Abstract

A key factor in the biology of Francisella spp. is lipopolysac-charide (LPS). Francisella LPS has many unique structural properties and poorly activates proinflammatory responses due to its lack of interaction with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). The LPS of this organism can be modified by various carbohydrates including glucose, mannose and galactosamine, which affect various aspects of virulence. Spontaneously occurring colony variants of F. tularensis have altered LPS. This altered LPS may account for the novel phenotypes of these variants that include effects on susceptibility to killing by normal human serum, intracellular survival and animal virulence. Mutants devoid of O-antigen (directed mutants in O-antigen biosynthetic genes) show reduced intracellular survival and mouse virulence. Thus, this surface component is important in F. tularensis pathogenesis, and the inability of the LPS to alarm the immune system coupled with its frequent modification/alteration likely aid the success of this pathogen during human infection

Keywords: LPS, lipopolysaccharide, gray variant, phase variation, LPS modification, LPS structure, lipid A, O-antigen

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) is the primary constituent of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The structure of LPS includes a lipid portion (lipid A) that anchors it into the membrane, a polysaccharide core and an oligo- or polysaccharide extending from the core beyond the bacterial surface. LPS has been shown to be essential in most Gram-negative organisms likely due to its role in membrane integrity, and is a key factor in immune stimulation via its detection by host pattern recognition receptors.1

In many respects, the LPS of Francisella spp. is unique. Of critical importance is that the Francisella LPS lacks free phosphate moieties and exhibits very low endotoxicity. Because of the current advances in Francisella genetics and genomics, considerable new information regarding the LPS of this organism has been recently discovered. This new information relates to LPS structural variation between species and subspecies, intra-strain phase/antigenic variation and its role in virulence and immune recognition. This chapter will provide an up-to-date as well as historical perspective on these aspects of LPS biology in the Francisellae. Much of the information is currently unpublished but important to incorporate here, as it will form the basis for future studies in this field.

Structure of Francisella LPS (LIPID A, CORE, and O-ANTIGEN)

Lipid A

The genus Francisella tularensis consists of four subspecies: tularensis (Type A), holartica (Type B), mediasiatica, and novicida. The structure of lipid A isolated from two type B Francisella tularensis subspecies holartica strains (1547–57 and LVS) and F. novicida (U112) after growth at 37°C were elucidated using mass spectrometry (MS), gas chromatography, nuclear magnetic resolution (NMR) and chemical methods.2–4 In these studies, only the primary structures from the dominant molecular ions were elucidated. The base lipid A structure for all strains was similar and consisted of a β-(1,6)-linked diglucosamine disaccharide with amide-linked fatty acids at the 2 (3-OH C18) and 2′ (3-OH C18-O-C16) positions, and ester-linked fatty acids at the 3 (3-OH C18), but not the 3′ positions (FIG. 1). Additions to the base lipid A structure in F. holartica (1547–57) and F novicida included a single phosphate moiety at the 1 position of the reducing glucosamine residue (absent in the LVS strains and suggests a potential role in virulence). Interestingly, the 1-phosphate moiety was further substituted with the positively charged sugar, galactosamine 2 that was recently shown to be α-linked in F novicida by Wang et al.4 The functional outcome of galactosamine modification of lipid A, previously described as a component of total lipid A preparations from the oral pathogen, Selenomonas sputigena, is unknown.5

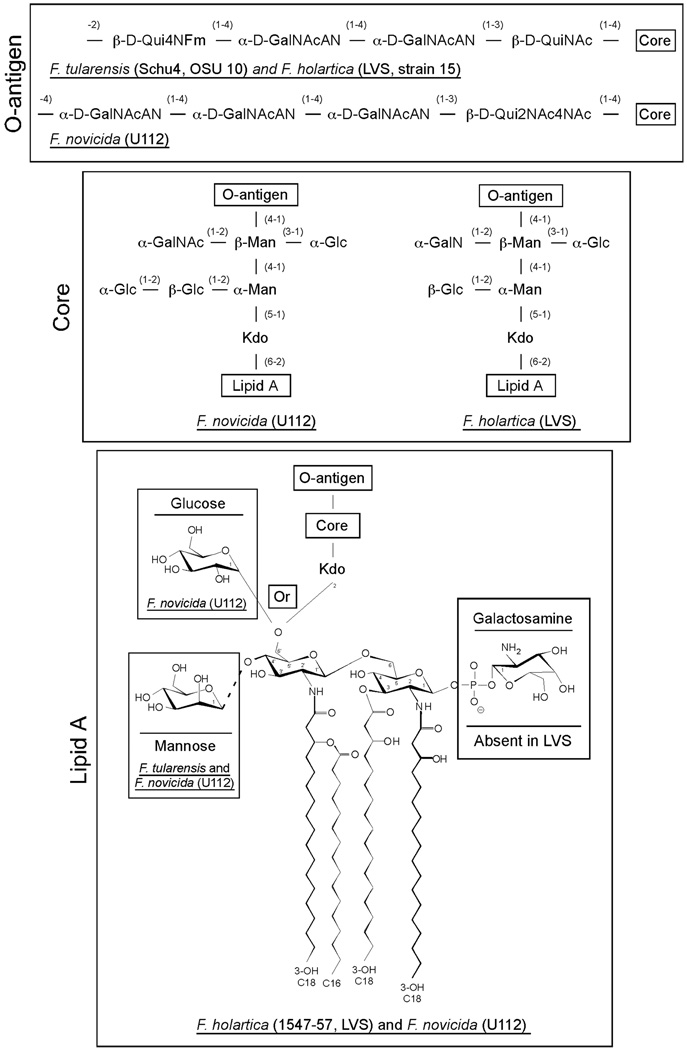

FIGURE 1.

Structure of lipid A, core, and O-antigen molecules synthesized by Fran-cisella tularensis subspecies tularensis, holartica, and novicida. The lipid A structure consists of a β-(1,6)-linked glucosamine disaccharide with amide-linked fatty acids at the 2- and 2′-positions, and ester-linked fatty acids at the 3-position. Lipid A carbohydrate modifications include the addition of galactosamine through the 1-position phosphate, man-nose at the 4′-position and glucose at the 6′position. Lipid A molecules that have glucose in their structure would not be modified by the addition of Kdo-core-O-antigen. Unless noted on the structure, modifications are present in all Francisella subspecies. Linkages of individual carbohydrate residues are shown. Core: Kdo = 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid; Man = mannose; Glc = Glucose; GalNAc = N-acetyl galactosamine. O-antigen = QuiN4Fm = 4,6-dideoxy-4-formamido-D-glucose; GalNAcAN = 2-acetamino-2-deoxy-D-galacturonamide; QuiNAc = 2-acetamino-2,6,dideoxy-D-glucose; Qui2NAc4NAc = 2,4,-diacetamino-2,4,6-trideoxy-D-glucose.

F. novicida lipid A was further modified by a mannose residue predicted to be at the 4′ position of the non-reducing glucosamine or by the addition of an α-linked glucose moiety at the 6′ position.4 Interestingly, Wang et al. demonstrated this unique modification in free lipid A, i.e extracted without hydrolysis, which results in the lack the usual Kdo, core, and O-antigen sugars.4 Furthermore, they suggest that over 95% of the lipid A recovered after Bligh-Dyer lipid extraction was present in the “free” form and suggests the presence of a novel system of LPS remodeling enzymes in the Francisellae. Finally, matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry of lipid A isolated from clinical and environmental strains of F. tularensis subspecies tularensis, holartica, and mediasiatica after growth on rich medium at 37°C were similar and suggests a common lipid A structure for all F. tularensis subspecies.6

Core

The structure of the core region isolated from the type B F holartica strain (LVS)3 and F. novicida (U112)7 after growth at 37°C was elucidated using MS and NMR techniques (FIG. 1). The core region is linked to lipid A through the eight-carbon sugar, 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo). The core structure from F. novicida is nearly identical to that of F. holartica, differing by the addition of an additional α-glucose residue attached to the β-Glc attached to the central inner core α-Man residue. (Note error in core structure3 – the α-Glc residue is shown on the α-Man instead of the β-Man residue). The core region of both strain backgrounds was shown to lack phosphate modifications and contain a single Kdo residue, suggesting the presence of a Kdo-specific hydrolase similar to enzymatic activity recently identified in membrane extracts from Helicobacter pylori.8

O-antigen

Since the original NMR structural characterization of the O-antigen region of LPS isolated from the F. holartica vaccine strain, strain 15 by Vinogradov et al. in 1991,9 the O-antigen structures of two additional type A F. tularensis strains (Schu S4 and OSU10),10,11 a second type B F. holartica strain (LVS),10,12 and F. novicida (U112)13 after growth at 37°C have been elucidated (FIG. 1). These data clearly show that the O-antigen from the Type A and B strains are identical in structure, whereas the structure of F. novicida O-antigen shares the same internal two carbohydrate residues (α-D-GalNAcAN- α-D-GalNAcAN), though differs for the outside two residues (α-D-GalNAcAN and β-DQui2NAc4NAc for F. novicida versus β-D-Qui4NFm and β-D-QuiNAc for Type A and B). Analysis of the O-antigen gene clusters from various Francisellae backgrounds confirms the structural analysis results. The O-antigen gene clusters for Schu4 and LVS are identical, as compared to that from F. novicida, which has fewer genes in the cluster and a lower G+C ratio.10,14

Identification and Regulation of Genes Involved in Lipid A Biosynthesis

Recently, six genes have been identified in F. novicida that encode enzymes required for the synthesis of the base lipid A structure1,15,16 (FIG. 2). These enzymes include two phosphatases (LpxE and LpxF, not present in E. coli), two dolichyl phosphate-mannose synthase-like enzymes (PmrF1 and PmrF2), one glycosyltransferase (PmrK), and a second early acyltransferases (LpxD2). All enzymes are highly conserved (>98% identity, at the amino acid level) in the four currently sequenced Francisella background strains: Schu S4 (Type A), LVS and OSU200 (Type B), and F. novicida (U112), thereby suggesting a conserved role for these enzyme homologs in overall Francisellae lipid A synthesis.

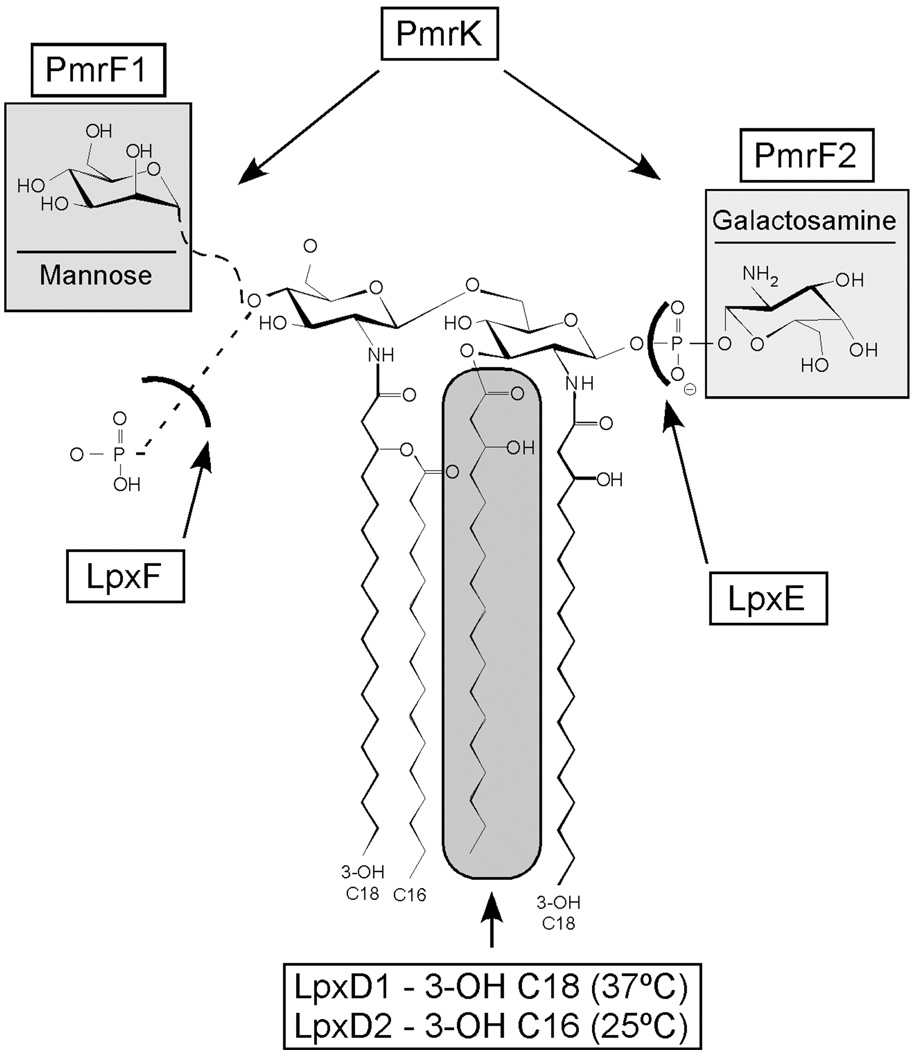

FIGURE 2.

Enzymes required for the synthesis of F. novicida lipid A. Genes identified i n F. novicida that encode enzymes required for the synthesis of the lipid A. These enzymes include two phosphatases (LpxE and LpxF), two dolichyl phosphate-mannose synthase-like enzymes (PmrF1 and PmrF2), one glycosyltransferase (PmrK), and a second hydroxyacyl acyltransferases (LpxD2).

The phosphatases, LpxE (FTN0416)17,18 and LpxF (FTN0295)19 remove the terminal phosphate moieties from either the 1- or 4′ position, respectively (www.Francisella.org). Expression cloning in E. coli identified LpxE enzymatic activity, however in F novicida, this activity is either inactive or rapid translocation of newly synthesized lipid A doesn’t allow for the removal of the 1-positon phosphate and galactosamine residue17 Recently, LpxF enzymatic activity was shown to be involved in the removal of the 4′-phosphate moiety from F. novicida lipid A. Interestingly, mutants lacking LpxF activity while retaining the 4′-phosphate moiety also retained the previously deacylated 3-hydroxyacyl fatty acid suggesting that the 4′-phosphate group must be removed before the 3′-hydroxyacyl fatty acid20

The dolichyl phosphate-mannose synthase-like enzymes, PmrF1 (FTN1403) and PmrF2 (FTN0545), are required for the transfer of mannose or galactosamine residues to bactoprenol phosphate on the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane.1 Individual genes were identified in F. novicida that were required for addition of galactosamine (pmrF2) or a second hexose predicted to be mannose (pmrF1) (R.K. Ernst, unpublished observations). This is in contrast to Salmonella typhimurium, which only has a single PmrF enzyme required for the addition of the positively charged sugar, aminoarabinose (∼30% identical to the either of the F. novicida PmrF orthologs).21 The addition of galactosamine to F. novicida lipid A was through the 1-position phosphate and a mutant in pmrF2 was shown to be attenuated in mice either by intradermal or aerosol routes of infection (R.K. Ernst, unpublished observations).

Mannose modification of F. novicida is predicted to be attached to the 4′-position of the non-reducing glucosamine of the lipid A backbone disaccha-ride and has been hypothesized to function as a replacement for the phosphate residue removed by LpxF. This modification has previously been described for lipid A isolated from the obligate predatory bacterium Bdellovibrio bacte-riovorus, Rhodomicrobium vannielii, and various purple sulfur phototrophic bacteria.22–25 Analysis of pmrF1 mutants showed this strain to be as virulent as wild type bacteria in mice by either route of infection described above. Finally, modification of lipid A by mannose was also observed in a temperature-dependent manner (i.e., increased mannose addition after growth at environmental temperatures <25°C) (R.K. Ernst, unpublished observation) in a subset of F. tularensis Type A clinical isolates but not F. holartica or F. mediasiatica isolates suggesting a potential role in environmental bacterial adaptation or survival.

The glycosyltransferase enzyme, PmrK (FTN0546) is required for the addition of both mannose and galactosamine to F. novicida lipid A on the outer leaflet of the inner membrane. In contrast to enzymatic activity from S. ty-phimurium or E. coli PmrK (∼24% identical to the F. novicida PmrK or-tholog),26 which transfers a single carbohydrate species (aminoarabinose) to the lipid A molecule, F. novicida PmrK interestingly has less substrate specificity. The F. novicida PmrK enzyme surprisingly has the ability to attach two different carbohydrate residues at either end of the base lipid A structure. A mutant in pmrK was shown to lack both lipid A modifications and had similar structure as lipid A isolated from the LVS vaccine strain. Finally, mutants in pmrK were shown to be attenuated in mice either by intradermal or aerosol routes of infection and provided protection against wild type F. novicida infection (R.K. Ernst, unpublished observation).

In addition to the essential LpxD1 (FTN1480) acyltransferase enzyme present as part of a four-gene operon (lpxB/lpxA/fabZ/lpxD),1,15 a second early acyltransferase; LpxD2 (FTN0200) was identified in F. novicida with homol-ogy to LpxD enzymes present in H. pylori and Campylobacter jejuni. This acyltransferase activity was shown to play a role in generating lipid A with shorter N-linked fatty acids normally present after growth at 25°C as compared to growth at 37°C (3-OH C16 versus 3-OH C18, respectively). Using negative electrospray ionization with a linear ion trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance hybrid mass spectrometer, the Ernst laboratory has recently identified a high degree of structural heterogeneity in F. novicida lipid A that suggests a role for multiple LpxD enzymes in temperature-dependent membrane remodeling. Finally, though normally essential and required for membrane integrity, no growth defect was observed for LpxD2 deficient enzyme mutants after growth in rich medium either at 25°C or 37°C (R.K. Ernst, unpublished observation).

Blue Versus Gray: Lipopolysaccharide Phase/Antigenic Variation

Phenotypic diversity in F. tularensis colony morphology has been known for some time. First reported in 1951 by Eigelsbach,27 spontaneously appearing colony variants of F. tularensis Schu S4 were identified on the basis of appearance under oblique light (blue or gray color to the colony), reaction to acriflavine agglutination (positive or negative), and colony morphology (rough or smooth). Many different colony types were identified. The characteristics of these variants were relatively stable when sub-cultured, but could be shown to vary back to the original colony morphotype. Changes in virulence and immunogenicity were associated with colony variation. In general, rough and/or gray colony variants were less virulent and less immunogenic (LD100 >107), while blue/smooth variants were more virulent and produced a robust immunogenic response. In addition, the gray variants often exhibit a small colony morphology and grow slightly slower than the blue “wild type” strain. The appearance of variants was dependent on the age of the culture, pH, inoculum size, and one or more as-of-yet unknown factors present in spent culture filtrates. This information established a set of culturing methods that could be used to minimize or increase the appearance of F. tularensis variants. In general, the longer the time of culture, the greater the frequency of blue to gray transition. Thus, blue/smooth colonies represent the “wild type” F. tularensis strain while the gray/rough represents the variant. While this phenomenon in Francisella has been termed phase variation (the off/on of a phenotype), this may more accurately be labeled antigenic variation with regard to some of the specific alterations described in these strains below.

With regard to the LVS strain, only two distinct colony variants (blue and gray, FIG. 3) were described by Eigelsbach when this vaccine strain was grown on agar and observed with obliquely transmitted light.28 These variants were purified, maintained and tested in animals to determine the relative virulence and immunogenicity. As with the Schu S4 strain described above, the LVS blue variant was more virulent and immunogenic than the gray variant. The mouse sub-cutaneous LD50 for the blue variant was determined to be 105 colony-forming units (CFU) while the gray was 109 CFU. These variants were evaluated in mice and guinea pigs as a vaccine. Approximately ninety percent of mice inoculated subcutaneously with 100–1000 cfu’s of the blue variant survived vaccination. Sixty-seven to eighty-three percent of that population survived at least 60 days post challenge with 100–1000 LD50’s of F. tularensis Schu S4. One hundred percent of mice immunized with 108 gray variants survived vaccination, but none were protected when challenged with Schu S4. Guinea pigs were less susceptible to LVS blue variants, and all animals inoculated with 108 organisms survived. One hundred percent of guinea pigs challenged with >10 LD50’s of Schu S4 survived for 15 days, but the percentage dropped to between 17 and 33 at 60 days. A dose of 109 of the gray variant did not result in death in the guinea pigs and did not protect any animals against >10 LD50’s of Schu S4 challenge.

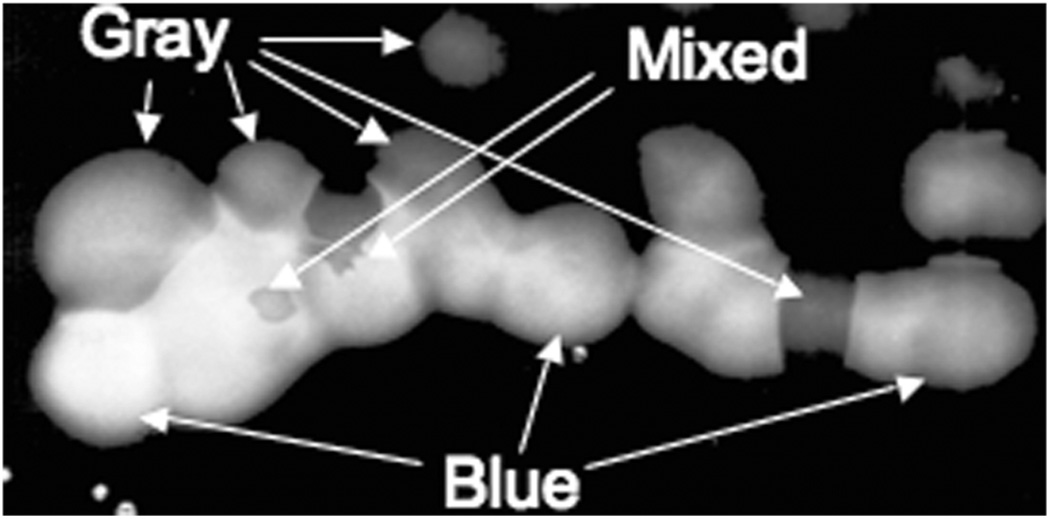

FIGURE 3.

Blue and gray colony variants of F. tularensis LVS. Black and white picture taken under an oblique light source illumination of bacterial colonies on the agar surface. Bacteria were grown for ∼48 hrs in T-soy broth-cysteine (TSB-C) batch culture followed by plating onto the surface of TSB-C agar. The microscope and light source used were as described by Eigelsbach.26 Blue, gray and mixed colonies are noted. Courtesy of Brian Bell.

Many techniques have been employed since the 1950s to examine such colony variation with none being embraced as foolproof and/or simple to perform. Methods have included viewing the bacteria on chocolate agar plates or on cysteine heart agar (CHA) with or without 5% fresh sheep blood by eye or with a dissecting microscope set up with a specific mirror and oblique light source ala Eigelsbach. Most recently, a fluorescent activated cell sorter (FACS) approach has been described which will separate gray variants without O-antigens but not all gray variants. No matter the approach, it is not simple to see such variants, and takes patience and experience to become skilled at doing so.

Although it is not obvious what the entire repertoire of alterations are in a gray variant, it is clear that LPS plays a role. From the outset, it should be made clear that there is not a single LPS structure associated with the gray variant. Thus, as will be apparent from the results discussed below, gray variants are not uniform in genetic structure or in their phenotypes (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic comparisons between F. tularensis variants

| Strain | Colony Morphology | LD50a | Intramacrophage Survivalb | Serum Sensitivity | Protective vs. Schu S4 Challengec | O-Antigen | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVS | Large, blue, smooth | <10 | Survives well | Resistant | Protective | Complete | 29,30 |

| LVSG | Small, gray, smooth | >103 | Defective | Sensitive | Not protective | Complete | 31, J. Gunn, Unpublished Observation |

| LVSGD | Small, gray, smooth | >105 | Defective | Sensitive | Not protective | Absent | 32 |

| LVSGT | Large, transparent, gray? | ND | Defective | Sensitive | ND | Present but Reduced Length | J. Cannon, Personal Communication |

| Schu S4 | Large, blue, smooth | <10 | Survives well | Resistant | NA | Complete | 27,28 |

| Schu S4NS | Small, non-smooth, gray | 107 | ND | ND | Not protective | ND | 27 |

Routes of delivery of the reported LD50s are as follows: LVS (i.p.), LVSG (i.n.), LVSGD (s.q.), Schu S4 (i.p.), Schu S4NS (i.p.).

Macrophages (primary or cell lines) used are as follows: LVS (rat, mouse, and human primary or cell lines), LVSG (rat, mouse [reduced proliferation is to a lesser extent than in other macrophage types], and human primary or cell lines), LVSGD (J774.1), LVSGT (THP-1).

The route of administration is as described under the LD50 column, and the Schu S4 was via the same route as the variant strain. The dosages of Schu S4 were variable but the results reported in this table are accurate for 10–100 LD50S as the dose.

In 1996, Cowley et al. identified LVS variants, LVSG (gray) and LVSR (rough).31 These variants were identified via colony opacity and morphology, with the LVSG strain being further characterized. Revertants of these pheno-types were identified. The blue to gray transition occurred with a dramatically increased frequency in stationary phase bacteria as well as after passage through animals or in vitro through macrophages. The LPS of this mutant was examined with monoclonal antibodies to the F. novicida LPS O-antigen, which recognizes only this subspecies. The antibody recognized the LVSG strain, suggesting an alteration of the O-antigen in the gray variant LVSG. The LVSG LPS and lipid A was also shown to be more bioactive, as they induced more nitric oxide (NO) activity from rat peritoneal macrophages. Because the LVSG lipid A itself demonstrated the ability to induce more NO, this implied that this gray variant also had an altered lipid A structure. Studies have also clearly shown that this strain is more sensitive to killing by normal human serum and binds larger amounts of the complement component C3 to its surface compared to wild type F. novicida (J.S. Gunn, unpublished observation). Studies are underway to define the LPS structure of the LVSG variant as well as more global approaches (DNA microarray, 2-D mass spectrometry fingerprinting) to ascertain other possible phenotypic alterations in this strain and to identify the putative genetic basis of the variation. Initial analysis of the LVSG structure demonstrates no major structural alterations in the O-antigen and lipid A that would be predicted from the data of Cowley et al. (J.S. Gunn, unpublished observation). Subtle alterations in the LPS (e.g., sugar modifications to the lipid A, acetylation of the O-antigen) may be present and are the current focus of attention in these studies.

In 2005, a different gray variant was characterized in the Titball laboratory.32 This F. tularensis LVS variant had an altered LPS, but in this case the defect was clear: the O-antigen was not present. Such gray variants appear identical to those recovered from DynPort Vaccine Company LLC cultures of LVS that have been characterized by the Gunn laboratory, and will henceforth be called LVSGD (DynPort). Thus, it is clear that gray variants can have different LPS structures, demonstrating that the LPS structure is not the determining factor in the blue to gray variation. Like the LVSG strain, the LVSGD strain grew slower than the LVS and appeared at an increased rate in stationary phase cells. Compared to the wild type LVS “blue variant”, these LVSGD gray variants showed a diminished ability to survive in macrophages and had reduced virulence in the mouse. As has been shown by Eigelsbach with gray variants, immunization of mice with LVSGD bacteria did not induce protective immunity towards fully virulent F. tularensis.

A third type of F. tularensis LVS variant has been described by the opacity of the colonies on solid agar (transparent as opposed to the opaque “wild type” strain, J. Cannon, unpublished observation). Such variants have been demonstrated to possess a truncated LPS O-antigen, thus an intermediate LPS phenotype between the LVSG and LVSGD. Henceforth this strain will be called LVSGT. This variant was more sensitive to killing by human sera and survived less well in human macrophage-like THP-1 cells. Surprisingly, these variants demonstrated increased resistance to H202 and polymyxin B, suggesting that they may have a selective advantage in certain microenvironments in the host.

The above description of the gray variants points to the fact that these variations occur likely in all F. tularensis subspecies and affect intracellular survival, resistance to innate and possibly adaptive immune components, and the protective capacity of vaccine preparations. Thus, this variation is an important consideration in live, whole cell vaccine preparations. Unfortunately, the phe-notypes of the variants cannot yet be directly attributed to the observed LPS alterations until the genetic/cellular basis of variation is discovered and characterized. If the basis of the variation is genetic, it may be possible to lock F. tularensis in the “blue” form and eliminate the concerns over this variation.

LPS-Mediated Inflammatory Responses to Francisella LPS

All animals have innate immune mechanisms for recognizing prokary-otic pathogens without the delays inherent in de novo antigen-dependent re-sponses.33,34 These mechanisms are induced in response to bacterial molecules that the host recognizes as foreign, such as those signaling pathogen colonization and invasion of host tissues. The surface of Gram-negative bacteria is composed of numerous Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, including flagella, lipoproteins, peptidoglycan, and LPS. Among the best characterized and most important of these molecules is LPS, the major component of the Gram-negative bacterial envelope. Lipid A, or endotoxin, is the sole portion of LPS recognized by the innate immune system.

Recognition of LPS occurs largely through the mammalian LPS receptor, the TLR4-MD2-CD14 complex, which is present on many cell types including macrophages and dendrite cells,35–40 whereas, epithelial cells do not express CD14; hence respond only to much higher concentrations of LPS (via CD14-independent pathways). Recognition of lipid A also requires an accessory protein, LPS binding protein (LBP), which converts oligomeric micelles of LPS to a monomer for delivery to CD14, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored, high affinity membrane protein which can also circulate in a soluble form. CD14 alone does not stimulate innate microbial immune responses, because its GPI anchor does not span the plasma membrane. Instead, TLRs which contain leucine rich repeat (LLR) domains, bind CD14-associated bacterial lig-ands and transduce the microbial recognition event across the membrane. In humans, TLR4 (with accessory protein termed MD-2) is primarily responsible for recognition to Gram-negative bacteria and more specifically for responses to lipid A. How this complex recognizes lipid A and signals across the plasma membrane is still not completely understood. Finally, association of the TLR cytoplasmic tail with MyD88 and IRAK triggers a phosphorylation cascade (via TRAF6, NIK and IKK) that results in the phosphorylation (and subsequent degradation) of IkB and translocation of NFkB to the nucleus. There, NFkB initiates transcription of various gene products important in inflammation including; synthesis and secretion of cytokines and chemokines, induction of adhesion molecules, migration of host cells, phagocytosis and killing of microbes within membrane-bound vacuoles and synthesis and secretion of cationic antimicrobial peptides.

LPS structure and stimulatory potential varies between bacterial species. Lipid A from the enteric commensal and occasionally pathogenic E. coli is highly immune stimulatory, even at low doses. However, in several in vivo and in vitro assays, LPS isolated from F. tularensis subspecies remarkably displayed little to no endotoxic properties: specifically it was neither a lymphocyte stimulus nor a lymphocyte mitogen. In addition, F. tularensis subspecies LPS also displayed little to no endotoxic properties in either galactosamine-treated mice, by limulus assay (a standard for determining LPS endotoxin potential), or after aerosolization in mice, and do not stimulate mononuclear cells to release cytokines of nitric oxide.6,41–44

Several properties of F. tularensis subspecies lipid A are uncommon among Gram-negative bacteria.35 First, the absence of a phosphate at the 4′ position on the non-reducing glucosamine backbone dimer likely contributes to the lack of stimulatory activity, as demonstrated for monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL).45–47 MPL is a chemically dephosphorylated Salmonella lipid A molecule that is of low endotoxic activity, and has recently been used as a vaccine adjuvant.46,48 Second, Francisellae lipid A is hypo-acylated (tetra-acylated) and contains longer acyl side chains of 16–18 carbons in length,2,3,19as compared highly inflammatory lipid A from enteric bacteria that is normally hexa-acylated containing acyl side chains of 12 to 14 carbons in length. Third, F. tularensis LPS or lipid A does not act as an antagonist for either human or mouse TLR4-mediated innate immune responses and was recently shown by Barker et al. that F. holartica LVS LPS did not bind LBP or the closely related polymorpho-nuclear granule protein, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI). Taken together, these unique F. novicida lipid A structural modifications result in the inability to bind to TLR4 or other components of the LPS receptor complex and result in the failure to initiate a downstream innate immune response.

Role Of O-Antigen and Lipid A Modifications in Virulence

Alterations in the structure of LPS has been shown to affect virulence/virulence phenotypes of various pathogens. For example, loss of the O-antigen generally results in increased susceptibility to killing by membrane active compounds such as serum and antimicrobial peptides, reduced intracel-lular survival and decreased virulence,1 The above-mentioned work relating to the loss of virulence of gray variants suggests that O-antigen plays a role in Francisella pathogenesis. Recent studies have specifically addressed this topic.

Directed mutations within the O-antigen gene cluster have been performed in F. tularensis Schu 4, F. novicida and F. tularensis LVS. These mutations (most in the first gene [wbtA] of the O-antigen biosynthetic cluster) all resulted in the loss of O-antigen on the LPS and dramatically reduced serum resistance and mouse virulence.14,49 While the F. tularensis Schu S4 and LVS O-antigen mutations also reduced survival in murine macrophage cell lines, no effect on intracellular survival was observed for F. novicida. Studies with human cells have yet to be reported and could possibly yield different results. This work has also shed some light on the protective capacity of LPS in vaccine approaches, but this work will be reviewed in Chapter 12 of this book.

Conclusions And Outlook

The intense study of Francisella LPS, particularly the genetic aspects of LPS biosynthesis and modification, has occurred only recently. The very recent availability of genome sequences of the various Francisella subspecies has greatly aided this analysis. Such analysis has lead to the identification of Francisella orthologs of lipid A, core and O-antigen biosynthetic genes and the comparisons of these genes between the subspecies. Also aiding this work has been the seminal work over the years that has defined the structure of the LPS in various strains and subspecies. Thus, the unique marriage of structural biology and biochemistry with genomics has provided a windfall of information regarding the Francisella LPS.

It is clear from the studies described above that LPS is a key virulence factor of Francisella spp., as several O-antigen and lipid A modification mutants are attenuated in the mouse model. In addition, lipid A biosynthetic enzymes are essential in Francisella as is found in most Gram-negative bacteria. Colony variants that have reduced virulence and diminished protective capacity as vaccines also possess altered LPS structure, which further suggests a role for LPS in pathogenesis. Thus, this knowledge suggests several targets for therapeutic intervention of Francisella pathogenesis. This approach has been used with success, at least in the laboratory, in other Gram-negative pathogens.50 Such therapeutics might provide an advantage over vaccine strategies as they might be used for a more targeted population and may provide treatment post-exposure.

With regard to vaccine approaches to prevent tularemia, the vaccine that has been used most extensively in humans worldwide and that is in the current FDA pipeline with clinical trials in the US in the LVS.51,52 As described, variants (commonly gray) of this strain clearly appear that are not protective against virulent Type A or Type B challenge. In addition, it is now clear that a single variant type does not exist, and that there are multiple types of “gray variants.” The growth conditions of the culture can limit the development of gray variants, such as avoiding lengthy batch cultures in which the bacteria are in stationary phase for extended times. Historically, gray variants have been a problem in Francisella vaccine lots, as evidenced by the Salk Institute’s vaccine runs in the 1960’s under IND 157 in which a large proportion of the organisms in the vaccine prep gave rise to gray colonies. If there is a genetic basis to the observed colony variation, which is likely for some (e.g., LVSGD) but not all colony variants, it may be possible to lock strains in a blue colony type. However, until we gain a more complete understanding of Francisella colony variation- at a molecular level understanding both how and why this variation occurs, such phase locked variants are unattainable.

Continued study of Francisella LPS will undoubtedly bring about considerable new information and additional therapeutic targets to the field. As technology and genetic analysis of Francisella spp. continues to advance, further details will emerge revealing a more comprehensive model of the biosynthesis and variation of Francisella LPS and its contribution to human disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Evgeny Vinogradov in ensuring the validity of the structural information presented, Brian Bell for his contributions to the section concerning the early work of Eigelsbach and in his knowledge of the gray variants, Shilpa Soni for her work in characterizing the phenotypes of various gray variants, and Duangjit Kanistanon for identification and characterization of enzymes involved in lipid A biosynthesis. The authors wish to thank the Region X “Northwest” Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Consortium (NIH Award 1-U54-AI-57141, RKE) and the Region V “Great Lakes” Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Consortium (NIH Award 1-U54-AI-057153, JSG) for generous funding and support.

References

- 1.Trent MS, et al. Diversity of endotoxin and its impact on pathogenesis. J. Endotoxin. Res. 2006;12:205–223. doi: 10.1179/096805106X118825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips NJ, et al. Novel modification of lipid A of Francisella tularensis. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5340–5348. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5340-5348.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinogradov E, Perry MB, Conlan JW. Structural analysis of Fran-cisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:6112–6118. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, et al. Structure and biosynthesis of free lipid A molecules that replace lipopolysaccharide in Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14427–14440. doi: 10.1021/bi061767s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumada H, et al. Chemical and biological properties of lipopolysaccharide from Selenomonas sputigena ATCC 33150. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 1997;12:162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajjar AM, et al. Lack of in vitro and in vivo recognition of Francisella tularensis subspecies lipopolysaccharide by Toll-like receptors. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6730–6738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00934-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinogradov E, Perry MB. Characterization of the core part of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen of Francisella novicida (U112) Carbohydr. Res. 2004;339:1643–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stead C, et al. A novel 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) hydrolase that removes the outer Kdo sugar of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:3374–3383. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3374-3383.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinogradov EV, et al. At Structure of the O-antigen of Francisella tularensis strain 150. Carbohydr. Res. 1991;214:289–297. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)80036-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prior JL, et al. Characterization of the O antigen gene cluster and structural analysis of the O antigen of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52:845–851. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thirumalapura NR, et al. Structural analysis of the O-antigen of Fran-cisella tularensis subspecies tularensis strain OSU 10. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;54:693–695. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conlan JW, et al. Mice vaccinated with the O-antigen of Francisella tu-larensis LVS lipopolysaccharide conjugated to bovine serum albumin develop varying degrees of protective immunity against systemic or aerosol challenge with virulent type A and type B strains of the pathogen. Vaccine. 2002;20:3465–3471. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinogradov E, et al. Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen of Francisella novicida (U112) Carbohydr. Res. 2004;339:649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas RM, et al. The immunologically distinct O antigens from Fran-cisella tularensis subspecies tularensis and Francisella novicida are both virulence determinants and protective antigens. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:371–378. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01241-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raetz CR, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trent MS. Biosynthesis, transport, and modification of lipid A. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2004;82:71–86. doi: 10.1139/o03-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, et al. MsbA transporter-dependent lipid A 1-dephosphorylation on the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane:topography of Francisella novicida LpxE expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49470–49478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409078200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran AX, et al. The lipid A 1-phosphatase of Helicobacter pylori is required for resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:4531–4541. doi: 10.1128/JB.00146-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, et al. Expression cloning and periplasmic orientation of the Francisella novicida lipid A 4′-phosphatase LpxF. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9321–9330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, et al. At Attenuated virulence of a Francisella mutant lacking the lipid A 4′-phosphatase. PNAS. 2006;104:4136–4141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611606104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunn JS, et al. Genetic and functional analysis of a PmrA-PmrB-regulated locus necessary for lipopolysaccharide modification, antimicrobial peptide resistance, and oral virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6139–6146. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6139-6146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwudke D, et al. The obligate predatory Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus possesses a neutral lipid A containing alpha-D-Mannoses that replace phosphate residues:similarities and differences between the lipid As and the lipopolysac-charides of the wild type strain B. bacteriovorus HD100 and its host-independent derivative HI100. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:27502–27512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weckesser J, Mayer H. Different lipid A types in lipopolysaccharides ofphototrophic and related non-phototrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1988;4:143–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holst Oetal. Structural studies on the phosphate-free lipid A of Rhodomi-crobium vannielii ATCC 17100. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983;137:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meissner J, et al. Lipopolysaccharides of Thiocystis violacea, Thiocapsa pfennigii, and Chromatium tepidum, species of the family Chromatiaceae. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:3217–3222. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3217-3222.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trent MS, et al. An inner membrane enzyme in Salmonella and Escherichia coli that transfers 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to lipid A:induction on polymyxin-resistant mutants and role of a novel lipid-linked donor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eigelsbach HT, W Braun, Herring RD. Studies on the variation of Bacterium tularense. J. Bacteriol. 1951;61:557–569. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.5.557-569.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eigelsbach HT, Downs CM. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J. Immunol. 1961;87:415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elkins KL, et al. Minimal requirements for murine resistance to infection with Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:3288–3293. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3288-3293.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anthony LD, Burke RD, Nano FE. Growth of Francisella spp. in rodent macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:3291–3296. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3291-3296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowley SC, S.V Myltseva, Nano FE. Phase variation in Francisella tularensis affecting intracellular growth, lipopolysaccharide antigenicity and nitric oxide production. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:867–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartley G, et al. Grey variants of the live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis lack lipopolysaccharide O-antigen, show reduced ability to survive in macrophages and do not induce protective immunity in mice. Vaccine. 2006;24:989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akira S, S. Uematsu OTakeuchi. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radtke AL, O′Riordan MX. Intracellular innate resistance to bacterial pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 2006;811:1720–1729. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyake K. Innate recognition of lipopolysaccharide by Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker LC, et al. The expression and roles of Toll-like receptors in the biology of the human neutrophil. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;77:886–892. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis E, Sousa C. Toll-like receptors and dendritic cells:for whom the bug tolls. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyake K. Endotoxin recognition molecules, Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Espevik T, et al. Cell distributions and functions of Toll-like receptor 4 studied by fluorescent gene constructs. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;35:660–664. doi: 10.1080/00365540310016493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ancuta P, et al. Inability of the Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide to mimic or to antagonize the induction of cell activation by endotoxins. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:2041–2046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2041-2046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole LE, et al. Immunologic consequences of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain infection:role of the innate immune response in infection and immunity. J. Immunol. 2006;176:6888–6899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandstrom G, et al. Immunogenicity and toxicity of lipopolysaccharide from Francisella tularensis LVS. FEMS Microbiol. Immunol. 1992;5:201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Telepnev M, Golovliov I, Sjostedt A. Francisella tularensis LVS initially activates but subsequently down-regulates intracellular signaling and cytokine secretion in mouse monocytic and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Microb. Pathog. 2005;38:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldridge JR, Crane RT. Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) formulations for the next generation of vaccines. Methods. 1999;19:103–107. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Persing DH, et al. Taking toll:lipid A mimetics as adjuvants and im-munomodulators. Trends. Microbiol. 2002;10:S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ulrich JT, Myers KR. Monophosphoryl lipid A as an adjuvant. Past experiences and new directions. Pharm. Biotechnol. 1995;6:495–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldridge JR, et al. Taking a Toll on human disease:Toll-like receptor 4 agonists as vaccine adjuvants and monotherapeutic agents. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:1129–1138. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raynaud C, et al. Role of the wbt locus of Francisella tularensis in lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biogenesis and pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:536–541. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01429-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coggins BE, et al. Structure of the LpxC deacetylase with a bound substrate-analog inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:645–651. doi: 10.1038/nsb948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conlan JW. Vaccines against Francisella tularensis-past, present and future. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2004;3:307–314. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oyston PC, Quarry JE. Tularemia vaccine:past, present and future. Antonie. Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;87:277–281. doi: 10.1007/s10482-004-6251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]