Abstract

The present experiments examined the role of within-compound associations in the interaction of the overshadowing procedure with conditioned stimulus (CS) duration, using a conditioned suppression procedure with rats. Experiment 1 found that, with elemental reinforced training, conditioned suppression to the target stimulus decreased as CS duration increased (i.e., the CS-duration effect), whereas with compound reinforced training (i.e., the overshadowing procedure) conditioned suppression to the target stimulus increased as CS duration increased. Subsequent experiments replicated these findings in sensory preconditioning and demonstrated that extinction of the overshadowing stimulus results in retrospective revaluation with short CSs and mediated extinction with long CSs. These results highlight the role of the duration of the stimulus in behavioral control. Moreover, these results illuminate one cause (the CS duration) of whether retrospective revaluation or mediated extinction will be observed.

Keywords: cue competition, retrospective revaluation, mediated extinction, overshadowing, CS duration, counteraction, within-compound association

When two cues are presented in compound and followed by a biologically significant outcome, competition between the cues for behavioral control is often observed. The simplest example of cue competition is the overshadowing effect: When two initially neutral cues are reinforced in compound, responding to either of the cues alone is often less than if they were separately trained. Theoretical explanations of cue competition phenomena like overshadowing have become one of the essential components of any viable model of learning; accordingly, many accounts of overshadowing have been proposed (e.g., Dickinson & Burke, 1996; Mackintosh, 1975; Miller & Matzel, 1988; Pearce & Hall, 1980; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Stout & Miller, 2007; Van Hamme & Wasserman, 1994; Wagner, 1981). Despite differences in accounts of exactly how overshadowing occurs, these theories uniformly predict the overshadowing effect. However, there is divergence in the predictions about what happens when the overshadowing stimulus is presented without reinforcement after training has occurred (i.e., posttraining extinction). There are three possible behavioral results of posttraining extinction. First, behavioral control by the target stimulus could increase as a result of extinguishing the overshadowing stimulus (e.g., Dickinson & Burke, 1996; Miller & Matzel, 1988; Stout & Miller, 2007; Van Hamme & Wasserman, 1994; i.e., retrospective revaluation). Second, behavioral control could decrease as a result of posttraining extinction of the overshadowing stimulus (e.g., Holland, 1990; i.e., mediated extinction). Third, extinction of the overshadowing stimulus could result in no change in behavioral control of the target stimulus (e.g., Mackintosh, 1975; Pearce & Hall, 1980; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Wagner, 1981).

Given these divergent predictions, there is a problem in that none of the aforementioned theories account for the divergent data: All of these consequences of extinguishing an overshadowing cue have been reported. None of the aforementioned theories anticipates which variables, if any, should influence the consequences of posttraining extinction of the more salient cue, perhaps because each of these theories only anticipates one of these outcomes. Previous research informs us that there are probably numerous variables that determine whether posttraining extinction will result in retrospective revaluation or mediated extinction. The main objective of the present series of experiments was to isolate one variable that determines these opposite outcomes. One example that sheds light on this puzzle is provided by Shevill and Hall (2004) who examined this issue and observed both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction in different experiments. A trend towards mediated extinction was seen after extinction of the more salient cue when they trained a compound of two cues simultaneously, and retrospective revaluation was seen when they used a compound in which the cues were presented serially. Thus, the nature of cue presentation may determine the outcome of posttraining extinction. Additionally, Liljeholm and Balleine (2006) have suggested that stimulus salience may influence whether or not retrospective revaluation will be observed, but their work did not address factors that produce mediated extinction.

We undertook a detailed literature review and after making cross-experiment and cross-publication comparisons concluded that a very strong association between a target conditioned stimulus (CS) and its associated stimulus can result in attenuated cue competition, and consequently weakened retrospective revaluation (e.g., Wheeler & Miller, 2008) or even mediated extinction (e.g., Holland, 1990) when the companion stimulus is extinguished. For example, Westbrook, Homewood, Horn, and Clarke (1983), using rats in a conditioned flavor aversion preparation, found that salient tastes overshadow weak odors with short duration CSs, but potentiate odors with long CS durations. That is, when an odor was accompanied by a taste during conditioning, there was a lower intake of liquid in the presence of the odor compared to a group that received odor accompanied by tasteless water during training. This phenomenon is commonly called potentiation (Clarke, Westbrook, & Irwin, 1979). Moreover, posttraining extinction of the salient taste after training with long duration stimuli decreased responding to the odor. In other words, they observed mediated extinction with long duration cues. A further instance of mediated extinction within a taste aversion preparation was reported by Schachtman, Kasprow, Meyer, Bourne, and Hart (1992). They administered two flavors followed by LiCl injection, and observed overshadowing. When the two flavors were presented serially, subsequent extinction of the overshadowing flavor had no effect on consumption of the overshadowed flavor. But when the two flavors were presented simultaneously, presumably resulting in a stronger within-compound association, subsequent extinction of the overshadowing flavor decreased consumption of the overshadowed flavor (i.e., mediated extinction).

Another example suggestive of the effect of the within-compound association was reported by Shevill and Hall (2004). They used a conditioned bar-press suppression preparation and found increased responding to the target cue as a result of extinguishing the overshadowing cue (i.e., retrospective revaluation) when the target and companion cues had been presented serially during training. However, decreased responding to the target cue occurred after extinguishing the overshadowing cue (i.e., mediated extinction) when the two cues had been presented simultaneously during training. Presumably, simultaneous presentations of the CSs results in a stronger within-compound association than do serial presentations because simultaneity provides superior contiguity (Rescorla, 1981). One could speculate that the moderate strength of the within-compound association between the cues created by the serial pairings (as opposed to the simultaneous pairings) was responsible for the occurrence of retrospective revaluation. Unfortunately, the lack of control groups for overshadowing precludes any conclusion about their observation of overshadowing. Additional evidence consistent with this speculation comes from Matzel, Schachtman, and Miller (1985) and Matzel, Schuster, and Miller (1987), who observed recovery from overshadowing as a result of extinguishing the overshadowing stimulus. The two series of experiments used identical parameters with the exception that Matzel et al. (1985) used fully simultaneous CSs, whereas Matzel et al. (1987) used a modified serial preparation in which the overshadowing stimulus was presented by itself during the first half of each CS interval and then in compound with the target stimulus during the last half. Although both experiments reported a significant overshadowing effect, stronger recovery from overshadowing (i.e., retrospective revaluation) was observed with the modified serial preparation (Matzel et al., 1987), which would be expected to have created a weaker within-compound association than would the simultaneous preparation.

Taken together, these experiments appear to indicate a nonmonotonic relationship between the strength of the within-compound association and cue competition (and/or retrospective revaluation). When there is a moderate within-compound association, there appears to be strong cue competition (i.e., overshadowing) and a propensity for retrospective revaluation achieved through extinction of the within-compound association. In contrast, with a very strong within-compound association, no cue competition or even potentiation is observed and extinction of the within-compound association results in mediated extinction. Of note, some researchers have found no effect of this posttraining manipulation perhaps because of there being a moderate, but not very strong within-compound association (e.g., Holland, 1999).

The primary objective of the present research was to investigate within-compound associations as a factor that might influence whether posttraining extinction of the companion stimulus after compound conditioning results in retrospective revaluation or mediated extinction. Thus, we sought to demonstrate retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction within one experiment by manipulating the within-compound association. In order to illuminate factors that yield retrospective revaluation or mediated extinction, the present experiments build on the work by Urushihara, Stout, and Miller (2004) and Urushihara and Miller (2007) who examined the conditioned stimulus (CS)-duration effect and used theoretical predictions made by the extended comparator hypothesis (ECH; Denniston, Savastano, & Miller, 2001). Urushihara and his colleagues observed the CS-duration effect with elemental cues (i.e., stronger stimulus control by shorter cues) and a reversal of the CS-duration effect with compounded cues. Similar to the above-mentioned study by Westbrook and colleagues (1983), less of a CS-duration effect was observed in the compound condition than the elemental condition, and less of an overshadowing effect was observed with long cues (25 s) than with short cues (5 s). This counterintuitive interaction of overshadowing and the CS duration effect led us to the main objective of these experiments: After obtaining overshadowing with short cues and no overshadowing with long cues, what will be the effect of extinguishing the overshadowing cue? Perhaps the strength of the within-compound association between the overshadowing and target cue determines the consequences of posttraining extinction. Cues of a short duration should presumably have a weaker within-compound association than longer cues because, the longer two cues are presented simultaneously, the stronger the association between them will be (Rescorla, 1981). This differing degree of within-compound association may reveal different patterns of responding after posttraining extinction. The second objective of the present series of studies was to replicate Urushihara and colleagues' findings and extend them to a compound five times longer (125 s). Though these experiments use predictions made by the ECH, which has a mechanism that anticipates both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction, a detailed description of the ECH and predictions has been deferred to the General Discussion so that we may begin by focusing on the empirical problem at hand.

Experiment 1

In Pavlovian situations, short cues ordinarily acquire greater behavioral control relative to cues of long duration. This phenomenon has been called the CS-duration effect (Schneiderman & Gormezano, 1964). This observation was the basis for our manipulation of the strength of the within-compound association. As previously mentioned, longer compound cues necessarily increase co-occurrence of the elements of the compound and this presumably increases the strength of the within-compound association between the elements. According to this analysis, short compound cues should not have such a strong within-compound association. In preparation for subsequent experiments, and to assess and extend the generality of the findings by Urushihara et al. (2004), in our first experiment we trained subjects with either a click alone (condition elemental) or a click plus a more salient tone (condition compound), stimuli that were 5, 25, or 125 s long. With short CSs (i.e., 5 s) we expected to observe the basic overshadowing effect. With 25 s long cues, we expected to see a reversal of the overshadowing deficit typically seen with 5 s long cues. This would replicate the findings of Urushihara et al. (2004). The immediate question was whether such an interaction between CS-duration and overshadowing treatment would also be seen with cues five times longer (i.e., 125 s). Therefore, the present experiment had six groups, as training was conducted either elementally or in compound in each of the three CS duration conditions. The design of Experiment 1 is shown in Table 1. Predictions are based on the ECH and explained in detail in the General Discussion.

Table 1. Design summary of Experiment 1.

| Group | Conditioning | Test | Pred ECH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elem 5 | X → US (8) | X | CR |

| Elem 25 | X → US (8) | X | Cr |

| Elem 125 | X → US (8) | X | cr |

| OV 5 | AX → US (8) | X | cr |

| OV 25 | AX → US (8) | X | Cr |

| OV 125 | AX → US (8) | X | CR |

Note: Elem = elemental acquisition control, OV = overshadowing treatment, 5, 25, and 125 = 5-s, 25-s, and 125-s CS duration, A (tone) = overshadowing stimulus, X (clicks) = target cue, US = footshock. Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of each trial type. Pred ECH = predictions of the extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001). CR, Cr, and cr denote strong, intermediate, and weak stimulus control, respectively.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were 36 female (170-210 g) and 36 male (220-320 g) Sprague-Dawley derived, experimentally naïve, young adult rats (N = 72), bred in our colony. Subjects were individually housed and maintained on a 16-hr light / 8-hr dark cycle with experimental sessions occurring roughly midway through the light portion. All subjects were handled for 30 s three times per week from weaning until the initiation of the study. Subjects had free access to food in the home cage. One week prior to initiation of the experiment, water availability was progressively reduced to 30 min per day, provided shortly after any scheduled treatment.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of six identical copies of each of two different types of experimental chambers. Chamber Rectangular (R) was a clear Plexiglas rectilinear chamber, measuring 23.0 × 8.5 × 12.5 cm (length × width × height). The floor was constructed of 0.48-cm diameter stainless-steel rods, spaced 1.5 cm apart center-to-center. The rods were connected by NE-2 neon bulbs that allowed a constant-current footshock to be delivered by means of a high voltage AC circuit in series with a 1.0-MΩ resistor. Each copy of Chamber R was housed in a separate light- and sound-attenuating environmental isolation chest, which was dimly illuminated by a 2-W incandescent bulb. The houselight was mounted on the ceiling of the environmental chest, approximately 30 cm from the center of the experimental chamber.

Chamber V-shaped (V) was a 25.5 cm long box in a vertical truncated-V shape (28 cm height, 21 cm wide at the top, 5.25 cm wide at the bottom). The floor and long sides were constructed of stainless steel sheets, the short sides were constructed from black Plexiglas, and the ceiling was constructed of clear Plexiglas. The floor of each chamber consisted of two parallel metal plates, each 2.0 cm wide, with a 1.25-cm gap between them. Each V-shaped chamber was housed in its own environmental isolation chest, which was dimly illuminated by a 7-W incandescent houselight mounted on an inside wall of the environmental chest, approximately 30 cm from the center of the experimental chamber. The light entering the animal chamber was primarily reflected from the white roof of the environmental chest. The light intensities in the two types of chambers were approximately equal, due to the differences in opaqueness of the walls in Chambers R and V.

Each chamber (R and V) could be equipped with a water-filled lick tube which extended 1 cm from the rear of a cylindrical niche, 4.5 cm in diameter, left-right centered in one short wall, with its axis perpendicular to the wall, and positioned with its center 4 cm above the floor of the R chamber and 4.5 cm above the floor in the V chamber. Each niche had a horizontal infrared photobeam traversing it parallel to the wall on which the niche was mounted, 1 cm in front of the lick tube. In order to drink from the tube, subjects had to insert their heads into the niche, thereby breaking the infrared photobeam. Thus, we could record when subjects had their heads in the niche with the water tube. Ordinarily, they did this only when they were drinking. Disruption of ongoing drinking by a test stimulus served as our dependent variable.

Each chamber (R and V) was also equipped with three 45-Ω speakers on the inside walls of the isolation chests that could deliver a complex tone (650 and 700 Hz) 10 dB (C-scale) above background (74 dB, produced mainly by a ventilation fan), a click train (10 Hz) 6 dB (C) above background, or a white noise stimulus 8 dB (C) above background. The clicks served as the target (X) and the tone served as the overshadowing cue (A). The white noise was used only in Experiments 3 and 4. A 1.0-mA, 0.5-s footshock, which served as the unconditioned stimulus (US), could be delivered through the chamber floors.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of six groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex, based on the duration of the CS (5, 25, or 125 s) and on whether they received training with one cue (Elemental [Elem]) or two cues (Overshadowing [OV]; see Table 1). Phase 1 was conducted in one (training) context (V or R) and all other treatments were conducted in the remaining (test) context in a counterbalanced manner within groups. This was done to minimize group-wise differential fear of the test context summating with fear of the CS at test. One might suspect that this change of context may result in AAB renewal; which is the observation of recovered conditioned responding to a stimulus that has been trained and extinguished in one context (A) and then tested in a different context (B). However, we know from previous research in our laboratory that AAB renewal is very weak and sometimes nonexistent (Laborda, Witnauer, & Miller, submitted).

Acclimation

On Day 1, pre-exposure to the test context was conducted. Subjects were exposed to the experimental chamber for a 45-min session. Water-filled lick tubes were available during this session.

Conditioning

Prior to this phase the lick tubes were removed from the training context. On Days 2-3, during daily 20-min sessions, subjects in the Elem condition received 4 X-US trials on each day which were terminated 4, 8, 12, and 18 min into each session. Subjects in the OV condition experienced 4 AX-US trials in each session, occurring at the same times as the elemental events. CSs A and X were always presented simultaneously. Cue duration was 5, 25, or 125 s, depending on the CS-duration condition. The footshock occurred during the last 0.5 s of the cues. Notably, there were only eight training trials. This low number was selected because overshadowing is known to wane with larger numbers of trials (Stout, Arcediano, Escobar, & Miller, 2003) and because prior research indicated that it was insufficient for the development of inhibition of delay which often emerges with long CSs given sufficient training (Rosas & Alonso, 1996).

Reacclimation

On Days 4 and 5, the lick tubes were reinserted, and subjects were allowed to drink during daily 45-min sessions in the test context. This treatment was intended to restabilize baseline levels of drinking. These sessions did not include any nominal stimulus presentations. Subjects taking more than 60 s to complete the first 5 cumulative seconds of drinking on Day 4 received an extra 30-min session on the same day.

Test

On Day 6, with the lick tubes present in the test context, all subjects were tested for suppression to CS X. This was accomplished by presenting X immediately upon completion of the first 5 cumulative seconds of licking (as measured by the total amount of time the infrared photobeam was disrupted). Thus, all subjects were drinking at the time of CS onset. Time to complete this initial 5 cumulative seconds of licking (pre-CS scores) and time to complete 5 additional seconds after the onset of the test CS (CS score) were recorded. Test sessions were 16 min in duration with a ceiling score of 15 min being imposed on the time to complete 5 cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the test CS.

Data analysis

In all experiments reported here, suppression data were transformed to log (base 10) scores to better approximate a normal distribution of scores within groups, thereby facilitating the use of parametric statistics. An alpha level of .05 (two-tailed) was adopted for all statistical tests. We report effect sizes calculated using the algorithm provided by Myers and Well (2003, p. 210). Following the convention of our laboratory, subjects that took more than 60 s to complete their first 5 cumulative seconds of licking (i.e., prior to CS onset), thereby exhibiting an unusual reluctance to drink in the test context, were eliminated from all analyses. No rat met this criterion in Experiment 1.

Results and Discussion

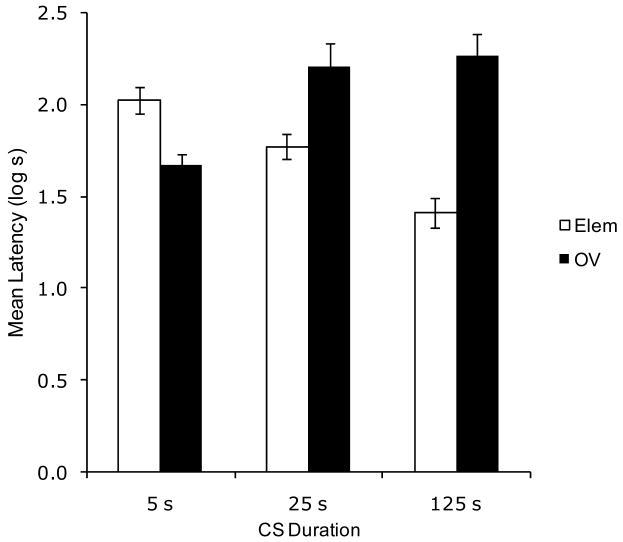

Figure 1 illustrates mean suppression to the target that was observed in Experiment 1. Greater suppression was observed in the Group Elem 5 than in Group OV 5, demonstrating basic overshadowing with 5-s cues. However, suppression was weaker in Group Elem 25 than in Group OV 25; indicating a reversal from the 5-s condition. This latter relationship was also observed in the 125-s condition with greater suppression in Group OV 125 than in Group Elem 125. Overall, these results show that as subjects in the Elem groups were exposed to longer CS durations, suppression diminished (i.e., a CS duration effect), but the reverse was seen in the OV groups (i.e., a counteraction of long CS duration by overshadowing treatment). The present results replicate those of Urushihara et al. (2004) and extend their generality to compounds of 125 s.

Figure 1.

Results of Experiment 1. Mean log latencies to complete the first five cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the target cue (X). Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text for details.

These observations are supported by the following analyses. The transformed data were initially analyzed by means of a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with type of training (Elem vs. OV) and CS duration (5 vs. 25 vs. 125 s) as factors. A 2 × 3 ANOVA conducted on pre-CS log-transformed latencies did not yield any main effects or interactions, all ps > .29. This indicates that there were no appreciable group differences in fear evoked by the test context. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the log-transformed latencies to resume drinking in the presence of the target CS. This analysis revealed a main effect of type of training, F(1, 66) = 15.47, MSE = .11, and an interaction between the two factors, F(2, 66) = 19.51, MSE = .11, Cohen's f = .72.

Planned comparisons using the overall error term of the latter ANOVA were conducted to assess the source of this interaction. A comparison between Groups Elem 5 and OV 5 revealed less suppression to the target CS when training was conducted in the presence of an overshadowing cue, F(1, 66) = 6.27, indicating a basic overshadowing effect. A similar comparison between Groups Elem 25 and OV 25 also revealed differences, F(1, 66) = 9.66. Moreover, a comparison between Groups Elem 125 and OV 125 demonstrated that these groups responded differently to the target CS, F(1, 66) = 38.56. Critically, the ordinal relationship in the groups trained with a 25- and 125-s CS was opposite to that in the groups trained with a 5-s CS. Thus, with short CSs overshadowing was observed, but with longer CSs a counteraction between CS duration and overshadowing occurred. A comparison between Groups Elem 5 and Elem 25 revealed a marginally significant difference, F(1, 66) = 3.37, p = .07, and a comparison between Groups Elem 5 and Elem 125 proved significant, F(1, 66) = 20.16. This reflects a decrease in suppression with longer elemental CSs, that is, a CS duration effect. A comparison between Groups OV 5 and OV 25 detected an increase in suppression when subjects were trained with a longer CS, F(1, 66) = 9.40. A final comparison between Groups OV 5 and OV 125 showed that the increase in suppression with longer CS durations was also observed in the 125 s condition, F(1, 66) = 17.84.

The results of Experiment 1 clearly demonstrate the basic overshadowing effect (in the 5-s condition), a CS-duration effect (in the elemental condition), and also that long CS-durations tend to counteract the overshadowing treatment. Specifically, when long cues were combined with the overshadowing treatment, suppression to the target CS was greater than with either deleterious treatment alone. These observations replicate the basic findings of Urushihara et al. (2004) and are in accord with the predictions of the ECH (Denniston et al., 2001). The expected strong suppression to the target cue when long CS duration and overshadowing treatments are combined was observed with CS durations of 25 and 125 s. It seems likely that, with CSs even longer than 125 s, suppression to the target stimulus in the OV condition would decrease due to poor CS-US contiguity. We conclude, therefore, that our longest CS (125 s) was sufficiently long to produce the counteraction effect, but not so long as to produce poor CS-US contiguity.

One might speculate that the present CS-duration effect observed with elemental training reflects inhibition of delay (Pavlov, 1927) rather than competition of the target with the context. However, this possibility is refuted by the absence of a CS-duration effect with compound training, given that the effects of inhibition of delay might also be expected to occur after this form of training.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 suggests that the result of training two cues in a compound depends on the duration of those cues. Short cues result in overshadowing and long cues result in no cue competition. Experiment 2 was designed to assess whether this factor is relevant to the discrepancy in the literature wherein posttraining extinction after overshadowing training sometimes results in mediated extinction, retrospective revaluation, or no change.

In this experiment we omitted the elemental control groups in order to focus on what happens during posttraining extinction after overshadowing training. The 25-s CS duration was also omitted in order to focus on the extremes of our CS durations and better capture a possible determinant of these opposite outcomes of posttraining extinction. Our control groups here received overshadowing treatment with 5s or 125s long CSs but no posttraining extinction. This allowed us to ascertain whether overshadowing occurred when the CS duration is short and whether cue competition did not develop when overshadowing treatment is conducted with long CSs. For each CS duration we included a group for which the overshadowing stimulus was extinguished after overshadowing training. If CS duration (and thus within-compound association) affects the outcome of posttraining extinction, a difference between the two groups should have resulted. Moreover, previous work by Urushihara and colleagues (2004; 2007) strongly suggests that the associative status of the training context is important to the observation of the present CS-duration and overshadowing interactive effects. Therefore, we included a group for each CS duration for which the training context was extinguished after overshadowing training. The predictions in Table 2 are based on the ECH and explained in detail in the General Discussion.

Table 2. Design summary of Experiment 2.

| Group | Conditioning | Extinction | Test | Pred ECH | Pred Biol Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NoExt 5 | AX → US (8) | Short Ctx (20 min) | X | cr | cr |

| NoExt 125 | AX → US (8) | Short Ctx (20 min) | X | CR | CR |

| ExtA+C 5 | AX → US (8) | A- (200) in long ctx (8 h) | X | CR | CR |

| ExtA+C 125 | AX → US (8) | A- (200) in long ctx (8 h) | X | CR | CR |

| ExtC 5 | AX → US (8) | Long Ctx (8 h) | X | cr | cr |

| ExtC 125 | AX → US (8) | Long Ctx (8 h) | X | cr | CR |

Note: NoExt = No extinction treatment, ExtA+C = Extinction of A and the context, ExtC = Extinction of the context, 5 and 125 = 5-s and 125-s CS duration, A (tone) = overshadowing stimulus, X (clicks) = target cue, US = footshock. Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of each trial type or duration of context exposure. Pred ECH = predictions of the extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001). Pred Biol Significance = predictions based on the principle of biological significance (Miller & Matute, 1996). CR and cr denote strong and weak stimulus control, respectively.

There is one potential factor that may militate against our observing significant changes in responding to the target after posttraining manipulations. Posttraining extinction of the context or the overshadowing cue in the long CS condition could result in a decrease in behavioral control by the target stimulus (i.e., mediated extinction). The problem is that past research in our laboratory has consistently shown that it is very difficult to decrease conditioned responding to a stimulus that is “biologically significant” by indirect means that exclude presentations of the target (i.e., extinction) or devaluation of the US (e.g., Miller & Matute, 1996). A biologically significant stimulus is one that controls behavior, either inherently (e.g., shock) or through associations with another biologically significant stimulus. The reasons why it is hard to decrease responding to a biologically significant stimulus through indirect manipulations are not very clear, but it has been speculated that animals adopt a conservative strategy regarding stimuli in their environment that are biologically relevant (Denniston, Miller, & Matute, 1996; Miller & Matute, 1996). One of the most straightforward examples of the principle of biological significance is backward blocking, which has not been demonstrated in non-human animals in conventional first-order conditioning. However, it is not yet clear whether this lack of backward blocking observations results from the blocking cue already being at asymptotic levels or because of biological significance. That is, it may be possible that backward blocking is not readily observed because during the first phase both cues reach asymptotic levels, in which case during the second phase the blocking cue would not have much associative strength to gain. The present experiment presents an opportunity to test this alternative to the biological significance account, in that with our procedure the posttraining manipulation involves nonreinforced trials rather than reinforced trials. Therefore, if backward blocking is not observed in first-order conditioning due to the ineffectiveness of further pairings to decrease responding, then a decrease in responding should readily be observed here. However, if the difficulty in observing backward blocking in first-order conditioning results from the principle of biological significance (as described by Miller and colleagues), then no decrease in responding to the target should be seen here either. In the current experiment, because the target CS X in the 125-s CS condition will have gained initial control of behavior (i.e., biological significance) as a result of its being paired with the US in conjunction with its long duration, the principle of biological significance predicts that extinction of the overshadowing cue should not result in a decrease in responding.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 36 female (162-233 g) and 36 male (181-318 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats (N = 72), bred in our colony. The animals were housed and maintained as in Experiment 1. The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those used in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of six groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex, defined by the duration of the CS (5 or 125 s) and whether they received mere handling (5 min of context exposure on extinction days [NoExt]), context extinction (120 min of context exposure on extinction days [ExtC]), or extinction of the overshadowing cue (A) and the context ([ExtA+C] see Table 2). Phase 1 and Phase 2 were conducted in one [training] context (V or R) and all other treatments in the remaining [test] context in a counterbalanced manner within groups.

Acclimation

On Day 1, animals were acclimated to the test context as in Experiment 1.

Phase 1 (Conditioning)

Prior to Phase 1 the lick tubes were removed from the training chambers. On Days 2-3, during daily 20-min sessions, all groups received 4 AX-US trials on each day which were terminated 4, 8, 12, and 18 min into each session. The footshock occurred during the last 0.5 s of the cues. Cue duration was 5 or 125 s. This matches the treatments of Groups OV 5 and OV 125 in Experiment 1.

Phase 2 (Extinction treatment)

Lick tubes were not present in the training chambers during Phase 2. On Days 4-7, subjects were treated in one of the three conditions to which they were assigned orthogonal to Conditions 5 and 125. Subjects in Condition ExtC experienced daily 120-min sessions in the training context with no nominal stimulus presentations. Subjects in Condition ExtA+C experienced daily 120-min sessions in the training context and during each session received 50 nonreinforced presentations of the overshadowing stimulus A of the same duration as in training. Thus, these subjects experienced extinction of both A and the context. It would have been preferable, in terms of theoretical analysis, to have extinguished only A without the context, but presentations of A outside the context may have encouraged renewal effects (e.g., Lipatova, Vadillo, Wheeler, & Miller, 2006). The first trial for the 5-s condition started 45 s into the session, and the mean intertrial interval (from CS termination to CS onset) was 140 s (range: 70 – 210 s). The last CS terminated 45 s before the end of the session. The first trial for the 125-s condition started 34 s into the session, and the mean intertrial interval was 18 s (range: 10 – 26 s). The last CS terminated 34 s before the end of the session. Subjects in Condition NoExt experienced 5 min of exposure to the training context on each day with no nominal stimulus presentations. These groups were intended to control for retention interval and handling effects.

Reacclimation and Testing

On Days 8 and 9, subjects were each given daily 45-min sessions of exposure to the lick tubes in the test context. On Day 10, lick suppression in response to the clicks (X) was measured in the test context for all subjects using the procedure described in Experiment 1.

Results and Discussion

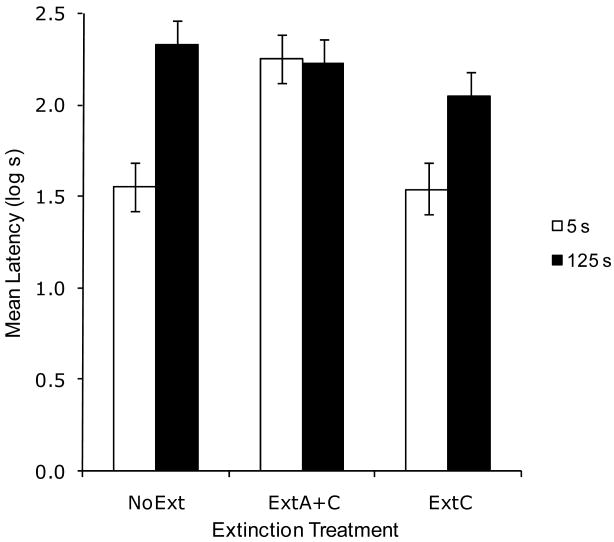

Half of the subjects from each group in this experiment were lost due to an experimenter error and an additional one from Group ExtC 5 was lost at test due to an equipment malfunction. Despite the loss of half of the subjects from each group, the remaining animals remained counterbalanced in the same manner as stated previously. Based on the remaining subjects (see Figure 2), greater suppression was observed in Group NoExt 125 than in Group NoExt 5, demonstrating strong behavioral control when overshadowing treatment is conducted with CSs of long CS duration. This replicates the central result of Experiment 1. Extinction of A and the context appeared to enhance suppression to X in Group ExtA+C 5, which is consistent with prior reports of attenuated overshadowing as a result of posttraining extinction of the overshadowing cue (e.g., Kauffman & Bolles, 1981; Matzel et al., 1985; Matzel et al., 1987). Consistent with the notion that stimuli with acquired biological significance are resistant to posttraining manipulation of its associates, Group ExtA+C 125 exhibited strong conditioned suppression. Extinction of the context alone had no effect in the short (5 s) CS condition. Suppression did not appear significantly different in Groups ExtA+C 125 and ExtC 125 compared to Group NoExt 125. This is also consistent with prior reports of difficulty in reducing behavioral control to a biologically significant CS through means other than presenting the CS or devaluing the US (e.g., Miller & Matute, 1996). The following statistics confirmed these impressions.

Figure 2.

Results of Experiment 2. Mean log latencies to complete the first five cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the target cue (X). All subjects were trained with the AX compound. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text for details.

A 2 × 3 ANOVA with CS duration (5 vs. 125 s) and extinction (NoExt vs. ExtA+C vs. ExtC) as main factors conducted on pre-CS log latencies did not yield any main effects or interactions, all ps >.25. This indicates that there were no appreciable differences among groups in fear evoked by the test context. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the log-transformed latencies to resume drinking in the presence of the target CS. This analysis revealed a main effect of extinction, F(2, 29) = 6.17, MSE = .097, a main effect of CS duration, F(1, 29) = 15.98, MSE = .097, and an interaction between the two factors, F(2, 29) = 4.91, MSE = .097, Cohen's f = .47.

Planned comparisons using the overall error term of the latter ANOVA were conducted to assess the source of the interaction. A comparison between the groups in the NoExt condition revealed less responding to the target CS in Group NoExt 5 than in Group NoExt 125, F(1, 29) = 18.39, consistent with the findings of Experiment 1. A comparison between Groups NoExt 5 and ExtA+C 5 showed a robust recovery from the overshadowing effect (i.e., retrospective revaluation), F(1, 29) = 14.76. A comparison between Groups NoExt 125 and ExtA+C 125 showed no significant effect of the posttraining manipulation, F(1, 29) = 0.26, p = 0.61, possibly because the long target CS already exerted strong behavioral control before the extinction treatments (i.e., was biologically significant), and posttraining extinction of a companion stimulus in this situation is rarely effective in reducing behavioral control (Miller & Matute, 1996). This lack of significant reduction in conditioned suppression was not due merely to a lack of statistical power as we would need 45 subjects in each group in order to demonstrate a reliable difference (the aforementioned power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3). A comparison between Groups NoExt 125 and ExtC 125 also failed to reveal a significant effect of extinguishing the context; Figure 2 makes clear that this was not due to insufficient statistical power. That is, overshadowing of X by A did not emerge after context extinction, F(1, 29) = 2.41, p = 0.13. This observation is also consistent with the principle of biological significance (Miller & Matute, 1996). In summary, in the 125-s condition, neither extinction of the training context nor extinction of A and the context appreciably influenced conditioned suppression to the target cue, perhaps due to the principle of biological significance. However, in the 5-s condition a retrospective revaluation effect (i.e., recovery from overshadowing) was observed after extinction of the overshadowing cue.

The results of this experiment demonstrate that the retrospective revaluation effect cannot be readily reversed by manipulations in which the target CS is not presented when the reversal would be manifested as a decrease in behavioral control by the target. This is consistent with data from prior experiments conducted in our laboratory (e.g., Denniston, Miller, & Matute, 1996; Miller & Matute, 1996; Oberling, Bristol, Matute, & Miller, 2000) suggesting that, when a stimulus has inherent or acquired biological significance, it is difficult to reduce responding to that stimulus through posttraining manipulation of a comparator stimulus. This principle of biological significance seems also to apply to the present experiment and apparently prevented us from testing the effect of CS duration on the outcome of posttraining extinction.

Experiment 3

Embedding these treatments within what is conventionally the first phase of a sensory preconditioning procedure is one way to examine the effect of posttraining extinction without the target CS having a potential to control behavior at the time of the extinction treatment. In a sensory preconditioning procedure (Brodgen, 1939), the target cue (and the overshadowing cue in the case of compound conditioning) are paired during training with an innocuous surrogate outcome (S), and in a subsequent phase S is paired with a biologically significant US, such as footshock (S-US). This procedure allows posttraining manipulations to be conducted before the target (X) has acquired biological significance (i.e., comes to control behavior) and becomes immune to these posttraining manipulations. Therefore, Experiment 3 was designed to replicate Experiment 1 but with the critical treatment (conditioning) embedded within a sensory preconditioning preparation. It was necessary to replicate the findings of Experiment 1 to ascertain that the basic effects of overshadowing and CS duration as well as their interaction could still be observed in this sensory preconditioning preparation. Moreover, a replication in sensory preconditioning would add generality to these findings. We used a similar design and parameters to those used in Experiment 1. A 5-s white noise served as the surrogate US (S) during the initial phase of sensory preconditioning. The white noise was then paired with shock in the second phase of the study (see Table 3).

Table 3. Design summary of Experiment 3.

| Group | Conditioning | Surrogate Training | Test | Pred ECH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elem 5 | X → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | CR |

| Elem 25 | X → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | Cr |

| Elem 125 | X → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | cr |

| OV 5 | AX → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | cr |

| OV 25 | AX → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | Cr |

| OV 125 | AX → S (8) | S → US (4) | X | CR |

Note: Elem = elemental acquisition control, OV = overshadowing treatment, 5, 25, and 125 = 5-s, 25-s, and 125-s CS duration, A (tone) = overshadowing stimulus, X (clicks) = target cue, S (white noise) = surrogate outcome, US = footshock. Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of each trial type. Pred ECH = predictions of the extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001). CR, Cr, and cr denote strong, intermediate, and weak stimulus control, respectively.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 36 female (170-248 g) and 36 male (238-327 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats (N = 72), bred in our colony. The animals were housed and maintained as in Experiments 1 and 2. The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those used in the prior experiments, except for the addition of the white noise, 8 dB (C) above background, which served as S, the outcome.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of six groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex, based on the duration of the CS (5, 25, or 125 s) and on whether they received training with one cue (Elem) or two cues (OV) during training. Phase 1 was conducted in one [training] context (V or R) and all other treatments in the remaining [test] context in a counterbalanced manner within groups.

Acclimation

The 45-min acclimation session on Day 1 was identical to that of the previous experiments.

Phase 1 (Conditioning)

Prior to Phase 1 the lick tubes were removed from the training chambers. On Days 2-3, during daily 20-min sessions, subjects in the Elemental condition received 4 X-S trials on each day, which were terminated 5, 10, 14, and 18 min into each session. Subjects in the OV condition experienced 4 AX-S trials on each day, occurring at the same times as the Elem condition. In both conditions the surrogate outcome (S) was presented immediately upon termination of the CS for 5 s. Cue duration was 5, 25, or 125 s.

Phase 2 (Surrogate training)

Lick tubes were not present in the test context during Phase 2. On Day 4, all subjects received four S-US pairings in one 60-min session, which occurred at 12, 22, 36, and 48 min into the session. The US was presented in the last 0.5 s of the presentation of S.

Reacclimation and Testing

On Days 5 and 6, subjects were each given a daily 45-min session of exposure to the lick tubes in the test context. On Day 7, lick suppression in response to the clicks (X) was measured in the test context using the same procedure as the previous experiments.

Results and Discussion

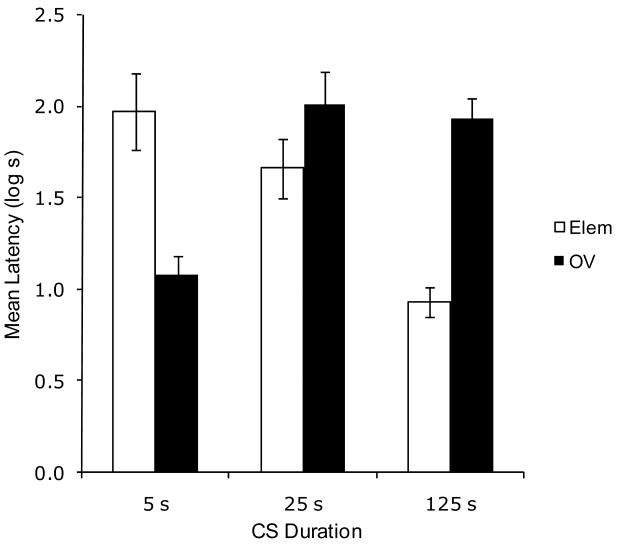

Experiment 3 replicated Experiment 1, but in a sensory preconditioning procedure. Greater conditioned suppression was observed in Group Elem 5 than Group OV 5, thereby demonstrating the basic overshadowing effect (See Figure 3). In the 25-s CS condition, this relationship was reversed between the Elem and OV groups; that is, there was greater suppression in Group OV 25 than in Group Elem 25. This tendency was larger in the 125-s condition, with greater suppression in Group OV 125 than Group Elem 125. In other words, as subjects in the Elem condition were exposed to longer CS durations, suppression diminished, and the reverse was found in the OV condition. These observations were supported by the following analyses.

Figure 3.

Results of Experiment 3. Mean log latencies to complete the first five cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the target cue (X). Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text for details.

A 2 × 3 ANOVA with training (Elem vs. OV) and CS duration (5 vs. 25 vs. 125 s) as main factors conducted on pre-CS log latencies did not yield any main effects or interactions, all ps > .31. This means that there were no appreciable differences among groups in fear evoked by the testing context. Three rats (one each from Groups Elem 5, Elem 25, and OV 125) took longer than 60 seconds to complete their first 5 seconds of licking and thus were excluded from all of the analyses. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the log-transformed latencies to resume drinking in the presence of the target CS. This analysis revealed a main effect of CS duration, F(2, 63) = 4.16, MSE = .25, and an interaction between the two factors, F(2, 63) = 20.92, MSE = .28, Cohen's f = .76.

Planned comparisons using the overall error term of the latter ANOVA were conducted to assess the source of the interaction. A comparison between Groups Elem 5 and OV 5 revealed less suppression to the target CS when training was conducted in the presence of an overshadowing cue, F(1, 63) = 18.01, thereby documenting overshadowing with 5-s CSs. However, a comparison between Groups Elem 125 and OV 125 found greater suppression to X in the OV condition, F(1, 63) = 22.66. Comparisons between groups trained with a single element revealed a difference between Groups Elem 5 and Elem 125, F(1, 63) = 24.53. This reflects a decrease in responding with longer CSs which is consistent with longer CSs accruing less behavioral control (i.e., the CS duration effect). Of note, the ordinal relationship between the groups trained with a 25- and 125-s CS was opposite to that in groups trained with a 5-s CS. Thus, with a short CS overshadowing was observed, but with longer CSs the CS duration and overshadowing effects appear to have cancelled each other.

This experiment replicated the findings of Experiment 1 but now within a sensory preconditioning procedure; that is, we observed a decrease in suppression with longer CSs when elemental training was administered and an increase in suppression with longer CSs when compound (overshadowing) training was administered.

Experiment 4

Experiment 4 was designed to test the same issues as Experiment 2, but within a sensory preconditioning preparation. It was necessary to test the manipulations of Experiment 2 embedded within a sensory preconditioning procedure in order to prevent the biological significance acquired by CS X in Phase 1 of Experiment 1 from obstructing changes in the response potential of the target cue during extinction treatment. By doing so, we expected to be able to properly assess the associative consequences of the different posttraining extinction treatments. We also wanted to determine if the absence of mediated extinction observed in Experiment 2 was (in part) due to biological significance. Predictions found in Table 4 and are based on the ECH, and will be explained in detail in the General Discussion.

Table 4. Design summary of Experiment 4.

| Group | Conditioning | Extinction | Surrogate Training | Test | Pred ECH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NoExt 5 | AX → S (8) | Short Ctx (20 min) | S → US (4) | X | cr |

| NoExt 125 | AX → S (8) | Short Ctx (20 min) | S → US (4) | X | CR |

| ExtA+C 5 | AX → S (8) | A- (200) in long ctx (8 h) | S → US (4) | X | CR |

| ExtA+C 125 | AX → S (8) | A- (200) in long ctx (8 h) | S → US (4) | X | CR |

| ExtC 5 | AX → S (8) | Long Ctx (8 h) | S → US (4) | X | cr |

| ExtC 125 | AX → S (8) | Long Ctx (8 h) | S → US (4) | X | cr |

Note: NoExt = No extinction treatment, ExtA+C = Extinction of A and the context, ExtC = Extinction of the context, 5 and 125 = 5-s and 125-s CS duration, A (tone) = overshadowing stimulus, X (clicks) = target cue, S (white noise) = surrogate outcome, US = footshock. Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of each trial type or duration of context exposure. Pred ECH = predictions of the extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001). CR and cr denote strong and weak stimulus control, respectively.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were 36 female (149-227 g) and 36 male (220-315 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats (N = 72), bred in our colony. The animals were housed and maintained as in the prior experiments. The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those used in Experiment 3.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of six groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex, based on the duration of the CS (5 or 125 s) and on whether they received handling (5 min of context exposure on extinction days), context extinction (120 min of context exposure on extinction days), or extinction of the overshadowing cue (A) and the context (see Table 4).

Acclimation

The 45-min acclimation session on Day 1 was identical to that of the prior experiments.

Phase 1 (Conditioning)

Prior to Phase 1 the lick tubes were removed from the training chambers. On Days 2-3, during daily 20-min sessions, all groups received 4 AX-S trials on each day which were terminated 5, 10, 14, and 18 min into each session. The surrogate outcome occurred immediately upon termination of the CS for 5 s. Cue duration was 5 s or 125 s. This matches the treatments of Groups OV 5 and OV 125 in Experiment 3.

Phase 2 (Extinction treatment)

On Days 4-7, subjects received extinction of the training context (ExtC), A and the context (ExtA+C), or no extinction (NoExt) exactly as in Phase 2 in Experiment 2.

Phase 3 (Surrogate training)

On Day 8, all subjects received 4 S-US pairings in the test context, which occurred in the same manner as in Phase 2 of Experiment 3.

Reacclimation and Test

On Days 9 and 10, subjects were each given daily 45-min sessions of exposure to the lick tubes in the test context. On Day 11, lick suppression in response to the clicks (X) was measured in the test context using the same procedure as the prior experiments.

Results and Discussion

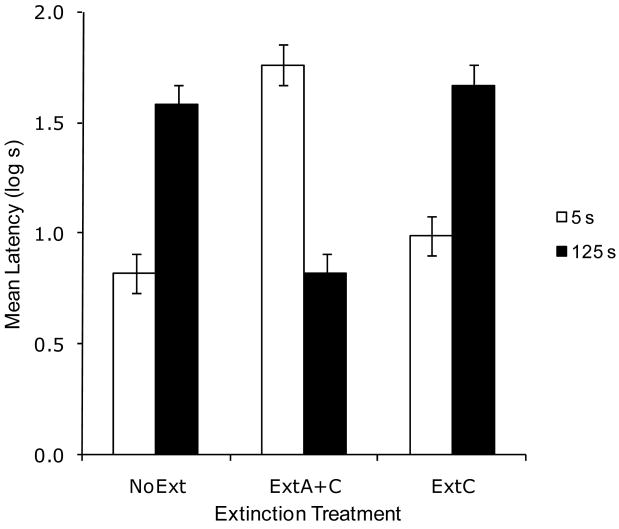

Due to an equipment malfunction, the data of one subject (Group ExtC 125) were lost. Greater conditioned suppression was observed in Group NoExt 125 than in Group NoExt 5, demonstrating a reversal of the overshadowing effect with long CS durations (see Figure 4). After extinction of the overshadowing stimulus and the context (ExtA+C condition), this relationship was reversed. That is, we observed retrospective revaluation with 5 s long cues, and mediated extinction with 125 s long cues, so we identified one variable that determines whether cue competition is observed or not, and this in turn determines the outcome of the posttraining extinction treatment. In contrast, extinction of the context alone had no effect on suppression to X relative to the NoExt condition, regardless of the duration of the CS. These conclusions are supported by the following analyses.

Figure 4.

Results of Experiment 4. Mean log latencies to complete the first five cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the target cue (X). All subjects were trained with the AX compound. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text for details.

A 2 × 3 ANOVA with CS duration (5 vs. 125 s) and extinction (NoExt vs. ExtA+C vs. ExtC) as main factors conducted on pre-CS log latencies did not yield any main effects or interactions, all ps > .50. This means there were no appreciable differences among groups in fear evoked by the testing context. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the log-transformed latencies to resume drinking in the presence of the target CS. This analysis revealed a main effect of CS duration, F(1, 65) = 5.25, MSE = .09, and an interaction between the two factors, F(2, 65) = 61.46, MSE = .09, Cohen's f = 1.31.

Planned comparisons using the overall error term of the latter ANOVA were conducted to identify the source of the interaction. A comparison between the groups in the NoExt condition revealed more responding to the target CS in Group NoExt 125, F(1, 65) = 38.46. This replicates the effects observed in the prior experiments. A comparison between Groups NoExt 5 and ExtA+C 5 detected the recovery from overshadowing effect (i.e., retrospective revaluation), F(1, 65) = 59.85. A comparison between Groups NoExt 125 and ExtA+C 125 detected decreased suppression to the target stimulus due to posttraining extinction of A and the context, F(1, 65) = 38.51. That is, as opposed to the outcome of posttraining extinction seen with short cues (i.e., retrospective revaluation), with long cues we see the opposite outcome, which is a decrease in behavioral control by the target (i.e., mediated extinction). Additionally, a comparison between Groups NoExt 125 and ExtC 125 failed to find a significant effect of posttraining extinction of the context, F(1, 65) = 0.41, p = .52.

In this experiment, we observed that the combination of long CS duration with an overshadowing treatment results in neither detrimental effect being exhibited at test, thus replicating prior experiments in the series. Importantly, conjoint extinction of the overshadowing cue and the context had opposite effects on responding to the target (X) depending on the duration of the cues. When cues were of short duration, extinction of the overshadowing cue resulted in recovery from overshadowing (i.e., retrospective revaluation), as has previously been observed (e.g., Matzel et al., 1985). However, when the cues were of long duration (125 s), not only we did not see an overshadowing effect in the NoExt condition, but we also saw a decrease in responding to the target (X) after extinction of the overshadowing cue and the context (i.e., mediated extinction; e.g., Holland, 1990). Posttraining extinction of the training context alone had no appreciable effect on responding to the target, regardless of the duration of the cues. Obviously one could argue that our treatment was not adequate to induce appreciable context extinction, but we have used these parameters in the past with some success (e.g., Witnauer & Miller, 2007). We discuss the implications of these data in the General Discussion. Lastly, the fact that extinction of the context alone had no effect on responding to X strongly suggests that the observed decrease in responding to X observed when A and the context were conjointly extinguished was due to extinction of A (i.e., mediated extinction) and not of the context.

General Discussion

The main objective of the present series of experiments was to identify a source of the discrepant findings obtained when the more salient cue is extinguished after overshadowing training. We addressed this problem by first examining the interaction of the overshadowing treatment and long CS duration with the intent of illuminating sources of previous discrepant reports concerning posttraining extinction of an overshadowing cue. Prior reports in the literature have often reported increases in responding to the overshadowed target after extinguishing the overshadowing cue (retrospective revaluation; e.g., Kaufman & Bolles, 1981; Matzel et al., 1985; Matzel et al., 1987), but some studies reported the opposite (mediated extinction; e.g., Schachtman et al., 1992; Shevill & Hall, 2004; Exp 1c), and other studies have found no effect (Holland, 1999; Revusky, Parker, & Coombes, 1977). Experiment 1 found that, with elemental training, conditioned suppression to the target stimulus decreased as the duration of the CS increased, and that, with compound cue training, the opposite pattern of responding was observed. That is, conditioned suppression to the target stimulus increased as the duration of the CS increased. Experiment 2 sought to document both retrospective revaluation (Group ExtA+C 5) and mediated extinction (Group ExtA+C 125) effects after overshadowing training. Seemingly, acquired biological significance interfered with the ability to observe mediated extinction, but a significant retrospective revaluation effect was found after training with 5-s long cues and extinguishing the overshadowing stimulus. To circumvent the CS being biologically significant during extinction treatment, we turned to a sensory preconditioning preparation. Experiment 3 replicated and extended the generality of the findings of Experiment 1 using a sensory preconditioning preparation. This replication assured us that our parameters were appropriate to produce both overshadowing and the CS-duration effect, as well as their counteraction, within a sensory preconditioning preparation, thereby allowing us to proceed to Experiment 4. Experiment 4 documented both retrospective revaluation (Group ExtA+C 5) and mediated extinction (Group ExtA+C 125) within a single experiment using a sensory preconditioning preparation. With short CSs retrospective revaluation was observed (Group ExtA+C 5 relative to Group NoExt5), whereas with long CSs mediated extinction occurred (Group ExtA+C 125 relative to Group NoExt 125). This suggests that the strength of the within-compound associations (assuming a monotonic relationship between the amount of exposure of the two cues and the strength of the within-compound association) between punctate cues is one critical factor in determining whether cue competition will be observed. Moreover, under circumstances that result in robust cue competition (i.e., with short cues), retrospective revaluation was observed after posttraining extinction of the overshadowing CS and the context. In contrast, with longer CSs, cue competition was not observed and mediated extinction was observed after extinction of A (and the context, although the context alone did not exert any significant effect).

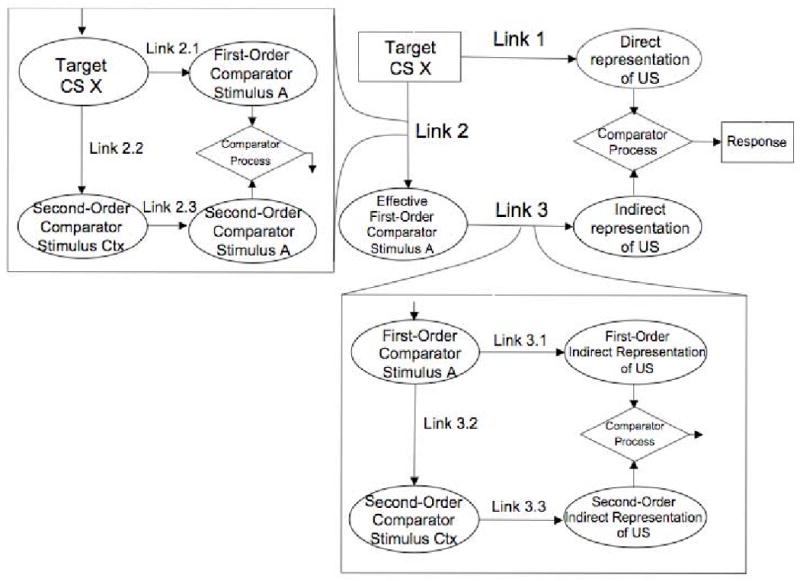

As we mentioned in the introduction, the experiments in this series were inspired by predictions made by the ECH (Denniston et al., 2001) and prior work by Urushihara et al. (2004). The ECH assumes that associations are formed among all stimuli (including outcomes) that are present during training. There are three primary associations (see Figure 5): the conventional target stimulus – outcome association (Link 1), the target stimulus – comparator stimulus association (Link 2), and the comparator stimulus – outcome association (Link 3). A comparator stimulus is any stimulus present during training other than the target cue or outcome. At test, a comparator process determines the level of conditioned responding that will be observed. Conditioned responding increases with the strength of US representation directly activated by the target-US association (Link 1) and decreases with the US representation indirectly activated by the target-comparator association and the comparator-US association (i.e., the product of Links 2 and 3). Additionally, each link is assumed to have its own comparator process. Importantly, the ECH allows all stimuli present during training to also serve as comparator stimuli for each other and consequently compete for potential to interact with the target.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the ECH with A as the first-order comparator stimulus and context as the second-order comparator stimulus. Ctx = context. Rectangles indicate test stimulus and response; ovals indicate mental representations; diamonds indicate comparator mechanism.

The following elaborates upon how the predictions were generated for Experiments 1 and 3: The ECH assumes that long cues have a stronger association with the context which consequently becomes a comparator stimulus for the target after elemental training as well as for the overshadowing stimulus after compound conditioning. Consequently, after compound training with long CSs the target has two comparators, the overshadowing cue and the training context, and these are also comparators for each other. At test, these two comparator stimuli should compete with each other in their roles as comparator stimuli; thus, the ECH anticipates no decrement in behavioral control. This effect is known as a counteraction effect (see Wheeler & Miller, 2008, for a discussion of the boundaries for observing counteractions). Specifically, the context should come to serve as a comparator stimulus for the overshadowing stimulus. This should decrease the effectiveness of the overshadowing stimulus in serving as a comparator stimulus for the target. Similarly, the overshadowing stimulus should come to serve as a comparator stimulus for the context. This in turn should decrease the effectiveness of the context in serving as a comparator stimulus for the target. Consequently, both the overshadowing stimulus and the context come to serve as both the first-order and second-order comparator stimuli for the target. Second-order stimuli modulate the efficacy of first-order stimuli, which in turn modulate responding to the target cue. It is this mechanism that allows the ECH to predict both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction after posttraining extinction. In the case of short duration CSs, compound cues should result in simple overshadowing (provided the trials are widely spaced so that the context does not become a second effective comparator stimulus). In contrast, with long duration compound CSs, the context and the overshadowing cue are predicted to down-modulate each other in the same way that a single, strong comparator down modulates responding to a target cue. The context and the overshadowing cue will then effectively cancel each other so that they do not compete with retrieval of the target CS-US association at the time of testing. Thus, the ECH predicts that treatments such as CS-duration and overshadowing should counteract each other.

The following elaborates upon how predictions were made for Experiments 2 and 4: The ECH suggests that posttraining extinction of either of the target's comparator stimuli (in this case the context and the overshadowing stimulus) should result in retrospective revaluation when cue competition is observed after training (i.e., with 5s CSs) and mediated extinction when cue competition is not observed after training (i.e., with 125 s CSs). Specifically, with short cues, extinction of the overshadowing stimulus should result in a recovery from overshadowing (e.g., Kaufmann & Bolles, 1981; Matzel et al., 1985; i.e., retrospective revaluation). Extinguishing the overshadowing stimulus in a group trained with a compound cue of long duration necessitated long exposure to the context (in order to accommodate the long duration of the stimuli), which one might expect would extinguish both the overshadowing cue and the context, thereby leaving the target stimulus with no effective comparator stimuli and thus strong behavioral control. With short cues, extinction of the context should have little if any effect upon overshadowing because there should not have been a strong target-context association. But extinguishing the training context in a group that received a compound cue of long duration should release the overshadowing stimulus to become the only effective first-order comparator stimulus, thus resulting in mediated extinction (i.e., a decrease in behavioral control by the target).

The results of our experiments with long-duration CSs may seem to contradict earlier reports of cue competition effects with CSs of long duration (e.g., Mackintosh, 1976); it is important to note, however, that the ECH prediction relies on the associative status of the context.In our 125 s conditions we administered four reinforced trials in a 20-min long session, whereas Mackintosh administered two reinforced trials in a 60-min long session. If we use a rough measure of the relationship between CS exposure (T) and context exposure (C; Gibbon & Balsam, 1981) our C/T was 2.4 and Mackintosh's was 15. This likely accounts for the discrepant findings. In terms of the ECH, with a small C/T there is little exposure to the context alone. Consequently the context competes with the target cue for behavioral control when the target is trained alone. However, with a small C/T in the instance of overshadowing treatment being conducted with CSs of a long duration, the overshadowing cue and the context compete with the target for behavioral control (this is the mechanism that generates so called counteraction effects). On the other hand, with a large C/T (e.g., Mackintosh, 1976), the ECH would not predict that the context would become a viable comparator due to the great amount of exposure to the context alone.

Our findings may also seem inconsistent with previous reports that the duration of the overshadowing CS does not influence the degree of overshadowing regardless of whether the overshadowing CS is shorter, longer, or the same duration as the target CS (e.g., Jennings, Bonardi, & Kirkpatrick, 2007). However, it should be noted that Jennings et al. used an appetitive preparation with a US that was far less temporally localized. Moreover, their design was different from ours in that they varied the overshadowing stimulus duration, but not the overshadowed stimulus. These differences may well account for the divergent results.

The ordinal predictions made by the ECH closely match the actual data for all groups in Experiments 1 and 3. Most of the groups in Experiments 2 and 4 also conformed to the predictions of the ECH. However, the behavior of Group ExtC 125 in Experiment 2 is better accounted for by the principle of biological significance. The performances of Groups ExtA+C 125 and ExtC 125 in Experiment 4 are also contrary to expectations based on the ECH, but in these cases the principle of biological significance fails to provide an alternative explanation because we conducted our procedure embedded in a sensory preconditioning preparation. This failure of context extinction to influence responding to the target after compound conditioning with long cues may be due to configuring as a result of extended co-presentation of the two cues (Kehoe & Graham, 1988). That is, the long CS duration may have resulted in a configured cue that was perceptually different from the sum of the two elemental cues. Moreover, one might expect this configured cue to have a higher associability than either A or X alone. High responding to X would then reflect generalization from the configured cue. In a similar vein, the ineffectiveness of context extinction may have been due to a strong within-compound association between the two cues that is relatively independent of the associative status of the context (Westbrook, Homewood, Horn, & Clark, 1983). That is, the long duration of the CS compound and simultaneity of their presentations may have fostered a strong association between the two cues but not encouraged the formation of associations with the context (Rescorla, 1981). Whatever the mechanism underlying the decrease in suppression to X in Group ExtA+C 125 and lack of decrease in suppression in Group ExtC 125 in Experiment 4, the data are contrary to predictions of the ECH. Apparently the linearity of retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction with respect to the X-A and X-context associations breaks down as these within-compound associations become very strong.

Recent data published by Liljeholm and Balleine (2008) also suggest that retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction are influenced by configural vs. elemental processing. With humans they found mediated extinction when learning conditions favored configural processing and retrospective revaluation when learning conditions favored elemental processing. This view is concordant with our previous statement that the long co-presentation of the cues may have resulted in some configural learning of the compound.

As mentioned in the introduction, there have been a number of discrepant findings regarding the effect of posttraining extinction of the companion (nontarget) cue after reinforced compound cue training. The source of these discrepant findings has been unclear (but see Dwyer, 1999) and these inconsistencies have lead to theoretical disagreements. There are theories that anticipate mediated extinction (e.g., Holland, 1990), retrospective revaluation (e.g., Dickinson & Burke, 1996; Miller & Matzel, 1988; Van Hamme & Wasserman, 1994), no change (e.g., Rescorla & Wagner, 1972, Wagner, 1981), and all three as a function of parameters (Denniston et al., 2001). In the current experiments, we observed both mediated extinction and retrospective revaluation (Exp. 4), and we were able to isolate one critical determinant of these two opposing outcomes, that being the strength of the within-compound association between the target and its companion stimulus but not unambiguously so, because varying the CS duration likely also altered associations with the context.

Perhaps another reason for these discrepant findings lies on the use of procedures that result in the target cue acquiring different degrees of biological significance during compound training. Prior studies from our laboratory have consistently demonstrated that cues that have inherent or acquired significance are relatively immune to indirect manipulations of their companion cue that might be expected to decrease behavioral control (Denniston et al., 1996; Miller & Matute, 1998; Oberling et al., 2000). The behavior of Group ExtC 125 in Experiment 2 was consistent with this view. In that experiment, we observed an increase in behavioral control by the 5-s overshadowed (target) cue after extinction of the overshadowing cue, whereas no change was observed when the cues were 125 s in duration and a decrease in behavioral control was expected according to the ECH. Experiment 4, which was embedded within a sensory preconditioning preparation, circumvented the limits of acquired biological significance and allowed for the observation of both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction.

Yet another variable, perhaps related to the above-mentioned biological significance, which could influence the observed opposing outcomes, is the motivational system engaged in the different preparations used to investigate compound cue training and subsequent posttraining manipulations (Dwyer, 1999). In Pavlovian fear conditioning in laboratory settings, subjects usually experience auditory stimuli that are presented contiguously with a brief footshock. Under these circumstances learning proceeds rapidly and achieves asymptotic levels with few trials. In appetitive conditioning, the interval between cue termination and US consumption is not under full control of the researcher; rather it is dependent on the subject's behavior. Moreover, the loci and timing of the reinforcing properties of the US are not as discrete as they are in fear conditioning. Perhaps different Pavlovian preparations result in different levels of acquired biological significance due to differences in CS-US contiguity and the discreteness of the unconditioned effects of the reinforcer. This in turn could determine the effect of posttraining manipulations, just as first-order conditioning and sensory preconditioning procedures here resulted in different results in Experiments 2 and 4. Although we do not know if the results observed here would be seen with an appetitive preparation, the present set of studies conducted in a fear conditioning preparation identified one variable (CS duration) that determines which of these two outcomes is to be observed. Importantly, we were able to obtain both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction in a single experiment. Notably, Liljeholm and Balleine (2006) identified stimulus salience as a factor that influences the observation of retrospective revaluation after posttraining extinction of a stimulus trained in compound. After overshadowing training either the more or less salient stimulus was extinguished and then the subjects were tested on the other stimulus. When the more salient stimulus was extinguished, they observed retrospective revaluation, but when the less salient stimulus was extinguished they saw no effect. Importantly, Liljeholm and Balleine's preparation was appetitively motivated, which suggests that under some conditions retrospective revaluation effects are readily observed in appetitive preparations.

In summary, the present series of experiments documented and extended Urushihara et al.'s (2004) findings of counteraction between overshadowing and CS duration. Specifically, we saw overshadowing with short CSs and no overshadowing with long CSs. More important, the duration of the compound determined the outcome of posttraining extinction of the overshadowing cue. With short cues we saw retrospective revaluation and with long cues we saw mediated extinction.

Acknowledgments

NIMH Grant 33881 provided support for this research. We thank Eric Curtis, Sean Gannon, Ryan Green, Jeremie Jozefowiez, Mario Laborda, Bridget McConnell, Mikael Molet, Lisa Ng, and James Witnauer for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

References

- Brogden WJ. Sensory pre-conditioning. Journal of Experimental of Psychology. 1939;25:323–332. doi: 10.1037/h0058465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JC, Westbrook RF, Irwin J. Potentiation instead of overshadowing in the pigeon. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1979;25:18–29. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(79)90705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Miller RR, Matute H. Biological significance as a determinant of cue competition. Psychological Science. 1996;7:325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Savastano HI, Miller RR. The extended comparator hypothesis: Learning by contiguity, responding by relative strength. In: Mowrer RR, Klein SB, editors. Handbook of Contemporary Learning Theories. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 65–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, Burke J. Within-compound associations mediate the retrospective revaluation of causality judgments. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49B:60–80. doi: 10.1080/713932614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer DM. Retrospective revaluation or mediated conditioning? The effect of different reinforcers. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1999;52B:289–306. doi: 10.1080/027249999393013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Balsam P. Spreading association in time. In: Locurto CM, Terrace HS, Gibbon J, editors. Autoshaping and conditioning theory. New York: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 219–253. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Event representation in Pavlovian conditioning: Image and action. Cognition. 1990;37:105–131. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90020-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Overshadowing and blocking as acquisition deficits: No recovery after extinction of overshadowing or blocking cues. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1999;52B:307–333. doi: 10.1080/027249999393022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings DJ, Bonardi C, Kirkpatrick K. Overshadowing and stimulus duration. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2007;33:464–475. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.33.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MA, Bolles RC. A nonassociative aspect of overshadowing. Bulletin of Psychonomic Society. 1981;18:318–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe JE, Graham P. Summation and Configuration: Stimulus compounding and negative patterning in the rabbit. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1988;14:320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Laborda M, Witnauer JE, Miller RR. Contrasting AAB and ABC renewal: The role of context associations. 2008 doi: 10.3758/s13420-010-0007-1. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeholm M, Balleine BW. Stimulus salience and retrospective revaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:481–487. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeholm M, Balleine BW. Mediated conditioning versus retrospective revaluation in humans: The influence of physical and functional similarity of cues. [November 17, 2008];Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008 doi: 10.1080/17470210802008805. http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/17470210802008805. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lipatova O, Wheeler DS, Vadillo MA, Miller RR. Recency-to-primacy shift in cue competition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:396–406. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh NJ. A theory of attention: Variations in the associability of stimuli with reinforcements. Psychological Review. 1975;82:276–298. [Google Scholar]