Abstract

The Agglutinin-Like Sequence (ALS) family of Candida albicans includes eight genes that encode large cell-surface glycoproteins. The high degree of sequence relatedness between the ALS genes and the tremendous allelic variability often present in the same C. albicans strain complicated definition and characterization of the gene family. The main hypothesis driving ALS family research is that the genes encode adhesins, primarily involved in host-pathogen interactions. Although adhesive function has been demonstrated for several Als proteins, the challenge of studying putative adhesins in a highly adhesive organism like C. albicans has led to varying ideas about how best to pursue such investigations, and results that are sometimes contradictory. Recent analysis of alsΔ/alsΔ strains suggested roles for Als proteins outside of adhesion to host surfaces, and a broader scope of Als protein function than commonly believed. The availability and use of experimental methodologies to study C. albicans at the genomic level, and the ALS family en masse, have advanced knowledge of these genes and emphasized their importance in C. albicans biology and pathogenesis.

Introduction

Candida albicans ALS1 was first described over ten years ago [1]. Since that time, research efforts have focused on understanding the relatedness of ALS1 to the larger family of ALS genes and exploring the function of the Als proteins. Functional studies have focused primarily on the hypothesis that Als proteins are C. albicans adhesins. Many advances have occurred in Candida research during the same time period including completion of the C. albicans genome sequence and development of resources for expression profiling at the genomic level. Since the last review of the ALS family literature [2], many reagents and approaches specific for study of the ALS family in C. albicans have been described. These developments led to large advances in the understanding of the ALS family and its place in the C. albicans genome and proteome. The purpose of this review is to summarize current information about the ALS genes and their encoded proteins and to define new challenges for the future of ALS family research.

ALS gene organization and ALS family composition

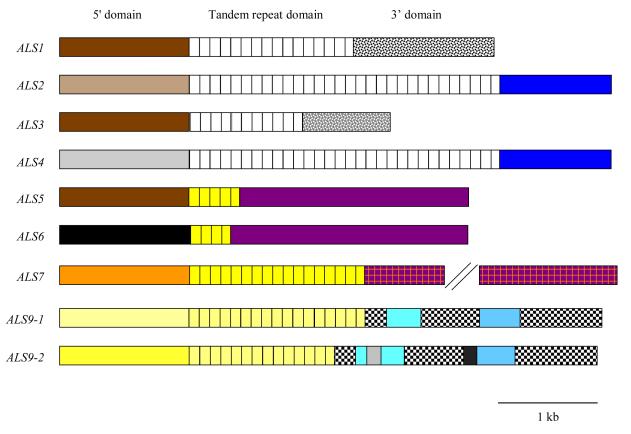

Since the basic organization of ALS genes was described previously [2], only a brief discussion is included here. Described in the simplest terms, ALS genes have three general domains (Fig. 1A) [2]. The 5′ domain includes approximately 1300 bp and encodes a protein region that has a relative lack of glycosylation in the initial 320 to 330 amino acids. Some Als proteins are predicted to be N-glycosylated within this region [2]. This region is followed by approximately 100 amino acids that are rich in serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr), a composition predicted to be heavily glycosylated. However, production of Als5p fragments in S. cerevisiae, demonstrated a lack of glycoslyation of this region of the protein [3]. It is unknown whether C. albicans-produced proteins are similarly unmodified or if observations about Als5p can be extrapolated across the entire Als family. Following the ALS gene 5′ domain is a central domain consisting entirely of tandemly repeated copies of a 108-bp sequence. The tandemly repeated sequence is somewhat variable, but each encodes a Ser/Thr-rich amino acid sequence and many copies contain a consensus N-glycosylation sequence. At high stringency on a Southern blot, the tandem repeat sequences cross-hybridize between ALS1, ALS2, ALS3, and ALS4. The tandem repeat sequences of ALS5, ALS6 and ALS7 also cross-hybridize, while the tandem repeat sequences of ALS9 are unique by these criteria. Subfamilies of ALS genes were proposed based on cross-hybridization between the tandem repeat sequences [2]. All ALS tandem repeat domains appear to encode a heavily N- and O-glycosylated protein that should have an extended conformation. The last Als domain is the C-terminal domain, which is the least conserved in length and sequence, but in all cases, encodes a Ser/Thr-rich protein with many consensus N-glycosylation sites. Similar to the tandem repeat domain, this region of the protein is expected to assume an extended conformation. The presence of a secretory signal sequence at the N-terminus and a GPI anchor addition sequence at the C terminus of each predicted protein sequence is consistent with localization of the Als proteins to the C. albicans cell wall [4-7].

Fig. 1.

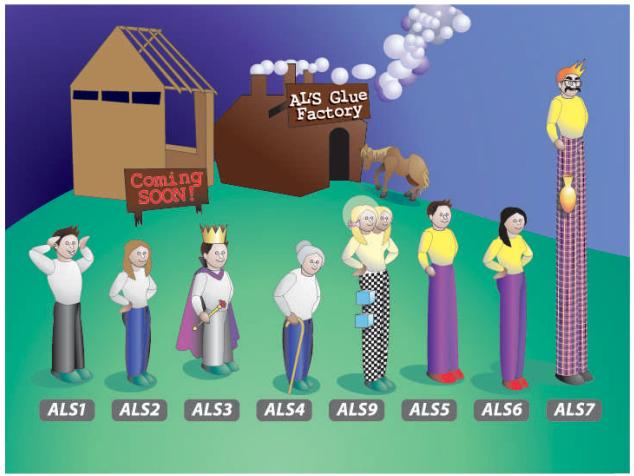

(A). Line drawing showing selected features of the C. albicans ALS genes. Color coding is used to show regions of similarity between genes and matches the color coding used in Fig. 1B. The length of the 5′ domain is similar in all ALS genes (approximately 1.3 kb) [1]. An “N” denotes the location of sequences encoding consensus N-glycosylation sites. The tandem repeat domain is drawn as individual repeated units to emphasize the composition of this portion of the coding region. The number of tandemly repeated copies in each ALS gene varies by C. albicans strain, and often between alleles within the same strain. For all genes except ALS9, the tandem repeat copy number depicted here represents the most common allele or mean of tandem repeat copy number observed from analysis of C. albicans strain collections (see text). For ALS9, the two alleles from strain SC5314 are shown [9, 10]. The variable length of the 3′ domain for each ALS gene is drawn to scale. There is a repeated domain in the 3′ end of ALS7 that is of variable length. The location of the repeated region is marked with parallel, diagonal lines. (B). An anthropomorphic presentation of ALS gene relationships: the updated C. albicans ALS family portrait. A similar image was published earlier [2] with detailed explanations of the meaning of various elements in the drawing. Briefly, heads of the human figures represent the 5′ domain of an ALS gene, torsos represent the central tandem repeat domain, and legs depict the 3′ domain. Portions of each human figure (hair, T-shirts, trouser legs and shoes) are color coded to indicate regions of high sequence identity/similarity between the various ALS genes. Differences between this image and the one published previously result from data that are summarized in the text of this manuscript. ALS8 was removed from the figure since that coding region is identical to ALS3 and encoded by a single locus [8]. ALS3 is wearing royal robes to indicate that deletion of this gene makes results in the largest decrease in C. albicans adhesion in the assays published to date [8]. This new diagram also depicts the allelic diversity found in ALS9 in strain SC5314 [9] including 5′ domain sequences that differ by 11% (represented by the two nearly identical heads) and the Variable Block regions of sequence present in the ALS9 3′ domain (shown as blocks on the trouser legs). The halo around one of the ALS9 heads indicates that a contribution to endothelial cell adhesion was measurable for the ALS9-2 5′ domain, but not for the corresponding region of ALS9-1 [10]. The new building under construction in the background of the image represents non-adhesive functions that have been detected for the Als proteins [12]. (Artwork by Kerry Helms, The Design Group @ Vet Med, University of Illinois, Urbana).

An updated version of the C. albicans ALS family portrait is shown in Fig. 1B. A detailed description of the meaning of the various elements of the drawing was included in the previous ALS review [2], so an abbreviated version is presented here. One major change between this figure and the previous one is the deletion of ALS8, which is the same locus as ALS3 [8]. Another major change arose from the more detailed characterization of ALS9. A large degree of sequence variation (11%) was found within the 5′ domain of ALS9 alleles in strain SC5314 [9]. Also, within the 3′ domain of each ALS9 allele, extra nucleotides were present in two regions of ALS9-2 designated as Variable Block 1 (VB1) and Variable Block 2 (VB2). Analysis of C. albicans isolates from the major genetic clades showed that both ALS9 alleles are widespread among these strains, the sequences of ALS9-1 and ALS9-2 are conserved among diverse strains, and recombinant ALS9 alleles have been generated during C. albicans evolution [9]. These data highlight one example of allelic diversity, which can be extreme between ALS alleles in the overall C. albicans population and also sometimes between ALS alleles within the same strain.

Misassembled ALS genes in the C. albicans genome project

Although the C. albicans genome project provided many clues about DNA fragments that represent ALS genes, only three of the ALS family ORFs were assembled correctly in Assembly 19 [11]. Characterization of the gene family mainly relied on efforts outside of the genome project, and these efforts dominated the initial literature on ALS research [1, 4, 9, 13-18]. Assembly failures in the ALS genes mainly occurred in the tandem repeat domains or from joining 5′ domains with the wrong tandem repeat and/or 3′ domains [11]. Particularly problematic was assembly of ALS2 and ALS4, which share a long and highly similar tandem repeat domain followed by nearly identical 3′ domains and 3′ flanking regions [4, 19]. Braun et al. [11] provide an annotated list of Assembly 19 orf numbers that correspond to ALS sequences.

Several ALS gene names (ALS10, ALS11, ALS12) were assigned to misassembled genome sequences. Because these versions of the genome assembly were used to design microarrays, these ALS gene names are found in the literature even though they do not represent real genes. For example, ALS10 consists of the 5′ domain of ALS2 fused to 3′ domain of ALS3, presumably due to sequence similarities within the tandem repeat domain. Since ALS2 and ALS3 occupy different chromosomes, ALS10 clearly does not exist in the C. albicans genome [4, 14]. The last two “virtual” ALS genes, ALS11 and ALS12 are fragments from the ALS9 and ALS4 coding regions, respectively. Sequence similarities within the ALS family (see color coding in Fig. 1) complicate microarray data interpretations. As the genome assembly matures [20] and oligonucleotide-based arrays are more commonly used, conclusions about ALS gene expression derived from microarrays will become more intelligible. PCR primer sets that can be used for semi-quantitative [21] or real-time [22] analysis of ALS gene expression were designed to distinguish between even the most highly related ALS sequences and provide validation of array-derived results.

ALS Genes in other Candida species

Among fungal genome sequences, there are numerous genes that share some physical similarity with the C. albicans ALS genes because they have a repeated sequence or encode a protein with a Ser/Thr-rich C-terminal domain and a consensus sequence for GPI anchor addition [23-26]. However, within the genome sequence of C. albicans strain SC5314, only eight open reading frames fulfill the criteria to be called ALS genes [11]. ALS genes, conforming to the definition provided above, are likely to exist in other Candida species. Cross-hybridization on Southern blots, and amplification of genomic DNA using degenerate PCR primers designed from C. albicans ALS sequences, suggested the presence of ALS-like genes in C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis and potentially in C. parapsilosis [27]. Putative ALS 5′ domain sequences were isolated, and cross-hybridization between the tandem repeat domains was observed between species. The nature of the 3′ domain of ALS genes in other Candida species remains to be revealed, but it is likely to be poorly conserved with the sequences found in C. albicans [27, 28]. Completion of the genome sequences of the other Candida species will reveal the answers to these questions. Links to the various Candida species genome sequencing project websites can be found at http://www.candidagenome.org. Completion of genome sequences for more distantly related Candida species will indicate whether they encode ALS-like sequences that could not be detected by cross-hybridization or by PCR with the degenerate primers. In each species, additional work will likely be required to correctly assemble the ALS sequences, especially if extensive repeated regions are present or if other areas of sequence similarity exist within the coding regions. Although there are numerous cell wall proteins with features similar to the Als proteins in S. cerevisiae [24, 29], no proteins that fit the Als family criteria have been found in that organism despite the numerous comparisons that have been made between the C. albicans ALS sequences and the sequence of S. cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin, the cell-surface adhesive glycoprotein that facilitates cell-cell contact between haploid S. cerevisiae cells during mating [2, 30, 31]. In silico analysis of the C. glabrata proteome showed many cell wall proteins with some features similar to Als proteins such as repeated sequences and Ser/Thr-rich regions [26]. However, none of the predicted proteins fit the definition for Als proteins that is provided here.

ALS allelic variation

Allelic variation is an important feature of the ALS family and one that can be lost in genome sequencing data, especially if emphasis is placed on deriving a haploid assembly. Much of the allelic variation for ALS genes occurs within the tandem repeat domain and is manifested as differing numbers of 108-bp tandemly repeated copies between ALS alleles. Frequently, these alleles are in the same C. albicans strain, so among the sequences from SC5314, most loss of allelic variation will be from inclusion of one allele length, rather than two, in the genome database. Examples of allelic diversity in strain SC5314 were shown for the three ALS genes that are contiguous on chromosome 6: ALS5, ALS1 and ALS9 [9]. Construction of double mutant strains combined with various PCR strategies showed that the larger allele of each gene is located on the same chromosome copy and the smaller alleles for each gene are on the other copy. The identity of the alleles and their chromosomal arrangement may vary in each C. albicans strain.

The fact that the tandemly repeated sequence copy number varied by allele was observed initially for ALS1 using a small number of C. albicans strains [1]. This work was expanded to examine larger numbers of C. albicans isolates and additional ALS genes. For example, Lott et al. [32] studied over 100 bloodstream isolates and found that the most common ALS1 allele had 16 copies of the tandem repeat sequence with a copy number range from 4 to 37. Examination of ALS7 allelic variation in a larger group of strains showed that the majority of isolates within a group called the general-purpose-genotype (GPG) cluster had between 14 and 17 tandem repeat copies in the central domain, and that these alleles were much less common in strains outside of the cluster [33]. In contrast to the data for ALS1 and ALS7, there was less variation in the number of tandem repeat copies in ALS5 and ALS6 with a mean of nearly 5 copies for ALS5 and nearly 4 copies for ALS6 [34]. Variation in the number of tandem repeat copies was associated with Als protein function for alleles of ALS3 [35]. Als3p proteins in strain SC5314 have either 9 or 12 copies of the tandem repeat sequence. Proteins with 12 repeat copies contribute more to C. albicans adhesion to endothelial or epithelial cells in a 6-well tissue culture plate adhesion assay than do those with 9 copies. C. albicans strains also tended to pair a shorter ALS3 allele with a longer ALS3 allele, suggesting that perhaps each allele has a unique function. Similar to data for ALS5 and ALS6, clade-specific tendencies in tandem repeat copy number were observed for ALS3 [34, 35]. Other genes in the family remain to be studied in such a detailed manner, but from a preliminary look at the various isolates, it is apparent that the tandem repeat domains of ALS2 and ALS4 are quite large, with a mean copy number over 30; the mean for ALS9 is closer to that observed for ALS1 (J.A. Nuessen and L. L. Hoyer, unpublished observations).

ALS allelic variability occurs in regions of the gene other than the tandem repeat domain. The example of variation in the 5′ domain coding regions of ALS9 was described above. Variation in the 5′ domain of ALS5 was also documented although it is not as extensive as that observed in ALS9 [18, 34]. DNA sequencing of the 5′ domain from various C. albicans clinical isolates showed a range of ALS5 sequence variation with some alleles resembling ALS1, which suggested recombination between the contiguous ALS5 and ALS1 loci [34]. The presence of repeated regions in other portions of the ALS genes also contributes to allelic diversity such as the VASES region of ALS7 [17, 33]. The VASES region was named because it contains varying numbers of copies of a repeated sequence that encodes the amino acid sequence Val-Ala-Ser-Glu(E)-Ser [17]. The repeated region is a complex assembly of four different repeated sequence units that contributes extreme allelic diversity to the ALS7 3′ domain [33]. ALS9 also provides an example of allelic sequence diversity within the 3′ domain where the variable sequence blocks (VB1 and VB2) are located [9, 10]. These extra sequences may or may not be included in a given ALS9 allele. PCR genotyping of various C. albicans isolates demonstrated the existence of the various allelic combinations of these sequences, suggesting extensive recombination between the ALS9 variants. Understanding allelic diversity for the ALS genes is important so that the results from functional analysis of a protein encoded by a single allele can be placed into an appropriate context of allelic variation within the larger population of C. albicans strains.

ALS gene expression

Initial studies of ALS gene expression used Northern blots. This method worked well for some ALS genes [1, 4, 6, 14, 36, 37, 38], was difficult for others [33], and unsuccessful for several genes in the family [4]. Lack of detectable transcript for some ALS genes suggested that they may require in vivo conditions for expression or that transcript level was quite low in cultured cells. To further investigate ALS gene expression and extend this analysis to C. albicans cells from clinical specimens and disease models, an RT-PCR assay was developed for the ALS family [21]. This assay was used to examine ALS gene expression in C. albicans cells from oral specimens from HIV-positive patients [39], vaginal specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic women [40], a hyposalivatory rat model of oral candidiasis [39], murine models of vaginal [40] and disseminated candidiasis [41], model denture and catheter biofilms [21], and the buccal, esophageal and vaginal reconstituted human epithelium models [21, 40]. In general, expression of all ALS genes could be detected in the various specimens studied, with expression of certain genes more likely to fall below the detection limit of the assay depending on the specimen. In most specimens, transcription of ALS6 and ALS7 was difficult to detect suggesting these genes are transcribed at a lower level than others in the ALS family [21, 39, 41]. When clinical vaginal specimens and those from models of vaginal candidiasis were examined, detection of ALS4 was more difficult than observed in clinical oral specimens and models of oral disease [40]. These results suggested a host-site-specific effect on regulation of ALS genes. Gene expression results for C. albicans taken from disease model systems accurately mirrored those observed from analysis of human clinical specimens, validating the model systems for phenotypic analysis of alsΔ/alsΔ mutant strains [39, 40].

Another general conclusion from this series of studies was that some ALS genes appear to be regulated by large increases and decreases in transcriptional level while others are consistently transcribed at lower levels regardless of the source of the C. albicans cells. Examples of the former group are ALS1, ALS2 and ALS3. In contrast, ALS6 and ALS7 are consistently more difficult to detect suggesting that the maximal transcription level for these genes may always be quite low relative to others in the family. These conclusions held true using GFP reporter constructs in a murine model of disseminated disease [41] and were substantiated using a quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay for the ALS family [22]. This low level of transcriptional activity for some of the ALS genes may not indicate repression, but instead, suggest that only a low level is required to produce enough protein to complete the required function. Indeed, if transcriptional levels reflect protein synthesis levels, certain Als proteins will be abundant on the C. albicans cell surface while others will be present in scant quantities. It is still possible that environmental conditions will be identified where the seemingly quiet genes are transcribed at a high level. However, since transcriptional activity of these genes was relatively low in clinical specimens, it is less likely that the conditions identified will have widespread meaning for pathogenesis.

One area of study that has received some attention, but requires much more investigation, involves understanding ALS gene expression in the context of regulatory pathways that are important for C. albicans morphology and/or pathogenesis. The first report that studied ALS gene expression in the context of such regulatory pathways was by Braun & Johnson [37] who assessed the contributions of TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 to C. albicans filamentation. One of the genes included in the analysis was ALS1, although expression of this gene is not limited to germ tube or hyphal forms [22] and the Northern blot probe used in the study was not specific for ALS1. Knowledge of ALS allelic sizes in strain SC5314 and expression patterns of the ALS genes [1, 14, 22] shows that the multiple bands observed in the Northern blots represent ALS1 and ALS3. From the published Northern blot, Braun & Johnson [37] concluded that CPH1 does not affect expression of either ALS1 or ALS3, that EFG1 is required for expression of both ALS1 and ALS3, and that TUP1 is a repressor of ALS1. Another conclusion that can be reached from the Northern blot is that ALS1 expression increases dramatically when C. albicans cells are inoculated into fresh growth medium. This result was demonstrated using a PALS1-GFP reporter strain that was grown in conditions that promote formation of either yeast or germ tubes [22].

Conclusions about ALS1 regulation, similar to those of Braun & Johnson [37], were derived using Northern blot analysis [6]. In this work, ALS1 transcript was not detectable in efg1/efg1 cells, but was observed in cph1/cph1, tup1/tup1 and cla4/cla4 strains. Reintegration of a wild-type copy of EFG1 restored ALS1 transcript to the Northern blot and constitutive expression of ALS1 altered cellular morphology to a filamentous form, suggesting that ALS1 is a downstream effector of EFG1.

Leng et al. [42] focused on ALS3 regulation in a study that demonstrated that Efg1p is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Using Northern blot analysis, ALS3 transcript was not detected in an efg1/efg1 strain while mutation of CPH1 did not affect ALS3 transcript level. Efg1p was shown to interact with the E box sequence at nucleotides -196 to -106 within the ALS3 promoter. Formation of an Efg1p-dependent complex with the ALS3 promoter was demonstrated with extracts from both yeast and hyphal cells. Recent work by the same group defined two activation regions within the ALS3 promoter [43]. One site is essential for ALS3 activation during hypha formation and the other site increases the amplitude of the activation. This work also demonstrated regulation of ALS3 by a number of transcription factors including Efg1p, Cph1p, Tec1p, Bcr1p, Nrg1p, Rfg1p and Tup1p.

Als protein adhesive function

Sequence features of ALS genes suggested that the encoded proteins are localized at the C. albicans cell surface. One analysis showed that Als1p and Als3p were released from the C. albicans cell wall with β-1,6-glucanase treatment [36]. In another analysis, Als1p and Als4p were released using HF-pyridine and/or Quantazyme treatment [44]. Linkage of each Als protein into the C. albicans cell wall has not been established experimentally, but instead, is assumed from the predicted amino acid sequences or from extrapolation of published localization data. It is formally possible for some Als proteins to be localized in the cell membrane with the N-terminal domain sequences exposed on the C. albicans cell surface. Testing this hypothesis would be facilitated by the availability of reagents that are specific for individual Als proteins.

Perhaps the most important point to pursue regarding the Als family is to determine the function of the individual Als proteins and to assess their contribution to C. albicans pathogenesis. Comparisons between Als1p and S. cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin led to the hypothesis that Als1p functions in adhesion. Lack of evidence of C. albicans haploid forms suggested that Als1p might adhere to host surfaces, rather than to other C. albicans cells [1]. Two studies were published in which an ALS gene was isolated from a C. albicans genomic library because it conferred adhesive properties on the relatively non-adhesive S. cerevisiae. In the first, heterologous expression of ALS5 (initially called ALA1) resulted in S. cerevisiae cells that could bind to fibronectin, type IV collagen, laminin and buccal epithelial cells [13]. In the next, heterologous expression of ALS1 resulted in S. cerevisiae cells that bound to vascular endothelial and FaDu pharyngeal epithelial cells [45]. These studies further supported the idea that Als proteins are adhesins.

Two lines of approach have been used to test the hypothesis that Als proteins are adhesins. One involves construction of C. albicans mutant strains and the other involves heterologous overexpression of ALS genes in S. cerevisiae. Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages. The S. cerevisiae system is easier to use because of the more complicated nature of constructing mutant C. albicans strains and because S. cerevisiae is an inherently less adhesive organism than C. albicans. Despite its relative ease of use, conclusions drawn from heterologous expression of C. albicans genes in S. cerevisiae may not accurately reflect protein function in C. albicans because of differences in codon usage [46] and glycosylation [47]. Heterologous expression also typically relies upon strong promoters that may overproduce Als proteins compared to the levels produced in C. albicans, resulting in a uniform, dense coating of Als protein on the fungal cell surface. This abundance and distribution of protein may not reflect what is found in C. albicans. Functional analysis using overexpression of ALS genes in S. cerevisiae also assumes that Als proteins act alone and rules out the possibility to detect function that depends on association with another Als protein. The S. cerevisiae system also cannot reveal truly divergent function within the ALS family, especially if those functions are specific to C. albicans. Finally, reports of functional analysis in S. cerevisiae typically investigate one ALS allele, and often do not indicate the identity of that allele. Ignoring allelic variation may lead to incorrect or oversimplified functional conclusions. Functional analysis in C. albicans offers the advantage of working in the native organism with native gene expression levels and protein localization. However, working in C. albicans requires an understanding of gene expression patterns in order to select assay conditions. C. albicans also may exhibit compensatory responses to gene deletion that mask the phenotypic effect of gene loss [19]. Finally, mutant construction in C. albicans has been associated with inflicting other damage on the strain, which may go undetected [48, 49]. Table 1 summarizes adhesive functional data from both experimental approaches.

Table 1.

Adhesion assay data summary for C. albicans alsΔ/alsΔ and S. cerevisiae ALS overexpression strains

| Gene | Experimental Approacha |

Endothelial Cells | Epithelial Cells | Fibronectin | Laminin | Gelatin | Type IV Collagen |

τφ+ Peptidesb |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUVEC Monolayer | Buccal | FaDu Monolayer | ||||||||

| ALS1 | C.a. mutant |  |

NC |

cDown cDown |

|

c c

|

nt | nt | nt | 6, 8, 50 |

| S.c. overexp. | nt | + | nt | + | 45, 51-53 | |||||

| ALS2 | C.a. mutantd | Down | NC | nt | NC | NC | nt | nt | nt | 19 |

| S.c. overexp. | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | ||

| ALS3 | C.a. mutant |  |

Down |  |

|

c c

|

nt | nt | nt | 8, 34 |

| S.c. overexp. | nt | + | nt | nt | 53 | |||||

| ALS4 | C.a. mutant | Down | NC | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | 19 |

| S.c. overexp. | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | ||

| ALS5 | C.a. mutant |  |

Up | nt |  |

nt | nt | nt | nt | 54 |

| S.c. overexp. | + | + | + | + | + | + | 13, 51-53 | |||

| ALS6 | C.a. mutant | Up | Up | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | 54 |

| S.c. overexp. | - | nt | - | - | - | + | nt | nt | 53 | |

| ALS7 | C.a. mutant | Up | Up | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | 54 |

| S.c. overexp. | - | nt | - | - | - | - | nt | nt | 53 | |

| ALS9 | C.a. mutant |  |

NC | nt | nt |  |

nt | nt | nt | 10 |

| S.c. overexp. | nt | - | - | - | nt | nt | 53 | |||

Adhesion was tested using C. albicans strains in which ALS genes were disrupted or deleted, or S. cerevisiae strains overexpressing an ALS gene. Adhesion to endothelial and FaDu epithelial cells was tested using monolayers of cultured cells. Buccal epithelial adhesion assays were conducted in suspension using freshly isolated cells. Proteins and peptides for adhesion assays were either coated onto tissue culture grade plastic or bound to magnetic beads. Details of adhesion assay methods can be found in the references cited at the end of each row of data. For analysis of C. albicans mutant strains, “Down” = statistically significant decreased adhesion compared to a wild-type control, “Up” = increased adhesion; “NC” = no change (lack of a significant difference). For analysis of S. cerevisiae overexpression strains, “+” = expression of the gene increases adhesion, “-” = expression of the gene does not increase adhesion. For all assays, “nt” = not tested. Where present, solid boxes indicate results that concur between the experimental methods while dashed boxes indicate conflicting results from the two methods.

The “τφ+” motif consists of amino acids with a high turn propensity (τ = A, D, G, K, N, P or S), followed by an amino acid with a bulky hydrophobic or aromatic group (φ = F, H, I, L, M, T, V, W or Y) and “+” representing either R or K [52].

S.-H. Oh, X. Zhao, and L. L. Hoyer, unpublished results.

A C. albicans strain in which the second ALS2 allele was controlled by the MAL2 promoter was assayed (als2Δ/PMAL2-ALS2).

Results from deletion of ALS1 in C. albicans and overexpression of the gene in S. cerevisiae are consistent with the conclusion that Als1p functions in adhesion to vascular endothelial cell monolayers (Table 1). However, deletion of ALS1 in C. albicans does not affect adhesion to buccal or FaDu pharyngeal epithelial cells or to the buccal reconstituted human epithelial model [8] while the S. cerevisiae ALS1 transformant binds to FaDu epithelial cells [45, 53]. One published report shows decreased adhesion of an als1/als1 C. albicans strain to FaDu cells although controls for this assay potentially are problematic [50]. In this work a strain lacking HWP1, which encodes a well-characterized hypha-specific epithelial cell adhesin (reviewed in [55]) was also assayed. Lack of altered adhesion of the hwp1/hwp1 strain to epithelial cells was attributed to the assay of yeast forms even though incubation of the cells in the assay’s tissue culture medium for 3 h undoubtedly should have promoted hypha formation. Therefore, it remains controversial whether Als1p binds to epithelial cells. Deletion of ALS1 in C. albicans did not reduce adhesion to fibronectin or laminin, although the S. cerevisiae overexpression strain adhered to both proteins, as well as gelatin [8, 53].

Difficulty in deleting the second ALS2 allele led to construction and phenotypic testing of a strain where the allele was placed under control of the MAL2 promoter [19]. Under non-inducing conditions, this strain showed decreased adhesion to endothelial cells; adhesion to buccal epithelial cells, fibronectin or laminin was not different from a wild-type control strain (Table 1). Deletion of ALS4 also decreased C. albicans adhesion to endothelial cells, but not to epithelial cells [19]. ALS2 and ALS4 were not tested by overexpression in S. cerevisiae. Microarray analysis assessed the transcriptional profile of the als2Δ/ALS2-PMAL2 and als4Δ/als4Δ strains that were grown under the same conditions utilized for adhesion assays [19]. Loss of wild-type ALS2 function resulted in up-regulation of orf19.4765, which encodes a protein similar to S. cerevisiae cell wall protein CCW12 (ScCCW12; [56]). Although the up-regulated ORF is similar to ScCCW12, preliminary experiments showed that a C. albicans strain lacking both orf19.4765 alleles has a different phenotype than the S. cerevisiae ccw12Δ cells [19]. Microarray analysis of C. albicans strains lacking both ALS4 alleles did not reveal any significantly up-regulated genes [19]. Because of their sequence similarities, ALS2 and ALS4 expression cannot be dissected on a PCR-product-based array. Therefore, real-time RT-PCR was used to show that ALS2 expression is up-regulated in the als4Δ/als4Δ strain by approximately 3-fold while ALS4 expression was up-regulated to a similar degree in the strain lacking wild-type ALS2 activity [19]. These results suggest cell wall responses to mutation of either ALS2 or ALS4 and the potential for compensatory function within the Als family.

Deletion of ALS3 had the largest effect on C. albicans adhesion (Table 1). The mutant strain showed decreased adhesion to endothelial cells, buccal epithelial cells and FaDu monolayers [8, 35]. No change in adhesion to fibronectin or laminin was noted compared to the control strain. Overexpression of ALS3 in S. cerevisiae also resulted in adhesion to endothelial and epithelial cells, but also to fibronectin, laminin and gelatin [53]. Recent work supported the conclusion that Als3p is a fungal invasin that mimics host cell cadherins and induces C. albicans endocytosis by binding to N-cadherin on endothelial cells and E-cadherin on oral epithelial cells [57].

A tremendous amount of Als5p functional characterization has been done by heterologous expression in S. cerevisiae. Production of Als5p on the S. cerevisiae surface results in adhesion and aggregation properties that are similar to those observed in C. albicans [51]. Following adhesion, fungal cellular aggregation occurs as a result of a global cell surface conformational shift [58]. Work with lower-strength promoters, however, showed that Als5p-mediated cellular aggregation was not observed when ALS5 was expressed at reduced levels [51]. S. cerevisiae transformants overexpressing ALS5 adhere to endothelial cells, buccal and FaDu epithelial cells, fibronectin, laminin, gelatin, and type IV collagen [13, 53] (Table 1). Als5p adhesion is mediated by recognition of accessible serine, threonine or alanine patches and protein recognition is aided by exposure of a denatured protein backbone on the host cell [59, 60]. S. cerevisiae strains overexpressing ALS5 recognize many peptides with the consensus “τφ+” motif which consists of amino acids with a high turn propensity (τ = A, D, G, K, N, P or S), followed by an amino acid with a bulky hydrophobic or aromatic group (φ = F, H, I, L, M, T, V, W or Y) and “+” representing either R or K [52]. Studies of ALS5 expression in C. albicans indicate that, under the culture and disease model conditions studied, ALS5 expression is relatively low [21, 22, 39-41], suggesting that the global cell surface change observed in S. cerevisiae may not occur in C. albicans. Focal localizations of Als5p on the C. albicans cell surface, where a small surface area has a large number of Als5p proteins present, might be one way that the phenomena observed in the S. cerevisiae ALS5 transformants could occur similarly in C. albicans. ALS5-negative C. albicans isolates are identified frequently from patients with clinical disease [18, 34]. Deletion of ALS5 in these strains is mediated by direct repeats that flank the ALS5 coding region [34].

The functions of Als6p and Als7p are considerably less characterized compared to Als5p. Overexpression of ALS6 in S. cerevisiae resulted in adhesion to gelatin, while transformants overexpressing ALS7 did not adhere to any cells or proteins assayed (Table 1) [53]. Deletion of ALS5, ALS6 or ALS7 in C. albicans caused increased adhesion to both endothelial and epithelial cells (Table 1) [54]. This result is contrary to that expected for deletion of an adhesin, and could indicate that these Als proteins have an anti-adhesive effect similar to that observed when YWP1 is deleted in C. albicans [61]. Although the C. albicans als5Δ/als5Δ, als6Δ/als6Δ and als7Δ/als7Δ strains showed a 2- to 3-fold increase in adhesion compared to the wild-type control, additional experimentation is required to understand the basis of this phenotype since integration of a single wild-type allele was not sufficient to restore wild-type adhesion [54]. The need to reintegrate both wild-type alleles to restore wild-type function was noted for other C. albicans cell wall protein-encoding genes such as ECM33 [62].

Overexpression of ALS9 in S. cerevisiae resulted in adhesion of the transformants to laminin, but not to any of the other cells or proteins assayed (Table 1) [53]. Deletion of ALS9 in C. albicans reduced adhesion to endothelial cells, but not to epithelial cells [10]. Adhesion was attributed to the ALS9-2 allele, which is more prevalent in the general population of C. albicans clinical isolates than is the ALS9-1 allele. The C. albicans als9Δ/als9Δ strain did not show a decreased ability to bind laminin compared to the wild-type control strain [10].

Another role for Als proteins has been demonstrated in the context of C. albicans biofilm formation. Adhesive properties are important for biofilm formation, suggesting that Als proteins may function in this process. This suggestion was strengthened by the results of transcriptional profiling experiments that compared biofilm to planktonic cells [63]. In this work, gene expression from many biofilm growth conditions was summarized as a statistical measure of central tendency (mean or median) and compared to a similar summary value derived from gene expression measurements taken from a variety of planktonic culture conditions. ALS1 was the most differentially expressed gene in this study, suggesting its importance in biofilm formation. Given the sensitivity of ALS1 expression to growth stage of a culture [22], it is not surprising that the gene appears differentially expressed between a mature culture and one that is at an earlier growth stage. This study prompted others to investigate ALS gene expression in the context of biofilm formation [64, 65]. Nobile et al. [66] detected a modest role for Als1p in biofilm formation, but suggested that the protein is of lesser importance than Als3p. In an in vitro model of catheter biofilm development, a C. albicans als3/als3 strain was unable to form a mature biofilm, but instead, grew basal yeast layers without the subsequent hyphal layer [66]. Evaluation of the strain in an in vivo catheter biofilm model showed that the mutant was still capable of biofilm formation [66]. Systematic testing of C. albicans alsΔ/alsΔ strains also led to the conclusion that Als3p is required for wild-type biofilm formation on a silicone elastomer surface [66]. The nature of the adhesive role for Als3p in this context is open for debate. Since a C. albicans strain lacking Als3p can still adhere to the silicone elastomer substrate, and these cells have a yeast morphology in which ALS3 expression is unmeasurable [14], it is unlikely that Als3p functions in this early adhesion step. It is more likely that the protein is important at later developmental steps where hyphae are present. Systematic testing of the C. albicans alsΔ/alsΔ strains also showed that loss of wild-type ALS2 levels resulted in a biofilm with decreased mass [19].

Another way to explore the binding properties of Als proteins is to move away from displaying them on cell surfaces and toward production of recombinant proteins that include the binding domain. Localization of Als binding function to the N-terminal domain was proposed based on comparisons to data from the thorough characterization of S. cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin that showed binding function within the N-terminal half of the 650-amino acid protein [67-71]. Blocking adhesion of a C. albicans ALS1 overexpression strain with anti-Als1p raised against the N-terminal domain was consistent with localization of the Als1p binding function to that portion of the protein [6]. Deletion and mutation of Als1p N-terminal domain sequences with a concomitant decrease in endothelial cell adhesion of a S. cerevisiae transformant also suggested that binding function resides within the N-terminal domain [72]. Additionally, a polyclonal antiserum against Als1p blocked Als5p-mediated adhesion to fibronectin-coated magnetic beads [58]. Binding function of Als3p was localized to the N-terminal domain based on data that show blocking of adhesion with an anti-Als3p antibody preparation [7]. Buccal epithelial cell binding was restored to an als3Δ/als3Δ strain by production of a cell-surface fusion protein consisting of the N-terminal domain of Als3p displayed on the C-terminal half of alpha-agglutinin [7]. A fusion protein displaying the N-terminal domain of Als9-2p on the tandem repeat and C-terminal domains of Als9-1p supported the conclusion that endothelial cell binding activity was localized within the N-terminal sequences. At this time, it is generally accepted that Als protein adhesive activity is associated with the N-terminal domain although recent work by Rauceo et al. [3] suggested that the presence of the tandem repeat sequences in S. cerevisiae-produced Als5p enhances binding to fibronectin. Associating adhesive activity with the N-terminal domain opens avenues for further experimentation to determine which amino acid residues are critical for Als protein adhesion and for identification of the host cell ligands that participate in the binding interaction. An initial question to be answered is whether Als proteins recognize one or more host cell ligands. Studies in S. cerevisiae predict that Als1p and Als5p are able to bind to many host cell proteins and suggest that binding is degenerate [52]. Similarities in adhesion data for Als1p, Als3p and Als5p produced in S. cerevisiae suggest that the three proteins may share similar specificities [53]. Direct testing of this hypothesis in C. albicans would provide evidence to support or reject the validity of analyzing Als binding properties in the heterologous S. cerevisiae system. The hypothesis that Als proteins other than Als1p, Als3p, Als5p and Als9p localize function to the N-terminal domain still requires experimental confirmation, and this evidence is particularly important for the proteins for which adhesive function has yet to be demonstrated in C. albicans. It remains possible that these Als proteins have alternative roles and that other domains are important for those activities.

Als protein contribution to C. albicans pathogenesis

Reports of experiments to test the contribution of Als proteins to C. albicans pathogenesis in disease models are more limited than are the reports of testing adhesive function. The role of Als1p has been evaluated most thoroughly. Compared to a wild-type control, mice injected with a C. albicans als1/als1 strain had increased survival time in the tail vein model of disseminated disease [6, 50]. Pathogenesis in the mutant-inoculated animals appeared to lag behind that of the animals inoculated with the wild-type control strain; this trend was observed within the initial 28 h post-inoculation [6]. The als1/als1 strain also exhibited this decreased virulence in the early stages of disease in a model of oral candidiasis [73]. The mutant strain showed decreased adhesion to mouse tongues ex vivo [73]. An als1Δ/als1Δ mutant strain showed slightly reduced destruction of epithelial cells in the buccal reconstituted human epithelium tissue culture model, although there was no difference in adhesion of the mutant strain to the epithelial surface [8]. Loss of wild-type Als1p function slowed germ tube formation compared to the wild-type strain [6, 8]. This quality may be related to the delayed pathogenesis observed in the disease models.

The remainder of the collection of C. albicans strains lacking wild-type ALS gene function has been tested in both the buccal and vaginal reconstituted human epithelium model. Deletion of ALS3 showed the most marked effect in the RHE model with adhesion that was reduced to nearly zero and almost a total lack of RHE destruction [8]. Loss of wild-type ALS2 function decreased adhesion to and destruction of buccal RHE [19]. There was no difference from wild-type adhesion or epithelial destruction for strains deleted for ALS4, ALS5, ALS6, ALS7 or ALS9 [10, 19, 54]. Results for the vaginal RHE model mimicked those for the buccal RHE [54].

Als protein function in other cellular processes

Since the initial identification of Als1p and its comparison to S. cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin, the main hypothesis in this area of study is that the Als proteins are adhesins that function to promote C. albicans host-pathogen interaction. Experimental results are interpreted in these terms, sometimes without seriously considering the possibility that some of the Als proteins may have a different primary role in C. albicans biology and/or pathogenesis. Such an unexpected role was observed by noting that C. albicans als1Δ/als1Δ cells are smaller in size than cells of a wild-type control strain [12]. Evaluation of the effect of this size difference was studied using cells grown overnight to saturation in the complex medium YPD. This growth condition is the most common used to create a starter culture for evaluation of germ tube formation or pathogenesis of the C. albicans als1Δ/als1Δ strain. The size difference between als1Δ/als1Δ and wild-type cells was characterized using manual measurements of micrographs, Coulter counter analysis and flow cytometry. Flow cytometry was used to isolate populations of smaller wild-type cells to study their properties compared to larger cells of the same strain. Smaller cells were slower to form germ tubes when placed into germ tube-inducing growth conditions. This relationship between cell size and germ tube formation was already established in the C. albicans literature [74]. Smaller wild-type cells also showed a delay in pathogenesis compared to larger cells. The smaller overall cell size in the als1Δ/als1Δ population explains the apparent germ tube formation defect in the mutant cells and may also explain the delayed pathogenesis observed in disease models (see above). These observations suggest a role for Als1p in maintainance of wild-type C. albicans cell size, a process that may or may not involve adhesive function. Additional studies of Als protein function in C. albicans may reveal other unexpected roles for the proteins and indicate that the family is more than the set of adhesins that originally was hypothesized.

Can we derive an ALS family soundbyte?

From the initial observation of the existence of the ALS gene family, the questions of what the proteins do and why the family exists have been paramount. Observing that C. albicans encodes many gene families [75] raises more global questions regarding whether the organism uses gene families in a similar manner or whether answers to these questions will vary, depending on which gene family is considered. As knowledge is gathered about the biology and pathogenesis of C. albicans, summary comments that provide the answers to these global questions are sought, with the most pleasing answers delivered as easily remembered soundbytes. One current ALS family soundbyte is that the family encodes proteins that function in adhesion of C. albicans to extracellular matrix proteins [76]. The summary of ALS family data presented here demonstrates that the answer is not quite that simple. By evaluating current information about gene expression patterns and individual protein function, a larger picture of the ALS family can be derived. The process of deriving this summary soundbyte can be aided by revisiting the initial hypotheses for Als protein function.

Initially, Als proteins were hypothesized to be adhesins. Because of the diverse set of environmental niches that C. albicans occupies, it was envisioned that perhaps the adhesins varied in their binding specificity so that the most appropriate adhesin would be produced at each host site. Differential gene expression, driven by cues specific to the various host niches, was proposed to regulate production of the various adhesins. Functional redundancy was also a possibility to ensure that critical functions were preserved in the C. albicans genome. These hypotheses are developed mainly from considering the lifestyle of C. albicans in its human host. Current data suggest that it is easiest to demonstrate adhesive function of the Als proteins in endothelial cell monolayer assays (Table 1). These conclusions are not merely based on assay format since only some of the Als proteins show adhesive activity when assayed against epithelial cell monolayers. A hierarchy of adhesive activity seems to exist within the Als family, with greatest adhesive activity observed for the Als proteins that are derived from the genes with the highest maximal transcription level (ALS1, ALS2, ALS3) and diminishing contributions to adhesion for the genes that are transcribed at lower levels (ALS4 and ALS9). ALS5, ALS6 and ALS7, which are transcribed at the lowest levels appear to be anti-adhesins when assayed in C. albicans. This effect requires additional investigation and may involve up-regulation of other adhesin-encoding genes that respond to disruption of the ALS genes. Compensatory activity was observed in transcription of ALS2 and ALS4, suggesting that their proteins may have partially overlapping function. The common C-terminal domains of Als2p and Als4p raise the question of whether there is functional significance in this portion of the Als protein. The fact that many C. albicans strains taken from clinical infections have natural ALS5 deletions suggests that this gene may not be critical for pathogenesis processes or indicates redundancy of Als5p function within the family [34]. With the exception of ALS4 expression in the vaginal environment, gene expression evidence gathered to date suggests relatively consistent ALS transcriptional activity despite the location from which the C. albicans specimen is collected. This body of evidence argues against the hypothesis that ALS expression is tailored to provide the best adhesin at the appropriate host site. Instead, it suggests the presence of multiple functions, perhaps some of which are not mainly adhesion, at every host site assayed. The products of genes expressed at lower levels could play some role in fine-tuning the response of the proteins produced from the strongly expressed genes. Finally, the potential for Als proteins to participate in multiprotein complexes, to be localized in the cell membrane rather than in the cell wall, and to play unexpected roles, such as in signal transduction, cannot be ruled out. Collectively, the current evidence suggests that describing Als family function will require a very general soundbyte to recognize its multifunctional nature and role in diverse aspects of C. albicans biology and pathogenesis.

New and future directions for ALS family research

In addition to the ongoing efforts to characterize the structure and function of the individual Als proteins and to understand the role of the gene family in C. albicans biology and pathogenesis, ALS genes and proteins are being used in other research efforts. Several reports examine the use of Als protein fragments as an anti-Candida vaccine. Immunization of mice with the S. cerevisiae-produced N-terminal domain fragment of Als1p protected mice from a disseminated candidiasis challenge [77]. Subcutaneous injection was more effective than immunization by an intraperitoneal route [78]. Immunization was effective in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice [78], inbred and outbred mice [79]. Immunization protected against challenge by multiple C. albicans strains and also by challenge from other Candida species [79]. Immune response to the immunizaton is mainly cell-mediated [77]. A similar cell-mediated response as observed after immunization with the same region of Als3p [80]. Als3p was as protective as Als1p for disseminated candidiasis and more effective when tested in models of oral and vaginal disease [80].

The similarities between Als proteins and S. cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin were noted early in the work on the ALS family [1]. However, at that time, mating had not been described in C. albicans [81, 82]. If Als proteins are homologs of the S. cerevisiae mating agglutinin, they may play some role in this process in C. albicans. An initial report suggested that Als1p is not involved in C. albicans mating [83], however, the rest of the Als proteins remain to be tested.

Although dissection of the role of the Als proteins in C. albicans may have been too complex in the past, the recent years have brought advances in the strains, reagents and methodologies necessary to make these studies possible. A set of eight C. albicans strains, each with a single als/als mutation, is available [8, 10, 19, 54]. Three independently constructed als1/als1 strains have been reported in the literature [6, 8, 50]. Allelic variation has been defined for most of the ALS genes, which allows functional data to be placed into a global context [32-35]. Primer sets are available for real-time RT-PCR analysis of the ALS family [22] as are microarrays to analyze chromosomal changes [48] and altered transcriptional patterns that might occur due to the mutagenesis process. Knowledge of ALS gene expression patterns allows selection of assay conditions to evaluate the phenotypic effects of mutation. One set of reagents that would be quite valuable is a set of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), each specific for one of the Als proteins. These antibodies would provide information about cellular localization and abundance for the Als proteins. An anti-Als1p MAb was reported [6] and experiments with adsorption of polyclonal serum using the various als/als C. albicans strains demonstrate the feasibility for generating unique antibodies despite the overall similarity of the various Als proteins [7]. Most importantly, emphasis must be placed on studies of the Als family in C. albicans rather than in heterologous systems because the role of Als proteins in pathogenesis can only be evaluated in the native system. Conducting work at the whole-family level will answer the more global questions about why C. albicans encodes gene families and whether more than one paradigm exists for gene families in this organism.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Myra B. Kurtz. We thank the Hoyer laboratory team members, both past and present, for their dedication to studies of the ALS family and for their spirited camaraderie. We also thank our colleagues and collaborators for their experimental assistance, stimulating conversations and insightful comments that were often contributed at critical stages of our efforts. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant DE14158 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 RR16515-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hoyer LL, Shatzman AR Scherer S., Livi GP. Candida albicans ALS1: domains related to a Saccharomyces cerevisiae sexual agglutinin separated by a repeating motif. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:39–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyer LL. The ALS gene family of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:176–180. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)01984-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauceo JM, De Armond R, Otoo H, et al. Threonine-rich repeats increase fibronectin binding in the Candida albicans adhesin Als5p. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1664–1673. doi: 10.1128/EC.00120-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoyer LL, Payne TL, Hecht JE. Identification of Candida albicans ALS2 and ALS4 and localization of Als proteins to the fungal cell surface. J Bacteriol. 1998b;180:5334–5343. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5334-5343.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoyer LL, Clevenger J, Hecht JE, Ehrhart EJ, Poulet FM. Detection of Als proteins on the cell wall of Candida albicans in murine tissues. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4251–4255. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4251-4255.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Y, Ibrahim AS, Sheppard DC, et al. Candida albicans Als1p: an adhesin that is a downstream effector of the EFG1 filamentation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao X, Daniels K, Green CB, et al. Candida albicans Als3p is required for wild-type biofilm formation on silicone elastomer surfaces. Microbiology. 2006;152:2287–2299. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Cheng G, et al. ALS3 and ALS8 represent a single locus that encodes a Candida albicans adhesin; functional comparison between Als3p and Als1p. Microbiology. 2004;150:2415–2428. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26943-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao X, Pujol C, Soll DR, Hoyer LL. Allelic variation in the contiguous loci encoding Candida albicans ALS5, ALS1 and ALS9. Microbiology. 2003;149:2947–2960. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Hoyer LL. Unequal contribution of ALS9 alleles to adhesion between Candida albicans and vascular endotheial cells. Microbiology. 2007 doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/005017-0. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun BR, van het Hoog M, d’Enfert C, et al. A human-curated annotation of the Candida albicans genome. PLoS Genetics. 2005;1:36–57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Coleman DA, Kuhlenschmidt MS, Hoyer LL. ALS1 deletion reduces Candida albicans cell size: correlations between cell size, delayed filamentation and delayed virulence of the mutant strain. (Submitted)

- 13.Gaur NK, Klotz SA. Expression, cloning, and characterization of a Candida albicans gene, ALA1, that confers adherence properties upon Saccharomyces cerevisiae for extracellular matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5289–5294. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5289-5294.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoyer LL, Payne TL, Bell M, Myers AM, Scherer S. Candida albicans ALS3 and insights into the nature of the ALS gene family. Curr Genet. 1998;33:451–459. doi: 10.1007/s002940050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Wang Q, Chen JY. Cloning and identification of genes related with morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Sheng Wu Hua Xue Yu Sheng Wu Wu Li Xue Bao. 2000;32:509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Chen JY. Cloning and functional analysis of ALS family genes from Candida albicans. Sheng Wu Hua Xue Yu Sheng Wu Wu Li Xue Bao. 2000;32:586–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyer LL, Hecht JE. The ALS6 and ALS7 genes of Candida albicans. Yeast. 2000;16:847–855. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)16:9<847::AID-YEA562>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyer LL, Hecht JE. The ALS5 gene of Candida albicans and analysis of the Als5p N-terminal domain. Yeast. 2001;18:49–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200101)18:1<49::AID-YEA646>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Yeater KM, Hoyer LL. Analysis of the Candida albicans Als2p and Als4p adhesins suggests the potential for compensatory function within the Als family. Microbiology. 2005;151:1619–1630. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27763-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van het Hoog M, Rast TJ, Martchenko M, et al. Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R52. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green CB, Cheng G, Chandra J, et al. RT-PCR detection of Candida albicans ALS gene expression in the reconstituted human epithelium (RHE) model of oral candidiasis and in model biofilms. Microbiology. 2004;150:267–275. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green CB, Zhao X, Yeater KM, Hoyer LL. Construction and real-time RT-PCR validation of Candida albicans PALS-GFP reporter strains and their use in flow cytometry analysis of ALS gene expression in budding and filamenting cells. Microbiology. 2005;151:1051–1060. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundstrom P. Adhesion in Candida spp. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:461–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Groot PWJ, Hellingwerf KJ, Klis FM. Genome-wide identification of fungal GPI proteins. Yeast. 2003;20:781–796. doi: 10.1002/yea.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenhaber B, Schneider G, Wildpaner M, Eisenhaber F. A sensitive predictor for potential GPI lipid modification sites in fungal protein sequences and its application to genome-wide studies for Aspergillus nidulans, Candida albicans, Neurospora crassa, Saccharomyces cerevisaie and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weig M, Jansch L, Groβ U, et al. Systematic identification in silico of covalently bound cell wall proteins and analysis of protein-polysaccharide linkages of the human pathogen Candida glabrata. Microbiology. 2004;150:3129–3144. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyer LL, Fundyga R, Hecht JE, et al. Characterization of agglutinin-like sequence genes from non-albicans Candida and phylogenetic analysis of the ALS family. Genetics. 2001;157:1555–1567. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran G, Stokes C, Thewes S, et al. Comparative genomics using Candida albicans DNA microarrays reveals absence and divergence of virulence-associated genes in Candida dubliniensis. Microbiology. 2004;150:3363–3382. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caro LHP, Tettelin H, Vossen JH, et al. In silico identification of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored plasma-membrane and cell wall proteins of Saccharmyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1477–1489. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199712)13:15<1477::AID-YEA184>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipke PN, Wojciechowicz D, Kurjan J. AGα1 is the structural gene for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-agglutinin, a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions during mating. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3155–3165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser K, Tanner W. Purification of the inducible α-agglutinin of S. cerevisiae and molecular cloning of the gene. FEBS Lett. 1989;225:290–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lott TJ, Holloway BP, Logan DA, Fundyga R, Arnold J. Towards understanding the evolution of the human commensal yeast Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1137–1143. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Harrex AL, Holland BR, et al. Sixty alleles of the ALS7 open reading frame in Candida albicans: ALS7 is a hypermutable contingency locus. Genome Res. 2003;13:2005–2017. doi: 10.1101/gr.1024903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Jajko R, et al. Analysis of ALS5 and ALS6 allelic variability in a geographically diverse collection of Candida albicans isolates. (Under revision) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Oh S-H, Cheng G, Nuessen JA, et al. Functional specificity of Candida albicans Als3p proteins and clade specificity of ALS3 alleles discriminated by the number of copies of the tandem repeat sequence in the central domain. Microbiology. 2005;151:673–681. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27680-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapteyn JC, Hoyer LL, Hecht JE, et al. The cell wall architecture of Candida albicans wild-type cells and cell wall-defective mutants. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:601–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun BR, Johnson AD. TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2000;155:57–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandra J, Kuhn DM, Mukherjee PK, et al. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: development, architecture, and drug resistance. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5385–5394. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5385-5394.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green CB, Marretta SM, Cheng G, et al. RT-PCR analysis of Candida albicans ALS gene expression in a hyposalivatory rat model of oral candidiasis and in HIV-positive human patients. Med Mycol. 2006;44:103–111. doi: 10.1080/13693780500086527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng G, Wozniak K, Wallig MA, et al. Comparison between Candida albicans agglutinin-like sequence gene expression patterns in human clinical specimens and models of vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1656–1663. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1656-1663.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green CB, Zhao X, Hoyer LL. Use of green fluorescent protein and reverse transcription-PCR to monitor Candida albicans agglutinin-like sequence gene expression in a murine model of disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1852–1855. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1852-1855.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leng P, Lee PR, Wu H, Brown AJ. Efg1, a morphogenetic regulator in Candida albicans, is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4090–4093. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.4090-4093.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Argimon S, Wishart JA, Leng R, et al. Developmental regulation of an adhesin gene during cellular morphogenesis in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Euk Cell. 2007;6:682–692. doi: 10.1128/EC.00340-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Groot PW, de Boer AD, Cunningham J, et al. Proteomic analysis of Candida albicans cell walls reveals covalently bound carbohydrate-active enzymes and adhesins. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:955–965. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.955-965.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Y, Rieg G, Fonzi WA, et al. Expression of the Candida albicans gene ALS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae induces adherence to endothelial and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1783–1786. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1783-1786.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santos MA, Tuite MF. The CUG codon is decoded in vivo as serine and not leucine in Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1481–1486. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrero AB, Uccelletti D, Hirschberg CB, Dominguez A, Abeijon C. The Golgi GDPase of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans affects morphogenesis, glycosylation, and cell wall properties. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:420–31. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.420-431.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selmecki A, Bergmann S, Berman J. Comparative genome hybridization reveals widespread aneuploidy in Candida albicans laboratory strains. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1553–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wellington M, Rustchenko E. 5-fluoro-orotic acid induces chromosome alterations in Candida albicans. Yeast. 2005;22:57–70. doi: 10.1002/yea.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alberti-Segui C, Morales AJ, Xing H, et al. Identification of potential cell-surface proteins in Candida albicans and investigation of the role of a putative cell-surface glycosidase in adhesion and virulence. Yeast. 2004;21:285–302. doi: 10.1002/yea.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaur NK, Klotz SA, Henderson RL. Overexpression of the Candida albicans ALA1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in aggregation following attachment of yeast cells to extracellular matrix proteins, adherence properties similar to those of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6040–6047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6040-6047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klotz SA, Gaur NK, Lake DF, et al. Degenerate peptide recognition by Candida albicans adhesins Als5p and Als1p. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2029–2034. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2029-2034.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheppard DC, Yeaman MR, Welch WH, et al. Functional and structural diversity in the Als protein family of Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30480–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao X, Oh S-H, Hoyer LL. Deletion of ALS5, ALS6, or ALS7 increases adhesion of Candida albicans to human vascular endothelial and buccal epithelial cells. Med Mycol. 2007 doi: 10.1080/13693780701377162. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sundstrom P. Adhesins in Candida albicans. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:353–357. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mrsa V, Ecker M, Strahl-Bolsinger S, et al. Deletion of new covalently linked cell wall glycoproteins alters the electrophoretic mobility of phosphorylated wall components of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3076–3086. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3076-3086.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phan QT, Myers CL, Fu Y, et al. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rauceo JM, Gaur NK, Lee KG, et al. Global cell surface conformational shift mediated by a Candida albicans adhesin. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4948–4955. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.4948-4955.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaur NK, Smith RL, Klotz SA. Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing ALA1/ALS5 adhere to accessible threonine, serine, or alanine patches. Cell Commun Adhes. 2002;9:45–57. doi: 10.1080/15419060212187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaur NK, Klotz SA. Accessibility of the peptide backbone of protein ligands is a key specificity determinant in Candida albicans SRS adherence. Microbiology. 2004;150:277–284. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granger BL, Flenniken ML, Davis DA, Mitchell AP, Cutler JE. Yeast wall protein 1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2005;151:1631–1644. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez-Lopez RL, Monteoliva R, Diez-Orejas C, Nombela C, Gil C. The GPI-anchored protein CaEcm33p is required for cell wall integrity, morphogenesis and virulence in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2004;150:3341–3354. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Sanchez S, Iraqui I Aubert S., et al. Candida albicans biofilms: a developmental state associated with specific and stable gene expression patterns. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:536–545. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.536-545.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Conner L, Lahiff S, Casey F, et al. Quantification of ALS1 gene expression in Candida albicans biofilms by RT-PCR using hybridization probes on the LightCycler. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nailis H, Coenye T, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Deforce D, Nelis HJ. Development and evaluation of different normalization strategies for gene expression studies in Candida albicans biofilms by real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nobile CJ, Andes DR, Nett JF, et al. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesions in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wojciechowicz D, Lu CF, Kurjan J, Lipke PN. Cell surface anchorage and ligand-binding domains of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion protein α-agglutinin, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2554–2563. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cappellaro C, Baldermann C, Rachel R, Tanner W. Mating type-specific cell-cell recognition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cell wall attachment and active sites of a- and α-agglutinin. EMBO J. 1994;13:4737–4744. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen M-H, Shen Z-M, Bobin S, Kahn PC, Lipke PN. Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-agglutinin. Evidence for a yeast cell wall protein with multiple immunoglobulin-like domains with atypical disulfides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26168–26177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grigorescu A, Chen M-H, Zhao H, Kahn P, Lipke PN. A CD2-based model of yeast α-agglutinin elucidates solution properties and binding characteristics. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:105–113. doi: 10.1080/713803692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao H, Shen Z-M, Kahn PC, Lipke PM. Interaction of α-agglutinin and a-agglutinin, Saccharomyces cerevisiae sexual cell adhesion molecules. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2874–2880. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2874-2880.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loza L, Fu Y, Ibrahim AS, et al. Functional analysis of the Candida albicans ALS1 gene product. Yeast. 2004;21:473–482. doi: 10.1002/yea.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kamai Y, Kubota M, Kamai Y, et al. Contribution of Candida albicans ALS1 to the pathogenesis of experimental oropharyngeal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2002;9:5256–5258. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5256-5258.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaffin WL, Sogin SJ. Germ tube formation from zonal rotor fractions of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:771–776. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.771-776.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7329–7334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401648101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaur R, Domergue R, Zupancic ML, Cormack BP. A yeast by any other name: Candida glabrata and its interaction with the host. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ibrahim AS, Spellberg BJ, Avenissian V, et al. Vaccination with recombinant N-terminal domain of Als1p improves survival during murine disseminated candidiasis by enhancing cell-mediated, not humoral, immunity. Infect Immun. 2005;73:999–1005. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.999-1005.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spellberg BJ, Ibrahim AS, Avenissian V, et al. The anti-Candida albicans vaccine composed of the recombinant N terminus of Als1p reduces fungal burden and improves survival in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6191–6193. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6191-6193.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ibrahim AS, Spellberg BJ, Avanesian V, et al. The anti-Candida vaccine based on the recombinant N-terminal domain of Als1p is broadly active against disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3039–3041. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.3039-3041.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Spellberg BJ, Ibrahim AS, Avanesian V, et al. Efficacy of the anti-Candida rAls3p-N or rAls1p-N vaccines against disseminated and mucosal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:256–260. doi: 10.1086/504691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson A. The biology of mating in Candida albicans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:106–116. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Soll DR. Mating-type locus homozygosis, phenotypic switching and mating: a unique sequence of dependencies in Candida albicans. Bioessays. 2004;26:10–20. doi: 10.1002/bies.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Magee BB, Legrand M, Alarco AM, Raymond M, Magee PT. Many of the genes required for mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are also required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1345–1351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]