Abstract

Although the role of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism to eicosanoids has been well established in allergy and asthma, recent studies in neoplastic cells have revealed that AA remodeling through phospholipids impacts cell survival. This study tests the hypothesis that regulation of AA/phospholipid-remodeling enzymes, cytosolic phospholipase A2 α(cPLA2-α, gIVαPLA2) and CoA-independent transacylase (CoA-IT), provides a mechanism for altered eosinophil survival during allergic asthma. In vitro incubation of human eosinophils (from donors without asthma) with IL-5 markedly increased cell survival, induced gIVαPLA2 phosphorylation, and increased both gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT activity. Furthermore, treatment of eosinophils with nonselective (ET18-O-CH3) and selective (SK&F 98625) inhibitors of CoA-IT triggered apoptosis, measured by changes in morphology, membrane phosphatidylserine exposure, and caspase activation, completely reversing IL-5–induced eosinophil survival. To determine if similar activation occurs in vivo, human blood eosinophils were isolated from either normal individuals at baseline or from subjects with mild asthma, at both baseline and 24 hours after inhaled allergen challenge. Allergen challenge of subjects with allergic asthma induced a marked increase in cPLA2 phosphorylation, augmented gIVαPLA2 activity, and increased CoA-IT activity. These findings indicate that both in vitro and in vivo challenge of eosinophils activated gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT, which may play a key role in enhanced eosinophil survival.

Keywords: phospholipase A2, coenzyme A–independent transacylase, eosinophil, asthma, enzyme inhibitors

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

These findings indicate that both in vitro and in vivo challenge of eosinophils activated gIVaPLA2 and CoA-IT, which may play a key role in enhanced eosinophil survival. Understanding the activation of these inflammatory cells in lung diseases such as asthma may provide insight into therapeutic targets to improve clinical management.

A primary mechanism involved in the resolution of lung inflammation is thought to be the death and clearance of eosinophils. If allowed to accumulate in tissues, eosinophils can release a wide variety of proinflammatory mediators including cytotoxic granule proteins, lipid mediators, and cytokines, thereby exacerbating inflammatory diseases such as allergic asthma (1). In vivo, normal induction of eosinophil death by apoptosis facilitates their clearance by macrophages and other phagocytic cells (2). However, various growth factors and cytokines released during inflammation render eosinophils more resistant to apoptosis (3).

In allergic diseases, production of the cytokines IL-5 and GM-CSF delay eosinophil apoptosis (4). IL-5 exposure causes eosinophils to enter a nonresting state, referred to as priming. In the primed state, intracellular pathways are partially activated, decreasing the time necessary for eosinophils to release granules and produce lipid mediators and cytokines in response to a second agonist. Thus, during diseases such as allergic asthma, priming cytokines such as IL-5 prolong the life span of the infiltrating eosinophils by delaying apoptosis, thereby heightening their potential to cause tissue damage. This concept has been supported by in vivo studies that show that reduced apoptosis of sputum eosinophils is related to increased clinical severity of allergic asthma (5), and also by observations of apoptotic airway eosinophils in vivo (6). Together, these findings provide evidence that the regulation of eosinophil apoptosis plays a critical role in the resolution of inflammation in diseases such as asthma.

While AA is predominantly recognized as a substrate yielding biologically active metabolites such as eicosanoids, recent studies from cancer literature have demonstrated that levels of free (unesterified) AA (controlled by AA-phospholipid turnover) can regulate apoptosis in several cell types (7–9). More specifically, these studies have shown that blockage of AA-phospholipid remodeling leads to a marked increase in intracellular AA and cellular apoptosis.

There are two known pathways which regulate intracellular levels of AA via its incorporation and remodeling into different phospholipid pools. The first has been termed a “high affinity–low capacity” pathway (10). Cells use this pathway to rapidly incorporate and remodel AA through various glycerophospholipids. The predominant enzymes in this pathway include long chain fatty-acid ligase (FACL, or AA-CoA ligase), lysophospholipid:acyl-CoA acyltransferase, and acyl-CoA independent transacylase (CoA-IT) (11). Both AA-CoA ligase and CoA-IT show a high specificity for arachidonate relative to other fatty acids. Recent studies by Zarini and colleagues have demonstrated that reacylation of free AA back into phospholipids using lysophospholipid:acyl-CoA acyltransferase and AA-CoA ligase is critical in controlling free AA levels in primed and stimulated neutrophils (12).

There is a second “low affinity–high capacity” pathway that is used when cells encounter high concentrations of AA. In this pathway, AA is ultimately incorporated into triacylglycerides and diarachidonoyl phospholipids using the classical de novo glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway. Along with others, we have demonstrated that inflammatory cells accumulate triglycerides in cellular lipid bodies at sites of inflammation using this pathway (13).

The generation of lysophospholipid acceptors necessary to drive these de novo synthesis and remodeling pathways is thought to be accomplished by the action of phospholipase A2(s). The identity of the phospholipase is not clear at this time but is potentially different under various cellular situations. Evidence suggests that the group VI (calcium independent) iPLA2 may function in this capacity in many unstimulated cells (14), whereas the gIVαPLA2 (calcium dependent cytosolic PLA2, cPLA2) is activated in other cell types, especially leukocytes (15). In colorectal tumors, gIVαPLA2 levels and function have been associated with cancer pathogenesis (16). Many of the effects of gIVαPLA2 in neoplastic cells have been postulated to be due to effects of elevating free AA and its subsequent effects on mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis.

Given the growing body of work on AA-phospholipid remodeling enzymes and apoptosis in the cancer cells, the current study was performed to better understand how these enzymes impact eosinophil survival and apoptosis during inflammation. These data suggest that AA-phospholipid remodeling orchestrated by CoA-IT and gIVαPLA2 may function to regulate eosinophil apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Cell buffer (Hank's with calcium and magnesium, HBSS) was purchased as a 10X stock from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) and was diluted fresh daily with ultrafiltered deionized water (Pure Flow, Mebane, NC). Isolymph was obtained from Gallard Schlesinger (Carle Place, NY). Leupeptin and pepstatin A were purchased from Peninsula Labs (Belmont, CA). Protein determinations were made with a Pierce BCA assay (Rockford, IL). Immobilon PVDF, chemiluminescence developing reagents, 1-palmitoyl-2 [14C] arachidonoyl-glycerophosphocholine, and [3H]-arachidonic acid were purchased from PerkinElmer/New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). Peroxidase-linked goat-anti-rabbit IgG was obtained from ICN/Cappel (Durham, NC). Partially phosphorylated (insect cell expressed) recombinant human cPLA2 was a kind gift from Dr. Ruth Kramer (Eli Lily, Indianapolis, IN). IL-5, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, Annexin V, and caspase 8 and 9 fluorometric substrates were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-Fas antibody (CD-95) was from Immunotech, Inc., (Westbrook, ME), SK&F 98625 as described from Dr. Floyd Chilton (17), Diff-Quik stains from Baxter (McGraw Park, IL), and 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (Et-18-O-CH3) from Alexis (San Diego, CA). All high-performance liquid chromatography–grade organic solvents were from Fisher Chemicals (Atlanta, GA) and unless specified, other substances were the best reagent grade as purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Silica Gel G thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates were from Analtech (Newark, DE).

Asthma Subject Selection

Adult subjects with mild atopic asthma and normal, nonsmoking subjects without history of chronic illness or allergy were studied in protocols approved by our Institutional Review Board. A written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Each subject with asthma met the criteria proposed by the American Thoracic Society to define asthma, having documented reversible airflow obstruction demonstrated by an increase in FEV1 of more than 15% after β-agonist inhalation, or episodic symptoms of airflow obstruction, including cough, dyspnea, and wheezing, consistent with reversible airflow obstruction, without a significant cigarette smoking exposure history (< 5 pack-years). Anti-inflammatory medications, including inhaled and systemic corticosteroids, were withheld for at least 6 weeks before study initiation. Inhaled β-agonists (except salmeterol) were withheld for 6 hours, and salmeterol and theophyllines were withheld for 24 hours before each study.

Allergen Challenge

Inhaled allergen challenges were performed in each subject with asthma as previously described (18) using cat dander (Felis domesticus), dust mite (Dermatophagoides farinae) (both from Greer Laboratories, Inc., Lenoir, NC), or standardized cat hair (ALK Laboratories, Inc., Wallingford, CT). All subjects demonstrated both skin test reactivity to the specific allergen, had a clinical history compatible with allergic asthma, and a PC20 methacholine less than or equal to 8 mg/ml. Blood was drawn before the administration of allergen and at either 6 hours or 24 hours after challenge. Subjects were monitored for a minimum of 10 hours after inhaled allergen challenge, including determination of the late asthmatic response (LAR, defined as a drop in FEV1 of at least 15%), which occurred in all subjects 3 to 10 hours after challenge and which persisted for more than 30 minutes.

Eosinophil Isolation

Granulocytes were isolated from heparinized venous blood by density gradient centrifugation through Isolymph (Gallard Schlesinger, Carle Place, NY) as described (19). Eosinophils were then purified by negative immunomagnetic selection as described (20). The average preparation of eosinophils was more than 95% pure by this method. Enough eosinophils were available from each blood sample for to perform either gIVαPLA2 Western blots, measurement of cPLA2 activity, or measurement of Co-A-IT activity. For human donors without asthma, subjects with absolute peripheral blood eosinophil counts below 350 per mm3 were used.

Cytokines and CoA-IT Inhibitors

IL-5, TGF-β, and anti-Fas antibody (CD-95) were used at final concentrations of 0.05 ng/ml, 0.5 ng/ml, and 10 μg/ml, respectively. SK&F 98625 was diluted in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 20 μM and 40 μM. 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (Et-18-O-CH3) was diluted in EtOH and used at 10 μM and 25 μM final concentrations.

Cell Isolation, Stimulation, and Fractionation

Isolated eosinophils were incubated in RPMI 1640 media with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 10% FBS, and L-glutamine at 1–2 × 106 cells/ml at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were treated with recombinant human IL-5 in RPMI 1640 media at the concentrations and times described in Results; control cells received no IL-5 supplement. For cPLA2 experiments, stimulation of cells was terminated as described (21).

Phospholipase A2 Assays

cPLA2 enzymatic activity was assayed by the hydrolysis of 1-palmitoyl-2 [14C] arachidonoyl-glycerophosphocholine ([14C] AA-GPC) (19), using 80 μg of cytosolic protein and terminated after 20 minutes by organic extraction as described (21, 22).

CoA-IT Assay

Eosinophils were washed once in PBS without Ca++ or Mg++ and were sonicated at 2.5 × 107 cells/ml in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mM EDTA (CoA-IT buffer). CoA-IT enzymatic activity was assayed by the formation of phosphatidylcholine from radiolabeled lysophosphatidylcholine (acceptor assay), using 0.5 μCi 1-[3H] alkyl-2-lyso-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine as a tracer as described (15). Reactions contained 892 pmoles of unlabeled lysophosphatidylcholine in CoA-IT buffer with 50 μg of cell sonicate. After 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C, the reactions were terminated by organic extraction, followed by TLC. Bands corresponding to 1-[3H]alkyl-2-lyso-GPC and 1-[3H]alkyl-2-acyl-GPC were identified and scraped, and radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation.

Labeling of Cellular Glycerophospholipids with [3H]-AA and Analysis of Labeled Products

Eosinophil glycerophospholipids were labeled with [3H]-AA as described (9). Briefly, cells were incubated with 1 μCi of [3H]-AA (New England Nuclear) per 1 × 106 cells in HBSS containing essentially fatty acid–free human serum albumin (250 μg/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C and washed several times to remove excess label. These pulse-labeled cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in RMPI to allow AA redistribution through glycerophospholipids before inhibition with 20 or 40 μM SK&F 98625 for an additional 24 hours. Cells were centrifuged, lipids extracted (22), and AA distribution analyzed by TLC on Silica Gel G plates resolved with heaxane:ether:formic acid (90:60:6) (21).

PAGE and Western Analysis

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western analysis was performed on eosinophil cytosolic fractions to determine the degree of gIVαPLA2 phosphorylation. Fifty micrograms of eosinophil cytosolic protein were resolved on 7.5% PAGE with SDS. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon PVDF membrane. A rabbit, anti-peptide antibody was raised against peptide residues 443 to 462 of gIVαPLA2 as described (19, 21), affinity purified, and used as described (21). Blots were developed and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Densitometry of film bands was obtained using a Pharmacia Biotech Image Master software system (Uppsala, Sweden) coupled to a Sharp X 32F6 scanner. Images in this article are from single experiments representative of –three to nine experiments per condition and were reproduced here by scanning an ECL film using a Hewlett -Packard Scanjet 5370C (Palo Alto, CA).

Apoptosis Assays: DNA Ladders

Apoptotic induction of DNA fragmentation ladders was assayed using a Gentra Puregene DNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions as described (20) and resolved by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide detection.

Phosphatidylserine Exposure

Annexin V binding to newly exposed cell surface phosphatidylserine was measured using an R&D Systems protocol without a final wash step. At least 100 cells per sample were quantitated utilizing a Zeiss inverted fluorescence microscope (Thornwood, NY).

Cell Volume

Eosinophil cell volumes were quantitated by a Coulter counter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL), counting 10,000 cells per condition.

Light Microscopy

Eosinophil cytospins were prepared and stained in Baxter's Diff-Quik Stains and examined under light microscopy (> 100 cells each) for morphologic changes, including nuclear rounding and shrinkage (20).

Membrane Integrity

Membrane integrity was measured by examining the exclusion of trypan blue by light microscopy.

Caspase Activity

Caspase 8 or 9 activity was measured using an R&D Systems protocol with samples incubated for 2 hours with fluorescent conjugated caspase-specific peptide substrates, IETD-AFC substrate for caspase 8 and LEHD-AFC substrate for caspase 9. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation of 400/505 nm excitation/emission on an SLM 8000C spectrofluorometer.

Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM, where n ≥ 3 separate blood donors. Significance (P ≤ 0.05 unless stated) of asthma subject data before and after allergen challenge was evaluated by paired t test unless noted. Comparison of patient data to that of control subjects without asthma was evaluated by unpaired t test.

RESULTS

Influence of In Vitro Treatment with IL-5 on gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT

IL-5 has been documented to prolong eosinophil survival and to prime a number of eosinophil functions including oxidant production and LTC4 release (23). Initial in vitro experiments confirmed that IL-5 (50 ng/ml) prolonged the survival of peripheral blood eosinophils in tissue culture for over 50% of the cells at 96 hours in vitro (our unpublished data).

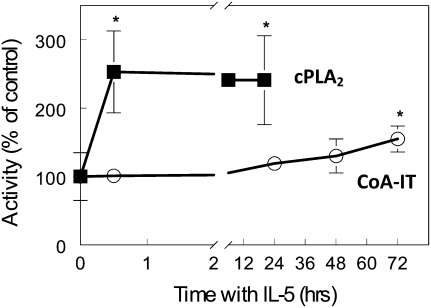

In several neoplastic cells, enhanced cell survival and proliferation have been associated with a notable increase in AA-phosopholipid remodeling. Consequently, the influence of IL-5 on the activity of enzymes that control AA-phospholipid remodeling in leukocytes was measured. Measurement from cell sonicates demonstrated that incubation of normal donor eosinophils with 100 pg/ml IL-5 activated cPLA2. In vitro, IL-5 activated cPLA2 activity (255 ± 60% increase over unstimulated control cells) within 30 minutes of providing the cytokine (Figure 1, squares). This doubling of activity was maintained for the 20 hours in which it was examined (241 ± 65%). Results with IL-5 were normalized relative to the paired control (no IL-5) sample at each time point.

Figure 1.

IL-5 activated eosinophil cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) and CoA-independent transacylase (CoA-IT) with different kinetics in vitro. Eosinophils from healthy individuals without asthma were isolated and incubated with IL-5 for the indicated periods in cell culture, harvested, fractionated, and either cPLA2 or CoA-IT enzymatic activities assayed as described in Materials and Methods. IL-5 (100 ng/ml) significantly increased cPLA2 activity (squares) within 30 minutes and maintained that activation for at least 20 hours. However, IL-5 failed to activate CoA-IT (circles) within 30 minutes and required at least 72 hours (at 50 ng/ml) to significantly increase CoA-IT activity in cultured eosinophils. *P = 0.05 by paired t test versus unstimulated 0-minute samples.

IL-5 also increased CoA-IT activity; however, these changes were not observed until later in the time course (Figure 1, circles). At 72 hours there was a significant increase (155 ± 19%, P < 0.05) in CoA-IT activity when compared with non–IL-5–treated cells.

Effects of CoA-IT Inhibitors on the Apoptosis of Eosinophils

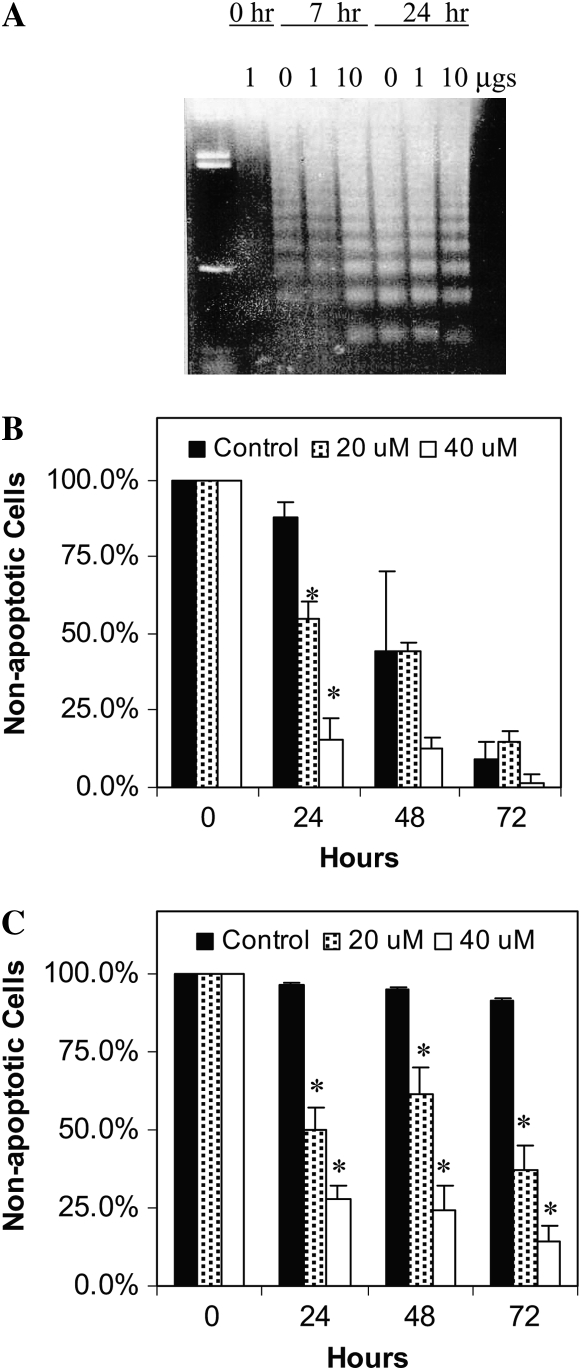

Blocking AA-phospholipid remodeling using CoA-IT inhibitors has been reported to induce apoptosis in several neoplastic cell lines (24). Therefore, the next set of experiments examined the effect of CoA-IT inhibitors on eosinophil apoptosis. The CoA-IT inhibitor, SK&F 98625, is a reversible antagonist of CoA-IT with an IC50 of 5–10 μM in cell-free assays and an IC50 of 15 to 25 μM in whole cells (25). In initial experiments, peripheral blood eosinophils were isolated and cultured with increasing concentrations of SK&F 98625 and then apoptosis was monitored by examining the formation of 200–base pair fragments of DNA into DNA ladders. DNA fragmentation was evident as SK&F 98625 concentration increased, consistent with apoptotic activation of nuclease activity (Figure 2A). This induction of apoptosis was confirmed by measuring the translocation of phosphatidylserine (PS) to the surface of the plasma membrane of eosinophils cultured in the presence and absence of IL-5. Figure 2B shows that SK&F 98625 caused significant concentration-dependent increases in PS translocation 24 hours after treatment. Other apoptotic characteristics observed included changes in cell volume, morphology, and trypan blue exclusion (our unpublished data). All of these assays confirmed that SK&F 98625 induced apoptosis of eosinophils. Similarly, when eosinophils were incubated with IL-5, fewer cells became apoptotic (solid bars in Figure 2C). However, SK&F 98625 (20 μM or 40 μM) completely reversed the capacity of IL-5 to increase eosinophil survival, inducing significant apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

The CoA-IT inhibitor, SK&F 98625, induced eosinophil apoptosis in vitro. (A) Human eosinophils were cultured for 7 to 24 hours alone, or with SK&F 98625 at 0, 1, or 10 μM (as marked). DNA was harvested and apoptosis was indicated by the banding pattern of the resulting DNA ladder (3 μg total DNA per lane, one example shown). (B) Human eosinophils were cultured for 0 to 72 hours alone (control, solid bars), or with SK&F 98625 at 20 μM (hatched bars) or 40 μM (open bars). Apoptosis was measured as the percent of eosinophils expressing surface phosphatidylserine (annexin V binding). Samples were taken at 0, 24, 48, or 72 hours. *P < 0.05 between control and SK&F 98625 at each time point. (C) The experiment was repeated by adding IL-5 alone (50 pg/ml, solid bars) to human eosinophils in culture for 0 to 72 hours or in combination with SK&F 98625 at 20 μM (hatched bars) or 40 μM (open bars). Apoptosis was again measured as the percent of eosinophils expressing surface phosphatidylserine. *Significant differences of P < 0.05 between IL-5 alone and SK&F 98625 + IL-5 at each time point (n = 3–4 separate cell preparations).

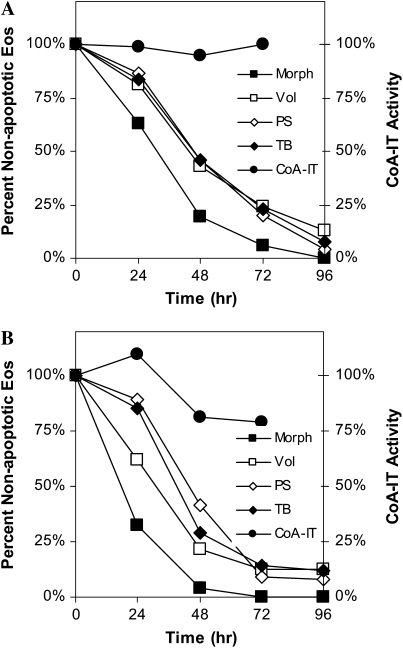

Et-18-O-CH3, a nonselective inhibitor of CoA-IT (25), also rapidly induced apoptosis in control eosinophils (Figure 3A) and completely reversed IL-5–induced increases in eosinophil survival measured by cell volume changes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The CoA-IT inhibitor, Et-18-O-CH3, induced eosinophil apoptosis in vitro. (A) Human eosinophils were cultured for 0 to 72 hours in media alone (control, solid bars), or with Et-18-O-CH3 10 μM (hatched bars) or 25 μM (open bars). Apoptosis was determined as the percent of eosinophils with decreased cell volume as shown by Coulter counter measurements. Samples were taken at 0, 24, 48, or 72 hours. (B). Eosinophils were cultured for 0 to 72 hours in media with IL-5 alone (50 pg/ml, solid bars), or combination with Et-18-O-CH3 at 10 μM (hatched bars) or 25 μM (open bars). Apoptosis was determined as the percent of eosinophils with decreased cell volume as shown by Coulter counter measurements. Samples were taken at 0, 24, 48, or 72 hours. Significant differences of P < 0.05 were seen between eosinophils treated with IL-5 and Et-18-O-CH3 + IL-5 after 48 hours, as indicated by asterisks (n = 3–4 separate cell preparations per assay).

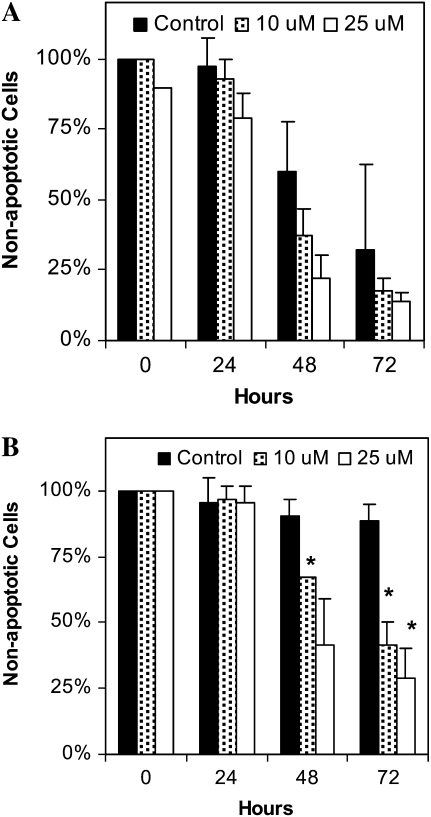

To determine the impact of CoA-IT inhibition on AA distribution in the eosinophils, cells were pulse-labeled with [3H]-AA before inhibition with SK&F 98625. After 48 hours of total culture time, AA was elevated in the combined free fatty acids plus triglyceride fraction, and increased further upon incubation with the CoA-IT inhibitor (Figure 4). There was a corresponding decrease in the AA content of the phospholipid pool (not shown). Even the untreated cells have high levels of unesterified AA after the total 48 hours in culture, more so in this primary cell than seen in immortalized tumor cell lines in the literature. This occurs at a point at which approximately 50% of the eosinophils are apoptotic, which is consistent with the hypothesis that limiting AA remodeling causes increased AA and affects apoptosis in the eosinophils.

Figure 4.

The CoA-IT inhibitor, SK&F 98625, induced AA accumulation in eosinophils in vitro. Human eosinophils were pulse-labeled with [3H]-AA for 1 hour, washed, and then incubated for an additional 24 hours to allow isotopic equilibrium through all glycerophospholipid classes and subclasses. Subsequently, cells were cultured for an additional 24 hours alone or with SK&F 98625 at 20 μM or 40 μM. Cellular glycerolipids were extracted and separated in a neutral lipid TLC system. Significant AA accumulated in the combined free fatty acid and triglyceride fraction with a corresponding decrease in AA in the phospholipid fraction (PL). *P < 0.04 versus no inhibitor, n = 3.

Caspase Activation by CoA-IT Inhibitors

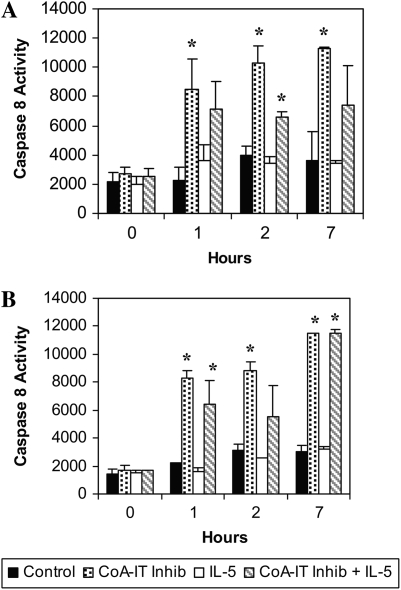

Caspases 8 and 9 are activated by diverse pro-apoptotic agents, and this activation has been shown to be a key early and committed step in the apoptotic pathway. Caspase activity was measured in eosinophils after CoA-IT inhibitor addition using two fluorogenic substrates. Caspase 8 activity (Figure 4A) and caspase 9 activity (Figure 4B) remained low in untreated eosinophils throughout the 7-hour experiment. IL-5 did not influence caspase 8 and 9 activity when compared with untreated eosinophils (Figures 4A and 4B). Caspase 8 and 9 activities in eosinophils were elevated at 1 hour after addition of SK&F 98625 (40 μM) and remained elevated throughout the 7-hour experiment. Activation of caspases by SK&F 98625 was more rapid than several other apoptosis-inducing agents including Fas ligand, TGF-β, and the F1-F0-ATPase inhibitor, oligomycin (data not shown). A similarly rapid activation of caspase 8 and 9 was observed after CoA-IT inhibitor treatment of IL-5–primed eosinophils (Figures 5A and 5B). These data revealed that CoA-IT inhibitors are potent and rapid inducers of caspase 8 and 9 activity as an early step in apoptosis in both control and IL-5–primed eosinophils.

Figure 5.

Caspase 8 and 9 are activated in eosinophils treated with SK&F 98625. Eosinophils were cultured with media alone (control, solid bars), SK&F 98625 40 μM (stippled bars), IL-5 (50 pg/ml, open bars), or with both IL-5 and SK&F 98625 (hatched bars) for times of 0, 1, 2, and 7 hours and then lysed. Lysates were incubated with fluorogenic substrates for (A) caspase 8 or (B) caspase 9, and fluorescence intensity was measured. Significant differences of P < 0.05 were seen between media controls and SK&F 98625–treated eosinophils (as noted by asterisks). Similar significant differences of P < 0.05 were also seen between eosinophils treated with IL-5 alone and those treated with SK&F 98625 + IL-5 (n = 3–7 separate cell preparations per condition).

Influence of Apoptosis-Inducing Agents on CoA-IT Activity

To determine if apoptosis caused by other apoptosis-inducing agents is associated with a change in CoA-IT activity, eosinophils were cultured with either the cytokine TGF-β (0.5 ng/ml) or Fas ligand. In both cases eosinophils underwent apoptosis at an increased rate compared with untreated cells (Figure 6). CoA-IT enzymatic activity remained similar to control values throughout the 72-hour time course. Together these data suggest that although blocking CoA-IT activity can induce apoptosis, a blockage in CoA-IT activity is not a central requirement for eosinophil apoptosis induced by all physiologic agonists.

Figure 6.

TGF-β and Fas ligand induced eosinophil apoptosis but did not activate CoA-IT. (A) Human eosinophils cultured with TGF-β (500 pg/ml) for 0 to 96 hours were assayed by arachidonic acid transfer to radiolabeled lyso-PAF, and CoA-IT hydrolytic activity calculated as a percent of control. CoA-IT enzymatic activity (circles) was measured for times from 0 to 72 hours. Eosinophil apoptotic characteristics were also determined including phosphatidylserine exposure (open diamonds), cell volume reduction (open squares), morphologic changes (solid squares), and membrane integrity (solid diamonds) by trypan blue exclusion. Data are the average of three to eight experiments per assay. (B) Human eosinophils cultured with anti-Fas (100 ng/ml), which acts as a Fas ligand, and were measured for CoA-IT hydrolytic activity (circles) out to 72 hours. Apoptotic characteristics were also determined including phosphatidylserine exposure (open diamonds), cell volume reduction (open squares), morphologic changes (solid squares), and membrane integrity (solid diamonds) by trypan blue exclusion. Data are the average of three to nine experiments per assay.

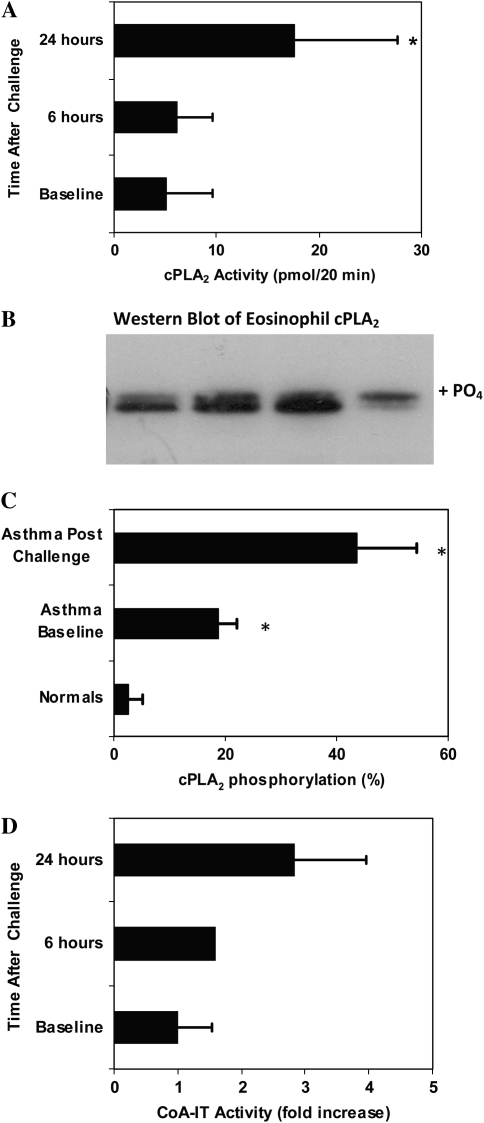

Effect of In Vivo Allergen Challenge on cPLA2 and CoA-IT

Regulation of AA and phospholipid remodeling enzymes could provide a mechanism for regulating not only eicosanoid production, but also the increased life-span of eosinophils in allergic asthma. The studies outlined above were performed in vitro. While this provides important information regarding mechanism, it does not address the important question as to whether these responses occur in vivo in a disease population. To address this question, peripheral blood eosinophils from healthy donors without asthma, and from donors with allergic asthma, before and after in vivo allergen challenge were isolated and both cPLA2 and CoA-IT activity were determined.

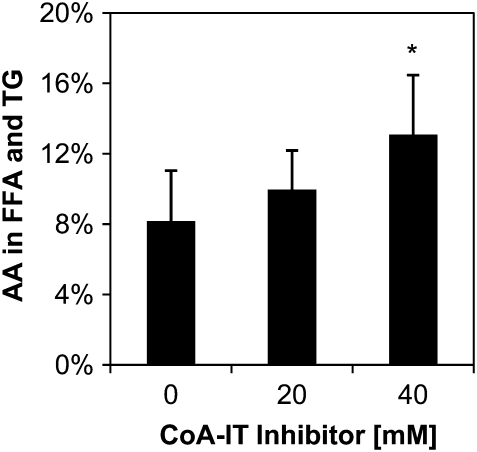

Blood eosinophils from healthy donors without asthma contained cPLA2 enzymatic activity of 8.2 ± 2.2 nmol hydrolyzed phospholipid/80 μg protein/20 minutes (n = 10). In the current study, cPLA2 enzymatic activity was measured from cytosolic fractions of eosinophils isolated from individuals with asthma before and after allergen challenge. cPLA2 enzymatic activity increased approximately 3-fold 24 hours after allergen challenge (Figure 7A), from hydrolysis of 5 ± 4 nmol phospholipid/80 μg protein/20 minutes at baseline to 18 ± 10 nmol/80 μg/20 minutes 24 hours after allergen challenge (P = 0.05, paired t test, n = 4). This increase is similar to that seen by in vitro stimulation of eosinophils with IL-5 (Figure 1) and as reported for neutrophils stimulated in vitro (19, 26). Enzymatic activity was not significantly elevated at 6 hours after challenge (6 ± 3 nmol/80 μg/20 min, P = 0.4, n = 4), nor was the baseline activity significantly lower than the nonasthmatic cPLA2 activities given above (P = 0.23, unpaired t test).

Figure 7.

Allergen challenge of patients with asthma resulted in an eosinophil cPLA2 and CoA-IT activation. Peripheral blood eosinophils were isolated from patients with asthma before and at 6 or 24 hours after allergen challenge. (A) cPLA2 enzyme activity in the eosinophil cytosolic fraction was assayed in vitro by the hydrolysis of 2-arachidonoyl-glycerophosphatidylcholine. *P < 0.05 by unpaired t test versus nonasthmatic samples. (B) cPLA2 was resolved by SDS-PAGE (50 μg/lane total protein) with Western blotting and the gel shift in cPLA2 measured by densitometry. Individual examples shown in B include subject 1 before (lane 1) and after challenge (lane 2), and subject 2 before (lane 3) and after challenge (lane 4). (C) The mean proportion (± SEM) of gel-shifted (phosphorylated) protein was significantly higher both at baseline and after allergen challenge in the subjects with asthma compared with unstimulated control subjects without asthma. *P = 0.01 by unpaired t test of samples from subjects with asthma versus those from subjects without asthma. (D) Eosinophils from patients were assayed for CoA-IT activity at baseline, and at 6 or 24 hours after allergen challenge. Fold increase is shown normalized to the unstimulated baseline for each patient (P = 0.059 for difference between baseline versus 24 h, n = 3).

Previous work by several laboratories has indicated that the activation of gIVαPLA2 is correlated with phosphorylation gel shifts, which occur in parallel to a corresponding increase in enzymatic activity assayed in vitro (19, 26–29). Gel shift assays measure gIVαPLA2 activation produced by phosphorylation of ser505 (28, 30). To corroborate the above data on gIVαPLA2 activation, Western blots were used to quantitate the phosphorylation-dependent gel shift indicative of cPLA2 activation in peripheral blood eosinophils of subjects with asthma before and after allergen challenge. Using densitometry of the Western blot (ECL) films, the amount of protein in the upper phosphorylated band (examples in Figure 7B) was quantitated relative to the lower band. On average, the proportion of gel-shifted cPLA2 was elevated in the eosinophils of patients with asthma at baseline relative to blood donors without asthma (19 ± 3% versus 3 ± 3%, mean ± SEM, P = 0.004 unpaired t test, n = 4 each) and increased further 24 hours after allergen challenge (44 ± 11%, n = 7) (Figure 7C). This increase was significant relative to blood donors without asthma (P = 0.01, unpaired t test) and nearly significant relative to the already elevated baseline values in the same patients (P = 0.06, paired t test, n = 4). Phosphorylation was apparent from the gel shifts in gIVαPLA2 samples taken 24 hours after allergen challenge. Consistent with the activation of gIVαPLA2, the total intensity was decreased in the more activated samples (Figure 7B, lane 4). This decreased intensity of cPLA2 may represent translocation to a membrane fraction or some degradation of the activated enzyme at this time point.

CoA-independent transacylase was also measured in unstimulated peripheral blood eosinophils from patients with asthma at baseline and at 24 hours after inhaled allergen challenge (Figure 7D). CoA-IT enzymatic activity increased markedly (2.8 ± 1.1-fold, P = 0.059, n = 3) in the blood eosinophils of patients with asthma 24 hours after allergen challenge. There was no significant increase in activity at 6 hours after challenge. Thus, 24 hours after inhaled allergen challenge, both gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT activities were stimulated in circulating blood eosinophils from subjects with asthma.

DISCUSSION

In allergic asthma, peripheral blood eosinophils migrate into lung tissue in response to a multistep activation process (4). This process includes IL-5–directed expansion, maturation, and survival of eosinophils from both bone marrow and blood (31). Using in vivo and in vitro models, the current study addressed the relationship between prolonged survival of eosinophils and enzymes that affect AA-phospholipid remodeling. Importantly, we found phenotypic changes in peripheral blood eosinophils within 24 hours after in vivo allergen challenge, confirming that activation of eosinophils occurred and was measurable systemically even though allergen challenge was administered directly to the lung tissue. This change in eosinophil phenotype to a primed or activated state was documented by the detection of phosphorylated gIVαPLA2 by gel shift assay. The phosphorylation of gIVαPLA2 was paralleled by activation of both cPLA2 and CoA-IT enzyme activities, measured ex vivo. Upon allergen challenge, activation of both gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT occurred to a similar magnitude. Surprisingly, activation of gIVαPLA2 was significant at baseline in this cohort of subjects with mild disease, demonstrating that these individuals can have partially activated or primed eosinophils as an altered blood phenotype during periods between obvious clinical episodes of their asthma. The increased activation of gIVαPLA2 seen at 24 hours after challenge suggests that it may contribute to the persistence of an asthmatic event after acute exposure. Primed peripheral blood eosinophils have been reported in other studies from subjects with asthma, including up-regulated surface receptors (32), up-regulated intergrins (33), primed responses to chemoattractants (34), and increased transepithelial migration (35), as well as primed superoxide gerneration (36) and leukotriene production (37). These primed features are further augmented in eosinophils in the airway fluid obtained by BAL, where activated eosinophilic cationic protein (38), lipid body formation with increased AA and eicosanoid generation (39), and hyperadhesive phenotypes (33) have been reported. The inflammatory signals responsible for the activation of asthmatic eosinophils remain to be identified, and may be either direct allergens or secondary products of allergen stimulation of airway cells. However, eosinophil priming is likely to occur during repeated passage through the pulmonary circulation in order for it to be evident in peripheral blood cells.

These in vivo observations were mimicked when isolated eosinophils were incubated with IL-5. IL-5 increased cPLA2 activity as well as CoA-IT activity and markedly enhanced the lifespan of eosinophils by delaying apoptosis. These cellular events could enhance AA-phospholipid remodeling, since augmenting gIVαPLA2 activity in the eosinophils would provide unesterified AA as a substrate for eicosanoid production, as well as generate lysophospholipid acceptors. Enhanced CoA-IT activity would increase the capacity of the cell to reacylate lysophospholipid acceptors and continue remodeling glycerolipid AA in stimulated cells. Thus, activation of these systems may contribute to delayed eosinophil apoptosis. We do not yet know if the mechanism is because both events can lower free AA levels when coupled to other metabolic enzymes, or if specific eicosanoid products contribute to delayed apoptosis (40). Evidence from T-lymphocytes suggests that gIVαPLA2 may not be directly involved in AA remodeling in glycerophospholipids (41). However, other studies suggest that gVIPLA2 (calcium-independent iPLA2) can play a critical role in AA-glycerolipid remodeling in conjunction with CoA-IT (42).

The current study also tested the hypothesis that CoA-IT activity is central to the induction of apoptosis by physiologic stimuli, such as TGF-β and Fas ligand. Exposure of eosinophils to TGF-β or anti-Fas antibody increased several markers of apoptosis, but did not influence CoA-IT activity. Thus, not all receptor agonists use this pathway of CoA-IT activation or inhibition in regulating apoptosis. Indeed, the timing of CoA-IT activation is delayed relative to gIVαPLA2 in IL-5–stimulated eosinophils, and though elevated in asthmatic blood eosinophils after allergen challenge, the increase is small. It is not yet known if activation of CoA-IT is a limited stimulated response seen in stressed cells or if constitutive activity is normally sufficient to remodel AA in primary cells. Neutrophil CoA-IT has been reported to be fully active without stimulation (15).

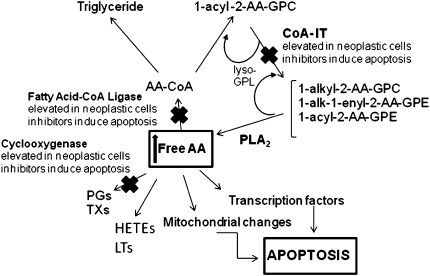

Over the past decade, inhibitors of CoA-IT have been discovered and have been shown to decrease AA-phospholipid remodeling (43). These include the specific inhibitor diethyl 7-(3,4,5-triphenyl)ureido]-4-(trifluoromethylphenoxy)-4,5-dichlorobenzene sulfonic acid (SK&F 98625) and a nonspecific inhibitor 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (Et-18-O-CH3) (17). The fact that these inhibitors can dramatically affect the viability of numerous cancer cell types implies that AA-phospholipid remodeling may play a pivotal role in the survival of certain cancers. Our laboratory has previously shown that inhibitors of AA uptake, remodeling, and metabolism induce apoptosis in SK-MES-1 cells and that this apoptosis is probably mediated by the accumulation of unesterified AA (9). Other studies have also drawn similar conclusions with regard to COX inhibition (25, 44, 45), FACL-4 (8, 9), and CoA-IT (7, 9, 42). Overexpression of COX and FACL-4 synergistically lowered free AA and inhibited apoptosis in cancer cells (8). Each of these enzymes may affect cell survival depending upon the level of cell stimulation or proliferation (41, 42). The common finding in these combined studies is the elevated level of free AA in apoptotic cells (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic of AA metabolic pathways. Disruption of AA metabolism, uptake, or remodeling by inhibitors of COX, fatty acid CoA ligase, or CoA-IT, respectively, elevates intracellular levels of AA that leads to apoptosis.

The mechanisms by which elevated free AA levels can regulate apoptosis are uncertain. One recent report suggests that AA can affect mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, with the subsequent release of cytochrome c and cell death (46, 47). We have demonstrated that eosinophil mitochondria can function as potent regulators of apoptosis (20) in part through anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (48). However, though parallels between AA and its metabolites and Bcl-2 protein balance have been observed, the mechanisms by which these molecules regulate mitochondrial function and apoptosis is complex (47). Other evidence suggests that elevated AA may stimulate ceramide-induced apoptosis via the activation of shingomyelinases, an effect that is reduced in gIVαPLA2-deficient mice (47).

We have also demonstrated that dysregulation of AA-glycerolipid remodeling induced by CoA-IT inhibitors results in marked alterations in genes critical to cell survival and apoptosis (10). Our laboratory recently provided a putative mechanism for this apoptosis by showing that elevating intracellular AA affects a number of genes that participate in cell survival and apoptosis in colon cancer cells (10). Of the 29 genes up-regulated by elevating intracellular AA, six coded for AP-1 proteins implicated in Jun dimerization and apoptotic signaling, and two more coded for the EGR-1 zinc finger transcription factor, which has been shown to physically interact with c-Jun in neuronal apoptosis. Together, these data suggest that disrupting AA-phospholipid remodeling can be a potent approach to induce cellular apoptosis.

The current study was performed to better understand whether AA remodeling enzymes impact eosinophil survival and apoptosis during allergic inflammation, where delayed apoptosis could prolong an inflammatory response. The eosinophil provides a great opportunity to examine this phenomenon, since numerous cytokines markedly increase their lifespan. IL-5 in vitro, and allergen challenge in vivo, enhanced the activity of gIVαPLA2 and CoA-IT, both of which would contribute to AA metabolism and remodeling. The current study also demonstrated that CoA-IT inhibitors both increased apoptosis in non–IL-5–treated eosinophils and prevented enhanced cell survival in IL-5–treated cells. Eosinophil AA metabolism may not be as rapid as that of tumor cells (9) or promonocytes like U937 cells (42), and thus they may be especially sensitive to changes in unesterified AA. Collectively, these data suggest that AA-phospholipid remodeling may play an important role in the survival of asthmatic eosinophils.

Current treatments of allergic eosinophilic diseases involve the use of glucocorticosteroids (49, 50). Glucocorticosteroids increase the rate of eosinophil apoptosis, although they delay the rate of apoptosis in neutrophils (48, 51). Over the last decade, induction of apoptosis has been recognized as a major therapeutic strategy for blocking tumorigenesis. This study supports the hypothesis that selective strategies, such as blocking AA-phospholipid remodeling, may induce apoptosis and help resolve acute and chronic inflammation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. David A. Bass, Emeritus Professor of Internal Medicine/Pulmonary Medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, for his invaluable contribution to this work.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL64226 (David A. Bass) and P50 AT0027820 (F.H.C.), by the General Clinical Research Center of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine (M01-RR-07122), and by a research grant from the North Carolina Chapter of the American Lung Association.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0192OC on January 16, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: D.L.B. is a consultant for Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and Spacelabs; amounts are well below $10,000 per year. F.H.C. serves on the Board of Directors of Pilot Therapeutics, Inc., and is a share holder of Pilot Therapeutics; amounts are well below $10,000 per year. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Walsh GM, Al-Rabia M, Blaylock MG, Sexton DW, Duncan CJ, Lawrie A. Control of eosinophil toxicity in the lung. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005;4:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern M, Meagher L, Savill J, Haslett C. Apoptosis in human eosinophils: programmed cell death in the eosinophil leads to phagocytosis by macrophages and is modulated by IL-5. J Immunol 1992;148:3543–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tai PC, Sun L, Spry CJ. Effects of IL-5, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-3 on the survival of human blood eosinophils in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol 1991;85:312–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wardlaw AJ. Molecular basis for selective eosinophil trafficking in asthma: a multistep paradigm. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watt AP, Schock BC, Ennis M. Neutrophils and eosinophils: clinical implications of their appearance, presence and disappearance in asthma and COPD. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005;4:415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uller L, Persson CG, Erjefalt JS. Resolution of airway disease: removal of inflammatory cells through apoptosis, egression or both? Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006;27:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trimboli AJ, Waite BM, Atsumi G, Fonteh AN, Namen AM, Clay CE, Kute TE, High KP, Willingham MC, Chilton FH. Influence of coenzyme A-independent transacylase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors on the proliferation of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 1999;59:6171–6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y, Pearman AT, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM. Intracellular unesterified arachidonic acid signals apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:11280–11285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monjazeb AM, High KP, Koumenis C, Chilton FH. Inhibitors of arachidonic acid metabolism act synergistically to signal apoptosis in neoplastic cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005;73:463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monjazeb AM, High KP, Connoy A, Hart LS, Koumenis C, Chilton FH. Arachidonic acid-induced gene expression in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2006;27:1950–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer RM, Deykin D. Arachidonoyl transacylase in human platelets. Coenzyme A-independent transfer of arachidonate from phosphatidylcholine to lysoplasmenylethanolamine. J Biol Chem 1983;258:13806–13811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarini S, Gijon MA, Folco G, Murphy RC. Effect of arachidonic acid reacylation on leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils stimulated with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. J Biol Chem 2006;281:10134–10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Triggiani M, Oriente A, Seeds MC, Bass DA, Marone G, Chilton FH. Migration of human inflammatory cells into the lung induces the remodeling of arachidonic acid into a triglyceride pool. J Exp Med 1995;182:1181–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balsinde J, Perez R, Balboa MA. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1761:1344–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker PR, Owen JS, Nixon AB, Thomas LN, Wooten R, Daniel LW, O'Flaherty JT, Wykle RL. Regulation of platelet-activating factor synthesis in human neutrophils by MAP kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002;1592:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panel V, Boelle PY, Ayala-Sanmartin J, Jouniaux AM, Hamelin R, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Flejou JF, Wendum D. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 expression in human colon adenocarcinoma is correlated with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and contributes to prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Lett 2006;243:255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chilton FH, Fonteh AN, Sung CM, Hickey DM, Torphy TJ, Mayer RJ, Marshall LA, Heravi JD, Winkler JD. Inhibitors of CoA-independent transacylase block the movement of arachidonate into 1-ether-linked phospholipids of human neutrophils. Biochemistry 1995;34:5403–5410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowton DL, Seeds MC, Fasano MB, Goldsmith B, Bass DA. Phospholipase A2 and arachidonate increase in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after inhaled antigen challenge in asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeds MC, Jones DF, Chilton FH, Bass DA. Secretory and cytosolic phospholipases A2 are activated during TNF priming of human neutrophils. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998;1389:273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peachman KK, Lyles DS, Bass DA. Mitochondria in eosinophils: functional role in apoptosis but not respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:1717–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeds MC, Nixon AB, Wykle RL, Bass DA. Differential activation of human neutrophil cytosolic phospholipase A2 and secretory phospholipase A2 during priming by 1,2-diacyl- and 1–0-alkyl-2-acyl-glycerols. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998;1394:224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 1959;37:911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi Y, Hayashi Y, Sugama Y, Miura Y, Kasahara T, Kitamura S, Torisu M, Mita S, Tominaga A, Takatsu K, et al. Highly purified murine interleukin 5 (IL-5) stimulates eosinophil function and prolongs in vitro survival. IL-5 as an eosinophil chemotactic factor. J Exp Med 1988;167:1737–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surette ME, Fonteh AN, Bernatchez C, Chilton FH. Perturbations in the control of cellular arachidonic acid levels block cell growth and induce apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Carcinogenesis 1999;20:757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler JD, Eris T, Sung CM, Chabot-Fletcher M, Mayer RJ, Surette ME, Chilton FH. Inhibitors of coenzyme A-independent transacylase induce apoptosis in human HL-60 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996;279:956–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nixon AB, Seeds MC, Bass DA, Smitherman PK, O'Flaherty JT, Daniel LW, Wykle RL. Comparison of alkylacylglycerol vs. diacylglycerol as activators of mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in human neutrophil priming. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997;1347:219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borsch-Haubold AG, Bartoli F, Asselin J, Dudler T, Kramer RM, Apitz-Castro R, Watson SP, Gelb MH. Identification of the phosphorylation sites of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in agonist-stimulated human platelets and HeLa cells. J Biol Chem 1998;273:4449–4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doerfler ME, Weiss J, Clark JD, Elsbach P. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide primes human neutrophils for enhanced release of arachidonic acid and causes phosphorylation of an 85 kD cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest 1994;93:1583–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Jacobs B, Boetticher E, Myou S, Meliton A, Sano H, Lambertino AT, Munoz NM, Leff AR. IL-5-induced integrin adhesion of human eosinophils caused by ERK1/2-mediated activation of cPLA2. J Leukoc Biol 2002;72:1046–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durstin M, Durstin S, Molski TFP, Becker EL, Sha'afi RI. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 translocates to membrane fraction in human neutrophils activated by stimuli that phosphorylate mitogen-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:3142–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster PS, Mould AW, Yang M, MacKenzie J, Mattes J, Hogan SP, Mahalingam S, McKenzie AN, Rothenberg ME, Young IG, et al. Elemental signals regulating eosinophil accumulation in the lung. Immunol Rev 2001;179:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanter D, ten Hove W, Luijk B, van Aalst C, Schweizer RC, Lammers JW, Leufkens HG, Raaijmakers JA, Bracke M, Koenderman L. Expression of activated Fc gamma RII discriminates between multiple granulocyte-priming phenotypes in peripheral blood of allergic asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson MW, Kelly EA, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, Mosher DF. Up-regulation and activation of eosinophil integrins in blood and airway after segmental lung antigen challenge. J Immunol 2008;180:7622–7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warringa RA, Mengelers HJ, Raaijmakers JA, Bruijnzeel PL, Koenderman L. Upregulation of formyl-peptide and interleukin-8-induced eosinophil chemotaxis in patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993;91:1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moser R, Fehr J, Olgiati L, Bruijnzeel PL. Migration of primed human eosinophils across cytokine-activated endothelial cell monolayers. Blood 1992;79:2937–2945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sedgwick JB, Geiger KM, Busse WW. Superoxide generation by hypodense eosinophils from patients with asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberge CJ, Laviolette M, Boulet LP, Poubelle PE. In vitro leukotriene (LT) C4 synthesis by blood eosinophils from atopic asthmatics: predominance of eosinophil subpopulations with high potency for LTC4 generation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1990;41:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venge P, Bystrom J, Carlson M, Hakansson L, Karawacjzyk M, Peterson C, Seveus L, Trulson A. Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP): molecular and biological properties and the use of ECP as a marker of eosinophil activation in disease. Clin Exp Allergy 1999;29:1172–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weller PF, Bozza PT, Yu W, Dvorak AM. Cytoplasmic lipid bodies in eosinophils: central roles in eicosanoid generation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1999;118:450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward C, Walker A, Dransfield I, Haslett C, Rossi AG. Regulation of granulocyte apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Biochem Soc Trans 2004;32:465–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boilard E, Surette ME. Anti-CD3 and concanavalin A-induced human T cell proliferation is associated with an increased rate of arachidonate-phospholipid remodeling: lack of involvement of group IV and group VI phospholipase A2 in remodeling and increased susceptibility of proliferating T cells to CoA-independent transacyclase inhibitor-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2001;276:17568–17575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez R, Matabosch X, Llebaria A, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. Blockade of arachidonic acid incorporation into phospholipids induces apoptosis in U937 promonocytic cells. J Lipid Res 2006;47:484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler JD, Fonteh AN, Sung CM, Heravi JD, Nixon AB, Chabot-Fletcher M, Griswold D, Marshall LA, Chilton FH. Effects of CoA-independent transacylase inhibitors on the production of lipid inflammatory mediators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995;274:1338–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarkar D, Nagaya T, Koga K, Nomura Y, Gruener R, Seo H. Culture in vector-averaged gravity under clinostat rotation results in apoptosis of osteoblastic ROS 17/2.8 cells. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seed MP, Freemantle CN, Alam CA, Colville-Nash PR, Brown JR, Papworth JL, Somerville KW, Willoughby DA. Apoptosis induction and inhibition of colon-26 tumour growth and angiogenesis: findings on COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors in vitro & in vivo and topical diclofenac in hyaluronan. Adv Exp Med Biol 1997;433:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pompeia C, Lima T, Curi R. Arachidonic acid cytotoxicity: can arachidonic acid be a physiological mediator of cell death? Cell Biochem Funct 2003;21:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakanishi M, Rosenberg DW. Roles of cPLA2alpha and arachidonic acid in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1761:1335–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sivertson KL, Seeds MC, Long DL, Peachman KK, Bass DA. The differential effect of dexamethasone on granulocyte apoptosis involves stabilization of Mcl-1L in neutrophils but not in eosinophils. Cell Immunol 2007;246:34–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woolley MJ, Wattie J, Ellis R, Lane CG, Stevens WH, Woolley KL, Dahlback M, O'Byrne PM. Effect of an inhaled corticosteroid on airway eosinophils and allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in dogs. J Appl Physiol 1994;77:1303–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kankaanranta H, Moilanen E, Zhang X. Pharmacological regulation of human eosinophil apoptosis. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005;4:433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallett JM, Leitch AE, Riley NA, Duffin R, Haslett C, Rossi AG. Novel pharmacological strategies for driving inflammatory cell apoptosis and enhancing the resolution of inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2008;29:250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]