Abstract

Efficient turnover of unnecessary and misfolded RNAs is critical for maintaining the integrity and function of the mitochondria. The mitochondrial RNA degradosome of budding yeast (mtEXO) has been recently studied and characterized; yet no RNA degradation machinery has been identified in the mammalian mitochondria. In this communication, we demonstrated that purified human SUV3 (suppressor of Var1 3) dimer and polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) trimer form a 330-kDa heteropentamer that is capable of efficiently degrading double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates in the presence of ATP, a task the individual components cannot perform separately. The configuration of this complex is similar to that of the core complex of the E. coli RNA degradosome lacking RNase E but very different from that of the yeast mtEXO. The hSUV3-hPNPase complex prefers substrates containing a 3′ overhang and degrades the RNA in a 3′-to-5′ directionality. Deleting a short stretch of amino acids (positions 510–514) compromises the ability of hSUV3 to form a stable complex with hPNPase to degrade dsRNA substrates but does not affect its helicase activity. Furthermore, two additional hSUV3 mutants with abolished helicase activity because of disrupted ATPase or RNA binding activities were able to bind hPNPase. However, the resulting complexes failed to degrade dsRNA, suggesting that an intact helicase activity is essential for the complex to serve as an effective RNA degradosome. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the complex of hSUV3-hPNPase is an integral entity for efficient degradation of structured RNA and may be the long sought RNA-degrading complex in the mammalian mitochondria.

The current opinion on mitochondrial RNA degradation is largely based on our understanding of the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome and the yeast mitochondrial degradosome (mtEXO). The E. coli RNA degradosome consists of four components: RNase E, an endoribonuclease in which the C terminus serves as the scaffold of the multiprotein complex; PNPase,4 an ambivalent enzyme that catalyzes 3′-to-5′ phosphorolysis as well as 5′-to-3′ polymerization of RNA; RhlB, a DEAD-box helicase; and enolase, a glycolytic enzyme (1–7). The 4-MDa multi-enzyme complex has been postulated to have a molar ratio of 4 RNase E:12 PNPase:4 RhlB:8 enolase (2, 4, 5, 8–10). More recently, it has been reported that in the absence of RNase E, RhlB and PNPase can form a 380-kDa complex (2 RhlB:3 PNPase) to degrade dsRNA substrates (11–13). In budding yeast, an ATP-dependent DExH/D-box RNA helicase, Suv3p, and a 3′-to-5′ directed exoribonuclease, Dss1, have been demonstrated to be the essential components of the mtEXO (14). In vitro, the two proteins have been shown to form a heterodimer that is capable of degrading dsRNA substrates containing a 3′ overhang (15). Unlike its counterpart in the E. coli RNA degradosome, Dss1 does not form a trimeric ring structure but belongs to the RNR family of exoribonucleases that are mainly involved in rRNA maturation in the chloroplast of higher plants (16).

In these well studied systems, the RNA-degrading complexes always contain an ATP-dependent RNA helicase to unwind the secondary structures of the RNA, followed by 3′-5′ degradation by an exoribonuclease. This provides a fundamental concept in RNA degradation; once a RNA molecule has been identified and marked for elimination, possibly mediated by 3′ polyadenylation (17, 18), a coordinated process involving secondary structure removal and exoribonucleolytic trimming must take place simultaneously for efficient RNA removal.

Currently, no RNA-degrading complex has been identified in the mammalian mitochondria, mainly because the key components of the E. coli RNA degradosome and the yeast mtEXO do not appear to be evolutionarily conserved. Nevertheless, to maintain its proper function and integrity, the mammalian mitochondria need a mechanism to efficiently remove unnecessary and/or misfolded RNA transcripts. In the search for the RNA-degrading complex in the human mitochondria, the human homologues of the key components of the E. coli RNA degradosome and the yeast mtEXO were examined. It was found that both SUV3 and PNPase not only have human homologues but also contain an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence and localize primarily in the mitochondria (19, 20). We previously reported that purified human SUV3 harbors an ATP-dependent helicase activity for dsRNA, dsDNA, and RNA-DNA hybrids (21). Human PNPase was shown to form a ring trimer structure similar to its counterparts in E. coli and spinach chloroplast and the eukaryotic exosome (18, 22–26) and harbors RNA poly(N)polymerization and phosphorolytic exoribonuclease activities in vitro (18, 22). However, whether these two enzymes work cooperatively in the mammalian mitochondria remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we demonstrated that the purified hSUV3 forms a complex with hPNPase at a 2:3 molar ratio. The resulting 330-kDa heteropentameric complex efficiently degrades dsRNAs containing 3′ overhang in an ATP-dependent manner, a task the individual components cannot perform separately. By detailed binding and mapping assays, a short stretch (amino acids 510–514) of hSUV3 was determined to be critical for hPNPase binding. Deleting these 5 amino acids compromises the ability of hSUV3 to interact with hPNPase to degrade dsRNA. Furthermore, two hSUV3 mutants, K213A and R2 (Δ576–581), that lack ATPase and RNA-binding activities, respectively, were able to form stable complexes with hPNPase. However, the resulting complexes were unable to degrade dsRNA. Together, these results suggest that the complex formed by hSUV3 and hPNPase is an integral entity for efficient degradation of structured RNA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Cloning

Human SUV3 cDNA encoding ΔN46-SUV3 was constructed by deleting the first 46 amino acids and replacing threonine 47 with methionine by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the full-length cDNA as a template. The ΔN46-SUV3 was subsequently subcloned into expression vector pET-19b (Novagen). The expressed protein contains a N-terminal His10 tag and a linker of sequence SSGHIDDDDKHRYPRGGR. The hSUV3 point and deletion mutants mentioned in this paper (K213A, R2, ΔSP2, and ΔSP3) were all constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using pET19b-SUV3ΔN46 as a template. Human PNPase cDNA encoding ΔN46-PNPase was constructed the same way as SUV3 and subcloned into expression vector pET-28b. The expressed protein contains a C-terminal His6 tag and a linker of sequence LQ.

Native Gel Mobility Assay

Purified proteins were run in a 6% glycine-based native gel (pH 10.0) at 200 V for 4 h in Section 10 of Current Protocols in Protein Science (vol. 1) (27).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant hSUV3 and hPNPase

The respective expression vectors were transformed into protein expressing host stain Rosetta. A single colony was grown in suspension at 37 °C overnight with proper antibiotics before inoculating into a 1-liter culture. At an optical density of 1.0, the culture was induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 18 °C for 10 h. All the following steps were performed at 4 °C. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 5× volume of lysis buffer containing 300 mm KCl, 25 mm potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), and 5 mm imidazole supplemented by protease inhibitors: aprotinin, antipain, leupeptin, and pepstain. The cells were broken by sonicating twice for 1 min with a 30-s interval. The cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. Subsequently, 1.5 ml of immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography resin (Bio-Rad) was added to the supernatant and incubated on a rotor for 40 min. The protein-bound immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography was washed extensively by wash buffers containing 25 mm potassium phosphate (pH 8.0), 10 mm imidazole, and increasing concentrations of KCl: 5, 250, and 500 mm. Following elution by elution buffer (25 mm potassium phosphate, pH 8.0, 150 mm imidazole, 250 mm KCl), the protein was further purified by fast protein liquid chromatography (GE Healthcare) with ion exchange chromatography (MonoQ) followed by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200). Fractions containing purified proteins were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in −80 °C.

hSUV3 hPNPase Complex Purification (Complex Formation Assay)

Purified hSUV3 and hPNPase proteins were mixed at various molar ratios and precipitated by ammonium sulfate (0.39 g/ml) to reduce the volume. The protein pellet was resuspended in 0.4 ml of size exclusion chromatography running buffer (25 mm potassium phosphate, pH 8.0, 150 mm KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mm EDTA, 2 mm MgCl2) and incubated on a rotator overnight at 4 °C. The mixture was spun down to remove any precipitation and separated by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200). Fractions of the left-shifted peak were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in −80 °C.

Helicase Substrates

The DNA-RNA hybrid substrates were adopted from Malecki et al. (15). The T20DNA was 5′-radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T7 polynucleotide kinase (Ambion), subsequently purified by G-25 microspin column (GE Healthcare) before annealing with the 3WRNA, 5WRNA, or AntiT-RNA to produce the 3′-OH, 5′-OH, and blunt end helicase substrates, respectively. Their sequences are as follows: T20DNA, 5′-CAAACTCTCTCTCTCTCAAC-3′; 3WRNA, 5′-GUUGAGAGAGAGAGAGUUUGAGAGAGAGAG-3′; 5WRNA, 5′-AGAGAGAGAGGUUGAGAGAGAGAGAGUUUG-3′; and AntiT-RNA, 5′-GUUGAGAGAGAGAGAGUUUG-3′. All of the oligoribonucleotides and oligonucleotides used in this study were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (San Diego, CA).

Helicase Assay

Experimental procedure was adopted from previous publication by Shu et al. (21). With increasing amounts of purified proteins, unwinding reactions were carried out in helicase buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 80 mm KCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 50 ng/μl bovine serum albumin, and 5 mm ATP) containing 40 nm of helicase substrate and 400 nm of unlabeled competing T20DNA strand. The reaction volume and time were 20 μl and 30 min, respectively. The reaction was terminated by adding an equal volume of nondenaturing loading buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mm EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 25% glycerol). The reaction mixtures were separated by native PAGE (15% polyacrylamide, 1× TBE). The reaction products were electrophoresed through 15% polyacrylamide 1× TBE gels, which was dried and quantified using a Storm 320 Phosphor Imager (Molecular Dynamics).

ATPase and Nucleic Acid Binding Assays

Experimental procedures were based on previous publication by Shu et al. (21).

Short ssRNA Substrate

RNA oligonucleotide of sequence 5′-AAACUAAAAAAAAA was 5′-radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T7 polynucleotide kinase (Ambion) and subsequently purified by G-25 microspin column (GE Healthcare).

Short ssRNA Degradation Assay

Similar to the helicase assay, with increasing amounts of purified proteins, RNA degradation reaction was carried out in reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, 80 mm KCl, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm MnCl2, 100 ng/μl bovine serum albumin) containing 100 nm of radiolabeled short ssRNA substrate. The reaction was terminated by adding equal volume of denaturing loading buffer (1× TBE, 82% formamide, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol). the reaction products were electrophoresed through a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 1× TBE, 10% formamide, and 7 m urea, which was dried and quantified the same way as in the helicase assay.

dsRNA Substrates

The 3WRNA and the 5WRNA were 5′-radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T7 polynucleotide kinase (Ambion), subsequently purified by G-25 Microspin column (GE Healthcare) before annealing with the T22RNA of sequence: 5′-CUCAAACUCUCUCUCUCUCAAC-3′ to produce the 3′- and 5′-OH dsRNA substrates, respectively.

dsRNA Degradation Assay

RNA degradation reaction was carried out in reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, 80 mm KCl, 3 mm ATP, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 2.5 mm MnCl2) containing 120 nm of radiolabeled dsRNA substrate. The reaction was terminated by adding an equal volume of denaturing loading buffer (1× TBE, 82% formamide, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol). The reaction products were electrophoresed, dried, and quantified the same way as in the helicase assay.

Analytical Ultracentrifuge Sedimentation Equilibrium Assay

The analytical ultracentrifugation experiments were performed with a Beckman Optima XL-I instrument with an An60Ti rotor. hSUV3 alone, hPNPase alone, and a complex obtained from procedures above were run in the gel filtration running buffer at room temperature. Sedimentation equilibrium was reached after 24 h, and absorbance changes as a function of radial position were determined at 12,000 rpm for the single proteins and 6000 rpm for the complex. The data were analyzed using the Origin software package (Beckman), and the program Sednterp was used to calculate the partial specific volumes and solvent densities of both proteins based on their amino acid sequences.

GST Binding Assay

Experimental procedures were adopted from Zhong et al. (28).

BIAcore Surface Plasmon Resonance Analysis

Experimental methods were adopted from Liou et al.(11). Briefly, the hSUV3-hPNPase interactions were examined in real time by a BIAcore instrument (GE Healthcare). Purified recombinant hPNPase protein was immobilized via amine coupling on a CM5 sensor chip. The interaction assays were performed at room temperature with a constant flow rate of 5 μl/min. 5 μl of purified recombinant hSUV3 WT, ΔSP2, and K213A were injected at concentrations indicated in supplemental Fig. S5. The chemical binding groups were regenerated by sequentially washing the analytes with three pulses of 30 μl of 0.1 m glycine buffer (pH 10.5) at a constant flow rate of 10 μl/min until the background level was attained.

RESULTS

hSUV3 and hPNPase Form a 330-kDa Heteropentameric Complex at a 2:3 Molar Ratio

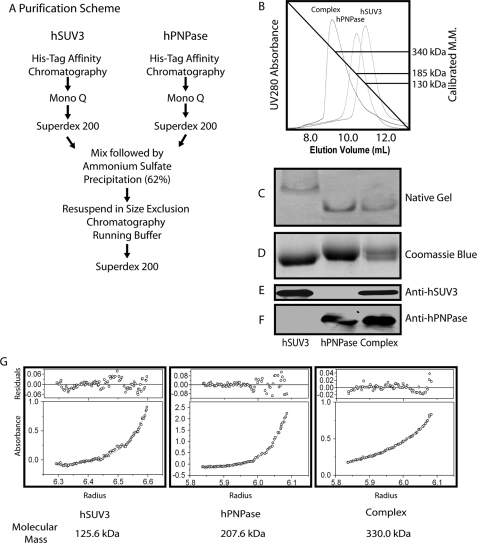

In the E. coli RNA degradosome, RhlB and PNPase form a stable complex at a 2:3 molar ratio (11–13), whereas in budding yeast, the mitochondrial RNA degradosome is a heterodimer consisted of one molecule each of Suv3 and Dss1 (15). Whether human SUV3 and PNPase form a complex like E. coli or yeast warrants investigation. To approach this, the two proteins were first separately purified to homogeneity. As shown in Fig. 1B, based on the empirical molecular masses determined by size exclusion chromatography, hSUV3 and hPNPase exist as a dimer and a trimer, respectively. When mixing hSUV3 and hPNPase at 2:3 ratio (Fig. 1A), the elution profile came out to be a sharp peak with a molecular mass of ∼340 kDa (Fig. 1B). Along with the individual proteins, the potential complex was then subjected to native gel electrophoresis analysis and was found to migrate significantly faster than hSUV3 but slightly slower than hPNPase (Fig. 1C). SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-hSUV3 and anti-hPNPase antibodies confirmed that the complex fraction contains both hSUV3 and hPNPase (Fig. 1, E and F). To precisely determine the subunit stoichiometry of the complex, the purified proteins were subject to sedimentation equilibrium experiments by analytical ultracentrifugation (Fig. 1G). The molecular masses of hSUV3 and hPNPase were determined to be 125.6 and 207.6 kDa, respectively, consistent with the size exclusion chromatography profiles of the respective proteins. The molecular mass of the complex was determined to be 330.0 kDa, which is remarkably close to that of hSUV3 and hPNPase added together. Collectively, these results suggest that hSUV3 and hPNPase form a 330-kDa heteropentamer at a 2:3 molar ratio.

FIGURE 1.

hSUV3 and hPNPase form a 330kDa heteropentameric complex at a 2:3 molar ratio. A, purification scheme of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex. B, size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200) elution profiles for hSUV3, hPNPase, and the hSUV3-hPNPase complex. The numbers to the right are the approximate molecular masses of the purified proteins based on their peak elution volumes. C, native PAGE (6%, pH 10.0) migration pattern of the purified proteins. D, Coomassie Blue staining of the purified proteins in 8% SDS-PAGE. E and F, Western blotting of the purified proteins in 8% SDS-PAGE. G, UV absorbance curves and the calculated molecular masses of the purified proteins determined by equilibrium sedimentation analytical ultracentrifugation.

hSUV3-hPNPase Complex Efficiently Degrades dsRNA Substrates Containing a 3′ Overhang in the Presence of ATP

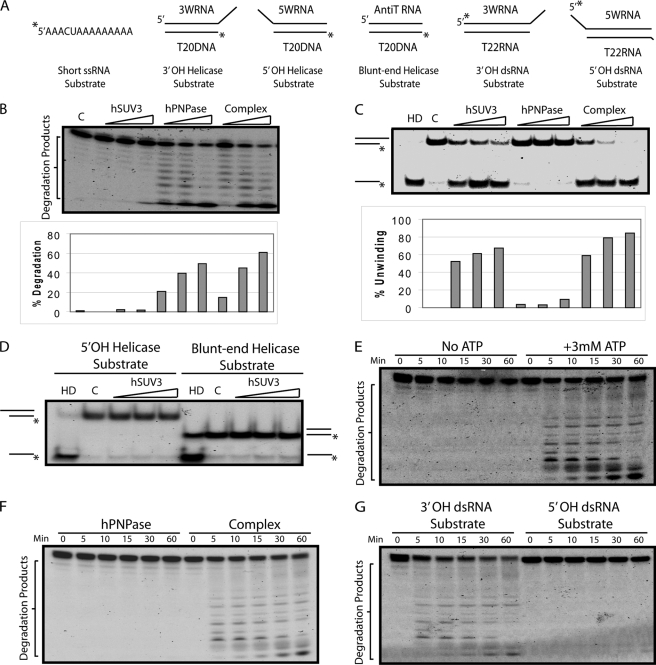

To address the potential cooperativity of this enzyme complex, the enzymatic activities of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex were compared with the individual components using the substrates shown in Fig. 2A. By adding equal molar amounts of the proteins, in the presence of phosphate, hPNPase and the complex appeared to degrade short unstructured ssRNA substrates at a similar rate (Fig. 2B). Consistent with previous reports, the degradation pattern of the reaction products suggests that hPNPase is a 3′-5′ processive exoribonuclease and stops degradation when the RNA substrate is ∼6 nucleotides long (3, 5, 29). Relative to hSUV3, in the absence of phosphate and in the presence of ATP, the complex appeared to have slightly enhanced helicase activity (Fig. 2C). Detailed analysis of the helicase activity of hSUV3 revealed that it has a 3′-to-5′ directionality and prefers substrates with a 3′ overhang over substrates containing a 5′ overhang or a blunt end, which is consistent with the observation made with purified yeast Suv3 (15) (Fig. 2, C and D). When a dsRNA substrate containing an 8-nucleotide 3′ overhang was used to mimic RNAs containing a stable hairpin structure, the complex degraded the longer strand much more efficiently than hPNPase alone in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 2, E and F). Lastly, because both hSUV3 and hPNPase have a 3′-to-5′ directionality, it is no surprise that the complex prefers to degrade dsRNA substrates containing a 3′ overhang to those with a 5′ overhang (Fig. 2G). These results strongly suggest that the hSUV3-hPNPase complex formation is critical for degrading the structured RNA, a task the individual components separately cannot perform.

FIGURE 2.

hSUV3-hPNPase complex efficiently degrades dsRNA substrates containing a 3′ overhang in the presence of ATP. A, nucleic acid substrates used in the in vitro assays. B, increasing amounts of hSUV3, hPNPase, or the hSUV3-hPNPase complex (30, 60, and 120 nm) were incubated with the short ssRNA substrate for 60 min at 37 °C in the presence of 5 mm phosphate. C, increasing amounts of hSUV3, hPNPase, or the hSUV3-hPNPase complex (30, 60, and 120 nm) were incubated with the 3′-OH helicase substrate for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of 5 mm ATP. Lane HD, heat denatured, in which the reaction mix containing the substrate was heated up to 80 °C for 10 min to denature the duplex immediately before loading onto 15% native PAGE. Lane C, control. The size exclusion chromatography buffer containing no protein was added. D, same as C, except the substrates used here are the 5′-OH and the blunt end helicase substrates. E, time course 3′-OH dsRNA substrate degradation activities of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex (120 nm) in the presence of 5 mm phosphate with or without 3 mm ATP. F, time course 3′-OH dsRNA substrate degradation activities of the purified proteins (120 nm) in the presence of 3 mm ATP and 5 mm phosphate. G, time course dsRNA degradation activities of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex using the 3′-OH dsRNA substrate and 5′-OH dsRNA substrate in the presence of 3 mm ATP and 5 mm phosphate.

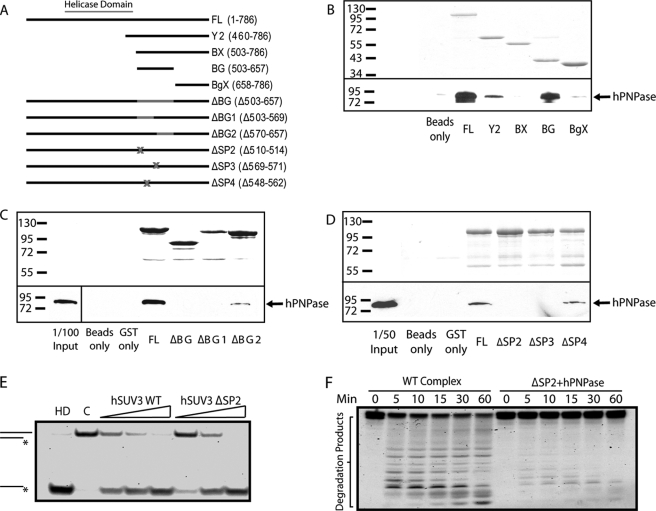

Stable Complex Formation Is Critical for hSUV3 to Interact with PNPase to Degrade Structured RNA

To further substantiate that the complex formation between these two enzymes is critical for its cooperative activity, we generated a series of hSUV3 genetic mutants with the intention to isolate a region that is important for hPNPase interaction but not for the helicase activity. To approach this, we first generated four GST fusion proteins containing different fragments downstream of the hSUV3 helicase domain (Fig. 3A). By incubating purified hPNPase with the GST fusion proteins in the binding assay, we determined that both Y2 (residues 460–786) and BG (residues 503–657) fragments bind to hPNPase, whereas the BgX fragment (residues 658–786) does not (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the hPNPase-interacting region of hSUV3 is likely to be within the BG fragment. To confirm and further narrow down the region of hSUV3 that is important for interaction with hPNPase, three additional constructs with different segments of BG deleted from full-length hSUV3 were made (Fig. 3A). These mutants were designated as ΔBG (residues 503–657), ΔBG1 (residues 503–569), and ΔBG2 (residues 570–657). As shown in Fig. 3C, the BG region is indeed critical for hPNPase binding, because deletion of the entire BG region abolishes hPNPase binding. Deletion of the BG1 region also eliminates hPNPase binding, whereas residual hPNPase was pulled down by ΔBG2, suggesting that a critical binding region is within BG1. However, the BG1 segment is still considerably large (67 amino acids), indicating the need to further narrow down the region essential for hPNPase binding.

FIGURE 3.

Complex formation is critical for hSUV3 to interact with PNPase to degrade structured RNA. A, list of GST-hSUV3 constructs used in the in vitro binding experiments. B–D, the top panels show the Coomassie Blue staining of the input hSUV3 recombinant proteins. The bottom panels show the amount of hPNPase pulled down by the hSUV3 proteins and detected by Western blotting using monoclonal anti-hSUV3 antibody. E, increasing amounts of wild type hSUV3 and ΔSP2 (30, 60, and 120 nm) were incubated with the 3′-OH helicase substrate for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of 5 mm ATP. Lane HD, heat denatured. Lane C, control. F, time course 3′-OH dsRNA substrate degradation activities of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex (120 nm) and a mixture containing hSUV3 ΔSP2 and hPNPase of equivalent molar amounts in the presence 3 mm ATP and 5 mm phosphate.

Based on the presumption that the hSUV3-hPNPase complex formation is critical for the biological function of hSUV3, the binding region for hPNPase must be evolutionally conserved. Therefore, we compared the amino acid sequences of SUV3 across different species to search for the most conserved segments within BG1 (data not shown). We found three short stretches of 5–10 amino acids that are highly conserved and constructed three mutants with deletions in these regions (designated as ΔSP2, ΔSP3, and ΔSP4) (Fig. 3A). Of the three, the ΔSP2 and ΔSP3 mutants showed reduced binding affinity for hPNPase (Fig. 3D). To test whether the mutations in ΔSP2 and ΔSP3 affect the helicase activity of hSUV3, the mutants were subjected to the helicase assay. ΔSP2 mutant exhibited unaffected helicase activity relative to the wild type hSUV3 (Fig. 3E), whereas the ΔSP3 mutant showed significantly reduced helicase activity (supplemental Fig. S1). To test whether ΔSP2 can still form a stable complex with hPNPase, the protein was subject to the complex formation assay (Fig. 1A). When ΔSP2 and hPNPase are mixed at a 2:3 ratio, a higher molecular mass peak does form; however, a much higher proportion of the protein exists in the free form, suggesting that the mutation hinders the complex formation (supplemental Fig. S2). To reaffirm this point, the interactions between hPNPase and hSUV3 WT and ΔSP2 were quantified in real time by surface plasmon resonance analysis using a BIAcore system. With hPNPase immobilized on the CM5 sensing chip and injecting the hSUV3 samples at various concentrations as analytes, the Kd values of hSUV3 WT and ΔSP2 were determined to be 1.38 and 1.64 μm, respectively (supplemental Fig. S5). Consistently, at low concentrations (100 and 180 nm), the amount of residual binding for ΔSP2 was only ∼50% of hSUV3 WT (supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that the ΔSP2 mutation compromises the binding affinity of hSUV3 for hPNPase. Together, these results indicate that we have indeed identified a region (SP2) in hSUV3 that is critical for hPNPase binding but not the helicase activity. We then mixed the ΔSP2 mutant protein and hPNPase to test dsRNA degradation activity in comparison with the wild type complex. As shown in Fig. 3F, the ΔSP2/hPNPase mixture was significantly less effective in degrading the 3′-OH dsRNA substrate relative to the wild type complex, suggesting that a stable complex formation between hSUV3 and hPNPase is critical for efficient dsRNA degradation.

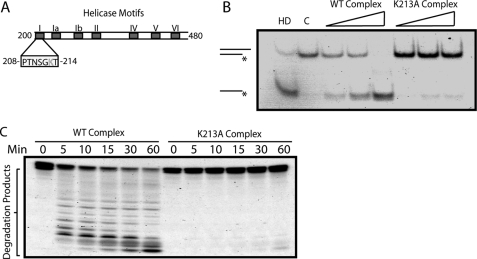

hSUV3 K213A Mutant Forms a Stable Complex with PNPasea but Fails to Degrade dsRNA

Although we have determined that hSUV3 and hPNPase form a complex that degrades dsRNA substrates, the precise contribution of hSUV3 to this process remains unclear. To address this, we first examined whether the helicase activity of hSUV3 serves as an integral component of this process. Previously, it was demonstrated that a lysine to alanine point mutation in the Walker A motif (Motif I) eliminates the ATPase and helicase activity of hSUV3 (Fig. 4A) (30). As determined by the surface plasmon resonance analysis, this mutant has a Kd comparable with that of WT hSUV3 (supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that the point mutation does not alter the binding affinity of hSUV3 to hPNPase. Subsequently, the K213A-hPNPase complex was obtained the same way as described in the complex formation assay (Fig. 1A), in which a sharp peak with a molecular mass of >300 kDa was observed when mixing K213A and hPNPase at a 2:3 ratio (supplemental Fig. S3). However, using this complex for the helicase assay revealed that the K213A-hPNPase complex has greatly reduced helicase activity relative to the wild type hSUV3-hPNPase complex (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the K213A-hPNPase complex degraded the dsRNA substrate much less efficiently relative to the wild type complex (Fig. 4C). These results recapitulate the importance of the helicase activity as an integral component of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex to efficiently degrade dsRNA.

FIGURE 4.

hSUV3 K213A mutant forms a stable complex with PNPase but fails to degrade dsRNA. A, schematic representation of the DExH/D helicase motifs in human SUV3. Walker A domain, or Motif I, has a conserved lysine (Lys213) residue that is critical for ATP binding. B, increasing amounts of wild type hSUV3-hPNPase and K213A-hPNPase complexes (30, 60, and 120 nm) were incubated with the 3′-OH helicase substrate for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of 5 mm ATP. Lane HD, heat denatured. Lane C, control. C, time course 3′-OH dsRNA substrate degradation activities of the purified complexes (120 nm) in the presence of 3 mm ATP and 5 mm phosphate.

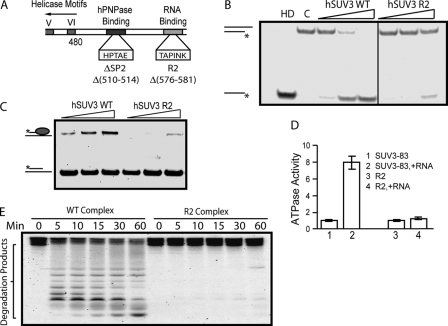

hSUV3 Mutant Depleted of RNA Binding Activity Forms a Complex with hPNPase but Fails to Degrade dsRNA

It appears reasonable that an intact helicase domain (208–480) of hSUV3 is required to facilitate dsRNA degradation by the heteropentameric complex. However, whether the C-terminal half of hSUV3 also plays a role in this coordinated activity is not clear. As previously observed, the ΔSP3 (569–571) mutant, which failed to bind hPNPase, had significantly reduced helicase activity. Thus, it was conjectured that SP3 may be situated in between the hPNPase-binding domain (SP2: 510–514) and a region essential for the helicase activity. Because SP3 is downstream of the hPNPase-binding domain, we looked for a conserved motif downstream of SP3. At positions 576–581, we found a highly conserved sequence, TAPINK (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the mutant protein with these 6 amino acids deleted, R2, showed a loss of helicase activity (Fig. 5B). To address the possibility that this region may be involved in RNA substrate interaction, we performed an RNA binding assay and found that R2 has a significantly lower RNA affinity than the wild type hSUV3 (Fig. 5C). In addition, although the base-line ATPase activity of the R2 deletion mutant was unaffected, adding ssRNA failed to stimulate its ATPase activity (Fig. 5D). This piece of information serves as supporting evidence to suggest that the R2 region is important for RNA binding. Subsequently, the R2 complex was obtained the same way as described in Fig. 1A, in which a sharp peak with a molecular mass of >300 kDa was observed when mixing R2 and hPNPase at a 2:3 ratio (supplemental Fig. S4). Consistent with the failure to bind RNA, the R2 complex has a significantly reduced dsRNA degrading activity relative to the wild type hSUV3-hPNPase complex (Fig. 5E). Together, these results indicate that there is a region toward the C terminus of the helicase domain that is important for RNA binding and hence the helicase activity of hSUV3. Furthermore, the RNA binding activity of hSUV3 is critical for the dsRNA degradation activity of the complex, suggesting that in addition to duplex unwinding, hSUV3 is also in charge of RNA substrate recognition in the complex.

FIGURE 5.

hSUV3 mutant depleted of RNA binding activity forms complex with hPNPase but fails to degrade dsRNA. A, schematic representation of the hPNPase-binding domain and the RNA-binding motif (R2) downstream of the helicase domain. B, increasing amounts of wild type and R2 hSUV3 (30, 60, and 120 nm) were incubated with the 3′-OH helicase substrate for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of 5 mm of ATP. Lane HD, heat denatured. Lane C, control. C, nucleic acid binding assay. Increasing amounts (50, 100, or 200 nm) of wild type hSUV3 or R2 were incubated with 2.0 nm of the partial DNA-RNA duplex. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by 12% native PAGE. A significantly decreased nucleic acid binding was observed for R2 when compared with wild type hSUV3. D, ATPase assay. The R2 retains base-line ATPase activity but fails to respond to RNA stimulation. E, time course 3′-OH dsRNA substrate degradation activities of the purified complexes (120 nm) in the presence of 3 mm ATP and 5 mm phosphate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that hSUV3 and hPNPase form a 330-kDa heteropentameric complex at a 2:3 molar ratio, such that the helicase and exoribonuclease activities of the individual components work in a coordinated manner to degrade dsRNA substrates in the presence of ATP. Structurally, the complex closely resembles an alternative form of the RNA-degrading complex observed in the E. coli system, which the RhlB and PNPase form a 380-kDa complex at a 2:3 ratio (12). In a related study, the region immediately toward the C-terminal of the helicase domain of RhlB was shown to be critical for PNPase binding (11), which is consistent with the ΔSP2 and ΔSP3 mutant studies, supporting the concept that the gross configuration of the RNA degradation machinery is conserved from bacteria to eukaryotic organelles. Judging by the stoichiometry of the respective subunits alone, the mammalian mitochondrial RNA degradosome appears to share a close lineage with the E. coli RNA degradosome. On the other hand, the core complex of the mitochondria degradosome of budding yeast consists of Suv3 and Dss1 at a 1:1 molar ratio. This complex configuration is quite different from that of both E. coli and mammalian mitochondrial degradosome described here. These results suggest that yeast and mammalian cells evolved independently by symbiosis with different bacteria at the fork of the lineage. Interestingly, the predominant form of the E. coli RNA degradosome was shown to contain an endoribonuclease, RNase E, and a glycolytic enzyme, enolase. So far, the counterparts of these two components have not been observed in either yeast or mammalian mitochondrial RNA degrading machineries. Whether RNA degradation in the mammalian mitochondria requires such components remains to be explored.

It has been demonstrated in the E. coli RNA degradosome, the RhlB-PNPase complex, and the budding yeast mtEXO that the cooperative action between a helicase and an exoribonuclease is required to degrade structured RNAs (5, 11, 15). Under physiological conditions, the exoribonuclease alone usually cannot get past stable duplex structures of an RNA substrate and often stalls at the base of the hairpin loop. On the other hand, the helicase alone can unwind the duplex portion of the RNA substrate in the presence of ATP, but the RNA would immediately snap back to the native conformation before a nearby RNase would have the chance to initiate a cleavage. Only when the helicase and exoribonuclease are both present in the same entity can structured RNAs be efficiently degraded. The fact that these enzymatic activities are always harbored in different proteins implies that the individual components may have separate functions by themselves or with other binding partners.

The comprehensive and detailed mechanism of structured RNA degradation by the hSUV3-hPNPase complex cannot be addressed until the structure of the substrate-bound complex is known. However, comparing the contrasting the structural information derived from the RhlB-PNPase and hSUV3-hPNPase complexes provided informative insights on the key steps of the cooperative action. Despite the similarity in subunit stoichiometry, the hSUV3-hPNPase complex employs a highly conserved motif toward the C-terminal of the helicase domain of hSUV3 for RNA substrate binding, which is critical for the ability of the complex to degrade dsRNAs as demonstrated by the R2 mutant. However, this conserved motif is not present in RhlB, indicating different strategies in RNA substrate recognition between the two complexes. Previous studies have implicated that the highly conserved helicase motifs Ia, Ib, V, and VI of DExH/D-box helicases are involved in nucleic acid binding (30) (Figs. 4A and 5A). Hence, it is possible that deleting the R2 region distorted the overall structure of hSUV3, such that these motifs were no longer at their optimal orientation to interact with the RNA substrate. Alternatively, the R2 region could be directly involved in RNA binding. These conjectures can only be resolved when the co-crystal structure of RNA-bound hSUV3-hPNPase complex is available.

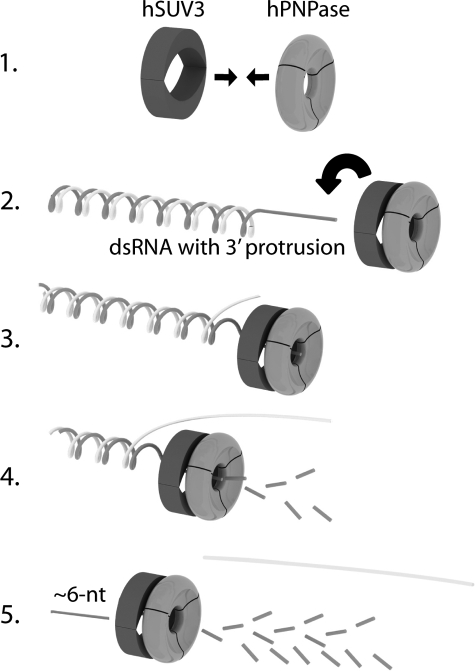

It is intriguing that the R2 motif plays such a critical role in the action of the complex to degrade structured RNA, a process that is likely to begin by the heteropentameric complex binding to the 3′ end of the single-stranded portion of the RNA to be degraded. Although hPNPase also has intrinsic RNA binding affinity (13), because the R2/hPNPase complex cannot degrade dsRNA substrates, hSUV3 appears to be in charge of substrate recognition for the complex. Subsequently, the complex slides along the single-stranded track toward the 5′ end of the RNA with hSUV3 leading hPNPase. When a duplex region is reached, hSUV3 unwinds the double strand in the presence of ATP to allow the hPNPase to degrade the exposed single strand exoribonucleolytically until the RNA is roughly 6 nucleotides long, as proposed in Fig. 6. It is possible that these short ssRNA strands are removed by another RNase; yet so far such a species has not been identified in the mammalian mitochondrion. The RNA substrate shown in the diagram is similar to the one used in the dsRNA degradation assay. By the same mechanism, hSUV3-hPNPase complex can also degrade long RNAs containing hairpin structures, which may more closely reflect the endogenous substrates of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex inside the mitochondria. In addition, as observed in the E. coli RNA degradosome, for efficient degradation, the long structured RNA may need to be first cleaved into smaller segments by an endoribonuclease to expose the 3′ ends for further degradation by the exoribonuclease and helicase. Whether RNA degradation in the mammalian mitochondria requires such an endoribonuclease remains to be elucidated.

FIGURE 6.

Model for dsRNA degradation by the hSUV3 hPNPase complex. The assembly of the heteropentameric complex takes place first (Step 1), followed by loading of the complex onto the single-stranded portion of the dsRNA substrate (Step 2). The complex then moves along the ssRNA track toward the 5′ with hSUV3 leading hPNPase. When a duplex region is reached, hSUV3 unwinds the double strand in the presence of ATP to allow the complex to degrade the exposed single strand exoribonucleolytically (Steps 3 and 4) until the RNA is degraded to roughly 6 nucleotides long (Step 5).

The presence of truncated and polyadenylated mtRNA transcripts inside the human mitochondria has been recently demonstrated (18). Although low in abundance, these internally polyadenylated RNA transcripts exist for every mitochondrially encoded gene. It has been hypothesized that accumulations of these aberrant RNAs may lead to impaired mitochondrial function such as protein synthesis. Recent RNAi knockdown studies suggest that the hSUV3-hPNPase complex may be involved in removing these aberrant truncated RNA species in the mammalian mitochondria in that truncated polyadenylated mtRNA species accumulated in mammalian cells lacking hSUV3 (31). Consequently, the expression levels of Complexes I, III, and IV plunged, leading to impaired OXPHOS and ATP production, increased superoxide production, and cellular senescence and death. Consistently, yeast strains lacking Suv3p exhibit an accumulation of the excised form of the group I intron ω of the mitochondrial 21 S rRNA exons and precursors of 21 S rRNA and VAR1 (14, 32).

On the other hand, it was reported that hPNPase depletion by RNAi silencing did not affect the steady state level of mtRNAs (33, 34). However, in these studies, only the levels of full-length mtRNAs were quantified, and it is possible that knocking down hPNPase caused an accumulation of truncated RNA transcripts. Incidentally, the cellular phenotypes of knocking down hPNPase were strikingly similar to what was observed in hSUV3 RNAi silenced cells. hPNPase knockdown cell lines exhibit impaired OXPHOS and ATP production and slowed cellular growth, which can be explained by increased cellular senescence and death. The observation that steady state levels of the full-length mtRNA transcripts did not change in hPNPase knockdown cells suggests full-length mtRNA degradation may be mediated by a different mechanism.

It is noted that the short aberrant mitochondrial RNA transcripts observed in the hSUV3 knockdown experiments are structurally analogous to the nonstop mRNAs transcripts seen in bacteria and the eukaryotic nucleus and cytoplasm, where RNA surveillance is more thoroughly studied (35–37). In eubacteria, the recognition, disassembly, and decay of the nonstop RNA transcript and the stalled peptide requires the interplay of alanyl-tRNA synthetase, small protein B, elongation factor Tu, and SsrA RNA, a unique species having properties of both tRNA and mRNA (38–41). The tRNA-like portion of the SsrA RNA first empties the A site of the ribosome, and the mRNA-like portion displaces the nonstop mRNA. The precise mechanism that leads to the degradation of the nonstop RNA transcript is not clear, but a recent study showed that it is mediated by the SsrA RNA (42). Evidence suggests that eukaryotes utilize a different strategy to remove nonstop RNA transcripts. As shown in budding yeast, the mRNA surveillance mechanism to remove nonstop transcripts involves the ribosome stalling at the poly(A) tail and being recognized by a cytoplasmic GTPase, Ski7p, which in turn recruits the exosome and the Ski complex to degrade the transcript in a 3′-to-5′ direction (43–45). If the mammalian mitochondria were to use a similar mechanism in removing the aberrant RNA species, it is likely that the hSUV3-hPNPase complex would be recruited to the 3′ end of the RNA transcript as a result of the ribosome stalling at the poly(A) tail before a valid stop codon was reached.

Recently, protease-protection studies suggested that the majority of mammalian PNPase is localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, where no RNA has been reported to be present (33, 46). Based on the observation, it was proposed that human PNPase is not directly involved in RNA degradation inside the mitochondrial matrix. However, due to the limitations of the protease protection assays in detecting protein submitochondrial localizations, one cannot exclude the possibility that trace amounts of hPNPase reside in the mitochondrial matrix to participate directly in the surveillance and processing of mtRNA transcripts. In fact, matrix localization of human PNPase has been implicated in two recent studies, where hPNPase is found to associate with the mtDNA nucleoid located at the inner membrane in the matrix (47, 48). Incidentally, in the same studies, hSUV3 was also identified to be one of the mtDNA nucleoid-associating proteins. Since transcription and translation are tightly coupled inside the mitochondria (49–52), it is no surprise that hPNPase and hSUV3, which are shown in this study to be integral components of the mitochondrial RNA-degrading complex, would be found in close proximity to the mitochondrial genome. Furthermore, by reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation experiments, our preliminary data suggest that a small portion of SUV3 and PNPase interact with each other in vivo (data not shown). It is conceivable that a RNA-degrading complex would be tightly regulated and is only active when needed to prevent a futile cycle. One way to do this is to keep hSUV3 and hPNPase separately localized in the matrix and intermembrane space, respectively. When misfolded or truncated RNAs are present, hPNPase would translocate into the matrix to form a complex with hSUV3 to remove the unwanted RNAs. Elucidating the regulation and control of the hSUV3-hPNPase complex formation in vivo will allow us to understand how the RNA degrading machinery serves to maintain the integrity and physiological functions of the mammalian mitochondrion, a topic that is currently being actively investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Chi-fen Chen for making the GST fusion hSUV3 expression constructs, Dr. Erin Goldblatt for proofreading the manuscript, and Yi Hsuan Lin for helping with the graphics.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AG027877 (to W. H. L.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- PNPase

- polynucleotide phosphorylase

- dsRNA

- double-stranded RNA

- ssRNA

- single-stranded RNA

- h

- human

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- WT

- wild type

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- OH

- overhang.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grunberg-Manago M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Genet. 33, 193–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpousis A. J., Van Houwe G., Ehretsmann C., Krisch H. M. (1994) Cell 76, 889–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Py B., Causton H., Mudd E. A., Higgins C. F. (1994) Mol. Microbiol. 14, 717–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpousis A. J. (2007) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 71–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Py B., Higgins C. F., Krisch H. M., Carpousis A. J. (1996) Nature 381, 169–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miczak A., Kaberdin V. R., Wei C. L., Lin-Chao S. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 3865–3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohanty B. K., Kushner S. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11966–11971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blum E., Py B., Carpousis A. J., Higgins C. F. (1997) Mol. Microbiol. 26, 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehretsmann C. P., Carpousis A. J., Krisch H. M. (1992) Genes Dev. 6, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callaghan A. J., Marcaida M. J., Stead J. A., McDowall K. J., Scott W. G., Luisi B. F. (2005) Nature 437, 1187–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liou G. G., Chang H. Y., Lin C. S., Lin-Chao S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41157–41162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin P. H., Lin-Chao S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16590–16595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin-Chao S., Chiou N. T., Schuster G. (2007) J. Biomed. Sci. 14, 523–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dziembowski A., Piwowarski J., Hoser R., Minczuk M., Dmochowska A., Siep M., van der Spek H., Grivell L., Stepien P. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1603–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malecki M., Jedrzejczak R., Stepien P. P., Golik P. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dziembowski A., Malewicz M., Minczuk M., Golik P., Dmochowska A., Stepien P. P. (1998) Mol. Gen. Genet. 260, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slomovic S., Portnoy V., Yehudai-Resheff S., Bronshtein E., Schuster G. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1779, 247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slomovic S., Laufer D., Geiger D., Schuster G. (2005) Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 6427–6435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piwowarski J., Grzechnik P., Dziembowski A., Dmochowska A., Minczuk M., Stepien P. P. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 329, 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minczuk M., Piwowarski J., Papworth M. A., Awiszus K., Schalinski S., Dziembowski A., Dmochowska A., Bartnik E., Tokatlidis K., Stepien P. P., Borowski P. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5074–5086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shu Z., Vijayakumar S., Chen C. F., Chen P. L., Lee W. H. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 4781–4790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portnoy V., Palnizky G., Yehudai-Resheff S., Glaser F., Schuster G. (2008) RNA 14, 297–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar D., Fisher P. B. (2006) Pharmacol. Ther. 112, 243–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blum E., Carpousis A. J., Higgins C. F. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4009–4016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yehudai-Resheff S., Hirsh M., Schuster G. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 5408–5416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yehudai-Resheff S., Portnoy V., Yogev S., Adir N., Schuster G. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 2003–2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coligan J. E., Dunn Ben M., Ploegh Hidde L., Speicher David W., Wingfield Paul T. (1995) Current Protocols in Protein Science, Unit 10.3, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhong Q., Chen C. F., Li S., Chen Y., Wang C. C., Xiao J., Chen P. L., Sharp Z. D., Lee W. H. (1999) Science 285, 747–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Symmons M. F., Williams M. G., Luisi B. F., Jones G. H., Carpousis A. J. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cordin O., Banroques J., Tanner N. K., Linder P. (2006) Gene 367, 17–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khidr L., Wu G., Davila A., Procaccio V., Wallace D., Lee W. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27064–27073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margossian S. P., Li H., Zassenhaus H. P., Butow R. A. (1996) Cell 84, 199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen H. W., Rainey R. N., Balatoni C. E., Dawson D. W., Troke J. J., Wasiak S., Hong J. S., McBride H. M., Koehler C. M., Teitell M. A., French S. W. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 8475–8487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagaike T., Suzuki T., Katoh T., Ueda T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19721–19727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vanacova S., Stefl R. (2007) EMBO Rep. 8, 651–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West S., Gromak N., Norbury C. J., Proudfoot N. J. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houseley J., LaCava J., Tollervey D. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abo T., Inada T., Ogawa K., Aiba H. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3762–3769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muto A., Ushida C., Himeno H. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karzai A. W., Roche E. D., Sauer R. T. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akimitsu N. (2008) J. Biochem. 143, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto Y., Sunohara T., Jojima K., Inada T., Aiba H. (2003) RNA 9, 408–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Hoof A., Frischmeyer P. A., Dietz H. C., Parker R. (2002) Science 295, 2262–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frischmeyer P. A., van Hoof A., O'Donnell K., Guerrerio A. L., Parker R., Dietz H. C. (2002) Science 295, 2258–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner E., Lykke-Andersen J. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 3033–3038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H. W., Koehler C. M., Teitell M. A. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 600–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y., Bogenhagen D. F. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25791–25802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bogenhagen D. F., Rousseau D., Burke S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3665–3675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aloni Y., Attardi G. (1971) J. Mol. Biol. 55, 251–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aloni Y., Attardi G. (1971) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 68, 1757–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ojala D. K., Montoya J., Attardi G. (1980) Nature 287, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ojala D., Montoya J., Attardi G. (1981) Nature 290, 470–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.