Abstract

Aldosterone increases renal tubular Na+ absorption in large part by increasing transcription of the epithelial Na+ channel α-subunit (α-ENaC) expressed in the apical membrane of collecting duct principal cells. We recently reported that a complex containing the histone H3K79 methyltransferase disruptor of telomeric silencing-1 (Dot1) associates with and represses the α-ENaC promoter in mouse inner medullary collecting duct mIMCD3 cells, and that aldosterone acts to disrupt this complex and its inhibitory effects (Zhang, W., Xia, X., Reisenauer, M. R., Rieg, T., Lang, F., Kuhl, D., Vallon, V., and Kone, B. C. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 773–783). Here we demonstrate that the NAD+-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) functionally and physically interacts with Dot1 to enhance the distributive activity of Dot1 on H3K79 methylation and thereby represses α-ENaC transcription in mIMCD3 cells. Sirt1 overexpression inhibited basal α-ENaC mRNA expression and α-ENaC promoter activity, surprisingly in a deacetylase-independent manner. The ability of Sirt1 to inhibit α-ENaC transcription was retained in a truncated Sirt1 construct expressing only its N-terminal domain. Conversely, Sirt1 knockdown enhanced α-ENaC mRNA levels and α-ENaC promoter activity, and inhibited global H3K79 methylation, particularly H3K79 trimethylation, in chromatin associated with the α-ENaC promoter. Sirt1 and Dot1 co-immunoprecipitated from mIMCD3 cells and colocalized in the nucleus. Sirt1 immunoprecipitated from chromatin associated with regions of the α-ENaC promoter known to associate with Dot1. Aldosterone inhibited Sirt1 association at two of these regions, as well as Sirt1 mRNA expression, in a coordinate manner with induction of α-ENaC transcription. Overexpressed Sirt1 inhibited aldosterone induction of α-ENaC transcription independent of effects on mineralocorticoid receptor trans-activation. These data identify Sirt1 as a novel modulator of α-ENaC, Dot1, and the aldosterone signaling pathway.

Epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC)2 is composed of three genetically distinct subunits (α, β, and γ), and is expressed in the apical membrane of salt-absorbing epithelia of kidney, colon, and lung (1). ENaC expressed in the distal nephron constitutes the rate-limiting step for renal Na+ and fluid reabsorption and therefore is essential for physiological control of blood pressure and electrolyte composition. Genetic disorders of ENaC activity, such as pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 and Liddle syndrome, are characterized by hypotension and hypertension, respectively (2). The number of channels present at the plasma membrane is highly regulated through channel biosynthesis and delivery to the plasma membrane and by channel retrieval from the plasma membrane (4–6). Of the three ENaC subunits, it is synthesis of α-ENaC subunits that appears to be rate-limiting for the formation of new ENaC multimers. Thus mechanisms controlling α-ENaC gene transcription are central to the understanding of channel biosynthesis.

Aldosterone, a key regulator of epithelial Na+ absorption, induces transepithelial Na+ transport in the collecting duct in large part through activation of α-ENaC gene transcription. Aldosterone administration or secondary hyperaldosteronism caused by salt restriction enhances α-ENaC gene transcription without increasing β or γ subunit expression or altering α-ENaC mRNA turnover (3). The biological actions of aldosterone on target gene transcription have generally been believed to be mediated principally or exclusively through the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family. Aldosterone has both immediate (<3 h) effects on ENaC, attributed to increased trafficking or activity of ENaC in the apical membrane, and delayed actions (>3 h) that involve the synthesis of new ENaC subunits (1, 2, 15, 18, 33). A highly conserved imperfect glucocorticoid-response element (GRE) has been identified in the 5′-flanking regions of the human, mouse, and rat α-ENaC genes and found to be necessary for trans-activation (12, 17, 35). Although heterologous expression of human α-ENaC in murine M1 collecting duct cells suggests that increased α-ENaC expression alone may be insufficient to increase ENaC activity under basal conditions, increased α-ENaC expression does appear to be necessary for full aldosterone induction of ENaC function (4).

In prior work, we identified in the mouse inner medullary collecting duct cell line mIMCD3 a novel aldosterone-sensitive nuclear repressor complex, comprised of Dot1 and Af9 (5). Under basal conditions, this complex associates with chromatin, and Dot1 hypermethylates histone H3K79 associated with four specific regions of the α-ENaC 5′-flanking region, thereby repressing α-ENaC transcription (6–8). Aldosterone inhibited Dot1 and Af9 expression and their interaction, leading to hypomethylation of histone H3K79 at specific regions of the α-ENaC 5′-flanking region and release of the basal transcriptional repression of α-ENaC (7, 8). We further determined that Dot1, like α-ENaC, was expressed in collecting duct principal cells (6).

Dot1 was originally identified as a gene affecting telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (9), and it is distinguished from other histone lysine methyltransferases by the absence of a Su(var)3–9, Enhancer-of-zeste, Trithorax (SET) domain, and by the fact that it introduces multiple methyl groups on H3K79 via a “distributive” (also termed “nonprocessive”) kinetic mechanism (10). Dot1 can methylate 3 methyl groups of Lys-79 in the core domain of histone H3, so that monomethylated (H3K79me1), dimethylated (H3K79me2), and trimethylated (H3K79me3) forms of H3K79 can be observed in chromatin (11, 12). In contrast to the independent generation of multiple methylation states via a processive mechanism, the lower methylation states catalyzed by Dot1 are necessary transient intermediates for the synthesis of higher methylation states. Thus, the relative abundance of the methylation states is expected to depend on Dot1 activity, and the global H3K79 methylation appears to be functionally more important than a specific H3K79 methylation state in yeast (10). Indeed, functional roles of the different methylated states or of particular patterns of H3K79me1, H3K79me2, and H3K79me3 have yet to be demonstrated.

Sirtuins comprise the family of Sir2 orthologs in mammals. Of the seven human sirtuins, Sirt1 is most similar to the yeast Sir2 protein (13, 14). Sirt1 functions as a class III histone deacetylase, binding NAD+ and acetyllysine within protein targets and generating lysine, 2′-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose, and nicotinamide as enzymatic products. Nicotinamide, by promoting a base-exchange reaction at the expense of deacetylation, serves as a noncompetitive inhibitor of Sirt1 (15). Sirt1 is a modular protein with three partially characterized domains that contain putative or experimentally confirmed motifs. The N-terminal domain (amino acids 1–210) includes a nuclear localization signal (16) and multiple phosphorylation motifs. The central region (amino acids 210–500) contains a conserved catalytic domain for deacetylation (17), and a C-terminal region that may be regulated by phosphorylation (18, 19). Through its deacetylase activity, Sirt1 regulates diverse biological processes, including gene silencing, stress resistance, metabolism, differentiation, and aging (20). In vitro, Sirt1 preferentially deacetylates histones H4K16 and H3K9, interacts with and deacetylates histone H1 at Lys-26, and contributes to heterochromatin formation (21). In addition, more than a dozen nonhistone proteins, including transcription factors and transcriptional coregulatory proteins, serve as substrates for Sirt1 (22). However, no previous study has implicated sirtuins in aldosterone signaling or the regulation of a membrane transport protein, and deacetylase-independent actions of Sirt1 on biological processes have not been fully explored.

Given the well described functional interplay in gene silencing between Sir proteins and Dot1 in yeast (23), we hypothesized that Sirt1 might participate in chromatin modifications important for the Dot1-mediated repression of α-ENaC gene transcription in murine collecting duct cells. Here, we report that Sirt1 is indeed expressed along with α-ENaC in collecting duct cells, forms an aldosterone-sensitive complex with Dot1 in chromatin associated with specific regions of the α-ENaC promoter that results in global H3K79 hypermethylation, and also serves to suppress α-ENaC gene transcription. Surprisingly, however, we found that these effects of Sirt1 are independent of its deacetylase activity and apparently do not involve Af9 interactions. These results disclose novel actions of Sirt1, a physical and functional interaction of Sirt1 and Dot1, and detail further complexity in the regulation of epithelial Na+ transport and aldosterone signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Plasmids

LipofectamineTM 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), aldosterone (Sigma), spironolactone (Sigma), nicotinamide (Sigma), and the Dual Luciferase kit (Promega) were purchased and used according to the manufacturer's instructions. An antibody directed against enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was from Clontech. Antibodies directed against murine Sirt1, acetylated or total histone H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, and H4K16 were from Cell Signaling, and antibodies directed against H3K79me1, H3K79me2, and H3K79me3 were from Abeam. The plasmids EGFP-Dot1a, FLAG-Af9, and pGL3Zeocin-1.3α-ENaC-Luc (termed α-ENaC-Luc) have been described (6). pGRE-Luc, a plasmid containing a 4× GRE concatamer coupled to a TATA box upstream of the firefly luciferase gene, was purchased from Stratagene. The murine Sirt1 cDNA was purchased from Upstate. The deacetylase-deficient murine Sirt1 mutant plasmid pcDNA3.1-Sirt1(H355Y) was constructed by using a PCR-directed mutagenesis method (Stratagene). RFP-tagged murine Sirt1 fusion protein (pRFP-Sirt1) was constructed by cloning the Sirt1 cDNA into the XhoI site of pDsRed-monomer-C1 (Clontech). DNA encoding the N-terminal (amino acids 1–240) and central (amino acids 210–500) domains of Sirt1 were cloned into pcDNA3.1 to generate expression plasmids pSirt1-(1–240) and pSirt1-(210–500). The authentic expression of these mutant Sirt1 proteins was verified by immunoblotting of extracts of transiently transfected mIMCD3 cells. All inserts in the constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture, Aldosterone Treatment, Transient and Stable Transfections, and RNA Interference

mIMCD3 cell culture, aldosterone treatment, and transient transfections using the LipofectamineTM 2000 reagent were performed as described (8). Briefly, cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 plus 10% fetal bovine serum. Before adding 1 μm aldosterone or 0.01% ethanol as vehicle control at different time points, the cell medium was changed to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum for at least 24 h. All cells were then harvested at the same time point. To knockdown Sirt1 mRNA levels by RNA interference, murine Sirt1 ON-TARGETplus SMARTPOOL siRNA or the negative control siRNA (Dharmacon) was transiently transfected into mIMCD3 cells using the DharmaFECT transfection reagent. The efficiency of silencing Sirt1 expression was measured by quantitative RT-PCR and determined by comparison to RNA harvested from cells transfected with the negative control plasmid.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA of mIMCD3 cells was purified using the miniRNA kit plus DNase I treatment (Qiagen). The cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification were then carried out using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad), and primers specific for Sirt11, α-ENaC, or β-actin (used as a reference standard) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The copy number of Sirt1 or α-ENaC transcripts was normalized to that of β-actin from the same sample. The sequences of all primers are available from the authors upon request. Their specificity was analyzed by agarose gel and melting curve analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as we previously described (8). Briefly, whole cell lysates of HEK 293 cells transfected with an empty vector, pEGFP-Dot1, or pFLAG-Af9 were prepared by using low-salt lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol). After preclearing with IgG plus protein A/G-Sepharose beads, the lysates were incubated with anti-Sirt1 antibody, anti-Af9 antibody, or isotype control IgG at 4 °C for 4 h on a rotator, and then the protein A/G-Sepharose beads were added to the lysates for an additional 1 h rotation at 4 °C. The beads were washed 6 times with low salt lysis buffer, and the precipitates were eluted with sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and further analyzed by immunoblot with antibody against EGFP or FLAG to detect immunoreactivity for Dot1 and Af9, respectively.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

mIMCD3 cells grown on glass coverslips were transiently co-transfected with pEGFP-Dot1 and pRFP-Sirt1. The cells were then fixed in buffered 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. After 3 washes in phosphate-buffered saline, slides were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-diphenylindole, mounted with UltraCruz Mounting medium (Santa Cruz) and visualized. Sections were examined under a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM, 510 UV; Carl Zeiss). Images were acquired with a Plan-Neofluor ×40 (numerical aperture = 0.75) objective and evaluated with Zeiss LSM 510 imaging software including three-dimensional reconstruction.

ChIP-qPCR Assays

ChIP and ChIP-qPCR assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Upstate) and as previously described (8). The eluted DNA fragments were purified to serve as templates for qPCR with primers constructed to amplify the regions Ra (−1327/−965), R0 (−988/−713), R1 (−735/−415), R2 (−414/+80), and R3 (−57/+494) from α-ENaC. qPCRs were run in triplicate and the values were transferred into copy numbers of DNA using a standard curve of genomic DNA with known copy numbers. The resulting transcription values were then normalized for primer pair amplification efficiency using the qPCR values obtained with input DNA.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± S.D. Unpaired Student's t test was performed and significance was set at p < 0.05. All experiments were replicated a minimum of three times, with each independent observation representing a single n in the figure legends. The duplicates or triplicates in RT-qPCR or qPCR experiments were counted as a single n because they were derived from a single sample, and their average was used to represent the corresponding sample to calculate the final average and standard deviation, which were further normalized to the control as indicated in the figure legend.

RESULTS

Sirt1 Represses Basal α-ENaC Promoter Activity and Endogenous mRNA Expression in mIMCD3 Cells

To test whether Sirt1 regulates basal α-ENaC transcription, we manipulated the Sirt1 expression level and then measured the effects on endogenous α-ENaC mRNA expression, and, in separate experiments, on the activity of an α-ENaC promoter-Luc construct stably incorporated in mIMCD3 cells. mIMCD3 cells exhibit many of the phenotypic properties of the IMCD in vivo, and contain all of the components of the Dot1, Af9, Sgk1, and aldosterone signaling pathways.

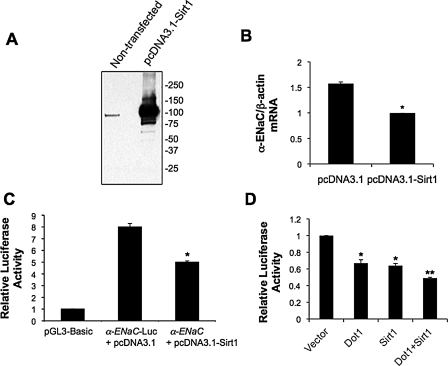

As seen in the representative immunoblot (Fig. 1A), robust Sirt1 overexpression was achieved by transient transfection and resulted in ∼35–40% lower endogenous α-ENaC mRNA expression (Fig. 1B) and α-ENaC promoter-Luc activity (Fig. 1C). To determine whether the inhibitory effect of Sirt1 was partially synergistic or additive with that of Dot1, co-transfection experiments were performed. Co-transfection of Dot1 with Sirt1 resulted in greater inhibition of α-ENaC promoter-Luc activity compared with transfection of either encoding DNA alone, suggesting functional interplay of the two proteins (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Overexpressed Sirt1 down-regulates basal α-ENaC mRNA expression and α-ENaC promoter activity in collecting duct cells. A, representative immunoblot showing expression of endogenous Sirt1 in mIMCD3 cells, and Sirt1 overexpression by transient transfection of mIMCD3 with pcDNA3.1-Sirt1. B, qRT-PCR showing that transient overexpression of Sirt1 inhibits the expression of endogenous α-ENaC mRNA in mIMCD3 cells. β-Actin levels were invariant under the different conditions. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus pcDNA3.1-transfected cells. C, luciferase assay demonstrating that transient Sirt1 overexpression suppresses basal expression of a stably incorporated α-ENaC promoter-luciferase construct (α-ENaC-Luc) in mIMCD3 cells. The cells were transiently transfected with empty vector pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-Sirt1 along with the Renilla luciferase reporter pRL-SV40 as an internal control. The firefly luciferase activity of each sample was normalized to its Renilla luciferase activity to generate the “relative luciferase activity.” The relative luciferase activity of the vector-transfected cells was designated as 1 and utilized to determine the relative level and the significance of the other samples. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of five independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus corresponding values for α-ENaC-Luc + pcDNA3.1. D, luciferase assay demonstrating that co-overexpression of Sirt1 and Dot1 repress luciferase activity in mIMCD3 cell stable lines expressing the α-ENaC promoter-luciferase minigene to a greater degree than individual overexpression of Sirt1 or Dot1 (α-ENaC-Luc). Data are the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments each performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 versus vector; **, p < 0.05 versus Dot1 or Sirt1.

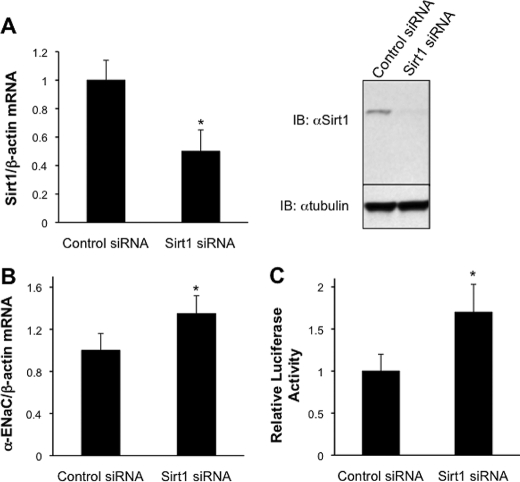

In reciprocal experiments, Sirt1 knockdown was accomplished by RNA interference. qRT-PCR determinations indicated that Sirt1 mRNA expression in Sirt1 siRNA-transfected cells was ∼50% less than in cells transfected with the control siRNA (Fig. 2A), and this was accompanied by a substantial decrease in Sirt1 protein expression (Fig. 2A). Transfection of Sirt1 siRNA resulted in ∼40% greater levels of endogenous α-ENaC mRNA compared with controls (Fig. 2B). Transfection of the stable cell lines expressing α-ENaC promoter-Luc with the Sirt1 siRNA resulted in a nearly 2-fold increase in basal promoter activity (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

siRNA knockdown of Sirt1 up-regulates basal α-ENaC mRNA expression and α-ENaC promoter activity in collecting duct cells. A, qRT-PCR analysis (left) and representative immunoblot (IB) (right) demonstrating RNA interference-mediated knockdown of Sirt1 expression in mIMCD3 cells. Cells were transfected with a scrambled control siRNA or a Sirt1-specific siRNA. qRT-PCR data are mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 versus control siRNA, n = 5. B, qRT-PCR showing that siRNA knockdown of Sirt1 augments the expression of endogenous α-ENaC mRNA. mIMCD3 cells were transfected as in A. *, p < 0.05 versus control siRNA, n = 4. C, luciferase assay in mIMCD3 cell stable lines expressing the α-ENaC promoter-luciferase minigene (α-ENaC-Luc) that had been transiently transfected with control or Sirt1-specific siRNAs. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control siRNA.

Sirt1 Co-immunoprecipitates and Colocalizes with Dot1

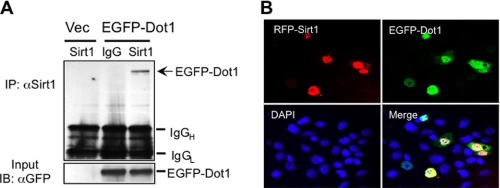

We previously established that Dot1 and Af9 co-immunoprecipitate from mouse kidney lysates (6–8). To determine whether endogenous Sirt1 interacts with Dot1, co-immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-Sirt1 antibody or isotype control IgG were performed in HEK 293 cells that had been transiently transfected with EGFP-Dot1a. HEK 293 cells were used as host cells because of their high efficiency of transient transfection and because they are kidney epithelial cells. The precipitated immune complex was further analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-EGFP antibody to identify Dot1 in the complex. As shown in Fig. 3A, EGFP-Dot1 was immunoprecipitated by the anti-Sirt1 antibody but not with nonimmune IgG. Similar experiments were performed with overexpression of FLAG-Af9, and subsequent co-immunoprecipitation with anti-Sirt1 antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. However, Af9 immunoreactivity was not detected in the immunoprecipitates under these conditions (not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Sirt1 associates and colocalizes with Dot1. A, pEGFP-Dot1 or empty vector (Vec) was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells, and 36 h later, the cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Sirt1 antibody or isotype control IgG. The precipitated immune complex was further analyzed by immunoblot (IB) with anti-EGFP to determine the expression level of Dot1. The blot is representative of three independent experiments (IgGH, IgG heavy chain; IgGL, IgG light chain). B, pRFP-Sirt1 and pEGFP-Dot1 were transiently co-transfected into mIMCD3 cells. Cells were fixed 24 h after transfection, and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to localize nuclei. The expression and intracellular localization of red (Sirt1) and green (Dot1) fluorescence-tagged proteins were examined by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Magnification, ×40.

We attempted glutathione S-transferase pulldown assays with Sirt1 and Dot1 fusion proteins, but we could not consistently generate the full-length Sirt1 fusion protein, presumably because of its size. Moreover, using fragments of the two proteins, we did not reproducibly detect binding. This negative result could mean that the conformations of the full-length proteins are important for the interaction, or that the two proteins do not directly interact, but do so through a bridging protein.

Sirt1 has been shown to reside in the cytoplasm and nucleus depending on the cell type. We previously demonstrated that Dot1 and Af9 colocalize in the nucleus when their epitope-tagged coding DNAs are cotransfected in HEK 293 cells (6–8). We sought to determine whether Sirt1 is also expressed in the nucleus of mIMCD3 cells. EGFP-Dot1 was co-expressed with RFP-tagged Sirt1 by transient transfection, and the expressed proteins analyzed by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. In these studies, EGFP-Dot1 was used, because the available Dot1 antibodies were not suitable for immunolocalization studies. As shown in Fig. 3B, EGFP-Dot1 and RFP-tagged Sirt1 displayed exclusively nuclear co-localization. The neighboring, unsuccessfully transfected cells, identified by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) staining of their nuclei, showed no fluorescence for either protein (Fig. 3B).

Sirt1 Knockdown Inhibits Distributive Histone H3 Lys-79 Methylation in Chromatin at α-ENaC Promoter Subregions

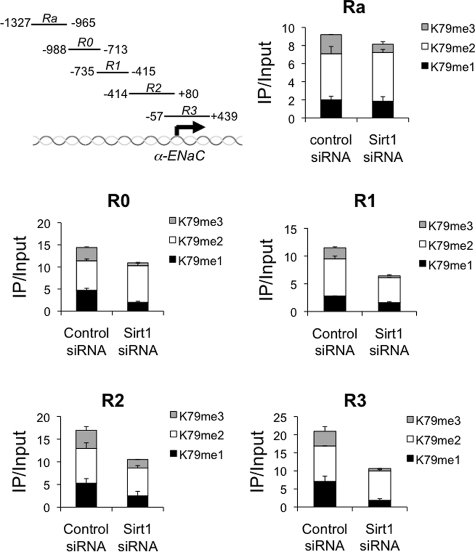

Previously, we demonstrated in ChIP assays with an antibody directed against H3 K79me2 that Dot1 bound under basal conditions to each of 5 partially overlapping subregions (Ra, −1327/−965; R0, −988/−713; R1, −735/−415; R2, −414/+80; and R3, −57/+494) spanning the 1.3-kb α-ENaC 5′-flanking region in mIMCD3 cells (Fig. 4), and that this was correlated with histone H3K79me2 hypermethylation at these sites (7, 8). In those studies, we did not investigate other H3K79 methylation states. Moreover, Af9 and Sgk1 were associated with the R0–R3 subregions, but not Ra under basal conditions (7, 8). Similarly, overexpression of Dot1 promoted hypermethylation of histone H3 K79me2 at R0, R1, and R3, but not at R2 (7, 8). In contrast, overexpressed Af9 promoted H3K79me2 at each of the R0–R3 subregions (7, 8). Thus the Ra subregion (binds Dot1 but not Af9) and the R2 subregion (H3K79me2 hypermethylated by overexpressed Af9 but not Dot1) exhibit distinctive associations with the two proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Sirt1 knockdown inhibits distributive H3K79 methylation in mIMCD3 cell chromatin associated with subregions of the α-ENaC 5′-flanking region. The subregions are schematized in the top left panel. mIMCD3 cells were transfected with a scrambled control siRNA or a Sirt1-specific siRNA. ChIP-qPCR analysis of mono- (K79me1), di- (K79me2), and tri-methylated (K79me3) H3K79 in mIMCD3 cells was then performed. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 4).

We hypothesized that Sirt1 amplifies the distributive activity of Dot1 on H3K79 methylation and thereby contributes to basal repression of α-ENaC transcription. siRNA knockdown of Sirt1 expression, therefore, would result in global H3K79 hypomethylation and a relative decrease in the proportion of H3K79me3. Accordingly, we performed ChIP-qPCR assays with antibodies directed against H3K79me1, H3K79me2, and H3K79me3 for each of the 5 subregions of the α-ENaC promoter in mIMCD3 cells that had been transfected with control siRNA or Sirt1 siRNA. To compare the control and Sirt1 knockdown cells in this analysis, we took the sum of the different methylation states to represent the global H3K79 methylation, and then calculated the proportion of the total represented by H3K79me1, H3K79me2, and H3K79me3 in each condition.

In the control siRNA cells, all 3 methylation states of H3K79 were detected in all 5 subregions (Fig. 4). At the Ra, R0, R1, and R2 subregions, the proportions of the three methylation states were relatively comparable, with the greatest proportion being H3K79me2, yet a substantial proportion (∼20%) existed as H3K79me1 and H3K79me3. At the R3 subregion, H3K79me2 was the least abundant of the 3 methylation states, and the proportions of H3K79me1 and H3K79me3 were relatively equal (Fig. 4). Thus, under basal conditions, the pattern of H3K79 hypermethylation marks on chromatin associated with the α-ENaC promoter appear to be relatively uniform and to include substantial proportions of all H3K79 methylation states (Fig. 4).

Consistent with our hypothesis, mIMCD3 cells transfected with the Sirt1 siRNA exhibited 25–50% lower global H3K79 methylation (indicated by the total value of the summed bars in Fig. 4) at each of the 5 subregions compared with the controls. The most dramatic reductions in global H3K79 methylation were at the R1 and R3 subregions, which also were the only subregions to exhibit reductions in the abundance of all three H3K79 methylation states (Fig. 4). For all of the subregions, H3K79me3 was the most affected of the methylation states; it was 50% lower at R2, and negligible at all the other subregions (Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the idea that Sirt1 basally supports the high level, distributive H3K79 methyltransferase activity of Dot1 in chromatin associated with the α-ENaC promoter, and that this effect appeared to be greatest at the R1 and R3 subregions.

The Inhibitory Effect of Sirt1 on α-ENaC Transcription Is Independent of Sirt1 Deacetylase Activity

The ability of Sirt1 to alter the function of target proteins has consistently been ascribed to its deacetylase activity or from ADP-ribosylation resulting from this biochemical reaction. To determine whether Sirt1 deacetylase activity is required for the inhibitory effects on α-ENaC transcription, a deacetylase-defective Sirt1 mutant was constructed (H355Y) and used in transfection studies in the mIMCD3 cells stably expressing α-ENaC-Luc. The Sirt1H355Y mutant protein contains a substitution of tyrosine for the invariant catalytically active histidine at amino acid residue 355, and has been characterized (24).

As independent validation of the efficacy of the mutation to eliminate the deacetylase activity of Sirt1, we tested the ability of wild type Sirt1 and Sirt1H355Y to deacetylate p53, a well characterized substrate of Sirt1 (24). mIMCD3 cells were treated with the Class I and II histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A to allow acetylation of p53. Wild type Sirt1 and Sirt1H355Y were then transfected into the cells and the levels of acetylated and total p53 were tested by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 5A, trichostatin A-treated cells exhibited robust acetylation of p53, which was significantly abrogated by transfection with wild type Sirt1, but not Sirt1H355Y. This result established in vivo that overexpressed wild type Sirt1 can deacetylate a representative substrate in mIMCD3 cells and that the Sirt1H355Y mutant is indeed incompetent to deacetylate target substrate.

FIGURE 5.

Deacetylase independence of Sirt1-mediated inhibition of α-ENaC transcription in mIMCD3 cells. A, representative (n = 3) immunoblot showing that trichostatin A (TSA) treatment of mIMCD3 cells resulted in robust acetylation of p53, and that this was significantly abrogated by transfection with wild type Sirt1, but not the deacetylase-dead Sirt1H355Y mutant. This result established in vivo that the Sirt1H355Y mutant is indeed incompetent to deacetylate target substrate. B, the effects of transfection of Sirt1H355Y on the activity of an α-ENaC promoter-luciferase minigene stably integrated into the mIMCD3 cell genome was compared with that of wild type Sirt1 in the presence of vehicle or 1 μm aldosterone. *, p < 0.05 versus corresponding α-ENaC-Luc control, n = 4. C, nicotinamide, which inhibits both the deacetylase and ADP-ribosyltransferase activities of Sirt1, does not alter the ability of Sirt1 to inhibit α-ENaC-Luc activity. mIMCD3 cell lines expressing a stably incorporated α-ENaC promoter-Luc minigene were treated with or without 5 mm nicotinamide in the presence or absence of 1 μm aldosterone for 7 h. α-ENaC-Luc activity was then measured. Data are mean ± S.D., n = 4. D, luciferase activity (means ± S.D.) was measured in the stable α-ENaC promoter-Luc mIMCD3 cells that had been transiently transfected with empty vector or expression plasmids encoding full-length Sirt1, amino acids 1–240 of Sirt1, or amino acids 210–500 of Sirt1, and then treated with vehicle or aldosterone for 24 h. The value for the vector-transfected, vehicle-treated samples was set as 1 and utilized to determine the relative level and the significance of the other samples. *, p < 0.05 versus corresponding vector control, n = 4. The diagram above the graph depicts the protein domain structure of murine Sirt1.

Surprisingly, overexpression of Sirt1H355Y led to inhibition of α-ENaC-Luc activity under basal as well as aldosterone-induced conditions that was indistinguishable from that obtained by transfection of wild type Sirt1 (Fig. 5B). Similarly, nicotinamide, which is a product of Sirt1-mediated deacetylation and is used as a noncompetitive inhibitor of this reaction mechanism, did not alter the inhibitory effect of Sirt1 on α-ENaC-Luc activity in vehicle or aldosterone-treated mIMCD3 cells (Fig. 5C). Finally, we did not detect any differences in the acetylation of known Sirt1 target histones H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, or H4K16 in immunoblots of bulk histones isolated from mIMCD3 cells that had been treated in the presence or absence of 5 mm nicotinamide or 1 μm aldosterone (to inhibit Sirt1 deacetylase activity or expression, respectively), nor did we detect acetylation of Dot1 in co-immunoprecipitation/immunoblot experiments (data not shown).

Finally, we compared the ability of Sirt1 mutants encoding only the N-terminal domain (pSirt1-(1–240)) or only the central catalytic domain (pSirt1-(210–500)) to the ability of full-length Sirt1 to inhibit basal and aldosterone-induced activity of α-ENaC-Luc in the mIMCD3 cells stably expressing α-ENaC-Luc. Immunoblotting was used to monitor the level of the overexpressed Sirt1 fragment relative to the endogenous full-length Sirt1 (data not shown). As seen in Fig. 5D, Sirt1-(1–240) inhibited basal α-ENaC-Luc activity to nearly the same degree as the full-length construct under both treatment conditions, whereas Sirt1-(210–500) was without effect. These data confirm that the Sirt1 inhibitory effect is deacetylase-independent.

Aldosterone Down-regulates Sirt1 Expression and Sirt1 Association with Specific Subregions of the α-ENaC Promoter in Vivo

In the α-ENaC promoter-Luc cell lines, aldosterone induced α-ENaC promoter-Luc activity beginning at ∼3 h, increasing almost exponentially thereafter, and reaching ∼5-fold at 24 h compared with α-ENaC promoter-Luc cells treated with vehicle (Fig. 6A). 24 h duration of aldosterone exposure was selected for subsequent promoter activity experiments in the stable cell lines expressing α-ENaC promoter-Luc. Our prior work showed that aldosterone inhibited Dot1 mRNA expression in mIMCD3 cells at 2 h of treatment and H3K79me2 methylation at 7 h (6). In the present study, qRT-PCR was used to measure expression of Sirt1 and α-ENaC mRNAs from the same RNA samples, at the same time points, in response to aldosterone. Aldosterone down-regulated Sirt1 mRNA expression within 1 h, and this occurred coordinately with an increase in α-ENaC expression (Fig. 6B). For both Sirt1 and α-ENaC, the level of mRNA change induced by aldosterone was sustained for at least 24 h, the longest treatment duration studied. Sirt1 protein expression was down-regulated to a similar extent over the time course studied (Fig. 6B, bottom). We did not observe a significant difference in α-ENaC promoter-Luc activity in cells that were transfected with control siRNA versus Sirt1 siRNA (data not shown). This result may indicate a threshold effect: because aldosterone down-regulates Sirt1 mRNA expression by about 30%, further knockdown of Sirt1 expression (to 50%) may not produce a further dose-response change. This hypothesis will need to be more rigorously tested.

FIGURE 6.

Aldosterone down-regulates Sirt1 mRNA expression and its association with chromatin at the α-ENaC promoter as it up-regulates α-ENaC promoter activity and endogenous α-ENaC mRNA expression. A, luciferase assay demonstrating time course of aldosterone-induced expression of a stably incorporated α-ENaC promoter-luciferase construct in mIMCD3 cells. The mIMCD3 cell lines harboring stably transfected pGL3Zeocin-1.3α-ENaC (α-ENaC-Luc) or its empty parent vector (pGL3-Basic) were grown in charcoal-stripped serum for 24 h, and then treated with or without aldosterone (1 μm) or vehicle for the indicated times. The relative luciferase activity of the vector-transfected cells was designated as 1 and utilized to determine the relative level and the significance of the other samples. *, p < 0.05 versus α-ENaC-Luc, n = 5. B, time course experiments showing the effects of treatment with 1 μm aldosterone for the indicated intervals on the expression of Sirt1 and α-ENaC mRNAs in mIMCD3 cells. The mRNAs for the two genes were measured from the same samples by qRT-PCR. *, p < 0.05 versus time = 0, n = 6. The representative immunoblot (IB) (n = 3), probed first with anti-Sirt1 antibody and then with anti-α-tubulin antibody as a loading and housekeeping reference, shows a similar down-regulation with aldosterone treatment. The Sirt1/tubulin ratio represents the results of scanning densitometry of the blots. C, aldosterone down-regulates Sirt1 association with specific regions of the α-ENaC promoter in vivo. mIMCD3 cells were treated with vehicle or 1 μm aldosterone for the indicated time periods, and ChIP assays were performed with anti-Sirt1 antibody or nonimmune IgG and primer sets designed to amplify sequential subregions of the α-ENaC 5′-flanking region (see Fig. 4). Representative (n = 3) agarose gels of the final PCR products are shown. IP, immunoprecipitation.

We also previously reported that aldosterone dramatically inhibited H3K79me2 specifically at the R0, R1, and R3 subregions, but not R2 (7, 8). We tested the hypotheses in the current study that Sirt1 associates in vivo with chromatin at these same subregions, and that aldosterone disrupts this association. We used ChIP assays to monitor the changes of Sirt1 in these regions and their response to different durations of aldosterone treatment. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-Sirt1 antibody or non-immune IgG from mIMCD3 cells. The DNA in the precipitated immune complex was then analyzed by PCR with primers designed to amplify α-ENaC promoter subregions corresponding to each subregion (Fig. 7C). Unfortunately, we could not identify a condition in which the signal to background was adequate for analysis of ChIP results with the anti-Sirt1 antibody of the R3 subregion. Accordingly, we restricted our analysis to the Ra, R0, R1, and R2 subregions.

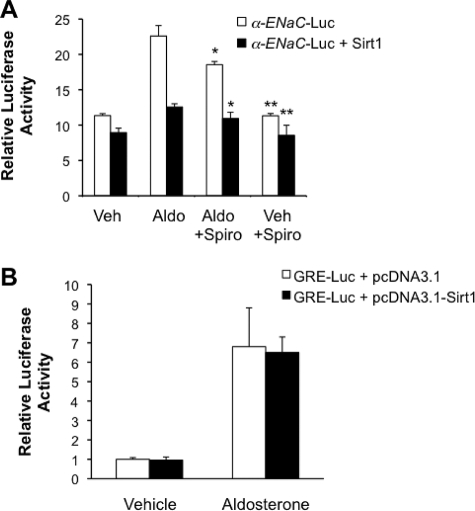

FIGURE 7.

MR independence of Sirt1 inhibition of aldosterone-induced α-ENaC transcription in mIMCD3 cells. A, the effect of transfection of Sirt1 on the activity of an α-ENaC promoter-luciferase minigene (α-ENaC-Luc) stably integrated into the mIMCD3 cell genome was measured in the presence and absence of vehicle, 1 μm aldosterone (Aldo), and/or 1 μm spironolactone as indicated. *, p < 0.05 versus corresponding aldosterone-treated α-ENaC promoter-luc control; **, p < 0.05 versus corresponding aldosterone-treated α-ENaC-Luc+pcDNA3.1-Sirt1, n = 6. B, Sirt1 overexpression does not affect the aldosterone (Aldo) (1 μm) inducibility of a co-transfected GRE-luciferase construct (GRE-Luc) in mIMCD3 cells. n = 4.

Under basal conditions (time 0), chromatin-associated Sirt1 was detected in all four subregions of the α-ENaC promoter examined, but not in the complex precipitated by isotype IgG control (Fig. 6C). This pattern is identical to that of Dot1 and H3K79me2, but differs from that of Af9, which we had shown did not exhibit significant association with the Ra subregion. In cells treated with aldosterone, however, the amount of Sirt1 immunoprecipitated with the DNA of the R0 and R1 subregions was lower at 2.5 h and much less at 5 h of aldosterone treatment compared with time 0, whereas levels of Sirt1 associated with the Ra and R2 regions were unaffected (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that Sirt1 associates with chromatin at the α-ENaC promoter at all of the regions known to harbor Dot1 under basal conditions and to be associated with H3K79 methylation (Fig. 4), and that like Dot1, aldosterone down-regulates its association specifically with the α-ENaC R0 and R1 subregions.

The Inhibitory Effect of Sirt1 on Aldosterone-induced α-ENaC Transcription Is Largely Independent of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor

Aldosterone induction of α-ENaC gene expression is known to be mediated by MR-dependent and -independent pathways. We used the MR antagonist spironolactone to determine the MR dependence of the inhibitory effects of Sirt1 on α-ENaC-Luc activity. Dose-response experiments, over a range of 10−8 to 10−4 m spironolactone, indicated that inhibition of aldosterone (1 μm)-stimulated α-ENaC-Luc activity required 1 μm spironolactone, and that this concentration provided maximal inhibition (∼30%) over the range tested (data not shown). Accordingly, we selected 1 μm spironolactone for use in further studies. As shown in Fig. 7A, aldosterone induced an ∼2-fold increase in α-ENaC-Luc activity in cells treated with the vehicle (ethanol) for spironolactone. Spironolactone (1 μm) treatment reduced this aldosterone induction to ∼1.5-fold. Cells transfected with Sirt1 and treated with the vehicle for spironolactone exhibited only a ∼50% increase in aldosterone-stimulated α-ENaC-Luc activity. In contrast, Sirt1 overexpressing cells treated with spironolactone yielded essentially no aldosterone induction of α-ENaC-Luc activity. These results indicate that Sirt1 effects its inhibition via a mechanism(s) independent from the MR antagonist, and that the Sirt1-dependent component of inhibition appears to be greater than that of MR.

To be confident that the spironolactone-independent effects of Sirt1 were not the result of a generalized disruption of the aldosterone-MR-GRE signaling pathway, we used cotransfection of a GRE-luciferase reporter plasmid to interrogate the pathway in cells cotransfected with empty vector or Sirt1. As expected, aldosterone strongly induced GRE-Luc activity; however, this induction was not affected by Sirt1 overexpression (Fig. 7B). Taken with the pharmacological data, these results indicate that Sirt1 exerts its inhibitory effect on aldosterone-induced α-ENaC promoter activity in largely MR-independent, and possibly gene-specific manner.

DISCUSSION

In the present report, we demonstrate a previously unrecognized functional and physical interaction between Dot1 and Sirt1 that results in global H3K79 hypermethylation in chromatin along the α-ENaC 5′-flanking region and inhibition of α-ENaC gene transcription. This effect appears to be mediated by an action of Sirt1 to support the distributive methyltransferase activity of Dot1 on H3K79 methylation, but, surprisingly is not mediated by Sirt1 deacetylase activity. We also determined that Sirt1 inhibits aldosterone-induced α-ENaC gene transcription via a pathway that is largely independent of MR. To our knowledge, these results also provide the first example of a functional effect of Sirt1 to regulate a protein that does not serve as a substrate for its deacetylase or ADP-ribosylase activities, and for deacetylase-dependent (with p53 as target) and -independent effects of Sirt1 to occur in the same cell type. These results raise the possibility that, in some cases, the actual interaction of Sirt1 with other proteins may be more important than its catalytic activity.

Functional and Physical Interaction of Dot1 and Sirt1

Sirt1 has been shown to interact with more than a dozen proteins in vitro and in vivo, including transcription factors p53 (24, 25), FOXO family proteins (26), NF-κB (27), and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (28), and coregulatory proteins such as p300 (29), but all of these have also served as substrates for Sirt1 enzymatic activity. Sirt1 also acts as a repressor of glucocorticoid induction of ucp3 gene expression, effecting histone deacetylation in the ucp3 promoter. This repressor effect involves a specific disruption of the association of p300 with the glucocorticoid receptor (30). Indeed, we observed that overexpression of Sirt1 in mIMCD3 cells resulted in deacetylation of acetylated p53 (Fig. 5A), a well recognized substrate of Sirt1 (24, 25). However, the fact that (a) we saw no difference in the inhibitory capacity of a deacetylase-dead Sirt1 mutant (Fig. 6B) or of Sirt1-(1–240) (Fig. 5D) on α-ENaC promoter activity, (b) overexpression of the Sirt1 catalytic domain did not reproduce the inhibitory effect of the full-length protein (Fig. 5D), and (c) nicotinamide did not inhibit the Sirt1-mediated effects on α-ENaC promoter activity (Fig. 5C) indicates that neither the deacetylase activity nor the ADP-ribosylase activity of Sirt1 was involved in the inhibitory effect of Sirt1 on α-ENaC promoter activity. The possibility that the Dot1 interaction somehow inactivates the deacetylase activity of Sirt1 remains to be formally tested. For example, an endogenous nuclear protein termed active regulator of SIRT1 is expressed in human kidney and other tissues and is known to interact with the N-terminal domain of Sirt1 in glutathione S-transferase pulldown assays (31). Perhaps the interaction of Dot1 with Sirt1 inhibits active regulator of Sirt1 binding or activity.

The fact that coexpression of Sirt1 and Dot1 yielded a greater inhibitory effect on α-ENaC promoter activity than expression of either protein alone (Fig. 1D) suggests that Sirt1 and Dot1 have partially additive, independent inhibitory effects (with that of Sirt1 being presently unknown) on α-ENaC transcription, or that Sirt1 association with Dot1 amplifies or sustains the latters methyltransferase activity in chromatin, and hence its repression of α-ENaC transcription. We favor the latter model given the fact that Sirt1 knockdown was associated with global H3K79 hypomethylation and near loss of H3K79me3 compared with controls in our ChIP-qPCR assays of the α-ENaC promoter (Fig. 4). A caveat with our approach is that it does not measure unmethylated H3K79, although based on other systems (10), this is likely to be very low.

Exactly how Sirt1 affects catalysis of Dot1 in this setting is unclear. Sirt1 could affect the chromatin substrate to make H3K79 more accessible for interaction with Dot1. Differences in other chromatin modifications associated with the α-ENaC promoter, for example, might explain the marked variation in the degree of Sirt1-mediated effects on H3K79 methylation along the α-ENaC promoter, which were most prominent at the R1 and R3 subregions (Fig. 4). Alternatively, Sirt1 could facilitate H2B monoubiquitination of Dot1 and therefore its overall catalytic activity (32). Finally, Sirt1 could directly affect the active site of Dot1. There is precedent in yeast for protein interactions influencing Dot1 activity: interactions of Dot1 with the N-terminal tail of histone H4 (33) and the Cps35 subunit of COMPASS (34) are important for the general activity of Dot1 and the synthesis of higher methylation states of H3K79. Whatever the mechanism, our initial structure-function studies (Fig. 5D) suggest that the Sirt1 N-terminal domain is necessary and virtually sufficient to mediate the inhibitory effects.

It is also unclear to us at present whether Dot1 and Sirt1 are part of a stable macromolecular complex or whether their interaction is transient through chromatin. The interaction of Dot1 and Sirt1 may also be indirect, mediated by an intermediary protein that is perhaps regulated by these enzymatic activities.

Aldosterone Regulation of Sirt1 and α-ENaC Gene Expression

Our current finding that aldosterone down-regulates Sirt1 mRNA expression (Fig. 6B) in a coordinate manner with what we observed for Dot1 (6) and Af9 (7) suggests the possibility of common mechanisms controlling the expression of these genes. Potentially this could be related to the action of transcription factors at gene control regions that are common to the 3 genes. Sirt1 mRNA levels were down-regulated within 3 h, but remained relatively constant at this lower level over the remainder of the 24 h tested, whereas α-ENaC mRNA expression began to increase at 3 h, and continued to increase through later time points. In the ChIP assays, the down-regulation of Sirt1 association with chromatin at the R0 and R1 subregions of the α-ENaC promoter was apparent at 2.5 h and substantial at 5 h of aldosterone treatment. Whereas aldosterone decreases the expression of both Dot1 (6) and Sirt1 in mIMCD3 cells, this effect is not nearly so dramatic as the effect of the hormone on the chromatin-based association of the two proteins with subregions R0 and R1 of the α-ENaC promoter (Fig. 6C and Ref. 6). This suggests that aldosterone may also inhibit the binding affinity of the Dot1-Sirt1 complex to these subregions as it does for the Dot1-Af9 complex, in the latter case via Sgk1 (7). We have not yet tested for effects of Sgk1 on the Dot1-Sirt1 complex.

Our time course studies provide mechanistic insights into aldosterone-mediated induction of α-ENaC transcription. In the first 2 h of aldosterone exposure, Dot1 and Sirt1 exhibited lower levels of mRNA expression (Fig. 6B) and greatly reduced chromatin association with the R0 and R1 subregions of the α-ENaC promoter (Fig. 6C). Dot1 mRNA levels return to baseline by 7 h (6), whereas Sirt1 mRNA levels remain suppressed for the full 24 h studied (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, decrements in methylation of histone H3K79me2 in bulk histones are first observed at 6 h of aldosterone treatment, and this lower level is maintained, like that of Sirt1, throughout the first 24 h (6). Presumably, the effects of aldosterone-liganded MR interactions with the GREs in the 5′-flanking region of the α-ENaC gene (3) drive the continued increases in α-ENaC mRNA expression when the levels of Sirt1 mRNA and methylated histone H3K79 are static.

Our finding that the inhibitory effect of Sirt1 on aldosterone-induced α-ENaC promoter activity was much greater than, and additive to, that of the MR antagonist spironolactone (Fig. 7A), yet did not alter aldosterone inducibility of a GRE-driven test promoter (Fig. 7B), suggests MR independence of the Sirt1 effect. This result is consistent with recent findings in mice genetically engineered to lack MR expression specifically in the collecting duct principal cells (35). Treatment of these mice with amiloride, a specific blocker of ENaC, yielded an increase in the excreted part of the sodium filtered by the kidney comparable with that of wild type mice, indicating that ENaC activity was largely intact in the principal cells despite MR inactivation (35). The teleological reason for having MR-dependent and -independent effects on α-ENaC transcription is unclear at this time.

Dot1-Af9 and Dot1-Sirt1 Repressor Complexes

Because neither Dot1 nor Sirt1 has yet been shown to bind directly DNA, and we did not detect the DNA-binding protein Af9 in the Sirt1 immunoprecipitated complexes, it remains to be established how the Dot1-Sirt1 complex associates with specific regions of the α-ENaC promoter. Presumably, either Dot1 or Sirt1, or conformations specific to their complex, interact with a protein with DNA binding activity. It will be important to elucidate the distinctive actions of the Dot1-Af9 and Dot1-Sirt1 repressor complexes, whether Af9 and Sirt1 are mutually exclusive for interaction with Dot1, and whether the two complexes are subject to independent regulation.

Because no demethylase specific for H3K79 has yet been identified, the Sirt1 interaction may be a mechanism to modulate the level of Dot1 activity and its effects on chromatin. The present results also lead to the expectation that novel Sirt1 functions and targets will be discovered. Moreover, in the broader context of other genes, the functional and physical coupling of two proteins capable of modifying chromatin should further our understanding of gene regulation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK075565 (to B. C. K.).

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

- Dot1

- disruptor of telomeric silencing

- Af9

- ALL1-fused gene from chromosome 9

- Sir2

- silent information regulator 2

- Sgk1

- serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- GRE

- glucocorticoid-response element

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- RT

- reverse transcriptase

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- qPCR

- quantitative.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossier B. C., Pradervand S., Schild L., Hummler E. (2002) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 877–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schild L. (1996) Nephrologie 17, 395–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mick V. E., Itani O. A., Loftus R. W., Husted R. F., Schmidt T. J., Thomas C. P. (2001) Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husted R. F., Volk K. A., Sigmund R. D., Stokes J. B. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293, F813–F820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W., Hayashizaki Y., Kone B. C. (2004) Biochem. J. 377, 641–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W., Xia X., Jalal D. I., Kuncewicz T., Xu W., Lesage G. D., Kone B. C. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C936–C946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W., Xia X., Reisenauer M. R., Hemenway C. S., Kone B. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18059–18068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W., Xia X., Reisenauer M. R., Rieg T., Lang F., Kuhl D., Vallon V., Kone B. C. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 773–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer M. S., Kahana A., Wolf A. J., Meisinger L. L., Peterson S. E., Goggin C., Mahowald M., Gottschling D. E. (1998) Genetics 150, 613–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederiks F., Tzouros M., Oudgenoeg G., van Welsem T., Fornerod M., Krijgsveld J., van Leeuwen F. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 550–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacoste N., Utley R. T., Hunter J. M., Poirier G. G., Côte J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30421–30424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Leeuwen F., Gafken P. R., Gottschling D. E. (2002) Cell 109, 745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liou G. G., Tanny J. C., Kruger R. G., Walz T., Moazed D. (2005) Cell 121, 515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michishita E., Park J. Y., Burneskis J. M., Barrett J. C., Horikawa I. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4623–4635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avalos J. L., Bever K. M., Wolberger C. (2005) Mol. Cell 17, 855–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanno M., Sakamoto J., Miura T., Shimamoto K., Horio Y. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6823–6832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnin M. S., Donigian J. R., Pavletich N. P. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 621–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zschoernig B., Mahlknecht U. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 381, 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandithage R., Lilischkis R., Harting K., Wolf A., Jedamzik B., Lüscher-Firzlaff J., Vervoorts J., Lasonder E., Kremmer E., Knöll B., Lüscher B. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 180, 915–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michan S., Sinclair D. (2007) Biochem. J. 404, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaquero A., Scher M. B., Lee D. H., Sutton A., Cheng H. L., Alt F. W., Serrano L., Sternglanz R., Reinberg D. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 1256–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feige J. N., Auwerx J. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 303–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang B., Britton J., Kirchmaier A. L. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 381, 826–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo J., Nikolaev A. Y., Imai S., Chen D., Su F., Shiloh A., Guarente L., Gu W. (2001) Cell 107, 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaziri H., Dessain S. K., Ng Eaton E., Imai S. I., Frye R. A., Pandita T. K., Guarente L., Weinberg R. A. (2001) Cell 107, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunet A., Sweeney L. B., Sturgill J. F., Chua K. F., Greer P. L., Lin Y., Tran H., Ross S. E., Mostoslavsky R., Cohen H. Y., Hu L. S., Cheng H. L., Jedrychowski M. P., Gygi S. P., Sinclair D. A., Alt F. W., Greenberg M. E. (2004) Science 303, 2011–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung F., Hoberg J. E., Ramsey C. S., Keller M. D., Jones D. R., Frye R. A., Mayo M. W. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 2369–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong S., Weber J. D. (2007) Biochem. J. 407, 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouras T., Fu M., Sauve A. A., Wang F., Quong A. A., Perkins N. D., Hay R. T., Gu W., Pestell R. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10264–10276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amat R., Solanes G., Giralt M., Villarroya F. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34066–34076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim E. J., Kho J. H., Kang M. R., Um S. J. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 277–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng H. H., Dole S., Struhl K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33625–33628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altaf M., Utley R. T., Lacoste N., Tan S., Briggs S. D., Côté J. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 1002–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J. S., Shukla A., Schneider J., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Florens L., Bhaumik S. R., Shilatifard A. (2007) Cell 131, 1084–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronzaud C., Loffing J., Bleich M., Gretz N., Gröne H. J., Schütz G., Berger S. (2007) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 1679–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]