Abstract

A previously described wheat germ protein kinase (Yan, T. F., and Tao, M. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7037–7043) was identified unambiguously as CK2 using mass spectrometry. CK2 is a ubiquitous eukaryotic protein kinase that phosphorylates a wide range of substrates. In previous studies, this wheat germ kinase was shown to phosphorylate eIF2α, eIF3c, and three large subunit (60 S) ribosomal proteins (Browning, K. S., Yan, T. F., Lauer, S. J., Aquino, L. A., Tao, M., and Ravel, J. M. (1985) Plant Physiol. 77, 370–373). To further characterize the role of CK2 in the regulation of translation initiation, Arabidopsis thaliana catalytic (α1 and α2) and regulatory (β1, β2, β3, and β4) subunits of CK2 were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. Recombinant A. thaliana CK2β subunits spontaneously dimerize and assemble into holoenzymes in the presence of either CK2α1 or CK2α2 and exhibit autophosphorylation. The purified CK2 subunits were used to characterize the properties of the individual subunits and their ability to phosphorylate various plant protein substrates. CK2 was shown to phosphorylate eIF2α, eIF2β, eIF3c, eIF4B, eIF5, and histone deacetylase 2B but did not phosphorylate eIF1, eIF1A, eIF4A, eIF4E, eIF4G, eIFiso4E, or eIFiso4G. Differential phosphorylation was exhibited by CK2 in the presence of various regulatory β-subunits. Analysis of A. thaliana mutants either lacking or overexpressing CK2 subunits showed that the amount of eIF2β protein present in extracts was affected, which suggests that CK2 phosphorylation may play a role in eIF2β stability. These results provide evidence for a potential mechanism through which the expression and/or subcellular distribution of CK2 β-subunits could participate in the regulation of the initiation of translation and other physiological processes in plants.

Protein kinase CK2 (formerly known as casein kinase II) is a ubiquitous and highly conserved serine/threonine kinase found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells (1–5). CK2 is essential for cell viability and is involved in many processes such as cell proliferation, transcriptional and translational control, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis (2). The lack of an obvious control mechanism, low co-substrate specificity (both ATP and GTP can be used as phosphate donors), and the acidophilic nature of CK2 separate it biochemically from other protein kinases (1). The pleiotropic nature of CK2 has garnered it a great deal of attention, as it has been found to phosphorylate over 300 substrates, including 60 transcription factors and over 50 proteins that regulate DNA/RNA structure and/or play a role in RNA synthesis and translation (3). For a large majority of these substrates, phosphorylation events have been observed both in vitro and in native proteins (3).

CK2 holoenzymes consist of two catalytic α-subunits that assemble with two regulatory β-subunits to form a tetrameric holoenzyme (6, 7). In mammalian cells, there is a single β-subunit isoform that forms a homodimer, onto which two catalytic subunits assemble (α/α, α′/α′, or α/α′). Yeast also possess two distinct catalytic subunits (α and α′); however, there are also two distinct isoforms of the yeast regulatory CK2β subunits (8). In yeast, both the CK2β and CK2β′ subunits are required for formation of the β-β′-dimer (9). Thus, there are three potential forms of CK2 holoenzymes in both yeast and mammalian systems. However, plants contain several isoforms for both catalytic and regulatory subunits, creating the potential for a wider variety of CK2 holoenzyme combinations that may have a role in regulating CK2 activity or substrate specificity (10).

The catalytic activity of the CK2 holoenzyme toward various substrates is generally higher than with the catalytic subunits alone (11). However, some substrates are only phosphorylated in the presence of the CK2 holoenzyme, whereas others are only phosphorylated by the catalytic α-subunit monomer (12, 13). It is not currently known if various isoforms of plant CK2β subunits confer substrate specificity; however, by regulating the levels of specific CK2β subunits plants may be able to fine-tune the phosphorylation of substrates.

A systematic study of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome recently identified four genes encoding CK2α subunits and four genes encoding CK2β subunits that exhibit diverse subcellular distribution (14). Maize shows differential expression of three CK2β subunits during development (10), and tobacco CK2 subunits are differentially expressed during the cell cycle (15). In addition to their regulated expression, CK2β subunits appear to be ubiquitinated and degraded by a proteasome-dependent pathway (16). Phosphorylation of A. thaliana CK2β4 leads to ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome pathway in a manner that is regulated by the circadian clock (17). Yeast two-hybrid data obtained from various maize CK2β subunits predicts that three CK2β isoforms are able to interact in vivo with one another (10), and at least some isoforms of recombinant maize CK2β subunits have been shown to form homodimers in vitro (10, 18). However, it is not known if this is the case for all isoforms of the plant β-subunits. Because plants possess multiple isoforms of the CK2 subunits, regulation of CK2 subunit expression/degradation and variations in the subcellular distribution of the CK2 isoforms present a potential mechanism for regulating the substrate specificity of CK2 through the formation of different CK2 holoenzyme complexes. This is the first study to clearly demonstrate the effects of different CK2β subunits on substrate specificity.

Of particular interest is the ability of various plant CK2 isoforms to phosphorylate the translational machinery of plants. The fundamental processes of translation initiation are similar in all eukaryotes; however, there are some intriguing differences that exist between plants, mammals, and yeast. Some of the most notable differences that must be considered with plant translation are the apparent absence/ambiguity of key regulators as follows: eIF4E-binding proteins and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B (19, 20). In most eukaryotic systems, these proteins control global rates of translation by regulating the formation of mRNA cap-binding complexes or eIF2 ternary complexes. However, neither of these mechanisms has been shown to function in plants to date. When one considers that both of these factors are potentially absent or have minor roles in regulation in plants, it becomes obvious some alternative mechanism(s) is likely employed for the regulation of protein synthesis during development and in response to environmental signals (19). The extensive complement of CK2 subunits seen in plants presents one potential mechanism for the regulation of the plant translational machinery.

A protein kinase isolated from wheat germ was shown to phosphorylate an unknown “target” protein (T-substrate), eIF2α, eIF3c, and three large subunit (60 S) ribosomal proteins (21–23). Although biochemical characterization of the kinase revealed casein kinase-like properties, the specific identity of the kinase was unknown. Using mass spectrometry, the study presented here unambiguously identifies the previously described protein kinase as CK2 and T-substrate as histone deacetylase 2B (HD2B).2 In this work, two of the four CK2α subunits and all four CK2β subunits from A. thaliana were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. All four recombinant A. thaliana CK2β subunits spontaneously dimerized, assembled into holoenzymes with α-subunits, and exhibited autophosphorylation in the presence of catalytic subunits. In addition, we have shown that CK2 not only phosphorylates plant eIF2α and eIF3c, but holoenzyme and monomer forms of recombinant CK2 are capable of differentially phosphorylating plant eIF2β, eIF3c, eIF4B, and eIF5. Evidence was obtained that CK2 may be involved in the protein stability of eIF2β. The results presented here suggest that CK2 may play an important role in regulating translation initiation in plants as well as other cellular processes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Purification of Wheat Germ Casein Kinase and T-substrate

Wheat germ kinase was purified from S30 (24, 25) using DEAE-cellulose (Whatman DE52) and phosphocellulose (Whatman P11) as described previously (23). The protein, eluted from the phosphocellulose column containing the peak of activity (8 ml containing 9.3 mg of protein), was concentrated to ∼1 ml using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter (Millipore). The sample was then loaded onto a 126-ml Sephacryl S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare). Three fractions containing the peak kinase activity were pooled and concentrated by centrifugal filtration to a final volume of 200 μl. The purified kinase was divided into 25-μl aliquots, quick frozen in dry ice, and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. A 48-kDa protein termed T-substrate, which was previously identified as an endogenous phosphoryl acceptor for the wheat germ kinase, was purified as described previously (21).

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

To identify the protein responsible for kinase activity, 20 μl of the concentrated sample was run on a NuPAGE 12% BisTris gel (Invitrogen) using MOPS running buffer (Invitrogen). Upon staining with Colloidal Coomassie Blue (Invitrogen), the sample was found to contain five major protein bands. Each of these bands was cut from the gel and destained using 500 μl of deionized water. Each gel slice was dehydrated with 200 μl of acetonitrile (Sigma), reduced with 10 μl of 100 mm DTT for 30 min, and alkylated with 100 μl of 100 mm iodoacetamide for 30 min. The samples were washed with 200 μl of 100 mm NH4HCO3, before repeating the dehydration process. Trypsin (0.2 μg; Promega) suspended in 20 μl of 50 mm NH4HCO3 was added to each sample and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following digestion, 40 μl of 5% formic acid in 100 mm NH4HCO3 was used to extract peptides from each sample. The purified 48-kDa protein band (T-substrate) was prepared for mass spectrometry in a similar manner.

Protein identification was performed at the Analytical Instrumentation Facility Core, University of Texas (Dr. Maria Person, Director), using a MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument (4700 Proteomics Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) as described previously (26). Briefly, each tryptic digest was dried to <5 μl in a SpeedVac (ThermoSavant), desalted with a Ziptip μ-C18 pipette tip (Millipore), and eluted with 1.5 μl of matrix onto three spots on the MALDI target. The matrix was 0.7 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Calibration Mixture 4700 (Applied Biosciences) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Spectra were acquired automatically using a 4000 Series Explorer version 3.0 RC1. Mass spectrometry (MS) spectra were obtained using 2000 laser shots over a mass range of 700–4000 and calibrated internally on trypsin autolysis peaks. The top 20 MS signals with minimum S/N 20 were selected for tandem MS fragmentation after exclusion of matrix, trypsin, and keratin peaks. GPS Explorer version 3.5 was used to perform additional peak processing and a data base search. Additional searches were performed with MASCOT version 2.0. Samples were searched against Swiss-Prot, Trembl, and EST other data bases.

Cloning and Expression of A. thaliana CK2 Subunits

For bacterial expression, appropriate primers were designed (see supplemental material) for cloning into pET23d (Novagen), such that each subunit could be expressed with a C-terminal His6 tag. Approximately 500 mg of A. thaliana flowers were ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 4 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA isolation was performed as described by the manufacturer. cDNA was made from total RNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a 25-μl reverse transcription-PCR using ∼5 μg of RNA, 40 units of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), dNTPs (0.5 mm each), 10 mm DTT, and 20 μg/ml oligo(dT). Full-length A. thaliana CK2 subunit cDNAs were amplified in a thermal cycler as follows: 10 min at 95 °C; 1 min at 94 °C; 1 min at 55 °C; 1.5 min at 72 °C for 30 cycles, followed by 10 min at 72 °C. Each 50-μl reaction contained 2.5 units of FastStart High Fidelity Enzyme Blend (Roche Applied Science), 5 μl of FastStart Reaction Buffer, 200 μm dNTP mix, 100 ng of first strand cDNA, and 10 pmol of each forward and reverse primer. PCR products from CK2 subunits α1 (At5g67380), α2 (At3g50000), β1 (At5g47080), β2 (At4g17640), β3 (At3g60250), and β4 (At2g44680) were cloned into pET23d(+) vector using NcoI/XhoI restriction sites. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (DNA Core Facility, Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Texas).

Each CK2-pET23d subunit construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli cells for expression. Overnight cultures (50 ml of LB media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin) started from a single colony were used to inoculate two times 1 liter of LB media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Invitrogen) and grown to an A600 of 0.5 at 37 °C. Expression of protein was induced with the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside to a final concentration of 0.6 mm. Following isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside induction, cells were grown for 3 h at 30 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000 × g) for 15 min at 4 °C. Each E. coli cell pellet was resuspended in 30 ml of Buffer C (50 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 600 mm KCl, 20 mm imidazole) containing 1 Complete protease inhibitor tablet (EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science). The cells were disrupted by sonication three times for 30 s at 70% power and two times for 30 s at 90% power using a Vibra Cell sonicator (Sonics & Materials Inc.). Lysed cells were centrifuged at 184,048 × g for 30 min at 4 °C.

Purification of His6-tagged Proteins

Purification of His6-tagged proteins was similar to previously described methods with the following modifications (27). His6-tagged proteins were eluted from Ni-NTA with Buffer D (20 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 250 mm imidazole) containing 300 mm KCl for CK2α or 100 mm KCl for CK2β subunits. Fractions containing the highest amount of protein were immediately applied to a 1-ml phosphocellulose column (Whatman P11) equilibrated in either Buffer B-300 or Buffer B-100 (20 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 10% glycerol, and KCl as indicated, where Buffer B-100 is Buffer B containing 100 mm KCl) for CK2α and CK2β subunits, respectively. CK2α subunits were then eluted with a 10× gradient (10 ml) of Buffer B containing 0.3–1 m KCl. CK2β subunits were eluted with a 10× gradient (10 ml) of Buffer B containing 0.1–0.5 m KCl. All fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those containing the highest purity and concentration of protein were pooled. CK2α fractions were dialyzed overnight at 4 °C in Buffer B-100. CK2β subunits were not dialyzed as this resulted in a significant loss of protein, presumably by binding of the protein to the dialysis tubing.

Reconstitution of CK2 Holoenzymes in Vitro

CK2 subunits or holoenzymes (300 μg) were applied to an FPLC HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column (126 ml bed volume; GE Healthcare) or FPLC HiLoad 16/60 Superdex S200 column (126 ml bed volume; GE Healthcare) equilibrated in Buffer B-180, and the elution was monitored by A280 for 120 ml. To analyze holoenzyme formation using gel filtration, CK2α and CK2β subunits were combined in a 1:1 molar ratio (∼164 μg of CK2α and ∼135 μg of CK2β), and the KCl concentration was adjusted to 180 mm using Buffer B and incubated on ice for 1 h prior to application to the column.

To analyze the phosphorylation of initiation factors by CK2 holoenzymes, eight holoenzyme complexes were formed (CK2α1β1, CK2α1β2, CK2α1β3, CK2α1β4, CK2α2β1, CK2α2β2, CK2α2β3, and CK2α2β4). For each reaction, 50 pmol of either CK2α1 or CK2α2 was combined with 50 pmol of CK2β1, -β2, -β3, or -β4 in Buffer B-50 and incubated on ice for 1 h. To verify complex formation, 25 μl of each reaction was run on a 4–20% Tris-glycine nondenaturing gel (Invitrogen) at 4 °C. Each of these holoenzyme preparations was used to evaluate the activity toward various substrates. Similar holoenzyme formation was performed in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (∼100 cpm/pmol) to evaluate the autophosphorylation of CK2β subunits. CK2 holoenzyme combinations were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, gels were stained with a SilverSNAP kit (Pierce), dried, exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare) overnight, and images analyzed using Molecular Imager FX and Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad).

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of CK2 Substrates

To obtain nonphosphorylated substrates, plant initiation factors and HD2B (T-substrate) were cloned and expressed in E. coli as described below for each factor. The coding region for each target was amplified, cloned into a pET vector (Novagen) for bacterial expression, and purified using either phosphocellulose or a Ni-NTA matrix. Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (DNA Core Facility, Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Texas). Sequences of primers used are shown in the supplemental material.

eIF2

Wheat eIF2α was previously cloned into pET30a(+) for bacterial expression (28). The eIF2α coding region was amplified from this construct and cloned into the NdeI/BamHI site of pET15b(+). This new His-eIF2α construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and expressed and purified as described above for CK2β subunits. A. thaliana His-eIF2α (At5g05470) was amplified from A. thaliana cDNA and cloned into pET23d(+) for expression with a C-terminal His6 tag. This construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli, and A. thaliana His-eIF2α was expressed and purified as described previously for wheat His-eIF2α. Wheat eIF2β was prepared as described previously (29). Recombinant A. thaliana wild-type eIF2β (At5g20920) was amplified from expressed sequence tag TO4524 and cloned into pET23a(+) using NcoI/SalI restriction sites. This construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli expression cells and purified as described previously for wheat eIF2β (29).

eIF3c

The cDNA for wheat eIF3c was amplified from expressed sequence tag BJ257961 and cloned into pET23d (+). This construct adds a C-terminal His6 tag when using the NcoI/XhoI site. The plasmid was transformed into Arctic Express DE3(RIL) E. coli cells (Stratagene) and expressed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were harvested, and His-eIF3c was purified as described previously for CK2β subunits.

eIF4B

The cloning, expression, and purification of wheat eIF4B has been described previously (27). The cloning, expression, and purification of A. thaliana eIF4B1 and eIF4B2 are described by Mayberry et al.3

eIF5

The cloning and expression of wheat eIF5 have been described previously (27). The coding region of A. thaliana eIF5 (At1g77840) was amplified from cDNA and cloned into pET15b(+) using NcoI/BamHI restriction sites. This construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and expressed as described previously for wheat eIF5. The cell extract was diluted with Buffer B to 150 mm KCl and loaded onto a 2-ml phosphocellulose column equilibrated in Buffer B-150. Recombinant A. thaliana eIF5 was eluted from the column using a 5× gradient (10 ml) from 150 to 500 mm KCl in Buffer B, and 10 μl of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE to evaluate the purity of the eluted eIF5. Peak eIF5 fractions were pooled and dialyzed in Buffer B-80. The sample was then loaded onto a 1-ml High Trap Q FF column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in Buffer B-80. The protein was eluted with a 10× gradient (10 ml) of 80–350 mm KCl in Buffer B, and each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE to evaluate the purity. Fractions were stored at −80 °C.

T-substrate/HD2B

Primers were designed for cloning A. thaliana HD2B cDNA (At5g22650) into the pET23d(+) expression vector with a C-terminal His6 tag using NcoI/XhoI restriction sites as described above. The His-HD2B construct was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and expressed and purified as described above for CK2β subunits.

Phosphorylation of CK2 Substrates

For translation initiation factor phosphorylation, a kinase assay was conducted using 10–50 pmol of purified translation initiation factor as substrate. Generally, 20 μl-incubation mixtures contained 50 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 5 mm MgCl2, 2.4 mm DTT, 0.2 mm [γ-32P]ATP (∼100–250 cpm/pmol), 100–150 mm KCl, and ∼1 pmol of CK2. Incubation was at 30 °C for 20 min or as indicated. Each reaction was terminated by the addition of 4× SDS loading dye (2.5 m Tris, pH 6.8, 40% glycerol, 8% SDS, 0.1% bromphenol blue). Samples were heated at 100 °C for 5 min and separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, gels were dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences).

To compare the activity of the various forms of recombinant CK2, ∼1 μg of each substrate was incubated with 0.5 pmol of CK2α (monomer) or 0.25 pmol of holoenzyme (tetramer) at 25 °C for 15 min. Each reaction was treated as described previously and visualized by phosphorimaging. Quantitative densitometry was performed using Quantity One (Bio-Rad), and results were expressed as counts/mm2. Each reaction was performed in triplicate for the 10 recombinant CK2 kinase forms (CK2α1 only, CK2α2 only, CK2α1β1, CK2α1β2, CK2α1β3, CK2α1β4, CK2α2β1, CK2α2β2, CK2α2β3, and CK2α2β4).

To quantify the number of phosphorylation sites present in each substrate, the phosphorylation reaction (50 μl) contained 50 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 5 mm MgCl2, 2.4 mm DTT, 0.2 mm [γ-32P]ATP (∼100 cpm/pmol), and 100 mm KCl, 10 μg of substrate, 5 pmol of recombinant CK2α1, and an additional 5 μg of acetylated bovine serum albumin. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 5, 15, or 30 min, stopped by the addition of 1 ml of HMK buffer (20 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 2.5 mm MgCl2, and 100 mm KCl), and immediately passed through a nitrocellulose filter (Microfiltration Systems, 0.45 μm) that had been pre-soaked in 1 mm KPO4, pH 6.8. Each filter was washed with ∼2 ml of cold HMK buffer, dried, and analyzed using a scintillation counter. Reactions were performed in triplicate. Each value was corrected for the amount of [γ-32P]ATP retained by the filter in the absence of substrate. CK2β appears to be a requisite for phosphorylation of eIF2β; therefore, the CK2α1β4 holoenzyme was used in place of CK2α1 alone for its phosphorylation. For this reaction, a CK2α1β4 blank was run to control for autophosphorylation of the CK2β subunit.

Western Analysis

Transgenic A. thaliana lines overexpressing CK2β3 (30) or CK2β4 (17) were kindly provided by Dr. Elaine Tobin (UCLA) and Dr. Paloma Mas (Consorcio Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentàries, Barcelona, Spain) respectively. T-DNA insertion lines for CK2α1, CK2α2, and CK2α3 were generously provided by Dr. Q. Bu (University of Texas, Austin). A. thaliana protein extracts were prepared from seedlings (2 weeks) grown on MS-plates under sterile conditions (16 h days) and prepared by homogenizing seedlings in liquid nitrogen followed by resuspension in 250 μl of 50 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, containing 1 Complete protease inhibitor tablet (EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science) per 50 ml of buffer. 4× SDS loading dye was added to 15 μg of each extract, separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride. Blots were blocked with HNAT (10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Tween 20) containing 5% dry milk. Primary antibodies used were rabbit antiserum to recombinant wheat eIF2β, eIF2α, eIF3c, eIF4B, or eIF5 (27) or mouse monoclonal α-tubulin antibodies (037K4829, Sigma). Blots were incubated with a 1:3000 dilution of primary antibody in HNAT/milk for 12 h at 4 °C followed by extensive washes with HNAT/milk solution. The second antibody was a 1:20,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase or goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) in HNAT/milk and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Following extensive washes with HNAT (>4), antibody reactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce) and exposure to film.

RESULTS

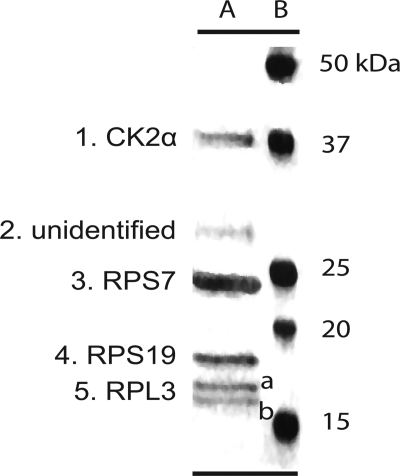

Purification of Native CK2

The wheat germ kinase previously shown to phosphorylate eIF3c, eIF2α, and three large subunit (60 S) ribosomal proteins (22) was identified as CK2α (casein kinase IIα; BAB59136) using mass spectrometry. The CK2α purified from wheat germ (Fig. 1, band 1) eluted from Sephacryl S-200 HR at ∼37 kDa. Several other proteins co-purified with wheat CK2α were identified as 60 S ribosomal protein S7 (28 kDa, band 3), 40 S ribosomal protein S19 (19 kDa, band 4), two isoforms of 60 S ribosomal protein L3 (16/17 kDa, bands 5a/5b), and one band that could not be identified (band 2). Previously we had shown that wheat germ 80 S ribosomes have CK2 activity associated with them even after high salt treatment, suggesting a strong association of CK2 with ribosomes (22). Recently an extensive analysis identified interacting partners of mammalian 40 S ribosomal protein S19 (RPS19) (31). Mammalian RPS19 was found to interact with mammalian orthologs (60 S ribosomal protein L3, 60 S ribosomal protein S7, and CK2α) of three of the plant proteins identified in this work by mass spectrometry of the purified wheat germ CK2 preparation. The observations in this work support the mammalian data that suggest CK2α may bind to ribosomes to phosphorylate various ribosomal proteins, initiation factors, or other associated proteins of the translational machinery (32). There is some speculation that CK2 phosphorylation could also regulate ribosome assembly or the degradation of specific ribosomal proteins (33–35).

FIGURE 1.

Native wheat germ kinase preparation. The purified protein preparation (lane A) containing native wheat CK2 was resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel and silver-stained (Pierce). Bio-Rad Precision Plus molecular weight markers are as indicated (lane B). In separate experiments, the protein bands were identified by mass spectrometry as follows: band 1, CK2α subunit; band 2, unidentified protein; band 3, 40 S ribosomal protein S7 (RPS7); band 4, 40 S ribosomal protein S19 (RPS19); bands 5, a and b, isoforms of 60 S ribosomal protein L3 (RPL3).

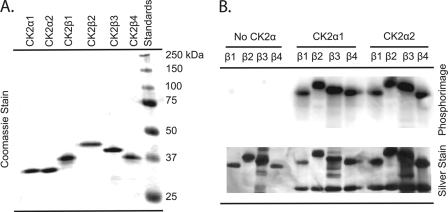

Expression and Purification of A. thaliana CK2 Subunits

cDNAs for two of the four catalytic subunits (CK2α1 and CK2α2) and all four regulatory A. thaliana CK2β subunits were obtained by reverse transcription of mRNA and cloned into pET23d(+) with a His6 tag. Attempts to obtain CK2α3 (At2g23080) cDNA from A. thaliana flowers were not successful, as all products were identified as either CK2α1 or CK2α2 cDNA. This is consistent with the high degree of similarity in these sequences and previous findings that CK2α3 expression is significantly lower when compared with other α-subunits (14). CK2αcp (At2g23070) was not pursued because of its chloroplast-specific nature. A single variation was detected in the cDNA for CK2β4, where an alanine insertion occurred after amino acid residue 240 because of the inclusion of the first three nucleotides (GCA) after the predicted splicing site of the fourth intron. Approximately half of all expressed sequence tags in GenBankTM contain this variation, suggesting alternate splicing at this site.

A high amount of soluble CK2 protein was obtained for all six subunits (2–10 mg) following purification on Ni-NTA resin; however, a small amount of contaminating protein was present in the imidazole eluant. Protein preparations were further purified, and the imidazole was removed by chromatography on phosphocellulose. All six recombinant A. thaliana CK2 subunits (α1, α2, β1, β2, β3, and β4) were purified to near homogeneity (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis and autophosphorylation of A. thaliana CK2 subunits. A, purified recombinant A. thaliana CK2 subunits were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Each lane contains 1.5 μg of the following: lane 1, CK2α1; lane 2, CK2α2; lane 3, CK2β1; lane 4, CK2β2; lane 5, CK2β3; lane 6, CK2β4; lane 7, molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) are as indicated. B, reactions (100 μl) contained 50 pmol of β-subunit (CK2β1, CK2β2, CK2β3, or CK2β4) and were incubated in the presence or absence of either CK2α1 or CK2α2 (50 pmol) and [γ-32P]ATP (∼100–250 cpm/pmol). Reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gel) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The gel was silver-stained, dried, and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Each lane contains ∼5 pmol of holoenzyme complex (10 μl of the reaction mixture). Lane 1, CK2β1; lane 2, CK2β2; lane 3, CK2β3; lane 4, CK2β4; lane 5, CK2α1β1; lane 6, CK2α1β2; lane 7, CK2α1β3; lane 8, CK2α1β4; lane 9, CK2α2β1; lane 10, CK2α2β2; lane 11, CK2α2β3; lane 12, CK2α2β4.

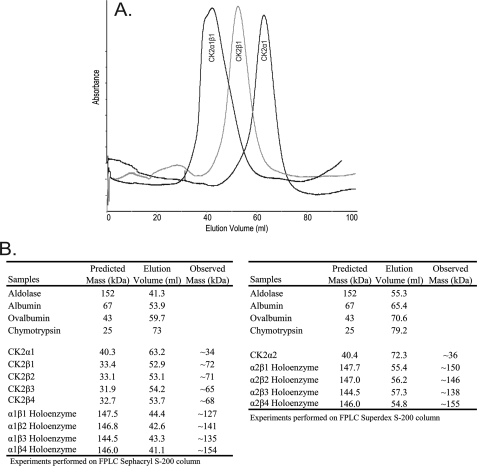

Formation of Tetrameric Holoenzyme Complexes

Previous studies have demonstrated that CK2 holoenzyme formation precedes β-subunit autophosphorylation (36). All combinations of recombinant A. thaliana holoenzymes exhibit autophosphorylation of the CK2β subunits when incubated with either CK2α1 or CK2α2 (Fig. 2B). In the formation of all eight holoenzyme complexes, only the CK2β subunits underwent autophosphorylation, as CK2α1 and CK2α2 subunits seen in the silver-stained gel were not observed in the phosphorimage (Fig. 2B). The ability of recombinant A. thaliana protein kinase subunits CK2α1, CK2α2, CK2β1, CK2β2, CK2β3, or CK2β4 to form tetrameric holoenzyme complexes in vitro was evaluated by FPLC gel filtration as shown in Fig. 3. CK2α1 (40 kDa) eluted between ovalbumin (59.7 ml, 43 kDa) and chymotrypsin (73 ml, 25 kDa) as expected (Fig. 3). CK2β subunits elute corresponding to a molecular mass of ∼70 kDa. This suggests that the recombinant plant CK2β subunits spontaneously form homodimers in vitro, because the predicted molecular mass of the monomeric subunit is 32–33 kDa (Fig. 3). When combined in a 1:1 molar ratio, the CK2α1 and CK2β1 subunit elution profiles shift to a single higher molecular weight peak (Fig. 3A). The peak of this CK2 holoenzyme product elutes after aldolase (152 kDa), suggesting a molecular mass of ∼127 kDa. The predicted molecular mass of the tetrameric holoenzyme, which consists of a CK2β1 dimer and two CK2α1 subunits, is 147.5 kDa. Similar results were obtained with all four CK2β regulatory subunits when combined with CK2α1 or CK2α2 (Fig. 3B). Based on the elution profiles, it appears that all four A. thaliana CK2β subunits form homodimers, which are capable of assembling into holoenzymes in the presence of either CK2α1 or CK2α2.

FIGURE 3.

FPLC gel filtration of CK2 subunits and holoenzymes. Individual recombinant A. thaliana CK2 subunits (300 μg), CK2 holoenzymes (300 μg), and a series of standards (300 μg) were applied to an FPLC HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column (126-ml bed volume; GE Healthcare) or FPLC HiLoad 16/60 Superdex S200 column (126-ml bed volume; GE Healthcare) in Buffer B-180, and the elution was monitored by A280 for 120 ml. Holoenzymes were formed by incubating CK2 subunits at a 1:1 molar ratio on ice for 1 h. A, representative elution pattern for individual subunits CK2α1, CKβ1, and holoenzyme CK2α1β1 on the HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column is shown. B, summary of elution volumes from gel filtration.

Further support of holoenzyme formation was obtained by running a native gradient gel with the eight possible CK2 holoenzyme tetramers. Each holoenzyme migrated through the gel as a distinct high molecular weight band consistent with formation of a holoenzyme (data not shown). These results taken together demonstrate that all four isoforms of recombinant A. thaliana CK2β are capable of forming functional holoenzyme complexes with either CK2α1 or CK2α2 in vitro.

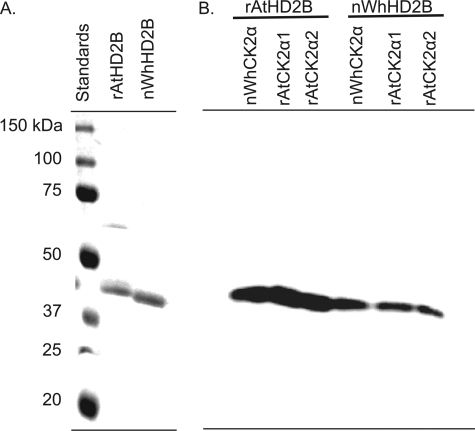

Catalytic Activity of Recombinant A. thaliana CK2 Subunits

It has been previously demonstrated that wheat germ kinase, identified in this study as CK2α, phosphorylates an endogenous wheat germ protein termed T-substrate (23). We identified T-substrate in this study as HD2B. To confirm the activities of native wheat CK2 and recombinant A. thaliana CK2 were similar, A. thaliana HD2B cDNA was cloned, expressed, and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 4A). Both native wheat HD2B (T-substrate) and recombinant A. thaliana HD2B were phosphorylated by A. thaliana CK2 catalytic subunits and endogenous wheat germ CK2 in vitro (Fig. 4B). However, the native wheat substrate appears to be somewhat less phosphorylated than the recombinant AtHD2B. This may be due to partial phosphorylation of the native wheat preparation or a difference in the number of phosphorylation sites between wheat and A. thaliana HD2B. Both wheat and A thaliana HD2B contain numerous predicted CK2 phosphorylation sites (Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

SDS-PAGE analysis and phosphorylation of HD2B by native and recombinant CK2. A, native wheat HD2B (T-substrate) and recombinant A. thaliana HD2B were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel, and the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. 1st lane, precision protein standards (Bio-Rad) as indicated; 2nd lane, 2 μg of recombinant A. thaliana HD2B (rAtHD2B); 3rd lane, 2 μg of native wheat HD2B/T-substrate (nWhHD2B). B, reactions (20 μl) were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C and separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Native wheat germ CK2 preparation (nWhCK2α, 1 pmol, 1st and 4th lanes), recombinant A. thaliana CK2α1 (rAtCK2α1, 1 pmol, 2nd and 5th lanes), and recombinant A. thaliana CK2α2 (rAtCK2α2, 1 pmol, 3rd and 6th lanes) were incubated with nWhHD2B (40 pmol) or rAtHD2B (40 pmol).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of in vitro and in silico CK2 phosphorylation site predictions

The number of in vitro CK2 phosphorylation sites in each initiation factor substrate was estimated by the incorporation of [32P] into polypeptide as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results obtained in vitro are expressed as the average of three experiments ± S.D.

| Factor | No. of CK2 phosphorylation sites |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro |

In silico predictions |

||||||

| Scansitea | NetPhosKb | KinasePhosc | |||||

| rWheIF2α | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| rAteIF2α | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| rWheIF2β | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| rAteIF2β | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| rWheIF3c | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 15 |

| rAteIF3c | NDd | 7 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 8 |

| rWheIF4B | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| rAteIF4B1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| rAteIF4B2 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 12 |

| rWheIF5 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| rAteIF5 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| rWhHD2B | ND | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 14 |

| rAtHD2B | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 9 |

| <0.5e | <0.59e | >0.60e | >0.57e | 100%e | 95%e | ||

a ScanSite version 2.0 is available on line.

b NetPhosK version 1.0 is available on line.

c KinasePhos is available on line.

d ND means not determined.

e Phosphorylation sites were predicted using two cutoff values for each program.

Phosphorylation of Plant Initiation Factors by CK2

A survey for CK2 substrates in addition to eIF2α and eIF3c was conducted with plant initiation factors. Predictions in silico (Table 1) suggest that several initiation factors contain multiple consensus CK2 phosphorylation sites. Using expressed recombinant A. thaliana CK2, it was shown that A. thaliana eIF2α, eIF2β, eIF4B1, eIF4B2, and eIF5 (Fig. 5A) as well as recombinant wheat eIF2α, eIF2β, eIF3c, eIF4B, and eIF5 (Fig. 5B) are genuine substrates for CK2. Consistent with the in silico program prediction of low confidence sites, CK2 did not phosphorylate recombinant wheat eIF1, eIF1A, eIF4E, eIF4G, eIFiso4E, eIFiso4G, or eIF4A in vitro (results not shown). The presence of multiple subunits of CK2α and CK2β suggests that there might be differential activity of CK2 forms toward substrates. Each CK2 holoenzyme and individual CK2α subunit was tested for activity against initiation factor substrates.

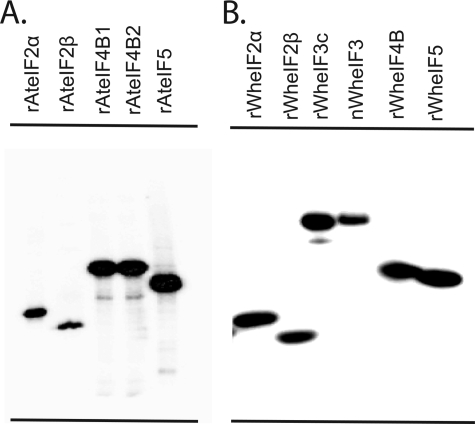

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylation of plant eIF2, eIF3, eIF4B, and eIF5 by CK2. The phosphorylation reactions (20 μl) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging. A, 1st lane, recombinant A. thaliana eIF2α (25 pmol), recombinant A. thaliana eIF2β (25 pmol), recombinant A. thaliana eIF4B1(15 pmol), recombinant A. thaliana eIF4B2 (15 pmol), and recombinant A. thaliana eIF5 (20 pmol). B, 1st lane, recombinant wheat eIF2α (50 pmol); 2nd lane, recombinant wheat eIF2β (50 pmol); 3rd lane, recombinant wheat eIF3c (25 pmol); 4th lane, native eIF3 (10 pmol); 5th lane, recombinant eIF4B (15 pmol); 6th lane, recombinant eIF5 (15 pmol). To optimize CK2 phosphorylation, wheat and A. thaliana eIF2α, eIF3c, eIF3, and eIF5 as well as wheat eIF4B were phosphorylated by ∼1 pmol of recombinant A. thaliana CK2α1; wheat and A. thaliana eIF2β (2nd lane) and recombinant A. thaliana eIF4B1 or eIF4B2 were phosphorylated by ∼0.25 pmol of the CK2α1β1 holoenzyme.

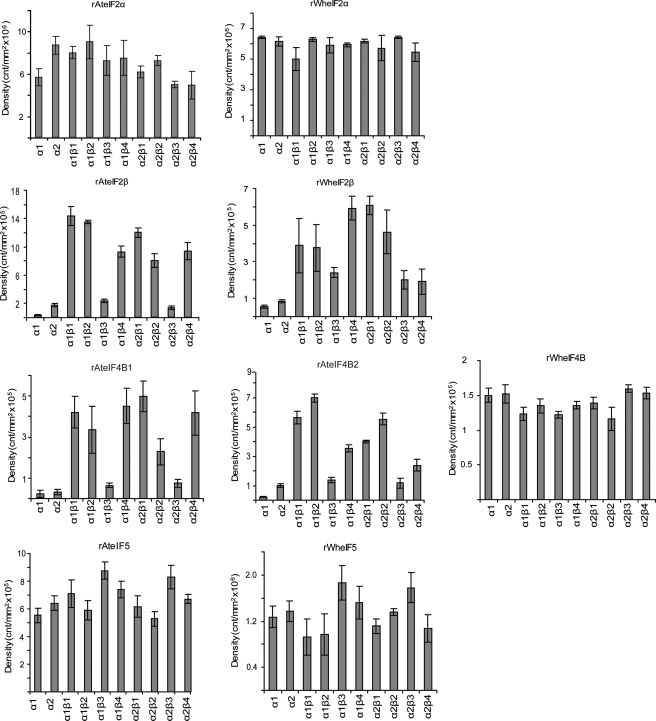

eIF2α

CK2β subunits were found to slightly increase phosphorylation of A. thaliana eIF2α by CK2α1 (1.3–1.6 times) and modestly decrease phosphorylation by CK2α2 (0.6–0.8 times; Fig. 6). In contrast, CK2α subunits alone and the various holoenzymes showed no significant difference in phosphorylation for wheat eIF2α (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Phosphorylation of plant initiation factors by CK2α or CK2 holoenzymes. Plant initiation factors were incubated with CK2α or CK2 holoenzyme as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each reaction was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel. The gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging to quantify incorporation of 32P into the substrate. Units are arbitrary and are expressed as counts/mm2. Each reaction was performed in triplicate and averaged. Error bars represent standard deviation. Note that scales for the y axis vary. Amounts of protein loaded on the gel are as follows: rAteIF2α (25 pmol), rAteIF2β (25 pmol), rAteIF4B1(15 pmol), rAteIF4B2 (15 pmol), rAteIF5 (20 pmol), rWheIF2α (25 pmol), rWheIF2β (25 pmol), rWheIF4B (25 pmol), rWheIF5 (25 pmol).

eIF2β

The phosphorylation of both A. thaliana and wheat eIF2β by CK2α is negligible in the absence of CK2β subunits. The phosphorylation of AteIF2β is increased by holoenzyme formation (∼2.5–20 times; Fig. 6). Formation of holoenzymes with CK2β3 results in a modest increase in phosphorylation (∼2.5–3 times), whereas CK2β1 and CK2β4 result in a much greater increase (∼14–20 times). Similar to AteIF2β, the phosphorylation of wheat eIF2β increases by ∼4–11 times in the presence of various CK2β subunits (Fig. 6). This increase is greatest in the presence of CK2α1β4 and CK2α2β4. Together these results may indicate a differential effect of the various CK2β subunits on the activity of the CK2α catalytic subunit isoforms toward a protein substrate.

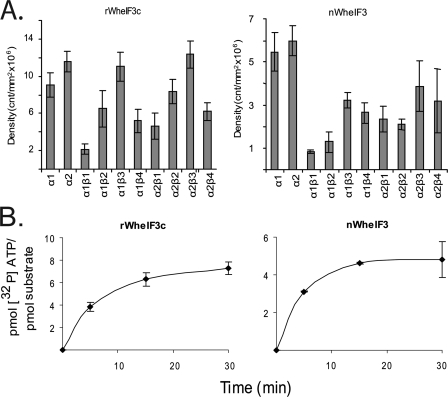

eIF3

The presence of CK2β subunits variably reduces the phosphorylation of both native and recombinant wheat eIF3c by CK2α subunits (Fig. 7A). Native wheat eIF3 contains 13 nonidentical subunits, and only eIF3c is a substrate for CK2. The reduction in recombinant wheat eIF3c phosphorylation is most dramatic in the case of CK2α1 holoenzyme formation with CK2β1, which results in an ∼7 times drop in activity. Similar results for native eIF3c are seen with other CK2 subunits, as holoenzyme formation reduced activity of the catalytic subunits by ∼1.5–7 times. Because eIF3c has multiple phosphorylation sites (Table 1), it is possible that various CK2β subunits have specificity for certain sites. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of native wheat germ eIF3c, which is in complex with 12 other eIF3 subunits, shows a more dramatic reduction in phosphorylation in the presence of CK2β subunits than recombinant eIF3c (Fig. 7A). This presents the possibility that some sites may already be phosphorylated in native eIF3c, and other eIF3 subunits may prevent access to certain sites, or there are significant conformational differences between eIF3c in complex and “free” eIF3c. A. thaliana eIF3c has yet to be cloned; however, based on the results from wheat eIF3c it is also likely to be a substrate for CK2 and has 2–12 predicted CK2 sites (Table 1). In addition, the Arabidopsis Protein Phosphorylation Site data base (PhosPhAt 2.1) contains spectra identifying the in vivo phosphorylation of a consensus CK2 site (Ser-40) in the N terminus of A. thaliana eIF3c (37).

FIGURE 7.

Phosphorylation and quantitative phosphorylation of wheat eIF3c. A, recombinant WheIF3c (15 pmol) or native WheIF3 (5 pmol) was incubated with CK2α or CK2 holoenzyme as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each reaction was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel. The gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging to quantify incorporation of 32P into the substrate. Units are arbitrary and are expressed as counts/mm2. Each reaction was performed in triplicate and averaged. Error bars represent standard deviation. B, rWheIF3c (150 pmol) or nWheIF3 (50 pmol) was incubated with CK2α1 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Reactions were stopped by the addition of ∼1 ml of cold HMK buffer. Samples were immediately captured on a nitrocellulose filter and quantitated using a scintillation counter. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and the results were averaged. Error bars represent standard deviation.

eIF4B

A response similar to AteIF2β was seen with A. thaliana eIF4B1 and eIF4B2, where the presence of CK2β subunits increased phosphorylation by 1.2–28 times (Fig. 6). For both isoforms of eIF4B, CK2β3 produced the smallest increase in activity (1.2–9 times). In the case of AteIF4B1, CK2β1 and CK2β4 subunits caused the greatest increase in the level of phosphorylation (∼10 times), whereas the phosphorylation of AteIF4B2 by CK2α1 and CK2α2 was most dramatically increased by CK2β2 subunits (13 and 28 times, respectively). However, no obvious effect of holoenzyme formation on activity was detected for recombinant wheat eIF4B (Fig. 6). This less obvious reliance of wheat eIF4B on formation of CK2 holoenzymes for phosphorylation may reflect the difference in the number or character of CK2 sites between A. thaliana and wheat (6 and 2, respectively, see Table 1).

eIF5

The presence of CK2β subunits produced a differential effect on both A. thaliana and wheat eIF5 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). For AteIF5, CK2β3 showed a modest increase in activity; however, no significant reduction in activity toward AteIF5 was seen in the presence of any CK2β subunits (Fig. 6). The activity of CK2α1 and CK2α2 toward wheat eIF5 was slightly increased by the presence of CK2β3 (∼1.3–1.5 times), whereas the presence of CK2β1 reduced the activity of both catalytic subunits, although somewhat less so in the case of CK2α2 (Fig. 6). These results for eIF2β, eIF3c, and eIF5 show that differential expression or availability of plant CK2 subunits may affect phosphorylation of these substrates and thus provide differential regulation.

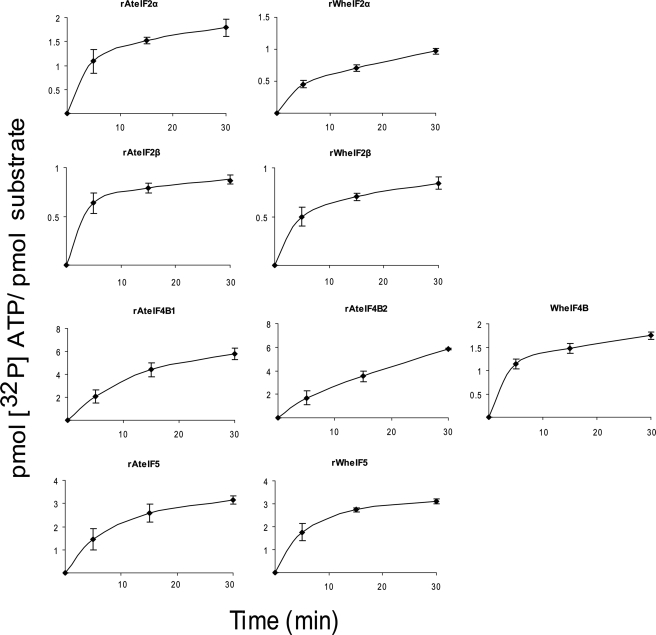

Quantitation of Phosphorylation Sites of Plant Initiation Factors by CK2

The approximate number of phosphorylation sites on each initiation factor was determined by the incorporation of 32P into each protein (summarized in Table 1). CK2α1 was used to phosphorylate eIF2α, eIF3c, eIF4B, and eIF5, whereas CK2α1β4 was used to phosphorylate eIF2β. This decision was made based on the optimum combination of subunits for phosphorylation observed in Fig. 6. At saturation, rWheIF2α, rWheIF2β, and rAteIF2β appear to have only a single CK2 phosphorylation site. However, multiple phosphorylation sites appear to be present in rAteIF2α, rAteIF4B1, rAteIF4B2, rAteIF5, rWheIF3c, rWheIF4B, and rWheIF5 (Figs. 7 and 8). These data and the predicted number of phosphorylation sites are summarized in Table 1. The location of many of these phosphorylation sites has been determined by mass spectrometry and confirmed by mutagenesis (47).

FIGURE 8.

Quantitative phosphorylation of plant initiation factors by CK2. rAteIF2α (250 pmol), rAteIF2β (250 pmol), rAteIF4B1(150 pmol), rAteIF4B2 (150 pmol), and rAteIF5 (250 pmol) and rWheIF2α (250 pmol), rWheIF2β (250 pmol), rWheIF4B (250 pmol), or rWheIF5 (250 pmol) were incubated with CK2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Reactions were stopped by the addition of ∼1 ml of cold HMK buffer. Samples were immediately captured on a nitrocellulose filter and quantitated using a scintillation counter. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and the results were averaged. Error bars represent standard deviation. CK2α1 was used to phosphorylate rWheIF2α, rAteIF5, rWheIF5, and rWheIF4B. CK2α1β4 was used to phosphorylate AtreIF2β, rWheIF2β, rAteIF4B1, and rAteIF4B. Because CK2β4 undergoes autophosphorylation, a separate blank was run for this reaction. Note that scales for the y axis vary.

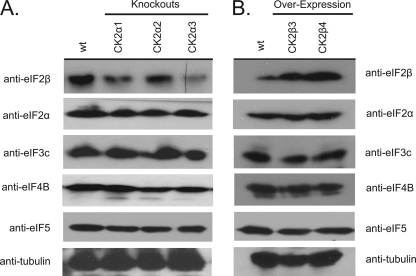

Effect on Stability of CK2 Substrates in Transgenic A. thaliana

Recently CK2 phosphorylation was shown to play a role in preventing degradation of the transcription factor HFR1 (38). To determine whether CK2 phosphorylation could play a role in the stability of initiation factors that are CK2 substrates, the levels of various initiation factors in transgenic A. thaliana lines were evaluated by immunoblotting. Extracts from both CK2α-subunit knock-outs (CK2α1, CK2α2, and CK2α3) and plants overexpressing CK2β3 (30) and CK2β4 (17) were used to compare the various levels of initiation factors. There were no obvious differences in the amounts eIF2α, eIF3c, eIF4B, or eIF5 in the transgenic A. thaliana lines (Fig. 9). However, compared with wild-type A. thaliana, the amount of eIF2β detected in CK2α knock-out plants appears to be significantly reduced (Fig. 9A), whereas the amount of eIF2β is increased in lines overexpressing CK2β3 and CK2β4 subunits (Fig. 9B). To determine whether this was a direct or indirect effect on stability of eIF2β by CK2 phosphorylation, wheat eIF2β and a mutant form of eIF2β that was mutated to remove the CK2 sites (47) were incubated with wheat germ extract in the presence and absence of exogenous CK2 holoenzyme (eIF2β requires holoenzyme for phosphorylation and wheat germ extract appears to deficient in CK2β). Interestingly, the mutant form of eIF2β was degraded only in the presence of CK2, whereas the wild-type form was unexpectedly stable in the absence of CK2 (see supplemental material). This suggests that there may be upstream effects of CK2 on either the degradation machinery or other ancillary factors. A proteosome inhibitor (MB132) prevented the degradation of the mutant form of eIF2β (see supplemental material) suggesting that CK2 phosphorylation may have both a direct and indirect role in the degradation of eIF2β. It is interesting to note that of the initiation factor substrates only eIF2β stability appears to be affected in the CK2 mutant lines, and eIF2β is the only initiation factor substrate identified that requires the holoenzyme for phosphorylation. These data suggest that the phosphorylation of eIF2β may have a distinctly different biological role than phosphorylation of the other initiation factors. Our accompanying paper (47) addresses a functional role for CK2 phosphorylation of eIF3c and eIF5 in plant translation initiation.

FIGURE 9.

Stability of eIF2β in CK2α-subunit knock-out lines or CK2β-subunit overexpression lines. Extracts from both CK2α1, CK2α2, and CK2α3-subunit knock-outs (A) and plants overexpressing CK2β3 and CK2β4 (B) were used to compare the various levels of initiation factor expression. Transgenic A. thaliana plant extract (15 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride. Rabbit antiserum to recombinant wheat eIF2β, eIF2α, eIF3c, eIF4B, and eIF5 or mouse monoclonal α-tubulin antibodies were used for Western blots as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

DISCUSSION

A. thaliana CK2 subunits were expressed and purified and shown to have enzymatic activity similar to CK2 isolated from wheat germ. In addition to phosphorylating the previously identified wheat translation initiation factor substrates eIF2α and eIF3c, CK2 was observed to phosphorylate wheat eIF2β, eIF4B, and eIF5 and A. thaliana eIF2α, eIF2β, eIF4B1, eIF4B2, and eIF5. CK2 did not phosphorylate recombinant wheat eIF1, eIF1A, eIF4A, eIF4E, eIF4G, eIFiso4G, or eIFiso4E. In addition, T-substrate (23) was identified as plant histone deacetylase 2B.

In previous studies, the phosphorylation of native wheat eIF2β was not observed in the presence of native wheat germ kinase (22). This is because of the presumed low levels of the regulatory CK2β subunit in wheat germ extracts (data not shown). Similar findings were observed with recombinant A. thaliana CK2 subunits, where phosphorylation of eIF2β occurs only in the presence of regulatory CK2β subunits. The work presented demonstrates that holoenzyme formation of catalytic CK2α subunits with various regulatory CK2β subunits alters the ability of A. thaliana CK2 to phosphorylate plant initiation factor substrates in vitro. More specifically, when assembled into holoenzymes with CK2β, CK2α subunits exhibit an increase in the phosphorylation of eIF2β and in some cases eIF4B; however, a reduction in the ability to phosphorylate eIF3c was observed for the holoenzyme, suggesting the potential for differential regulation by the availability of various CK2 subunits. This is the first study to clearly demonstrate the differential effects of various CK2β subunits on substrate specificity. By regulating specificity, the formation of various CK2 holoenzymes presents an attractive mechanism for altering the phosphorylation state of various physiological substrates.

It has been previously shown that A. thaliana CK2β subunits exhibit differential subcellular distribution (14), and DNA array data bases indicate that A. thaliana regulatory CK2 subunit mRNAs are differentially expressed in specific tissues during development and in response to stresses (see supplemental material for summary). Similar findings demonstrate the differential expression of CK2 subunit mRNA in maize during development (10) and in tobacco during the cell cycle (15). The phosphorylation data presented here support the possibility that the regulated expression of CK2β subunits in plants could be used to modify the substrate specificity of CK2 subunits toward various substrates in vivo by controlling regulatory subunit availability.

A number of in vivo CK2 phosphorylation sites have been identified in translation initiation factors from yeast and mammalian cells (3); however, the exact role CK2 phosphorylation plays in translation is not fully known. CK2 phosphorylation sites in mammalian eIF2β, eIF2B, and eIF5 appear to be necessary for the proper regulation of translation (39–41). The phosphorylation of mammalian eIF2β by CK2 leads to a reduction in its affinity for GDP (42), and alanine substitution to prevent CK2 phosphorylation results in reduced rates of protein synthesis (40). Furthermore, phosphorylation of mammalian eIF2B on its ϵ-subunit by CK2 stimulates nucleotide exchange activity (40, 42) and is required for interaction of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor with eIF2 in vivo (43). In both of these instances, CK2 phosphorylation would appear to enhance the recycling of eIF2-GDP and improve ternary complex formation. Similarly, alanine substitution at CK2 phosphorylation sites in mammalian eIF5 limits its interaction with eIF2 and thus the formation of multifactor complexes, leading to a disruption in synchronous cell progression and reduced growth rates (41). Additional studies have implicated CK2 in the phosphorylation of mammalian eIF4E and eIF4B (3); however, the effect phosphorylation has on the activity of these factors is less clear. This work shows that plant eIF4E is not a CK2 substrate, although eIF4B is a substrate. In mammalian cells, CK2 has also been found to phosphorylate and up-regulate the activity of Akt/protein kinase B, suggesting a potential role for the kinase in regulating translation initiation via the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway (44). Compared with other eukaryotes, plants possess a wider variety of CK2 isoforms, and the regulation of CK2 subunit expression/degradation and variations in the subcellular distribution of the CK2 isoforms presents a potential mechanism for regulating the substrate specificity of CK2 through the formation of different CK2 holoenzyme complexes.

CK2 may also function in regulating protein levels by promoting ubiquitin-mediated degradation. The ubiquitination and degradation of mammalian IκBα (45) and promyelocytic leukemia (46) have been shown to be dependent on direct phosphorylation by CK2. More recently, CK2 phosphorylation sites in the A. thaliana transcription factor HFR1 were shown to influence the rate of protein degradation, as a phosphorylation-deficient A. thaliana HFR1 mutant protein was degraded faster in vitro (38). In the case of HFR1, Park et al. (38) have suggested a mechanism whereby CK2 phosphorylation reversibly regulates HFR1 interaction with the COP1-SPA1 ubiquitin-protein isopeptide (E3) ligase complex. Our analysis of initiation factors in A. thaliana extracts from CK2α knock-out lines and CK2β overexpression lines suggests that a similar protective mechanism may be taking place for A. thaliana eIF2β, although it appears that there may be upstream or indirect effects by CK2 on eIF2β stability. Further research is necessary to understand any potential relationship between phosphorylation by CK2 holoenzyme and degradation pathways for eIF2β.

The findings of this study suggest a potential role for CK2 isoforms in regulating plant translation initiation. The regulated expression/degradation of various CK2 subunits presents a potential mechanism for altering the phosphorylation of various initiation factors in plants. Because there is limited evidence that plants regulate their translational machinery through similar mechanisms compared with other eukaryotes, it is tempting to speculate a potential role for CK2 in regulating plant translation initiation. By differential phosphorylation of initiation factor complexes, CK2 may regulate the translation of specific mRNAs or the stability of various initiation factors in response to abiotic or biotic stress, development, or changes in the cell cycle. This study represents a starting point for evaluating the role CK2 phosphorylation plays in regulating the initiation of translation in plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Mayberry and Dr. Andrew Lellis for technical advice; Tanya Trynosky (undergraduate student) and Isaac Hernandez (National Science Foundation Research Experience for Undergraduate Students CHE 0552422) for assistance in the preparation of CK2 proteins; and Dr. David Graham for use of the FPLC Sephacryl S-200 HR gel filtration column and Dr. Jon Robertus for the use of the FPLC HiLoad 16/60 Superdex S200 column. Transgenic A. thaliana lines overexpressing CK2β3 or CK2β4 were generously provided by Dr. Elaine Tobin (UCLA) and Dr. Paloma Mas (Consorcio Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentàries, Barcelona, Spain), respectively. T-DNA insertion lines for CK2α1, CK2α2, and CK2α3 were generously provided by Dr. Q. Bu (University of Texas, Austin). Mass spectrometry was performed by the University of Texas Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology Analytical Instrumentation Facility Core (Dr. Maria Person, Director).

This work was supported by Grant DE-FG02-04ER15575 from the United States Department of Energy, Grant MCB0214996 from the National Science Foundation, and Grant F1339 from The Welch Foundation (to K. S. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Results,” a figure, and a table.

Mayberry, L. K., Allen, M. L., Dennis, M. D., and Browning, K. S., (2009) Plant Physiol., in press.

- HD2B

- histone deacetylase 2B

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- FPLC

- fast protein liquid chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinna L. A. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 3873–3878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litchfield D. W. (2003) Biochem. J. 369, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meggio F., Pinna L. A. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 349–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsten M. E., Litchfield D. W. (2004) Biochem. Cell Biol. 82, 681–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsten M. E., Weber J. E., Litchfield D. W. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 274, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boldyreff B., Meggio F., Pinna L. A., Issinger O. G. (1994) Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 40, 391–399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meggio F., Ruzzene M., Sarno S., Pagano M. A., Pinna L. A. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed J. C., Bidwai A. P., Glover C. V. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18192–18200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubiński K., Domańska K., Sajnaga E., Mazur E., Zieliński R., Szyszka R. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 295, 229–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riera M., Peracchia G., Pagès M. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 227, 119–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarno S., Ghisellini P., Pinna L. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22509–22514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benaim G., Villalobo A. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 3619–3631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinna L. A. (2003) Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 378–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinas P., Fuentes D., Vidal E., Jordana X., Echeverria M., Holuigue L. (2006) Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1295–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espunya M. C., López-Giráldez T., Hernan I., Carballo M., Martínez M. C. (2005) J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3183–3192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C., Vilk G., Canton D. A., Litchfield D. W. (2002) Oncogene 21, 3754–3764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perales M., Portolés S., Más P. (2006) Plant J. 46, 849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riera M., Pages M., Issinger O. G., Guerra B. (2003) Protein Expr. Purif. 29, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Browning K. S. (2004) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 589–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallie D. R. (2007) in Translational Control in Biology and Medicine ( Mathews M. B., Sonenberg N., Hershey J. W. B., eds) pp. 747–774, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan T. F., Tao M. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7044–7049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browning K. S., Yan T. F., Lauer S. J., Aquino L. A., Tao M., Ravel J. M. (1985) Plant Physiol. 77, 370–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan T. F., Tao M. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7037–7043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lax S. R., Lauer S. J., Browning K. S., Ravel J. M. (1986) Methods Enzymol. 118, 109–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayberry L. K., Browning K. S. (2006) Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 16K.1.1–16K.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen J., Pavone A., Mikulec C., Hensley S. C., Traner A., Chang T. K., Person M. D., Fischer S. M. (2007) J. Proteome Res. 6, 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayberry L. K., Dennis M. D., Leah Allen M., Ruud Nitka K., Murphy P. A., Campbell L., Browning K. S. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 430, 397–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang L. Y., Yang W. Y., Browning K., Roth D. (1999) Plant Mol. Biol. 41, 363–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz A. M., Browning K. S. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342, 187–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugano S., Andronis C., Ong M. S., Green R. M., Tobin E. M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12362–12366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orrù S., Aspesi A., Armiraglio M., Caterino M., Loreni F., Ruoppolo M., Santoro C., Dianzani I. (2007) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 382–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abramczyk O., Zień P., Zieliński R., Pilecki M., Hellman U., Szyszka R. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szebeni A., Hingorani K., Negi S., Olson M. O. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9107–9115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Marchis M. L., Giorgi A., Schininà M. E., Bozzoni I., Fatica A. (2005) RNA 11, 495–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nusspaumer G., Remacha M., Ballesta J. P. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6075–6084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagano M. A., Sarno S., Poletto G., Cozza G., Pinna L. A., Meggio F. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 274, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heazlewood J. L., Durek P., Hummel J., Selbig J., Weckwerth W., Walther D., Schulze W. X. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D1015–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park H. J., Ding L., Dai M., Lin R., Wang H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23264–23273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llorens F., Duarri A., Sarró E., Roher N., Plana M., Itarte E. (2006) Biochem. J. 394, 227–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dholakia J. N., Wahba A. J. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 51–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homma M. K., Wada I., Suzuki T., Yamaki J., Krebs E. G., Homma Y. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15688–15693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh L. P., Arorr A. R., Wahba A. J. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 9152–9157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X., Paulin F. E., Campbell L. E., Gomez E., O'Brien K., Morrice N., Proud C. G. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4349–4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Maira G., Salvi M., Arrigoni G., Marin O., Sarno S., Brustolon F., Pinna L. A., Ruzzene M. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12, 668–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato T., Jr., Delhase M., Hoffmann A., Karin M. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scaglioni P. P., Yung T. M., Cai L. F., Erdjument-Bromage H., Kaufman A. J., Singh B., Teruya-Feldstein J., Tempst P., Pandolfi P. P. (2006) Cell 126, 269–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dennis M. D., Person M. D., Browning K. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20615–20628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.