can be attributed to the technical difficulty in isolating tissues from the slide by hand, which resulted in minor loss of sample. Specifically, some pieces of the ambient and desiccated tissue sections possessed an electrostatic charge that at times were repelled off the needle tip by the minor electrostatic charge on the plastic microcentrifuge tube.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of normalized protein concentrations (μg/mL) extracted from 20 μm murine brain tissue sections stored at various conditions over a 6-month period. Frozen refers to tissue sections stored at −80°C, ambient refers to sections stored at room temperature (RT, ~22°C), and desiccated refers to sections stored at RT with low RH. Slides that were not placed on a slide warmer are noted as “wo/h” and those that were are noted as “w/h”. Error bars represent ±SEM. Statistically significantly difference, P<0.05 (Student t test), represented by *. RH indicates relative humidity; w/h, with heat; wo/h, without heat.

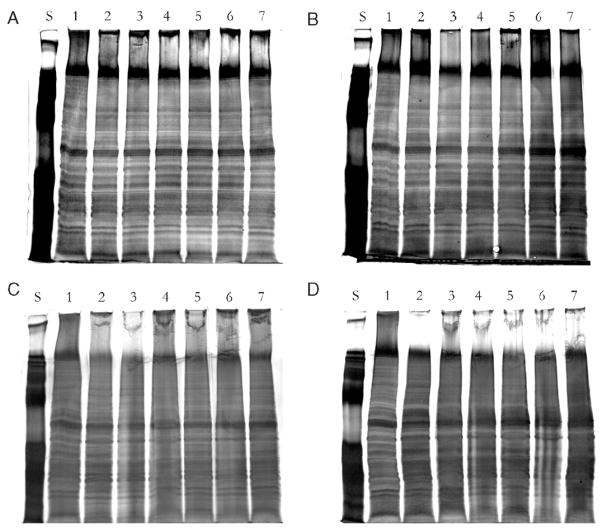

Proteins from tissues stored at ambient conditions after 6 months, particularly those desiccated, are similar to both fresh and frozen samples. Silver stain images from 1-day-old, 1-week-old, and 1-month-old brain sections stored at ambient conditions are almost indistinguishable from their fresh or frozen counterparts as they exhibit similar appearances in fractionation patterns while displaying the least change in band definition (Fig. 2). The most observable change in band profile was detected with the 6-month-old specimens, which displayed only a minor loss in band resolution as compared with fresh and frozen samples. Overall, sample bands appear sharp with minimal blurring, uncharacteristic of tissue that is undergoing proteolysis or complete degradation. These observations appear congruent with the results shown in Figure 1, demonstrating relatively identical protein detection and concentration over time at various storage conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Examination of protein degradation from 20 μm brain tissue sections at defined time points from various storage conditions. Extracted samples were resolved on a denaturing gel and stained by silver method. A, One-day-old samples. B, One-week-old samples. C, One-month-old samples. D, Six-month-old sample. S = Protein calibration standard. 1 = Fresh brain tissue section. 2 = Frozen brain tissue section (without heat). 3 = Ambient brain tissue section (without heat). 4 = Desiccated brain tissue section (without heat). 5 = Frozen brain tissue section (with heat). 6 = Ambient brain tissue section (with heat). 7 = Desiccated brain tissue section (with heat).

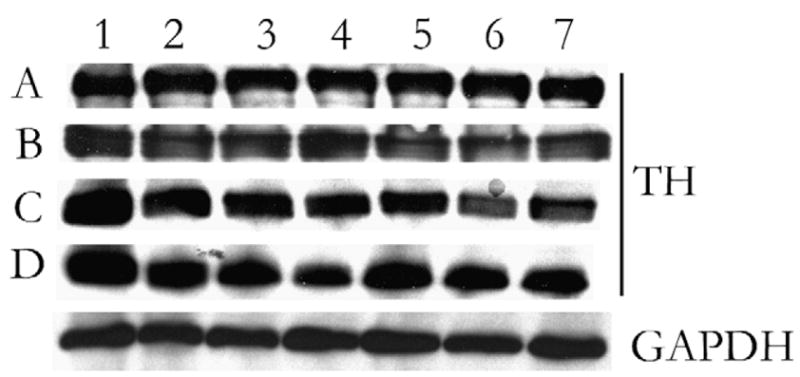

Epitopes from tissue that have been desiccating for over 6 months are comparable to fresh and frozen samples. All brain tissue sections display equal levels of TH over time (Fig. 3). Two bands were identified as possible rat-specific isoforms of TH.12 Furthermore, equal loading between all samples was verified by GAPDH detection.

FIGURE 3.

Demonstration of epitope detection of target protein extracted from 20 μm brain tissue sections at defined time points from various storage conditions. Samples were resolved on a denaturing gel and Western blot performed for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). GAPDH served as internal loading control, 1-month samples shown is representative. A, One-day-old sample. B, One-week-old sample. C, One-month-old sample. D, Six-month-old sample. 1 = Fresh brain tissue section. 2 = Frozen brain tissue section (without heat). 3 = Ambient brain tissue section (without heat). 4 = Desiccated brain tissue section (without heat). 5 = Frozen brain tissue section (with heat). 6 = Ambient brain tissue section (with heat). 7 = Desiccated brain tissue section (with heat). GAPDH indicates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

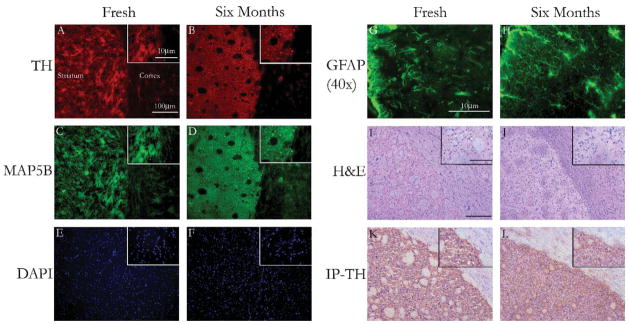

Immunofluorescent stains for TH and MAP5B or GFAP proteins remain unchanged across various aged brain sections. Immunoperoxidase stains were equally readily identifiable, and displayed minimal differences between fresh and desiccated samples. Hematoxylin and eosin stains display minimal changes after 6 months as well. Dual TH and MAP5B or GFAP staining was readily detectable after 6 months desiccation compared with fresh sample (Figs. 4A–H). Here, even astrocytic processes were easily seen after 6 months of desiccated storage. A negative control slide (only secondary antibodies added) displayed no activity (data not shown). After 6 months, eosin staining was reduced compared with fresh sample, yet basophilic structures, in particular, the cell nucleus had comparable hematoxylin staining. Additionally, nuclear morphology appeared consistent between samples (Figs. 4I, J). Similarly observed with immunofluorescent stains, immunoperoxidase staining revealed little change (Figs. 4K, L).

FIGURE 4.

Photomicrographs of brain tissue sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), immunoperoxidase, or immunofluorescences stains. Using a rat stereotaxtic atlas15 as a guide, all samples were taken at approximately bregma 0.72 mm (A←P), at a junction between striatum and cortex. A, C, and E, Fresh brain tissue section dual stain against TH and MAP5B, with nuclear counter stain. B, D, and F, Tissue section from 6-month-old desiccated samples with identical stains. G, Fresh brain GFAP stain. H, GFAP stain of sample after stored in desiccated condition for 6 months. I, Fresh brain H&E stain. J, H&E stain of sample after stored in desiccated condition for 6 months. K, Fresh brain immunoperoxidase stain for TH. L, immunoperoxidase stain for TH of sample after stored in desiccated condition for 6 months. TH = tyrosine hydroxylase, MAP5B = neuron, GFAP = glia (non-neuronal), DAPI = nuclear stain. Photomicrographs were taken at 2 different magnifications, unless otherwise noted, one at 10 × and another at 40 × (shown as inset).

DISCUSSION

Concentration of protein from the various samples, though calculated to be statistically different between ambient and desiccated samples, may not have reached a statistically significant difference if the tissue collection processes did not prove to be as difficult. Dissimilarity in calculated protein concentration notwithstanding, the integrity of proteins extracted from brain tissue sections stored at ambient condition stored with or without desiccant tissues over 6 months appeared similar to fresh and frozen samples as evidenced by the silver stain, a method understood to be more sensitive than Coomassie.10 Minor loss of definition was observed after a month of storage, yet desiccation at room temperature was well defined and comparable to either fresh or frozen samples. Only, after 6 months of storage at ambient temperatures was degradation evident, yet if products of complete proteolysis had been present the lane in question would have displayed a smear, which it did not.

Western blot analysis was performed to determine whether the epitopes of interest remained recognizable. We selected an enzyme as the protein of interest because enzymes are known to be potentially sensitive to decomposition or degradation at ambient conditions, that is, room temperature. The chosen epitope target was TH, a critical enzyme with various levels of activity present in all catecholaminergic cells, especially in tissues that react to the sympathetic response, such as brain, heart, and kidneys.13 Additionally, it is worth noting that the different molecular weight bands observed for TH can be explained by the recent evidence that 2 isoforms of TH exist in the rat whereas only 1 isoform is known to be produced in subprimate species.12–14 To normalize sample loading, the membranes were blotted for GAPDH, a ubiquitous housekeeping protein found in almost all tissues. Additionally, signal intensities of all tissues from fresh to 6 months appear equivalent, with no detectable loss from archived specimens.

Immunofluorescent results demonstrated no difference in signal intensity over time. Both MAP5B and TH stains/signals counterstained with DAPI remained consistent, as well as easily recognizable. As compared with fresh samples, astrocytic processes of GFAP-stained specimens were clearly identifiable even after 6 months desiccation. To explain why the investigated proteins from heat-dried, snap-frozen tissue sections stored at ambient condition, in particular the desiccated ones, do not appear degraded and epitopes of interest remain detectable, we suggest the following: First, proteosome-based degradation is interrupted, where either the prolonged exposure to 50°C or air-drying for 15 minutes may have potentially affected the ability of proteosome/ubiquitin complex to efficiently degrade proteins, instead of mere denaturation. Second, cellular desiccation due to a combination of prolonged elevated temperatures and thin tissue section impedes cellular processes, including action of degradative enzymes. Third, a combination of attenuated degradative process and the absence of water have altered the functional structures of various enzymes, which typically produce irreversible damage. Fourth, proteins in general, may simply be more stable at ambient conditions than they have been previously perceived.

From the present experimental results, we can draw several conclusions that appear to contradict the central dogma of snap-frozen heat-dried tissue section storage. First, it is possible to extract proteins from brain tissue section with minor indication of degradation after 6 months, as evidenced by silver stains, regardless of storage conditions. Next, the investigated epitopes (TH, MAP5B, GFAP, and GAPDH) were successfully detectable in the target tissues as shown by immunofluorescence, immunoperoxidase, and Western blots. With the preceding statements in mind, we suggest that snap-frozen heat-dried tissue sections may be stored at ambient, desiccated conditions for up to 6 months at minimum without significant damage to protein integrity. Albeit these results may be inapplicable to all proteins due to their variable stabilities and also the limited number examined, proteins of interest should be tested individually to verify the suitability of this method. Future studies include examination of samples stored for more than a year using the same techniques, assessment of competition assays, and investigation of less stable macromolecules.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Florence Hofmann, Dr Jun Yang, Dr Jean-Michel Maarek, Ernesto Barron, Anthony Roderiguez, Wen Wei, Jefferey Scehnet, Ariel Schvartz, and Adel Kardosh for their support, technical assistance, and constructive criticism in the writing and development of this manuscript.

Supported by NCCAM (5R24AT002681), a core grant from NEI (5P30EY003040), and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

References

- 1.Chu WS, Liang Q, Liu J, et al. A nondestructive molecule extraction method allowing morphological and molecular analyses using a single tissue section. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1416–1428. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlmutter MA, Best CJ, Gillespie JW, et al. Comparison of snap freezing versus ethanol fixation for gene expression profiling of tissue specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:371–377. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60534-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie JW, Best CJ, Bichsel VE, et al. Evaluation of non-formalin tissue fixation for molecular profiling studies. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64864-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi SR, Key ME, Kalra KL. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:741–748. doi: 10.1177/39.6.1709656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi SR, Cote RJ, Taylor CR. Antigen retrieval techniques: current perspectives. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:931–937. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris RJ. Preservation of biological materials by freeze-drying. Nature. 1951;168:851–853. doi: 10.1038/168851a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altmann R. Die Elementarorganism und ihre Beziehungen Zu den Zellen (The Elementary Organism and Their Relations With the Cells) Leipzig: Verlag Von Veit & Comp; 1894. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boe J, Greaves RI. Observations on the biological properties of B.C.G. treated by freeze-drying. Acta Tuberc Scand. 1950;24:38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Mechanisms of intracellular protein breakdown. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51:335–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrissey JH. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Anal Biochem. 1981;117:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehan DaH B. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. 2. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schussler N, Boularand S, Li JY, et al. Multiple tyrosine hydroxylase transcripts and immunoreactive forms in the rat: differential expression in the anterior pituitary and adrenal gland. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:846–854. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490420613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grima B, Lamouroux A, Blanot F, et al. Complete coding sequence of rat tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:617–621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haycock JW. Species differences in the expression of multiple tyrosine hydroxylase protein isoforms. J Neurochem. 2002;81:947–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotactic Coordinates. 4. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]