Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) signaling by the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) is dependent on focal adhesions, which contain diverse structural and signaling proteins including protein phosphatases. We examined here the role of protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) α in regulating IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling in fibroblasts. IL-1 promoted recruitment of PTPα to focal adhesions and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) fractions, as well as tyrosine phosphorylation of the ER Ca2+ release channel IP3R. In response to IL-1, catalytically active PTPα was required for Ca2+ release from the ER, Src-dependent phosphorylation of IP3R1 and accumulation of IP3R1 in focal adhesions. In pulldown assays and immunoprecipitations PTPα was required for the association of PTPα with IP3R1 and c-Src, and this association was increased by IL-1. Collectively, these data indicate that PTPα acts as an adaptor to mediate functional links between focal adhesions and the ER that enable IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling.

The interleukin-1 (IL-1)3 family of pro-inflammatory cytokines mediates host responses to infection and injury. Impaired control of IL-1 signaling leads to chronic inflammation and destruction of extracellular matrices (1, 2), as seen in pathological conditions such as pulmonary fibrosis (3), rheumatoid arthritis (4, 5), and periodontitis (6). IL-1 elicits multiple signaling programs, some of which trigger Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as well as expression of multiple cytokines and inflammatory factors including c-Fos and c-Jun (7, 8), and matrix metalloproteinases (9, 10), which mediate extracellular matrix degradation via mitogen-activated protein kinase-regulated pathways (11).

In anchorage-dependent cells including fibroblasts and chondrocytes, focal adhesions (FAs) are required for IL-1-induced Ca2+ release from the ER and activation of ERK (12–14). FAs are actin-enriched adhesive domains composed of numerous (>50) scaffolding and signaling proteins (15–17). Many FA proteins are tyrosine-phosphorylated, including paxillin, focal adhesion kinase, and src family kinases, all of which are crucial for the assembly and disassembly of FAs (18–21). Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation plays a central role in regulating many cellular processes including adhesion (22, 23), motility (24), survival (25), and signal transduction (26–29). Phosphorylation of proteins by kinases is balanced by protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTP), which can enhance or attenuate downstream signaling by dephosphorylation of tyrosine residues (30–32).

PTPs can be divided into two main categories: receptor-like and intracellular PTPs (33). Two receptor-like PTPs have been localized to FA (leukocyte common antigen-related molecule and PTPα). Leukocyte common antigen-related molecule can dephosphorylate and mediate degradation of p130cas, which ultimately leads to cell death (34, 35). PTPα contains a heavily glycosylated extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and two intracellular phosphatase domains (33, 36). The amino-terminal domain predominantly mediates catalytic activity, whereas the carboxyl-terminal domain serves a regulatory function (37, 38). PTPα is enriched in FA (23) and is instrumental in regulating FA dynamics (39) via activation of c-Src/Fyn kinases by dephosphorylating the inhibitory carboxyl tyrosine residue, namely Tyr529 (22, 40–42) and facilitation of integrin-dependent assembly of Src-FAK and Fyn-FAK complexes that regulate cell motility (43). Although PTPα has been implicated in formation and remodeling of FAs (44, 45), the role of PTPα in FA-dependent signaling is not defined.

Ca2+ release from the ER is a critical step in integrin-dependent IL-1 signal transduction and is required for downstream activation of ERK (13, 46). The release of Ca2+ from the ER depends on the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R), which is an IP3-gated Ca2+ channel (47). All of the IP3R subtypes (subtypes 1–3) have been localized to the ER, as well as other the plasma membrane and other endomembranes (48–50). Further, IP3R may associate with FAs, enabling the anchorage of the ER to FAs (51, 52). However, the molecule(s) that provide the structural link for this association has not been defined.

FA-restricted, IL-1-triggered signal transduction in anchorage-dependent cells may rely on interacting proteins that are enriched in FAs and the ER (53). Here, we examined the possibility that PTPα associates with c-Src and IP3R to functionally link FAs to the ER, thereby enabling IL-1 signal transduction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Fibronectin, poly-l-lysine, doxycycline, radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and mouse monoclonal antibodies to vinculin and β-actin were obtained from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to phospho-PTPα (Tyr789), as well as mouse monoclonal antibodies to phospho-Src (Tyr529 and Tyr419) were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). PTPα antibody directed against domain 2 was from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. (Lake Placid, NY). HA antibody was from Bethy Laboratories (Montgomery, TX). Mouse monoclonal anti-calnexin was obtained from BD Biosciences (Mississauga, Canada). Rabbit polyclonal anti-IP3R1 was obtained from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Goat anti-integrin α5β1 was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). FuGENE 6 transfection reagent and Fyn kinase were purchased from Invitrogen. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B, thrombin protease, GSTrap 4B, GSTrap FF, and HiTrap Benzamidine FF were purchased from GE Healthcare. Recombinant human IL-1β was obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fura-2/AM and mag-fura-2/AM were obtained from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR).

Cell Culture

Human gingival fibroblasts were grown in minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Rat2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum. Wild-type (PTPα+/+) and PTPα-null (PTPα−/−) fibroblasts were provided by Dr. Jan Sap (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) (41). In some experiments, PTPα−/− cells were transfected with wild-type PTPα and designated as PTPαRescue. Genetically modified NIH3T3 fibroblasts that express HA-tagged wild-type PTPα (NIH3T3PTPα) and C433S/C723S double mutant PTPα (NIH3T3CCSS) under control of a doxycycline sensitive repressor were obtained from David Shalloway (Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) and were generated as previously described (54). The latter cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum in the presence of 5 ng/ml doxycycline. Prior to experiments doxycycline was removed (14–16 h before) to allow expression of recombinant PTPα.

Plasmid Constructs and Transient Transfection

HA-tagged wild-type PTPα, PTPα lacking the D2 domain (PTPαΔD2) and PTPα lacking the D1 and D2 domains (PTPαΔD1/D2) were kindly provided by Dr. J. den Hertog (Hubrecht Laboratory, Netherlands Institute for Developmental Biology, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The cells were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 105/well 24 h before transfection to yield a 30–40% confluent culture on the day of transfection. Transient transfections were performed using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the cells were incubated with DNA-FuGENE 6 reagent (1:3) complexes for 5–7 h. Within 48 h after transfection, the cells were subjected to further experiments.

Short Interfering RNA (siRNA)

Specific knockdown of PTPα expression was conducted with commercially available siRNA against PTPα (Qiagen). Human gingival fibroblasts were transfected with PTPα siRNA or GFP-siRNA (control) using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The cells were washed in PBS and lysed with SDS-lysis buffer. The lysates were collected, and measurement of the gene knockdown was preformed 24–72 h after transfection by Western blotting.

Isolation of Focal Adhesions

The cells were grown to 80–90% confluence on 60-mm tissue culture dishes and were cooled to 4 °C prior to the addition of collagen or BSA-coated magnetite beads. Focal adhesion complexes were isolated from cells after specific incubation time periods as described (55). In brief, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound beads and scraped into ice-cold cytoskeleton extraction buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mm NaCl, 300 mm sucrose, 3 mm MgCl2, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mm PIPES, pH 6.8). The cell-bead suspension was sonicated for 10 s (output setting 3, power 15% Branson), and the beads were isolated from the lysate using a magnetic separation stand. The remainder of the lysates was used to assess the non-focal adhesion fraction. The beads were resuspended in fresh ice-cold cytoskeleton extraction buffer, homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer (20 strokes), and reisolated magnetically. The beads were washed in CSKB, sedimented with a microcentrifuge, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and placed in a boiling water bath for 3–5 min to allow the collagen-associated complexes to dissociate from the beads. The beads were sedimented, and lysates were collected for analysis.

Subcellular Fractionation

Subcellular fractionation was performed as previously described (56), and the cells were harvested, resuspended in an isotonic buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 100 mm CaCl2, 200 mm sucrose), and disrupted by Dounce homogenization followed by 20 strokes. The homogenate was spun at 800 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was recovered and further centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 × g. The resulting supernatant was further spun for 1.5 h at 28,000 × g. The resulting pellet constituted the microsomal ER fraction. The specificity of the ER fraction was confirmed by immunoblotting with the ER-specific protein calnexin.

Immunoblotting

The protein concentrations of cell lysates were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels (10% acrylamide), resolved by electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline solution with 5% milk or 0.2% BSA to block nonspecific binding sites. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20. Horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% milk or 0.2% BSA. Labeled proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence as per the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences, Oakville, Canada).

Immunoprecipitation

The cells were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 1% deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm Na3VO4) containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. Equal amounts of protein from cleared extracts were subjected to standard immunoprecipitation or immunoblotting procedures.

GST Pulldown Experiments

GST-cPTPα (residues 167–793, full cytoplasmic domain), GST-PTPαD1 (residues 167–503, domain 1), and GST-PTPαD2 (residues 504–793, domain 2) were kindly provided by Dr. J. den Hertog (Hubrecht Laboratory, Netherlands Institute for Developmental Biology, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The cells were isolated by scraping and lysed for 10 min on ice in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 900 × g for 3 min to remove insoluble debris. The supernatants were removed and stored at −80 °C until use. The cell lysates were precleared with 50 μl of 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (1× PBS) and 25 μg of GST for 2 h at 4 °C. The Sepharose matrix was removed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were subsequently incubated with 50 μl of glutathione-Sepharose 4B, 5 mg of GST protein in PBS + 1% Triton X-100 with gentle agitation at room temperature for 30 min. The matrix was recovered by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The glutathione-Sepharose 4B pellet was washed four times with 1 ml of PBS. GST was eluted from the glutathione-Sepharose 4B matrix by incubating twice with 50 μl of elution buffer (10 mm reduced glutathione in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for 10 min at room temperature and isolated by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and pooling the supernatants. The samples were boiled for 5 min and analyzed by immunoblotting.

In Vitro Phosphorylation

For in vitro phosphorylation using Fyn, immunoprecipitates bound to protein A-Sepharose beads were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in 20 μl of kinase buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.1, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm MnCl2, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 100 μm MgATP) in the presence of 5 units of active Fyn. The reaction products were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against phosphotyrosine.

Calcium Signals

For measurement of whole cell [Ca2+]i, cells on coverslips were loaded with 3 μm fura-2/AM for 20 min at 37 °C. For estimating [Ca2+]ER, the cells were incubated with mag-fura-2/AM (4 μm) for 150 min at 37 °C in culture medium and measured by ratio fluorimetry as described (13). The nominally calcium-free buffer consisted of a bicarbonate-free medium containing 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCI, 10 mm d-glucose, 1 mm MgSO4, 1 mm Na2HPO4, and 20 mm HEPES at pH 7.4 with an osmolarity of 291 mOsm. For experiments requiring external Ca2+, 2 mm CaC12 was added to the buffer; for experiments requiring chelation of external Ca2+, 1 mm EGTA was added. After incubation with fura-2/AM, inspection of cells by fluorescence microscopy demonstrated no vesicular compartmentalization of fura-2, suggesting that the dye loading method permitted measurement of cytosolic [Ca2+]i. Visual inspection of mag-fura-2-loaded cells showed fluorescent labeling of intracellular organelles. Whole cell [Ca2+]i measurements and mag-fura-2 ratios were obtained with C·IMAGING SYSTEMS (Compix, Inc., Cranberry, PA) with excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm. Changes in [Ca2+]i were monitored by the ratio of fura-2 fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm.

Data Analysis

The means ± S.E. were calculated for [Ca2+]i measurements including base-line [Ca2+]i, net change in [Ca2+]i above base line, and the mag-fura-2 ratios. For continuous variables, the means ± S.E. were computed, and when appropriate, comparisons between two groups were made with the unpaired Student's t test or with analysis of variance for multiple samples. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. For all of the experiments, n ≥ 3 replicates were used.

RESULTS

PTPα Is Necessary for IL-1-induced Ca2+ Signaling

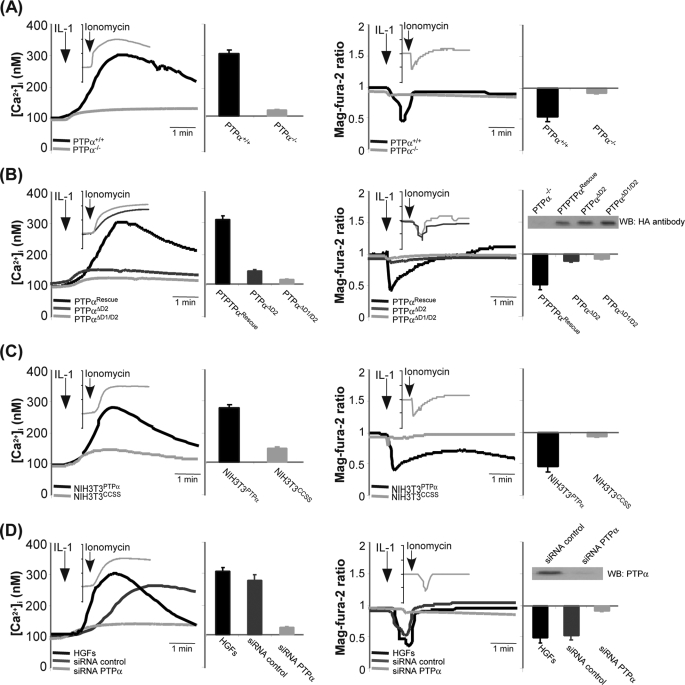

IL-1 triggers focal adhesion-dependent Ca2+ release from the ER (12, 57). Because PTPα is critical for regulating the formation and maturation of focal adhesions (23, 44), we determined whether PTPα regulates variations in the concentrations of cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ([Ca2+]ER) in response to IL-1. In PTPα wild-type primary murine fibroblasts (PTPα+/+), IL-1 treatment increased [Ca2+]i and caused a transient release of Ca2+ from the ER (Fig. 1 A). By contrast, the amplitude of IL-1-induced Ca2+ signals was reduced by >8-fold (p < 0.001) in PTPα-null primary mouse fibroblasts (PTPα−/−). Although IL-1-induced induced Ca2+ flux was fully restored by transfection with wild-type PTPα (PTPαRescue; Fig. 1B), by comparison there was a >5-fold lower response (p < 0.001) in cells transfected with either PTPαΔD2 (PTPα lacking the catalytically active domain 2) or with PTPαΔD1/D2 (PTPα lacking both catalytic domains 1 and 2). Similarly cells expressing catalytically inert PTPα (C433S/C723S; designated NIH3T3CCSS; Fig. 1C) exhibited a >4-fold smaller [Ca2+]i response and an 8-fold smaller [Ca2+]ER response than cells expressing wild-type PTPα (designated NIH3T3PTPα). Finally, in human gingival fibroblasts, knockdown of PTPα using siRNA resulted in a >6-fold (p < 0.001) lower amplitude of IL-1-induced [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]ER responses (Fig. 1D). Taken together these data clearly indicate that intact catalytic activity of PTPα is essential for the IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling.

FIGURE 1.

PTPα is required for IL-1-induced Ca2+ release from the ER. Intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) or mag-fura-2 ratios were measured in fura-2 or mag-fura-2-loaded cells after treatment with IL-1. Insets, ionomycin as positive control. A, response of PTPα+/+ and PTPα−/− primary mouse fibroblasts cells. B, response of PTPαRescue, PTPαD1/ΔD2 and PTPαΔD1/ΔD2 cells. Inset: Western blot for HA-tagged shows the presence of PTPα in cells transfected with mutant constructs. C, responses of NIH3T3PTPα and NIH3T3CCSS cells. D, responses of human gingival fibroblasts or human gingival fibroblasts transfected with irrelevant GFP-siRNA (siRNA control) and PTPα -siRNA (siRNA PTPα). Inset, Western blot for PTPα illustrates specific knockdown of PTPα in PTPα-siRNA treated cells.

Spatial Relationships between PTPα and FA- and ER-associated Proteins

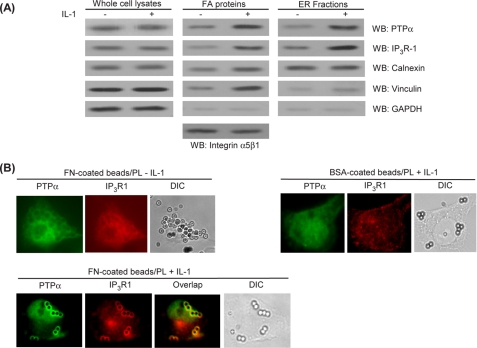

The dependence of IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling on PTPα motivated us to determine whether IL-1 affects the association of PTPα with focal adhesion- and ER-associated proteins. After IL-1 treatment, the relative abundance of PTPα and IP3R1 (the ER calcium release channel isoform that is most abundant in fibroblasts (58)) was increased in focal adhesion preparations (which also contain substantial amounts of plasma membrane) and in ER fractions (Fig. 2A). By contrast, the relative abundance of the loading control proteins α5β1 integrin (in focal adhesion fractions) and calnexin (in ER fractions) was unchanged by IL-1 treatment. We also found marked, IL-1-induced increases of vinculin in focal adhesion preparations, indicating that IL-1 enhanced the maturation of focal adhesions (44). Vinculin was almost undetectable in the ER fraction.

FIGURE 2.

PTPα co-localizes with ER-associated proteins in focal adhesions. A, whole cell lysates, focal adhesion proteins, and ER fractions prepared from Rat2 cells previously treated with IL-1 (+) or vehicle (−). The lysates were immunoblotted for PTPα, IP3R1, calnexin, vinculin, and GAPDH. B, Rat2 cells plated for 3 h on PL-coated glass coverslips that were preincubated with FN- or BSA-coated latex beads. In untreated cells or after stimulation with IL-1, the cells were co-immunostained for PTPα/IP3R1 and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. WB, Western blotting.

We examined the localization of PTPα relative to focal adhesions and ER-associated proteins using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cells plated on FN or BSA latex beads dispersed on poly-l-lysine substrates. Plating cells on poly-l-lysine coatings restricts focal adhesion formation to fibronectin bead sites in this system (58). Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy analysis revealed that co-localization of IP3R1 with PTPα occurred only after IL-1 treatment and only around FN-coated (but not BSA-coated) beads (Fig. 2B).

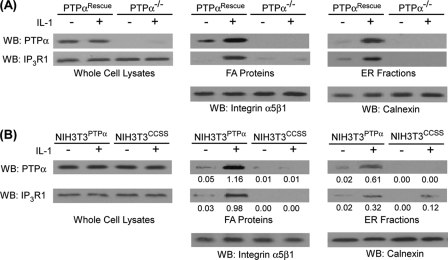

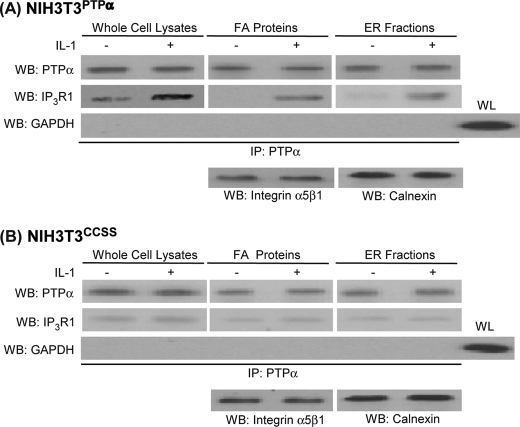

The relative abundance of IP3R1 and PTPα in whole cell lysates, focal adhesion preparations or ER fractions was examined by immunoblotting lysates prepared from PTPα−/− cells or PTPα−/− cells transfected with wild-type PTPα (PTPαRescue). IL-1 treatment enhanced accumulation of IP3R1 in focal adhesions and ER fractions in PTPαRescue cells but not in PTPα−/− cells (Fig. 3A). We next found that IL-1 promoted the recruitment of PTPα and IP3R1 to focal adhesions and ER fractions in NIH3T3 cells expressing wild-type PTPα (NIH3T3PTPα), but this effect was much smaller in NIH3T3CCSS cells (Fig. 3B). Immunoblot analysis of PTPα immunoprecipitates from NIH3T3PTPα cells showed that IP3R1 co-precipitated with PTPα derived from whole cell lysates, focal adhesion preparations, and ER preparations, and these associations were markedly increased after IL-1 treatment (Fig. 4A). By contrast, in NIH3T3CCSS cells, almost no IP3R1 co-precipitated with PTPα in cells expressing the catalytically inactive PTPα (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 3.

PTPα is required for IP3R1 recruitment to focal adhesion and ER. Whole cell lysates, focal adhesion proteins, and ER fractions prepared from the following cells were immunoblotted for PTPα and IP3R1 following induction with (+) or without (−) IL-1. A, PTPα−/− cells or PTPα−/− cells transfected with wild-type PTPα (PTPαRescue). B, NIH3T3PTPα and NIH3T3CCSS cells. The numbers beneath the blots in B represent the ratios of PTPα or IP3R1 to the α5β1 integrin or calnexin controls. WB, Western blotting.

FIGURE 4.

PTPα associates with IP3R1. PTPα was immunoprecipitated (IP) from whole cell lysates, FA proteins, or ER fractions prepared from vehicle (−) or IL-1 (+) treated cells. A, NIH3T3PTPα cells; B, NIH3T3ccss cells. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for PTPα, IP3R1, or GAPDH. For loading controls, focal adhesion proteins were immunoblotted for α5β1 integrin, and for the ER fraction immunoblotting for calnexin was used. WB, Western blotting.

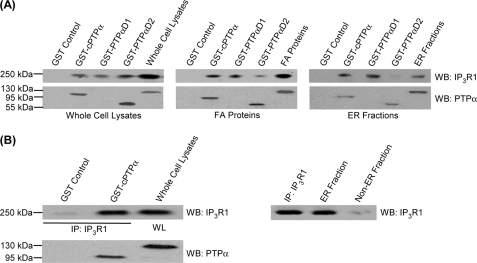

The associations of PTPα with IP3R1 were examined with pulldown assays using purified GST-cPTPα (cytosolic domain), GST-PTPαD1 or GST-PTPαD2 fusion proteins incubated with cell lysates, focal adhesion proteins, or ER fractions prepared from PTPαRescue cells. From immunoblots of IP3R1, we found that the cytoplasmic and D1 domains of PTPα associated with IP3R1 in the FA and ER fractions, more strongly than D2 domain (Fig. 5A). This association appeared to be direct because the purified, bacterially expressed GST fusion-cPTPα strongly bound to immunoprecipitated IP3R1, whereas immunoprecipitated IP3R1 showed no association with control GST beads (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

PTPα associates with IP3R1. GST pulldown experiments to show association between PTPα and IP3R1 in vitro are shown. A, glutathione-agarose (GST) beads bound to bacterially expressed cPTPα, cPTPαD1, or cPTPαD2 fusion proteins or GST control beads were incubated with whole cell lysates (WL), FA proteins, and ER fractions from PTPαRescue cells. The materials bound to the beads were analyzed by immunoblotting for IP3R1. Whole cell lysates, FA proteins, and ER fractions were also immunoblotted for IP3R1. Note that the protein products of the domain deleted constructs (cPTPαD1 or cPTPαD2) have lower molecular masses (∼60 kDa) compared with the cytosolic cPTPα (95 kDa) or full-length PTPα (130 kDa). B, GST-cPTPα or GST control fusion proteins were incubated with IP3R1 that was IP purified from whole cell lysates of PTPαRescue cells. WB, Western blotting.

IL-1 Regulates Tyrosine Phosphorylation of PTPα and Src to Mediate ER-Ca2+ Release

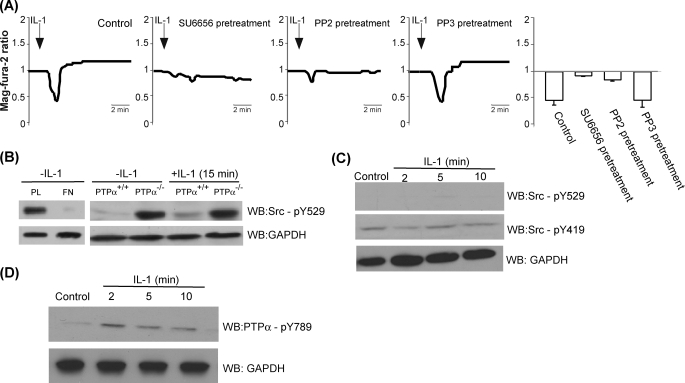

The optimum Ca2+ conductance of the IP3R release channel in the ER requires the activity of SFK such as c-Src and Fyn (59, 60), which in turn are regulated by PTPα (30, 31, 61). Accordingly, when we examined the IL-1-induced Ca2+ release from the ER of PTPα+/+ cells, the pronounced, short term release of Ca2+ was blocked in cells pretreated with the SFK inhibitors, SU6656, or PP2, but not in cells pretreated with the inactive structural analog PP3 (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Involvement of Src kinase and PTPα in IL-1-induced ER Ca2+ release. A, ER-Ca2+ release by IL stimulation was inhibited by Src kinase inhibitors SU6656 and PP-2, but not by the inactive analog PP3. PTPα+/+ cells were pretreated with vehicle control, SU6656 (5 μm for 1 h), PP2 (10 μm for 30 min), or PP3 (10 μm for 30 min) and stimulated with IL-1 prior to mag-fura-2-loading. The data in histograms are the means ± S.E. of mag-fura-2 ratios. B, left panel, Src activation requires integrin stimulation. Whole cell lysates of PTPα+/+ cells plated on PL or FN were immunoblotted for antibodies to phospho-Src (pY529) or GAPDH. Right panel, indicated cell types were treated with vehicle or IL-1 for 15 min and immunoblotted for phospho-Src (pY529). C, Src (pY529) levels remain low from 0–10 min after IL-1 treatment, whereas Src (pY419) remain constant. Whole cell lysates of PTPα+/+ cells were stimulated with IL-1 (20 ng/ml for 2, 15, or 10 min) or vehicle control and were immunoblotted for antibodies to phospho-Src (Tyr529) or phospho-Src (Tyr419) or GAPDH. D, levels of PTPα (Tyr789) after IL-1 treatment. PTPα+/+ cells were treated with or without IL-1 (20 ng/ml) for indicated time periods, and whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to PTPα (Tyr789) and GAPDH. WB, Western blotting.

The level of SFK activation can be estimated by the phosphotyrosine levels of inhibitory and stimulatory residues, Tyr529 and Tyr419 in rodents, respectively (22, 40, 62). First we examined the regulation of SFK activation using PTPα+/+ cells plated either on fibronectin (FN) or on poly-l-lysine (PL), conditions that either facilitate or block FA formation, respectively (57). In otherwise unstimulated PTPα+/+ cells, immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates with antibody to phospho-Src (Tyr(P)529) revealed very low levels of phosphorylation of the inhibitory tyrosine in cells plated on FN (focal adhesions are present) compared with cells plated on PL (focal adhesions are absent; Fig. 6B). These data are consistent with the observation that Src becomes activated via dephosphorylation of Tyr529 during adhesion and spreading on a fibronectin substrate, and this activation is dependent on and mediated by PTPα (24, 42). Further, in PTPα−/− cells, there was abundant phosphorylation of the inhibitory residues (Tyr529) of Src that was unchanged after IL-1 treatment (Fig. 6B), consistent with previous reports (40, 63). In PTPα+/+ cells, there was a modest increase in phosphorylation of Tyr529 Src, after 15 min of IL-1 treatment (Fig. 6B). This IL-1-induced inhibition of Src, however, was not evident at early time points, because the phosphorylation levels of inhibitory (Tyr529) and stimulatory (Tyr419) residues were relatively unchanged (Fig. 6C).

We investigated whether the ability of PTPα to dephosphorylate Src diminishes over time after IL-1 treatment. The phosphotyrosine displacement model by Zheng et al. (54) proposes that phosphorylation of tyrosine 789 of PTPα selectively promotes its phosphatase activity toward Src by enabling association with the SH2 domain of Src. Accordingly, when whole cell lysates from PTPα+/+ cells were treated with IL-1 or vehicle and then immunoblotted for phospho-PTPα (Tyr(P)789), we observed that there was an initial IL-1-induced phosphorylation of PTPα on Tyr789, which then decreased in a time-dependent manner after IL-1 treatment (Fig. 6D).

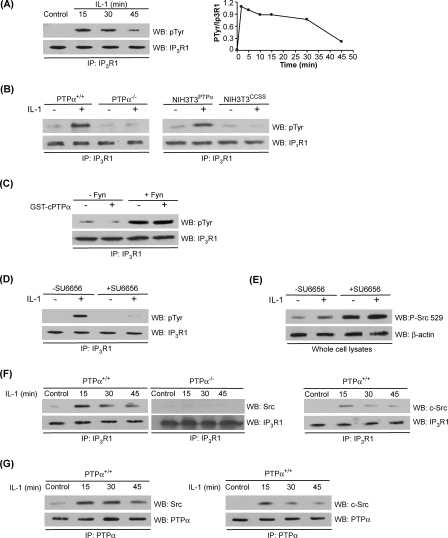

Functional Interactions between PTPα and IP3R

Because the tyrosine phosphorylation state of the IP3R dictates its Ca2+ conductance (64–66), we examined the effects of IL-1 and PTPα on the phosphorylation state of IP3R1, which is the most prominent isoform in fibroblasts (58). For this assay IP3R1 was immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates of PTPα+/+ and PTPα−/− murine fibroblasts, as well as genetically modified NIH3T3PTPα cells or cells with the catalytically inert PTPα mutant (NIH3T3CCSS) that had been treated with IL-1 or vehicle control and blotted with a phosphotyrosine antibody. In response to IL-1, phosphorylation of IP3R1 in PTPα+/+ was sharply increased (maximal at 2 min) and declined thereafter (Fig. 7A). Further, the phosphorylation of IP3R1 was dependent on the presence of catalytically active PTPα, because cells lacking PTPα or expressing the catalytically inactive (CCSS) PTPα showed no detectable IL-1-induced phosphorylation of IP3R1 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1: regulation by PTPα and Src. A, tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 rapidly increases after IL-1 treatment and then declines subsequently. IP3R1 was immunopurified (IP) from whole cell lysates of PTPα+/+ cells that had been stimulated with or without IL-1, and immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine (pTyr, upper panel). The lower panel shows protein levels of immunoprecipitated IP3R1. The line graph on the right shows the ratios of the blot densities of tyrosine-phosphorylated IP3R1 to IP3R1 over the full time course. B, tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 after IL-1 stimulation requires catalytically active PTPα. IP3R1 was immunopurified from whole cell lysates of PTPα+/+, PTPα−/−, NIH3T3PTPα, and NIH3T3CCSS cells that had been stimulated with (+) or without (−) IL-1. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine (pTyr, upper panel) or IP3R1 (lower panel). C, IP3R1 phosphorylation is not affected by PTPα. In vitro phosphorylation was analyzed by incubating immunopurified IP3R1 from wild-type PTPα cells in presence or absence of active Fyn and then incubated with GST-cPTPα fusion protein. Phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (pTyr, upper panel). The lower panel shows protein levels of immunopurified IP3R1. D, tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 is dependent on catalytically active SFK. IP3R1 was immunoprecipitated from PTPα+/+ cells that had been pretreated with SU6656 (5 μm for 1 h) or vehicle and then treated with (+) or without (−) IL-1. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine (pTyr, upper panel) or IP3R1 (lower panel). E, cells treated with Src inhibitor exhibit high levels of Src (Tyr(P)529). The cells were preincubated with SU6656 (5 μm for 1 h) and then treated with IL-1 (+) or vehicle (−) for 10 min. The cell lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylation of the carboxyl-terminal inhibitory tyrosine residue of Src (Tyr(P)529). F, IL-1 promotes association of IP3R1 with SFK and c-Src and PTPα is required for interactions between Src and IP3R1. Left panel, PTPα+/+ cells were stimulated with IL-1 as indicated. Middle panel, PTPα−/− cells were stimulated with IL-1 as indicated. IP3R1 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for either SFK (left and middle panels, Src) or c-Src (right panel). G, IL-1 promotes association of PTPα with SFK and c-Src. PTPα+/+ cells were stimulated with IL-1. PTPα immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for either SFK (left panel, Src) or c-Src (right panel). After longer exposure to IL-1, the association dissipated. WB, Western blotting.

We next considered whether IP3R1 immunopurified from wild-type PTPα cells could be directly dephosphorylated by PTPα. Purified IP3R1 bound to protein A-Sepharose beads was exposed to active Fyn in a kinase buffer to promote its tyrosine phosphorylation. Next, the phosphorylated IP3R1 protein was incubated with the recombinant cytosolic domain of PTPα. Active Fyn was able to phosphorylate IP3R1, but the recombinant cytoplasmic domain of PTPα was unable to dephosphorylate IP3R1 (Fig. 7C). As a control, recombinant cPTPα readily dephosphorylated recombinant SHP-2 (data not shown). Consequently, IP3R1 is not a direct substrate of PTPα. Instead, we considered that the ability of PTPα to activate SFK (c-Src or Fyn) may be achieved by dephosphorylating the carboxyl-terminal inhibitory tyrosine residue (Tyr(P)529 of Src), thereby enhancing the catalytic activity of these kinases (30, 31, 61). We examined this possibility by first pretreating wild-type PTPα cells with the SFK inhibitor, SU6656. This treatment blocked IL-1-induced phosphorylation of IP3R1 (Fig. 7D), indicating that the catalytic activity of SFK is required for IL-1-induced phosphorylation of the IP3R1. We confirmed the ability of SU6656 to reduce the catalytic activity of Src by examining the Tyr529 inhibitory residue of Src. For this experiment, PTPα wild-type cells were treated with SU6656 for 1 h and stimulated with or without IL-1 for 30 min. When the whole cell lysates were immunoblotted for Tyr(P)529, increased levels of Tyr(P)529 were observed after SU6656 treatment (Fig. 7E).

We examined whether SFKs associate with IP3R1 in response to IL-1. Wild-type PTPα cells were treated with IL-1. IP3R1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoblotted with SFKs or c-Src specific antibodies. Time course experiments showed that SFKs associated with IP3R1 after IL-1 and that in particular, c-Src was specifically detected in association with IP3R1 (Fig. 7F). However, this association was dependent on the presence of PTPα, because in PTPα-null cells, the IL-1-induced association of Src with IP3R1 was abolished (Fig. 7F, middle panel). In a similar experimental design, we prepared PTPα immunoprecipitates and immunoblotted for Src and c-Src (Fig. 7G). These data showed that PTPα associates with SFK (and specifically c-Src) in response to IL-1 in a time-dependent manner. Taken together with the earlier data showing that catalytically active PTPα associates with IP3R1 in focal adhesions and ER preparations in response to IL-1 treatment (Fig. 4), we conclude that PTPα may mediate IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling by acting as an adaptor to link IP3R1 to c-Src.

DISCUSSION

Our major finding is that PTPα provides an important structural linkage between focal adhesions and the ER, in part through its interactions with IP3R1 and c-Src. In previous work (46, 58) we found rapid, focal adhesion-dependent release of Ca2+ from the ER in response to IL-1, suggesting a functional relationship between these different organelles, as well as spatial sequestration of signaling molecules involved in Ca2+ signaling (14). In view of these findings, we have sought to define the proteins that mediate this spatial selectivity and that enable focal adhesion restriction of IL-1 signaling.

Src

We found that inhibition of Src kinase activity with SU6656 or PP2 effectively blocked IL-1-induced IP3R1 phosphorylation and ER Ca2+ release, indicating the importance of SFKs in focal adhesion-dependent calcium signaling initiated by IL-1. SFKs are pivotal for integrin-mediated signaling during cell adhesion and spreading because of their kinase-dependent and kinase-independent activities (67). Among the SFKs, c-Src and Fyn are dephosphorylated by PTPα on their inhibitory carboxyl-terminal tyrosine residue, which enhances their kinase activity (31, 54). Consistent with these reports we found that PTPα was essential for enabling signaling downstream of SFKs because PTPα-null cells exhibited very high levels of phosphorylation of the inhibitory Tyr529 residue and showed no IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling. When the inhibitory carboxyl-terminal tyrosine residue was dephosphorylated in cells that have intact focal adhesions and express catalytically active PTPα, SFK catalytic activity enabled direct phosphorylation of IP3R1 and, subsequently, Ca2+ release from the ER. Further, our immunoprecipitation studies showed that c-Src was one of the SFKs that associated with IP3R1, contemporaneous with enhanced ER Ca2+ release. Thus c-Src could be one of the SFKs that directly phosphorylate and activate IP3R1, although other SFKs such as Fyn and Lyn could also be involved in this process (59, 60).

Importantly, the activation of SFK is only achieved in the presence of intact FA and PTPα and is required for the immediate Ca2+ response in cells treated with IL-1. Eventually continued IL-1 treatment longer than 15 min led to the inactivation of Src and this correlated temporally with increased phosphorylation of inhibitory residue (Tyr529) of Src and diminished phosphorylation of PTPα at Tyr789, consistent with the notion that Tyr(P)789 of PTPα is important for regulating Src activation (24, 54).

IP3 Receptors

IP3Rs are Ca2+-permeable channels located on the membranes of organelles with releasable Ca2+ stores (48). Cell surface biotinylation studies have shown that ∼5–14% of total IP3 receptors are localized to the plasma membranes of several cell types (49). We have previously found abundant IP3R1 isoform in the ER of human gingival fibroblasts (58) and in the ER of murine fibroblasts used here. Notably, IP3R1 was also enriched in focal adhesion-associated proteins, suggesting that IP3R1 may link the ER to FAs at specific cellular sites. As a result of the critical importance of IP3 receptors in Ca2+ release from the ER (51) and their central role demonstrated here in IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling, we focused our studies on IP3R as a Ca2+ release channel and as a candidate protein for linking the ER to FAs.

The precise function of IP3R is mediated by the coordinated actions of Ca2+, phosphorylation, and nucleotides. Ca2+ exerts biphasic control over IP3R (68–70): stimulation by positive feedback at physiological concentrations and inhibition at low micromolar [Ca2+] (71, 72). Phosphorylation of IP3R1 increases its sensitivity to Ca2+ conductance at even low IP3 levels (73). We found that IP3R1 was strongly tyrosine-phosphorylated in response to IL-1, particularly at early time periods (prior to 15 min); this phosphorylation diminished rapidly thereafter. Because our immunoprecipitation studies showed temporal correlations between increased IP3R1 phosphorylation and IP3R1 association with SFK and c-Src, it seems likely that SFKs promote Ca2+ signaling not only by phosphorylating and activating phospholipases that generate IP3 but also by directly phosphorylating IP3R (Tyr353) and augmenting Ca2+ channel activity (59, 73). Further, tyrosine phosphorylation renders the IP3R insensitive to rising inhibitory Ca2+ levels (59), which would otherwise inhibit its open probability.

In addition to its role as a Ca2+ channel in the ER membrane, IP3R has been implicated in many adaptor functions because of its association with various phosphatases (51). Further, the association of IP3R with the FA proteins vinculin, α-actinin, and talin (52) suggest that IP3R could interact with other critical focal adhesion signaling molecules. We found here that IL-1 up-regulated the relative abundance of IP3R1 in ER fractions as well as in FA-associated proteins, but this enrichment only occurred in cells expressing catalytically active PTPα. By total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy imaging of subplasma membrane compartments, we observed that PTPα co-localizes with IP3R1. Consistent with these observations, immunoprecipitation and pulldown assays with purified proteins indicated that PTPα associated with IP3R1. However, we found that IP3R1 was not a substrate of PTPα. Instead, SFKs and, in particular, c-Src associated with and likely phosphorylated IP3R in response to IL-1. Notably, the disruption of the enzymatic activity of PTPα impaired the ability of IP3R1 to associate with PTPα and Src. Apparently, the adaptor function of PTPα relies on the integrity of its catalytic domain because only point mutations in the D1 (C433S) and D2 (C723S) domains were required to disrupt IL-1-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1, Ca2+ signaling, and association of IP3R1 with PTPα. Notably, the association of IP3R1 with PTPα in response to IL-1 may mediate physical approximation of FAs with the ER. By this mechanism PTPα may indirectly control IL-1-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and enhancement of IP3R1 Ca2+ channel activity, possibly via the activation of c-Src or Fyn.

We conclude that PTPα plays two essential roles in IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling. First, PTPα dephosphorylates and activates SFKs, in response to integrin stimulation, that are essential for enabling Ca2+ release through IP3 receptors in the ER. Second, PTPα provides a critical structural link between FAs and the ER as a result of its interactions with IP3R1 and c-Src. This trimolecular interaction is needed for IL-1-induced Ca2+ release.

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating grant (to G. P. D. and C. A. M.).

- IL

- interleukin

- PTP

- protein-tyrosine phosphatase

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FA

- focal adhesion

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- IP3R

- IP3 receptor

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- siRNA

- short interfering RNA

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- PIPES

- 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid

- FN

- fibronectin

- PL

- poly-l-lysine

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- SFK

- src family kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Neill L. A., Dinarello C. A. (2000) Immunol. Today 21, 206–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunne A., O'Neill L. A. (2003) Sci. STKE 2003, re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasse P., Mary C., Guenon I., Noulin N., Charron S., Schnyder-Candrian S., Schnyder B., Akira S., Quesniaux V. F., Lagente V., Ryffel B., Couillin I. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3786–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dayer J. M. (2003) Rheumatology 42, ( Suppl. 2) ii3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle D. L., Han Z., Rutter J. L., Brinckerhoff C. E., Firestein G. S. (1997) Arthritis Rheum. 40, 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graves D. T., Cochran D. (2003) J. Periodontol. 74, 391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagarasan M. O., Aiello F., Muegge K., Durum S., Axelrod J. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7871–7874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid Q. A., Reddy P. J., Tewari M., Uematsu S., Tuncay O. C., Tewari D. S. (2000) Cytokine 12, 1609–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumkumian G. K., Lafyatis R., Remmers E. F., Case J. P., Kim S. J., Wilder R. L. (1989) J. Immunol. 143, 833–837 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caron J. P., Tardif G., Martel-Pelletier J., DiBattista J. A., Geng C., Pelletier J. P. (1996) Am. J. Vet. Res. 57, 1631–1634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reunanen N., Westermarck J., Hakkinen L., Holmstrom T. H., Elo I., Eriksson J. E., Kahari V. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5137–5145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo Y. Y., Luo L., McCulloch C. A., Cruz T. F. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7059–7065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q., Downey G. P., Choi C., Kapus A., McCulloch C. A. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 1898–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo L., Cruz T., McCulloch C. (1997) Biochem. J. 324, 653–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aplin A. E., Juliano R. L. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 695–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrington T. P., Johnson G. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burridge K., Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. (1996) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 463–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidel-Bar R., Cohen M., Addadi L., Geiger B. (2004) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchner J., Kam Z., Tzur G., Bershadsky A. D., Geiger B. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 975–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilic D., Furuta Y., Kanazawa S., Takeda N., Sobue K., Nakatsuji N., Nomura S., Fujimoto J., Okada M., Yamamoto T. (1995) Nature 377, 539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klinghoffer R. A., Sachsenmaier C., Cooper J. A., Soriano P. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 2459–2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harder K. W., Moller N. P., Peacock J. W., Jirik F. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31890–31900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammers R., Lerch M. M., Ullrich A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3391–3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen M., Chen S. C., Pallen C. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11972–11980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlessinger J. (2000) Cell 100, 293–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q., Downey G. P., Herrera-Abreu M. T., Kapus A., McCulloch C. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8397–8406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostman A., Bohmer F. D. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlessinger J. (2000) Cell 103, 211–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carragher N. O., Frame M. C. (2004) Trends Cell Biol. 14, 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng X. M., Wang Y., Pallen C. J. (1992) Nature 359, 336–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.den Hertog J., Pals C. E., Peppelenbosch M. P., Tertoolen L. G., de Laat S. W., Kruijer W. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 3789–3798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoker A. W. (2005) J. Endocrinol. 185, 19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L., Dixon J. E. (2000) Semin. Immunol. 12, 75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serra-Pages C., Kedersha N. L., Fazikas L., Medley Q., Debant A., Streuli M. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 2827–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng L. P., Wang X., Yu Q. (1999) Genes Cells 4, 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sap J., D'Eustachio P., Givol D., Schlessinger J. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 6112–6116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim K. L., Lai D. S., Kalousek M. B., Wang Y., Pallen C. J. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 245, 693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y., Pallen C. J. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 3231–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons J. T. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 1409–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponniah S., Wang D. Z., Lim K. L., Pallen C. J. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 535–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su J., Muranjan M., Sap J. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacaresse N., Moller B., Danielsen E. M., Okada M., Sap J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35815–35824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng L., Si X., Yu W. P., Le H. T., Ng K. P., Teng R. M., Ryan K., Wang D. Z., Ponniah S., Pallen C. J. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160, 137–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrera Abreu M. T., Penton P. C., Kwok V., Vachon E., Shalloway D., Vidali L., Lee W., McCulloch C. A., Downey G. P. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C931–C944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Wichert G., Jiang G., Kostic A., De Vos K., Sap J., Sheetz M. P. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q., Downey G. P., Bajenova E., Abreu M., Kapus A., McCulloch C. A. (2005) FASEB J. 19, 837–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berridge M. J., Lipp P., Bootman M. D. (2000) Nat. Rev. 1, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan A. A., Steiner J. P., Klein M. G., Schneider M. F., Snyder S. H. (1992) Science 257, 815–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanimura A., Tojyo Y., Turner R. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27488–27493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khan A. A., Steiner J. P., Snyder S. H. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 2849–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patterson R. L., Boehning D., Snyder S. H. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 437–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugiyama T., Matsuda Y., Mikoshiba K. (2000) FEBS Lett. 466, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCulloch C. A., Downey G. P., El-Gabalawy H. (2006) Nat. Rev. 5, 864–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng X. M., Resnick R. J., Shalloway D. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 964–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plopper G., Ingber D. E. (1993) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 193, 571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oakes S. A., Scorrano L., Opferman J. T., Bassik M. C., Nishino M., Pozzan T., Korsmeyer S. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 105–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arora P. D., Ma J., Min W., Cruz T., McCulloch C. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6042–6049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Q., Herrera Abreu M. T., Siminovitch K., Downey G. P., McCulloch C. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31093–31105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jayaraman T., Ondrias K., Ondriasova E., Marks A. R. (1996) Science 272, 1492–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yokoyama K., Su Ih I. H., Tezuka T., Yasuda T., Mikoshiba K., Tarakhovsky A., Yamamoto T. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhandari V., Lim K. L., Pallen C. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8691–8698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roskoski R., Jr. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roskoski R., Jr. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 1155–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang T. S., Tu H., Wang Z., Bezprozvanny I. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 403–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pieper A. A., Brat D. J., O'Hearn E., Krug D. K., Kaplin A. I., Takahashi K., Greenberg J. H., Ginty D., Molliver M. E., Snyder S. H. (2001) Neuroscience 102, 433–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edwards A., Pallone T. L. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293, F1518–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaplan K. B., Swedlow J. R., Morgan D. O., Varmus H. E. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1505–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bezprozvanny I., Watras J., Ehrlich B. E. (1991) Nature 351, 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finch E. A., Augustine G. J. (1998) Nature 396, 753–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miyakawa T., Mizushima A., Hirose K., Yamazawa T., Bezprozvanny I., Kurosaki T., Iino M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1674–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boehning D., Joseph S. K., Mak D. O., Foskett J. K. (2001) Biophys. J. 81, 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mak D. O., McBride S., Foskett J. K. (2001) J. Gen. Physiol. 117, 435–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cui J., Matkovich S. J., deSouza N., Li S., Rosemblit N., Marks A. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16311–16316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]