Abstract

More than 100 million people in the United States live in areas that exceed current ozone air quality standards. In addition to its known pulmonary effects, environmental ozone exposures have been associated with increased hospital admissions related to cardiovascular events, but to date, no studies have elucidated the potential molecular mechanisms that may account for exposure-related vascular impacts. Because of the known pulmonary redox and immune biology stemming from ozone exposure, we hypothesized that ozone inhalation would initiate oxidant stress, mitochondrial damage, and dysfunction within the vasculature. Accordingly, these factors were quantified in mice consequent to a cyclic, intermittent pattern of ozone or filtered air control exposure. Ozone significantly modulated vascular tone regulation and increased oxidant stress and mitochondrial DNA damage (mtDNA), which was accompanied by significantly decreased vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein and indices of nitric oxide production. To examine influences on atherosclerotic lesion formation, apoE−/− mice were exposed as above, and aortic plaques were quantified. Exposure resulted in significantly increased atherogenesis compared with filtered air controls. Vascular mitochondrial damage was additionally quantified in ozone- and filtered air-exposed infant macaque monkeys. These studies revealed that ozone increased vascular mtDNA damage in nonhuman primates in a fashion consistent with known atherosclerotic lesion susceptibility in humans. Consequently, inhaled ozone, in the absence of other environmental toxicants, promotes increased vascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and atherogenesis.

Keywords: environmental oxidants, atherosclerosis, mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA damage, mice, nonhuman primates, lung, oxidative stress, nitric oxide

ozone (O3) is a ubiquitous, highly reactive gas that is a principal oxidant in photochemical smog. O3 exposure is widespread in the United States, with more than 100 million people living in areas that exceed current air quality standards (14). Extensive investigations of O3-related pathophysiological sequelae clearly document that exposures initiate and exacerbate pulmonary disease in humans, and numerous studies have suggested that inhaled O3 produces effects beyond perturbations occurring within the composite respiratory tract (14). While epidemiological studies have shown associations between O3 exposure and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (7), studies providing mechanistic links between O3 and cardiovascular dysfunction and/or disease (CVD) development remain limited.

It is well documented that other pulmonary toxicants (e.g., tobacco smoke, particulates) influence the vascular system (29). Due to the intimate coupling of the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems, and because O3 generates bioactive reaction products that lead to diverse biochemical alterations that activate immune cascades within the lung, we hypothesized that inhaled O3 initiates downstream cardiovascular perturbations. The goal of this study was to conduct a comprehensive investigation of exposure effects on vascular physiological function, endothelial-mediated vasomotor tone regulation, oxidant biochemistry, mitochondrial damage, and atherogenesis using an environmentally relevant exposure paradigm. Overall, the experimental results demonstrated that O3 exposure significantly altered blood pressure, heart rate, endothelial-dependent vascular function, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and atherogenesis in mice. Additional early life studies in nonhuman primates showed that O3 exposure increased vascular mitochondrial damage in a fashion consistent with known atherosclerotic lesion development susceptibility in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Male C57Bl/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were provided food (PicoLab Rodent Chow 20) and water ad libitum. Because normocholesterolemic C57Bl/6 mice do not typically develop atherosclerotic lesions, male apoE−/− mice were purchased (Jackson Laboratories) and fed normal mouse chow (PicoLab Rodent Chow 20) for atherosclerotic lesion assessment relative to O3 exposure; the hypercholesterolemic apoE−/− mouse is a well-characterized model for atherosclerotic lesion development (33). Animal care was given in accordance with institutional guidelines. A minimum of five animals per exposure group was used for each experimental endpoint.

Nonhuman primates.

All monkeys were from the breeding colony at the California National Primate Research Center at the University of California, Davis. Seven male infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were removed from their mothers at birth and raised as social groups in housing supplied with chemically, biologically, and radiologically filtered air, as previously described (40). Care and housing of animals before, during, and after treatment complied with the provisions of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and conformed to practices established by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by both the University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of California, Davis, Institutional Animal Use and Care Committees.

Exposure regimens.

Mouse exposures were conducted at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Environmental Exposure Facility. Commencing at 6 wk of age, C57Bl/6 mice were exposed to 0.5 ppm O3 or filtered air (FA) for 1 or 5 days, 8 h/day (12 a.m. to 8 a.m.). For atherosclerotic lesion assessment, apoE−/− mice were exposed to 0.5 ppm O3 or FA from 6 to 14 wk of age, 5 days/wk, 8 h/day (12 a.m. to 8 a.m.). This concentration is substantially lower than levels used in several previous studies (e.g., 1.0–2.5 ppm) (15, 27), and although still higher than both EPA National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) (0.075 ppm) and OSHA permissible exposure limit (0.1 ppm) regulatory levels, mice are routinely recognized as less susceptible to O3 insult than humans due to obligatory nose breathing and other intrinsic factors (42). Thus, the employed exposure paradigm represents an approach useful for delineating potential pathobiological sequelae in humans. Animals were exposed in 0.8-m3 stainless steel chambers (O3 and FA) that employed 30 vol changes/h turnover rates. Ozone was generated from medical grade O2 using a silent arc electrode and bled into the chamber inflow (∼22°C; 50% relative humidity) using mass flow controllers. Chamber supply air (O3 and FA chambers) was conditioned via passage through sequential course filter, activated charcoal, and HEPA filter units. Chamber concentrations were continuously monitored using a ThermoEnvironmental model 49 Photometric Ozone Analyzer. During exposure periods, food was removed (O3 and FA animals) to preclude ingestion of ozonation products. No differences in body weights were noted, suggesting the O3 exposure regimen did not impact food intake.

Primate exposures were conducted at the California National Primate Research Center Inhalation Exposure Facility at the University of California, Davis. Commencing at 180 days of age, three monkeys were exposed to 5 days of 0.5 ppm O3 for 8 h/day. Four age-matched control monkeys were exposed to filtered air only. Primates were exposed in large stainless steel and glass units (3.5-m3 vol) utilizing flow rates of 2.1 m3/min (30 vol changes/h). Ozone was generated from vaporized liquid medical grade oxygen by electric discharge ozonizers (46). The ozone concentration was continuously monitored with an ultraviolet ozone analyzer (model 1003; Ahm Dasibi, Glendale, CA). Because M. mulatta are nose breathers, and since all exposures occurred during limited activity/sleep (midnight to 8:00 a.m.), the inhaled doses likely did not differ appreciably from active human exposures (14).

Tissue collection.

Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection with ketamine/xylazine and exsanguinated via cardiac puncture. Tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C, except aortas used for vascular tone studies.

Primate necropsies were performed under sterile conditions with full personal protective equipment at the California Regional Primate Research Center. Under the direction of veterinarians and pathology staff, animals were euthanized using humane conditions. The aortas and hearts were removed en bloc, perfused with cold PBS buffer, and immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent analyses.

Heart rate and blood pressure measurements.

Heart rate and blood pressures (systolic and diastolic) were noninvasively measured by determining tail blood volumes with a volume pressure recording sensor and an occlusion tail-cuff (CODA System; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Animals underwent a 1-wk acclimation with mock exposures (exposed to FA only while housed in an exposure chamber) in which blood pressure and heart rates were measured daily (up to 25 measurements/animal). During this period, no differences were observed between mouse groups. Upon implementation of the actual exposure regimens, blood pressures and heart rates for FA and O3 mice were determined after an initial series of 5 acclimation measurements, followed by 20 experimental measurements, 1–2 h after completion of each exposure regimen. Mice were individually restrained in clear plastic tubes placed in trays that rested on a heating pad (30–32°C). Measurements were automatically excluded by the system when abrupt changes in blood pressure were detected.

Vascular tone.

Isometric tension was measured in murine thoracic aortas as previously described (50). Relaxation responses were reported as percent contraction relative to the maximal phenyleneprhine (PE)-induced contraction (% maximal contraction). All tension experimental permutations were tested in three to four ring segments from each animal. Results were averaged to yield a weighted mean for each animal.

Nitrite plus nitrate quantification.

Nitrite plus nitrate (NOx) levels were determined in mouse aortic tissue homogenates via quantification of the fluorescent product 1H-naphthotriazole using 2,3-diaminonaphthalene (Calbiochem no. 482655) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Oxidant stress measurements.

8-Isoprostane (8-iso PGF2α) levels were determined using the ACE competitive EIA kit (Cayman Chemicals) per the manufacturer's instructions. Activity of aconitase, an enzyme that is inactivated by superoxide (O2•−) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), was assessed as a marker suggestive of O2•− and/or ONOO− contribution to oxidant stress (20).

Superoxide dismutase activity.

Total superoxide dismutase (SOD) and mitochondrial SOD (SOD2) activities were determined in murine tissues as previously described (23).

Immunoblot analysis of SOD2, 3-nitrotyrosine, and eNOS.

Commercially available antibodies for SOD2 (Fitzgerald Industries-RDI), 3-nitrotyrosine (Biodesign), total eNOS (Cell Signaling Technology), and phospho eNOS (Ser1177 and Thr495, Cell Signaling Technology) were used to perform immunoblots on murine tissue homogenate protein. Blots were visualized using chemiluminescence of the secondary HRP-goat anti-rabbit IgG (SOD2), HRP-monoclonal mouse anti-rabbit (eNOS), or HRP-monoclonal mouse anti-goat/sheep IgG (nitrotyrosine). Blots were quantified via ECL plus Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) on a Storm 840 Imaging System (GE Healthcare). Specific activity for SOD2 was calculated by dividing SOD2 enzyme activity by the amount of SOD2 protein present as determined by immunoblot and densitometry (23).

Mitochondrial DNA damage.

Mitochondrial DNA damage (mtDNA) was evaluated by quantitative PCR (QPCR) as described previously (23). Briefly, total DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen) and quantified via the Picogreen assay kit (Invitrogen). A 16,059-bp region of the mtDNA was amplified via QPCR with [32P]dATP and isolated with agarose gel electrophoresis. To normalize samples for mitochondria count and mtDNA copy number, an 80-bp segment of mtDNA was amplified and isolated with polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gels were dried, DNA bands visualized with Storm 840 imaging system (GE Healthcare), and densitometry analysis performed using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare). Treatment damaging to mtDNA causes a decrease in amplifiable whole length mtDNA templates, which results in decreased QPCR product relative to untreated controls. Densitometry results from the 16,059-bp QPCR were normalized with those of the 80-bp QPCR and expressed as lesion frequency per 16 kb of DNA.

Studies in primates utilized similar conditions and primer sets: MM12356FOR and MM12045REV (CCACCCTTATCTCCCTAACTCTCC and CGTGTGAAGGGGGGTTTTATGTTGA, bp 12356–12379 and 12045–12021, respectively), generating a product of 16.2 kb in size. Differences in mtDNA copy number were normalized utilizing primer set MM708FOR and MM871REV (GGAGCAAGCATCAAGCACG and TAATCGTGTAACCGCGGTG, respectively) to yield a 163-bp product.

Atherosclerotic lesion assessment.

Atherosclerotic lesions were quantified by Oil red-O staining and image analysis of whole aortas, as previously described (23).

Statistical analyses.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. ANOVA was used to test the null hypothesis that all samples were drawn from a single population. If this test revealed significant differences (P < 0.05), a Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat statistical software.

RESULTS

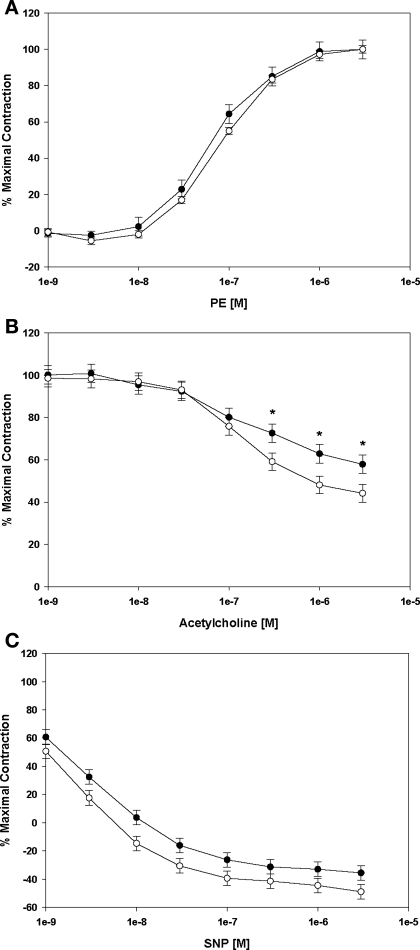

While Table 1 shows that control animal heart rates were within previously reported levels (24), O3 exposure significantly increased heart rates as well as mean blood pressures, which was largely attributable to elevated diastolic pressures. Similarly, after 5 days of O3, endothelial-dependent (acetylcholine) vasorelaxation was significantly inhibited (Fig. 1B), whereas PE-induced vasocontraction and endothelial-independent (sodium nitroprusside) vasorelaxation were not appreciably affected (Fig. 1, A and C, respectively).

Table 1.

Blood pressure and heart rates

| Systolic, mmHg | Diastolic, mmHg | Mean, mmHg | Heart Rate, beats/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filtered air (control) | 138.99±1.48 | 105.57±1.17 | 116.22±1.22 | 746.89±12.53 |

| 1 Day of Ozone | 138.29±2.25 | 102.97±1.77 | 114.41±1.78 | 798.33±24.43* |

| 5 Days of Ozone | 141.94±2.14 | 113.39±1.69*† | 122.56±1.69*† | 796.01±19.79* |

Values are means ± SE.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from filtered air controls.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from 1 day of ozone.

Fig. 1.

Differences in concentration-response curves to vasoactive agents in C57 mice exposed to either filtered air (open circles) or 5 days of 0.5 ppm O3 8 h/day (filled circles). A: phenylephrine (PE). B: acetylcholine. C: sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Relaxation was quantified as percent maximal vessel tension of the preexisting tone generated by PE. Data are means from 3–4 ring segments from each animal (n = 5 mice/group). *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. filtered air controls.

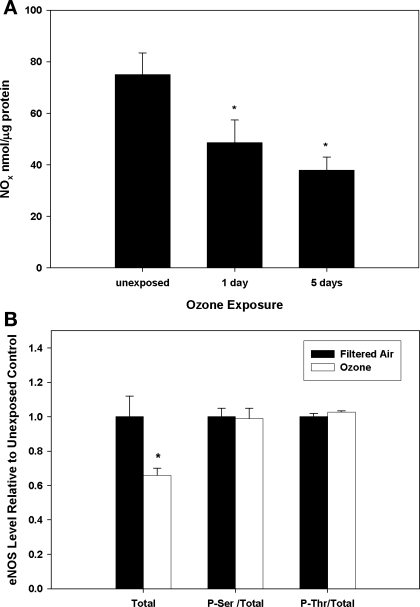

To determine whether exposure altered systemic production and/or distribution of the vasorelaxant nitric oxide (·NO), NOx levels were quantified in vascular tissues. Figure 2A shows that NOx levels were significantly decreased after both 1 and 5 days of exposure, suggesting rapid and sustained decreased bioavailability of ·NO within arterial tissues as a consequence of O3 exposure. To determine whether the diminution in vascular NOx content resulted from changes in eNOS protein, total eNOS as well as phospho-Ser1177 and phospho-Thr495 (eNOS activation and inhibition sites, respectively) eNOS levels were determined by immunoblot. Figure 2B shows that total eNOS protein was significantly decreased after exposure, whereas the ratios of phospho-Ser1177 and phospho-Thr495 to total eNOS were unchanged relative to controls, suggesting that O3 exposure potentiated a decline in total eNOS protein but did not alter the phosphorylation of Ser1177 or Thr495.

Fig. 2.

NOx (nitrite + nitrate) and eNOS protein levels in aortic tissues from control and O3-exposed mice. A: C57 mice were exposed to either filtered air (labeled as “unexposed”) or O3 (1 or 5 days); total NOx levels were determined. B: immunoblot quantification of total, phospho-Ser1177 (P-Ser), and phospho-Thr495 (P-Thr) eNOS protein levels in aortic tissues from ozone-exposed (open bars) and filtered air control (filled bars) mice. Total, total eNOS; P-Ser/Total, ratio of phospho-Ser1177 eNOS to total eNOS; P-Thr/Total, ratio of phospho-Thr495 to total eNOS. *Significant (P < 0.05) differences vs. filtered air controls.

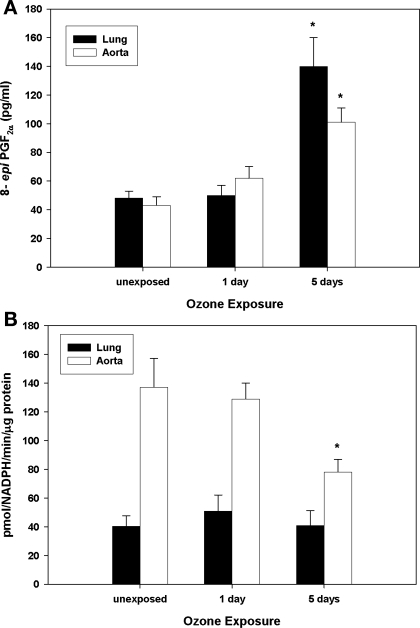

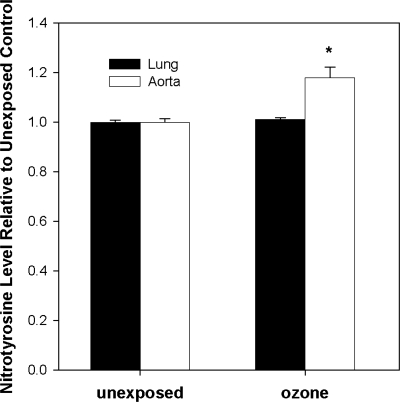

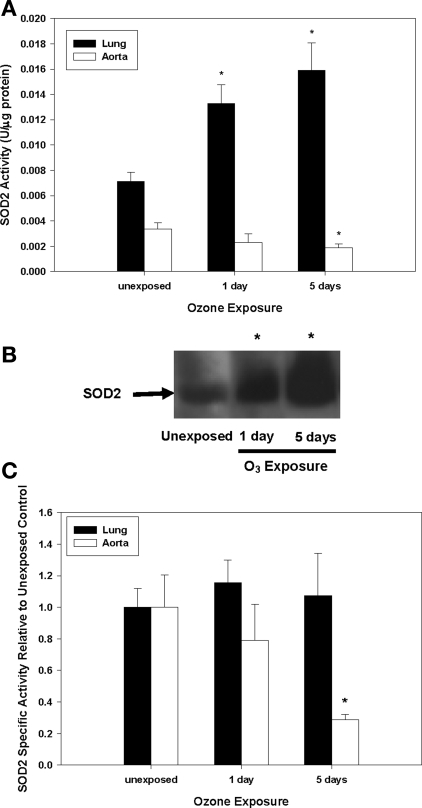

Because other stressors (e.g., environmental exposures, vascular disease) show evidence of oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and decreased mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) activity (9, 23), the effects of inhaled O3 on these parameters were investigated in both pulmonary and vascular compartments. Figure 3A illustrates that F2-isoprostane levels [isoprostanes are stable endproducts of in vivo lipid peroxidation (31)] were significantly increased in aortic tissues after 5 days of O3 exposure. Similarly, aconitase, a mitochondrial iron-sulfur enzyme that undergoes specific inactivation by O2•− and ONOO−, displayed significantly decreased activity in aortas after 5 days (Fig. 3B) of O3, suggesting that O2•− and/or ONOO− may contribute to oxidative stress within the vasculature. To further evaluate whether augmented reactive nitrogen chemistry [i.e., ONOO− generation or peroxidase activity in the presence of NO2− and H2O2 (13)] generated posttranslational protein modifications (tyrosine residue nitration), tissue 3-nitrotyrosine levels were evaluated. As illustrated in Fig. 4, O3 exposure significantly increased protein nitration as assessed in aortic homogenates. Because of the observed enhanced oxidant production and the linkages of SOD2 activity to disease pathogenesis, we quantified the effect of O3 exposure on total SOD2 activity, protein levels, and its specific activity. Figure 5A shows that SOD2 activity significantly decreased in aortas. However, despite a concomitant increase in total SOD2 protein (Fig. 5B), there was a net decline in its specific activity over the time course of exposure (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of O3 on pulmonary and vascular oxidative stress. C57 mice were exposed to filtered air (labeled as unexposed) or O3 (1 or 5 days), and isoprostane levels (A) and aconitase activities (B) were quantified in whole lung and aortic preparations. *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. filtered air controls.

Fig. 4.

3-Nitrotyrosine levels in lungs and aortas. C57 mice were exposed to filtered air (labeled as unexposed) or 5 days of O3, and nitrotyrosine levels were determined by immunoblot in lung and aortic homogenates. Nitrotyrosine levels are expressed relative to filtered air control tissue. *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. filtered air controls.

Fig. 5.

SOD2 activity and protein levels in lungs and aortas. C57 mice were exposed to filtered air (labeled as unexposed) or O3 (1 or 5 days), and SOD2 activity and protein levels were quantified in lungs (filled bars) and aortas (open bars). A: SOD2 activity. B: SOD2 immunoblot of aortic homogenates. C: SOD2 specific activity (SOD2 activity/relative SOD2 protein; determined by immunoblot). *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. filtered air controls.

Similarities and notable dissimilarities were observed in lung tissues. The above-mentioned generation of lipid autoxidation products (Fig. 3A) and SOD2 induction (Fig. 5A) were consistent with well-characterized O3 biochemistry within the lung (1, 12, 21, 22, 35, 36, 45). The enhancement in SOD2 activity appeared to be driven by increased protein expression (data not shown), with no net changes in specific activity (Fig. 5C). SOD2 induction may have compensated for any enhanced O2•− production resulting in no detectable alterations in aconitase activity (Fig. 3B) and protein nitration (Fig. 4). However, it is important to note that because O3 induces site-specific lesions in the lung, and since these analyses used whole lung homogenates, the precise species that contributed to O3-related intracellular oxidant stress within the lungs were more challenging to discern given the specifics of the sampling approach.

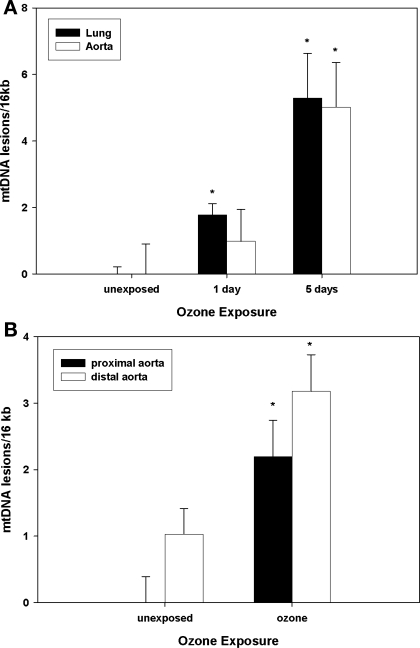

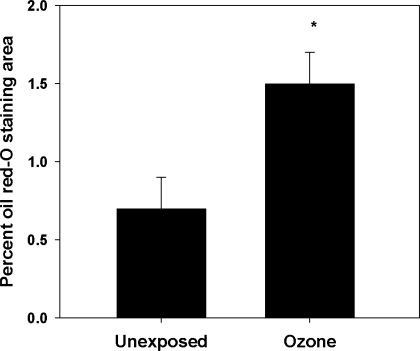

Because mtDNA can be damaged by oxidative and nitrative stress, and mitochondrial damage can further enhance cellular oxidant production, mtDNA damage was assessed in aorta and lungs from O3-exposed and control animals. Data were obtained from both the C57Bl/6 mouse model and from infant nonhuman primates exposed to a single 5-day regimen of O3. Figure 6A demonstrates that mtDNA damage accumulated in both mouse lungs and aortas over the 5-day exposure period. In the infant primate model (Fig. 6B), the abdominal region of the aorta had the greatest mtDNA damage associated with O3 exposure, a feature consistent with typical regional development of atherosclerotic lesions in primate aortas (8). Finally, to determine whether O3 exposure influenced atherosclerotic lesion formation, atherosclerotic-prone apoE−/− mice were exposed to O3, using a cyclic intermittent exposure protocol, from 6 until 14 wk of age. Figure 7 reveals that O3 exposure significantly increased aortic lesion areas compared with filtered air controls, consistent with the notion that O3 exposure influences atherogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Mitochondrial DNA damage (mtDNA) in mice and nonhuman primates. A: lung and aortic mtDNA damage in C57 mice exposed to filtered air (labeled as unexposed) or O3 (1 or 5 days). Data are expressed relative to filtered air-matched controls. B: aortic (proximal and distal) mtDNA damage in Macaca mulatta exposed to filtered air or 5 days of 0.5 ppm O3 for 8 h/day. Data are expressed relative to control proximal aortas. *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. tissue or region-matched filtered air controls.

Fig. 7.

Oil red-O staining of whole aortas. Male apoE−/− mice were exposed to filtered air or 8 cycles of O3 (1 cycle = 5 days O3 followed by 2 days of filtered air) and killed, and whole aortas were fixed and stained with oil red-O. Data are expressed as percent positive staining area relative to total aortic area. *Significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. filtered air controls.

DISCUSSION

Diverse studies suggest that pulmonary oxidative insults lead to pathophysiological outcomes that may extend beyond the lung to systemic compartments. For example, inhaled environmental toxins such as tobacco smoke or 1,3-butadiene have been shown to initiate and/or accelerate cardiovascular disease development (23, 32), and major air pollution constituents that exacerbate lung disease also exacerbate cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (2, 5, 38, 48). Numerous population studies have implied particulates as directly contributory to cardiovascular perturbations, but assigning specific causality to individual air pollutants is challenging because most ambient exposures involve complex mixtures wherein the various chemical species display differential toxicities, physicochemical interactions with the lung surface, and biological mechanisms of action. Accordingly, epidemiological studies have also associated O3 exposure with increased hospital admissions related to cardiovascular complications (39), with some showing independence of O3-related effects from other environmental factors, such as particulates (4), whereas others document that O3 in combination with particulates induces acute conduit artery vasoconstriction (6). Interestingly, a recent report suggests that exposure to isolated, concentrated ambient fine and ultrafine particles fails to induce vascular changes in CVD patients or “healthy” subjects (30). Hence, particulate exposure alone may not always mediate significant vascular effects, and thus, combinatorial influences dependent on particle composition, gaseous components (such as O3), and related physicochemical interactions among the pollutants and the lung may govern the biological impacts and outcomes of an environmental exposure.

Studies characterizing the molecular mechanisms of O3-specific vascular perturbations have been generally lacking. The increased heart rate and blood pressure measures reported herein conflict with some reports but are consistent with others (11, 17, 38, 43). The majority of previous studies assessed resting heart rates and blood pressures during or immediately after O3 exposure, whereas in this study, readouts were obtained 1–2 h postexposure in conscious mice. Hence, interstudy differences related to “time of measurement,” measurement methodology, and/or overall stress levels likely affect outcome measures. The results herein represent postexposure effects under moderate stress conditions, which may approximate population studies showing O3 impacts on acute ischemic heart disease occurring within the first 24 h after exposure (39). Finally, while various O3 or O3 plus particulates studies report no changes in blood pressure, others show that O3 increases diastolic blood pressure (43), as observed herein. Although in humans, combined O3 plus particulate exposures may modulate vascular tone (6, 43), alterations in endothelial-dependent or -independent homeostatic regulation have not been reported. Our results suggest inhaled O3, per se, initiates biological events that contribute to diminished vascular endothelial responsiveness and increased oxidant stress.

Ozone exposure decreased SOD2-specific activity and increased mtDNA damage in the murine vasculature, suggesting that inhaled O3 may perturb vascular function by increasing oxidant stress that induces mitochondrial damage leading to further oxidant production. Decreased mitochondrial SOD protein levels and activity have been associated with alterations in endothelial function, blood pressure regulation, and diminutions in eNOS protein levels (9, 37). Although it is unclear whether a direct relationship between mitochondrial oxidant production and eNOS exists, TNFα, a key inflammatory cytokine [O3 exposure induces TNFα in the lung (10) including infant primates (unpublished observations)], can decrease both eNOS and argininosuccinate synthase levels while increasing arginase levels in the vasculature (16, 18). Although the effects of TNFα on eNOS have been attributed to eNOS mRNA transcript stability (49), mitochondrial ROS production plays a pivotal role in TNFα-mediated cellular effects (19, 41, 47). It has been suggested that TNFα, eNOS, and mitochondrial biogenesis are interrelated (44). Importantly, mitochondrial function, oxidant stress, and ·NO homeostasis have all been suggested to influence atherogenesis, which could provide an explanation for the exposure-related enhancement of atherosclerotic lesion formation in the apoE−/− mouse model.

The pulmonary effects of O3 have received considerable previous attention (14). In this study, inhaled O3 increased both isoprostanes and mtDNA damage in the lung, yet NOx, 3-nitrotyrosine levels, and aconitase activities were not significantly altered. Hence, while pulmonary and vascular responses to inhaled O3 were similar in certain respects, tissue differences were also noted, although this might largely stem from the use of whole lung homogenates. Furthermore, we did not detect appreciable lung protein nitration as has been observed by others (e.g., Ref. 26). Such discrepancies may be derived from differences in exposure paradigms, sampling time, and the use of whole lung Western analyses vs. immunohistochemistry. The extent of increased pulmonary SOD2 total activity suggests appreciable induction and agrees with previous reports of increased protein levels and total SOD activity, or its isoforms (SOD1, SOD2, and SOD3), in mouse (12), rat (36), and human alveolar cells (1), although contributions from cellular repair processes cannot be discounted at the 5-day time point (inflammation would be largely resolved). Animal studies have also demonstrated that O3 induces SOD2 protein levels in proximal type II alveolar epithelial cells (45). Increased pulmonary SOD2 activity observed in these studies is consistent with augmented dismutation of O2•− to H2O2 in the lung, which is capable of contributing to both isoprostane and mtDNA damage but would reduce impacts on aconitase activity and ONOO− formation.

After dissolution into the epithelial lining fluid of the lung surface, inhaled O3 undergoes facile reaction with multiple substrates, which maintains the net driving force for absorption and produces secondary reactive species such as the ozonide radical, singlet oxygen, hydrogen peroxide, antioxidant radical intermediates, and a variety of lipid ozonation products (3, 21, 22, 25, 34, 35). Lipid ozonides are either directly cytotoxic/bioactive or can undergo decomposition reactions to generate additional bioactive species. Exposure-derived reaction products initially contact epithelial apical membranes leading to cascades that produce acute cell injury, activation of signaling pathways, and compensatory cellular responses.

Such physicochemical sequelae clearly trigger inflammatory responses that may account for systemic perturbations. For instance, cellular oxidants are key in activating the redox-sensitive transcription factor, NF-κB, which controls expression of numerous genes crucial for inflammation and stress responses, including TNFα, COX-2, and cPLA2, for example (28). Translocation of pulmonary cytokines/chemokines into the vascular space and/or activation of circulating immune cells could initiate downstream events such as observed in these current studies. Whether oxidatively modified diffusible products (e.g., lipid ozonation products) gain access to the vascular space to generate extrapulmonary outcomes remains unknown. TNFα-associated effects such as increased mitochondrial ROS production (modulated by SOD2) and decreased eNOS levels (44, 49) can influence a variety of cellular processes. The data observed herein imply that exposure-related increased O2•− production may have contributed to enhanced vascular oxidant stress and ·NO consumption, thereby impacting endothelial function. Vascular eNOS protein and NOx levels also declined, further supporting decrements in ·NO bioavailability. Thus, in composite, these results indicate that inhaled O3 disrupted normal ·NO-mediated vasoregulatory pathways. Such impacts potentially perturb endothelial function/responsiveness, oxygen delivery to the coronary circulation, and thus cardiac function. Whereas such scenarios may not immediately affect healthy individuals, changes in oxidative stress, blood pressure, and endothelial function mediated by environmental O3 exposure could potentially promote acute, clinically relevant cardiac events in persons with CVD, such as established coronary disease, or at significant risk for CVD.

These studies are the first to report direct causal linkages among inhaled O3 exposure, altered vascular function, mitochondrial damage, and atherogenesis. Importantly, initial exposure studies in infant nonhuman primates also revealed increased aortic mtDNA damage, suggesting that molecular processes characterized in the more in-depth mouse studies may be operative during early life exposures in nonhuman primates. It should be reiterated that exposures employed 0.5 ppm O3, they were conducted when primates were physically inactive, and that nasal breathing induces substantial upper airway scrubbing. Because children are routinely identified as more susceptible to air pollutants, health effect concerns beyond asthma exacerbation, for example, should be carefully considered. Future studies in both nonhuman primates and transgenic mouse models should provide important additional insights regarding the precise molecular mechanisms that mediate the vascular effects of inhaled O3, and likewise, the mechanistic links between pulmonary insult and vascular injury. Perhaps more importantly, such studies would facilitate a clearer assessment and understanding of the potential cardiovascular effects of both short- and long-term, environmentally relevant O3 exposures in adults and children.

GRANTS

Research described in this article was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants ES-11172 (S. W. Ballinger), HL-77419 (S. W. Ballinger), P01-ES-11617 (E. M. Postlethwait), HL-054696 (E. M. Postlethwait), and the Bio-Analytical Redox Biology Core (S. W. Ballinger) supported by DK-079626.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alink GM, de Boer RM, Mol J, Temmink JH. Toxic effects of ozone on human cells in vitro, exposed by gas diffusion through teflon film. Toxicology 17: 209–218, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson HR, Ponce de Leon A, Bland JM, Bower JS, Strachan DP. Air pollution and daily mortality in London: 1987–92. BMJ 312: 665–669, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballinger CA, Cueto R, Squadrito G, Coffin JF, Velsor LW, Pryor WA, Postlethwait EM. Antioxidant-mediated augmentation of ozone-induced membrane oxidation. Free Radic Biol Med 38: 515–526, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell ML, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, Dominici F. Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US urban communities, 1987–2000. JAMA 292: 2372–2378, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borja-Aburto VH, Castillejos M, Gold DR, Bierzwinski S, Loomis D. Mortality and ambient fine particles in southwest Mexico City, 1993–1995. Environ Health Perspect 106: 849–855, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook RD, Brook JR, Urch B, Vincent R, Rajagopalan S, Silverman F. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation 105: 1534–1536, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC Jr, Tager I. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation 109: 2655–2671, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock BC, Lehner ND, Clarkson TB, Feldner MA, Wagner WD, Lofland HB. Comparative primate atherosclerosis. I. Tissue cholesterol concentration and pathologic anatomy. Exp Mol Pathol 22: 151–175, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Korshunov VA, Massett MP, Yan C, Berk BC. Impaired vasorelaxation in inbred mice is associated with alterations in both nitric oxide and super oxide pathways. J Vasc Res 44: 504–512, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho HY, Morgan DL, Bauer AK, Kleeberger SR. Signal transduction pathways of tumor necrosis factor-mediated lung injury induced by ozone in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 829–839, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi JH, Xu QS, Park SY, Kim JH, Hwang SS, Lee KH, Lee HJ, Hong YC. Seasonal variation of effect of air pollution on blood pressure. J Epidemiol Community Health 61: 314–318, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubick MA, Keen CL. Tissue trace elements and lung superoxide dismutase activity in mice exposed to ozone. Toxicol Lett 17: 355–360, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eiserich JP, Hristova M, Cross CE, Jones AD, Freeman BA, Halliwell B, van der Vliet A. Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature 391: 393–397, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federal Register of March 27 2008. National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Ozone; Final Rule. EPA-HQ-OAR-2005-0172-7205 at http://www.regulations.gov. [April 19, 2009.]

- 15.Funabashi H, Shima M, Kuwaki T, Hiroshima K, Kuriyama T. Effects of repeated ozone exposure on pulmonary function and bronchial responsiveness in mice sensitized with ovalbumin. Toxicology 204: 75–83, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao X, Xu X, Belmadani S, Park Y, Tang Z, Feldman AM, Chilian WM, Zhang C. TNF-alpha contributes to endothelial dysfunction by upregulating arginase in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1269–1275, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong H, Wong R, Sarma RJ, Linn WS, Sullivan ED, Shamoo DA, Anderson KR, Prasad SB. Cardiovascular effects of ozone exposure in human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: 538–546, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin BL, Pendleton LC, Levy MM, Solomonson LP, Eichler DC. Tumor necrosis factor-α reduces argininosuccinate synthase expression and nitric oxide production in aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1115–H1121, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goossens V, Grooten J, De Vos K, Fiers W. Direct evidence for tumor necrosis factor-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen intermediates and their involvement in cytotoxicity. PNAS USA 92: 8115–8119, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausladen A, Fridovich I. Measuring nitric oxide and superoxide: rate constants for aconitase reactivity. Methods Enzymol 269: 37–41, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kafoury RM, Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Salgo MG, Zou X, Friedman M. Induction of inflammatory mediators in human airway epithelial cells by lipid ozonation products. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 1934–1942, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafoury RM, Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Salgo MG, Zou X, Friedman M. Lipid ozonation products activate phospholipases A2, C, and D. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 150: 338–349, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight-Lozano CA, Young CG, Burow DL, Hu ZY, Uyeminami D, Pinkerton KE, Ischiropoulos H, Ballinger SW. Cigarette smoke exposure and hypercholesterolemia increase mitochondrial damage in cardiovascular tissues. Circulation 105: 849–854, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojda G, Laursen JB, Ramasamy S, Kent JD, Kurz S, Burchfield J, Shesely EG, Harrison DG. Protein expression, vascular reactivity and soluble guanylate cyclase activity in mice lacking the endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase: contributions of NOS isoforms to blood pressure and heart rate control. Cardiovasc Res 42: 206–213, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langford SD, Bidani A, Postlethwait EM. Ozone-reactive absorption by pulmonary epithelial lining fluid constituents. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 132: 122–130, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laskin DL, Fakhrzadeh L, Laskin JD. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in ozone-induced lung injury. Adv Exp Med Biol 500: 183–190, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Last JA, Gohil K, Mathrani VC, Kenyon NJ. Systemic responses to inhaled ozone in mice: cachexia and down-regulation of liver xenobiotic metabolizing genes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 208: 117–126, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nature Rev 2: 725–734, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lippmann M, Frampton M, Schwartz J, Dockery D, Schlesinger R, Koutrakis P, Froines J, Nel A, Finkelstein J, Godleski J, Kaufman J, Koenig J, Larson T, Luchtel D, Liu LJ, Oberdorster G, Peters A, Sarnat J, Sioutas C, Suh H, Sullivan J, Utell M, Wichmann E, Zelikoff J. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Particulate Matter Health Effects Research Centers Program: a midcourse report of status, progress, and plans. Environ Health Perspect 111: 1074–1092, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills NL, Robinson SD, Fokkens PH, Leseman DL, Miller MR, Anderson D, Freney EJ, Heal MR, Donovan RJ, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, MacNee W, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Newby DE, Cassee FR. Exposure to concentrated ambient particles does not affect vascular function in patients with coronary heart disease. Environ Health Perspect 116: 709–715, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow JD, Harris TM, Roberts LJ 2nd. Noncyclooxygenase oxidative formation of a series of novel prostaglandins: analytical ramifications for measurement of eicosanoids. Anal Biochem 184: 1–10, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penn A, Snyder CA. 1,3 Butadiene, a vapor phase component of environmental tobacco smoke, accelerates arteriosclerotic plaque development. Circulation 93: 552–557, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setala K, Walsh A, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM, Breslow JL. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71: 343–353, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postlethwait EM, Cueto R, Velsor LW, Pryor WA. O3-induced formation of bioactive lipids: estimated surface concentrations and lining layer effects. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 274: L1006–L1016, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Friedman M. The cascade mechanism to explain ozone toxicity: the role of lipid ozonation products. Free Radic Biol Med 19: 935–941, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman I, Clerch LB, Massaro D. Rat lung antioxidant enzyme induction by ozone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 260: L412–L418, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Sepassi L, Quiroz Y, Ni Z, Wallace DC, Vaziri ND. Association of mitochondrial SOD deficiency with salt-sensitive hypertension and accelerated renal senescence. J Appl Physiol 102: 255–260, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruidavets JB, Cassadou S, Cournot M, Bataille V, Meybeck M, Ferrieres J. Increased resting heart rate with pollutants in a population based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 59: 685–693, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruidavets JB, Cournot M, Cassadou S, Giroux M, Meybeck M, Ferrieres J. Ozone air pollution is associated with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 111: 563–569, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schelegle ES, Miller LA, Gershwin LJ, Fanucchi MV, Van Winkle LS, Gerriets JE, Walby WF, Mitchell V, Tarkington BK, Wong VJ, Baker GL, Pantle LM, Joad JP, Pinkerton KE, Wu R, Evans MJ, Hyde DM, Plopper CG. Repeated episodes of ozone inhalation amplifies the effects of allergen sensitization and inhalation on airway immune and structural development in Rhesus monkeys. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 191: 74–85, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulze-Osthoff K, Beyaert R, Vandevoorde V, Haegeman G, Fiers W. Depletion of the mitochondrial electron transport abrogates the cytotoxic and gene-inductive effects of TNF. EMBO J 12: 3095–3104, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Air Quality Criteria for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants (Final). U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., EPA/600/R-05/004aF-cF, 2006.

- 43.Urch B, Silverman F, Corey P, Brook JR, Lukic KZ, Rajagopalan S, Brook RD. Acute blood pressure responses in healthy adults during controlled air pollution exposures. Environ Health Perspect 113: 1052–1055, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valerio A, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Pisconti A, Palomba L, Cantoni O, Clementi E, Moncada S, Carruba MO, Nisoli E. TNF-alpha downregulates eNOS expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in fat and muscle of obese rodents. J Clin Invest 116: 2791–2798, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weller BL, Crapo JD, Slot J, Posthuma G, Plopper CG, Pinkerton KE. Site- and cell-specific alteration of lung copper/zinc and manganese superoxide dismutases by chronic ozone exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 17: 552–560, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson DW, Plopper CG, Dungworth DL. The response of the macaque tracheobronchial epithelium to acute ozone injury. A quantitative ultrastructural and autoradiographic study. Am J Pathol 116: 193–206, 1984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong GH, Elwell JH, Oberley LW, Goeddel DV. Manganous superoxide dismutase is essential for cellular resistance to cytotoxicity of tumor necrosis factor. Cell 58: 923–931, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong TW, Lau TS, Yu TS, Neller A, Wong SL, Tam W, Pang SW. Air pollution and hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Hong Kong. Occup Environ Med 56: 679–683, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan G, You B, Chen SP, Liao JK, Sun J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha downregulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability via translation elongation factor 1-alpha 1. Circ Res 103: 591–597, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C, Patel R, Eiserich JP, Zhou F, Kelpke S, Ma W, Parks DA, Darley-Usmar V, White CR. Endothelial dysfunction is induced by proinflammatory oxidant hypochlorous acid. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1469–H1475, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]