Abstract

When faced with interpersonal conflict, older adults report using passive strategies more often than do younger adults. They also report less affective reactivity in response to these tensions. We examined whether the use of passive strategies may explain age-related reductions in affective reactivity to interpersonal tensions. Over eight consecutive evenings, participants (N = 1031, 25 – 74 years-old) reported daily negative affect and the occurrence of tense situations where they had an argument or avoided an argument. Older age was related to less affective reactivity when people decided to avoid an argument but was unrelated to affective reactivity when people engaged in arguments. Findings suggest that avoidance of negative situations may largely underlie age-related benefits in affective well-being.

Keywords: emotion, aging, stressor reactivity, emotion regulation, well-being

Now You See it, Now You Don't: Age Differences in Affective Reactivity to Social Tensions

Social relationships are strongly tied to affective well-being. Higher levels of social support are related to lower levels of negative affect and decreased reactivity to stressful life events (e.g., Cohen & Wills, 1985). The benefits of social networks, however, are not without costs. Relationships can include conflict situations – arguments or potential arguments that create tension. These conflicts can occur under the best of social circumstances, as evidenced by the occurrence of disagreements among even happily married couples (e.g., Story, Berg, Smith, Beveridge, Henry, & Pearce, 2007). When conflicts occur, they lead to increases in negative feelings and physiological reactivity (Heffner, Kiecolt-Glaser, Loving, Glaser, & Malarkey, 2004; Levenson, Carstensen, & Gottman, 1994; Rook, 2001).

Although adults of all ages experience conflict, they do not respond to these situations uniformly (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003). Older adults, for example, report less emotional distress in response to social tensions than do younger and middle-aged adults (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003). In addition, older adults often report using more passive emotion-regulation strategies, such as ignoring or walking away from a situation; younger and middle-aged adults, in contrast, are more likely to endorse active strategies, such as direct confrontation (Birditt et al., 2005; Blanchard-Fields, Mienaltowski & Seay, 2007). Age-related decreases in affective distress may at first seem puzzling given age differences in coping styles. Active strategies are often associated with positive emotions and personality constructs related to positive emotions (such as optimism and extraversion), whereas behavioral disengagement is often linked to negative outcomes, such as lower control and greater anxiety (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Yet, experts agree that passive strategies are often the best option for interpersonal problems (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2007). Indeed, the greater use of passive strategies among older adults may be one reason why they report less affective reactivity in response to interpersonal tensions than do younger adults. The following study examined age differences in affective reactivity in response to two different social situations: one where people actively engaged in an argument and another where people opted for a strategy of disengagement from a tense social situation.

Age differences in affective responses to interpersonal conflict

Humans are social creatures who have an inherent need to feel a sense of belonging with others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). As such, age differences in emotion regulation strategies have often been studied in the context of social relationships. Social ties are linked to positive and negative emotional experiences across the lifespan (Antonucci, Langahl, & Akiyama, 2004). Higher levels of social support, both actual and perceived, are related to higher levels of affective well-being for people of all ages (Birditt et al., 2005; Cohen & Wills, 1985). Negative social encounters, in contrast, are associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and affective distress (Rook, 2001). Understanding how people regulate their emotions within social experiences, then, provides information for understanding age differences in affective well-being.

When asking younger and older adults about the emotions they experience during social interactions, the reports of older adults are often more positive than those of younger adults. For example, one study had mothers and their adult daughters engage in a cooperative laboratory task and then afterwards report the emotions they experienced during this task (Lefkowitz & Fingerman, 2003). Older mothers reported fewer negative emotions than did their adult daughters. When recalling social interactions with family members during the previous week, older adults also report higher levels of positive affect and lower levels of negative affect than younger adults (Charles & Piazza, 2007). Even when interpreting a negative situation, the reports of older adults are more positive compared to their younger counterparts (Story et al., 2007). In one study, for example, middle-aged and older spouses were asked to discuss a topic of contention. Older spouses rated their partners more positively than did middle-aged couples, and more positively than objective ratings would suggest (Story et al., 2007).

Age differences in behavioral responses to interpersonal tensions

Older adults report encountering fewer interpersonal tensions across the course of a week than do younger adults (Birditt, Fingerman, & Almeida, 2005). Although these age-related reductions may stem from a number of reasons, one possibility is that older adults engage in emotion regulation strategies that enable them to avoid these tensions. This antecedent emotion-focused strategy-- termed situation selection-- is arguably the best emotion regulation tactic, because potentially distressing situations are avoided altogether (Gross, 1998). When avoidance is not possible, however, people can use situation modification strategies to limit further exposure to the noxious event.

Research suggests that older adults engage in situation modification emotion regulation strategies to a greater extent than do younger adults. In comparison to younger adults, older report are more likely to report using passive strategies when confronted with interpersonal conflict with friends and family members, such as disengaging from a situation by not arguing with someone or waiting for the problem to pass (Birditt & Fingerman, 2005; Birditt et al., 2005; Blanchard-Fields, 2007). When asked about motivations underlying how they responded to a negative interpersonal exchange, older adults reported that their responses were motivated by goals to preserve harmony and avoid tension with the individual more than other types of goals, such as getting the person to change (Sorkin & Rook, 2006). These more passive strategies do not appear to be a method of last resort, because older adults recommend them to others who encounter negative social situations and regard them as the best course of action (Charles, Carstensen, & McFall, 2001). Passive responses are also identified as most effective by expert raters when used in response to conflict with close social partners (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2007). Moreover, older adults who report goals of preserving goodwill in response to a tense interpersonal exchange, as opposed to goals such as getting the person to change, report the lowest levels of emotional distress and the highest perceived success in achieving this goal in response to the negative interpersonal exchange (Sorkin & Rook, 2006).

Researchers have offered several reasons to explain why older adults engage in less active strategies when faced with social conflict. Socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen et al., 1999) posits that age is associated with the realization that time left in life is growing shorter. When faced with this diminished temporal horizon, older adults shift their priorities to optimize positive experiences. For younger adults, emotions are not as highly prioritized as goals that include gathering information from the environment to plan for and implement in the future. For this reason, younger adults are more focused on knowledge-related goals and may pursue them in social situations at the cost of emotional well-being. In contrast, older adults are more likely to choose strategies to enhance or maintain immediate emotional well-being based on their motivational goals (Carstensen et al., 1999; Sorkin & Rook, 2006). Avoiding negative situations, then, may be prioritized over other types of activities and employed more readily by older adults than younger adults (Charles & Carstensen, 2007).

Years of experience coupled with knowledge about social partners are additional reasons why older adults may choose less confrontational approaches when faced with interpersonal problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). After years of navigating through social and non-social situations, people understand what bothers them, what they enjoy, and the strategies that serve to minimize negative experiences and maximize positive ones. Thus, the motivation to prioritize emotion regulation, as described by socioemotional selectivity theory, and the experience garnered through time already lived enable older adults to engage in proactive emotion regulation strategies that include thoughts and behaviors directed toward avoiding negative situations.

The current study

Older adults recommend engaging in more passive emotion regulation strategies when faced with interpersonal conflict compared to younger adults (Charles et al., 2001; John & Gross, 2004), but researchers have yet to examine age differences in affective reactivity to situations involving these passive strategies. The current study examined age differences in affective reactivity to two types of tense social experiences. We defined affective reactivity as the change in level of affect on a day when a stressor occurs compared to the normative level of negative affect when a stressor is not present. Statistically, this change in affect is measured by a slope score (i.e., parameter estimate) that represents the degree of change in affective distress that occurs on days when a stressor is present compared to days when a stressor is absent. Age differences in affective reactivity were examined in response to two types of naturally occurring negative social situations: those where people reported engaging in an argument or disagreement with another person, and those where people could have involved themselves in an argument but actively chose to avoid the situation.

We hypothesized that older age would be associated with less affective reactivity in social situations where people actively disengaged from a negative social encounter. We based our hypothesis on age-related changes in motivation as predicted by socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen et al., 1999) and from age-related increases in social expertise (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2007). We further predicted that age differences in affective reactivity in response to situations where people disengaged from a negative interaction (that is, they could have argued but instead decided to avoid the disagreement) would be more pronounced than a situation where they actually had an argument. We predicted that when people had an argument age differences would be attenuated because an argument represents a situation where goals of older adults to avoid negative experiences (Charles & Carstensen, 2007) were not achieved, and preferences to avoid negative situations (cf. Blanchard-Fields, 2007) were not realized.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants

Data from the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) were used for the present study. The NSDE includes a subset of participants from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), which is a telephone and mail survey study of 3,032 nationally representative adults between 25-74 years of age (for more information on the MIDUS, see Brim, Ryff & Kessler, 2004). Of the 1,242 original randomly selected MIDUS respondents, 1,031 (562 women, 469 men) chose to participate, resulting in a response rate of 83%.

On average, participants in the NSDE were 47.3 years of age (SD = 13.2). Approximately half of the NSDE sample was female (54%) and over half of the sample had at least a high school degree or the equivalent (62%). The NSDE sample was predominantly Caucasian (90%) with a small subsample of African Americans (6%). The remaining people were from other racial groups or declined to state their ethnicity.

Procedure

The NSDE study included 8 consecutive daily telephone interviews where respondents were asked about their daily experiences. All NSDE interviews were conducted between March 1996 and April 1997. Although daily interviews may increase the risk of self-monitoring and potentially disrupt normal patterns of daily experiences, this procedure is less disruptive than study designs that involve several interviews throughout the day (see review by Tennen, Suls, & Affleck, 1991). For each of the eight evenings, participants reported their emotional well-being and the events of their day. They were asked specifically about seven different types of stressors: 1) argument or disagreement (argument tensions), 2) avoidance of an argument or disagreement (avoided arguments), 3) work or school stressor, 4) home stressor, 5) discrimination, 6) network stressor (i.e., a stressful event that happened to someone close to the participant but not directly to the participant), and 7) any other stressor. Participants could only endorse one stressor of each type per day. The daily diary interview stem questions were from the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE) (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). For the purpose of the current study, reactivity to two types of daily social stressors (argument tensions and avoided arguments) were examined.

Measures

Argument tensions

For eight consecutive evenings, participants were asked, “Did you have an argument or disagreement with anyone since (this time/we spoke) yesterday?” Participants who answered affirmatively were then asked a series of probe questions, including with whom the argument tension occurred.

Avoided arguments

Avoided arguments were defined as opportunities to engage in an argument that are passed in order to avoid a disagreement. For eight consecutive evenings, participants were asked, “Since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, did anything happen that you COULD have argued about but you decided to LET PASS in order to AVOID a disagreement?” If participants answered affirmatively to the stem question, they were asked probe questions similar to those for the argument tensions.

Total number of daily stressors

A count of the total number of daily stressors was obtained by computing the number of stressors reported each day and then aggregating across the eight days. A maximum of seven different types of stressors (as described above) could be endorsed each day. In the present study, the total number of daily stressors experienced across the week was used as a covariate in the models.

Daily negative affect

Daily negative affect was assessed using the Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998), which has been validated in diverse populations and measures current, general emotional distress. For more psychometric information on the scale, see Kessler et al. (2002). Every evening, participants used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time) to report how often they had experienced each of the following ten emotions during the past 24 hours: depressed, so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, worthless, hopeless, nervous, so nervous that nothing could calm you down, restless or fidgety, so restless that you could not sit still, that everything was an effort, and tired for no good reason.

Analyses

Hypotheses were tested with multi-level models using SAS PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, 1997). Multi-level modeling makes it possible to examine both between- and within-person variability through a two-level hierarchical model, where Level 1 represents within-person variability and Level 2 represents between-person variability (Raudenbusch & Bryk, 2002). Using this technique, we can determine how within-person processes, such as experiencing an interpersonal stressor, are influenced by between-subject factors, such as age. A full description of the statistical methodology of multi-level modeling can be found in Raudenbusch and Bryk (2002); for its application to daily diary paradigms, refer to Vansteelandt, Van Mechelen, and Nezlek (2005).

Analyses for the current study were based on the following composite model:

In this model, negative affect for person i on day t is a function of whether an interpersonal stressor was encountered on day t (b1), the age of the participant (b2), the interaction between age and exposure to interpersonal stressors (b3), and random intra-individual variation (ci). Two models were run; the first with argument occurrence as the interpersonal stressor and the second with argument avoidance as the interpersonal stressor.

Reactivity to daily stressors

Affective reactivity does not refer to well-being per se, but instead refers to the difference in levels of negative affect on days when a stressor occurs compared to days when no stressor occurs (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995). This change in level of negative affect represents the degree to which a stressor exerts an influence on an individual's daily affective well-being (Almeida, 2005; Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995). A significant association between the occurrence of a stressor and negative affect (i.e., slope change in negative affect resulting from the presence of a stressor), then, indicates affective reactivity.

Results

Participants reported experiencing at least one stressor of any type on 37.8% of interview days, and multiple stressors on 11.2 % of interview days. Interpersonal tensions accounted for approximately 45% of these stressors. Being in a situation where people actively avoided an argument was reported more often than was being in a situation where they actually had an argument or disagreement: whereas participants reported being in a situation where they chose to avoid an argument on 14.4% of interview days, they reported having an argument or disagreement on only 9.3% of interview days.

We examined with whom people avoided or had an argument for descriptive purposes. A total of 763 people, or 74% of the sample, reported experiencing either an argument or an avoided argument at least once during the course of the week. Of the 1,708 reported avoided arguments and argument tensions (1,038 avoided arguments; 670 arguments) we were able to code 1,293 incidents (774 avoided arguments; 519 arguments). For the purposes of these descriptive analyses, the types of social partners were divided into five groups: spouse, other family members, friends, volunteer/work associates and people not fitting into any of the aforementioned categories (e.g., store clerks). Table 1 provides a summary of these analyses.

Table 1.

Percent of Stressor Experiences across All Codeable Arguments and Avoided Arguments

| Social Partner Involved | Arguments n = 519 | Avoided Arguments n = 774 |

|---|---|---|

| Spouse/Romantic Partner | 35.5% | 28.9% |

| Other Family Members | 31.2% | 25.9% |

| Friends | 5.2% | 6.1% |

| Volunteer/Work Associates | 22.2% | 30.4% |

| Other | 6.0% | 8.8% |

To explore whether there were age differences in arguments or avoided arguments for specific types of social partners, we conducted additional analyses after dividing participants into three age groups: younger (25 to 39 years-old) middle-aged (40 to 59 years-old), and older adults (60 to 74 years-old). Across age groups, argument avoidance differed according to social partner type, χ2 (8, N =777) = 28.56, p < .001), as did argument occurrence (χ2 (8, N =511) = 34.74, p < .001; see Table 2). Older adults reported a greater percentage of their arguments with their spouses and a lower percentage with other family members. In contrast, younger and middle-aged adults reported a greater percentage of both types of stressors with their volunteer/work associates.

Table 2.

Percent of arguments and avoided arguments reported across age groups

| Younger | Middle-Aged | Older | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arguments | |||

| Spouse/Romantic Partner | 34.8 | 27.7 | 62.5 |

| Other Family Members | 32.4 | 33.6 | 15.3 |

| Friends | 4.4 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| Volunteer/Work Associates | 24.5 | 26.4 | 11.1 |

| Other | 3.9 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

| Avoided Arguments | |||

| Spouse/Romantic Partner | 33.3 | 23.4 | 34.5 |

| Other Family Members | 23.1 | 29.5 | 22.8 |

| Friends | 6.1 | 5.4 | 8.3 |

| Volunteer/Work Associates | 31.8 | 33.4 | 19.3 |

| Other | 5.7 | 8.4 | 15.2 |

Older age was related to both fewer arguments, r = −.14, p < .001, and fewer avoided arguments, r = −.10, p < .001. Considering all types of stressors together, older adults also reported fewer stressors of any type across the week than did younger adults, r = −.20, p <.001. As a result of this base rate difference in number of stressors, any age-related differences in affective reactivity found in these analyses could be a function of stressor exposure. Younger adults may, for example, report heightened reactivity to interpersonal tensions simply because they encountered more stressors overall. To control for this potential confound, total number of stressors was treated as a covariate in all analyses.

Reactivity to daily stressors on argument-avoidance days

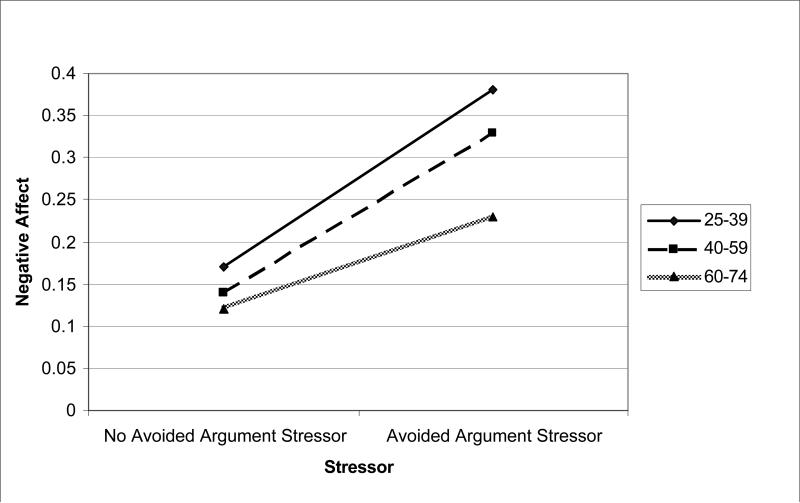

We hypothesized that on days arguments were avoided, older adults would experience less affective reactivity than would younger adults. To test this hypothesis, we used negative affect as the dependent variable in a multi-level model. Age (centered and continuous) and the avoidance of an argument (0 or 1) were the independent variables; gender, education, and total number of stressors were the covariates; and age by argument avoidance was entered as the interaction term. Table 3 presents the results of the model. The presence of an avoided argument was related to negative affect, indicating affective reactivity, such that people reported greater negative affect on days when they avoided an argument compared to days when no such tension occurred, F(1, 641) = 91.2, p < .001. In support of the hypothesis, the interaction between age and argument avoidance was significant, F(1,6138) =3.9, p < .05. Findings indicate that older age is related to lower levels of affective reactivity to an avoided argument. Figure 1 shows this interaction, with age divided into groups for descriptive purposes.

Table 3.

Age, Argument Avoidance, and Affect Reactivity

| Daily Negative Affect | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | b | SE b |

| Intercept | .367*** | .031 |

| Age | −.003** | .001 |

| Argument Avoidance | −.107*** | .011 |

| Total number of stressors | .030*** | .003 |

| Education | −.028*** | .004 |

| Gender | −.012 | .017 |

| Age × Argument Avoidance | .002* | .001 |

| Deviance | ||

| AIC | 2315.6 | |

| BIC | 2364.9 | |

n = 1,028

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

Age differences in affective reactivity in response to an avoided argument stressor.

Note. For descriptive purposes, age was grouped into three categories, reflecting younger, middle-aged and older adults.

Reactivity to daily stressors on argument days

We predicted that age would be beneficial on days arguments were avoided, but this difference would be attenuated for reactivity to an argument that had occurred. Variable entry was similar to the model above; in this model, however, we included argument occurrence as the independent variable instead of argument avoidance. Table 4 includes the results of this model. Once again, results show that the presence of an argument was significant and indicate that the experience of an argument increased people's negative affect levels, F(1, 430) = 60.3, p < .001. In addition, age offered no protective benefit for reactivity when arguments occurred: older adults were just as reactive as were younger adults F(1, 6140) = .2, n.s.

Table 4.

Age, Argument Occurrence, and Affect Reactivity

| Daily Negative Affect | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | b | SE b |

| Intercept | .396*** | .033 |

| Age | −.001 | .001 |

| Argument Occurrence | −.125*** | .016 |

| Total number of stressors | .032*** | .003 |

| Education | −.030*** | .004 |

| Gender | −.019 | .018 |

| Age × Argument Occurrence | .001 | .001 |

| Deviance | ||

| AIC | 2210.9 | |

| BIC | 2260.2 | |

n = 1,028; *p < .05 **p < .01

p < .001

Does the experience of affect reactivity vary within age group?

The above analyses revealed age differences in reactivity to different types of interpersonal stressors. We found no age differences in stressor reactivity on days people reported having an argument, but age differences in reactivity were present for avoided arguments (i.e., older adults reported less reactivity relative to younger adults to experienced arguments). Our hypotheses were confirmed, but we were interested in how these two experiences may vary within age groups to provide a better understanding of the meaning of these interaction effects. Findings suggest that older adults experience greater affective reactivity to an actual argument versus an avoided argument, but that younger adults experience similar affective reactivity in both situations. Before drawing any conclusions, however, we wanted to confirm these differences by comparing reactivity to these two types of social stressors across people of differing ages. We therefore compared correlation coefficients for stressor reactivity for these two experiences within three different age groups: young adults, ranging from 25 to 39; middle-aged adults, ranging from 40 to 59, and older adults, ranging from 60 to 74.

For each age group, individual multi-level models were run, with negative affect as the dependent variable and argument tensions, avoided arguments, number of stressors, gender and education as simultaneous independent variables. Beta estimates for arguments and avoided arguments were then compared. Results indicated that beta coefficients for affective reactivity to an argument versus an avoided argument were not significantly different from one another for younger, t(1873) = .69, β = .03, n.s, or middle-aged adults, t(2843) = −.73, β = −.020, n.s. These findings indicate that younger and middle-aged adults reacted similarly to both types of social tensions. Among older adults, however, reactions to these two situations were significantly different from one another, t(1431) = 2.54, β = .12, p < .05.

Results suggest that although arguments and avoided arguments incurred the same level of affective reactivity in younger and middle-aged adults, older adults reacted more strongly to an actual argument than to an avoided argument. To place the effects of these findings in perspective, our results indicate that for every 10 year increase in age, affective reactivity in response to argument avoidance decreases by 16%.

Discussion

Unpleasant social encounters, even those which people choose to ignore, create distress (Almeida, 2005), and all adults--regardless of age--experienced higher levels of distress on days when such experiences occurred compared to days free from stressors. The current study examined age differences in affective reactivity to two types of social stressors: one where people actively engaged in an argument and another where they decided to avoid a conflict. Based on prior research and current theory, we hypothesized that older age would be related to less affective reactivity in response to an avoided argument. We further predicted that age differences in affective reactivity would be attenuated in response to situations where people experience an argument. Results supported our hypotheses.

Avoiding negative social exchanges

Common emotion regulation advice often includes such platitudes as “let it go” or “just don't let it bother you.” The current results suggest that this strategy may be more successful – at least as far as affective reactivity is concerned – for older adults rather than younger adults. Research indicates that older adults report engaging in more passive strategies in response to interpersonal situations (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2007; Sorkin & Rook, 2006), and the current study suggests a possible reason why older adults favor these strategies: they experience less affective reactivity when they avoid confrontations. Socioemotional selectivity theory posits that older adults are more motivated by emotional goals, including the desire to maintain higher levels of affective well-being, than are younger adults (Carstensen et al., 1999). This theory is consistent with findings showing that when a tense social exchange ensues, older adults report the desire to preserve harmony as a main goal (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003). Another potential reason why older adults react to these situations with less distress is that they may have learned through experience that some arguments are not worth having, and they prefer harmony over discontentment (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003; Sorkin & Rook, 2006). Perhaps as a result of these preferences, older adults disengage from interpersonal tensions more often than do younger adults, who report arguing more often in response to a social conflict (Birditt et al., 2005).

Among younger and middle-aged adults, affective reactivity was similar regardless of whether the stressor was an avoided argument or an actual altercation. Perhaps one reason why older adults benefit from these strategies in terms of affective reactivity--whereas younger and middle-aged adults do not--is that passive strategies are more aligned with the motivational goals of older adults. Older adults may be less distressed because they have less to lose than younger adults when considering these social tensions and the future prospects that these problems or decisions may represent. In contrast, younger and middle-aged adults may focus on problem-solving and asserting their opinion (Birditt & Fingerman, 2005) because they have information-based goals that they need to accomplish, and their priorities reflect the need for active problem-solving strategies. In addition, the younger adults’ focus on asserting themselves and achieving specific goals may lead to rumination about the unresolved problem and greater affective reactivity as a result.

An alternative explanation for age differences in patterns of reactivity is that older adults may find themselves in situations that are less caustic and lend themselves to disengagement more easily than those situations faced by younger adults. For example, younger adults report more reluctance to engage in a direct confrontation with their elders than with their peers (Fingerman, Miller, & Charles, 2008). Disengagement, then, may be more mutual than unidimensional, with both parties desiring an amicable end to the conflict. This explanation, although not in direct opposition to our previous theoretical arguments, provides an interpretation based less on the skills of older adults and more about changing social context with age. This reasoning is consistent with that of other researchers who have discussed changing contexts with age as an explanation for why older adults report higher levels of well-being than younger adults (Lawton, Kleban, Rajagopal, & Dean, 1992).

Moreover, social situations are necessarily different with age: younger adults might experience power struggles with their parents, a situation that would be rare among older adults. Middle-aged adults may have power struggles with their parents, but these struggles would more often entail discussions about their parent's care rather than their own independence. And, disagreements with spouses occurred more often among older adults in the sample, perhaps because older couples spent more time together or perhaps are more dependent on one another for instrumental assistance. Although we examined age differences in reactions to different types of social tensions, we must bear in mind age differences according to social partner type and the context of these interactions. Future research should examine not only the age of the conflict partner, but also the participant's relationship with the conflict partner, including his or her levels of satisfaction, security, or dependence in the relationship. This line of research may clarify potential intergenerational dynamics, such as power struggles with social partners and their role in predicting affective reactivity to interpersonal tensions. Future research should also examine age differences in the frequency with which people are able to avoid even the prospect of a potential argument (situation selection) as opposed to the situation modification (disengaging from a negative situation) that was addressed in this study. The current study assessed stressors, and did not ascertain the frequency with which people used strategies that allowed them to avoid stressors completely.

Argument experience

In contrast to the age-related decrease in affective reactivity when opting out of an argument, older adults were just as emotionally reactive as were younger adults when they directly engaged in an argument. Although older adults report that they would rather avoid an argument if possible (e.g., Charles et al., 2001) and they reported fewer social arguments – both avoided and unavoided – than their younger counterparts, arguments did nonetheless arise. Moreover, the proportion of arguments avoided versus those that were not avoided among older adults was similar to the proportion observed among younger adults. Disagreements are arguably unavoidable and sometimes necessary when interacting with social partners. For example, disagreements over independence may be important for maintaining a sense of autonomy and control, issues important for people of all ages (Heckhausen, 1999). In these situations, older adults may engage in an argument at the expense of their emotional well-being. At times, having an argument provides short term discomfort, but long-term gains if conflicts are resolved and goals are achieved. Another possibility is that sometimes, no matter how hard one attempts to avoid the situation, an argument is inevitable. In this case, older adults may have engaged in proactive strategies to avoid these situations, but ultimately failed in their goal.

These findings appear to contrast with studies finding that older adults often show a positivity effect in their reactions to emotional events, such that they are less likely to remember negative events and more likely to remember positive ones (Mather & Carstensen, 2005). If older adults are adept at reappraisal and arguably have more experience employing cognitive-behavioral strategies of emotion regulation than their younger counterparts (Charles & Carstensen, 2007), why then are they not less reactive in response to arguments? If older adults have developed cognitive strategies of reappraisal that enable them to opt out of arguments and experience less reactivity as a result, why can they not they apply these same cognitive-behavioral strategies in response to an argument and subsequently experience lower levels of reactivity? We speculate that several reasons may contribute to why older adults do not show a positivity effect when recalling the negative affect they felt on the day they experienced an argument. First, older adults engage in strategies that allow them to focus away from the negative event and engage in strategies that limit their exposure to the negative event. These strategies may be responsible for the positivity effect. When people cannot or do not engage in these strategies, the positivity effect may disappear. This speculation is consistent with findings showing age-related reductions in affective reactivity to social stressors (the majority of which include an avoided argument rather than an actual argument) but not, for example, to work-related stressors or stressors about needed home repairs (Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007). These non-social stressors may be situations where a disengagement strategy cannot be easily employed, thus explaining the lack of age differences in affective reactivity. Future research will have to examine this possibility.

In addition, we speculate that the positivity effect may not be found in situations that entail regulating high levels of sustained physiological reactivity (see discussion in Charles & Piazza, in press). Negative interactions, even a short-term argument experienced in the laboratory setting, produce physiological arousal for adults of all ages (Levenson, et al., 1994; Smith, Gallo, Goble, Ngu, & Stark, 1998), but this physiological arousal may have higher potential costs for older, less flexible physiological systems. In situations of high arousal, for example recovery after physical exercise, older adults take longer to return to baseline than do younger adults (Deschenes, Carter, Matney, Potter, & Wilson, 2006). Both animal and human models further show prolonged physiological recovery with age (see review by Bjorntorp, 2002; Otte et al., 2005). These age-related decreases in physiological reactivity, then, may offset any cognitive-behavioral skills that older adults may be employing to regulate their emotions after experiencing physiological arousal. Future research will need to investigate whether the age-related positivity effect still remains in situations where people elicit sustained, high levels of physiological arousal in response to negative events. This future research will also have to examine the types and severity of stressors to which people are exposed, how physiological reactivity is related to these stressor characteristics, and what older and younger adults do in response to these stressors.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study examined reports of arguments, or the successful avoidance of them, in everyday life across people ranging from 25 to 74 years-old. We based the hypotheses and interpreted the findings using lifespan theory, but cohort effects could be responsible for these findings. For example, older cohorts may have been raised to inhibit emotional feelings and are therefore more successful at employing passive strategies than are younger cohorts. Longitudinal research spanning years and studying people across different age groups will need to test whether these findings are influenced, or even explained, by cohort effects. Gaining additional information about the nature of their social tensions will also illuminate factors responsible for age differences in affective reactivity. Laboratory situations that control for these factors may help to understand how internal processes, such as personal motivations as well as learned experience, play a role in negotiating negative social exchanges.

Conclusions

Older adults endorse leaving an argument or doing nothing as the best way to handle the situation and recommend these strategies to others (Charles et al, 2001), a stance shared by experts (Blanchard-Fields et al., 2007). To our knowledge, no study has directly tied more passive strategies to age differences in emotion-related outcomes. Passive strategies are not optimal in all situations, particularly when rapid actions and proactive strategies may allow people to avoid dangerous situations. Still, other situations call for these strategies (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). For example, opting to disengage from a friend who is upset and waiting until he or she has calmed down may be the better solution than engaging in a heated debate. Researchers refer to these strategies as passive, yet the actions of older adults may not be as “passive” as the term implies, but instead a selective emotion regulation strategy that benefits emotional well-being in later adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NIA AG019239 and NIA AG023845. We thank Karen Fingerman for her comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript, and Robert Stawski for his statistical advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/pag.

References

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The daily inventory of stressful events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Horn MC. Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Langfahl ES, Akiyama H. Relationships as outcomes and contexts. In: Lang FR, Fingerman KL, editors. Growing together: Personal relationships across the life span. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. pp. 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Age and gender differences in adults’ descriptions of emotional reactions to interpersonal problems. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58B:P237–P245. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.p237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Do we get better at picking our battles? Age group differences in descriptions of behavioral reactions to interpersonal tensions. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60B:P121–P128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, Almeida DM. Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: A daily diary study. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:330–340. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjöntorp P. Hypertension and the metabolic syndrome: Closely related central origin? International Congress Series. 2002;1241:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F. Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F, Mienaltowski A, Seay RB. Age differences in everyday problem-solving effectiveness: Older adults select more effective strategies for interpersonal problems. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62B:P61–P64. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.p61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Emotion regulation and aging. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL, McFall RM. Problem-solving in the nursing home environment: Age and experience differences in emotional reactions and responses. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2001;7:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR. Memories of social interactions: Age differences in emotional intensity. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:300–309. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR. Age Differences in Affective Well-Being: Context Matters. Social and Personality Compass. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes MR, Carter JA, Matney EN, Potter MB, Wilson MH. Aged men experience disturbances in recovery following submaximal exercise. Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Medical Sciences. 2006;61A:63–71. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Miller L, Charles S. Saving the best for last: How adults treat social partners of different ages. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:399–409. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J. Developmental regulation in adulthood: Age-normative and sociostructural constraints as adaptive challenges. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner KL, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Glaser R, Malarkey WB. Spousal support satisfaction as a modifier of physiological responses to marital conflict in younger and older couples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:233–254. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000028497.79129.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in midlife. In: Willis SL, Reid JD, editors. Life in the middle. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. pp. 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Rajagopal D, Dean J. Dimensions of affective experience in three age groups. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:171–184. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Fingerman KL. Positive and negative emotional feelings and behaviors in mother-daughter ties in late life. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:607–617. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson R, Carstensen LL, Gottman J. The influence of age and gender on affect, physiology, and their interrelations: A study of long-term marriages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:56–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrozek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62B:216–P225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C, Hart S, Neylan TC, Marmar CR, Yaffe K, Mohr DC. A meta-analysis of cortisol response to challenge in human aging: Importance of gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Emotional health and positive versus negative social exchanges: A daily diary analysis. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Gallo LC, Goble L, Ngu LQ, Stark KA. Agency, communion, and cardiovascular reactivity during marital interaction. Health Psychology. 1998;17:537–545. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin D, Rook KS. Dealing with negative social exchanged in later life: Coping responses, goals, and effectiveness. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:715–725. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story TN, Berg CA, Smith TW, Beveridge R, Henry NJM, Pearce G. Age, marital satisfaction, and optimism as predictors of positive sentiment override in middle-aged and older married couples. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:719–727. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Suls J, Affleck G. Personality and daily experience: The promise and the challenge. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B, Berg CA, Smith TS, Pearce G, Skinner M. Age-related differences in ambulatory blood pressure during daily stress: Evidence for greater blood pressure reactions in older individuals. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:231–239. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Uno D, Holt-Lunstad J, Flinders JB. Age-related differences in cardiovascular reactivity during acute psychological stress in men and women. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1999;54:339–346. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.6.p339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt K, Mechelen IV, Nezlek JB. The co-occurrence of emotions in daily life: A multilevel approach. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:325–335. [Google Scholar]